Abstract

Gastroduodenal disease is more common among adults and children with cagA+ H. pylori infection, but disease severity varies among those infected with cagA+ strains. We examined whether cagA in situ expression can predict disease manifestations among H. pylori infected children. Fifty-one children were selected from 805 patients with abdominal symptoms who underwent esophago-gastroduodenoscopy with gastric biopsies. Endoscopic and histologic gastritis were scored and H. pylori colonization was quantified by Genta stain and in situ hybridization expression of 16S rRNA and cagA. Endoscopy was either normal (n=14) or demonstrated nodularity (n=18), gastric ulcer (GU, n=8) or duodenal ulcer (DU, n=11). H. pylori was present in 7, 18, 6, and 10 children, respectively. Expression of 16S rRNA and cagA were significantly higher in children with ulcer compared to normal. The fraction of H. pylori bacteria expressing cagA in situ was higher in children with ulcer compared to those with endoscopic nodularity (p<0.05). Thus, cagA in situ expression is increased in H. pylori infected children with peptic ulcers and may play a role in the pathogenesis of peptic ulcer disease during childhood. Determination of in situ expression of cagA complements traditional isolation and in vitro testing of single colony isolates.

Keywords: H. pylori, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, nodularity, gastritis, cagA gene expression, virulence factor

INTRODUCTION

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is strongly associated with H. pylori infection in adults and in children.1, 2 Of note, virtually all infected subjects have various degrees of gastritis but only 10% of H. pylori positive individuals develop PUD. This observation is attributed to a combination of environmental factors, host predisposition, H. pylori density, and the virulence of some H. pylori strains.3–6

The virulence factor that has received the most attention is the cytotoxin-associated gene A (cagA), which encodes the CagA protein and is implicated in the increased risk of PUD. CagA is translocated into the host cell, where it is phosphorylated, binds to SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase, leading to cytokine production by the host cell, phosphorylation-dependent cytoskeletal rearrangement, and transcriptional activation of host’s targets.7 The cellular effects of CagA may explain why patients infected with CagA+ strains usually have a higher inflammatory response and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.4, 8, 9 In turn, these gastric mucosal responses induce peptic ulcer disease (PUD), precancerous lesions and cancer in adults.1 The CagA protein also represents a marker for a genomic fragment called the cag-pathogenicity associated island (cag PAI), which encodes at least 27 proteins that are believed to have pathogenic properties.10

CagA is strongly immunogenic and high antibody titers are present in subjects infected by cagA+ strains. As a result, measuring plasma concentrations of anti-CagA IgG by ELISA has allowed testing for cagA+ infection in large epidemiological studies.11 The ELISA method or direct PCR characterization of the strains isolated from children demonstrated a significant association between cagA+ H. pylori infections and PUD in children,12–15 although the association did not reach a level of statistical significance in some studies.16, 17 The cause of this variability is unknown, but may be related to differences in methodology, study populations, and/or bacterial strains.7

Here, we explored the possibility that in situ cagA expression is a critical determinant of disease outcome, i.e. inflammation or serious mucosal damage and PUD. To test this hypothesis, we used an in situ hybridization approach to quantify the expression of H. pylori 16S rRNA and cagA in the gastric mucosa of children with normal endoscopies, nodularity, gastric ulcer (GU), or duodenal ulcer (DU). We observed that bacterial density was increased in patients with GU and DU compared to children with normal endoscopy and that the fraction of H. pylori bacteria expressing cagA was increased in children with PUD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population and treatment

During a 4-year period, 805 children underwent diagnostic upper endoscopy procedure in the Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Walter Reed Army Medical Center. A review of these 805 procedures showed that 41 cases had PUD and/or were H. pylori positive by CLO test and/or ELISA. Four of the H. pylori positive subjects had normal endoscopy. To increase the sample size in the normal endoscopy group and improve statistical power for comparisons among groups as defined by endoscopic findings, we then selected the 10 most recently endoscoped children who were age-matched, had no esophageal or gastroduodenal endoscopic abnormality, and were H. pylori negative by CLO test and H&E stains, plus ELISA if available. None of the patients had had burns or head injury.

Mean age was 12.2 years (range: 3 to 18), 61% were male, and ethnic distribution included 53% Caucasians, 27% African-Americans, 14% Hispanics, and 6% Asians. The indications for endoscopy included abdominal pain (n=38, 74%), nausea and vomiting (n=33, 65%), upper gastrointestinal bleeding (n=8, 16%), weight loss (n=4, 8%) and heartburn (n=8, 16%). One patient was asymptomatic and evaluation was prompted by intrafamilial H. pylori infection and positive serology.

Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopies

After obtaining informed consent, patients underwent diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy under conscious sedation or general anesthesia. At least two antral biopsies were obtained. Endoscopic findings were graded by reviewing the reports and photographs by a single investigator (JRR) and scored as normal, antral nodularity, gastric ulcer, or duodenal ulcer. Ulcers were 2–4 mm diameter single ulcers, but the exact size of each ulcer was not recorded. Following the endoscopy, all H. pylori infected patients received a triple therapy consisting of omeprazole (1 mg/kg), amoxicillin (40 mg/kg) and clarithromycin (10 mg/kg) twice a day for 10 days. Metronidazole was substituted for amoxicillin in allergic patients. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of Walter Reed Army Medical Center and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

Histology

Archived antral biopsies from these 51 children were serially sectioned (5μm) and H&E-stained, Genta-stained,18 and processed for fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). The FISH method is highly specific for H. pylori 16S rRNA as it uses a probe (biotin-labeled 5′-TACCTCT CCCACACTCT AGAATAGTAGT TTCAAATGC-3′) that is 100% homologous with over 150 H. pylori strains published in the GenBank database.19 Similarly, the FISH cagA probe (5′-CTG CAA AAG ATT GTT TGG CAG A-3′-NH2 digoxigenin labeled)20 completely matched the cagA sequence of 128 H. pylori strains published in the GenBank database, with only one mismatch between the probe and the cagA sequence of 34 additional strains. FISH can detect a sequence that is different from the probe by one bp, and our data strongly indicate that we can detect the vast majority of H. pylori strains that express cagA.20 The Genta silver stain method clearly outlines the presence of H. pylori, but it is not specific for this bacterium as it identifies virtually all Gram positive and negative bacteria, as well as fungi, many viral inclusions (e.g. cytomegalovirus) and parasites in larvae stage.

Chronic and acute inflammation and H. pylori density were scored according to the Updated Sydney System.21 A pediatric pathologist (ERP) blinded to the endoscopy, Genta, and FISH results performed the histologic assessment of gastritis.

Genta and FISH quantification.19

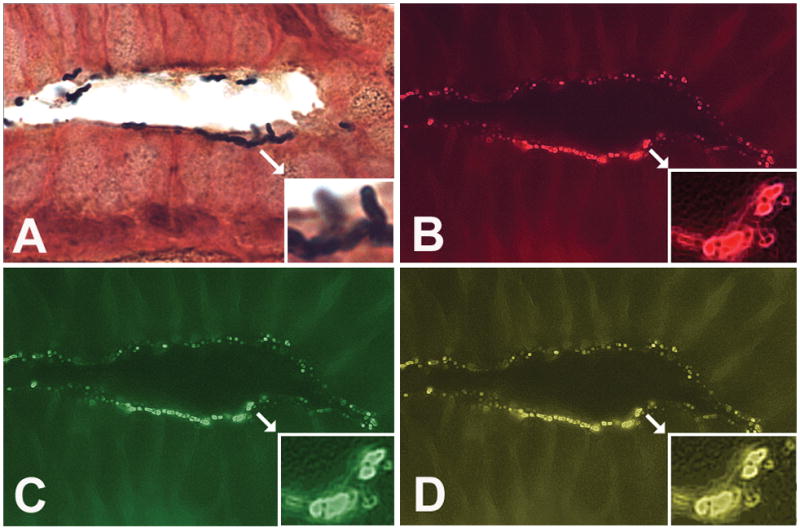

In brief, an Eclipse E800 Nikon microscope was used to examine the sections at 100X, 400X and 1000X. Morphometric quantification of H. pylori and gene expression was performed with fluorescence at 400X using an intraocular 27-mm grid (Klarmann Rulings, Inc.) and a fully functional super high pressure mercury lamp (Hg100W) (Ushio Electric Inc.) as reported.19, 20 Bacterial density was counted without knowledge of the clinical diagnosis or endoscopic appearance and using constant fluorescence exposure. Isolated bacteria and clusters visualized in the lumen of the stomach and gastric glands were counted. Bacteria with characteristic morphology of H. pylori after Genta, 16S rRNA expression (red fluorescence by avidin Texas red, TR), cagA expression (green fluorescence per by avidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate, FITC), and co-localization of 16S rRNA and cagA (yellow fluorescence), corresponding to merged pictures, were observed and quantified at 400X (Figure 1). Three randomly selected fields of view were counted and the number of bacteria or clusters of bacteria per 104 μm3 (i.e. per 50-μmby 40-μm region of a 5-μm-thick formalin-fixed section) was calculated (means ± SEM). 19 The expression of cagA relative to 16S rRNA expression was calculated as the quotient of these two parameters. Positive, negative, and non specific binding controls were performed as described.20 In addition, images were digitized using a charge-coupled device color camera (model HV-C20C20M; Hitachi) interfaced with a Sun X-20 workstation. Of note, Genta-stain quantification gives a general quantification of bacterial infection whereas in situ-hybridization is specific for H. pylori genes.

Figure 1. H. pylori colonization in the antral gland of a child with duodenal ulcer in two successive 5-μm-thick serial sections (Original magnification ×1000). A is a picture of the first serial section and B, C, and D are three pictures of the second serial section with three different epi-fluorescence filters. Because the two serial sections are 5-μm apart, the H. pylori observed in A are not the same as the ones observed in B, C, and D, whereas B, C, and D represent different pictures of the same bacteria. Corresponding inserts show higher magnification of bacterial clusters (white arrows).

A. Genta stain of a gastric gland, first serial section; insert: H. pylori colony adherent to superficial epithelial cells.

B, C, and D: FISH of second serial section illustrating 16S rRNA expression (red fluorescence) (B); cagA expression (green fluorescence) (C); and merge of pictures B and C showing co-localization of 16S rRNA and cagA (yellow fluorescence, multiband filter) (D).

H. pylori positivity

Among the 51 children, 41 patients were found to be H. pylori positive by Genta stain and/or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) (see below). Three of them were from the group of 10 children with normal endoscopy who tested H. pylori negative by CLO and H&E and were found to be H. pylori positive by Genta stain and/or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

Data Analysis

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) analysis was used to determine the overall significance of differences between groups; if significant differences were present, then post-hoc Tukey’s tests were was performed. The first ANOVA model included all subjects regardless of H. pylori status, in order to describe the association between endoscopy findings and gastritis in a general population of children receiving diagnostic upper endoscopies. A second ANOVA excluded H. pylori negative subjects, none of whom had gastritis, in order to explore whether any associations identified in the first ANOVA model could be explained by differences in H. pylori infection in the different groups.

Pearson’s r was used to assess correlation between inflammatory indices, bacterial colonization and cagA gene expression. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the prevalence of intestinal metaplasia in the different groups; p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Endoscopy findings and H. pylori status

Children were grouped according to findings at endoscopy (Table 1). The age, gender, ethnicity, and subjective symptoms of the patients were not significantly different among the endoscopic groups.

Table 1.

Demographics, histology grading, and H. pylori prevalence in all patients.

| Normal (n=14) | Nodularity (n=18) | GU (n=8) | DU (n=11) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age [years (range)] | 13.1 (10–17) | 12 (4–17) | 10.4 (3–17) | 12.7 (8.5–17) |

| Males [N (%)] | 7 (50) | 10 (53) | 5 (63) | 9 (82) |

| H. pylori positive [N (%)] | 7 (50) | 18 (100) | 6(75) | 10(91) |

| Acute Gastritis scores | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.3 a | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.4 |

| Chronic Gastritis scores | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.2 a | 1.3 ± 0.4 b | 2.2 ± 0.3 |

p<0.05 vs normal H. pylori negative and

p<0.05 vs Nodularity using ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s tests.

Histopathology (Figures 1 and 2)

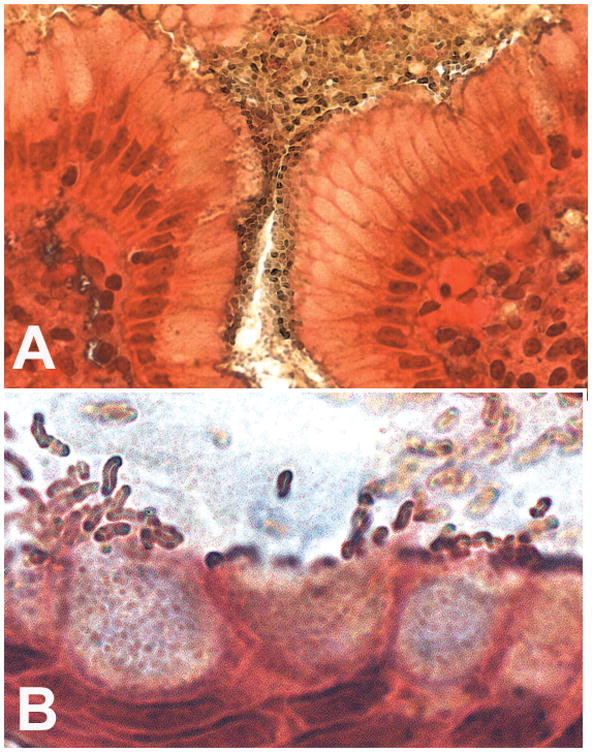

Figure 2. Genta stained paraffin sections of a patient with duodenal ulcer (Original magnification ×1,000).

A. Illustration of the presence of dense colonies in the adherent mucus that covers the superficial mucosa of the antral lumen and foveola.

B. Enlargement detail of an antral gland, illustrating the presence of H. pylori colonizing the mucus with characteristic denser colonies at an intercellular junction on the left of the picture; note that H. pylori density overlying each cell is higher near the tallest epithelial cells, when the mucus is being released, and that some H. pylori are adjacent to mucus secretory granules while other bacteria congregate at the apex of the cells.

Clusters of H. pylori were observed by Genta stain and FISH in 7/14 children with normal endoscopies, in 18/18 children with nodularity, in 10/11 DU and in 6/8 GU. Bacteria were adherent to the foveolar and epithelial surface of antrum, with occasional localization in superficial tortuous pits, outlining the contour of the convoluted surfaces of the epithelial cells. Some H. pylori were in close association with the apical part of columnar mucus secreting cells, in the areas where mucigen secretory granules are released by exocytosis. Bacteria were also abundant in the lumen of dilated pits.

Among all 51 children, acute gastritis scores were significantly higher (p <0.05) in patients with nodularity compared to those with normal endoscopy but not compared to children with GU and DU. In addition, chronic gastritis scores were significantly higher in children with nodularity compared to those with normal endoscopy and GU, but not compared to those with DU (Table 1). In order to study the effect of H. pylori density and cagA expression on endoscopic appearance and gastritis, we then calculated gastritis scores only in H. pylori infected children (Table 2). We observed that chronic and acute gastritis scores were not significantly different among the groups, although acute gastritis scores were twice as high in patients with nodularity, GU, and DU compared to those with normal endoscopy.

Table 2.

Gastritis scores and H. pylori density in H. pylori positive children

| Endoscopic diagnosis | Normal (n=7) | Nodularity (n=18) | GU (n=6) | DU (n=10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Gastritis scores | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

| Chronic Gastritis scores | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.2 |

| Genta (N/104 μm3) | 5.2 ± 1.0 | 11.3 ± 1.4 a | 11.3 ± 1.9 | 12.8 ± 1.2 a |

| 16S rRNA (N/104 μm3) | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 8.4 ± 1.2 | 11.0 ± 2.1 a | 10.6 ± 2.3 a |

| cagA+ (N/104 μm3) | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 8.2 ± 1.6 a | 7.9 ± 1.3 a,b |

| CagA− (N/104 μm3) | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.6 a | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.2 |

| % cagA+ strains | 57.7 ± 6.1 | 45.2 ± 3.6 | 74.1 ± 2.6 b | 70.9 ± 4.3 b |

p <0.05 vs. normal group and

p <0.05 vs. nodularity group, using ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s tests.

Quantification of bacterial density in H. pylori infected children (Table 2)

Densities of H. pylori and cagA+ expression by FISH were significantly higher in the patients with GU and DU compared to H. pylori infected patients with normal endoscopy. In addition, the density of cagA+ bacteria in patients with nodularity was twice as high than in those with normal endoscopy (N.S.) and four times higher in those PUD (p <0.05). Interestingly, the proportion of H. pylori expressing cagA was significantly higher in the GU and DU groups compared to the nodularity group, thus suggesting that PUD is more likely to appear in children infected by H. pylori with higher level of in situ cagA expression. Acute and chronic gastritis positively and significantly (P <0.05) correlated with bacterial density by Genta (r =0.64 and 0.56, respectively), 16S rRNA expression (r =0.64 and 0.51) and cagA expression (r =0.45 and 0.33).

Discussion

The major finding of the present study is that in situ transcription of 16S rRNA and cagA is significantly increased in children with DU and GU compared to those with normal endoscopy and to those with endoscopic nodularity. In addition, a significantly greater proportion of H. pylori colonizing the stomach mucosa of children with PUD express cagA in situ compared to those with nodularity (table 2; p <0.05), similar to our earlier observation in adult patients with gastric adenocarcinoma compared to controls.20 Finally, both acute and chronic gastritis directly correlated with in situ cagA expression (p <0.05) as previously reported with gastric H. pylori density assessed by quantitative culture and histology.4 These findings suggest that the relative fraction of H. pylori strains expressing cagA in situ determine in part whether a child develops PUD or not, although it has no significant effect on histologic gastritis. If these observations are confirmed Therefore, the test could be used to potentially predict the likelihood that a given patient has a higher risk of developing PUD and its complications, and it would justify verification of H. pylori eradication following antibiotic treatment in those patients. However, establishment of a cutoff indicating that an ulcer is present does requires a larger study. In addition, such a study should include a follow-up of children with normal endoscopy to determine whether carriage of strains with high % cagA+ H. pylori increases the ulcer risk, even if no ulcer is present at the time the biopsy was taken.

Importantly, these observations reflect in situ transcription of the cagA gene at the site of mucosal damage, an effect that is present only if the colonizing strain carries the cagA gene. Therefore, the present findings are in agreement with most studies showing that the risk of developing PUD is higher in pediatric and adult patients who are CagA seropositive or carry CagA+ strains.14, 15, 22, 23 They also agree with earlier observations made in adults with PUD using quantitative cultures and quantitative PCR.4, 24

Our observations may also help to reconcile the absence of statistical association between PUD and carriage of cagA positive strains in two other studies16, 25 since in vitro testing for the presence of cagA in isolates may underestimate in vivo transcription as shown for the expression of iceA1 and vacA virulence genes in biopsies of patients.26 Similarly, transcription of cagA was increased in gastric biopsies harvested 10 days after inoculation of a H. pylori strain to Mongolian gerbils compared to in vitro testing of cultured isolates, and this increase appeared to be related to exposure to low pH.27 The latter observation is of prominent relevance to cagA transcription in patients with DU since hyperacidity is a hallmark of duodenal ulcer disease. Because the multiple host and bacterial factors that determine the final outcome of H. pylori infection are known to vary in different populations, we propose that the direct determination of cagA transcription in situ provides a measurement of the combined effect of these factors in each of the patients being studied.

Another important observation made in the present study is that the fraction of H. pylori expressing cagA in situ was significantly higher in the group with PUD than in those with nodularity, although the absolute bacterial density was similar in the two groups (Table 2). Nodular gastritis is frequent in infected children and exceptional in uninfected individuals.17 The finding that cagA is expressed by a greater proportion of the H. pylori that colonize the stomach of children with PUD compared to those with nodular gastritis is relevant since cagA-positive H. pylori have been found to induce higher levels of DNA degradation than cagA-negative mutants in vitro,28 and a relative increase in CagA expression may be responsible in part for defective repair in the gastroduodenal mucosa. However, the observation that the % of cagA+ strains was not significantly different in the normal and nodularity groups suggests that nodularity, in contrast to PUD, is not related to the % of cagA+ H. pylori.

Unexpectedly, three of the normal controls were found to be H. pylori positive by Genta and in situ hybridization despite the fact that CLO and H&E had been negative. This observation suggests that the sensitivity of usual H. pylori testing may be insufficient in pediatric gastroenterology..

One limitation of the present study was its retrospective nature, and the fact that frozen biopsies were not available for corroboration of in situ findings with quantitative RT-PCR to measure cagA RNA expression and/or with in vitro isolation and culture of colonizing H. pylori strains. We propose that these disadvantages are compensated for by the fact that the present approach can be used in archival material and that endoscopic observations, pathological analysis, and determination of H. pylori and cagA density were made by three different observers who were uninformed of the findings made by the other participants in the study.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that the in situ cagA gene expression is increased in H. pylori positive children with gastric and duodenal ulcer, which may play an important role in the pathogenesis of H. pylori related peptic ulcer during childhood. The present observations may help understand why only a fraction of CagA+ patients have DU, since patients who are cagA positive by PCR may have a relatively low expression level of the virulence gene in situ. These results are also consistent with the in vivo finding of genetic divergence between subclones of H. pylori and observations that most patients are infected by both cagA+ and cagA− strains.29 We propose that the in situ approach is a relatively simple and inexpensive method that provides novel information on in vivo transcription of H. pylori virulence genes and thereby may complement the information provided by serology studies and traditional isolation and in vitro testing of single colony isolates. As such, the present results extend our understanding of PUD pathogenesis by demonstrating the importance of cagA expression at the cellular level. If such observations are confirmed, they could be used in clinical practice and permit identification of patients who need post-treatment control of H. pylori eradication and verification that in situ cagA expression is abolished.

Abbreviations

- H. pylori

Helicobacter pylori

- cagA

cytotoxin associated gene A

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- PUD

peptic ulcer disease

- DU

duodenal ulcer

- GU

gastric ulcer

Footnotes

No potential, perceived, or real conflict of interest exist

• JR and MG designed and performed the study, analyzed the data and revised the manuscript; CSM mentored JR and MG, supervised performance and analysis of in situ hybridization studies, and revised the manuscript; HL designed and validated the probes used for in situ hybridization studies, and revised the manuscript; CO performed the statistical analysis and revised the manuscript; ERP reviewed and graded histopathology sections and revised the manuscript; CS helped in the analysis of the clinical data and revised the manuscript; and AD closely supervised and participated in the design and performance of all the steps of the study, and revised the manuscript.

The comments and opinions stated in this manuscript are solely those of the authors and in no way reflect those of the Department of Defense, United States Government, United States Army or the United States Air Force. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of WRAMC and of USUHS. Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (CA82312) and USUHS (CO86EN-01).

Reference List

- 1.Atherton JC. The pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastro-duodenal diseases. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:63–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherman P, Czinn S, Drumm B, Gottrand F, Kawakami E, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in children and adolescents: Working Group Report of the First World Congress of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35:S128–S133. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200208002-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go MF, Graham DY. How does Helicobacter pylori cause duodenal ulcer disease: the bug, the host, or both? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;9 (Suppl 1):S8–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1994.tb01294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atherton JC, Tham KT, Peek RM, Jr, Cover TL. Density of Helicobacter pylori infection in vivo as assessed by quantitative culture and histology. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:552–556. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.3.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamaoka Y, Kodama T, Kita M, Imanishi J, Kashima K, et al. Relation between clinical presentation, Helicobacter pylori density, interleukin 1 β and 8 production, and cagA status. Gut. 1999;45:804–811. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.6.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serrano C, Diaz MI, Valdivia A, Godoy A, Pena A, et al. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori virulence factors and regulatory cytokines as predictors of clinical outcome. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatakeyama M, Higashi H. Helicobacter pylori CagA: a new paradigm for bacterial carcinogenesis. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:835–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00130.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamaoka Y, Kita M, Kodama T, Sawai N, Imanishi J. Helicobacter pylori cagA gene and expression of cytokine messenger RNA in gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1744–1752. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8964399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hida N, Shimoyama T, Jr, Neville P, Dixon MF, Axon AT, et al. Increased expression of IL-10 and IL-12 (p40) mRNA in Helicobacter pylori infected gastric mucosa: relation to bacterial cag status and peptic ulceration. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:658–664. doi: 10.1136/jcp.52.9.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akopyants NS, Clifton SW, Kersulyte D, Crabtree JE, Youree BE, et al. The cag pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori. Molec Microbiol. 1998;28:37–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nomura AM, Perez-Perez GI, Lee J, Stemmermann G, Blaser MJ. Relation between Helicobacter pylori cagA status and risk of peptic ulcer disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:1054–1059. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.11.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husson MO, Gottrand F, Vachee A, Dhaenens L, de la Salle EM, et al. Importance in diagnosis of gastritis of detection by PCR of the cagA gene in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from children. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3300–3303. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3300-3303.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alarcon T, Martinez MJ, Urruzuno P, Cilleruelo ML, Madruga D, et al. Prevalence of CagA and VacA antibodies in children with Helicobacter pylori-associated peptic ulcer compared to prevalence in pediatric patients with active or nonactive chronic gastritis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:842–844. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.5.842-844.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Queiroz DM, Mendes EN, Carvalho AS, Rocha GA, Oliveira AM, et al. Factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection by a cagA-positive strain in children. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:626–630. doi: 10.1086/315262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yahav J, Fradkin A, Weisselberg B, ver-Haver A, Shmuely H, et al. Relevance of CagA positivity to clinical course of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3534–3537. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.10.3534-3537.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold BD, Van Doorn LJ, Guarner J, Owens M, Pierce-Smith D, et al. Genotypic, clinical, and demographic characteristics of children infected with Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1348–1352. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.4.1348-1352.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato S, Nishino Y, Ozawa K, Konno M, Maisawa S, et al. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Japanese children with gastritis or peptic ulcer disease. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:734–738. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1381-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Genta RM, Robason GO, Graham DY. Simultaneous visualization of Helicobacter pylori and gastric morphology: A new stain. Human Pathology. 1994;25:221–226. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(94)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu H, Rahman A, Semino-Mora C, Doi SQ, Dubois A. Specific and sensitive detection of H. pylori in biological specimens by real-time RT-PCR and in situ hybridization. PLoS One. 2008 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002689. http://www.plosone.org/doi/pone.0002689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Semino-Mora C, Doi SQ, Marty A, Simko V, Carlstedt I, et al. Intracellular and interstitial expression of Helicobacter pylori virulence genes in gastric precancerous intestinal metaplasia and adenocarcinoma. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1165–1177. doi: 10.1086/368133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–1181. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cover TL, Glupczynski Y, Lage AP, Burette A, Tummuru MK, et al. Serologic detection of infection with cagA+ Helicobacter pylori strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1496–1500. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1496-1500.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oderda G, Figura N, Bayeli P, Basagni C, Bugnoli M, et al. Serologic IgG recognition of Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin-associated protein, peptic ulcer and gastroduodenal pathology in childhood. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1993;5:695–699. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Regula J, Hennig E, Burzykowski T, Orlowska J, Przytulski K, et al. Multivariate analysis of risk factors for development of duodenal ulcer in Helicobacter pylori-infected patients. Digestion. 2003;67:25–31. doi: 10.1159/000070394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaoka Y, Souchek J, Odenbreit S, Haas R, Arnqvist A, et al. Discrimination between cases of duodenal ulcer and gastritis on the basis of putative virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2244–2246. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.6.2244-2246.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masters C, Letley D, Atherton JC. The Effect of Natural Polymorphisms Upstream of the Helicobacter pylori Vacuolating Cytotoxin Gene, vacA, on vacA Transcription Levels. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(Suppl 1):A-85, 608. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott DR, Marcus EA, Wen Y, Oh J, Sachs G. Gene expression in vivo shows that Helicobacter pylori colonizes an acidic niche on the gastric surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7235–7240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702300104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minohara Y, Boyd DK, Hawkins HK, Ernst PB, Patel J, et al. The effect of the cag pathogenicity island on binding of Helicobacter pylori to gastric epithelial cells and the subsequent induction of apoptosis. Helicobacter. 2007;12:583–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Figura N, Vindigni C, Covacci A, Presenti L, Burroni D, et al. cagA positive and negative Helicobacter pylori strains are simultaneously present in the stomach of most patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia: relevance to histological damage. Gut. 1998;42:772–778. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.6.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]