Abstract

Objectives To determine whether the UK Clinical Aptitude Test (UKCAT) adds value to the selection process for school leaver applicants to medical and dental school, and in particular whether UKCAT can reduce the socioeconomic bias known to affect A levels.

Design Cohort study

Setting Applicants to 23 UK medical and dental schools in 2006.

Participants 9884 applicants who took the UKCAT in the UK and who achieved at least three passes at A level in their school leaving examinations (53% of all applicants).

Main outcome measures Independent predictors of obtaining at least AAB at A level and

UKCAT scores at or above the 30th centile for the cohort, for the subsections and the entire test.

Results Independent predictors of obtaining at least AAB at A level were white ethnicity (odds ratio 1.58, 95% confidence interval 1.41 to 1.77), professional or managerial background (1.39, 1.22 to 1.59), and independent or grammar schooling (2.26, 2.02 to 2.52) (all P<0.001). Independent predictors of achieving UKCAT scores at or above the 30th centile for the whole test were male sex (odd ratio 1.48, 1.32 to 1.66), white ethnicity (2.17, 1.94 to 2.43), professional or managerial background (1.34, 1.17 to 1.54), and independent or grammar schooling (1.91, 1.70 to 2.14) (all P<0.001). One major limitation of the study was that socioeconomic status was not volunteered by approximately 30% of the applicants. Those who withheld socioeconomic status data were significantly different from those who provided that information, which may have caused bias in the analysis.

Conclusions UKCAT was introduced with a high expectation of increasing the diversity and fairness in selection for UK medical and dental schools. This study of a major subgroup of applicants in the first year of operation suggests that it has an inherent favourable bias to men and students from a higher socioeconomic class or independent or grammar schools. However, it does provide a reasonable proxy for A levels in the selection process.

Introduction

Selection to highly competitive UK degree courses such as medicine and dentistry needs to be appropriate, fair, and transparent.1 Unfortunately, the validity and reliability of many current selection practices is questionable.2 The great majority of school leavers in the United Kingdom take advanced level (“A level”) examinations in their final year in secondary school. Their performance in these academic tests is the main criterion by which universities select students for higher education. Over recent years the average A level score has progressively risen (“grade inflation”). With A level grade inflation, discriminating between large numbers of highly able applicants on their academic achievement alone is becoming increasingly difficult.3 Furthermore, selectors now wish to assess applicants specifically on attributes deemed desirable for healthcare professionals. Widening participation is high on the political agenda,4 and some admission policies seek to achieve this by selecting candidates on the basis of identified aptitude rather than solely academic achievement, which is dependent on both school background and other socioeconomic factors.5

These concerns catalysed the development of the UK Clinical Aptitude Test (UKCAT), which was first used in 2006 as an entrance test as part of the admissions process used by a consortium of 23 UK medical and dental schools. The test was developed by Pearson VUE and its associates,6 in collaboration with representatives of the participating medical and dental schools. The test is an appraisal of aptitudes and is designed to ensure that candidates have the most appropriate mental abilities, attitudes, and professional behaviours for new doctors and dentists to be successful in their professional careers.7 The aim was to use selection methods that might be less subject to bias than are A levels.

Alongside designing and delivering the test, the UKCAT Consortium is responsible for a planned research programme. This aims to provide the evidence that the UKCAT can effectively and appropriately facilitate the selection process of doctors and dentists. This paper is the first of a series reporting analyses of the data from the first cohort of applicants to medical and dental school who sat the UKCAT in 2006 for entry in 2007. It explores the relation between applicants’ UKCAT scores and the current “gold standard” in selection, A level grades and their corresponding tariff points. We also examine the possible effects of socioeconomic factors on these assessment measures.

Methods

We included students who applied in 2006 to study medicine or dentistry in the UK, and who sat the UKCAT in July-October 2006. Data came from two sources, UKCAT and the Universities and Colleges Admissions Scheme (UCAS—a national body that coordinates the admission of students to higher education in the UK). The UKCAT data comprised socioeconomic data provided by students when they registered with Pearson VUE to take the test and the results from those tests. At registration, students were informed that this information would be used solely for the purposes of educational research, evaluation of the UKCAT, and quality control of the selection process and that the results would be published in medical, educational, and other academic publications in aggregate or other forms in which individual students cannot be identified. The UCAS data included students’ recent school examination performance (up to and including summer 2007) and the type of school attended.

In 2006 the UKCAT assessed the cognitive powers considered to be valuable for healthcare professionals through four sub-tests: verbal reasoning, quantitative reasoning, abstract reasoning, and decision analysis. Each sub-test is timed and scored separately; the whole test took 90 minutes to complete in 2006. Candidates take the onscreen test at a Pearson VUE centre after registering online and are given their results before leaving the test centre. They then can use these results to help them decide whether to apply to a specific medical or dental school if UKCAT criteria are included in the admissions policy.

Data preparation

Socioeconomic data collected by UKCAT included date of birth, used to calculate the age in years when the test was taken (we also recoded this into a binary variable of ≤19 v >19); sex; ethnicity (raw data included white, Asian, Chinese, black, mixed race, other, or not declared, and we collapsed these categories into a binary variable of white v non-white); and socioeconomic status. Candidates were asked to supply data on their parents’ or carers’ occupations, using the categories used by the National Statistics socioeconomic classification, self coded version (NS-SEC).8 This scheme requires details of the type of job done; whether self employed or employed, and, if relevant, managerial status; and the size of the employing organisation. We combined these factors by using an algorithm to derive the NS-SEC category for the sole or highest scoring parent/carer, in five groups: managerial and professional, intermediate, small employers and own account workers, lower supervisory and technical, and semi-routine and routine occupations. We further collapsed these into managerial/professional versus all other categories. The UKCAT test data comprised the scores for each sub-section of the test and the overall total score.

UCAS data included passes in all school examinations taken in the United Kingdom over the previous 18 months, as provided to UCAS by the awarding body linkage (see web appendix). For the purposes of this study, only passes at advanced level have been included. We awarded these tariff scores as used by UCAS (that is, A=120 points, B=100, C=80, D=60, E=40), and totalled and averaged them for all subjects apart from general studies and critical thinking, which we excluded. We also created a total and average tariff point score for all sciences (which included all chemistry, biology, physics, and mathematics subjects, but not applied sciences). In addition, we created an A level band, coded according to each candidate’s top three passes; these bands were AAA, AAB, ABB, BBB, or any other combination (for example, two As but no Bs). School type was provided in five categories (see web appendix): grammar, independent, or other maintained; comprehensive or sixth form college/centre; further/higher education; other (unclassified); not stated. We coded these separately and also collapsed them into a binary variable of independent/grammar versus all other categories.

Data analysis

We used SPSS v15 for data analysis. The distributions of scores for both A level tariff points and the UKCAT test were non-normal (one way Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P<0.001), so we used non-parametric methods. After an initial descriptive analysis, we used the Mann-Whitney U test to examine the effects of the explanatory variables sex, ethnicity (as white or non-white), socioeconomic group (as managerial/professional or other), and schooling (as independent/grammar or other) on the outcome variables of UKCAT scores and A level scores. We excluded missing data from the analysis with no substitution or imputation. We examined bivariate correlation between UKCAT and A level scores with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

We also examined the median UKCAT scores within each of the A level bands and used the Kruskal-Wallis test to compare these. We then collapsed the A level bands into AAA/AAB or lower (AAB being the lowest score accepted by most medical schools). Similarly, we collapsed the UKCAT scores into those at or above the 30th centile and those below it; this created a binary marker for a “high score” in both A levels and UKCAT. We used these to compare the effects of the explanatory variables by using the χ2 test. We chose the 30th centile because this corresponded best to the weighting of the A level scores. However, we acknowledge that these are not directly comparable analyses.

Finally, we used hierarchical binary logistic regression to examine the independent predictors of high scores in both UKCAT and A levels. The first block of explanatory variables included the “primary” characteristics of sex and ethnicity; the second block included the “secondary” factors of socioeconomic classification and school type. The outcome variables were the binary variables described above for high scores in either UKCAT or A levels.

Results

Study group

Overall, 18 542 applicants sat the UKCAT in 2006. This was a heterogeneous group comprising applicants domiciled in the UK, Europe, and overseas, as well as school leavers and applicants who were not school leavers but were either employed or in higher education (“mature applicants”) to both medical and dental schools in the UK. For the purposes of this study, we analysed the results of only UK domiciled applicants who had at least three recent A levels. This would allow meaningful comparison of contemporaneous qualifications and socioeconomic data. We included 9884 applicants (53% of the total population that sat UKCAT) in the study.

Table 1 shows the socioeconomic characteristics of the selected study group (n=9884), including type of school. For comparison, the equivalent data for the non-selected part of the 2006 UKCAT cohort (n=8658) are also shown. As expected, almost all the applicants in the study group were aged 19 or under when they sat the UKCAT test, compared with 61% in the non-study group. Approximately 56% of both groups were female. The study group had more white and Asian applicants and fewer Chinese applicants. Where the data were available, occupation and socioeconomic categories were similar in both groups.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic characteristics of study and non-selected groups. Values are numbers (percentages)

| Characteristic | Study group (UK students with ≥3 A levels) (n=9884) | Non-selected group (all others) (n=8658) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group when test taken: | 9754 (98.7) | 5297 (61.2) |

| 16-19 | ||

| 20-24 | 77 (0.8) | 2395 (27.7) |

| 25-34 | 20 (0.2) | 789 (9.1) |

| ≥35 | 5 (0.1) | 138 (1.6) |

| <16 or missing | 28 (0.3) | 39 (0.4) |

| Female sex | 5542 (56.1) | 4934 (57.0) |

| Ethnic group: | ||

| White | 5808 (58.8) | 4972 (57.4) |

| Asian | 2658 (26.9) | 1735 (20.0) |

| Chinese | 238 (2.4) | 532 (6.1) |

| Black | 402 (4.1) | 398 (4.6) |

| Mixed race | 357 (3.6) | 283 (3.3) |

| Other | 272 (2.8) | 590 (6.8) |

| Not declared | 149 (1.5) | 148 (1.7) |

| Highest NS-SEC in family: | 5716 (57.8) | |

| Managerial/professional | 4970 (57.4) | |

| Intermediate | 376 (3.8) | 277 (3.2) |

| Small employer/own account worker | 499 (5.0) | 462 (5.3) |

| Lower supervisory/technical | 175 (1.8) | 147 (1.7) |

| Semi-routine/routine | 239 (2.4) | 183 (2.1) |

| Unknown (withheld, not known) | 2879 (29.1) | 2619 (30.2) |

| Schooling: | ||

| Independent/grammar school | 4602 (46.6) | 1271 (14.7) |

| Comprehensive/sixth form college or centre | 4310 (43.6) | 1301 (15.0) |

| Further/higher education | 537 (5.4) | 1667 (19.3) |

| Other (unclassified) | 340 (3.4) | 431 (5.0) |

| Not stated | 95 (1.0) | 3988 (19.4[46.1?]) |

NS-SEC=National Statistics socioeconomic classification.

The applicants in the study group were distributed almost equally between our two major categories of secondary schooling (independent/grammar and comprehensive/sixth form college). Comparable data are not available for all the non-selected applicants because we did not receive this information for mature or overseas students who had not sat recent UK school examinations.

UKCAT and A level performance in study group

Table 2 summarises the UKCAT scores of the study group. The distributions of UKCAT scores were significantly non-normal (P<0.001 after Kolmogorov-Smirnov test).

Table 2.

Performance in UKCAT. Values are medians (interquartile ranges)

| Score | Study group (n=9884) |

|---|---|

| Verbal reasoning | 600 (540-650) |

| Quantitative reasoning | 620 (570-650) |

| Abstract reasoning | 600 (560-660) |

| Decision analysis | 590 (530-660) |

| Total for all sections | 2420 (2260-2570) |

UKCAT=UK Clinical Aptitude Test.

The study group by definition had at least three A level passes, but 30% had four or more. Virtually all had at least two passes in sciences (this category included biology, human biology, chemistry, physics, and all variants of mathematics, but excluded subjects such as applied science, accounting, or computing). Most medical and dental schools require entrants to have at least one A grade in science, usually chemistry; some require an A grade in both chemistry and biology. Of the study group, 23% had an A grade in one of these subjects and 50% had A grades in both. Nearly half the group also had A grades in physics, maths, or both, and 37% had an A grade in another subject (excluding general studies).

Table 3 shows the distribution of A level passes into the “bands” described above. Thus, 68% had achieved at least AAB, required by most medical and dental schools, and only 17% achieved less than BBB. This group would include those with, for example, two A grades but no Bs.

Table 3.

“Banding” of three highest A level scores. Values are numbers (percentages)

| A level band | Study group (n=9884) |

|---|---|

| AAA or better | 4984 (50.4) |

| At least AAB | 1771 (17.9) |

| At least ABB | 1039 (10.5) |

| At least BBB | 407 (4.1) |

| All other combinations | 1683 (17.0) |

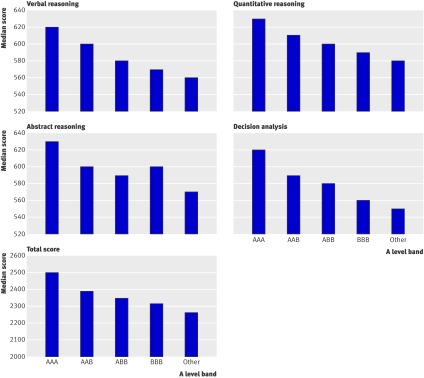

The figure shows the UKCAT scores achieved within each A level band. Most of the distributions were non-normal, so median scores are shown. A consistent drop in performance in the UKCAT scores occurred with each fall in A level band, and this was highly significant in all cases (P<0.001, Kruskal-Wallis test). The only exception to the downward trend was for abstract reasoning, in which the “BBB” group performed better than expected.

Median UKCAT scores by A level band

Web table A shows the correlation matrix between UKCAT and A level total tariff, both for all subjects and for sciences. The four sections of the UKCAT show a modest correlation between themselves; the highest correlation was between verbal and quantitative reasoning (r=0.406) and the lowest between verbal and abstract reasoning (r=0.288). A similar degree of correlation existed between A level tariff score and total UKCAT score (r=0.392), but the sub-sections correlated less well with tariff score, ranging between 0.267 for abstract reasoning and 0.300 for quantitative reasoning. All correlations were highly significant (P<0.001).

Influence of socioeconomic variables on UKCAT and A level scores

Web table B shows the results of the univariate analysis. Various data were missing as a result of unreported ethnicity, parental occupation, and schooling. Also, 21 applicants did not achieve any passes in science A levels, so their tariff scores in this category are zero and they have no average science tariff.

The results from these analyses can be summarised as follows. Male applicants performed better than female applicants in verbal reasoning and quantitative reasoning and overall in the UKCAT test, but they did less well in abstract reasoning. The largest differential was in quantitative reasoning. These differences were all highly statistically significant (P<0.001), although the actual differences in median scores were small. We found no difference between the sexes in decision analysis. Male applicants also performed better in terms of A level total tariff and total science tariff scores, but not in average tariff scores and only slightly (P=0.001) in average science tariff scores. White students performed better than non-white students in all parameters (P<0.001) apart from the total science tariff. The differences were greatest for verbal reasoning, decision analysis, and total UKCAT score. For the 71% of candidates with valid socioeconomic data, those from the top professional/managerial backgrounds performed significantly better in all parameters than did those from all other backgrounds (P<0.001 in all cases). Applicants from independent/grammar schools also performed better than others in all parameters (P<0.001 in all cases).

In view of the lack of information on socioeconomic status for 30% of the study group, we examined the potential limitations that resulted. We created a new variable to denote whether socioeconomic status was known and then did χ2 for this new variable against sex, ethnicity, and schooling, to examine the possible effect of the missing data. This analysis showed that candidates without known socioeconomic status were slightly more likely to be male (odds ratio 1.22, 95% confidence interval 1.12 to 1.33), less likely to be white (0.39, 0.36 to 0.43), and slightly less likely to be from independent/maintained/grammar schools (0.85, 0.78 to 0.93) (P<0.001 in all cases). Candidates with unknown socioeconomic status were also less likely to score at or above the 30th centile for UKCAT or to have high A level banding. For the UKCAT, the odds ratios varied between 0.58 (0.53 to 0.63) for the total score and 0.77 (0.70 to 0.85) for quantitative reasoning; for A levels, the odds ratio was 0.67 (0.61 to 0.73).

Multivariate analysis: independent predictors of UKCAT and A level scores

Linear regression analysis was not a suitable statistical test for independent predictors, because of the non-normal distributions of UKCAT and A level scores. Instead, we created simple binary markers of achievement so that binary logistic regression could be used. For A levels, we used the banding variable to select those applicants who had achieved the minimum requirement for admission—that is, AAA or AAB for their top three passes. This selected out the top 68% of candidates. For UKCAT, we calculated the 30th centile and set a “high score” marker for scores at or above this level. We then used univariate analysis (χ2 tests) to test these two outcomes against socioeconomic predictors; tables 4 and 5 show summary statistics. These confirm the results of the Mann-Whitney tests (above), in relation to the UKCAT scores. For A level banding, male candidates were not significantly better than female candidates, but white ethnicity and professional/managerial background did confer a significant advantage, and the strongest effect was from schooling.

Table 4.

Univariate (χ2) analysis of binary predictor variables against A level band

| Characteristic | Outcome | Pearson χ2 | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex (n=9884) | High A level band | 3.60 | 0.058 | |

| White ethnicity (n=9735) | High A level band | 152.35 | <0.001 | 1.72 (1.58 to 1.88) |

| Professional/managerial background (n=7005) | High A level band | 55.35 | <0.001 | 1.62 (1.42 to 1.83) |

| Independent/grammar schooling (n=9790) | High A level band | 350.74 | <0.001 | 2.32 (2.12 to 2.53) |

Odds ratios are quoted for given characteristic against “high band” (AAA or AAB for top 3 passes).

Table 5.

Univariate (χ2) analysis of binary predictor variables against higher UKCAT scores (at or above 30th centile)

| Characteristic | Test score* | Pearson χ2 | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex (n=9884) | UKCAT VR | 42.80 | <0.001 | 1.34 (1.23 to 3.53) |

| UKCAT QR | 173.00 | <0.001 | 1.83 (1.67 to 2.00) | |

| UKCAT AR | 16.30 | <0.001 | 0.84 (0.77 to 0.91) | |

| UKCAT DA | 0.94 | NS | ||

| UKCAT Total | 34.53 | <0.001 | 1.30 (1.19 to 1.42) | |

| White ethnicity (n=9735) | UKCAT VR | 670.90 | <0.001 | 3.22 (2.95 to 3.53) |

| UKCAT QR | 145.46 | <0.001 | 1.72 (1.57 to 1.88) | |

| UKCAT AR | 65.61 | <0.001 | 1.44 (1.32 to 1.57) | |

| UKCAT DA | 255.22 | <0.001 | 2.10 (1.91 to 2.30) | |

| UKCAT Total | 472.70 | <0.001 | 2.65 (1.19 to 1.42) | |

| Professional/managerial background (n=7005) | UKCAT VR | 44.88 | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.37 to 1.77) |

| UKCAT QR | 27.72 | <0.001 | 1.42 (1.24 to 1.61) | |

| UKCAT AR | 18.78 | <0.001 | 1.34 (1.17 to 1.53) | |

| UKCAT DA | 49.03 | <0.001 | 1.61 (1.41 to 1.84) | |

| UKCAT Total | 53.12 | <0.001 | 1.62 (1.42 to 1.84) | |

| Independent/grammar schooling (n=9790) | UKCAT VR | 95.57 | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.42 to 1.70) |

| UKCAT QR | 112.03 | <0.001 | 1.61 (1.48 to 1.76) | |

| UKCAT AR | 112.61 | <0.001 | 1.61 (1.48 to 1.76) | |

| UKCAT DA | 143.14 | <0.001 | 1.75 (1.60 to 1.92) | |

| UKCAT Total | 258.22 | <0.001 | 2.08 (1.90 to 2.27) |

NS=not significant.

Odds ratios are quoted for given characteristic against achieving UKCAT scores ≥30th centile.

*UK Clinical Aptitude Test (UKCAT): VR=verbal reasoning sub-test; QR=quantitative reasoning sub-test; AR=abstract reasoning sub-test; DA=decision analysis sub-test.

We then subjected these data to multivariate binary logistic regression, using a hierarchical model in two blocks: the “primary” characteristics of sex and ethnicity and the “secondary” characteristics of parental socioeconomic status and schooling. Tables 6 and 7 show the results of these analyses. For UKCAT, male sex was a positive independent predictor of success in verbal reasoning, quantitative reasoning, and overall score but a weak negative predictor for abstract reasoning. It had no predictive influence in decision analysis. White ethnicity predicted success in all sections of the UKCAT apart from abstract reasoning, for which we found no influence. Professional/managerial background predicted success in all parts of the UKCAT but only weakly in quantitative and abstract reasoning. Schooling was an independent predictor throughout the test. For A levels, ethnicity, socioeconomic background, and schooling predicted being in the top A level band, although sex did not. The predictive effect of schooling was the strongest, with an odds ratio of 2.26. The amount of variance contributed by these four predictors was quite small in each case, especially for abstract reasoning.

Table 6.

Binary logistic regression: independent predictors of high banding (AAA or AAB) for top three A level passes

| Characteristic | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Variance contributed to model (Nagelkerke R2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1 | |||

| Male sex | 1.15 (1.03 to 1.27) | 0.012 | 0.014 |

| White ethnicity | 1.54 (1.39 to 1.72) | <0.001 | |

| Block 2 | |||

| Male sex | 1.11 (1.00 to 1.24) | 0.053 | 0.066 |

| White ethnicity | 1.58 (1.41 to 1.77) | <0.001 | |

| Professional/managerial background | 1.39 (1.22 to 1.59) | <0.001 | |

| Independent/grammar schooling | 2.26 (2.02 to 2.52) | <0.001 | |

As a result of missing data, regression equation contained only 6929 students (70% of total).

Table 7.

Hierarchical binary logistic regression: independent predictors of attaining UK Clinical Aptitude Test scores at or above 30th centile

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Variance contributed to model (Nagelkerke R2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal reasoning | |||

| Block 1: | |||

| Male sex | 1.55 (1.38 to 1.74) | <0.001 | 0.077 |

| White ethnicity | 2.80 (2.50 to 3.13) | <0.001 | |

| Block 2: | |||

| Male sex | 1.53 (1.37 to 1.72) | <0.001 | 0.087 |

| White ethnicity | 2.79 (2.49 to 3.12) | <0.001 | |

| Professional/managerial background | 1.29 (1.12 to 1.48) | <0.001 | |

| Independent/grammar schooling | 1.39 (1.24 to 1.55) | <0.001 | |

| Quantitative reasoning | |||

| Block 1: | |||

| Male sex | 1.97 (1.76 to 2.21) | <0.001 | 0.042 |

| White ethnicity | 1.58 (1.42 to 1.77) | <0.001 | |

| Block 2: | |||

| Male sex | 1.95 (1.74 to 2.19) | <0.001 | 0.057 |

| White ethnicity | 1.59 (1.42 to 1.78) | <0.001 | |

| Professional/managerial background | 1.26 (1.10 to 1.44) | 0.001 | |

| Independent/grammar schooling | 1.53 (1.38 to 1.71) | <0.001 | |

| Abstract reasoning | |||

| Block 1: | |||

| Male sex | 0.86 (0.78 to 0.96) | 0.007 | 0.004 |

| White ethnicity | 1.21 (1.08 to 1.35) | 0.001 | |

| Block 2: | |||

| Male sex | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.94) | 0.003 | 0.017 |

| White ethnicity | 1.20 (1.07 to 1.35) | 0.001 | |

| Professional/managerial background | 1.24 (1.08 to 1.41) | 0.002 | |

| Independent/grammar schooling | 1.46 (1.31 to 1.63) | <0.001 | |

| Decision analysis | |||

| Block 1: | |||

| Male sex | 1.14 (1.02 to 1.28) | 0.020 | 0.020 |

| White ethnicity | 1.74 (1.56 to 1.95) | <0.001 | |

| Block 2: | |||

| Male sex | 1.12 (1.00 to 12.6) | 0.050 | 0.042 |

| White ethnicity | 1.73 (1.54 to 1.95) | <0.001 | |

| Professional/managerial background | 1.40 (1.22 to 1.61) | <0.001 | |

| Independent/grammar schooling | 1.62 (1.44 to 1.82) | <0.001 | |

| Total score | |||

| Block 1: | |||

| Male sex | 1.51 (1.35 to 1.69) | <0.001 | 0.046 |

| White ethnicity | 2.13 (1.91 to 2.38) | <0.001 | |

| Block 2: | |||

| Male sex | 1.48 (1.32 to 1.66) | <0.001 | 0.078 |

| White ethnicity | 2.17 (1.94 to 2.43) | <0.001 | |

| Professional/managerial background | 1.34 (1.17 to 1.54) | <0.001 | |

| Independent/grammar schooling | 1.91 (1.70 to 2.14) | <0.001 | |

As a result of missing data, regression equations contained only 6929 students (70% of total).

Discussion

This paper presents the analysis of a selected part of the first cohort of medical and dental school candidates’ UKCAT scores compared with their A level results and socioeconomic variables, showing that UKCAT scores are modestly correlated to A level tariff scores but that some socioeconomic bias remains. As previously outlined, the introduction of an additional new selection tool is reasonable only if this improves the selection process both for and of medical and dental students. Selection currently relies very heavily on academic achievement. Discriminating between able candidates, usually on A level predictions, is becoming increasingly difficult and is compounded by A level grade inflation. The reliability and validity of screening applicants before interview by using applicants’ written personal statements and academic references has also been questioned. Therefore, medical and dental schools have high hopes that the UKCAT will be able to assist reliably and appropriately in selection of students. The relation between UKCAT scores and A levels needs to be examined and understood, particularly if universities increasingly use the UKCAT to screen candidates for interview. When using UKCAT scores, universities need to be reassured that applicants are not being unfairly discriminated against and, if possible, that wider participation is enabled.

Our finding that the total UKCAT score is modestly correlated to applicants’ eventual total A level tariff is reassuring if the UKCAT is being used by medical and dental schools as a proxy before final A level results are available. Additionally, the hope was that the UKCAT, especially the sub-test scores, could differentiate in ways that are different from A levels, and in a limited way our findings support this. For example, compared with A levels, the total UKCAT score confers some advantage to male candidates while slightly reducing the influence of selective schooling. The quantitative reasoning sub-test seems to be particularly favourable to male candidates. These effects are not marked, however. The UKCAT is distinguished from other admission tests because it does not examine acquired knowledge, and candidates cannot be “coached” to pass. It thus aims to provide a more equitable assessment of aptitude, but our data on this selected subgroup of the first cohort show that socioeconomic bias remains.

Components of the UKCAT were chosen as the best tests available to select for attributes that were considered to be important in medical and dental students, and later in qualified practitioners, and that complemented the academic screening provided by A levels. The first three sub-tests have been found to screen appropriate cognitive ability reliably in other fields.9 The more innovative decision analysis sub-test assesses candidates’ ability to make judgments under conditions of increasing complexity and ambiguity—attributes necessary for professional practice. However, no definitive advice has been available that informs us how each sub-test should be used in assessing candidates. Our results indicate that each sub-test is correlated to A level performance but less so than is the total UKCAT score. This finding, and the inherent socioeconomic bias, leads us to be cautious about use of the UKCAT and the value of any one specific sub-test within an admissions policy. It reinforces the need for further research.

Limitations of study

Only 53% of the total population that sat UKCAT in 2006 were included in the study. Although those included represent a large cohort, the exclusions reduce the diversity of the study group and the generalisability of the results. Similarly, to preserve the simplicity and ease of understanding of the analysis, we collapsed the many variables for the binary regression. This provided a broad overview of UKCAT performance, but such simplifications may hide subtle but important differences between the performance of different ethnic groups, for example. Similarly, we had to group schools according to the categories provided by UCAS, and each group will contain institutions and students of varying standards and abilities, which merits further investigation.

In common with many studies of this type involving socioeconomic data that are provided only voluntarily, an important amount of information was missing, predominantly owing to unknown parental occupation and hence socioeconomic status. This is particularly unfortunate because it is very relevant in the context of widening participation. The regression analyses contained only 70% of the data, and our secondary analysis of applicants with unknown socioeconomic status suggests that these candidates were significantly different in terms of characteristics and performance. Specifically, they were more likely to be male, non-white, and from non-selective schools. They were less likely both to have scored above the 30th centile in the UKCAT and to have achieved at least AAB at A level. Arguably, this group contained those candidates who were more likely to benefit from widening participation. The missing data are likely to have affected the absolute values of adjusted odds ratios, but we cannot speculate by how much.

Conclusions

We found a significant correlation between A level and UKCAT scores, which confirms that the UKCAT can be used as a reasonable proxy for A levels in the selection process. The test was introduced with high expectation of increasing the diversity and fairness in selection for UK medical and dental schools. This study of a major sub-group of applicants in the first year of operation suggests that it has an inherent favourable bias to male applicants and those from a higher socioeconomic class or from independent or grammar schools. Future studies will elucidate the practical value of the UKCAT in the wider range of applicants and, importantly, its predictive role in performance at medical or dental school.

What is already known on this topic

The validity and reliability of many practices for selection of medical and dental undergraduates in the UK are questionable

Discriminating between large numbers of highly able applicants on their academic achievement alone is increasingly difficult, and participation needs to be widened

The UK Clinical Aptitude Test (UKCAT) was first used as an entrance test as part of the admissions process by a consortium of 23 medical and dental schools in 2006

What this paper adds

In UK students with three or more A levels, UKCAT scores were modestly correlated to A level tariff scores but had inherent gender and socioeconomic bias

Compared with A levels, the total UKCAT score conferred some advantage to male applicants while slightly reducing the influence of selective schooling

We thank David Bennett and Rob Draisey at Pearson VUE for assistance with data extraction and interpretation. We also thank UCAS for permission to include their data and specifically Anna Daws for practical assistance. We acknowledge the contribution of Martin Bland in planning this study.

Contributors: All authors contributed to planning the research, analysing and interpreting the results, and drafting the paper, and all approved the final version. JY prepared and manipulated the dataset. DJ is the guarantor.

Funding: JY was funded by the UKCAT Board. The UKCAT Board is responsible for an overall research and evaluation programme, but the named authors are responsible for the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the paper as submitted. UKCAT is responsible for the database and agreed with the decision to submit the article for publication. The authors confirm their independence as researchers from UKCAT acting in this capacity as funders.

Competing interests: JY was funded by the UKCAT Board to complete the analysis. SN was elected as chair of the UKCAT Board in December 2008. However, no author has any ongoing financial interests in the publication of these results.

Ethical approval: Formal ethical approval was not needed for this analysis of anonymised, routinely collected data. Applicants for the UKCAT test were informed that their anonymised and aggregated data would be used for educational research and evaluation of the UKCAT on registration for the test. UCAS gave consent for UKCAT to use data in research and for this paper to be published. The UKCAT Board commissioned this research and approved the paper.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;340:c478

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Web appendix

Web table B

Web table A

References

- 1.Department for Education and Skills. Fair admissions to higher education: recommendations for good practice. 2004. www.admissions-review.org.uk/downloads/finalreport.pdf.

- 2.Ferguson E, James D, Madeley L. Factors associated with success in medical school: systematic review of the literature. BMJ 2002;324:952-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholson S. The benefits of aptitude testing for selecting medical students [commentary]. BMJ 2005;331:559-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department for Education and Skills. The future of higher education [white paper]. DfES, 2003.

- 5.Parry J, Mathers J, Stevens A, Parsons A, Lilford R, Spurgeon P, et al. Admissions processes for five year medical courses at English schools: review. BMJ 2006;332:1005-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearson VUE. About us: the world’s leading computer-based testing and assessment business. 2008. www.pearsonvue.co.uk/aboutus/pages/Aboutus.aspx.

- 7.UK Clinical Aptitude Test Consortium. The UK clinical aptitude test (UKCAT). 2009. www.ukcat.ac.uk/default.aspx.

- 8.Office for National Statistics. Self-coded version of the NS-SEC. 2008. www.ons.gov.uk/about-statistics/classifications/current/ns-sec/self-coded/index.html.

- 9.McDonald AS. Profiling for success: reasoning tests user’s guide (version 1.2). Team Focus, 2008 (latest version available at www.profilingforsuccess.com/ReasoningTestUserGuide_update_2010).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix

Web table B

Web table A