Abstract

Using the fluorescent amino acid tryptophan (Trp), we have characterized the copper(II) binding of F4W α-synuclein in the presence and absence of dioxygen at neutral pH. Variations in Trp fluorescence indicate that copper(II) binding is enhanced by the presence of dioxygen, with the apparent dissociation constant (Kd(app)) changing from 100 nM (anaerobic) to 10 nM (aerobic). To investigate the possible role of methionine oxidation, complementary work focused on synthetic peptide models of the N-terminal Cu(II)-α-syn site, MDV(F/W) and M*DV(F/W), where M*= methionine sulfoxide. Furthermore, we employed circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to demonstrate that the phenyl-to-indole (F→W) substitution does not alter copper(II) binding properties and to confirm the 1:1 metal-peptide binding stoichiometry. CD comparisons also revealed that Met1 oxidation does not affect the copper-peptide conformation and further suggested the possible existence of a CuII-Trp/Phe (cation-π) interaction.

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, amyloid, tryptophan, circular dichroism, methionine oxidation, cation-π

1. Introduction

The study of copper interactions with amyloidogenic proteins such as amyloid β (Aβ), prion, and α-synuclein (α-syn) in the context of neurodegenerative diseases is a rapidly progressing field of research within the biochemical and neurological science communities [1-4]. Altered copper homeostasis is the likely source of copper ions, however their specific mechanistic role has yet to be determined. Protein misfolding and aggregation as a result of elevated oxidative stress is thought to be promoted by copper-catalyzed protein oxidation, reaction of endogenous copper species with dioxygen (O2), or copper-induced generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [5, 6].

The presynaptic protein α-syn, found in intracellular fibrillar (amyloid) deposits of Parkinson's disease (PD) victims, recently has been connected to copper(II) chemistry [7]. In particular, copper(II) ions have been shown to accelerate fibril formation, a process that has been implicated in the PD pathogenic mechanism [8]. Furthermore, cell culture assays suggest that aggregates formed in the presence of copper(II) are more cytotoxic than those that form from protein alone [9]. Although soluble monomeric α-syn is believed to be significantly less neurotoxic than the fibrillar or oligomeric forms [10], an understanding of how copper(II) interacts with the natively unfolded protein is necessary before a mechanism of copper initiated fibril formation can be addressed.

The primary amino acid sequence of α-syn can be categorized into three main regions: the N-terminal region containing 5 of 7 imperfect amphipathic repeats (1-60), the non-amyloid β component (NAC) region (61-95), and a highly acidic (15 carboxylates) C-terminus (96-140) (Scheme 1). Due to the intrinsically disordered nature of α-syn, CuII-stimulated protein aggregation is particularly intriguing. The binding of metal ions can either perturb protein conformation and thereby alter function, or the metal-protein complex can directly participate in the production of ROS, or both mechanisms could be at work.

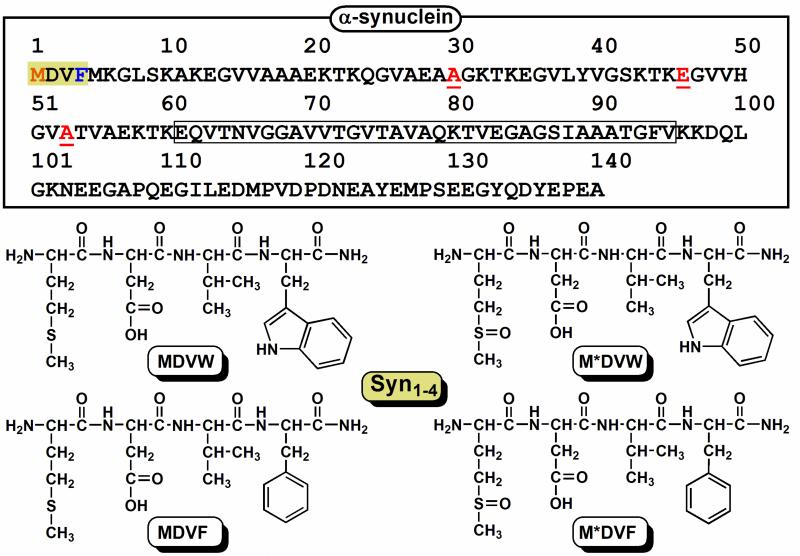

Scheme 1.

Top: The primary amino acid sequence of human α-synuclein is illustrated with the first four N-terminal residues shaded, i.e. the primary copper(II) binding site. The non-amyloid β component (NAC) region is boxed and the three residues associated with early-onset PD mutations are underlined. Bottom: A schematic of all Syn1-4 Trp-containing peptides, MDV(W/F) and M*DV(W/F) (M*= methionine sulfoxide), is illustrated.

Copper(II) has been shown to bind with varied dissociation constants (nM to mM) within all three α-syn regions by a variety of techniques under numerous solution conditions [11-15]. In our own work, we found that a Trp-containing α-syn variant (F4W) is the most responsive CuII reporter [16] and subsequently, using synthetic peptides we identified the minimal N-terminal binding site to be within the first four residues, MDVF (Syn1-4) [17]. In this work, potential involvement of copper-dioxygen chemistry is explored by assessing effects of dioxygen on the copper(II) binding properties of F4W α-synuclein.1 Furthermore, since Met1 is the most susceptible residue to oxidation within the N-terminal copper(II) binding motif, Syn1-4 peptides (Scheme 1) containing methionine sulfoxide (M*) in place of Met1 were employed to examine potential effects upon oxidation, such as changes in metal binding affinity or polypeptide conformation. In addition, the possible existence of a cation-π interaction (CuII-Trp, CuII-Phe) is considered.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials and Methods

Peptides (MDVF, M*DVF, MDVW, and M*DVW; M*= methionine sulfoxide, 95 % purity) were purchased from AnaSpec, Inc. (San Jose, CA) and used as received; peptides were stored at –20 °C. Protein (F4W) was expressed and purified as previously described [16]. Sample homogeneity was verified by SDS-PAGE gel analyses visualized by silver-staining methods (Phastsystem, Amersham Biosciences). All purified proteins were concentrated using a Millipore Amicon Concentrator (MWCO 3kD), stored at −80 °C, and were filtered through Millipore Microcon YM-100 (MWCO 100kD) spin filter units to remove any oligomeric material prior to experiments. Tryptophan containing peptides and protein concentrations were determined using a value for molar absorptivity estimated on the basis of amino-acid content: ε280 nm = 5,500 M−1cm−1 (peptides) and ε280 nm = 10,810 M−1cm−1 (F4W). Concentrations of the phenylalanine containing peptides were determined gravimetrically.

Copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate (CuIISO4 • 5 H2O; Sigma-Aldrich 99.999 %) was stored in a dessicator. Deionized water for anaerobic copper stock solutions (vide infra) and pH 7.0 buffer solutions containing 20 mM 3-{N-morpholino}propanesulfonic acid (MOPS; SigmaUltra > 99.5 %) and 100 mM sodium chloride (NaCl ; Sigma 99.5 %) were sterile filtered (0.22 μm) and stored under an inert atmosphere (10 % H2, 90% N2) within a glovebox (Coy Laboratory Products; Grass Lake, Michigan) following thorough deoxygenation via standard Schlenk techniques. Tryptophan fluorescence was measured using a Horiba Jobin Yvon Fluorolog-3 spectrofluorimeter (λex = 295 nm, λobs = 300 – 500 nm, slit widths = 2 nm). Data were analyzed as previously published using the program IGOR 6.01 (Wavemetrics) [16]. Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were collected on a Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter using a 1 cm quartz cuvette (λobs = 200 – 400 nm; bandwidth = 1 – 2 nm; scan rate = 200 nm/min; accumulation = 5). Absorption data was collected on a Cary 300 Bio or Agilent 8453 spectrophotometer.

2.2. Anaerobic Copper(II) Titrations

Copper(II) stock solutions were prepared by dissolution of ~ 1 g of CuIISO4 • 5 H2O in ~ 10 mL deionized water. The copper(II) concentration was calculated based on the known molar absorptivity (ε = 11 M−1 cm−1) of the d-d transitions at 833 nm and the final copper(II) stock concentration was then adjusted to 3.75 mM. The copper(II) stock solution was then introduced to the glovebox in a small screw-cap tube (1.5 mL) and opened to the inert atmosphere for a minimum of 1 h prior to preparation of serially diluted stocks ranging in concentrations from 3.75 μM to 3.75 mM. Each vial was then fitted with a rubber septum and sealed with a crimper for removal from the glovebox. Protein and peptide samples were prepared in the glovebox using deoxygenated buffer solution (20 mM MOPS, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.0) and removed from the glovebox in 1 cm screw-capped quartz cuvettes. Copper(II) additions to protein and peptide samples (2 μL aliquots) were conducted on the benchtop using a Kloehn 5 μL syringe and the samples were equilibrated by stirring for 5 min before data collection.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Copper(II) binding to the F4W protein and Syn1-4 peptides

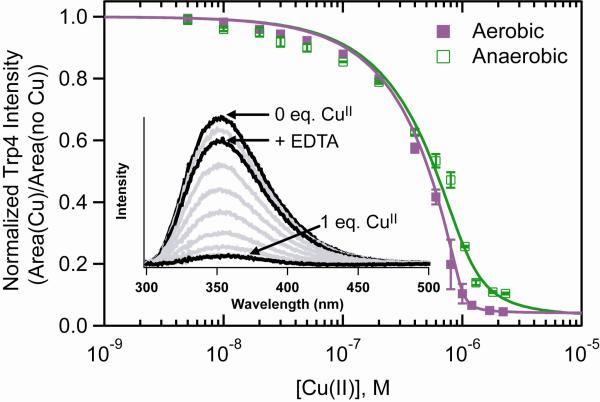

We have exploited the fluorescent amino acid Trp as a site-specific probe of CuII-protein/peptide interaction. Due to its high sensitivity, fluorescence spectroscopy is particularly suitable for the determination of a wide range of apparent dissociation constants (Kd(app)) near physiological temperatures and concentrations. While all previous studies were conducted on deoxygenated samples, we have characterized the CuII-F4W and CuII-Syn1-4 interaction in the presence of O2 (ambient air).2 Upon addition of CuII (5 nM – 2 μM), Trp4 fluorescence is dramatically quenched both in the presence and absence of O2 (Figure 1). Notably, the presence of O2 appears to enhance metal-binding as reflected by increased fluorescence quenching. Apparent dissociation constants extracted from fits to a single binding site model (Cu + α-syn ⇆ Cu-syn) suggest that the binding affinity is increased by an order of magnitude in the presence of dioxygen, Kd(app)(aerobic) ~ 10 nM and Kd(app)(anaerobic) ~ 100 nM.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Trp4 fluorescence intensity of CuII-F4W α-synuclein ([F4W] = 1 μM) under aerobic and anaerobic solution conditions (20 mM MOPS, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, 25 °C). Error bars represent standard deviations. Fits to a single binding site are shown as solid lines. Inset: Representative Trp fluorescence spectra as a function of added CuII ions in the presence of O2 (F4W alone, 1:1 CuII-F4W, and CuII-F4W + EDTA spectra are highlighted).

Since the CuII titrations were conducted at protein concentrations (1 × 10−6 M) greater than the Kd(app) value (< 1 × 10−7 M), there are greater uncertainties associated with these values. Regardless, it is clear from our data that the presence of O2 can modulate CuII binding to α-syn. Interestingly, a comparable Kd(app) value for the wild-type protein (2.4 nM, pH 7.2) was recently reported for experiments conducted in the presence of competitive CuII ligands, Gly, using isothermal calorimetric methods [15].

In order to verify that F4W emission could be restored once the copper(II) ion is extracted, the metal chelating agent, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) was added. In the absence of O2 only a minor effect is observed for F4W with the recovery yield increasing from 78% to 80%. To ensure that these differences cannot be attributed to deleterious photochemical reactions in the presence of O2, the model compound N-acetyltryptophanamide was tested, and resulted in no quenching under comparable experimental conditions.

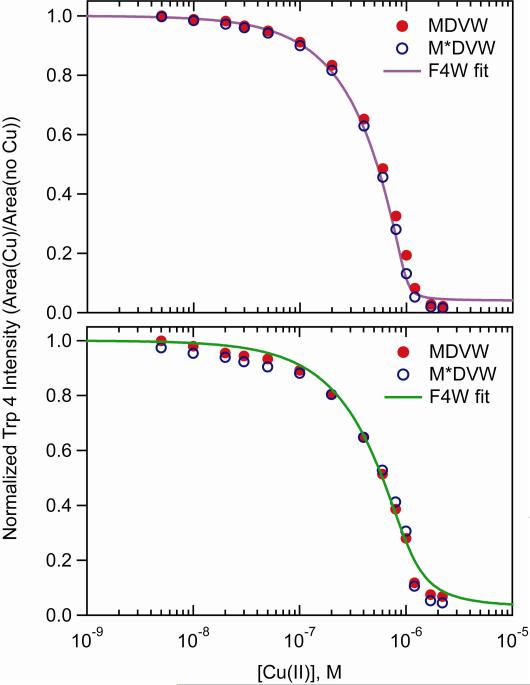

Since methionine residues are susceptible to oxidative chemistry, we employed a synthetic peptide with Met1 substituted with methionine sulfoxide (M*) to evaluate whether the O2 dependence on CuII binding is owing to Met1 oxidation (Scheme 1). Similar to F4W, the copper(II) binding affinity of the Trp containing Syn1-4 peptides are slightly enhanced in the presence of dioxygen (Figure 2); the enhancement is slightly greater for M*DVW. In the absence of dioxygen, the copper(II) binding affinity of these two peptides closely matches the full length protein (Figure 2). Upon removal of bound CuII ions with the addition of EDTA under both anaerobic and aerobic conditions, the original Syn1-4 fluorescence intensity is restored (85% to 95%).

Figure 2.

Comparison of copper(II) binding curves for aerobic (top) and anaerobic (bottom) solution conditions ([protein/peptide]= 1 μM in 20 mM MOPS, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7; M*=methionine sulfoxide).

3.2. Circular dichroism spectroscopic analysis of Syn1-4 peptides

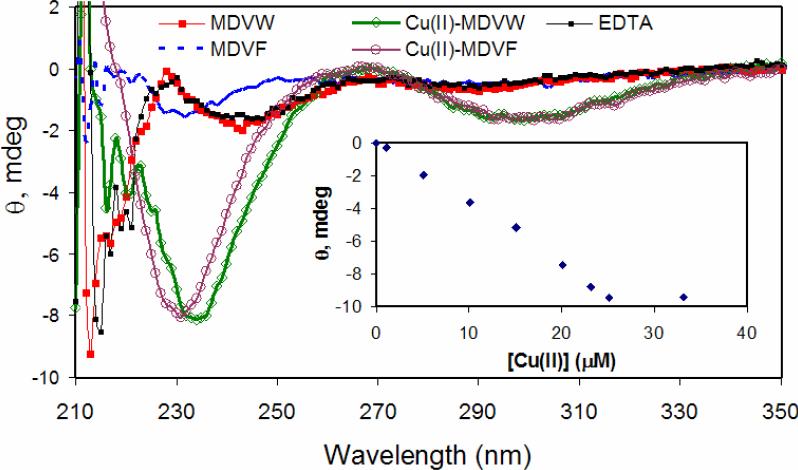

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy was employed to monitor conformational changes of Syn1-4 with coordination of copper(II). For the Phe containing N-terminal peptides, the minimum at 230 nm becomes more intense upon addition of one equivalent of copper(II) (Figure 3). A similar increase in intensity is observed for the Trp-containing Syn1-4 peptides. Additionally, the minimum centered at 243 nm shifts to 233 nm upon coordination of copper(II). For all four N-terminal peptides, saturated ellipticity (Θ) minima centered at 300 nm and maxima at 267 nm are reached following addition of one equivalent of copper(II) (Figure 3). These observed features are characteristic of CuII-peptide complex formation [18]. The lower energy minimum (Θ300 nm), is assigned to a charge transfer (CT) transition between the deprotonated peptide nitrogen and the copper(II) center (CuII-N−) and the 267 nm maximum is assigned to a NH2 → CuII CT transition, analogous to previous reports for α-syn [13, 19, 20]. The exact designation of Θ233 nm is difficult to assign, vide infra. Addition of EDTA to the 1:1 CuII-Syn1-4 complex, i.e. extraction of copper(II), resulted in the peptide returning to the initial unstructured conformation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Anaerobic titration of copper(II) to Syn1-4 (MDVW and MDVF) monitored by circular dichroism spectroscopy ([peptide]= 30 μM in 20 mM MOPS, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7) and addition of EDTA. Inset: A plot of Θ233 nm versus [CuII] for MDVW.

The higher energy minimum (Θ230, 233 nm) is reminiscent of the spectroscopic signature (Θ223 nm) assigned to a Cu-Trp cation-π interaction in a recent report by Takeuchi and coworkers on copper(II) binding to neuromedin C (NMC), a decapeptide involved in smooth muscle contraction [21]. The native NMC copper(II) binding site (GNHW) is thought to be composed of the free N-terminal nitrogen (NH2), two deprotonated amide backbone nitrogens (N–), a histidine (Nim), and a CuII-Trp cation-π interaction. Interestingly, the negative, lower energy minimum at ~300 nm was not observed for NMC even though CuII-N– interactions are believed to exist. Considering the higher energy band for Syn1-4 (Θ233 nm) is more red-shifted (Δλ = 10 nm) than NMC (Θ223 nm), it is plausible that a comparable lower energy band for NMC could be outside the measured spectral window (λmon = 180 – 300 nm) in the aforementioned study.

If we attribute this high energy feature (Θ233 nm) for Syn1-4 to the formation of a cation-π (CuII-Trp/Phe) interaction, then what factors could account for the 10 nm red shift difference? A similar intense minimum centered at 222 nm also was reported by Viles et. al. for copper(II) binding to the octapeptide region of prion protein [22]. However, based on the copper-peptide (HGGGW) crystal structure by Millhauser and coworkers, the indolyl sidechain of the Trp is hydrogen bonded to the axial water molecule and therefore not π-stacked with the cupric ion [23]. It is possible that a similar hydrogen bonding network exists in NMC accounting for the analogous CD feature at 223 nm. Since only minor spectral differences exist for Syn1-4 when the aromatic group changes from Trp to Phe, and since the latter cannot hydrogen bond, perhaps this band (233 nm) reflects a cation-π interaction and a blue shift (233 → 222 nm) results when hydrogen bonding occurs as demonstrated in the case in the prion peptide. On the contrary, it is also possible that the Θ230,233 nm minima for Syn1-4 suggest a completely different Cu-peptide conformation, involving neither cation-π nor a hydrogen bonding interaction.

4. Conclusion

Although copper is a redox-active metal ion, the cupric oxidation state is generally considered to be unreactive to dioxygen. However, based on our fluorescence quenching experiments, clear differences in the two titration curves are observed following addition of copper(II) to F4W in the presence and absence of dioxygen. Therefore, it is possible that the Trp4 emission is indicating a secondary copper(II) binding site of decreased affinity. However, since small changes were also observed for Syn1-4, this explanation seems less probable. Another more likely explanation is that Trp4 is sensing a contribution from copper(I), the more reactive redox state. The “soft” CuI ion would likely have a lower affinity for the N-terminal binding site due to the “hard” N–amide backbone resulting in a higher Kd value. In the presence of O2, re-oxidation of CuI-Syn could occur leading to the enhanced affinity.

Indeed, the reduction of copper(II) to copper(I) has been suggested for Aβ, the amyloidogenic peptide implicated in Alzheimer's disease [1, 24]. For Aβ, the Met35 residue has been proposed as an electron donor for the reduction of CuII-Aβ to CuI-Aβ, therefore a similar electron transfer pathway is feasible for CuII/I-Syn. We anticipate that if Met oxidation (Met → Met-O) as well as metal reduction (CuII → CuI) is occurring then the metal-protein affinity would be altered. This would possibly account for the differences in the Kd values reported herein. However, more work on α-syn is necessary before considering the specific involvement of Met1 or Met5 as an endogenous antioxidant and/or the role of copper(I) ion.

Since the primary copper(II) coordination site of α-syn is within the first four N-terminal residues, the effect of Met1 oxidation on the CuII binding affinity as well as the peptide conformation was probed using the Syn1-4 peptides. Our CD spectroscopic and Trp4 fluorescence quenching data demonstrate that Met1 oxidation had little effect on the CuII-Syn1-4 conformation. Generally, replacement of Met with M* leads to a decrease in side-chain flexibility, an increase in side-chain polarity and steric bulk as well as a potential H-bond acceptor site [25]. As a result, it is surprising that a conformational change was not observed upon CuII-Syn1-4 formation. However, a greater effect may result during aggregation and fibrillation. For example, early reports from Fink and coworkers suggested that methionine oxidation inhibits fibrillation of α-synuclein at neutral pH except in the presence of certain metals [26], while Leong et. al. recently reported that Met oxidation is required for dopamine to generate soluble α-syn oligomers [27].

The spectral features observed within the CD spectra do suggest, however, the existence of a cation-π interaction between the CuII ion and the Phe and Trp residue. Cation-π interactions are a recent addition to conventional copper-protein interactions as a result of the X-ray crystal structural characterization of the copper chaperone CusF [28-30]. The suggested role of the CuI-Trp interaction within CusF is to protect the metal ion from unwanted removal or oxidation so perhaps this proposal can be extended to the role of Phe4 (or Trp4) in α-syn.

Although oxidation of Met1 had little effect on the copper(II) binding affinity, it is expected that a larger effect would be observed upon copper(I) binding. Copper(I) has a greater potential of producing ROS in the presence of O2 or H2O2 and in turn may lead to enhanced oxidative stress in vivo. As a result, future experiments will be directed at examining the effect of dioxygen on copper(I) binding to α-syn and the possible role of Met1 as a ligand will be evaluated.

Acknowledgements

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. We thank Dr. Duck-Yeon Lee (Protein Analysis Facility) for maintaining the anaerobic glovebox and Dr. Grzegorz Piszczek (Biophysical Facility) for help with the circular dichroism measurements.

Abbreviations

- Aβ

Amyloid β

- α-syn

α-synuclein

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- NAC

non-amyloid component

- M*

methionine sulfoxide

- MOPS

3-{N-morpholino}propanesulfonic acid

- CD

circular dichroism

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- NMC

neuromedin C

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All of our previous work was conducted under anaerobic conditions.

No apparent differences were observed using O2 saturated solutions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gaggelli E, Kozlowski H, Valensin D, Valensin G. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:1995–2044. doi: 10.1021/cr040410w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skovronsky DM, Lee VMY, Trojanowskiz JQ. Annu. Rev. Pathol.-Mech. 2006;1:151–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnham KJ, Bush AI. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008;12:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Que EL, Domaille DW, Chang CJ. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:1517–1549. doi: 10.1021/cr078203u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole NB, Murphy DD, Lebowitz J, Di Noto L, Levine RL, Nussbaum RL. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:9678–9690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409946200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabner BJ, Turnbull S, El-Agnaf O, Allsop D. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2001;1:507–517. doi: 10.2174/1568026013394822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown DR. Dalton T. 2009:4069–4076. doi: 10.1039/b822135a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Binolfi A, Rasia RM, Bertoncini CW, Ceolin M, Zweckstetter M, Griesinger C, Jovin TM, Fernandez CO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9893–9901. doi: 10.1021/ja0618649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright JA, Wang X, Brown DR. FASEB J. 2009;23:2384–2393. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-130039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu M, Li J, Fink AL. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:40186–40197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasia RM, Bertoncini CW, Marsh D, Hoyer W, Cherny D, Zweckstetter M, Griesinger C, Jovin TM, Fernandez CO. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:4294–4299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407881102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sung YH, Rospigliosi C, Eliezer D. BBA-Proteins Proteom. 2006;1764:5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Binolfi A, Lamberto GR, Duran R, Quintanar L, Bertoncini CW, Souza JM, Cervenansky C, Zweckstetter M, Griesinger C, Fernandez CO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:11801–11812. doi: 10.1021/ja803494v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drew SC, Leong SL, Pham CLL, Tew DJ, Masters CL, Miles LA, Cappai R, Barnham KJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:7766–7773. doi: 10.1021/ja800708x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong L, Simon JD. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:9551–9561. doi: 10.1021/jp809773y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JC, Gray HB, Winkler JR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6898–6899. doi: 10.1021/ja711415b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson MJ, Lee JC. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:9303–9307. doi: 10.1021/ic901157w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sigel H, Martin RB. Chem. Rev. 1982;82:385–426. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kowalik-Jankowska T, Rajewska A, Wisniewska K, Grzonka Z, Jezierska J. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2005;99:2282–2291. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kowalik-Jankowska T, Rajewska A, Jankowska E, Grzonka Z. Dalton T. 2006:5068–5076. doi: 10.1039/b610619f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yorita H, Otomo K, Hiramatsu H, Toyama A, Miura T, Takeuchi H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:15266–15267. doi: 10.1021/ja807010f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viles JH, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Goodin DB, Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:2042–2047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burns C, Aronoff-Spencer E, Dunham C, Lario P, Avdievich N, Antholine W, Olmstead M, Vrielink A, Gerfen G, Peisach J, Scott W, Millhauser G. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3991–4001. doi: 10.1021/bi011922x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Multhaup G, Schlicksupp A, Hesse L, Beher D, Ruppert T, Masters CL, Beyreuther K. Science. 1996;271:1406–1409. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5254.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karunakaran-Datt A, Kennepohl P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3577–3582. doi: 10.1021/ja806946r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fink AL. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:628–634. doi: 10.1021/ar050073t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leong SL, Pham CLL, Galatis D, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Perez K, Hill AF, Masters CL, Ali FE, Barnham KJ, Cappai R. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2009;46:1328–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucas HR, Karlin KD. Met. Ions Life Sci. 2009;6:295–362. doi: 10.1039/BK9781847559159-00295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xue Y, Davis AV, Balakrishnan G, Stasser JP, Staehlin BM, Focia P, Spiro TG, Penner-Hahn JE, O'Halloran TV. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:107–109. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loftin IR, Franke S, Blackburn NJ, McEvoy MM. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2287–2293. doi: 10.1110/ps.073021307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]