Abstract

This review addresses new concepts related to the importance of how cells within the cardiovascular system respond to matricryptic sites generated from the extracellular matrix (ECM) following tissue injury. A model is presented whereby matricryptic sites exposed from the ECM result in activation of multiple cell surface receptors including integrins, scavenger receptors, and toll-like receptors which together are hypothesized to coactivate downstream signaling pathways which alter cell behaviors following tissue injury. Of great interest are the relationships between matricryptic fragments of ECM called matricryptins and other stimuli that activate cells during injury states such as released components from cells (DNA, RNA, cytoskeletal components such as actin) or products from infectious agents in innate immunity responses. These types of cell activating molecules, which are composed of repeating molecular elements, are known to interact with pattern recognition receptors that are, i) expressed from cell surfaces, ii) released from cells following tissue injury, or iii) circulate as components of plasma. Thus, cell recognition of matricryptic sites from the ECM appears to be an important component of a broad cell and tissue sensory system to detect and respond to environmental cues generated following varied types of tissue injury.

Keywords: Extracellular matrix, matricryptic sites, matricryptins, integrins, scavenger receptors, toll-like receptors, pattern recognition receptors

Introduction

Recent years has witnessed an explosion of knowledge concerning how cells respond to cues from their surroundings including growth factors, cytokines, extracellular matrix and components derived from microorganisms that infect cells and tissues. It appears clear that broad and overlapping mechanisms exist to sense changes in the extracellular environment to respond to the varied types of tissue injuries which occur. A key system that responds to tissue injury is the cardiovascular system in that it controls both the delivery of plasma components and inflammatory cells to sites of tissue injury. Thus, the cardiovascular system is particularly fundamental in controlling tissue injury by controlling oxygen tension, blood flow, vascular permeability, hemostasis, inflammation, and the response to local and systemic infections. This review will address new insights into how cryptic sites within extracellular matrix molecules (i.e. matricryptic sites) [1] play a role in such tissue injury responses and how they should be considered as a component of a broad sensory system including detection of cellular injury (via recognition of cell products such as DNA, RNA, actin, lipids, etc) and microbial, viral, or fungal products (via lipopolysaccharide, lipotechoic acid, formyl methionyl peptides, single or double stranded RNA, etc). We will also consider these issues in the context of the cardiovascular system, due to its central importance in controlling tissue injury but also its ability to regulate and propagate such signals from local to systemic responses.

Matricryptic sites within extracellular matrix molecules control tissue injury responses

A decade ago, we proposed the name matricryptic sites as newly exposed recognition sites that are revealed in ECM molecules when perturbations occur to such molecules [1]. Importantly, we were careful to include both proteins and carbohydrates such as glycoaminoglycans since they are critical regulators of ECM function as well. We also coined the term matricryptins which refers to fragments of ECM molecules that have biological functions. Others have utilized the term matrikines for these fragments [2]. A further point is that matricryptic sites are exposed in ECM molecules for a variety of reasons including; i) enzymatic degradation, ii) mechanical forces being exerted on the molecules, iii) adsorption and heterotypic binding to other molecules, iv) multimerization and self-assembly reactions, and v) denaturation, for example, during thermal or oxidant-induced conformational changes [1]. The exposure of matricryptic sites within intact ECM molecules or following fragmentation as expressed by matricryptins leads to biological consequences such as; i) ECM assembly and multimerization; ii) assembly of wound repair scaffolds consisting of ECM molecules with associated growth factors, cytokines, proteinases and proteinase inhibitors and; finally, iii) stimulation of receptor-mediated signal transduction to control cellular responses to tissue injury [1].

Many recent studies have identified new matricryptic sites and have further elucidated their functional relevance [2–8]. A critical ECM protein which dramatically illustrates the role of matricryptic sites is fibronectin [1,9–14]. Fibronectin has many known functions including self-assembly, multimerization through protein-protein binding, disulfide exchange and covalent binding, heterotypic interactions with native and denatured collagens, fibrinogen/fibrin, and glycosaminoglycans such as heparan sulfate [1] as well as important interactions with integrins and growth factors such as VEGF [15]. In each case, the interactions of fibronectin with itself, or its other binding partners are markedly controlled by matricryptic sites within domains that are unfolded to expose new binding sites [11]. Recent and past work suggest that mechanical forces exerted on fibronectin by cells (through fibronectin-integrin-cytoskeletal interactions) leads to the exposure of matricryptic sites that further regulate fibronectin function and signal transduction events mediated through cell surface receptors [11,16]. Fibronectin also is highly susceptible to proteolytic degradation that leads to functional matricryptins being generated and which induce signal transduction.

A critically important matricryptic site is Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) which is present in fibronectin and many other ECM proteins such as collagens, vitronectin and osteopontin [1]. In most cases, it is not exposed within ECM proteins unless they adsorb to matrices, are proteolytically modified, or self-assemble [1]. Recent work shows that the RGD site in fibronectin is required for development through its interactions with α5β1 and various αv integrins [17]. Interestingly, it is not absolutely required for fibronectin matrix assembly since there are other integrin binding sites within fibronectin such as an additional novel site recognized by αvβ3 [17]. Thus, combinations of integrins participate in stimulating the mechanical forces necessary to expose matricryptic sites controlling both self-assembly and disulfide cross-linking. A recent finding suggests that soluble fibronectin can bind α5β1 (perhaps through the fibronectin synergy site) but not αvβ3 on fibroblasts showing that the RGD site is not exposed in soluble fibronectin [18]. Adsorption of fibronectin leads to exposure of its RGD site allowing either αvβ3 or α5β1 to bind to this site. An additional finding which is of great interest is the ability of fibronectin to specifically bind VEGF [15], a fundamental regulator of tissue vascularization. Fibronectin, the fibronectin-binding integrin, α5β1, and VEGF are all required for vascular development. VEGF binds to the C-terminal Hep2 domain of fibronectin [15] which is near its RGD sequence (also a matricryptic site). Heparin binding to fibronectin strongly induces binding to VEGF in a manner which does not require the retention of heparin suggesting that heparin induces a matricryptic site which then binds VEGF [15]. This interesting work suggests important cosignaling possibilities whereby the adjacent RGD site binding could bind α5β1 and VEGF could signal through VEGFR2 to create unique signals to vascular cells (possibly through integrin/growth factor receptor interactions). Considerable new information suggests that ECM-associated growth factors may present unique signals compared to their soluble counterparts to control cell signaling [19].

Receptors for matricryptic sites include integrins, and two classes of pattern recognition receptors, scavenger receptors and toll-like receptors

A number of linear peptide sequences containing RGD (binds αv integrins), LDV (α4β1 and α9β1) and SVVYGLR (α4β1 and α9β1) bind integrins and are all likely to be matricryptic [1,20–22]. Interestingly, LDV was identified in the CS-1 alternative splice variant of fibronectin and SVVYGLR is directly adjacent to a thrombin proteolytic cut site in osteopontin which likely exposes this site, as well as an adjacent RGD sequence, and a separate α4β1-binding peptide sequence (i.e. three distinct integrin binding sites) in this N-terminal matricryptin fragment of osteopontin [21]. Also, many years ago, my laboratory first reported that denatured proteins show affinity for the leukocyte β2 integrins, αMβ2 and αXβ2, but not αLβ2 [23]. Later work revealed that the von Willebrand factor A domain structure of αM directly binds to denatured proteins [24,25]. This latter finding that integrins bind denatured or modified proteins is similar to the affinity of a different class of leukocyte receptors, scavenger receptors (SRs) for such molecules.

SRs are composed of a diverse set of receptors of which the major classes are represented as class A and class B [26–28]. Class A SRs are homotrimeric receptors that are type II transmembrane proteins that are expressed by a variety of cells including leukocytes such as macrophages and dendritic cells as well as endothelial cells which express unique patterns or members of the family. They are characterized by a collagenous triple helical domain with affinity for polyanionic sequences and which represents the binding sites for denatured or modified proteins such as modified LDLs (oxidized or acetylated) and other ligands. Class B receptors are type III transmembrane proteins and consist of CD36, a receptor for modified LDLs and the matricellular ECM protein, thrombospondin-1, and SR-B1, an important receptor controlling HDL uptake and cholesterol delivery to tissues [26,28]. In general terms, SRs are involved in taking up microorganisms and tissue debris through phagocytic uptake mechanisms. Of interest is that both αMβ2 and αXβ2 as well as β3 integrins, such as αvβ3, also participate in phagocytic uptake in macrophages by recognizing opsonic material (including denatured and modified proteins as well as fibronectin). This suggests the possibility that integrins and scavenger receptors work together and perhaps coassociate to mediate such phenomena. Uptake of oxidized lipids is thought to be an important pathogenic feature of atherosclerosis [29,30]. SRs such as SR-A, CD36 and LOX-1, are known to play critical roles in the development of atherosclerotic lesions [28,30]. Endothelial cells are also known to participate in uptake of oxidized LDL through SRs to be delivered to the intima to affect macrophage foam cell formation. In fact, the exposure of matricryptic sites within damaged ECM containing integrin recognition sites or SR-binding regions would be expected to cofacilitate uptake and removal of this debris. Interesting examples that are suggestive of overlapping binding affinities between these receptors are the findings that SR-A binds denatured collagen and mediates macrophage adhesion and that LOX-1 can mediate attachment of cells to fibronectin [28].

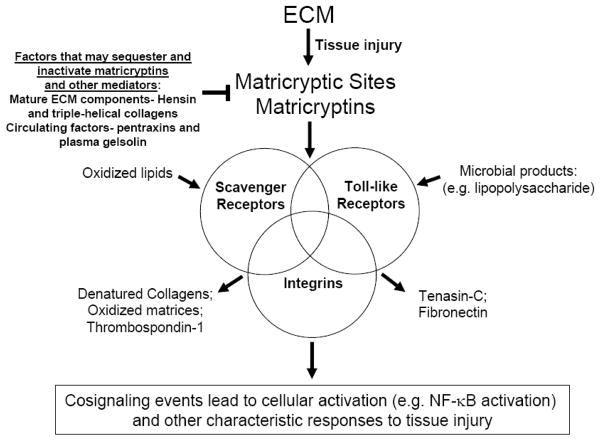

Past studies revealed that adhesion of macrophages to denatured collagens was mediated predominantly by SRs such as SR-A [28]. Many years ago, I showed that matricryptic RGD sites in denatured collagen type I promoted adhesion and integrin binding through integrin αvβ3 which only recognized denatured collagen and not native collagen [22]. This suggests that cells recognize denatured collagens through integrins and SRs (Figure 1). There has been little effort thus far to examine if these receptors work together to control recognition of matricryptic sites or to regulate unique signaling events that facilitate cellular recognition and responses to damaged molecules generated during tissue injury. Interestingly, recent work shows that endothelial cells express a SR, CL-P1, with affinity for oxidized LDL as well as polyanionic ligands such as polyinosinic acid and dextran sulfate [31]. It can also participate in uptake of both bacteria and yeast and possesses both the characteristic collagen-like binding domain but also a carbohydrate recognition domain (i.e. lectin). It will be important to determine if this SR participates with integrins in the recognition and response to matricryptic sites during cardiovascular injury responses independent of infectious diseases.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram indicating the possibility that matricryptic sites exposed in ECM following tissue injury may coactivate integrins in conjunction with the pattern recognition receptors including scavenger receptors and toll-like receptors. Different combinations of these receptors may cocluster to create unique signals that characterize responses to particular types of tissue injury. Select ligands are shown that interact uniquely with a particular class of receptor or which bind to at least two classes of receptor (arrows). Mature ECM such as triple-helical collagens and basement membrane matrices (e.g. hensin) may act to sequester matricryptins or other cell activating stimuli (such as oxidized LDL, lysophosphatidic acid or lipopolysaccharide) to suppress cell responses and decrease cell activation. This latter mechanism may function to maintain cell differentiation and cellular quiescence which is a characteristic of non-injured tissues.

One question of great interest is whether oxidized lipids such as oxidized LDL, when taken up into tissues, leads to oxidative modification or degradation of ECM components leading to exposure of matricryptic sites through liberation of matricryptins. Oxidized LDL is well known to adsorb to ECM so it is likely that local oxidation of ECM components will occur. In fact, recent studies show that there is marked oxidation of multiple ECM proteins when exposed to oxidized LDL (and this stimulates a humoral immune response) including fibronectin and collagens [32]. It is also described in past literature that oxidants degrade collagen molecules at proline residues, which are very abundant in collagens [33]. Thus, oxidation will generate collagen matricryptins containing RGD and other recognition sites to interact with integrins, SRs and possibly toll-like receptors (TLRs). In support of such concepts is the interesting finding that an extracellular superoxide dismutase (EC-SOD) exists which has strong binding affinity for triple-helical collagens in the ECM [33]. This suggests that this EC-SOD molecule is present to protect collagens from oxidant-induced cleavage [33].

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) were originally described as receptors for products of infectious agents such as lipids (i.e. lipopolysaccharide, lipotechoic acid), flagella, single and double-stranded RNA molecules, and CpG DNA from bacteria [3,34–36]. Particular TLRs have affinity for specific molecules but a common feature of these interacting molecules is that they possess repeating molecular structures. Repeating structures are found in many biological molecules such as nucleic acids, lipids, extracellular matrix molecules (i.e. collagens- Gly-X-Y; elastin; glycosaminoglycans with repeating disaccharide units) and cytoskeletal proteins (actin, tubulin, intermediate filaments). The term pattern recognition receptor was attributed to this class of receptors due to their ability to bind such repetitive molecular structures. Interestingly, the ECM is composed of molecules with repeating structures (e.g. domains) and units and thus, it is likely that ECM molecules might recognize such pattern recognition receptors. Fragments of hyaluronan (a glycosaminoglycan with repeating disaccharide units), but not intact or larger fragments, were identified as ligands for TLR-4, the receptor for lipopolysaccharide [3]. These fragments also promote cell migration and processes such as angiogenesis [3]. Furthermore, hyaluronic acid fragments were shown to be generated during pulmonary injury and TLR-4 was found to play a functional role in lung repair in a non-infectious disease [37]. This important finding suggests that TLR-4 and other TLRs play functional roles in diseases unrelated to infectious diseases and suggests that TLRs play signaling roles in a broader spectrum of responses to tissue injury. For example, TLR-4 has also recently been shown to play an important role in functional responses to myocardial ischemia [38]. This response may occur through recognition of matricryptic sites within fragmented ECM molecules from hyaluronic acid or other molecules. It is anticipated that multiple new ligands have yet to be discovered for TLRs or SRs including matricryptins derived from ECM with repeating units such as those derived from collagens, elastin, laminins, fibronectin, heparin, heparan and chondroitin sulfates. In support of this point, a newly published study shows that the ECM protein, tenascin-C, interacts with TLR-4 to affect inflammatory arthritis [39]. Also, previous work showed that an alternatively spliced segment (EDA) of fibronectin, which is induced in tissue injury responses, shows affinity for TLR-4 [40].

One of the key purposes of this review is to highlight the possibility that both TLRs and SRs are critical receptors for matricryptic sites and matricryptins from multiple ECM molecules and that new effort should be undertaken to identify such interactions and to investigate their functional relevance during tissue injury responses (Figure 1, Table 1). It makes considerable sense that matricryptic sites would be a key component of how cells and tissues recognize tissue injury since ECM directly surrounds cells and disruptions of its structure and function are known to profoundly affect tissue architecture and behavior. Furthermore, different types of tissue injury including those from ischemic, traumatic, or infectious causes are known to result in ECM damage (a common downstream consequence of tissue injury) which will lead to the exposure of matricryptic sites. I propose that select integrins, TLRs and SRs coassociate in different cell types to control responses to matricryptic sites and that these play a major role in how such cells respond to injury (Figure 1). This coassociation may allow for critical cell signaling cross-talk to control specific responses to particular types of tissue injury.

Table 1.

Key Experimental Directions for Future Work on Matricryptic Sites in Tissue Injury Responses

|

Considerable information now exists concerning how TLR-ligand interactions lead to downstream signal transduction [35]. A major transcription factor which is activated is NF-κB, in conjunction with activation of p38 MAP kinase and AP-1-dependent transcription. In comparison, many studies have shown that integrin ligation of αvβ3 and α5β1 integrins to RGD-containing ECM ligands strongly activates NF-κB [41]. Recent work investigating flow responsiveness and signaling in endothelial cells overlying atherosclerotic lesions reveal that ECM remodeling occurs involving fibronectin deposition which leads to marked activation of NF-κB [41]. These data suggest the possibility that TLR or SR activation is simultaneously occurring along with integrin recognition of matricryptic sites to affect NF-κB activation during cardiovascular injury responses.

Role of soluble pattern recognition receptors in regulating cardiovascular tissue injury as well as innate immunity responses

A very interesting series of soluble pattern recognition receptors are also known to control tissue injury responses and, in particular, control innate immunity responses (i.e. initial responses prior to the onset of humoral immunity) [42]. These include the acute phase reactants within plasma, C-reactive protein, serum amyloid P and the long pentraxin-3 (PTX-3) protein. Each of these molecules are members of the pentraxin family of molecules and are induced during tissue injury responses through the cytokines, tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1. These molecules have affinity for various components of microorganisms to play a role in innate immunity but also bind specific molecules such as C1q to affect complement activation as a part of this response [42]. Each of the pentraxins has a unique set of binding partners which affect their biologic spectrum of action. Interestingly, pentraxins show affinity for different ECM components [42] and, thus, in principle could bind to matricryptic sites to regulate their functions as well as affect the function of the ECM component to which the pentraxin binds. For example, recent work has shown that elevated plasma levels of C-reactive protein show strong correlations with increased cardiovascular risk for acute coronary vascular occlusive events. The mechanisms by which these pentraxins act to regulate tissue injury responses (positively or negatively) is ongoing but needs to be investigated in more detail in a number of directions including those related to how they affect cell signaling through ECM matricryptic sites.

Another interesting family of secreted pattern recognition receptors are the collectins [43], which are proteins with both a triple-helical collagenous domain but also a lectin domain with affinity for carbohydrates from endogenous proteins or from microorganisms such as fungi. Key members of this family include mannose-binding lectin (MBL) which is known to participate in innate immunity reactions to affect phagocytosis of multiple pathogens including bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites [44]. Of great interest is that MBL appears to play a key role in regulating the response to ischemia-perfusion injury in multiple organs including heart in a manner that is unrelated to complications via infection [44]. This suggests that MBL can play a major role in tissue injury responses independent of infectious disease and suggest the possibility of interactions with other non-infectious molecules such as matricryptic sites in damaged ECM that could mediate these effects. Several of the key surfactant proteins (SP-A and SP-D) in lung are collectins that again are thought to be key regulators of innate immunity by facilitating removal and phagocytosis of microorganisms inhaled into the lungs. Overall, what is fascinating about these proteins is that they possess triple-helical collagenous domains which provide them with the potential to bind unfolded or damaged proteins much like their related cell-surface expressed SRs.

The binding of collectins to such debris or microorganisms can facilitate uptake (through phagocytosis) via macrophages through integrins such as αMβ2, which incidently, can also bind to denatured and unfolded proteins. Interestingly, recent reports show that collectins, through their collagenous domain, also bind to the collagen-binding integrin, α2β1 [45]. Thus, it appears that collectins through their affinity for integrins can regulate signaling events that will affect responses during tissue injury events.

Recent reports describe another interesting triple-helix containing secreted protein, collagen triple helical repeat containing-1 (CTHRC-1), which is induced during vascular injury and appears to increase cell motility of vascular smooth muscle cells, decrease collagen synthesis and decrease TGF-beta-dependent signaling to influence vessel ECM remodeling following carotid artery ligation [46]. It is not homologous to the collectins, but contains a triple-helical domain collagenous domain that is sensitive to collagenase cleavage and is a homotrimeric molecule similar to the collectins and SRs. Thus, it is possible that this molecule also has the ability to serve as a soluble pattern recognition receptor through this collagenous region to influence vascular wall behavior following injury. It is also possible that this protein has affinity for α2β1 or other collagen-binding integrins to regulate integrin interactions with ECM during these injury responses. Another recent study suggests that CTHRC-1 can activate Wnt and planar cell polarity pathways [47] which further indicates that molecules such as these can mediate and affect critical signaling and morphogenic pathways.

Interesting role for circulating plasma gelsolin in controlling responses to acute mediators of tissue injury

The actin severing protein, gelsolin, is known to be expressed in two forms; an intracellular form which regulates calcium-dependent disassembly of F-actin to G-actin; and an extracellular, secreted form, which is thought to be released from the liver into the plasma to protect cells from actin polymers released from damaged and dying cells within the circulation and within damaged tissues. Of interest is the possibility that actin polymers might bind TLRs or SRs since actin polymers have the characteristics of other pattern recognition receptor ligands with repeating structures. Thus, plasma gelsolin could convert these polymers into actin monomers and possibly eliminate potential biological effects. Although there is currently no evidence for such an idea, it is compelling to think that released cytoskeletal components such as actin polymers, microtubules or intermediate filaments might be capable of activating TLRs or SRs. However, there is very interesting evidence that plasma gelsolin binds with high affinity and neutralizes the activities of lipopolysaccharide (from gram-negative bacteria) and lipotechoic acid (from gram-positive bacteria) so that TLRs such as TLR-4 and TLR-2 are not activated [48]. In addition, plasma gelsolin binds and can neutralize the activity of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), a key lipid mediator which activates cells during tissue injury responses. Furthermore, LPA is an important regulator of fibronectin matrix assembly during tissue injury in that it activates integrin-dependent interactions necessary to generate the mechanical forces required to reveal matricryptic sites that control fibronectin assembly. Interestingly, both fibronectin and plasma gelsolin are abundant plasma components which also interact with each other. Thus, circulating plasma gelsolin appears to be an important regulator of tissue injury responses and along with other circulating molecules, such as the pentraxins and collectins, can control such responses.

Is the mature extracellular matrix capable of binding cell-activating stimuli such as matricryptins, oxidized molecules, and microorganisms to facilitate cell quiescence and tissue stability?

As discussed above, some scavenger receptors as well as other pattern recognition receptors such as the collectins, have triple-helical collagenous domains with affinity for damaged molecules and polyanionic molecules. It is then of great interest to consider the possibility that abundant triple-helical collagen molecules within tissues may possess similar activities and could be involved in binding such molecules and competitively prevent their interactions with cells. Since the binding of matricryptins and molecules such as oxidized LDL activate cells, if surrounding stable matrices have affinity for such molecules, this could be one reason why mature ECM is a stabilizing and differentiating signal [19]. One function of collectins and/or molecules such as CTHRC-1 might be to competitively bind and displace such activating stimuli from the stable collagenous matrix to cells to facilitate activation and responses to injurious stimuli. Interestingly, in the study cited earlier regarding endothelial activation responses to flow, collagen and laminin coated substrates block activation, while fibronectin substrates strongly facilitate activation of NF-kappa B-dependent signaling mechanisms [41]. Thus, different ECM components may be capable of neutralizing or sequestering activating stimuli (e.g. matricryptins or oxidized LDL) to affect important cell behaviors. A final point here concerns some very interesting new data concerning the role of a basement membrane matrix protein expressed in epithelial cells, called DMBT1 or hensin, which supports these concepts. It was found that DMBT1 binds to polyanionic molecules and lipopolysaccharide, analogous to SR- and TLR-binding, and that this binding decreases responsiveness to such factors [49]. It is believed that this basement membrane protein decreases susceptibility to Crohn’s disease, an important inflammatory bowel disease, thus, suggesting that stable ECM structures surrounding cells may represent a key mechanism to maintain cell differentiation and decrease the local availability of cell activating stimuli which are upregulated following tissue injury.

Matricryptic site recognition and relevance of pattern recognition receptors in the pathogenesis of key cardiovascular diseases

The cardiovascular system reacts to diseases in many characteristic ways to control tissue injury responses such as those related to blood pressure control, hemorrhage, shock (septic and non-septic), edema and vascular permeability, atherosclerosis, and thrombosis. In each of these cases, there is evidence for the involvement for matricryptic sites, integrins and pattern recognition receptors in the molecular control of these disease processes. Initial work revealed that matricryptic collagen fragments and RGD peptides cause arteriole vasodilation through ligation of the αvβ3 integrin in vascular smooth muscle cells of the vascular wall [1,50]. Later, it was shown that ligation of the fibronectin receptor, α5β1, through interactions with the matricryptic RGD site of fibronectin leads to arteriolar vasoconstriction by activation of voltage gated L-type calcium channels in vascular smooth muscle [51]. In addition, it was shown that LDV peptides derived from the CS-1 alternatively spliced region of fibronectin promoted arteriolar vasoconstriction through the α4β1 integrin on vascular smooth muscle. Thus, multiple matricryptic sites with ECM molecules can affect a critical process such as arteriolar vasoconstriction to control blood flow to injured tissues. The ability to form a blood clot following endothelial cell denudation in tissue injury involves both fibrin and fibronectin matrix assembly and platelet adhesion to these matrices, processes that both critically dependent on the exposure of matricryptic sites to promote matrix assembly and platelet adhesion to integrin binding sites. This hemostatic process critically prevents hemorrhage, a major cause of lethality in humans following various types of injury. Recent work shows that platelet released thrombospondin-1 decreases hemorrhage following vascular injury through its ability to antagonize nitric oxide signaling in vascular smooth muscle and thus promote vasoconstriction to limit blood flow and prevent further hemorrhage [52]. Thus, there are many critical examples of how ECM and its matricryptic sites fundamentally regulate cardiovascular injury responses.

An important example illustrating the role of pattern recognition receptors in cardiovascular disease is our increasing understanding of how oxidized lipids such as those derived from oxidized LDL contribute to atherosclerosis [29,30,36]. The ability of multiple receptors (both membrane and soluble) within this family to bind these oxidized lipids is of great interest and has been linked to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Thus, innate immunity responses appear to be strongly activated during the atherosclerotic process despite the lack of an infectious etiology. As mentioned above, oxidized LDL is known to bind ECM with high affinity through heparan sulfate proteoglycans and other molecules and can contribute to oxidative modification of ECM, such as through modifications of fibronectin and collagens [32]. In some cases, this can eventually lead to immune-specific effects and the development of antibodies and cell-mediated immunity to oxidant modified molecules that are persistent within atheromatous plaques [30]. Thus, atherosclerotic lesions appear to stimulate multiple pathways including those affecting wound and tissue repair, innate immunity and specific immune responses to antigens.

In addition, a major cause of mortality in humans is shock which results from decreased blood pressure control caused by a number of pathogenic factors. Interestingly, lipopolysaccharide from gram-negative bacterial sepsis binds to TLR-4 and TLR-2 on cells such as vascular smooth muscle cells and causes significant vasodilation and loss of blood pressure. Another problem in this disease is that there are marked increases in vascular permeability that accompany this vasodilatory response via affects on endothelial cell junctional control of VE-cadherin based cell-cell contacts [53]. It is also of interest that TLR-4 can also be activated by matricryptic hyaluronan fragments to play a pathogenic a role in serious lung disease such as that follows during bleomycin-induced injury, which eventually leads to pulmonary fibrosis [3,37]. Recent work also shows that alterations in cardiac responses to myocardial infarction occur in TLR-4 knockout mice compared to controls [38]. The knockout animals showed comparable degrees of infarction in response to ischemia but showed reduced left ventricular remodeling and preserved systolic function compared to control animals. The mechanisms underlying these findings are unknown, but it is probable that matricryptic sites exposed in ECM following the cardiac injury and recognized by TLR-4 and its associated receptors is likely to play a pathogenic role.

Conclusion: Overlapping roles for integrins, scavenger receptors and toll-like receptors in recognition of damaged tissues and matricryptic sites in ECM to regulate responses to tissue injury

A major purpose of this review was to discuss topics that are typically not addressed together to consider the interesting possibility that exposure of ECM matricryptic sites is a fundamental part of a sensory and recognition system involving integrins, SRs and TLRs which control responses to diverse non-infectious and infectious tissue injuries (Figure 1, Table 1). Also, although SRs and TLRs are pattern recognition receptors that are typically considered as a fundamental component of innate immunity to invading microorganisms, much new work suggests that they also play a more general role in the recognition and response to non-infectious injuries. Furthermore, the ECM, like typical ligands for SRs and TLRs, contain repeating molecular structures which are known to be modified in all types of tissue injury. The exposure of matricryptic sites within ECM is now considered to be a critical feature controlling both ECM structure and function and these sites play fundamental roles in cell and tissue behaviors. Thus, I propose that exposure of matricryptic sites during various injurious events will engage overlapping pattern recognition receptors, both cell surface and soluble, that in conjunction with integrins will cooperatively control tissue injury responses. A Venn diagram is shown indicating that different combinations of these receptors may dictate the recognition and unique responses to particular injuries and that binding to matricryptic ECM sites could represent a critical signal dictating how cells respond to such injuries (Figure 1). It is not a coincidence that most pathogenic bacteria and fungi show specific affinity for particular ECM components (which may help them evade SR or TLR recognition) and furthermore, that in most infections there is evidence for matrix degradation and damage. Thus, there are direct parallels between non-infectious and infectious tissue injury and it is logical to think that a sensory and response system to identify and respond to such tissue injuries would include matricryptic ECM sites as a fundamental regulatory component.

Acknowledgments

GED is supported by grants HL59373, HL79460 and HL87308 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Davis GE, Bayless KJ, Davis MJ, Meininger GA. Regulation of tissue injury responses by the exposure of matricryptic sites within extracellular matrix molecules. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1489–1498. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65020-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maquart FX, Bellon G, Pasco S, Monboisse JC. Matrikines in the regulation of extracellular matrix degradation. Biochimie. 2005;87:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang D, Liang J, Noble PW. Hyaluronan in tissue injury and repair. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:435–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schenk S, Quaranta V. Tales from the crypt[ic] sites of the extracellular matrix. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:366–375. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tran KT, Lamb P, Deng JS. Matrikines and matricryptins: Implications for cutaneous cancers and skin repair. J Dermatol Sci. 2005;40:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adair-Kirk TL, Senior RM. Fragments of extracellular matrix as mediators of inflammation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1101–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J, Rodriguez D, Petitclerc E, Kim JJ, Hangai M, Moon YS, et al. Proteolytic exposure of a cryptic site within collagen type IV is required for angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:1069–1079. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gagne PJ, Tihonov N, Li X, Glaser J, Qiao J, Silberstein M, et al. Temporal exposure of cryptic collagen epitopes within ischemic muscle during hindlimb reperfusion. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1349–1359. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61222-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hocking DC, Kowalski K. A cryptic fragment from fibronectin’s III1 module localizes to lipid rafts and stimulates cell growth and contractility. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:175–184. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hocking DC, Titus PA, Sumagin R, Sarelius IH. Extracellular matrix fibronectin mechanically couples skeletal muscle contraction with local vasodilation. Circ Res. 2008;102:372–379. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith ML, Gourdon D, Little WC, Kubow KE, Eguiluz RA, Luna-Morris S, et al. Force-induced unfolding of fibronectin in the extracellular matrix of living cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vakonakis I, Staunton D, Rooney LM, Campbell ID. Interdomain association in fibronectin: insight into cryptic sites and fibrillogenesis. Embo J. 2007;26:2575–2583. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogel V. Mechanotransduction involving multimodular proteins: converting force into biochemical signals. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:459–488. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao M, Craig D, Lequin O, Campbell ID, Vogel V, Schulten K. Structure and functional significance of mechanically unfolded fibronectin type III1 intermediates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14784–14789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2334390100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitsi M, Forsten-Williams K, Gopalakrishnan M, Nugent MA. A catalytic role of heparin within the extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34796–34807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806692200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong C, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Brown J, Shaub A, Belkin AM, Burridge K. Rho-mediated contractility exposes a cryptic site in fibronectin and induces fibronectin matrix assembly. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:539–551. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.2.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi S, Leiss M, Moser M, Ohashi T, Kitao T, Heckmann D, et al. The RGD motif in fibronectin is essential for development but dispensable for fibril assembly. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:167–178. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huveneers S, Truong H, Fassler R, Sonnenberg A, Danen EH. Binding of soluble fibronectin to integrin alpha5 beta1 - link to focal adhesion redistribution and contractile shape. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2452–2462. doi: 10.1242/jcs.033001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis GE, Senger DR. Endothelial extracellular matrix: biosynthesis, remodeling, and functions during vascular morphogenesis and neovessel stabilization. Circ Res. 2005;97:1093–1107. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000191547.64391.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taooka Y, Chen J, Yednock T, Sheppard D. The integrin alpha9beta1 mediates adhesion to activated endothelial cells and transendothelial neutrophil migration through interaction with vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:413–420. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.2.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bayless KJ, Davis GE. Identification of dual alpha 4beta1 integrin binding sites within a 38 amino acid domain in the N-terminal thrombin fragment of human osteopontin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13483–13489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis GE. Affinity of integrins for damaged extracellular matrix: alpha v beta 3 binds to denatured collagen type I through RGD sites. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;182:1025–1031. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91834-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis GE. The Mac-1 and p150,95 beta 2 integrins bind denatured proteins to mediate leukocyte cell-substrate adhesion. Exp Cell Res. 1992;200:242–252. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90170-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Plow EF. Overlapping, but not identical, sites are involved in the recognition of C3bi, neutrophil inhibitory factor, and adhesive ligands by the alphaMbeta2 integrin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18211–18216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.18211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yalamanchili P, Lu C, Oxvig C, Springer TA. Folding and function of I domain-deleted Mac-1 and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21877–21882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908868199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Areschoug T, Gordon S. Scavenger receptors: role in innate immunity and microbial pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kodama T, Freeman M, Rohrer L, Zabrecky J, Matsudaira P, Krieger M. Type I macrophage scavenger receptor contains alpha-helical and collagen-like coiled coils. Nature. 1990;343:531–535. doi: 10.1038/343531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pluddemann A, Neyen C, Gordon S. Macrophage scavenger receptors and host-derived ligands. Methods. 2007;43:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hazen SL. Oxidized phospholipids as endogenous pattern recognition ligands in innate immunity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15527–15531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700054200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hartvigsen K, Chou MY, Hansen LF, Shaw PX, Tsimikas S, Binder CJ, et al. The role of innate immunity in atherogenesis. J Lipid Res. 2009;50 (Suppl):S388–393. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800100-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jang S, Ohtani K, Fukuoh A, Yoshizaki T, Fukuda M, Motomura W, et al. Scavenger receptor collectin placenta 1 (CL-P1) predominantly mediates zymosan phagocytosis by human vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3956–3965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807477200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duner P, To F, Alm R, Goncalves I, Fredrikson GN, Hedblad B, et al. Immune responses against fibronectin modified by lipoprotein oxidation and their association with cardiovascular disease. J Intern Med. 2009;265:593–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersen SV, Oury TD, Ostergaard L, Valnickova Z, Wegrzyn J, Thogersen IB, et al. Extracellular superoxide dismutase (EC-SOD) binds to type i collagen and protects against oxidative fragmentation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13705–13710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kluwe J, Mencin A, Schwabe RF. Toll-like receptors, wound healing, and carcinogenesis. J Mol Med. 2009;87:125–138. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0426-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee MS, Kim YJ. Signaling pathways downstream of pattern-recognition receptors and their cross talk. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:447–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060605.122847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curtiss LK, Tobias PS. Emerging role of Toll-like receptors in atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2009;50 (Suppl):S340–345. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800056-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang D, Liang J, Fan J, Yu S, Chen S, Luo Y, et al. Regulation of lung injury and repair by Toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nat Med. 2005;11:1173–1179. doi: 10.1038/nm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Timmers L, Sluijter JP, van Keulen JK, Hoefer IE, Nederhoff MG, Goumans MJ, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates maladaptive left ventricular remodeling and impairs cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2008;102:257–264. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Midwood K, Sacre S, Piccinini AM, Inglis J, Trebaul A, Chan E, et al. Tenascin-C is an endogenous activator of Toll-like receptor 4 that is essential for maintaining inflammation in arthritic joint disease. Nat Med. 2009;15:774–780. doi: 10.1038/nm.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okamura Y, Watari M, Jerud ES, Young DW, Ishizaka ST, Rose J, et al. The extra domain A of fibronectin activates Toll-like receptor 4. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10229–10233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orr AW, Sanders JM, Bevard M, Coleman E, Sarembock IJ, Schwartz MA. The subendothelial extracellular matrix modulates NF-kappaB activation by flow: a potential role in atherosclerosis. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:191–202. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bottazzi B, Garlanda C, Salvatori G, Jeannin P, Manfredi A, Mantovani A. Pentraxins as a key component of innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta G, Surolia A. Collectins: sentinels of innate immunity. Bioessays. 2007;29:452–464. doi: 10.1002/bies.20573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takahashi K, Ip WE, Michelow IC, Ezekowitz RA. The mannose-binding lectin: a prototypic pattern recognition molecule. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zutter MM, Edelson BT. The alpha2beta1 integrin: a novel collectin/C1q receptor. Immunobiology. 2007;212:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.LeClair R, Lindner V. The role of collagen triple helix repeat containing 1 in injured arteries, collagen expression, and transforming growth factor beta signaling. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2007;17:202–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamamoto S, Nishimura O, Misaki K, Nishita M, Minami Y, Yonemura S, et al. Cthrc1 selectively activates the planar cell polarity pathway of Wnt signaling by stabilizing the Wnt-receptor complex. Dev Cell. 2008;15:23–36. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bucki R, Byfield FJ, Kulakowska A, McCormick ME, Drozdowski W, Namiot Z, et al. Extracellular gelsolin binds lipoteichoic acid and modulates cellular response to proinflammatory bacterial wall components. J Immunol. 2008;181:4936–4944. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.End C, Bikker F, Renner M, Bergmann G, Lyer S, Blaich S, et al. DMBT1 functions as pattern-recognition molecule for poly-sulfated and poly-phosphorylated ligands. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:833–842. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mogford JE, Davis GE, Platts SH, Meininger GA. Vascular smooth muscle alpha v beta 3 integrin mediates arteriolar vasodilation in response to RGD peptides. Circ Res. 1996;79:821–826. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.4.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu X, Mogford JE, Platts SH, Davis GE, Meininger GA, Davis MJ. Modulation of calcium current in arteriolar smooth muscle by alphav beta3 and alpha5 beta1 integrin ligands. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:241–252. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.1.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Isenberg JS, Frazier WA, Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1: a physiological regulator of nitric oxide signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:728–742. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7488-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vandenbroucke E, Mehta D, Minshall R, Malik AB. Regulation of endothelial junctional permeability. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1123:134–145. doi: 10.1196/annals.1420.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]