Abstract

Several methods have been proposed for motion correction of High Angular Resolution Diffusion Imaging (HARDI) data. There have been few comparisons of these methods, partly due to a lack of quantitative metrics of performance. We compare two motion correction strategies using two figures of merit: displacement introduced by the motion correction and the 95% confidence interval of the cone of uncertainty of voxels with prolate tensors. What follows is a general approach for assessing motion correction of HARDI data that may have broad application for quality assurance and optimization of postprocessing protocols. Our analysis demonstrates two important issues related to motion correction of HARDI data: 1) although neither method we tested was dramatically superior in performance, both were dramatically better than performing no motion correction, and 2) iteration of motion correction can improve the final results. Based on the results demonstrated here, iterative motion correction is strongly recommended for HARDI acquisitions.

1. Introduction

Motion artifact is a long-standing problem for MRI for which a number of prospective and retrospective correction strategies have been implemented [1]. Motion correction of High Angular Resolution Diffusion Imaging (HARDI) [2] is absolutely necessary because substantial vibrations [3] from diffusion-weighting gradients and long scan duration result in head movement comparable to or larger than the voxel size. However, as each image volume in a HARDI acquisition exhibits different image contrast due to differences in diffusion weighting, standard motion correction strategies may not work.

As testament to the difficulty of the problem, only a handful of motion correction strategies have been published, and quantitative assessment of the quality of the motion correction is not extensive. Andersson and Skare [4] optimize eddy current distortion and motion correction parameters by minimizing the residual to the tensor fit. However, no quantitative assessment of the quality of the motion correction, besides minimization of the residual, is presented. Rohde et al. [5] use a normalized mutual information cost function to optimize overlap between T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted images. To assess the quality of the motion correction, variance of higher-order principal components is shown to be lower after motion correction. Unfortunately, it is unclear how much of the variance may be due to motion or from contrast variations inherent to diffusion-weighting. Bai and Alexander [6] fit the non-motion corrected data to the tensor model. Then, for each image volume in the original data set, a reference image volume is generated from the tensor fit. Each image volume is then motion-corrected separately using its corresponding reference. Principal eigenvectors generated from four subsets of the diffusion-weighted images are shown to be more collinear after motion correction. However, the statistics are limited by the small number of subsets.

In this contribution, a general approach for assessing the quality of motion correction for HARDI acquisitions is proposed. Two motion correction strategies, implemented with widely available, free FSL software (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) [7] are assessed using two metrics. The first is the displacement of each image volume [8]. Displacement is defined as the mean, among selected voxels in the image volume, movement imposed by the motion correction algorithm. If the motion correction is stable, the maximum displacement, among image volumes, should approach an asymptotic value when the motion correction is iterated. If the motion correction is effective, the asymptotic value should be small as compared to the voxel size. Displacement was first introduced to assess motion of BOLD-fMRI acquisitions but has not, to our knowledge, been applied to HARDI acquisitions.

The other quality metric is the 95% confidence interval of the cone of uncertainty of the principal eigenvector of the diffusion tensor (CU95) [9, 10]. We assume that, in regions of highly organized white matter, more successful motion correction will lead to a smaller value of CU95. The cone of uncertainty is generated using noise realizations generated by the wild bootstrap method [11], which requires no additional special acquisitions for its implementation, and can therefore be applied to any existing HARDI data set. Comparisons of two motion correction protocols are performed using displacement and CU95.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Image acquisition

Sixty-two (62) subjects were imaged under a Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board-approved protocol. Of the subjects, 35 were multiple sclerosis patients exhibiting varying degrees of atrophy and white matter lesions (9M / 26F, age = 43.9 ± 9.2 years ranging from 29–50 years), 27 were controls exhibiting no signs of neurological disease (9M / 18F, age = 41.0 ± 15.4 years ranging from 28–59 years), and two subjects were epilepsy patients (2F, Ages 52 and 54). All images were acquired on a Siemens 3T TIM Trio (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). A twice-refocused spin echo [12] with single-shot EPI readout (FOV = 256 × 256 mm, 128 × 128 matrix, 5/8 partial fourier factor, 48 slices 2mm thick, TE/TR = 92/7700 msec, isotropic voxels 2mm on a side) was used to acquire 71 diffusion-weighted image volumes, b-value of 1000 sec/mm2, with diffusion gradients selected by a coulomb repulsion algorithm [13] and eight T2-weighted volumes with b-value of 0 sec/mm2. Four averages were acquired for each subject for a total scan time of 41 minutes.

2.2 Motion correction

Two motion-correction protocols were implemented using the MCFLIRT tool of FSL [14]. The strategies differ by their use of different reference images. The first, T2-reference, approach follows that of Rohde et al. [5] in its use of normalized mutual information as a cost function for comparing images with different contrast. MCFLIRT is applied to all T2-weighted image volumes (i.e. acquired with b = 0 sec/mm2) using default options only (6 degrees of freedom, normalized correlation cost function, reference volume is number 16 of 32), and iterated 20 times. Diffusion-weighted images are then processed with MCFLIRT, using the mean T2-weighted image as the reference image, normalized mutual information as the cost function, and iterated 20 times. The number of degrees of freedom was set to 6: 3 translations and 3 rotations. More degrees of freedom, accounting for shear and scaling, can be used in cases when the acquisition suffers from eddy current distortion. However, the twice-refocused spin echo rendered eddy-current distortions negligible, as was verified by subtracting images acquired with different diffusion gradient orientations on a spherical agar phantom, and the absence of systematic ring-shaped artifact on the perimeter of the phantom indicated effective elimination of distortions minimized such artifacts.

The second, tensor-reference, approach follows that of Bai and Alexander [6]. The image data is fit to the diffusion tensor using a log-linear fit [15], and the tensor fit is then used to synthesize a different reference image volume corresponding to each of the acquired image volumes. Each pair of acquired and reference images then exhibit similar contrast properties, within the limits of the tensor model. Each acquired image volume is then subject to MCFLIRT, using the corresponding tensor-derived image as a reference. The process is iterated 20 times. The number of degrees of freedom was set to 6 and normalized correlation was the cost function. Although the original work of Bai and Alexander used normalized mutual information as the cost function, we used normalized correlation, as it is more appropriate for images with similar contrast [16].

Diffusion gradient vectors were updated to incorporate rotations due to motion correction [17, 18]. Each iteration of motion correction introduces errors due to image interpolation. To minimize such errors, the affine transformation matrices from each iteration were multiplied and then applied to the original data so that interpolation was performed only once on the data used for the cone of uncertainty analysis.

2.3 Displacement and Cone of Uncertainty Analysis

For both T2-reference and tensor-reference methods, the image displacement imposed by the motion correction was calculated for each image volume after each iteration [8]. MCFLIRT provides the affine transformation matrix for each image volume after each iteration of motion correction. The mean displacement is readily calculated by applying the affine matrix to a subset of voxels in the image volume and taking the mean magnitude of the vector difference of the positions of the voxels before and after the matrix multiplication. For each iteration, the maximum, among image volumes, displacement was used for further analysis. A reasonable requirement for adequate motion correction is for the displacement to fall below a threshold of half the geometric mean of the voxel dimensions after iteration. In this particular study, the threshold is 1.0mm.

For each motion correction approach, the wild bootstrap method [11] was used to generate 1000 noise realizations for each voxel of the motion-corrected data. The tensor and its principal eigenvector were calculated for each noise realization. The 95% confidence interval of the cone of uncertainty (CU95) of principal eigenvectors was then calculated taking the 95th percentile value [9, 10]. We assume that the more effective motion correction strategy should result in smaller CU95 in regions of highly organized white matter.

Statistical comparison was performed by paired t-test of CU95 of corresponding voxels with prolate (cigar-shaped) tensors. Prolate tensors are used as a proxy for selection of highly organized white matter and were selected using quantitative shape measures introduced by Westin et al. [19]: Clinear > Cplanar, Cspherical. It has been shown that voxels with low values of Clinear, corresponding to oblate (pancake-shaped) tensors, exhibit high variances in CU95 [10]. The high variances associated with oblate tensors may mask variability due to motion while the high spread of variances among oblate tensors with low values of Clinear would require additional measures of variance of CU95.

Corresponding voxels were selected as follows. First, T2-weighted images derived from T2-reference and tensor-reference data were coregistered using the FLIRT program from FSL [16]. This step is necessary since the different motion correction methods can result in a slightly different final orientation of the data. Coregistration parameters were then used to transform tensor-reference derived prolate tensor masks and CU95 maps to the reference frame of the T2-reference images. After transformation, there is a pair of prolate tensor masks and a pair of CU95 maps, with one member of each pair being derived from T2-weighted images and the other member transformed from tensor-reference derived data. The arithmetic difference between the CU95 maps was taken within voxels occupied in both prolate tensor masks. A similar process was performed using maps generated directly from tensor-reference data and from transformed T2-reference data. The entire procedure was repeated for each subject’s data. A one-sample t-test was then performed on the CU95 difference from voxels representing prolate tensors from all studies. As the one-sample t-test is performed on the arithmetic difference in CU95 values, this is equivalent to a paired t-test.

2.4 Assessment of Bias Among Tensor Properties

Images from HARDI datasets are rarely examined directly. Of greater interest are properties of the diffusion tensor [15] which can be used as surrogate measures of tissue integrity [20, 21]. To assess bias in tensor properties introduced by motion, a voxel-by-voxel comparison of fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), longitudinal diffusivity (LD, the largest eigenvalue), and transverse diffusivity (TD, the mean of the smallest two eigenvalues) was performed as follows. The mean T2-weighted images of non-motion corrected were coregistered to the mean T2-weighted images of the tensor-reference and the T2-reference motion-corrected data. Coregistration parameters were then used to transform FA, MD, LD, and TD maps to the same space. The arithmetic difference between parameters at each voxel among all studies was subject to a one-sample t-test. As the one-sample t-test is performed on a difference, it is equivalent to a paired t-test, and the sign of the mean difference indicates the direction of the bias if there is a statistically significant difference. Only voxels that were in tissue in both non-motion corrected and motion-corrected data were considered.

3. Results

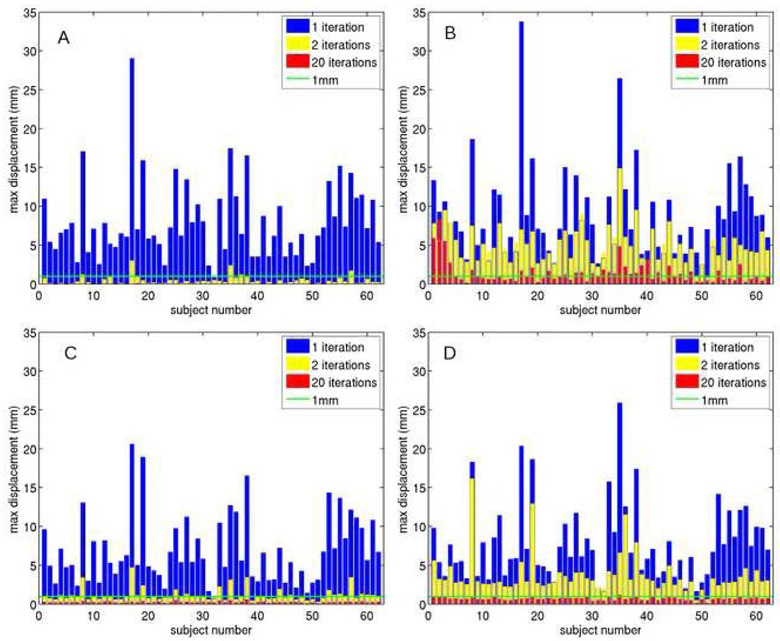

An important result of this study is the importance of iterating the motion correction. Figure 1 shows, for each subject, the maximum displacement, among image volumes, for the first, second, and final iteration. Results for T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted images are shown separately. For the T2-weighted images in the T2-reference approach (figure 1A), maximum displacement drops rapidly with iteration and falls below 1 mm for all subjects after final iteration. However, the diffusion-weighted images of the T2-reference approach (figure 1B) show only a moderate reduction of maximum displacement upon the second iteration. Only 34 of 62 subjects’ data show maximum displacement of less than 1mm after 20 iterations. For the tensor-reference approach, all T2-weighted datasets show displacements of less than 1 mm after 20 iterations and nearly all (58 of 62) diffusion-weighted datasets show displacements of less than 1 mm after 20 iterations. Thus, using the maximum displacement as a measure of motion correction efficacy, the tensor-fit method appears to converge more reliably to a minimum after 20 iterations than the T2-reference method.

Figure 1.

Maximum, among image volumes, displacement after first, second, and final iteration of motion correction, for each subject, for (A) T2-weighted images, T2-reference method, (B) diffusion-weighted images, T2-reference method, (C) T2-weighted images, tensor-reference method, (D) diffusion-weighted images, tensor-reference method. A line indicating 1mm displacement is shown as a guide to the eye.

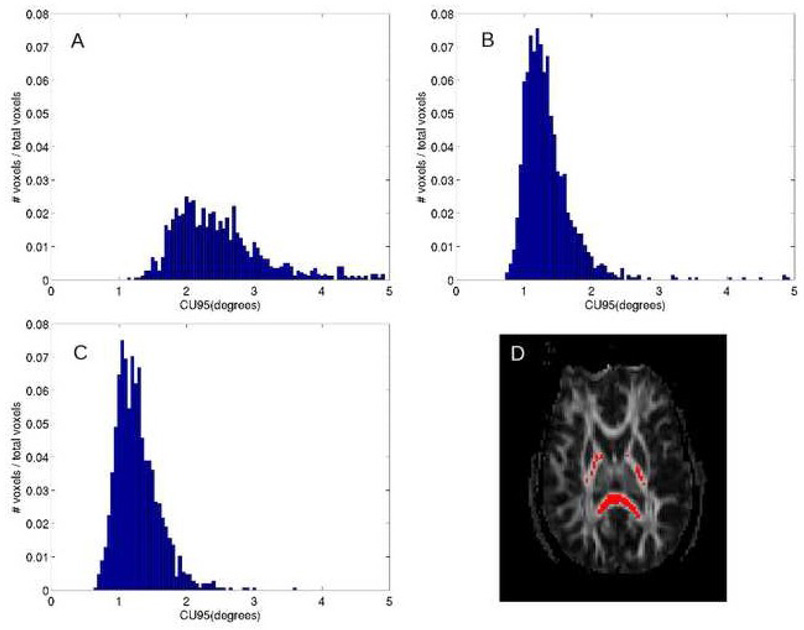

To illustrate the impact of motion correction, figure 2 shows histograms, normalized to unit area, of cone of uncertainty in voxels with prolate tensors for one subject. Voxels corresponding to prolate tensors are highlighted in red on a FA map to illustrate their location in highly organized white matter regions, such as splenium and posterior limb of the internal capsule. The number of voxels represented in each histogram is slightly different (1035 voxels for the no motion correction case and 1362 voxels for the T2-reference and tensor-fit cases), as the motion correction has an impact on the calculated values of shape measures, Clinear, Cplanar, and Cspherical. CU95 is clearly smaller for the motion-corrected cases, than for the non-motion corrected case, but the differences between the two types of motion correction are more subtle. The paired t-test comparison of cone of uncertainty shows a slight but significant difference (p < 0.000001), with the CU95 of the tensor-reference among 158778 pairwise voxel comparisons, being smaller than that of the CU95 of the T2-reference data by a mean value of 0.82 degrees. As with the displacement analysis, the cone of uncertainty analysis indicates that the tensor-reference method performs better for this dataset.

Figure 2.

Normalized histograms of 95% confidence interval of the cone of uncertainty in voxels with prolate tensors for (A) no motion correction, (B) T2-reference motion correction, and (C) tensor-reference motion correction. (D) FA map with voxels containing prolate tensors from tensor-reference motion correction data.

Table 1 summarizes the results of the assessment of bias among tensor properties. The mean difference among all voxels and 95% confidence intervals are given. FA and LD tend to be lower when derived from non-motion-corrected data than from motion-corrected data while MD and TD tend to be higher. All differences were significant (p < 0.00001).

Table 1.

Mean Difference of Parameters Derived from Non- and Motion-Corrected Data

| Parameter | T2-reference | Tensor-reference |

|---|---|---|

| FA a | −19.58 b ± 0.05 c | −19.58 ± 0.05 |

| MD d | 23.6 ± 0.1 | 24.1 ± 0.1 |

| LD | −24.9 ± 0.2 | −23.6 ± 0.2 |

| TD | 48.2 ± 0.1 | 48.3 ± 0.1 |

Scaled by 1000

Mean of (Parameter from Motion-Corrected Data) – (Parameter from Non-Motion-Corrected Data)

95% Confidence Interval

MD, LD, TD in units of mm2/sec

4. Discussion

Displacement and cone of uncertainty are broadly applicable, quantitative metrics that can be used to compare and monitor the performance of motion correction protocols. Specific details of the data acquisition or motion correction protocol may vary among situations, but the same metrics can still be used. For example, in acquisitions exhibiting large eddy current artifact, MCFLIRT using 12 degrees of freedom (3 degrees of freedom each for translation, rotation, shear, and scaling) for the entire volume could be compared to the method proposed by Andersson and Skare [4], which accounts for spatial variation of eddy currents. As another example, in a single study (data not shown) with high spatial resolution but low signal-to-noise ratio, the metrics indicated qualitatively better performance for the T2-reference method than for the tensor-reference method.

Furthermore, these metrics can be used to compare the efficacy of motion correction for different acquisition schemes. For example, it has been demonstrated that CSF suppression can improve the accuracy of correlation-type methods for comparison of T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted images [22, 23]. It would in principle be straightforward to perform a quantitative comparison of motion correction using CSF-suppressed images as a reference as opposed to a T2-weighted image.

The assessment of bias suggests that tensor properties are modified significantly by motion correction. For this dataset, FA and LD are biased high while MD and TD are biased low if there is no motion correction. These results basically concur with trends in tensor properties in response to random noise [24] if one assumes that absence of motion correction corresponds to higher noise levels. However, it is difficult to draw general conclusions about the impact of motion on tensor properties, as the degree and trajectory of motion may vary widely from scan to scan, although reasonable attempts at modeling the effects of motion on tensor properties have been made [18, 25].

The impact of motion correction on tractography [26] would be of great interest. Assessment of the accuracy of tractography requires comparison with anatomical gold standard measurements, which are not readily accessible. However, it may be possible to implement parameterizations of tracts such as those introduced by Clayden et al. [27] and Batchelor et al. [28] to determine the impact of motion on tract variability and may be the subject of future investigation. Without such quantitative metrics of tract properties, any assessment of the impact of motion on tractography is highly susceptible to operator-related bias.

The comparison of cone of uncertainty metrics may also be subject to improvement. The approach taken here was to use a simple percentile, as proposed by Jones [10], but it has been shown that anisotropy in the cone of uncertainty may affect its statistics [29, 30]. The impact of such anisotropy may affect specific decisions regarding a given dataset or datasets, but the cone of uncertainty would still serve as a valid metric for assessing motion correction. Furthermore, comparison was confined to voxels with prolate tensors, a small minority. Inspection of CU95 maps suggests that motion correction reduces CU95 in other voxels as well. However, the variance in CU95 increases dramatically as Clinear drops below ~0.15 [10], so statistical comparisons would require an independent measure of variance as a function of Clinear.

The number of gradient directions may also influence the metrics. For example, consider a scenario in which one of 300 HARDI acquisitions is corrupted by a transient artifact, such as a gradient spike. This single image may exhibit large displacement regardless of the number of iterations. However, the contribution to the tensor fit from this one image will be small because of the large number of other, uncorrupted images, and so the cone of uncertainty may not appear abnormally large. In a more limited dataset, such as a minimal 7-direction acquisition often used for diffusion tensor imaging, the impact on the cone of uncertainty would be more noticeable.

The overall duration of the imaging session will have a strong impact on the degree of motion examined. The studies examined here are long compared to many studies, with 41 minutes dedicated to the HARDI acquisition alone. The duration of the scan was chosen in order to achieve adequate signal to noise ratio for the voxel dimensions. Shorter scans will be less prone, but not immune to, motion. For short scans, it may be desirable to use displacement as a quality control measure to exclude images exhibiting unacceptably large amounts of displacement.

So far as the iterative approach to motion correction is concerned, a number of reasonable modifications can be made. For the sake of comparison, 20 iterations were applied to all datasets. In practice, however, the iteration process may be terminated when the maximum displacement is less than some reasonable threshold, such as half the geometric mean of the voxel dimensions, thereby reducing postprocessing time. Also, if isolated image volumes demonstrate large amounts of displacement that cannot be reduced by iteration, they could be excluded from analysis in a fashion analogous to the RESTORE method proposed by Chang et al. [31] and as implemented in part of the work by Bai and Alexander [6].

5. Conclusion

We introduce a general approach for quantitative assessment of motion correction of HARDI data. The motion correction schemes examined here use readily available, free software (FSL [7]). For the data examined here, the tensor-fit scheme performs better with regard to displacement and cone of uncertainty. For this dataset, then, we would then prefer the tensor-fit scheme. Generally speaking, motion correction algorithm performance will likely depend on a number of factors, such as signal to noise ratio, number of diffusion directions, and absolute amount of motion. We strongly recommend that researchers evaluate motion correction using the presented methods if their acquisition differs considerably from the one we present here.

The assessment methodology can be applied to any postprocessing motion correction scheme, such as those of Rohde et al. [5] and Andersson and Skare [4]. Furthermore, the amount of displacement and the distribution of cone of uncertainty can be used as quality control measures; data exhibiting unusually high levels of displacement or cone of uncertainty can be excluded from consideration on objective grounds. Finally, the approach requires no special acquisitions and so can be applied to data from any HARDI acquisition.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (grant RG 3751-B-2) and the NIH (R21 NS059571-01A2) and assistance in data acquisition and analysis from Jian Lin, Derrek Tew, John Cowan, and Katherine Murphy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Carroll TJ, Sakaie KE, Wielopolski PA, Edelman RR. Advanced Imaging Techniques, Including Fast Imaging. In: Edelman RR, Hesselink JR, Zlatkin MB, Crues JV, editors. Clinical Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. pp. 187–230. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuch DS, Reese TG, Wiegell MR, Makris N, Belliveau JW, Wedeen VJ. High angular resolution diffusion imaging reveals intravoxel white matter fiber heterogeneity. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:577–582. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hiltunen J, Hari R, Jousmaki V, Muller K, Sepponen R, Joensuu R. Quantification of mechanical vibration during diffusion tensor imaging at 3 T. Neuroimage. 2006;32:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson JL, Skare S. A model-based method for retrospective correction of geometric distortions in diffusion-weighted EPI. Neuroimage. 2002;16:177–199. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rohde GK, Barnett AS, Basser PJ, Marenco S, Pierpaoli C. Comprehensive approach for correction of motion and distortion in diffusion-weighted MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:103–114. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bai Y, Alexander DC. Model-Based Registration to Correct for Motion Between Acquistions in Diffusion MR Imaging; The Fifth IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging, Vol. 5. Paris IEEE; 2008. p. 1784. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23 Suppl 1:S208–S219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang AP, Kennedy DN, Baker JR, Weisskoff RM, Tootell RBH, Woods RP, Benson RR, Kwong KK, Brady TJ, Rosen BR, Belliveau JW. Motion detection and correction in functional MR imaging. Human Brain Mapping. 1995;3:224–235. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basser PJ, Pajevic S. Statistical artifacts in diffusion tensor MRI (DT-MRI) caused by background noise. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:41–50. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200007)44:1<41::aid-mrm8>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones DK. Determining and visualizing uncertainty in estimates of fiber orientation from diffusion tensor MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:7–12. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitcher B, Tuch DS, Wisco JJ, Sorensen AG, Wang L. Using the wild bootstrap to quantify uncertainty in diffusion tensor imaging. Hum Brain Mapp. 2008;29:346–362. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reese TG, Heid O, Weisskoff RM, Wedeen VJ. Reduction of eddy-current-induced distortion in diffusion MRI using a twice-refocused spin echo. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:177–182. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones DK, Horsfield MA, Simmons A. Optimal strategies for measuring diffusion in anisotropic systems by magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:515–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17:825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basser PJ, Mattiello J, LeBihan D. Estimation of the effective self-diffusion tensor from the NMR spin echo. J Magn Reson B. 1994;103:247–254. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1994.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5:143–156. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farrell JA, Landman BA, Jones CK, Smith SA, Prince JL, van Zijl PC, Mori S. Effects of signal-to-noise ratio on the accuracy and reproducibility of diffusion tensor imaging-derived fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, and principal eigenvector measurements at 1.5 T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26:756–767. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leemans A, Jones DK. The B-matrix must be rotated when correcting for subject motion in DTI data. Magn Reson Med. 2009 doi: 10.1002/mrm.21890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westin CF, Maier SE, Mamata H, Nabavi A, Jolesz FA, Kikinis R. Processing and visualization for diffusion tensor MRI. Med Image Anal. 2002;6:93–108. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(02)00053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horsfield MA, Jones DK. Applications of diffusion-weighted and diffusion tensor MRI to white matter diseases - a review. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:570–577. doi: 10.1002/nbm.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Assaf Y, Pasternak O. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)-based white matter mapping in brain research: a review. J Mol Neurosci. 2008;34:51–61. doi: 10.1007/s12031-007-0029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bastin ME. On the use of the FLAIR technique to improve the correction of eddy current induced artefacts in MR diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;19:937–950. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(01)00427-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Crespigny AJ, Moseley ME. Eddy Current Induced Image Warping in Diffusion Weighted EPI; Proceedings 6th Scientifice Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Vol Sydney; 1998. p. 661. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pierpaoli C, Basser PJ. Toward a quantitative assessment of diffusion anisotropy. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:893–906. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tijssen RH, Jansen JF, Backes WH. Assessing and minimizing the effects of noise and motion in clinical DTI at 3 T. Hum Brain Mapp. 2008 doi: 10.1002/hbm.20695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mori S, Crain BJ, Chacko VP, van Zijl PC. Three-dimensional tracking of axonal projections in the brain by magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:265–269. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199902)45:2<265::aid-ana21>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clayden JD, Bastin ME, Storkey AJ. Improved segmentation reproducibility in group tractography using a quantitative tract similarity measure. Neuroimage. 2006;33:482–492. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batchelor PG, Calamante F, Tournier JD, Atkinson D, Hill DL, Connelly A. Quantification of the shape of fiber tracts. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:894–903. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeong H-K, Lu Y, Ding Z, Anderson AW. Characeterizing the cone of uncertainty in diffusion tensor MRI; Proceedings of the 13th Scientific Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Vol 13. Miami; 2005. p. 1317. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koay CG, Nevo U, Chang LC, Pierpaoli C, Basser PJ. The elliptical cone of uncertainty and its normalized measures in diffusion tensor imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2008;27:834–846. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2008.915663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang LC, Jones DK, Pierpaoli C. RESTORE: robust estimation of tensors by outlier rejection. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:1088–1095. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]