Abstract

Sepsis is characterized by a systemic inflammatory response caused by infection, and can result in organ failure and death. Removal of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines from the circulating blood is a promising treatment for severe sepsis. We are developing an extracorporeal hemoadsorption device to remove cytokines from the blood using biocompatible, polymer sorbent beads. In this study, we used confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) to directly examine adsorption dynamics of a cytokine (IL-6) within hemoadsorption beads. Fluorescently labeled IL-6 was incubated with sorbent particles, and CLSM was used to quantify spatial adsorption profiles of IL-6 within the sorbent matrix. IL-6 adsorption was limited to the outer 15μm of the sorbent particle over a relevant clinical time period, and intraparticle adsorption dynamics was modeled using classical adsorption/diffusion mechanisms. A single model parameter, α = qmax K / D, was estimated by fitting CLSM intensity profiles to our mathematical model, where qmax and K are Langmuir adsorption isotherm parameters, and D is the effective diffusion coefficient of IL-6 within the sorbent matrix. Given the large diameter of our sorbent beads (450μm), less than 20% of available sorbent surface area participates in cytokine adsorption. Development of smaller beads may accelerate cytokine adsorption by maximizing available surface area per bead mass.

Keywords: sepsis, adsorption, CLSM, cytokine, blood purification

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is a serious medical condition characterized by systemic inflammation caused by infection, and affects more than 750,000 individuals per year in the US, with a mortality rate of 30%.1 The pathophysiology of sepsis is complex and not entirely understood, but is believed to be related to the activity of multiple interdependent humoral mediator pathways.2 Therapies aimed at blocking single mediators within the network of pathological processes, such as TNF antagonists,3 IL-1 antagonists,4 and anti-endotoxin antibodies,5 have failed to improve clinical outcomes. One promising strategy for the treatment of sepsis is nonspecific removal of inflammatory cytokines from the circulating blood.6 Cytokines are ubiquitous inflammatory mediators in the blood that are substantially up-regulated during the onset of sepsis.7 Elevated levels of circulating cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF are highly associated with increased risk of death.8 Nonspecific removal of both pro-inflammatory (e.g. IL-6, TNF) and anti-inflammatory (e.g. IL-10) cytokines may provide a beneficial clinical effect by promoting overall down-regulation of systemic inflammation, and assisting the body in regaining homeostasis.9

Our group is developing an extracorporeal hemoadsorption device to remove cytokines from circulating blood using a novel, biocompatible, sorbent bead technology (CytoSorb™, CytoSorbents™, Inc.). CytoSorb hemoadsorption beads are polystyrene-divinylbenzene porous particles (450μm avg. particle diameter, 0.8-5nm pore diameter, 850m2/g surface area) with a biocompatible polyvinyl-pyrrolidone coating. Adsorption to the internal pore surface is accomplished by a putative combination of nonspecific hydrophobic interactions, and size exclusion of large molecular weight solutes such as immunoglobulins. Kellum, et al. demonstrated rapid clearance of cytokines (IL-6, IL-10, and TNF) and increased mean survival time in a murine sepsis model using CytoSorb hemoadsorption beads.6 Despite significant cytokine removal in this study, a model analysis performed by our group predicted that cytokine adsorption is limited to the outer ~15μm of the sorbent particle over a clinically relevant time period (4-6 hours).10 Given the large diameter of CytoSorb beads (450μm), this prediction suggested that less than 20% of the sorbent surface area participates in cytokine adsorption.

The goal of this work was to study cytokine adsorption dynamics in CytoSorb hemoadsorption beads using confocal laser scanning microscopy to directly quantify adsorption behavior within single sorbent particles. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM), was first applied to studies of adsorption in sorbent materials by Ljunglöf and Hjorth,11 and provides a powerful tool for direct visualization and quantification of fluorescently labeled proteins adsorbed within sorbent particles. Numerous authors have utilized CLSM to study protein uptake phenomena in packed-bed chromatography sorbents.12-19 Hubbuch, et al.20 provides an extensive review of CLSM as an analytical tool in chromatographic research. In this study, CLSM is used to quantify IL-6 adsorption dynamics in CytoSorb hemoadsorption beads, and to compare intraparticle spatial adsorption profiles to predictions of our previous mathematical model.10 Our application of CLSM differs from previous sorbent CLSM studies in two important aspects: 1) CytoSorb beads are significantly larger than sorbents typically characterized using CLSM (450μm compared to 90μm average particle diameter, respectively);20 and 2) physiological cytokine levels found in human sepsis are significantly smaller than protein concentrations typically used in sorbent applications (pg/ml compared to mg/ml, respectively)6,20. Accordingly, in our study we developed new strategies to minimize signal attenuation within the bead, to study cytokine-fluorophore degree of labeling, and to examine effects of bulk cytokine concentration on adsorption. Our CLSM findings confirm the model prediction that less than 20% of sorbent surface area participates in cytokine adsorption, and suggest that the development of smaller sorbent beads for this application could accelerate cytokine removal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Lyophilized recombinant human IL-6 (MW = 21kD, >95% purity) and DyLight™ 549 fluorescent labeling kits were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL). DyLight 549 is an N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester activated fluorophore (MW = 982Da) that reacts with primary amines on the target protein to form stable, covalent bonds. The DyLight 549 fluorophore has an excitation and emission maxima of 562nm and 576nm, respectively. Bovine serum albumin (MW = 66kD, >96% purity) was used as a negative control, and was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Low molecular weight impurities were eliminated by running BSA (1mg/ml) in 10mM PBS through a Superdex™200 gel permeation column (AKTAexplorer FPLC, GE Healthcare) at 0.1ml/min flow rate. The 66kD major protein component was collected and used for all subsequent BSA fluorescent labeling.

Fluorescent Labeling

Lyophilized recombinant human IL-6 (20μg) was reconstituted in 0.5ml 10mM PBS and fluorescently labeled with the DyLight 549 fluorophore as follows: 15μg dried fluorophore was reconstituted in 100μl 10mM PBS and 8μl 0.67M sodium borate buffer, as recommended by the manufacturer. Reconstituted fluorophore (either 50μl or 5μl) was added to 250μl reconstituted IL-6 in PBS and incubated in the dark for 60min. Unreacted fluorophore was removed using resin spin columns provided by the manufacturer. Protein-fluorophore degree of labeling (DOL) could not be directly measured due to low cytokine concentrations used in this study. The FPLC purified BSA was fluorescently labeled in the same manner as IL-6.

Bead Preparation

CytoSorb hemoadsorption beads were provided by CytoSorbents, Inc. (Monmouth Junction, NJ). CytoSorb beads are polystyrene-divinylbenzene porous particles (450μm avg. particle diameter, 67% porosity, 1.02g/cm3 density, 0.8-5nm pore diameter, 850m2/g surface area) with a biocompatible polyvinyl-pyrrolidone coating. Fluorescently labeled IL-6 was incubated with CytoSorb beads as follows: Labeled IL-6 was diluted in 10mM PBS with BSA (10mg/ml) added as a stabilizing protein, to yield final IL-6 concentrations of approximately 1μg/ml, 0.1μg/ml, and 0.01μg/ml. 1mg CytoSorb bead mass was added to each 1ml aliquot, and samples of each IL-6 concentration were placed on a rocker shielded from light for 2, 5, and 18 hours, at ambient temperature. Labeled BSA was added to 1mg CytoSorb bead mass in 1ml PBS to yield a BSA concentration of approximately 20μg/ml. BSA samples were placed on a rocker shielded from light for 2, 5.5, and 21.5 hours, at ambient temperature. At the end of each incubation time point, beads were removed from the corresponding sample, and manually sliced in half using a thin razor blade. Beads that were sliced exactly or as close to the particle centerline as possible were selected for CLSM analysis. Sliced beads were placed sliced side down on a glass cover slip in a droplet of PBS, and imaged using CLSM, as follows.

Confocal Microscopy

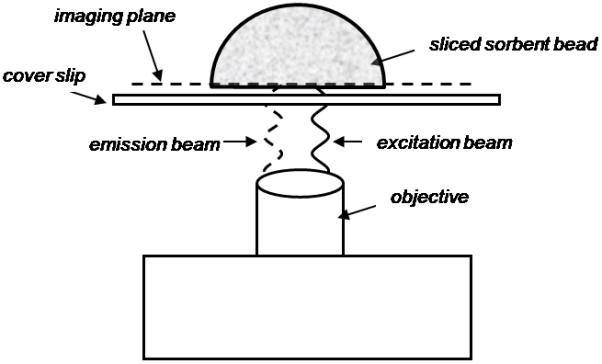

A schematic of the confocal setup with a sliced CytoSorb bead is illustrated in Fig. 1. An Olympus FluoView™ FV1000 confocal microscope outfitted with a UPlanSApo 20X/.75 oil objective and a HeNe laser (543nm excitation, 572nm emission) was used for all confocal imaging. During image capture, the microscope objective was focused such that the confocal plane was localized within the bead, close to the sliced edge to minimize signal loss through the bead. Images were acquired by horizontal scan at 1024×1024 pixel resolution, corresponding to 0.621μm pixel size. Digital images of sliced beads were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health), and intraparticle signal intensity profiles were generated by quantifying a horizontal segment of the image across the diameter of each bead (4 - 5 beads were imaged at each incubation time point). Beads incubated in PBS/BSA buffer without fluorescently labeled IL-6 were sliced and imaged as a control, and background signal was found to be negligible.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of a sliced CytoSorb bead in the confocal microscope setup. The bead is sliced in half using a thin razor blade after incubation with labeled IL-6 or labeled BSA, and placed sliced-face down on a microscope cover slip in a droplet of PBS. The objective lens is focused such that the confocal plane is localized within the particle near the sliced bead edge to minimize signal loss through the bead.

Data Analysis

DiLeo, et al. developed a simple model analysis to study cytokine adsorption dynamics within CytoSorb hemoadsorption beads.10 The model predicts the following intraparticle cytokine adsorption profile:

| (1) |

where q(r,t) is the mass of cytokine adsorbed on the internal pore surface per unit bead mass, qo is the mass of cytokine adsorbed on the particle surface, ρ is the bead mass density, and R is radius of the bead. The model is concentration dependent, where adsorbed cytokine (q) is proportional to free cytokine (c) through the Langmuir adsorption isotherm, . The mathematical model contains one unknown parameter, , where qmax and K are Langmuir adsorption isotherm parameters, and D is the effective diffusion coefficient of the cytokine within the porous bead matrix. In our application, signal intensity generated by fluorescently labeled IL-6 within the sorbent particle is predominantly due to adsorbed rather than free cytokine, due to the large sorbent surface area and low bulk cytokine concentrations. Accordingly, the value of α was estimated at each incubation time point by fitting Eq. 1 to intraparticle IL-6 CLSM fluorescence intensity curves using nonlinear least squares regression in Matlab™, with ρ = 1.02g/cm3. Intraparticle signal intensity profiles for each bead were normalized by dividing the signal intensity value at each pixel by the maximum signal intensity value found at the edge of each bead. Student’s t-test was used to evaluate any statistical differences between the fitted α values.

RESULTS

IL-6 Adsorption Profiles

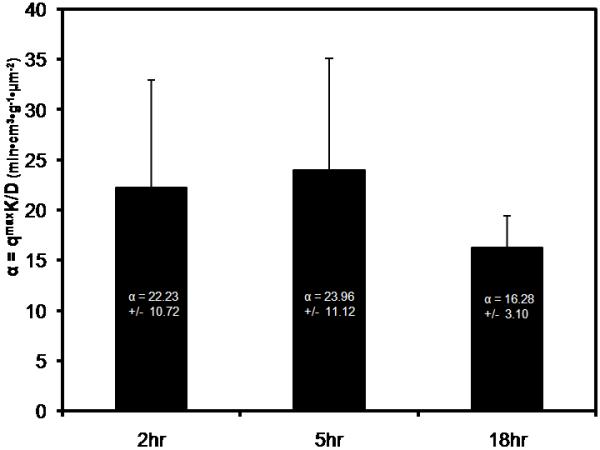

A CLSM image illustrating adsorption of fluorescently labeled IL-6 into a CytoSorb hemoadsorption bead after 5 hours incubation is shown in Fig. 2. IL-6 adsorption is limited to the outer most pores where a thin ring of fluorescence is observed penetrating into the bead from the bead surface. No signal is detected near the center of the particle. Intraparticle intensity profiles for IL-6 at 2hr, 5hr, and 18hr incubation at 1μg/ml are illustrated in Fig. 3(a). Intensity is normalized by the maximum intensity found at the bead surface (Imax), where Imax ~ qo from Eq. 1. Normalized intensity is greatest at the bead surface (I/Imax = 1), and quickly decays as IL-6 diffuses into the sorbent and adsorbs to the pore walls. The protein front slowly moves through the particle over time, yet even after 18hr incubation time, IL-6 does not penetrate farther than 30μm into the bead. Intraparticle intensity profiles for labeled BSA at 2hr, 5.5hr, and 21.5hr incubation are illustrated in Fig. 3(b). In contrast to the behavior observed for IL-6, BSA does not continually penetrate into the bead over time. The mathematical model (Eq. 1) was fit to the IL-6 CLSM curves at each time point, as shown by the solid lines in Fig. 3(a). Good agreement exists between the model fits and the CLSM data (R2 > 0.98 for all fits). Fig. 4 illustrates fitted values for the model parameter α at each time point. The α values were not statistically different between any two IL-6 incubation time points (p > 0.1).

Fig. 2.

CLSM image of a sliced CytoSorb bead after incubation with fluorescently labeled IL-6 for 5 hours. IL-6 adsorption is restricted to the outer most sorbent pores, evident by the thin ring of fluorescence near the bead surface. Intraparticle signal intensity was quantified by horizontal scan of the digital image across the bead diameter.

Fig. 3.

(a) Normalized IL-6 CLSM intraparticle intensity profiles at 2hr, 5hr, and 18hr incubation times with CytoSorb beads. Intensity at each pixel is normalized by the maximum intensity at the bead surface. 4 or 5 beads were imaged at each time point, and signal intensities within the particles were quantified. Signal intensity is greatest at the bead surface, and quickly decays as IL-6 diffuses into the bead and adsorbs to the pore walls. Solid lines indicate corresponding nonlinear regression model fits at each time point. (b) Normalized BSA CLSM intraparticle intensity profiles at 2hr, 5.5hr, and 21.5hr incubation times with CytoSorb beads.

Fig. 4.

Values of the model parameter α were estimated by fitting the mathematical model (Eq. 1) to the IL-6 CLSM intensity profiles at each time point using nonlinear least squares regression. The α values were not statistically different (p > 0.1) for any two incubation time points tested.

Effect of Bulk IL-6 Concentration

Labeled IL-6 concentrations were varied to confirm that normalized adsorption profiles were independent of bulk IL-6 concentration. Fig. 5(a) illustrates intraparticle IL-6 intensity profiles for CytoSorb beads incubated for 5hr with 1μg/ml, 0.1μg/ml, and 0.01μg/ml labeled IL-6. Similar penetration curves were observed for all concentration values tested. Intensity profiles were fit to the mathematical model (Eq. 1), and α was estimated by best fit of the model to the CLSM data (Fig. 5(b)). The α values were not statistically different between any two bulk IL-6 concentrations tested (p > 0.49).

Fig. 5.

(a) Various concentrations of labeled IL-6 (1μg/ml, 0.1μg/ml, 0.01μg/ml) were incubated for 5 hours with CytoSorb beads. Intraparticle intensity curves were quantified, and the model parameter, α, was estimated by best fit of the model to CLSM intensity curves. (b) The α values were not statistically different for any two IL-6 concentrations tested (p > 0.49).

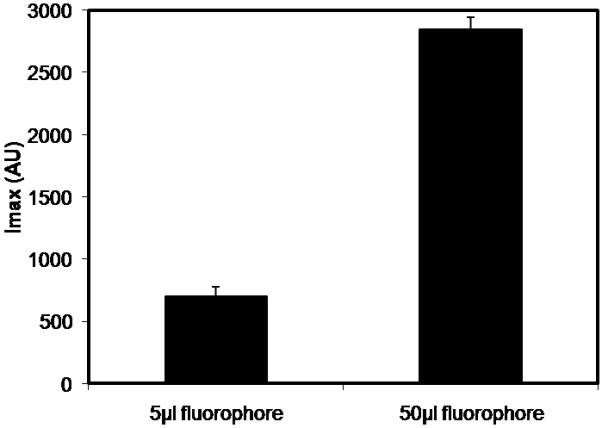

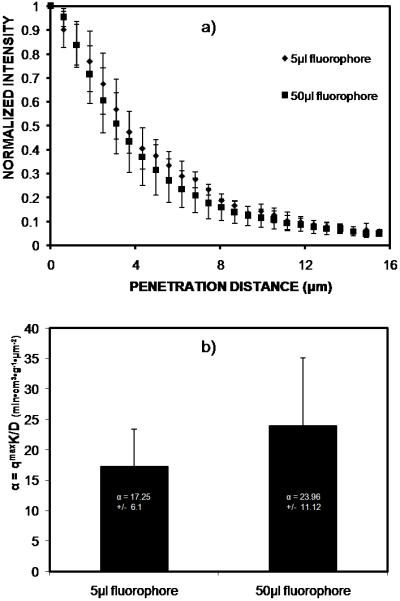

Effect of Label on IL-6 Adsorption

We tested whether the degree of labeling (DOL) affected IL-6 adsorption by reducing the DOL during the fluorophore-cytokine conjugation step. The DOL was decreased by reducing the volume of fluorophore added to IL-6 during conjugation.21 Fig. 6 illustrates the maximum intensity values at the bead surface after 5hr incubation with IL-6 labeled using either 5μl or 50μl fluorophore. Beads incubated with IL-6 conjugated with less fluorophore demonstrated lower maximum intensity values. This indicates a lower DOL for IL-6 samples conjugated with 5μl fluorophore since the same IL-6 concentration and imaging parameters were used for both DOL conditions. As demonstrated in Fig. 7(a), the low DOL (5μl fluorophore) and the high DOL (50μl fluorophore) IL-6 intensity profiles are similar after 5hr incubation. The curves were fit to the mathematical model (Eq. 1) to determine α values (Fig. 7(b)). The α values were not statistically different between the two DOL conditions (p > .25).

Fig. 6.

Comparison of maximum intensity values at the bead surface under different IL-6 labeling conditions. IL-6 was labeled using either 5μl or 50μl reconstituted fluorophore, incubated with CytoSorb beads for 5 hours, and imaged using CLSM. Lower intensity values were observed at the bead surface for the 5μl fluorophore labeling condition.

Fig. 7.

(a) Normalized IL-6 intraparticle intensity profiles for 5μl and 50μl labeling conditions after 5hr incubation with CytoSorb beads. (b) Intraparticle intensity profiles were fit to the mathematical model, and the model parameter, α, was estimated for both IL-6 DOL conditions. The α values were not statistically different (p > .25) between the DOL conditions.

DISCUSSION

Removal of inflammatory cytokines from the circulating blood is a promising treatment for severe sepsis. We are developing an extracorporeal device to remove cytokines through adsorption to a high surface area, biocompatible, porous polymer sorbent (CytoSorb). The goal of this work was to examine the dynamics of cytokine adsorption within single sorbent particles using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). IL-6 adsorption dynamics can be modeled using classical adsorption/diffusion mechanisms, and a single model parameter, , can characterize interactions between IL-6 and CytoSorb beads, where qmax and K are Langmuir adsorption isotherm parameters, and D is the effective diffusion coefficient within the porous matrix. After 5hr incubation with sorbent beads, IL-6 adsorption was limited to the outer 15μm of the pore structure, which represents use of less than 20% of available surface area for adsorption. The CytoSorb pore structure was designed to exclude large molecular weight solutes such as albumin and immunoglobulins. We confirmed that BSA (66kD) does not penetrate appreciably into the sorbent due to size exclusion of BSA from the internal pore structure.

In our previous work in which the mathematical model was developed,10 we fit our model to ex vivo data on cytokine removal from septic rat blood circulated through a hemoadsorption device containing the same CytoSorb beads.22 We have also fit the mathematical model to in vitro studies of cytokine removal from spiked serum circulated through CytoSorb cartridges.23 In these recirculation experiments as opposed to batch incubation experiments performed in this study, the same mathematical model yields a parameter, Γ, given by:

| (2) |

The Langmuir parameters, qmax and K, cannot be practically measured in CytoSorb beads due to the large amount of recombinant cytokine needed. We can estimate, however, an intraparticle IL-6 diffusion coefficient by dividing Γ (Eq. 2) by α, which yields D2. Using Γ = 1.05×10−4 cm2·ml·min−1·g−1 for IL-6 in the in vitro recirculation studies, and α = 20.8 min·cm3·g−1·μm−2 from this study, the IL-6 effective diffusion coefficient is estimated as 3.7×10−9 cm2/s. Assuming a free IL-6 diffusion coefficient of 1.0×10−6 cm2/s and hydrodynamic radius of 2nm from similarly sized molecules,24,25 theoretical hindered diffusion models26-28 predict intraparticle diffusion coefficients within the range of our estimated value, given the approximate pore size of CytoSorb beads (0.8-5nm).

The CLSM technique presented in this paper differs from typical CLSM studies due to the large size of CytoSorb beads, and the low protein concentrations necessary to mimic cytokine levels found in human sepsis. In typical CLSM studies, signal attenuation by the sorbent material is either neglected or corrected using mathematical light attenuation models.18,29 Given the large size of CytoSorb beads compared to other sorbents (450μm vs. 90um, respectively), signal attenuation could not be neglected nor adequately corrected by these attenuation models. Accordingly, we needed to eliminate signal attenuation by slicing the beads in half prior to imaging. Slight variations in sliced bead geometry from the slicing technique may have resulted in variability observed in the CLSM adsorption profiles, however, we would not expect small geometric variations to significantly affect average penetration behavior given the small penetration depths relative to particle diameter. In typical CLSM studies, the steric effect of fluorophore conjugation on protein adsorption is assumed negligible because of large sorbent pore sizes relative to protein size.30 Given the small size of CytoSorb pores compared to other sorbents, we wanted to assess whether steric effects due to fluorophore conjugation might alter cytokine intensity profiles. The DOL could not be measured directly due to low cytokine concentrations used, but we lowered IL-6 DOL by reducing the molar excess of fluorophore during the conjugation step, and demonstrated that IL-6 adsorption was unaffected. This result indicates minimal interference from fluorophore conjugation, and we would expect unlabeled IL-6 to perform in a similar manner.

Typical in vivo IL-6 levels in human sepsis are less than 0.001μg/ml.6 We could not obtain adequate signal to noise levels of intensity at this bulk IL-6 concentration. Theoretically, normalized intensity profiles for IL-6 adsorption should be independent of bulk IL-6 concentration when adsorption is occurring in the linear portion of the Langmuir adsorption isotherm. We found no statistical difference in adsorption behavior as measured by the α parameter for bulk IL-6 concentrations of 1μg/ml, 0.1μg/ml and 0.01μg/ml. Accordingly, the adsorption dynamics of IL-6 at physiological levels is unlikely to differ from that reported here.

CONCLUSIONS

CLSM results indicate that IL-6 adsorption dynamics agree with predictions of our mathematical model, and that IL-6 adsorption is confined to the outer 15μm of the CytoSorb sorbent over a clinically relevant time period. Given this observation, less than 20% of available sorbent surface area is utilized for cytokine adsorption. For the current large size of CytoSorb beads, the surface area for diffusion into the beads relative to bead volume is small for a given mass of beads. Smaller CytoSorb beads may provide significantly faster cytokine capture by maximizing available surface area for diffusion per bead mass. We are currently developing and testing smaller CytoSorb beads to accelerate cytokine capture in a hemoadsorption device. Enhanced removal of cytokines from the circulating blood may improve patient outcomes in severe sepsis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work presented in this publication was made possible by Grant Number R01-HL080926 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH): National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and Public Health Services (PHS) Grant Number 1-T32-HL07612403. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Russell L. Delude for assistance with FPLC, and the Center for Biologic Imaging and the McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh for their support on this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angus D, Linde-Zwirble W, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky M. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: Analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baillie JK. Activated protein C: Controversy and hope in the treatment of sepsis. Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs. 2007;8(11):933–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abraham E, Wunderink R, Silverman H, Perl T, Nasraway S, Levy H, Bone R, Wenzel R, Balk R, Allred R, TNF-α mAb sepsis study group Efficacy and safety of monoclonal antibody to human necrosis factor α in patients with sepsis syndrome. A randomized, controlled, double-blind, multicenter clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc. 1995;273(12):934–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher C, Dhainaut J, Opal S, Pribble J, Balk R, Slotman G, Iberti T, Rackow E, Shapiro M, Greenman R, Phase III rhIL-1ra sepsis syndrome study group Recombinant human interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in the treatment of patients with sepsis syndrome. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 1994;271(23):1836–1843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziegler E, Fisher C, Sprung C, Straube R, Sadoff J, Foulke G, Wortel C, Fink M, Dellinger R, Teng N, The HA-1A sepsis study group Treatment of Gram-negative bacteremia and septic shock with HA-1A human monoclonal antibody against endotoxin. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(7):429–436. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102143240701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kellum JA, Song M, Venkataraman R. Hemoadsorption removes tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-6, and interleukin-10, reduces nuclear factor-KB DNA binding, and improves short-term survival in lethal endotoxemia. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(3):801–805. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114997.39857.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casey LC. Immunologic response to infection and its role in septic shock. Critical Care Clinics. 2000;16(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kellum JA, Kong L, Fink MP, Weissfeld LA, Yealy DM, Pinsky MR, Fine J, Krichevsky A, Delude RL, Angus DC. Understanding the inflammatory cytokine response in pneumonia and sepsis: results of the Genetic and Inflammatory Markers of Sepsis (GenIMS) Study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(15):1655–1663. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venkataraman R, Subramanian S, Kellum JA. Clinical review: Extracorporeal blood purification in severe sepsis. Critical Care. 2003;7:139–145. doi: 10.1186/cc1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiLeo MV, Kellum JA, Federspiel WJ. A simple mathematical model of cytokine capture using a hemoadsorption device. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2009;37(1):222–229. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9587-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ljunglof A, Hjorth R. Confocal microscopy as a tool for studying protein adsorption to chromatographic matrices. Journal of Chromatography A. 1996;743(1):75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubbuch J, Linden T, Knieps E, Ljunglof A, Thommes J, Kula MR. Mechanism and kinetics of protein transport in chromatographic media studied by confocal laser scanning microscopy, Part 1. The interplay of sorbent structure and fluid phase conditions. Journal of Chromatography A. 2003;1021:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2003.08.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ljunglof A, Bergvall P, Bhikhabhai R, Hjorth R. Direct visualisation of plasmid DNA in individual chromatography adsorbent particles by confocal scanning laser microscopy. Journal of Chromatography A. 1999;844(12):129–135. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(99)00386-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou X-P, Li W, Shi Q-H, Sun Y. Analysis of mass transport models for protein adsorption to cation exchanger by visualization with confocal laser scanning microscopy. Journal of Chromatography A. 2006;1103:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ljunglof A, Thommes J. Visualising intraparticle protein transport in porous adsorbents by confocal microscopy. Journal of Chromatography A. 1998;813:387–395. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(98)00378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harinarayan C, Mueller J, Ljunglof A, Fahrner R, Van Alstine J, van Reis R. An exclusion mechanism in ion exchange chromatography. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2006;95(5):775–787. doi: 10.1002/bit.21080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasche V, de Boer M, Lazo C, Gad M. Direct observation of intraparticle equilibration and the rate-limiting step in adsorption of proteins in chromatographic adsorbents with confocal laser scanning microscopy. Journal of Chromatography B. 2003;790:115–129. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(02)02001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang K, Shi Q-H, Sun Y. Modeling and simulation of protein uptake in cation exchanger visualized by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Journal of Chromatography A. 2006;1136:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hubbuch J, Linden T, Knieps E, Thommes J, Kula MR. Dynamics of protein uptake within the adsorbent particle during packed bed chromatography. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2002;80(4):359–368. doi: 10.1002/bit.10500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hubbuch J, Kula MR. Confocal laser scanning microscopy as an analytical tool in chromatographic research. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2008;31:241–259. doi: 10.1007/s00449-008-0197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundberg E, Sundberg M, Graslund T, Uhlen M, Svahn HA. A novel method for reproducible fluorescent labeling of small amounts of antibodies on solid phase. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2007;322:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song M, Winchester J, Albright R, Capponi V, Choquette M, Kellum JA. Cytokine removal with a novel adsorbent polymer. Blood Purification. 2004;22(5):428–434. doi: 10.1159/000080235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiLeo MV, Fisher JD, Federspiel WJ. Experimental validation of a theoretical model of cytokine capture using a hemoadsorption device. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10439-009-9780-4. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schroder M, von Lieres E, Hubbuch J. Direct quantification of intraparticle protein diffusion in chromatographic media. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:1429–1436. doi: 10.1021/jp0542726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma U, Carbeck JD. Hydrodynamic radius ladders of proteins. Electrophoresis. 2005;26(11):2086–2091. doi: 10.1002/elps.200410334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bassingthwaighte JB. A practical extension of hydrodynamic theory of porous transport for hydrophilic solutes. Microcirculation. 2006;13:111–118. doi: 10.1080/10739680500466384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck R, Schultz J. Hindered diffusion in microporous membranes with known pore geometry. Science. 1970;170(3964):1302–1305. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3964.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Renkin EM. Filtration, diffusion, and molecular sieving through porous cellulose membranes. J. Gen. Physiology. 1954;38:225–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Susanto A, Herrmann T, Hubbuch J. Short-cut method for the correction of light attenuation influences in the experimental data obtained from confocal laser scanning microscopy. Journal of Chromatography A. 2006;1136:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linden T, Ljunglof A, Hagel L, Kula MR, Thommes J. Visualizing patterns of protein uptake to porous media using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Separation Science and Technology. 2002;37(1):1–32. [Google Scholar]