Abstract

Objective

Patients with chronic illnesses are particularly vulnerable to drug coverage gaps. We examined drug costs and entry and exit rates into the Part D coverage gap for beneficiaries with diabetes in two large California Medicare Advantage managed care plans.

Study Design

Cross-sectional observational study.

Methods

Medicare Advantage Part D beneficiaries with diabetes from two large California health plans who were continuously enrolled in 2006 and had a drug coverage gap starting at $2,250. Entry and exit into the gap, total drug costs, and out-of-pocket drug costs were determined using pharmacy databases.

Results

In 2006, 26% of the 42,801 beneficiaries with diabetes reached the coverage gap. 2% of beneficiaries exited the gap and qualified for `catastrophic' coverage. Beneficiaries incurred a mean of $2,182 in total drug costs during 2006. Drug expenditures remained stable over the year for beneficiaries who did not enter the gap. For beneficiaries who entered the gap, total drug costs were higher overall and decreased at year's end as out-of-pocket expenses increased.

Conclusions

Fewer diabetes patients in this study entered the coverage gap than had been previously estimated, but entry rate was much higher than that of the general Medicare Advantage Part D population. Patients entering the gap had lower subsequent monthly drug expenditures; this may be due to lower than expected drug prices and higher use of generics in managed care, or potentially signal lower drug adherence. Future work should examine these hypotheses and explore risk factors for entering the Part D coverage gap.

Keywords: Medicare Part D, diabetes, coverage gap

INTRODUCTION

The Medicare Part D drug benefit, introduced in January 2006 was designed to help address the needs of seniors with high out-of-pocket costs for medications (1,2,3) and to provide continuous access to needed chronic illness medications (3,4). A unique feature of Medicare Part D is that under the standard benefit structure, enrollees have a potential coverage “gap”, commonly referred to as a “doughnut hole”, in prescription drug cost coverage. The standard Part D benefit in 2006 began with partial coverage for the first $2,250 of total drug costs in 2006, followed by a period of no coverage until patients reach cumulative out-of-pocket costs of $3,600 in 2006 (5). At the end of the gap “catastrophic coverage” begins; patients often pay only 5% of drug costs or a pre-determined co-pay from that time forward (6). An estimated 18.2 million beneficiaries (89% of Part D enrollees not receiving a low income subsidy) in 2006 were enrolled in a Medicare Part D plan with a full coverage gap (7).

Patients with chronic illnesses such as diabetes are at particularly high risk for facing high drug and other out-of-pocket costs given their need for chronic drug therapy, and frequent need for multiple drugs to treat comorbid conditions. Persons with diabetes in particular often require daily medication to control their blood sugar levels, plus often require concurrent chronic treatment for other conditions (8,9,10). The cost of managing chronic illness is high for the government as well, and the diabetes population is of particular interest. While approximately 20% of Medicare beneficiaries have diabetes, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has estimated that up to 32% of all Medicare spending could be attributed to patients with diabetes (11). The costs for drug such as insulin and oral agents to control diabetes account for up to 12% of the health care expenditures attributable to the disease (12).

The high levels of clinical need for drug therapy combined with substantial out-of-pocket costs for patients with diabetes may make them more vulnerable to cost-related medication non-adherence (3,13). Studies suggest that elderly patients reduce their medication use when faced with limited prescription benefit coverage (1,6), and experience adverse health consequences including non-elective hospitalizations and death (14,15). Current studies examining the effect of Medicare Part D on adherence and cost are mixed. Some studies suggest Medicare Part D's introduction improved adherence and decreased out-of-pocket costs (16,17), while others found evidence that drug costs decreased medication adherence, especially for those entering the coverage gap (1,18). Such effects may be more pronounced in patients with comorbidities and worse health status (19) such as those with diabetes.

One recent study conducted in a Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug (MAPD) plan offered by an integrated delivery system included in this study reported that 8% of beneficiaries overall entered the coverage gap in 2006 (18), a rate much lower than pre-2006 projections of gap entry rates for the general population (6). One pre-Part D implementation study of diabetic Medicare beneficiaries estimated that 64% would enter the coverage gap in the first year (20). However, there is currently no empirical information on how many seniors with diabetes enter and exit the “doughnut hole” of prescription drug coverage in Medicare Part D plans.

This study examines total drug costs, out-of-pocket drug costs, and the rates of entry and exit into the Medicare Part D coverage gap in an important subset of Medicare beneficiaries, those with diabetes, for patients from two large MAPD plans in California.

METHODS

Patients were included in the study if they were identified as having diabetes and were beneficiaries of the Medicare Part D program ages 65 and above from two large health plans offering MAPD benefits in California in 2006. The first plan (Plan A) is a for-profit network model HMO serving patients primarily in Southern California. The second plan (Plan B) is a not-for-profit integrated delivery system HMO model that serves patients in Northern California.

Patients were determined to have diabetes if they had filled at least one glucose-lowering medication (e.g., insulin, metformin) at some point during 2005. Fifteen-percent of Medicare beneficiaries in both plans had diabetes based on this criterion. In order to be eligible for the study, these diabetes patients were also required to have been continuously enrolled in the health plan between 1/01/06 and 12/31/06 so that complete pharmacy data could be captured (11% excluded). An additional 26% were excluded from the study if they had any type of drug cost coverage during the gap, including a supplemental retiree benefit plan or a low-income supplement provided by Medicaid or through the Part D program.

Patient age, gender, and Medicare Part D enrollment were determined from automated databases on demographics and coverage status maintained by both plans. Co-morbidity data was determined using 2005 claims data for patients in Plan A, and 2005 automated outpatient clinical records for patients in Plan B.

Individual entry and exit into the Medicare Part D coverage gap was determined using pharmacy claims data from Plan A, and automated outpatient pharmacy records for patients in Plan B. In both plans, patients reached the coverage gap after $2,250 in total drug costs, which includes drug acquisition costs and dispensing fees. Patients exited the gap once a total of $3,600 in out-of-pocket costs was achieved during the year.

This study was developed and approved by the Steering Committee of the Translating Research in Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Study and conducted by researchers in two TRIAD Translational Research Centers. The study protocol was approved by the Kaiser Permanente Northern California and University of California at Los Angeles Institutional Review Boards.

RESULTS

The MAPD plans had a total of 42,801 beneficiaries with diabetes that met study criteria. Almost half (47%) were between 65 and 74 years of age; 43% were between 75 and 84 years of age, and 10% were age 85 and older. Fifty-one percent of study subjects were female. Most patients were using only oral hypoglycemics to manage their diabetes (81%). Eighty percent had an ICD-9 diagnosis of hypertension, and 65% had hyperlipidemia. The percent of elderly patients, percent of female patients, diabetes drug use patterns, and comorbidity burden were similar in both plans. During 2006, 26% of diabetes patients entered the coverage gap. Only 2% of all beneficiaries in the study had $3,600 of total drug costs, and therefore qualified for `catastrophic coverage' drug cost assistance in 2006.

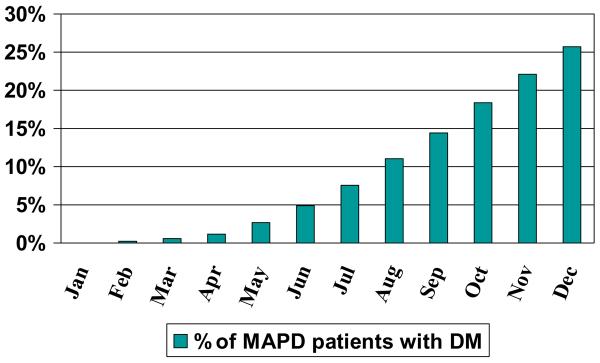

Figure 1 shows the cumulative percentage of diabetes patients entering the coverage gap by month. Less than 1% of patients entered the prescription drug coverage gap in the first quarter of 2006 (January-March); by the end of the second quarter (June) only 5% had entered the coverage gap. More than half of the patients who entered the coverage gap during the year did so after August 31st.

Figure 1.

Cumulative Percent of Patients Reaching Medicare Part D Coverage Gap in 2006, by Month

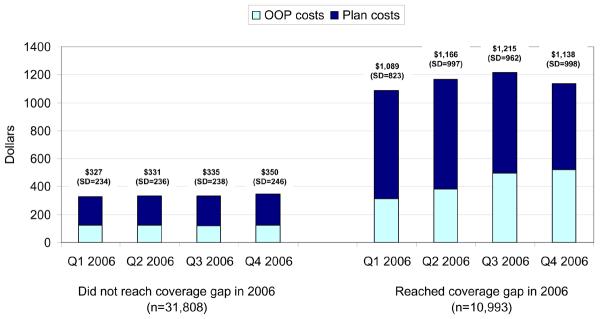

On average, diabetes patients incurred $2,182 in total drug costs during 2006, with a mean of $807 in out-of-pocket drug costs to patients. Figure 2 shows the amount of total and out-of-pocket drug expenditures for the MAPD beneficiaries in the study who reached and did not reach the coverage gap in 2006. For those who did not reach the gap, both total drug expenditures and out-of-pocket drug expenditures remained stable over time during the year. For the 26% of MAPD patients in the study who reached the coverage gap in 2006, total drug costs were much higher overall, and decreased toward the end of the year as out-of-pocket drug expenses increased. ANOVA tests of the differences in drug costs showed that the decrease in total drug costs between Q3 and Q4 of 2006 and the quarterly increases in out-of-pocket costs for these patients were significant (p<.01).

Figure 2.

Average Per-Patient Quarterly Total Drug Costs in 2006

DISCUSSION

Data from both Medicare Advantage plans in this study suggests that Medicare Advantage beneficiaries with diabetes are entering and exiting the `doughnut hole' of drug coverage at a far lower rate than originally expected. One study projected that 64% of patients with diabetes who were eligible for Medicare Part D would have drug costs exceeding $2,250 and incur significant out-of-pocket spending in 2006 (20). This study finds a much lower rate of gap entry than this original prediction (26% of patients entered the gap in 2006).

There are many potential explanations for the disparity between previous projections and the actual experience of diabetes patients in these Medicare Advantage plans. One possible reason is that patients in these managed care plans are receiving more generic therapies than those in the general diabetes population previously studied. These managed care plans may provide appropriate drug therapies in ways that lower costs through methods such as through formulary management, generic substitution, or multitiered copayments (20, 21).

Another potential explanation for the difference between projected and actual rates of entering and exiting the coverage gap is that patients could use fewer medications up front to avoid entering the coverage gap, and then continue to use fewer medications once the `doughnut hole' is reached. Previous projections of gap entry rates were based on assumptions that patient drug spending would stay steady as patients approach the gap, and after the gap was reached (20). Our findings demonstrate that total drug costs were decreasing in the latter part of the year as out-of-pocket costs were rising, which suggests that medication use by diabetes patients could be decreasing once they hit the coverage gap. This would support the findings of other Medicare Part D studies which found evidence of decreased drug adherence based on cost (1,18), especially for patients with worse health status such as those with diabetes (19). Since cost-related medication non-adherence is with lower health status, greater rates of cardiac adverse events, and increased use of emergency services (3), particular attention should be paid to addressing this potential risk for diabetes patients in Medicare Part D.

This study has a number of limitations that should be noted. This study only examines patients in Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug plans, which make up 28% of the total Part D population; most Medicare Part D enrollees are covered by stand-alone Prescription Drug Plans (PDP) (23). Further research will be required to examine gap entry rates, drug costs, and risk for cost-related medication non-adherence in PDP patients with diabetes. This study identifies diabetes patients through drug claims data, and not diagnosis codes; however, a sensitivity analysis showed that also requiring a diabetes diagnosis in addition to antidiabitic drug use resulted in a very small number of patient exclusions (<5%.) This study only examines the experience of Medicare Part D enrollees in two California plans, who may differ from enrollees nationally. However, examination of Plan A diabetes enrollee data in 7 other states (Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, and Washington) show that the Plan B gap entry rate for all Western states combined is almost identical to that of California alone. This result suggests that the results presented here are representative of the overall MAPD enrollees' experience.

Finally, this study has not specifically demonstrated that decreases in drug spending leads to adverse outcomes such as increased mortality and morbidity. Future research is required to examine this important issue.

CONCLUSION

This study is the first to examine actual total and out-of-pocket drug costs, and empirical rates of entering and exiting the coverage gap, in a Medicare Advantage population with chronic illness. Our findings suggest that diabetes patients are more vulnerable to entering the coverage gap than MAPD beneficiaries in the general population, but are entering the gap at lower-than-expected rates for diabetes patients. These lower than expected costs and rates of experiencing the `doughnut hole' may reflect efforts by Medicare Advantage plans to provide appropriate drug therapies in ways that lower costs, or may suggest that seniors are significantly lowering their use of prescription medications in response to high out-of-pocket costs. This is a critically important question for policy makers, patients, and their providers, and further research should examine specific patient responses to gaps in prescription drug coverage in Medicare.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by Centers for Disease Control, Contract no. U58/CCU923527-04-1; the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Institute of Aging (R01HS013902-01) and NIA (R01-AG029316-01). Dr. Schmittdiel is supported by the Office of Research in Women's Health Building Interdisciplinary Careers in Women's Health K12 Career Development Award (K12HD052163). Dr. Mangione is partially supported by the UCLA Resource Center for Minority Aging Research (NIA #2P30AG021684-06)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is the pre-publication version of a manuscript that has been accepted for publication in The American Journal of Managed Care (AJMC). This version does not include post-acceptance editing and formatting. The editors and publisher of AJMC are not responsible for the content or presentation of the prepublication version of the manuscript or any version that a third party derives from it. Readers who wish to access the definitive published version of this manuscript and any ancillary material related to it (eg, correspondence, corrections, editorials, etc) should go to www.ajmc.com or to the print issue in which the article appears. Those who cite this manuscript should cite the published version, as it is the official version of record.

References

- 1.Neuman P, Strollo MK, Guterman S, et al. Medicare prescription drug benefit progress report: findings from a 2006 national survey of seniors. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007 Sep-Oct;26(5):w630–643. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.w630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Safran DG, Neuman P, Schoen C, et al. Prescription drug coverage and seniors: findings from a 2003 national survey. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005 Jan-Jun;:W5–152. W155–166. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.152. Suppl Web Exclusives. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soumerai SB, Pierre-Jacques M, Zhang F, et al. Cost-related medication nonadherence among elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries: a national survey 1 year before the Medicare drug benefit. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Sep 25;166(17):1829–1835. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bach PB, McClellan MB. A prescription for a modern Medicare program. N Engl J Med. 2005 Dec 29;353(26):2733–2735. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bach PB, McClellan MB. The first months of the prescription-drug benefit— CMS update. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jun 1;354(22):2312–2314. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuart S, Briesacher BA, Shea DG, Cooper B, Baysac FS, Limcangco MR. Riding the roller coaster: the ups and downs in out-of-pocket spending under the standard Medicare drug benefit. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005 Jul-Aug;24(4):1022–1031. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.4.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MedPac Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Ch. 4: Update on Medicare Private Plans. 2007 March; 2007. http://www.medpac.gov/documents/Mar07_EntireReport.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2008.

- 8.American Diabetes Association Implications of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Care. 2003 Jan;26(Suppl 1):S25–27. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(Suppl 1):S32–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearson TA, Blair SN, Daniels SR, et al. AHA Guidelines for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: 2002 Update: Consensus Panel Guide to Comprehensive Risk Reduction for Adult Patients Without Coronary or Other Atherosclerotic Vascular Diseases. American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee. Circulation. 2002 Jul 16;106(3):388–391. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020190.45892.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashkenazy R, Abrahamson MJ. Medicare coverage for patients with diabetes. A national plan with individual consequences. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 Apr;21(4):386–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Diabetes Association Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2007. Diabetes Car. 31(3):596–615. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson JE, Doescher MP, Saver BG, Fishman P. Prescription drug coverage, health, and medication acquisition among seniors with one or more chronic conditions. Med Care. 2004 Nov;42(11):1056–1065. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200411000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA, et al. Effect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Sep 25;166(17):1836–1841. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu J, Price M, Huang J, et al. Unintended consequences of caps on Medicare drug benefits. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jun 1;354(22):2349–2359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa054436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lichtenberg FR, Sun SX. The impact of Medicare Part D on prescription drug use by the elderly. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(6):1735–1744. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin W, Basu A, Zhang JX, Rabbani A, Meltzer DO, Alexander GC. The effect of the Medicare Part D prescription benefit on drug utilization and expenditures. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(3):169–177. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-3-200802050-00200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu J, Fung V, Price M, Huang J, Brand R, Hui R, Fireman B, Newhouse JP. Medicare beneficiaries' knowledge of the Part D prescription drug benefit and response to drug costs. JAMA. 2008 April 23;299(16):1954–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.16.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madden JM, Graves AJ, Zhang F, et al. Cost-related medication nonadherence and spending on basic needs following implementation of Medicare Part D. JAMA. 2008;299(16):1922–1928. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.16.1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tjia J, Schwartz JS. Will the Medicare prescription drug benefit eliminate cost barriers for older adults with diabetes mellitus? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006 Apr;54(4):606–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saleh SS, Weller W, Hannan E. The effect of insurance type on prescription drug use and expenditures among elderly Medicare beneficiaries. J Health Human Serv Admin. 2007;30(1):50–74. Summer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilman BH, Kautter J. Impact of multitiered copayments on the use and cost of prescription drugs among Medicare beneficiaries. HSR. 2008;43(2):478–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00774.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cubanski J, Neuman P. Status report on Medicare Part D enrollment in 2006: analysis of plan-specific market share and coverage. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007 Jan-Feb;26(1):w1–w12. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]