Abstract

Objective

To assess the effect of a 40 mg methylprednisolone injection proximal to the carpal tunnel in patients with the carpal tunnel syndrome.

Design

Randomised double blind placebo controlled trial.

Setting

Outpatient neurology clinic in a district general hospital.

Participants

Patients with symptoms of the carpal tunnel syndrome for more than 3 months, confirmed by electrophysiological tests and aged over 18 years.

Intervention

Injection with 10 mg lignocaine (lidocaine) or 10 mg lignocaine and 40 mg methylprednisolone. Non-responders who had received lignocaine received 40 mg methylprednisolone and 10 mg lignocaine and were followed in an open study.

Main outcome measures

Participants were scored as having improved or not improved. Improved was defined as no symptoms or minor symptoms requiring no further treatment.

Results

At 1 month 6 (20%) of 30 patients in the control group had improved compared with 23 (77%) of 30 patients the intervention group (difference 57% (95% confidence interval 36% to 77%)). After 1 year, 2 of 6 improved patients in the control group did not need a second treatment, compared with 15 of 23 improved patients in the intervention group (difference 43% (23% to 63%). Of the 28 non-responders in the control group, 24 (86%) improved after methylprednisolone. Of these 24 patients, 12 needed surgical treatment within one year.

Conclusion

A single injection with steroids close to the carpal tunnel may result in long term improvement and should be considered before surgical decompression.

Key messages

Corticosteroid injections into the carpal tunnel may damage the nerve, and any treatment benefits may be of short duration

A single injection with steroids proximal to the carpal tunnel improves 77% of patients with the carpal tunnel syndrome at one month after treatment

This single injection is still effective at one year in half of the patients

Injections proximal to the carpal tunnel have no side effects and are easier to carry out than injections into the carpal tunnel

Introduction

The carpal tunnel syndrome is caused by compression of the median nerve at the wrist and is a common cause of pain in the arm, particularly in women. Injection with corticosteroids is one of the many recommended treatments.1

One of the techniques for such injection entails injection just proximal to (not into) the carpal tunnel. The rationale for this injection site is that there is often a swelling at the volar side of the forearm, close to the carpal tunnel, which might contribute to compression of the median nerve.2Moreover, the risk of damaging the median nerve by injection at this site is lower than by injection into the narrow carpal tunnel. The rationale for using lignocaine (lidocaine) together with corticosteroids is twofold: the injection is painless, and diminished sensation afterwards shows that the injection was properly carried out.

We investigated in a double blind randomised trial, firstly, whether symptoms disappeared after injection with corticosteroids proximal to the carpal tunnel and, secondly, how many patients remained free of symptoms at follow up after this treatment.

Participants and methods

Participants

The participants were patients referred to the Medical Centre Alkmaar with signs and symptoms of the carpal tunnel syndrome of more than 3 months’ duration confirmed by electrophysiological tests. In those with bilateral symptoms, the arm with the most severe symptoms was chosen, and treatment of this arm was randomised. We excluded patients aged under 18 years or patients who had already been treated for symptoms of the carpal tunnel syndrome.

The trial was approved by the medical centre’s ethics committee. Patients gave written informed consent. The ethics committee required an interim analysis after inclusion of half of all participants.

Intervention

The injections were given by one neurologist (JWHHD). They contained 10 mg lignocaine or 10 mg lignocaine and 40 mg methylprednisolone. The site of injection was at the volar side of the forearm 4 cm proximal to the wrist crease between the tendons of the radial flexor muscle and the long palmar muscle. Injections were given with a 3 cm long 0.7 mm needle fig 1).The angle of introduction of the needle depended on the size of the wrist. In participants with a thin wrist the median nerve is close to the skin. In these participants the angle was 10°. The angle was larger, about 20°, in those with a thick wrist. In participants with well developed muscles, the pronator quadratus muscle may push up the median nerve, so in a thick muscular arm the angle of introduction was also flat, between 10° and 20°. The needle was introduced slowly, and the participant was instructed to say stop if he or she felt pins and needles or pain in the fingers. If a resistance was felt the needle was withdrawn a few millimetres then repositioned. The injection was given without much pressure. After injection, the 1 ml fluid bolus was gently massaged towards the carpal tunnel.

Figure 1.

Site for injecting corticosteroid to treat carpal tunnel syndrome

Outcome

One month after injection the randomised participants visited the outpatient department and were asked by another neurologist (MMV) whether they had no symptoms or only minor symptoms that they considered so much improved that they felt no further treatment was necessary. Further visits were planned for 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after the injection or earlier if the participant felt this was necessary. At these visits, participants were asked the same question. If treatment was necessary the decision to treat was taken first, and then the trial code was broken. If a patient had not been treated with methylprednisolone this treatment was offered, otherwise surgical decompression was performed.

Assignment and blinding

Using a random number table, the hospital pharmacist prepared the trial drug in blocks of 20. The syringes for injection were sent from the pharmacy to the outpatient department, where it was impossible to distinguish the syringes containing methylprednisolone plus lignocaine from those containing lignocaine as paper was glued around the syringes. To further ensure blinding, the assessments were carried out by another neurologist (MMV). Neither the doctor nor the participant, therefore, knew what treatment was given. The doctors and participants remained blind to treatment during the assessments at follow up.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on the assumption that after 1 month 80% of the participants in the intervention group would respond to treatment versus 50% in the control group. With a power of 80% and a significance level of 5% two sided, this meant that at least 80 participants needed to be included.

Analysis

We used χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests to compare differences between the groups. We calculated the 95% confidence intervals of the differences of the proportion of participants who responded to treatment.

Results

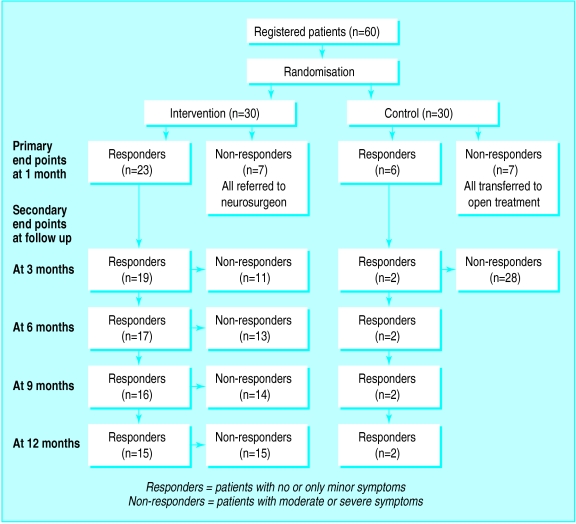

After the ethics committee had seen the results of the interim analysis (after 40 participants had been recruited) it withdrew permission for further randomisation. Meanwhile a further 20 participants had entered the study. The final analysis of the results is on all 60 randomised patients. None of the participants was lost at follow up. Figure 2 shows the participant flow.

Figure 2.

Participant flow

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics. No significant differences existed between the groups. After 1 month 23 of the 30 participants in the intervention group had no or only minor symptoms versus 6 of the 30 participants in the control group (P<0.001). Table 2 shows the proportion of participants not needing a second treatment. At all time intervals the number of participants not requiring treatment was significantly higher in the intervention group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 60 participants in trial

| Variable | Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|

| No of participants | 30 | 30 |

| Mean age (years) | 53 | 51 |

| No of females | 24 | 26 |

| No of participants with pain in arm at night | 27 | 26 |

| No of participants with swelling near carpal tunnel | 19 | 26 |

| Average duration of symptoms (months) | 32 | 25 |

| No of participants with absence of sensory action potential of median nerve | 25 | 23 |

Table 2.

Treatment response at follow up

| Period after treatment | No (%) of participants not needing second treatment

|

% observed difference (95% confidence interval of difference) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group (n=30) | Control group (n=30) | ||

| 1 month | 23 (77) | 6 (20) | 57 (36 to 77) |

| 3 months | 19 (63) | 2 (7) | 56 (37 to 76) |

| 6 months | 17 (57) | 2 (7) | 50 (30 to 70) |

| 9 months | 16 (53) | 2 (7) | 46 (27 to 67) |

| 12 months | 15 (50) | 2 (7) | 43 (23 to 63) |

In the open phase of the study 24 of 28 participants in the control group responded to treatment with methylprednisolone. Of this group, 12 of 24 participants needed a third treatment (surgery), performed on average 3.4 months after the second treatment. There were no side effects.

Discussion

This study confirmed a beneficial effect of injection with methylprednisolone near the carpal tunnel. In the centre where this study was performed, neurologists have for 20 years been injecting methylprednisolone close to, but not in, the carpal tunnel. The neurologists claimed not only excellent results in the short term but also long lasting improvements. The duration of improvement shown in this double blind controlled study seemed to be longer than has been reported in other studies.3–8 Two studies were clinical trials.7,8 In the first trial, injections with steroids into the carpal tunnel were compared with intramuscular injections. At the end of one month significant improvement was seen in the group of 18 patients who had been given injections into the carpal tunnel, but this beneficial effect had disappeared after 10-12 months. In the second trial methylprednisolone was injected locally, and again the effect of treatment was of short duration.

Our rationale for positioning injections close to the carpal tunnel was that injections at this site are less likely to damage the nerve and are easier to carry out than injections into the carpal tunnel. Another reason that this site was chosen was the common occurrence of a swelling close to the carpal tunnel—in this study in three quarters of the participants. Such a swelling probably consists of fat tissue and hypertrophy of the pronator quadratus muscle. A locally applied injection may reduce the swelling by the lipolytic action of methylprednisolone, which would explain the long term beneficial effect. Whether this is true, this treatment is safe and is easier to carry out than surgical decompression or 20 sessions of ultrasound treatment.9

Acknowledgments

We thank J Prins of the hospital’s pharmacy for preparing the syringes.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practise parameter for carpal tunnel syndrome. Neurology. 1993;43:2406–2409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton RI. Carpal tunnel syndrome [book review] Arch Neurol. 1994;51:641–642. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green DP. Diagnostic and therapeutic value of carpal tunnel injection. J Hand Surg. 1984;9A:850–854. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(84)80065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phalen GS. The carpal tunnel syndrome: clinical evaluation of 598 hands. Clin Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1972;83:29–40. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197203000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wood MR. Hydrocortisone injections for carpal tunnel syndrome. Hand. 1980;12:62–64. doi: 10.1016/s0072-968x(80)80031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irwin LR, Beckett R, Suman RK. Steroid injection for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg. 1996;21:355–357. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(05)80202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozdogan H, Yazici H. The efficacy of local steroid injections in idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome: a double blind study. Br J Rheumatol. 1984;23:272–275. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/23.4.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girlanda P, Dattola R, Venuto C, Mangiapane R, Nicolosi C, Messina C. Local steroid treatment in idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome: short and long term efficacy. J Neurol. 1993;240:187–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00857526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebenbichler GR, Resch KL, Wiesinger GF, Uhl F, Ghanem A-H, Fialka V. Ultrasound treatment for treating the carpal tunnel syndrome: randomised “sham” controlled trial. BMJ. 1998;316:731–735. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7133.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]