Abstract

Using a variety of data sets from two countries, we examine possible explanations for the relationship between education and health behaviors, known as the education gradient. We show that income, health insurance, and family background can account for about 30 percent of the gradient. Knowledge and measures of cognitive ability explain an additional 30 percent. Social networks account for another 10 percent. Our proxies for discounting, risk aversion, or the value of future do not account for any of the education gradient, and neither do personality factors such as a sense of control of oneself or over one’s life.

In 1990, a 25 year-old male college graduate could expect to live another 54 years. A high school dropout of the same age could expect to live 8 years fewer (Richards and Barry, 1998). This enormous difference in life expectancy by education is true for every demographic group, is persistent – if not increasing – over time (Kitagawa and Hauser, 1973; Elo and Preston, 1996; Meara, Richards, and Cutler, 2008), and is present in other countries (Marmot, Shipley, and Rose, 1984 (the U.K.); Mustard, et al. 1997 (Canada); Kunst and Mackenbach, 1994 (northern European countries)).1

A major reason for these differences in health outcomes is differences in health behaviors. 2 In the United States, smoking rates for the better educated are one-third the rate for the less educated. Obesity rates are half as high among the better educated (with a particularly pronounced gradient among women), as is heavy drinking. Mokdad et al. (2004) estimate that nearly half of all deaths in the United States are attributable to behavioral factors, most importantly smoking, excessive weight, and heavy alcohol intake. Any theory of health differences by education thus needs to explain differences in health behaviors by education. We search for explanations in this paper.3

In standard economic models, people choose different consumption bundles because they face different constraints (for example, income or prices differ), because they have different beliefs about the impact of their actions, or because they have different tastes. We start by showing, as others have as well, that income and price differences do not account for all of these behavioral differences. We estimate that access to material resources, such as gyms and smoking cessation methods, can account for at most 30 percent of the education gradient in health behaviors. Price differences work the other way. Many unhealthy behaviors are costly (smoking, drinking, and overeating), and evidence suggests that the less educated are more responsive to price than the better educated. As a result, we consider primarily differences in information and in tastes.

Some of the differences by education are indeed due to differences in specific factual knowledge — we estimate that knowledge of the harms of smoking and drinking accounts for about 10 percent of the education gradient in those behaviors. However, more important than specific knowledge is how one thinks. Our most striking finding, shown using US and UK data, is that a good deal of the education effect – about 20 percent – is associated with general cognitive ability. Furthermore this seems to be driven by the fact that education raises cognition which in turn improves behavior.

A lengthy literature suggests that education affects health because both are determined by individual taste differences, specifically in discounting, risk aversion, and the value of the future—which also affect health behaviors and thus health. Victor Fuchs (1982) was the first to test the theory empirically, finding limited support for it. We know that taste differences in childhood cannot explain all of the effect of schooling, since a number of studies show that exogenous variation in education influences health. For example, Lleras-Muney (2005) shows that adults affected by compulsory schooling laws when they were children are healthier than adults who left school earlier. Currie and Moretti (2003) show that women living in counties where college is more readily available have healthier babies than women living in other counties. However, education can increase the value of the future simply by raising earnings and can also change tastes.

Nevertheless, using a number of different measures of taste and health behaviors, we are unable to find a large impact of differences in discounting, value of the future, or risk aversion on the education gradient in health behaviors. Nor do we find much role for theories that stress the difficulty of translating intentions into actions, for example, that depression or lack of self control inhibits appropriate action (Salovey, Rothman, and Rodin, 1998). Such theories are uniformly unsupported in our data, with one exception: about 10 percent of the education gradient in health behaviors is a result of greater social and emotional support.

All told, we account for about two-thirds of the education gradient with information on material resources, cognition, and social interactions. However, it is worth noting that our results have several limitations. First, we lack the ability to make causal claims, especially because it is difficult to estimate models where multiple mechanisms are at play. Second, we recognize that in many cases the mechanisms we are testing require the use of proxies which can be very noisy, causing us to dismiss potentially important theories. Nevertheless we view this paper as an important systematic exploration of possible mechanisms, and as suggesting directions for future research.

The paper is structured as follows. We first discuss the data and empirical methods. The next section presents basic facts on the relation between education and health. The next two sections discuss the role of income and prices in mediating the education-behavior link. The fourth section considers other theories about why education and health might be related: the cognition theory; the future orientation theory; and the personality theory. These theories are then tested in the next three sections. We then turn to data from the U.K. The final section concludes.

I. Data and Methods

In the course of our research, we use a number of different data sets. These include the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS), the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), the Survey on Smoking (SOS), and the National Childhood Development Study (NCDS) in the U.K. We use many data sets because no single source of data has information allowing us to test all the relevant theories. For the US we have restricted our attention to the whites only because our earlier work showed larger education gradients among them (Cutler and Lleras-Muney 2008b) but the results presented here are not particularly sensitive to that choice. A lengthy data appendix discusses the surveys in more detail.

In all data sets we restrict the samples to individuals ages 25 and above (so education has been mostly completed)—but place no upper limit on age. The health behaviors we look at are self-reported. This is a limitation of our study, but we were unable to find data containing measured (rather than self reported) behaviors to test our theories.4 To the extent that biases in self reporting vary across behaviors, our use of multiple health behaviors mitigates this bias. Nevertheless it is worth noting that not much is known about whether biases in reporting vary systematically by education.

To document the effect of education on health behaviors, we estimate the following regression:

| (1) |

Where Hi is a health behavior of individual i, Education is measured as years of schooling in the US, and as a dummy for whether the individual passed any A level examinations in the UK.5 The basic regression controls for basic demographic characteristics (gender, age dummies and ethnicity) and all available parental background measures (which vary depending on the data we use). Ideally in this basic specification we would like to control for parent characteristics and all other variables that determine education but cannot be affected by it, such as genetic and health endowments at birth— we control for the variables that best seem to fit this criterion in each data set.6 The education gradient is given by β1, the coefficient on education, and measures the effect of schooling on behavior, which could be thought of as causal if our baseline controls were exhaustive. We discuss below whether the best specification of education is linear or non-linear.

In testing a particular theory we then re-estimate equation (1) adding a set of explanatory variables Z:

| (2) |

We then report, for each health measure, the percent decline in the coefficient of education from adding each set of variables, 1 - α1/β1.

Many of our health measures are binary. To allow for comparability across outcomes, we estimate all models using linear probability, but our results are not very different if we instead use a non-linear model. Thus, the coefficients are the percentage point change in the relevant outcome. Since we have many outcomes, it is helpful to summarize them in a single number. We use three methods to form a summary. First we compute the average reduction of the gradient across outcomes for those outcomes with a statistically significant gradient in the baseline specification. Of course, not all behaviors contribute equally to health outcomes. Our second summary measure weights the different behaviors by their impact on mortality. The regression model, using the 1971–75 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Epidemiological Follow-up Study, is described in the Appendix. For comparability reasons, the behaviors are restricted to smoking, drinking, and obesity. The summary measure is the predicted change in 10 year mortality associated with each additional year of education.7 Finally, we report the average effect of education across outcomes using the methodology described in Kling, Liebman, and Katz (2007), which weights outcomes equally after standardizing them.8

II. Education and Health Behaviors: The Basic Facts

We start by presenting some basic facts relating education and health behaviors, before discussing theories linking the two. Health behaviors are asked about in a number of surveys. Probably the most complete is the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). In order to examine as many behaviors as possible, we use data from a number of NHIS years, 1990, 1991, 1994 and 2000.9 We group health behaviors into eight groups: smoking, diet/exercise, alcohol use, illegal drugs, automobile safety, household safety, preventive care, and care for people with chronic diseases (diabetes or hypertension). Within each group, there are multiple measures of health behaviors. Because the NHIS surveys are large, our sample sizes are up to approximately 23,000.

Table 1 shows the health behaviors we analyze and the mean rates in the adult population. We do not remark upon each variable, but rather discuss a few in some depth. Current cigarette smoking is a central measure of poor health. Mokdad et al. (2004) estimate that cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable deaths in the country (accounting for 18 percent of all deaths). The first row shows that twenty-three percent of white adults in 2000 smoked cigarettes. The next columns relate cigarette smoking to years of education, entered linearly. We control for single year of age dummies, a dummy for females, and a dummy for Hispanic.

Table 1.

Health Behaviors for Whites over 25 National Health Interview Survey

| Demographic Controls |

Adding Income |

Adding Income and other Economic |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Mean | N | Year | Years of Education (β) |

std error | Years of Education (β) |

std error | Reduction in Education Coefficient |

Years of Education (β) |

std error | Reduction in Education Coefficient |

| Smoking | |||||||||||

| Current smoker | 23% | 22141 | 2000 | −0.030 | (0.001) ** | −0.022 | (0.001) ** | 26% | −0.020 | (0.001) ** | 33% |

| Former smoker | 26% | 22270 | 2000 | 0.004 | (0.001) ** | 0.002 | (0.001) | 58% | 0.001 | (0.001) | 79% |

| Ever smoked | 49% | 22156 | 2000 | −0.026 | (0.001) ** | −0.021 | (0.001) ** | 20% | −0.019 | (0.001) ** | 25% |

| Number cigs a day (smokers) | 17.7 | 4910 | 2000 | −0.697 | (0.068) ** | −0.561 | (0.071) ** | 19% | −0.444 | (0.073) ** | 36% |

| Made serious attempt to quit ° | 64% | 7603 | 1990 | 0.013 | (0.002) ** | 0.011 | (0.002) ** | 12% | 0.011 | (0.002) ** | 16% |

| Diet/Exercise | |||||||||||

| Body mass index (BMI) | 26.7 | 21401 | 2000 | −0.190 | (0.014) ** | −0.159 | (0.015) ** | 16% | −0.139 | (0.016) ** | 27% |

| Underweight (bmi<=18.5) | 2% | 21401 | 2000 | −0.0005 | (0.0004) | −0.0001 | (0.0004) | 85% | 0.0000 | (0.0004) | 98% |

| Overweight (bmi>=25) | 59% | 21401 | 2000 | −0.014 | (0.001) ** | −0.014 | (0.001) ** | 0% | −0.013 | (0.001) ** | 12% |

| Obese (bmi>=30) | 22% | 21401 | 2000 | −0.014 | (0.001) ** | −0.011 | (0.001) ** | 18% | −0.010 | (0.001) ** | 28% |

| How often eat fruit or veggies per day | 1.9 | 22285 | 2000 | 0.079 | (0.004) ** | 0.067 | (0.004) ** | 16% | 0.067 | (0.004) ** | 15% |

| Ever do vigorous activity | 39% | 22003 | 2000 | 0.039 | (0.001) ** | 0.032 | (0.001) ** | 18% | 0.028 | (0.001) ** | 28% |

| Ever do moderate activity | 53% | 21768 | 2000 | 0.037 | (0.001) ** | 0.030 | (0.001) ** | 17% | 0.029 | (0.001) ** | 21% |

| Alcohol | |||||||||||

| Had 12+ drinks in entire life | 80% | 22054 | 2000 | 0.021 | (0.001) ** | 0.017 | (0.001) ** | 19% | 0.014 | (0.001) ** | 33% |

| Drink at least once per month | 47% | 21803 | 2000 | 0.033 | (0.001) ** | 0.025 | (0.001) ** | 24% | 0.020 | (0.001) ** | 41% |

| Number of days had 5+ drinks past year- drinkers | 10.8 | 13458 | 2000 | −2.047 | (0.157) ** | −1.711 | (0.167) ** | 16% | −1.754 | (0.170) ** | 14% |

| Number of days had 5+ drinks past year- all | 6.8 | 21663 | 2000 | −0.848 | (0.092) ** | −0.703 | (0.098) ** | 17% | −0.763 | (0.100) ** | 10% |

| Average # drinks on days drank | 2.3 | 13600 | 2000 | −0.162 | (0.012) ** | −0.162 | (0.012) ** | 0% | −0.144 | (0.012) ** | 11% |

| Heavy drinker (average number of drinks>=5) | 8% | 13600 | 2000 | −0.018 | (0.001) ** | −0.015 | (0.001) ** | 12% | −0.015 | (0.001) ** | 13% |

| Drove drunk past year ° | 11% | 17121 | 1990 | −0.003 | (0.001) ** | −0.002 | (0.001) ** | 27% | −0.005 | (0.001) ** | −38% |

| Number of times drove drunk past year ° | 93% | 17121 | 1990 | −0.140 | (0.036) ** | −0.103 | (0.038) ** | 27% | −0.119 | (0.040) ** | 15% |

| Illegal Drugs | |||||||||||

| Ever used marijuana ° | 48% | 13413 | 1991 | 0.015 | (0.002) ** | 0.014 | (0.002) ** | 9% | 0.009 | (0.002) ** | 41% |

| Used marijuana, past 12 months ° | 8% | 13413 | 1991 | −0.001 | (0.001) | 0.000 | (0.001) | 139% | −0.002 | (0.001) ** | −100% |

| Ever used cocaine ° | 16% | 13174 | 1991 | 0.005 | (0.001) ** | 0.005 | (0.001) ** | −14% | 0.000 | (0.001) | 94% |

| Used cocaine, past 12 months ° | 2% | 13174 | 1991 | 0.000 | (0.000) | 0.000 | (0.001) | --- | −0.001 | (0.001) | --- |

| Ever used any other illegal drug ° | 22% | 13370 | 1991 | 0.003 | (0.014) ** | 0.006 | (0.002) ** | −80% | 0.001 | (0.002) ** | 79% |

| Used other illegal drug, past 12 months ° | 5% | 13176 | 1991 | −0.002 | (0.001) ** | 0.000 | (0.001) | 87% | −0.002 | (0.001) ** | 20% |

| Automobile Safety | |||||||||||

| Always wear seat belt ° | 69% | 29993 | 1990 | 0.033 | (0.001) ** | 0.027 | (0.001) ** | 19% | 0.026 | (0.001) ** | 23% |

| Never wear seat belt ° | 9% | 29993 | 1990 | −0.014 | (0.001) ** | −0.011 | (0.001) ** | 20% | −0.011 | (0.001) ** | 22% |

| Household Safety | |||||||||||

| Know poison control number ° | 65% | 6838 | 1990 | 0.031 | (0.002) ** | 0.026 | (0.002) ** | 18% | 0.027 | (0.002) ** | 15% |

| 1 + working smoke detectors ° | 80% | 29021 | 1990 | 0.019 | (0.001) ** | 0.012 | (0.001) ** | 36% | 0.012 | (0.001) ** | 38% |

| House tested for radon ° | 4% | 28440 | 1990 | 0.007 | (0.000) ** | 0.005 | (0.000) ** | 29% | 0.005 | (0.000) ** | 25% |

| Home paint ever tested for lead ° | 4% | 9600 | 1991 | 0.000 | (0.001) | 0.001 | (0.001) | --- | −0.001 | (0.001) | --- |

| At least 1 firearm in household | 42% | 14207 | 1994 | −0.011 | (0.002) ** | −0.019 | (0.002) ** | −73% | −0.012 | (0.002) ** | −9% |

| All firearms in household are locked (has firearms) | 36% | 5268 | 1994 | −0.005 | (0.003) ** | −0.008 | (0.003) ** | −60% | −0.007 | (0.003) ** | −40% |

| All firearms in household are unloaded (has firearms) | 81% | 5262 | 1994 | 0.006 | (0.002) ** | 0.003 | (0.001) ** | 50% | 0.004 | (0.002) ** | 33% |

| Preventive Care-recommended population | |||||||||||

| Ever had mammogram-age 40+ | 87% | 8169 | 2000 | 0.017 | (0.001) ** | 0.013 | (0.002) ** | 27% | 0.010 | (0.002) ** | 40% |

| Had mamogram w/in past 2 yrs | 56% | 8100 | 2000 | 0.026 | (0.002) ** | 0.017 | (0.002) ** | 34% | 0.014 | (0.002) ** | 45% |

| Ever had pap smear test | 97% | 11866 | 2000 | 0.009 | (0.001) ** | 0.009 | (0.001) ** | 7% | 0.009 | (0.001) ** | 1% |

| Had pap smear w/in past yr | 62% | 11748 | 2000 | 0.028 | (0.002) ** | 0.019 | (0.002) ** | 32% | 0.015 | (0.002) ** | 46% |

| Ever had colorectal screening-age 40+ | 31% | 14302 | 2000 | 0.021 | (0.001) ** | 0.019 | (0.002) ** | 11% | 0.018 | (0.002) ** | 14% |

| Had colonoscopy w/in past yr | 9% | 14259 | 2000 | 0.007 | (0.001) ** | 0.007 | (0.001) ** | 11% | 0.006 | (0.001) ** | 17% |

| Ever been tested for hiv | 30% | 20853 | 2000 | 0.011 | (0.001) ** | 0.011 | (0.001) ** | 0% | 0.011 | (0.001) ** | 2% |

| Had an std other than hiv/aids, past 5 y | 2% | 11398 | 2000 | 0.000 | (0.001) | 0.001 | (0.001) | --- | 0.000 | (0.001) | --- |

| Had flu shot past 12 mo | 32% | 22047 | 2000 | 0.014 | (0.001) ** | 0.013 | (0.001) ** | 11% | 0.013 | (0.001) ** | 11% |

| Ever had pneumonia vaccination | 18% | 21705 | 2000 | 0.005 | (0.001) ** | 0.006 | (0.001) ** | −30% | 0.006 | (0.001) ** | −25% |

| Ever had hepatitis b vaccine | 19% | 21118 | 2000 | 0.018 | (0.001) ** | 0.017 | (0.001) ** | 4% | 0.017 | (0.001) ** | 8% |

| Received all 3 hepatitis B shots | 15% | 20848 | 2000 | 0.015 | (0.001) ** | 0.014 | (0.001) ** | 6% | 0.014 | (0.001) ** | 7% |

| Among Diabetics | |||||||||||

| Are you now taking insulin | 32% | 1442 | 2000 | −0.002 | (0.004) | −0.003 | (0.004) | −38% | −0.003 | (0.005) | −36% |

| Are you now taking diabetic pills | 66% | 1443 | 2000 | −0.006 | (0.004) | −0.004 | (0.004) | 25% | −0.004 | (0.005) | 40% |

| Blood pressure high at last reading ° | 7% | 28373 | 1990 | −0.005 | (0.001) ** | −0.004 | (0.001) ** | 24% | −0.004 | (0.001) ** | 24% |

| Among hypertensives | |||||||||||

| Still have high bp ° | 47% | 6899 | 1990 | −0.012 | (0.002) ** | −0.010 | (0.002) ** | 19% | −0.009 | (0.002) ** | 25% |

| High bp is cured (vs controlled) ° | 26% | 3537 | 1990 | 0.000 | (0.003) | −0.001 | (0.003) | --- | −0.002 | (0.003) | --- |

| Average Reduction in Education Coefficient | |||||||||||

| Unweighted (outcomes w/significant gradients at baseline) | 12% | 22% | |||||||||

| Mortality weighted | 11% | 24% | 32% | ||||||||

Notes: Sample sizes are constant across columns. Demographic controls include a full set of dummies for age, gender, and Hispanic origin. Economic controls include family income, family size, major activity, region, MSA, marital status, and whether covered by health insurance.

Outcomes marked with ° came from waves of the NHIS that did not collect health insurance data, so health insurance is not included in these regressions. Self reports are from questions of the form "Has a doctor ever told you that you have …?" Unweighted average reduction in education coefficient is calculated for all behaviors where the education effect without controls is statistically significant. NHIS weights are used in all regressions and in calculating means.

(*) indicates statistically significant at the 5% (10%) level.

Each year of education is associated with a 3.0 percentage point lower probability of smoking. Put another way, a college grad is 12 percentage points less likely to smoke than a high school grad. Given that smoking is associated with 6 years shorter life expectancy (Cutler et al., 2000), this difference is immense.

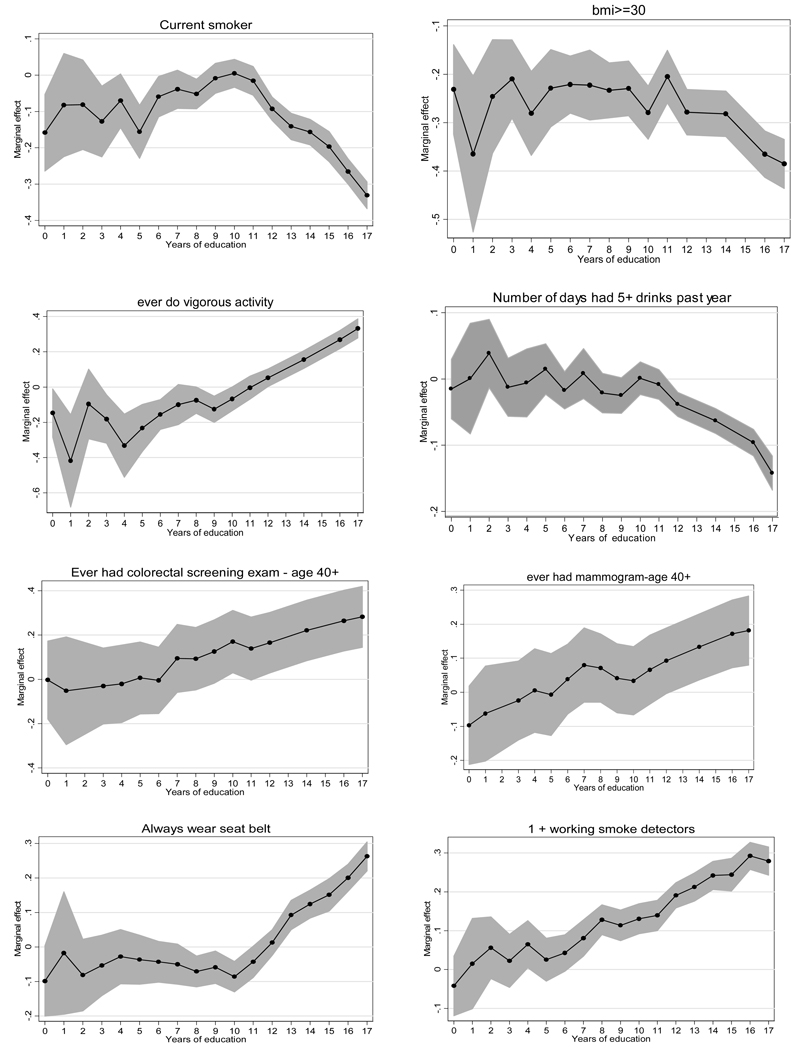

Entering education linearly may not be right. One might imagine that some base level of education is important, and that additional education beyond that level would not reduce smoking. That is not correct, however. The first part of Figure 1 shows the relationship between exact years of education and smoking: the figure reports the marginal effect of an additional year of education for each level of education, estimated using a logit model. If anything, the story is the opposite of the ‘base education’ hypothesis; the impact of education is greater at higher levels of education, rather than lower levels of education (although there are few observations at the lower end of the education distribution and thus these estimates are imprecise). Overall the relationship appears to be linear above 10 years of schooling for all of the outcomes in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Effect of education on various health behaviors, by single year of schooling.

Note: Marginal effects from logit regressions on education, controlling for race and gender. The shaded areas are 95% confidence intervals for each coefficient. Exact years of education are not available in all surveys and were imputed as the middle of the education category. Years of education is top coded as 17.

Next to smoking, obesity is the leading behavioral cause of death. While all measures of excess weight are correlated, we focus particularly on obesity (defined as a Body Mass Index or BMI equal to or greater than 30). Twenty-two percent of the population in 2000 self-reported themselves to be obese.10 This too is negatively related to education; each year of additional schooling reduces the probability of being obese by 1.4 percent (Table 1). The shape by exact year of education is similar to that for smoking (Figure 1). Obesity declines particularly rapidly for people with more than 12 years of education.

Heavy drinking is similarly harmful to health. We focus on the probability that the person is a heavy drinker – defined as having an average of 5 or more drinks when a person drinks. Eight percent of people are heavy drinkers. Each additional year of education lowers this by 1.8 percent. Interestingly the better educated are more likely to drink but less likely to drink heavily.

Self-reported use of illegal drugs is relatively low; only 2 to 8 percent of people report using such drugs in the past year. Recent use of illegal drugs is generally unrelated to education (at least for marijuana and cocaine). But better educated people report they are more likely to have ever tried these drugs. Better educated people seem better at quitting bad habits, or at controlling their consumption. This shows up in cigarette smoking as well, where the gradient in current smoking is somewhat greater than the gradient in ever smoking.

Automobile safety is positively related to education; better educated people wear seat belts much more regularly than less educated people. The mean rate of always wearing a seat belt is 69 percent; each year of education adds 3.3 percent to the rate. The analysis of seat belt use is particularly interesting. Putting on a seat belt is as close to costless as a health behavior comes. Further, knowledge of the harms of non-seat belt use is also very high. But the gradient in health behaviors is still extremely large.

Household safety is similarly related to education. Better educated people keep dangerous objects such as handguns safe and know what to do when something does happen (for example, they know the poison control phone number).

Better educated people engage in more preventive and risk control behavior. Better educated women get mammograms and pap smears more regularly, better educated men and women get colorectal screening and other tests, and better educated people are more likely to get flu shots. Among those with hypertension, the better educated are more likely to have their blood pressure under control. Services involving medical care are the least clear of our education gradients to examine, since access to health care matters for receipt of these services. We thus focus more on the other behaviors. But, these data are worth remarking on because it does not appear that access to medical care is the big driver. Controlling for receipt of health insurance does not diminish these gradients to any large extent (the education coefficient on receipt of a mammogram is reduced by only 18 percent, for example, if we control for insurance in addition to age and ethnicity alone). This is consistent with the Rand Health Insurance Experiment (Newhouse et al., 1993); making medical care free increases use, but even when care is free, there is still significant underuse. Seeing a doctor may be like wearing a seat belt; it is something that better educated people do more regularly.

Table 1 makes clear that education is associated with an enormous range of positive health behaviors, the majority of health behaviors that we explore. The average predicted 10 year mortality rate is 11 percent, shown in the last row of the Table. Relative to this average, our results suggest that every year of education lowers the mortality risk by 0.3 percentage points, or 24 percent, through reduction in risky behaviors (drinking, smoking, and weight).

We have examined the education gradient in health behaviors using other data sets as well. Some of these results are presented later in the paper. In each case, there are large education differences across a variety of health behaviors and for somewhat different samples. Education differences in health behaviors are not specific to the United States. They are apparent in the U.K. as well. As documented later in the paper (Appendix Table 3), we analyze a sample of British men and women at ages 41–42. People who passed the A levels are 15 percent less likely to smoke than those who did not pass. Additionally those that passed A levels are 6 percent less likely to be obese, and are 3 percent less likely to be heavy drinkers.

Appendix Table 3.

Explanations for Health Differences in the NCDS. Summary statistics by Education Level

| Variable | Did not pass A levels |

Passed A levels |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | N | Mean | Min | Max | |

| Cognitive Measures | ||||||

| Age 7 | ||||||

| Math (arithmetic) | 7,128 | 4.78 | 2,973 | 6.39 | 0 | 10 |

| Drawing (Draw-a-man test) | 7,017 | 23.14 | 2,913 | 26.29 | 0 | 53 |

| Age 11 | ||||||

| Reading Comprehension | 6,892 | 14.59 | 2,909 | 20.90 | 0 | 35 |

| Math | 6,892 | 14.28 | 2,907 | 25.21 | 0 | 40 |

| Verbal | 6,893 | 20.46 | 2,908 | 28.91 | 0 | 40 |

| Non-verbal | 6,893 | 19.67 | 2,908 | 26.29 | 0 | 40 |

| Drawing (Copying designs) | 6,881 | 8.23 | 2,901 | 8.83 | 0 | 12 |

| Age 16 | ||||||

| Reading Comprehension | 5,963 | 23.86 | 2,639 | 30.54 | 0 | 35 |

| Math | 5,930 | 10.72 | 2,636 | 19.01 | 0 | 31 |

| Life Satisfaction | ||||||

| Current (0=min; 10=max) | 7,927 | 7.23 | 3,337 | 7.43 | 0 | 10 |

| In ten years (0=min; 10=max) | 7,906 | 8.03 | 3,332 | 8.11 | 0 | 10 |

| Personality scales | ||||||

| efficacy 1 (never get what I want out of life=1) | 7,904 | 0.26 | 3,328 | 0.15 | 0 | 1 |

| efficacy 2 (usually have control over my life=1) | 7,916 | 0.87 | 3,334 | 0.94 | 0 | 1 |

| efficacy 3 (can run my life how I want=1) | 7,916 | 0.94 | 3,331 | 0.96 | 0 | 1 |

| Malaise Index (1=healthy; 24=unhealthy) | 7,920 | 3.86 | 3,336 | 2.96 | 0 | 24 |

| GHQ12 (1=low stress; 12=high stress) | 7,927 | 1.83 | 3,338 | 1.88 | 0 | 12 |

| Socialization | ||||||

| Mother is alive (percent) | 7,692 | 0.76 | 3,280 | 0.82 | 0 | 1 |

| Frequency sees mother (0=every day, 4=never) | 6,169 | 1.67 | 2,756 | 2.08 | 0 | 4 |

| Father is alive (percent) | 7,756 | 0.57 | 3,305 | 0.64 | 0 | 1 |

| Frequency sees father (0=every day, 4=never) | 4,580 | 1.85 | 2,141 | 2.23 | 0 | 4 |

| Frequency eat together as a family (1=daily, 5=never) | 5,090 | 2.18 | 2,197 | 2.12 | 1 | 5 |

| Frequency go out together as a family (1=daily, 5=never) | 5,126 | 2.65 | 2,254 | 2.17 | 1 | 5 |

| Frequency visit relatives as a family (1=daily, 5=never) | 5,177 | 2.11 | 2,274 | 2.14 | 1 | 5 |

| Frequency go on holiday as a family (1=weekly, 5=never) | 5,106 | 3.83 | 2,260 | 3.50 | 1 | 5 |

| Frequency go out alone or with friends (1=weekly, 4=never) | 6,328 | 2.24 | 2,719 | 2.16 | 1 | 4 |

| Frequency attends religious services (1=weekly, 4=never) | 6,900 | 3.54 | 2,580 | 3.04 | 1 | 4 |

III. Education as Command over Resources

An obvious difference between better educated and less educated people is resources. Better educated people earn more than less educated people, and these differences in earnings could affect health. There are two channels for this. First, higher income allows people to purchase goods that improve health, for example health insurance. In addition, higher income increases steady-state consumption, and thus raises the utility of living to an older age. We focus here on the impact of current income as a whole, and consider specifically the value of the future in a later section.

A number of studies suggest that both education and income are each associated with better health. Thus, it is clear that income does not account for all of the education relationship. But for our purposes, the magnitude of the covariance is important. We examine this by adding income to our basic regressions in Table 1. The NHIS asks about income in 9 categories (13 in 2000). We include dummy variables for each income bracket. There are endogeneity issues with income. Current income might be low because a person is sick, rather than the reverse—although the endogeneity problem is less clear for behaviors than for health. Nevertheless, we can interpret these variables as a sensitivity test for the potential role of income as a mediating factor.

The second columns in Table 1 report regressions including family income. Adding income accounts for some of the education effect. For example, the coefficient on years of education in the current smoking equation falls by 26 percent. The coefficient on body mass index falls by 16 percent (roughly the same as the fall in the coefficients on overweight and obese), and the coefficient on heavy drinking falls by 12 percent. The average decline (for outcomes with a significant gradient at baseline) is 12 percent. The mortality-weighted average is a decline of 24 percent. It is worth noting that our income measure includes both permanent and transitory income and further is measured with error. Thus, the reduction in education coefficients we observe might be too small.

The NHIS contains a number of other measures of economic status beyond current income, including major activity (whether individual is working, at home, in school, etc), whether the person is covered by health insurance,11 geographic measures (region and urban location), family size, and marital status. These variables are likely to determine permanent income and in principle can be affected by educational attainment.

As with income, each of these variables may be endogenous. Sicker people (or those with poor risky behaviors) may be more or less likely to get insurance, depending on the operation of public and private insurance markets. In each case, the coefficients on those variables may not be the ‘true effect’, and furthermore, including these variables may bias the coefficient of education. Still, the results are an important sensitivity test: the results are suggestive about what the largest effect of “resources” broadly construed may be.

The last column in Table 1 adds these additional economic controls to the regressions (in addition to income). As a group, these variables do not add much beyond income. The additional reduction in the education coefficient is 7 percent in the smoking regression, 11 percent for obesity, and 1 percent for heavy drinking. All told, the effect of material resources in the NHIS accounts for 20 to 30 percent of the education effect. 12 The reduction of 20–30 percent may be an underestimate of the true effect, because characteristics like permanent income are measured with error, or an overstatement, because we control for variables that are themselves influenced by education.

The NHIS does not have measures of wealth or family background. Further, measures of income in the NHIS are underreported, as in many surveys. To obtain better estimates of the possible effect of resources on the education gradient (beyond background), we repeated our analysis using the Health and Retirement Study, a sample of older adults. The economic data in the HRS are generally believed to be extremely accurate and HRS has family information as well, although only four health behaviors are asked about: smoking, diet/exercise, drinking, and preventive care.

Table 2 shows the HRS results. The first column shows results controlling for demographics and a large set of socioeconomic background measures: a dummy for father alive, father's age (current or at death), dummy for mother alive, mother's age (current or at death), father's education, mother's education, religion, self reported SES at age 16, self reported health at age 16, and dad's occupation at age 16. The HRS data show similar gradients to the NHIS data, though in some cases they are smaller. For example, smoking declines by 2 percentage points with each year of education, compared with 3 percentage points in the NHIS. In part, this reduction results from the fact we have added more extensive background controls as thus would be expected. If we used only the same basic demographics available in the NHIS, we would still find somewhat smaller gradients in the HRS (available upon request). Lower coefficients might also be due to selective mortality: lower educated individuals die younger and thus are less likely to be in the HRS. Although we do not know the reason, our finding that education gradients are smaller for older individuals has been noted elsewhere (see Cutler and Lleras-Muney 2008a for references).

Table 2.

Health Behaviors, Resources, and Risk Aversion Health and Retirement Study (wave 3), Whites

| Coefficient on Years of Education |

Reduction in Education Coefficient |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Mean | N | Demographic and Background Controls |

Adding Economic Controls |

Adding Risk Aversion (in addition to economic controls) |

Economic Controls |

Adding Risk Aversion and economic controls |

| Smoking | |||||||

| Current smoker | 21% | 5036 | −0.020** | −0.018** | −0.018** | 10% | 0% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||

| Former smoker | 41% | 5036 | 0.000 | −0.001 | −0.001 | N/A | N/A |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||

| Ever smoked daily | 63% | 5217 | −0.020** | −0.018** | −0.019** | 10% | −5% |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||

| Diet/Exercise | |||||||

| BMI | 27.2 | 5144 | −0.132** | −0.115** | −0.113** | 13% | 2% |

| (0.031) | (0.031) | (0.031) | |||||

| Underweight | 2% | 5144 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0% | 0% |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |||||

| Overweight | 65% | 5144 | −0.008** | −0.008** | −0.008** | 0% | 0% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||

| Obese | 24% | 5144 | −0.009** | −0.007** | −0.007** | 22% | 0% |

| (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |||||

| Vigorous activity 3+ times/week | 53% | 5214 | 0.000 | −0.004 | −0.004 | N/A | N/A |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||

| Drinking | |||||||

| Current drinker | 58% | 5187 | 0.024** | 0.018** | 0.018** | 25% | 0% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||

| Heavy drinker (ever drinks>5 drinks--all persons) | 2% | 5187 | −0.003** | −0.003** | −0.003** | 0% | 0% |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |||||

| Preventive Care | |||||||

| Got flu shot | 39% | 5215 | 0.011** | 0.011** | 0.012** | 0% | −9% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||

| Got mammogram (women) | 73% | 2864 | 0.025** | 0.022** | 0.022** | 12% | 0% |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |||||

| Got pap smear (women) | 68% | 2858 | 0.020** | 0.016** | 0.016** | 20% | 0% |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |||||

| Got prostate test (men) | 67% | 2348 | 0.027** | 0.026** | 0.026** | 4% | 0% |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |||||

| Average Reduction in Education Coefficient | |||||||

| Unweighted standardized index, excluding preventive care | 4936 | 0.012** | 0.010** | 0.011** | 20% | −5% | |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |||||

| Unweighted percentages (outcomes w/significant gradients at baseline) | 10% | −1% | |||||

| Mortality weighted | 17% | 0% | |||||

Notes: Sample sizes are constant across columns. Data are from wave 3 of the HRS. Demographic controls include a full set of dummies for age, gender, and Hispanic origin. Socioeconomic background measures include dummy for father alive, father's age (current or at death), dummy for mother alive, mother's age (current or at death), father's education, mother's education, religion, self reported SES at age 16, self reported health at age 16, dad's occupation at age 16. Economic controls include total family income, total assets, number of individuals in the household, labor force status, region, MSA, marital status. Unweighted regression results use the methodology of Kling et al. (2007). Unweighted average reduction in education coefficient is calculated for all behaviors where the education effect without controls is statistically significant. HRS weights are used in all regressions and in calculating means. Standard errors are clustered at the person level.

(*) indicates statistically significant at the 5% (10%) level.

In the middle columns of the table, we include economic controls: labor force status, total family income, family size, assets, major activity, region, MSA, and marital status. The reduction in the education coefficient ranges from 0 percent for flu shots to 25 percent for current drinking. The average reduction in the education effect is 20 percent, and the mortality-weighted reduction is 17 percent.

In total, therefore, we estimate that material resources account for about 20 percent of the impact of higher education on health behaviors, assuming that all our measures can be thought of as material resources. This matches what we find in other data sets as well (see below). With the understanding that this estimate is likely too high (because of endogeneity), we conclude that there is a large share of the education effect still to be explained.

IV. Prices

Differences in prices or in response to prices are a second potential reason for education-related differences in health behaviors. This shows up most clearly in behaviors involving the medical system. In surveys, lower income people regularly report that time and money are major impediments to seeking medical care.13 Even given health insurance, out-of-pocket costs may be greater for the poor than for the rich – for example, their insurance might be less generous. Time prices to access care may be higher as well, if for example travel time is higher for the less educated.

A consideration of the behaviors in Table 1 suggests that price differences are unlikely to be the major explanation, however. While interacting with medical care or joining a gym costs money, other health-promoting behaviors save money: smoking, drinking, and overeating all cost more than their health-improving alternatives. It is possible that the better educated are more responsive to price than the less educated, explaining why they smoke less and are less obese. But that would not explain the findings for other behaviors which are costly but still show a favorable education gradient: having a radon detector or a smoke detector, for example. Still other behaviors have essentially no money or time cost, but still display very strong gradients: wearing a seat belt, for example.

More detailed analysis of the cigarette example shows that consideration of prices exacerbates the education differences. A number of studies show that less educated people have more elastic cigarette demand than do better educated people.14 Prices of cigarettes have increased substantially over time. Gruber (2001) shows that cigarette prices more than doubled in real terms between 1954 and 1999; counting the payments from tobacco companies to state governments enacted as part of the Master Settlement Agreement, real cigarette taxes are now at their highest level in the post-war era. Yet over the same time period, smoking rates among the better educated fell more than half, and smoking rates among the less educated declined by only one-third. For these reasons, we do not attribute any of the education gradient in health behaviors to prices.15

V. Knowledge

The next theory we explore is that education differences in behavior result from differences in what people know. Some information is almost always learned in school (advanced mathematics, for example). Other information could be more available to educated individuals because they read more. Still other information may be freely distributed, but believed more by the better educated. Most health information is of the latter type. Everyone has access to it, but not everyone internalizes it.

The possible importance of information is demonstrated by differences in how people learn about health news. Half of people with a high school degree or less get their information from a doctor, compared to one-third of those with at least some college.16 In contrast, 49 percent of people with some college report receiving their most useful health information from books, newspapers, or magazines, compared to 18 percent among the less educated.

A. Specific Health Knowledge

The 1990 NHIS asks people 12 questions about the health risks of smoking and 7 questions about drinking (see the Data Appendix). In the smoking section, respondents were asked whether smoking increased the chances of getting several diseases (emphysema, bladder cancer, cancer of the larynx or voice box, cancer of the esophagus, chronic bronchitis and lung cancer). For those under 45, the survey also asked respondents if smoking increased the chances of miscarriage, stillbirth, premature birth and low birth weight; and also whether they knew that smoking increases the risk of stroke for women using birth control. In the heart disease module individuals were asked if smoking increases chances of heart disease. Similarly, respondents were asked whether heavy drinking increased one’s chances of getting throat cancer, cirrhosis of the liver, and cancer of the mouth. For those under 45, the survey also asked respondents if heavy drinking increased the chances of miscarriage, mental retardation, low birth weight and birth defects.

These questions are important, though they do suffer a (typical) flaw – the answer in each case is yes. Still, not everyone knows this. Table 3 shows the share of questions that the average person answered correctly, separated by education group. About three-quarters of people do not answer all questions correctly (not reported in the table). This seems low, but the answers are much better on common conditions. For example, 96 percent of people believe that smoking is related to lung cancer, and 92 percent believe it is related to heart disease. On average, individuals get 81 percent of smoking questions correct and 67 percent of drinking questions correct. There are some differences in responses by education, but often these are not that large. For example, 91 percent of high school dropouts report that smoking causes lung cancer, compared to 97 percent of those with a college degree. For heart disease, there is a bigger difference: 84 percent of high school dropouts versus 96 percent of the college educated believe smoking is related to heart disease.

Table 3.

Explanations for Health Differences

| Mean by Education |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure (Data set) | N | Mean (all) |

<High School |

High School |

Some College |

College + | Min | Max |

| Knowledge | ||||||||

| Health Knowledge (NHIS) | ||||||||

| Smoking questions (percent correct) | 30,469 | 81% | 74% | 81% | 83% | 86% | 0 | 1 |

| Drinking questions (percent correct) | 30,468 | 67% | 62% | 66% | 69% | 70% | 0 | 1 |

| AFQT (NLSY, 2002 weights) | 4,709 | 52.7 | 17.8 | 41.4 | 58.4 | 72.8 | 1 | 99 |

| Utility Function Parameters | ||||||||

| Discounting (MIDUS) | ||||||||

| Life satisfaction current (0=worst; 10=best) | 2,561 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 7.8 | 0 | 10 |

| Life satisfaction future (0=worst; 10=best) | 2,561 | 8.3 | 7.8 | 8.4 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 0 | 10 |

| Plan for the future (percent agree) | 2,547 | 43% | 32% | 42% | 41% | 50% | 0 | 1 |

| Risk aversion (HRS) (1=least; 4=most) | 5,217 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 1 | 4 |

| Discounting (SOS) | ||||||||

| Impulsivity Index (higher values correspond to more impulsive) | 556 | 35.6 | 38.7 | 36.1 | 35.2 | 34.8 | 20 | 54 |

| Financial tradeoff variables | ||||||||

| Win $1k now vs. $1.5k in a year (percent prefer now) | 561 | 62% | 75% | 71% | 61% | 53% | 0 | 1 |

| Win $20 now vs. $30 in a year (percent prefer now) | 561 | 79% | 92% | 83% | 78% | 73% | 0 | 1 |

| Lose $1.5k in a year vs. $1k now (percent prefer in a year) | 545 | 47% | 53% | 45% | 51% | 43% | 0 | 1 |

| Lose $30 in a year vs. $20 now (percent prefer in a year) | 551 | 43% | 53% | 42% | 42% | 43% | 0 | 1 |

| Planning horizon for savings and spending (years) | 564 | 6.93 | 5.47 | 5.29 | 6.57 | 8.62 | 0 | 20 |

| Spent a great deal of time on financial planning (percent agree) | 562 | 58% | 45% | 54% | 55% | 66% | 0 | 1 |

| Spent a great deal of time planning vacation (percent agree) | 556 | 59% | 52% | 56% | 60% | 62% | 0 | 1 |

| Health discounting questions | ||||||||

| Extra healthy days 1 year from now equal to 20 healthy days now | 351 | 61.2 | 92.4 | 68.8 | 83.5 | 34.8 | 0 | 365 |

| Extra healthy days 5 years from now equal to 20 healthy days now | 344 | 79.7 | 101.6 | 77.7 | 103.3 | 58.1 | 0 | 365 |

| Extra healthy days 10 years from now equal to 20 healthy days now | 340 | 94.8 | 105.3 | 92.2 | 112.1 | 80.1 | 0 | 365 |

| Extra healthy days 20 years from now equal to 20 healthy days now | 330 | 105.5 | 92.3 | 101.5 | 128.7 | 90.7 | 0 | 365 |

| Personality Scores | ||||||||

| Self control, efficacy, depression (NLSY 2002 weights) | ||||||||

| Rosenberg self-esteem score (1980) (0=min; 30=max) | 4709 | 22.1 | 19.7 | 21.3 | 22.6 | 23.5 | 0 | 30 |

| Rosenberg self-esteem score (1987) (0=min; 30=max) | 4709 | 22.8 | 20.1 | 22.1 | 23.3 | 24.2 | 0 | 30 |

| Pearlin score of self control (1992) (0=min; 28=max) | 4709 | 21.8 | 19.9 | 21.5 | 22.1 | 22.4 | 0 | 28 |

| Shy at age 6 (percent extremely or somewhat) | 4709 | 57% | 63% | 61% | 57% | 52% | 0 | 1 |

| Shy as an adult (1985) (percent extremely or somewhat) | 4709 | 26% | 35% | 26% | 24% | 23% | 0 | 1 |

| Rotter scale of control over life (1979) (1=internal; 16=external) | 4709 | 8.7 | 9.3 | 9.0 | 8.6 | 8.2 | 1 | 16 |

| Depression scale (1992) (0=minimum; 21=maximum) | 4709 | 3.7 | 5.0 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 0 | 21 |

| Depression scale (1994) (0=minimum; 21=maximum) | 4709 | 3.4 | 4.6 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 0 | 21 |

| Personality (MIDUS) | ||||||||

| Depression scale (0=no; 7=maximum) | 2,561 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0 | 7 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder (0=no; 10=maximum) | 2,561 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0 | 10 |

| Positive affect (1=all of time; 5=none of time) | 2,555 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 1 | 5 |

| Negative affect (1=all of time; 5=none of time) | 2,553 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1 | 5 |

| Control (1=lowest; 7=highest) | 2,553 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 0 | 3 |

| Depression scale (SOS, 0=no; 9=maximum) | 632 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 0 | 9 |

| Socialization (MIDUS) | ||||||||

| Friends support (positive) scale (1=least; 4=most) | 2,551 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 1 | 4 |

| Friends strain (negative) scale (1=least; 4=most) | 2,552 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1 | 4 |

| Family support (positive) scale (1=least; 4=most) | 2,548 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 1 | 4 |

| Family strain (negative) scale (1=least; 4=most) | 2,545 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 1 | 4 |

| Spouse/partner support (positive) scale (1=least; 4=most) | 1,838 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 1 | 4 |

| Spouse/partner strain (negative) scale (1=least; 4=most) | 1,838 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1 | 4 |

| Social integration (3=min; 21=max) | 2,550 | 13.8 | 12.9 | 13.7 | 13.6 | 14.5 | 3 | 21 |

| Social contribution (3=min; 21=max) | 2,550 | 15.2 | 13.1 | 14.4 | 15.4 | 17.2 | 3 | 21 |

| Stress (MIDUS) | ||||||||

| Worrying describes you (percent agree) | 2,556 | 53% | 59% | 56% | 51% | 48% | 0 | 1 |

| All stress (answered yes to 3 stress questions) | 1,816 | 7% | 7% | 6% | 6% | 8% | 0 | 1 |

| Any stress (answered yes to any stress question) | 1,818 | 47% | 36% | 43% | 51% | 54% | 0 | 1 |

Weights used in all means. The appendix has specific questions and coding information.

Table 4 examines how important knowledge differences are for smoking and drinking. The first columns in the table show the gradient in poor behaviors associated with education when controlling for socioeconomic factors and income but not knowledge. The coefficients are roughly similar to those reported in the last specification of Table 1, although from a decade earlier.

Table 4.

The Impact of Health Knowledge on Health Behaviors 1990 National Health Interview Survey, whites ages 25 and over

| Regression Coefficients Without Knowledge Questions |

Regression Coefficients With Knowledge Questions |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Mean | N | Years of Education |

Years of Education |

Percent Questions Correct |

Reduction in Education Coefficient |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Current smoker | 26% | 29929 | −0.021** | −0.018** | −0.318** | 17% |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.012) | ||||

| Former smoker | 28% | 29929 | 0.003** | 0.001 | 0.156** | 63% |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.013) | ||||

| Made serious attempt to quit (smokers) | 64% | 7602 | 0.011** | 0.008** | 0.24** | 28% |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.024) | ||||

| Number cigs a day (smokers) | 21.5 | 15388 | −0.327** | −0.327** | 0.056 | 0% |

| (0.046) | (0.047) | (0.554) | ||||

| Alcohol | ||||||

| Drink at least 12 drinks per year | 73% | 29869 | 0.010** | 0.010** | −0.044** | −3% |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.009) | ||||

| Heavy drinker (usually drinks>=5--all persons) | 5% | 30222 | −0.005** | −0.005** | −0.011** | 1% |

| (0.0005) | (0.0005) | (0.005) | ||||

| Number drinks when drinks (drank in last two weeks) | 2.4 | 13845 | −0.105** | −0.103** | −0.189** | 1% |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.049) | ||||

| Average Reduction in Education Coefficient | ||||||

| Unweighted standardized index | 29836 | 0.022** | 0.021** | 5% | ||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |||||

| Unweighted percentages (outcomes w/significant gradients at baseline) | 18% | |||||

| Mortality weighted | 12% | |||||

Notes: The sample is aged 25 and older. Sample sizes are constant across columns. All regressions include a full set of age dummies, gender, Hispanic origin, family income, family size, major activity, region, MSA, and marital status. The smoking questions ask whether smoking increases a person's risk for 7 diseases, for 4 pregnancy complications, and for stroke incidence while on birth control. The drinking questions ask whether alcohol increases the risk for 3 diseases and 4 pregnancy complications. Unweighted regressions use the methodology of Kling et al. (2007).

(*) indicates statistical significance at the 5% (10%) level.

As the next columns show, people who answer more smoking questions correctly are less likely to smoke. Indeed, answering all questions correctly eliminates smoking. Similarly, people who answer drinking questions correctly are less likely to drink heavily. But knowledge has only a modest impact on the education gradient in smoking and little impact on the gradient in drinking. The coefficient on years of education in explaining current smoking declines by 17 percent with the knowledge questions included, while the coefficient for drinking is essentially unaffected. The average reduction is between 5 and 18 percent, depending on the metric. These results thus suggest that specific knowledge is a source, but not the major source, of differences in smoking and drinking. These results are in line with those found by Meara (2001) and interestingly with those reported by Kenkel (1991), who attempted to account for the possibility that health knowledge is endogenous.17

Cognitive dissonance suggests an important caveat to these findings: individuals may differ in the extent to which they report they know about what is harmful as a function of their habits (for example smokers might report they don’t know as much). In the case of smoking Viscusi (1992) suggests that both smokers and non-smokers vastly overestimate the risks of smoking (though other studies find different results, see Schoenbaum 1997 for example). Most importantly here, it is not known whether these biases differ by education.

One potential concern about the knowledge questions is that we do not know the extent to which the answers reflect the depth of individuals’ beliefs. People may know what the correct answer is without believing it that strongly. For decades, tobacco producers sought to portray the issue of smoking and cancer as an unresolved debate, rather than a scientific fact. This might have had a greater impact on the beliefs of the less educated, for whom the methods of science are less clear.18

We have only a single piece of evidence along these lines. We examined self-reported questions from the Motor Vehicle Occupant Safety Survey (MVOSS), which asks people about the value of wearing a seat belt (results available upon request).19 Respondents are asked to strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree with two questions about seat belt use: “If I were in an accident, I would want to have my seat belt on,” and “Seat belts are just as likely to harm you as help you.” A claim that seat belts harm people in an accident is commonly expressed by those who oppose mandatory seat belt legislation, somewhat akin to the ‘debate’ about the harms of tobacco.

Answers to the question about wanting a seat belt in an accident are uniformly high; 89 to 97 percent of people strongly or somewhat agree that they would want a seat belt on if they were in an accident. But there is still residual doubt about the value of a seat belt that is much more common among the less educated. Fifty-five percent of people with less than a high school degree strongly or somewhat agree that seat belts are just as likely to harm as help them, compared to only 17 percent of those with a college degree.20 These patterns suggest that superficially, individuals of all education levels have received the main public health message that one should wear a seat belt, and they report as much when asked. But uneducated individuals seem less certain of the validity of that information, and that becomes clear when the questions are asked slightly differently. Furthermore, we can “explain” a larger share of the effect of education on seat belt use when we include these alternative measures of “depth of knowledge”.

We cannot further examine this possibility here. We simply note that our results suggest that providing factual information alone may not be sufficient to make individuals change their behavior, and that differences in information alone are not sufficient to explain much of the education gradient in health behavior.

B. Conceptual Thinking

The tobacco and seat belt examples suggest that information processing, more than (or in addition to) exposure to knowledge, may be the key to explaining education gradients in behaviors. Similar arguments have been made to explain why education raises earnings in the labor market. Nelson and Phelps (1966) first hypothesized that “education is especially important to those functions requiring adaption to change” and that “the rate of return to education is greater the more technologically progressive is the economy.” This was echoed by Schultz (1975), who proposed that education enhances individuals’ “ability to deal with disequilibria” and Rosenzweig (1995), who argued that education improves individuals’ ability to “decipher” that information. All of these ideas can easily be applied in the context of health behaviors.

The existing literature provides some suggestions that cognitive ability is related to education gradients. For example more educated people are better able to use complex technologies/treatments than less educated individuals. Goldman and Smith (2002) document that the more educated are more likely to comply with HIV and diabetes treatments, which are extremely demanding. Rosenzweig and Schultz (1989) similarly show that contraceptive success rates are identical for all women for “easy” contraception methods such as the pill, but the rhythm method is much more effective among educated women. The more educated appear to be better at learning. Lleras-Muney and Lichtenberg (2005) find that, controlling for insurance, the more educated are more likely to use drugs more recently approved by the FDA, but this is only true for individuals who repeatedly purchase drugs for a given condition, so for those who have an opportunity to learn. Similarly Lakdawalla and Goldman (2005) and Case, Fertig and Paxson (2005) find that the health gradient is larger for chronic diseases, where learning is possible, than for acute diseases.

To examine the possibility that cognitive ability lies behind the education gradient in behavior, we turn to measures of general cognition.21 The NLSY administered the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) to all participants in 1979. The ASVAB is the basis for the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT) but it contains many more dimensions than are scored in the AFQT. We include the test results for all 10 subjects, namely science, arithmetic, mathematical reasoning, word knowledge, paragraph comprehension, coding speed, numeric operations speed, auto and shop information, mechanical competence, and electronic information.22 Table 3 shows that those with a college degree or more scored much higher in the AFQT (73rd percentile on average) compared to high school dropouts (18th percentile).

Table 5 shows the relation between education, ASVAB scores, and a variety of health behaviors (smoking, diet, exercise, alcohol consumption, illegal drug use and preventive care). We use behaviors from relatively recent survey years, 1998 or 2002. The respondents thus range in age from the mid-30s to the mid-40s. Mean rates of favorable and poor health behaviors are shown in the first column; these percentages are close to those for the NHIS, particularly when restricted to the same ages.

Table 5.

The Impact of Cognitive Ability and Personality on Education Gradients National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979, Whites

| Coefficient on Years of Education |

Reduction in Education Coefficient |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addition to Economic and Family Background controls |

Addition to Income and Family Background |

|||||||||

| Measure | Mean | N | Year | Demographic and family background Controls |

Economics controls |

ASVAB Scores |

Personality Scales |

Economic controls |

ASVAB Scores |

Personality Scales |

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| Current Smoker | 27% | 5052 | 1998 | −0.049** | −0.047** | −0.039** | −0.045** | 5% | 15% | 4% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||||

| Former Smoker | 21% | 5053 | 1998 | 0.0028 | 0.0027 | 0.0003 | 0.0014 | 3% | 86% | 49% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||||

| Diet/Exercise | ||||||||||

| BMI | 27.53 | 4548 | 2002 | −0.197** | −0.169** | −0.126** | −0.156** | 14% | 22% | 7% |

| (0.039) | (0.040) | (0.046) | (0.040) | |||||||

| Underweight | 1% | 4548 | 2002 | −0.00106 | −0.00067 | −0.00087 | −0.00094 | 37% | −19% | −25% |

| (0.0008) | (0.0008) | (0.0009) | (0.0008) | |||||||

| Overweight | 64% | 4548 | 2002 | −0.014** | −0.013** | −0.006 | −0.013** | 4% | 51% | 1% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.003) | |||||||

| Obese | 27% | 4548 | 2002 | −0.016** | −0.014** | −0.012** | −0.013** | 17% | 9% | 3% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.003) | |||||||

| Vigorous exercise | 42% | 3730 | 1998 | 0.032** | 0.030** | 0.029** | 0.024** | 8% | 1% | 17% |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.004) | |||||||

| Light exercise | 79% | 3729 | 1998 | 0.019** | 0.017** | 0.010** | 0.013** | 8% | 38% | 21% |

| (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.003) | |||||||

| Alcohol | ||||||||||

| Current drinker | 60% | 4704 | 2002 | 0.016** | 0.010** | −0.001 | 0.006* | 40% | 64% | 24% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.003) | |||||||

| Heavy drinker (mean # of drinks>=5--all population) | 8% | 4704 | 2002 | −0.011** | −0.009** | −0.008** | −0.009** | 16% | 10% | −2% |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |||||||

| Frequency of heavy drinking past month (drinkers only) | 97% | 2751 | 2002 | −0.141** | −0.132** | −0.106** | −0.126** | 7% | 18% | 4% |

| (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.023) | (0.020) | |||||||

| Number of drinks (drinkers only) | 264% | 2746 | 2002 | −0.154** | −0.134** | −0.087** | −0.125** | 13% | 30% | 6% |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.019) | (0.017) | |||||||

| Illegal Drugs | ||||||||||

| Never tried pot | 34% | 5036 | 1998 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.008** | 0.003 | −3% | −339% | −68% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||||

| # times smoked pot in life>50 | 26% | 5036 | 1998 | −0.014** | −0.014** | −0.017** | −0.014** | 3% | −27% | −4% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||||

| Never tried cocaine | 73% | 5048 | 1998 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.007** | 0.000 | 123% | 1906% | 117% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||||

| # times used cocaine in life>50 | 7% | 5048 | 1998 | −0.006** | −0.005** | −0.008** | −0.006** | 13% | −67% | −17% |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |||||||

| Preventive Care Use | ||||||||||

| Regular doctor visit last year | 57% | 4709 | 2002 | 0.005** | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 36% | −57% | 35% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||||

| OBGYN visit last year | 58% | 2424 | 2002 | 0.027** | 0.021** | 0.023** | 0.021** | 22% | −9% | −1% |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.005) | |||||||

| Other | ||||||||||

| Read food labels | 46% | 4709 | 2002 | 0.035** | 0.034** | 0.020** | 0.031** | 1% | 40% | 10% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.003) | |||||||

| Average Reduction in Education Coefficient | ||||||||||

| Unweighted standardized index, excluding OBGYN visits, 2002 | 2002 | 0.033** | 0.028** | 0.020** | 0.026** | 14% | 27% | 7% | ||

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.003) | |||||||

| Unweighted standardized index, 1998 | 1998 | 0.021** | 0.020** | 0.018** | 0.018** | 4% | 10% | 13% | ||

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.003) | |||||||

| Unweighted percentages (outcomes w/significant gradients at baseline) | 14% | 9% | 7% | |||||||

| Unweighted percentages, excluding illegal drugs (outcomes w/significant gradients at baseline) | 15% | 18% | 10% | |||||||

| Mortality weighted | 12% | 15% | 4% | |||||||

Reading food labels is an indicator for whether the person always or often reads nutritional labels when buying food for the first time. Frequency of heavy drinking reports the number of times in the last month that the respondent had 6 or more drinks in a single occasion. Demographic controls include a full set of dummies for age, and gender. Economic controls include family income, family size, regio MSA, marital status. Background controls include whether respondent is American, whether mom is America, whether dad is American, familiy income in 1979, mother's education, father's education, whether lived with dad in 1979, whether the person had tried marijuana by 1979, whether the person had damaged property by 1979, whether the person had fought in school by 1979, and whether the person had been charged with a crime by 1980 and height. Personality scores include the Rosen self esteem score in 1980 and 1987, the Pearlin score of self control in 1992, the Rotter scale of control over one's life in 1979, whether the person considered themselves shy at age 6 and as an adult (in 1985), and history of depression (the CESD, measured in 1992 and 1994). Sample contains individuals with no missing education or AFQT. Indicator variables for missing controls are included whenever any other control is missing.

Unweighted regressions use the methodology in Kling et al. (2007). NLSY weights are used in all regressions and in calculating means.

(*) indicates statistical significance at the 5% (10%) level.

We first document education gradients and the effects of economic resources in this sample. The first column shows the impact of education on behavior including only demographic and family background controls. The impact of education on behavior is large, often times larger than the NHIS. For example, each year of education is associated with a 4.9 percent lower probability of smoking and a 1.6 percent lower chance of being obese. The next column includes economic resources. There is generally a significant impact of these variables on the education gradient. Using the mortality weights noted above we estimate that 12 percent of the education gradient in mortality is explained with economic controls (alternative averages yield similar results).

The third column includes the individual ASVAB scores, in addition to the income and family background. The additional impact of these controls is substantial, though it varies by outcome. ASVAB scores account for an additional 15 percent of the education gradient in smoking, 9 percent of the gradient in obesity, and 10 percent of the gradient in heavy drinking. The overall average reduction varies depending on whether the illegal drug use variable is included or not. Including test scores exacerbates the education gradients in illegal drug use. It is not clear why this is the case, and is not true with the British data (discussed below).23 We also find that adding cognition increases the education gradient in preventive care. The reduction is about 20 percent without those variables but near zero (or negative) with those variables. Using the mortality weights, ASVAB scores explain 15 percent of the education effect. A central concern about these results is causality: is cognitive ability affected by education, or does cognitive ability lead people to become more educated? We return to this in Section IX.

While the estimates differ across specifications, our overall summary is that together knowledge and cognition account for 5 to 30 percent of the education gradient in behaviors, although cognition measures tend to increase education gradients in illegal drug use and preventive care, a puzzle which we do not resolve here.

VI. Utility Function Characteristics: Discount Rates, Risk Aversion and the Value of the Future

The most common economic explanation for different behaviors is tastes. In our framework, tastes take the form of differences in discount rates, the value of the future, or risk aversion. The source of differences in utility functions is not clear. Education may lead people to have lower discount rates (Becker and Mulligan, 1997): for example if education raises future income, individuals have an incentive to invest in lowering their discount rate. Education may also lead people be more risk averse. Alternatively, education may itself be the product of differences in utility functions (Fuchs, 1982), which may be distributed randomly, may be inherited, or may be a product of the early childhood environment.

Some preliminary evidence suggests that differences in utility functions cannot be the primary explanation for differences in health behaviors. Were the difference in health behaviors driven by fixed aspects of individuals, we would expect that health behaviors would be highly correlated across individuals: people who care about their health would maximize longevity in all ways. However, while almost all health behaviors are related to education, these behaviors are not particularly highly correlated at the individual level. Cutler and Glaeser (2005) show that the correlation between different health behaviors is generally about 0.1. Still, we can investigate this hypothesis more directly.

We start first with the value of the future. Probably the best measures of discounting and of the value of the future come from the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States, or MIDUS, a sample of people aged 25–74 in the mid-1990s.24 MIDUS has several measures of the value of the future. In an overall summary question about future expectations, individuals are asked “Looking ahead ten years into the future, what do you expect your life overall will be like at that time?”25 The same question is asked about current situation, which we include as well. There are some questions that can also be used as proxies for discount rates. Individuals were asked whether they agreed with the following statement: “I live one day at a time and don't really think about the future.” We code those who strongly disagree as being able to plan for the future. Theory suggests that that people with higher future utilities or who are able to plan will invest more in health, and possibly that there will be an interaction between the two (those who value the future and are good at planning will invest even more in health).

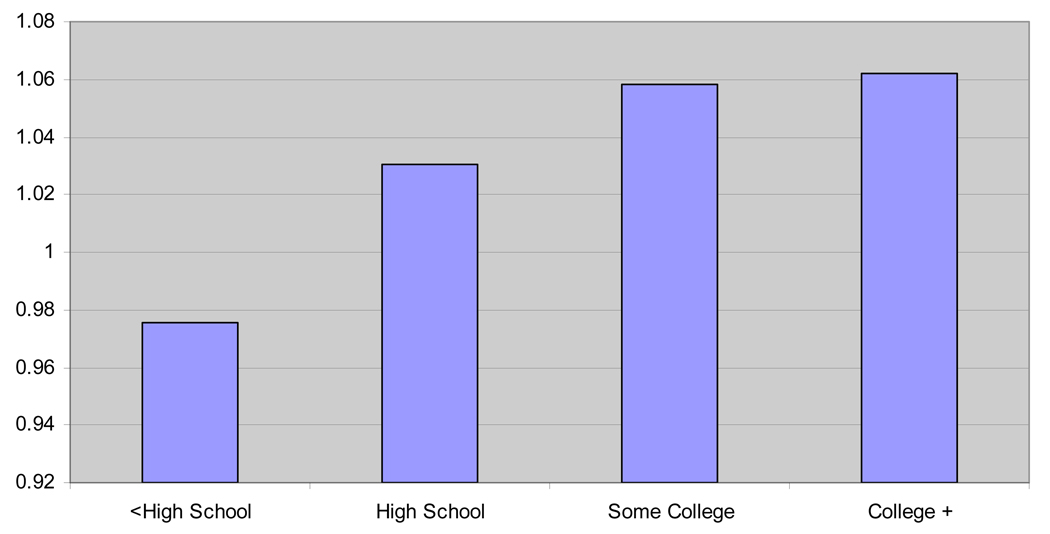

Table 3 shows summary measures of these variables by education. High school dropouts are indeed less future oriented than those with more than a college degree, but there appears to be no difference between high school graduates and those with some college only. The more educated are equally satisfied with their current life as the least educated, and those with some college report the lowest current satisfaction. The relationship between education and future satisfaction is also not linear, being the highest among the college educated, followed by high school graduates, those with some college and high school dropouts. Although these satisfaction measures are not very highly correlated with education, Figure 2 shows that the ratio of future to current satisfaction is monotonically increasing in education—the more educated value the future more relative to the present.26

Figure 2. Ratio of future to current satisfaction, by education.

Note: Data are from the MIDUS survey.

MIDUS asks about some measures of health, though not as many as dedicated health surveys. It includes smoking and weight, though not alcohol consumption. Questions are also asked about general health behavior, illegal drug use, and receipt of preventive care.

Table 6 shows results from the MIDUS survey. The first columns report means of the independent variables. Where we can compare, the means are close to the NHIS. Using just demographic and family background measures as controls (the first column of regression coefficients) the education coefficients are also similar, if anything slightly larger. Each year of education reduces smoking by 3.5 percent and obesity by 1.6 percent.

Table 6.

Discounting and the Value of the Future National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States, Whites, 1995–1996

| Coefficient on Years of Education |

Reduction in Education Coefficient |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addition to Income and Family Background |

Addition to Income and Family Background |

||||||||||

| Dependent Variable | Mean | N | Basic Demographics and family background |

Economic controls |

Current and Future Life Satisfaction and Future Planning |

Personality | Social integration |

Economic controls |

Current and Future Life Satisfaction and Future Planning |

Personality | Social integration |

| Smoking | |||||||||||

| Current smoker | 25% | 2545 | −0.035** | −0.032** | −0.032** | −0.032** | −0.029** | 9% | 1% | −1% | 9% |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |||||||

| Former smoker | 29% | 2546 | −0.009* | −0.008 | −0.008 | −0.006 | −0.008 | 12% | −2% | 18% | −2% |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |||||||

| Average # of cigs per day | 26.1 | 1372 | −1.013** | −0.955** | −0.949** | −0.955** | −0.945** | 6% | 1% | 0% | 1% |

| (0.240) | (0.245) | (0.244) | (0.254) | (0.267) | |||||||

| Ever tried to quit smoking (if smoker) | 83% | 585 | −0.006 | −0.004 | −0.005 | −0.006 | −0.004 | 31% | −11% | −26% | 3% |

| (0.011) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | |||||||

| Diet/Exercise | |||||||||||

| BMI | 26.5 | 2440 | −0.148** | −0.101* | −0.097 | −0.100 | −0.080 | 32% | 3% | 1% | 14% |

| (0.059) | (0.059) | (0.059) | (0.059) | (0.062) | |||||||

| Underweight | 3% | 2440 | 0.00022 | 0.0027* | 0.0028* | 0.003** | 0.003 | −13% | −4% | 4% | 0% |

| (0.0015) | (0.0016) | (0.0016) | (0.0015) | (0.0017) | |||||||

| Overweight | 56% | 2440 | −0.009 | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.004 | −0.002 | 56% | 5% | −6% | 24% |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |||||||

| Obese | 21% | 2440 | −0.016** | −0.013** | −0.012** | −0.013** | −0.012** | 18% | 3% | 2% | 3% |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |||||||

| # of times per month engages in vigorous exercise | 5.9 | 2546 | 0.164** | 0.114** | 0.103* | 0.113** | 0.072** | 30% | 7% | 1% | 26% |

| (0.055) | (0.057) | (0.056) | (0.057) | (0.060) | |||||||

| Lose 10 lbs due to lifestyle | 22% | 2466 | −0.012** | −0.011** | −0.012** | −0.012** | −0.012** | 10% | −4% | −5% | −3% |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |||||||

| Illegal Drugs | |||||||||||

| Used cocaine, past 12 months | 1% | 2538 | −0.001 | −0.002* | −0.002* | −0.003* | −0.002 | −77% | −8% | −23% | 0% |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |||||||

| Used marijuana, past 12 months | 6% | 2536 | 0.000 | −0.002 | −0.003 | −0.003 | −0.003 | −2100% | 200% | −500% | −300% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||||

| Other illegal drug used, past 12 months | 10% | 2524 | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.004 | −0.001 | −0.001 | 26% | 8% | 37% | 47% |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||||

| Preventive Care | |||||||||||

| Take vitamin at least few times per week | 48% | 2546 | 0.024** | 0.022** | 0.022** | 0.022** | 0.020** | 7% | 1% | −1% | 10% |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |||||||

| Had blood pressure test, past 12 months | 67% | 2516 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 46% | −9% | 14% | −9% |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |||||||

| Doctor visit, past 12 months | 69% | 2496 | 0.011** | 0.009* | 0.009* | 0.009 | 0.010 | 15% | 3% | −2% | −3% |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |||||||

| General Behavior | |||||||||||

| Work hard to stay healthy (1–7 scale, 1 is better) | 2.4 | 2546 | 0.014 | 0.011 | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.032** | 20% | −27% | 16% | −149% |

| (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | |||||||

| Effort put on health (0–10 scale, 10 is better) | 7.1 | 2546 | −0.008 | −0.007 | −0.014 | −0.003 | −0.034 | 17% | −103% | 41% | −355% |

| (0.023) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.025) | |||||||

| Average | |||||||||||

| Unweighted standardized index | 2279 | 0.018** | 0.015** | 0.014** | 0.015** | 0.012** | 14% | 8% | 1% | 22% | |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |||||||

| Unweighted percentages (outcomes w/significant gradients at baseline) | 18% | 1% | 1% | 7% | |||||||

| Mortality weighted | 11% | 1% | 1% | 7% | |||||||