In a letter to his unhelpful uncle, Lord Burghley, in 1592 Francis Bacon outlined a plan. He wanted to bring about a reorganization of learning, which had languished during the Middle Ages and beyond, despite Roger Bacon's recognition, in his Opus Maius of 1267, of the importance of experimental science, mathematics, and language. The latter-day Bacon constructed his plan as a programme that he called Instauratio Magna, a Great Instauration, which was also the title he gave to a preliminary description of it, published in 1620 and dedicated to King James (Figure 1). Bacon's ‘grand edifice’ had seven strands:

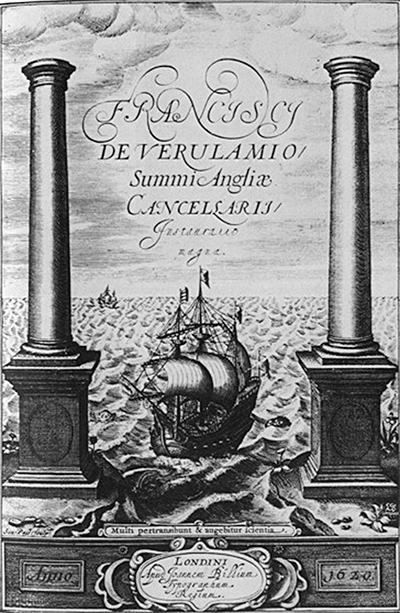

Figure 1.

The title page of Francis Bacon's Instauratio Magna (1620)

Introductory principles

Classification of sciences

Scientific methods

Experimentation

Historical survey of scientific developments

Foresight of scientific developments

Practical applications to ensure the betterment of mankind.

The time was ripe for change. The words ‘pathology’ and ‘physiology’ had just entered the English language, and ‘therapeutics’ and ‘pharmacology’ were soon to do so [1]. Bacon began his never-to-be-completed campaign with a book called The Advancement of Learning (1605), a preliminary version of a longer Latin text De Augmentis Scientiarum (1623), in which he described the decline of scientific method, reviewing the weaknesses of academics and universities, a current lack of scientific collaboration, and the neglect of science by governments. This book was an introduction to Bacon's major work, the Novum Organum (1620), in which he reaffirmed the importance of experimentation and outlined the inductive method of reasoning. Bacon's last book, The New Atlantis (1627), was a utopian fable, in which he imagined a paternalistic government, supporting science through the establishment of a Royal College of Research, and predicted numerous inventions and techniques, such as aircraft and submarines, telephony and refrigeration. It was while undertaking experiments in the last of these that he died from an affection acquired while stuffing a fowl with snow.

Through this fragmentary body of work, Bacon earned the title ‘high priest of modern science’. His plan was a grandiose one, intended to culminate in a kind of earthly paradise through the instauration, or restoration, of scientific learning and method. Although some of the above account has strong contemporary resonances, it would be excessive to claim that one of the main current aims of the British Pharmacological Society (BPS) – to restore Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics (CPT) as a scientific and practical discipline in the UK – is as exalted as Bacon's intentions were. It is nevertheless true that we are currently experiencing an exciting period of instauration or, as others have called it [2], a renaissance.

Manpower problems

There is a long prehistory to clinical pharmacology, from the

(Materia Medica) of Dioscorides through to the invention of the terms ‘human pharmacology’ and ‘clinical pharmacology’ in the first half of the 20th century. However, it can reasonably be said that the subject came of age in 1960, when Dilling's Clinical Pharmacology and Laurence's textbook of the same name were both published. After a period of quiet growth in the 1960s, two reports, one from the Royal College of Physicians of London (1969) and one from the World Health Organization (1970), highlighted the need for more practitioners [3]. As a result, between 1970 and 1990 the number of consultant clinical pharmacologists in the UK increased to about 70. However, following the first research assessment exercise to cover the entire higher education sector (1992), and in my view related at least in part to that event, the number started to fall. I shall not detail here all the reasons for this decline, but we know, based on a thorough search of the manpower figures [4], that by the year 2003 the number had fallen to just over 50, or less than one per million of the UK population. My own count of the current manpower, based on those whom I know personally or have knowledge of through other sources, is similar. For comparison, Croatia, which some of us visited 2 years ago by courtesy of the British Council, has about 30 clinical pharmacologists for a population of only 4.5 million, one per 150 000.

(Materia Medica) of Dioscorides through to the invention of the terms ‘human pharmacology’ and ‘clinical pharmacology’ in the first half of the 20th century. However, it can reasonably be said that the subject came of age in 1960, when Dilling's Clinical Pharmacology and Laurence's textbook of the same name were both published. After a period of quiet growth in the 1960s, two reports, one from the Royal College of Physicians of London (1969) and one from the World Health Organization (1970), highlighted the need for more practitioners [3]. As a result, between 1970 and 1990 the number of consultant clinical pharmacologists in the UK increased to about 70. However, following the first research assessment exercise to cover the entire higher education sector (1992), and in my view related at least in part to that event, the number started to fall. I shall not detail here all the reasons for this decline, but we know, based on a thorough search of the manpower figures [4], that by the year 2003 the number had fallen to just over 50, or less than one per million of the UK population. My own count of the current manpower, based on those whom I know personally or have knowledge of through other sources, is similar. For comparison, Croatia, which some of us visited 2 years ago by courtesy of the British Council, has about 30 clinical pharmacologists for a population of only 4.5 million, one per 150 000.

Promoting clinical pharmacology

In July 2006, the BPS persuaded Fiona Fox at the Science Media Centre in the Royal Institution to hold a press briefing that she called a ‘drugs bust’. We told the assembled science correspondents that the lack of teaching of medical students in the science and practices of therapeutics was endangering patient care; some of the resulting headlines were lurid. The Editor of the Student BMJ asked us to write an editorial on the subject, and the text that we submitted, based on an earlier editorial [5], was picked up by the BMJ and published there instead [6]. Later, in my FitzPatrick Lecture to the Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians in London in 2007, I reiterated our concerns [7].

The correspondence columns in response to the BMJ editorial resounded with support, but the then Chairman of the Teaching Committee of the General Medical Council (GMC), Peter Rubin, himself a Professor of Therapeutics in Nottingham, and today Chairman of the GMC, wrote to chide us for making rash statements in the absence of evidence [8]. We protested that we had evidence and had referred to it in our editorial, but suggested that it would be more productive to conduct the debate outside the correspondence columns of the journal [9]. We proposed a meeting of various interested parties, and the GMC arranged such a meeting in January 2007. We were convinced of the justice of our case, but even so were surprised at the amount of support that we received at that meeting from medical students, junior doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and others.

At this point the GMC and the Medical Schools Council set up a working party, at which the problems of teaching practical therapeutics to medical students were discussed. This led to a report [10], in which it was recommended, among other things, that there should be a statement of the required competencies of all Foundation doctors in relation to prescribing in the draft version of Tomorrow's Doctors, the GMC's blueprint for training medical students [11]. That draft version went out for consultation. Later, the House of Commons Health Committee, in their report ‘Patient Safety’ (3 July 2009), noted that ‘there are serious deficiencies in the undergraduate medical curriculum, Tomorrow's Doctors, which are detrimental to patient safety, in respect of training in clinical pharmacology and therapeutics’ and recommended that ‘[this] must be addressed in the next edition of Tomorrow's Doctors’[12]. At about the same time, support also came from NHS managers, through a questionnaire study carried out by the organization ‘Skills for Health’, in which they highlighted their concerns about prescribing and the need for more undergraduate teaching in both the basic sciences of pharmacology and clinical pharmacology and the practicalities of prescribing [13]. The final version of Tomorrow's Doctors contained the original text about prescribing, exactly as it had been drafted by the working party [14].

There is clear evidence of dissatisfaction among current medical students about their preparedness to prescribe and of the need for more teaching of practical therapeutics based on scientific principles; it is the quantity of teaching about which the students are concerned, not the quality, which they report to be high [15]. Evidence of students' worries originally came from studies carried out by members of the BPS in 2006–2007 [16–18], and was therefore open to the criticism of vested interests. However, in a study of 193 pre-registration house officers and 212 consultant educational supervisors in the West Midlands, both groups ranked the house officers' communication skills areas highest (best prepared) and ranked basic doctoring skills (such as prescribing, treatment, decision making, and emergencies) lowest [19]. A subsequent independent study, funded by the GMC, confirmed that medical students feel prepared for all the duties that they will be expected to carry out as newly qualified doctors – except prescribing [20]. Furthermore, in an independent study in Nottingham, first-year (Foundation Year) doctors ‘were deemed not well prepared for prescribing’ in the eyes of 107 consultants and 121 specialist registrars [21].

In a subject such as medicine, in which learning continues life long, anyone who is behind to start with will always be catching up, particularly in such a rapidly changing and increasingly complex subject as drug therapy. It is therefore vital that a well-founded education be provided as early as possible. The new version of Tomorrow's Doctors recognizes this and will come into force at the start of the academic year 2011–2012. It will be up to medical schools to see to it that the appropriate teaching is available to ensure that its requirements are fulfilled. We shall continue to suggest that that will best be done by appointing clinical pharmacologists [22]. As part of its efforts to improve undergraduate education, the BPS has gone into partnership with the Department of Health and the Medical Schools Council to create a website for education in prescribing [23]. This will be launched in 2010 and made freely available to all UK medical schools.

Independent developments

The charge of special pleading in our own cause has long bothered us – if experts cannot point to a problem that needs rectifying without being accused of trying to feather their own nests in the process, change cannot come about in important areas that need expert attention. However, when those outside the field become concerned as well, there is an opportunity for change. And that is what happened during 2009.

In 2008 the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) established an independent working party, under the chairmanship of the Editor of The Lancet, Richard Horton, ‘to review the current and future conditions for, and barriers to, a dynamic, productive and sustainable relationship between the NHS, academic medicine and the pharmaceutical industry’[24]. The working party was independent of Clinical Pharmacology, although the BPS submitted evidence. The final recommendation in the report (published in February 2009) was that ‘The RCP should create a Pharmaceutical Forum … Ways to trigger a renaissance of clinical pharmacology should be a priority issue for this Forum’[2]. A forum (now called the Medicines Forum) has since been established and has reaffirmed that priority; a working party of the Forum is looking into ways of furthering this aim.

Other positive developments have occurred at an even higher level. Following a meeting between the UK Government and representatives of pharmaceutical companies, a new Government Office for Life Sciences (OLS) was established in 2009 under the leadership of Lord Drayson, Minister for Science and Innovation in the newly formed Department for Business, Innovation and Skills [25]. The scope of the OLS was widened from pharmaceutical companies to include biotech companies and those producing medical devices and diagnostics, with the aim of implementing a strategic plan of action to ensure that the UK fully realizes its position of leadership in this area during the current economic downturn. The BPS was invited by the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry to discuss how the development of clinical pharmacology could be enhanced under this initiative. The Life Sciences Blueprint that was subsequently published in July 2009 [26] stated that ‘The Government will, in partnership with the H[igher] E[ducation] sector and industry, establish an industry and HE forum … [whose] first two tasks … will be to assess the curriculum for clinical pharmacology in medical and pharmacy degrees and higher medical training, and evaluate the impact of the significant public and industry funding in addressing the in vivo sciences (pharmacology, pathology, toxicology and physiology) skills gaps’. The Blueprint also recognized that ‘The provision of high quality-care requires clinicians to be familiar with the relevant practices in clinical pharmacology and pathology. This is important to enable them to evaluate and prescribe innovative medicines’. A working party of the forum mentioned in the Blueprint has been established and will make recommendations to the OLS early in 2010.

Following the publication of the Life Sciences Blueprint, highlighting the critical skills gap, the MRC announced £3.7M funding for two new Clinical Pharmacology and Pathology Fellowship Programmes [27]. It is likely that these programmes will fund the training of 10–12 new clinical pharmacologists over the next 6 years.

Another research initiative arose from a meeting that members of the BPS had in September 2007 at the Wellcome Trust, following which the Trust established four major programmes in translational medicine and therapeutics [28], all led by clinical pharmacologists, all with industrial collaborators. The translational aspects of clinical pharmacology, as a scientific, clinical, and teaching specialty, should not be ignored [29].

The time lines of all these positive developments are shown in Figures 2 and 3. Figure 2 shows the events during 2006–2008 and Figure 3 the events during 2009. I had originally intended to include this information in a single figure, but the pace of activity during 2009 made it necessary to construct a separate figure. Extra insight into the nature of these events comes from the colour key in these figures (or, for those with a monochrome copy, the box-surround and typography):

Figure 2.

Developments in clinical pharmacology during 2006–2008; the colour code is explained in the text

Figure 3.

Developments in clinical pharmacology during 2009; the colour code is explained in the text

| Colour | Box | Typography | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black | Solid | Roman lower case | Papers/lectures by members of the BPS |

| Blue | Solid | Upper case | Press briefings at the Science Media Centre |

| Green | Dotted | Roman lower case | Meetings with other bodies |

| Orange | Solid | Italics | Reports or studies by other bodies |

| Red | Dotted | Upper case | Funding streams. |

The period 2006–2008 (Figure 2) is dominated by black, with orange and green less prominent. However, during 2009 (Figure 3) the orange and green events have become more frequent, showing the concerns that those outside the BPS have started to have.

Other BPS activities

Throughout the last 4 years, the BPS has been highly active in bringing to public attention its concerns about deficiencies in undergraduate training and the relative lack of expertise in pharmacology and clinical pharmacology. In 2007 we appointed a Prescribing Initiative Fellow, who, among other things, produced two major systematic reviews on the teaching of practical prescribing [30] and medication errors made by junior doctors [31]; both were published in the special June 2009 issue of the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology on medication errors [32].

We are also currently revising the undergraduate curriculum. Our postgraduate training programme is also currently under review through discussions with the Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board (PMETB), whose merger with the GMC is planned for 2010, and a new training programme has been developed. Dual accreditation in CPT and General (Internal) Medicine will continue to be available, but dual accreditation in CPT with other specialties will be more difficult to achieve, because of PMETB's new rules, although still possible. Clinical toxicology should also continue to be an important part of the training and practice of clinical pharmacologists. We should, nevertheless, like to encourage trainees to undertake dual accreditation in CPT and other specialties, such as cardiology, geriatrics, gastroenterology, and rheumatology, and to encourage clinical pharmacology training in general practice, where the majority of prescribing occurs [33, 34]. In this way we hope to be able to generate, in addition to a core of specialist clinical pharmacologists, a penumbra of specialists in other disciplines, all trained in CPT and able to contribute to teaching and training in relation to their own specialty. We should also, as we have done in the past, continue to train clinical pharmacologists whose careers take them into pharmaceutical companies or regulatory agencies.

The Society also collaborated in 2007–2008 with Professor Tilli Tansey and her colleagues in the Wellcome Trust in holding two Wellcome Witness Seminars, at which the future of clinical pharmacology was discussed by a large number of clinical pharmacologists and others, in the light of the history of the subject, as viewed by its exponents [35].

Other activities that we have undertaken include the further development of the BPS Prescribing Group for allied health professionals, Specialist Registrar training days at the annual Winter meeting, support for regional clinical pharmacology group meetings (e.g. the Clinical Pharmacology Colloquium), the development of an efficient response mechanism to national consultations, interactions with the Science Media Centre, and podcasts related to Society lectures (which are featured on the BPS's website).

We have also held successful meetings, including a joint RCP/BPS meeting on ‘Rational Prescribing’, held in the RCP on 7 May 2008; BPS sponsored sessions at the Cheltenham Science Festival: ‘NHS Funding – NICE or Nasty?’ (4 June 2008) and ‘The Science of Curry’ (3 June 2009); a BPS sponsored symposium ‘Clinical Pharmacology: Working With Patients’ and a hypertension symposium at the meeting of the European Association for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics in Edinburgh in July 2009; and a joint BPS/Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain symposium on diabetes mellitus during the British Pharmaceutical Conference on 9 September 2009. The last was part of our continuing programme in developing relationships with other learned societies, such as the British Toxicology Society and the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Medicine of the Royal College of Physicians, of which I am delighted to be an Honorary Fellow. We have plans for further joint meetings of this sort.

Finally, the first phase of the Society's Prescribing Initiative ended at the Winter meeting in London in December 2009, with an all-day interdisciplinary symposium, titled ‘Delivering safe prescribing in the NHS’. There were contributions from hospital consultants, junior doctors, general practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and others involved in education and other matters relevant to prescribing. In the next phase we shall concentrate on encouraging further interdisciplinary discussion and collaboration.

Future challenges

As this paper was going to press, more evidence emerged about the need for education in practical prescribing and the pharmacological science that underpins it. The EQUIP study [37] showed that the rate of prescribing errors among newly qualified doctors is about 9% and falls to about 7% among non-consultant career grade staff and 6% among hospital consultants. These data show that more experienced doctors make fewer errors, and although there are many possible reasons for this, the thesis that inadequate education is at least in part important is supported by the fact that the same pattern pertained in varying prescribing circumstances, both at the patient's time of admission and during the hospital stay. The authors of the report certainly considered education to be an important remedy – it featured in four of their five recommendations.

Thus, the most important of the several challenges that remain for the further instauration of clinical pharmacology will be to persuade Universities and NHS Trusts, including Primary Care Trusts, to establish new posts in clinical pharmacology, so that more education can be provided, both primary education at the undergraduate level and continuing education for qualified doctors. Although the number of consultant clinical pharmacologists in the UK has gone down since 1993, the appetite for training in clinical pharmacology has not diminished, according to my analysis of the 191 medical practitioners who are currently registered with the GMC as specialists in CPT – a number that far outstrips the number of identifiable UK clinical pharmacologists. As many medical practitioners have gained GMC registration in CPT in recent years as have done since the 1970s; many of them have gone on to work in other specialties, including cardiology, geriatrics, respiratory medicine, gastroenterology, rheumatology, and even public health. Furthermore, the BPS Diploma in Advanced Pharmacology [36] has attracted considerable interest from clinicians, particularly for workshops such as ‘Pharmacokinetics’ and ‘Early Phase Trials of New Drugs’.

There is no lack of interest in the subject among trainees, but there is a lack of jobs for them when they have qualified. We shall continue to put the case for creating new posts and shall seek to forge links with other clinical medical specialities and primary health care, to ensure that when earmarked clinical pharmacology posts do not exist, those with training in CPT can find jobs in other specialties, of which cardiology and geriatrics are currently the most popular among our trainees, so that clinical pharmacology expertise can be further spread through the medical community. Creating portfolio jobs may be a way of doing this. Discussions with other learned societies will be important: it has been rightly said that every physician should also be a clinical pharmacologist [38].

Envoi

The British Pharmacological Society aims, among other things, to be the leading society for the presentation, promotion and discussion of all matters relating to both pharmacology and CPT, and to provide advice on standards of teaching and practice to policy makers. The Society has striven to fulfil these aims during the last 4 years, with marked success, and I am confident that the pace of change will be maintained in the next few years.

An earlier version of this paper was first published in Pharmacology Matters, the newsletter of the British Pharmacological Society, in December 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson J. When I use a word … Materia medica, clinical pharmacology, and therapeutics. Q J Med. 2009 doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcp097. Jul 22 [Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royal College of Physicians of London. Innovating for Health: Patients, Physicians, the Pharmaceutical Industry, and the NHS. London: RCP; 2009. Available at http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/PROFESSIONAL-ISSUES/Pages/Physicians-and-the-Pharmaceutical-Industry.aspx (last accessed 9 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronson JK. On being 30. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maxwell SR, Webb DJ. Clinical pharmacology – too young to die? Lancet. 2006;367:799–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aronson JK. A prescription for better prescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:487–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aronson JK, Henderson G, Webb DJ, Rawlins MD. A prescription for better prescribing. BMJ. 2006;333:459–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38946.491829.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aronson JK. Clinical pharmacology: a suitable case for treatment. FitzPatrick Lecture, Royal College of Physicians, London, 2 April 2007: Available at https://admin.emea.acrobat.com/_a45839050/p74648562/ (last accessed 9 December 2009.

- 8.Rubin P. A prescription for better prescribing: medical education is a continuum. BMJ. 2006;333:601. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7568.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aronson JK, Barnett DB, Ferner RE, Ferro A, Henderson G, Maxwell SR, Rawlins MD, Webb DJ. Poor prescribing is continual. BMJ. 2006;333:756. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7571.756-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medical Schools Council. Outcomes of the Medical Schools Council Safe Prescribing Working Group. 11 February 2008. Available at http://www.medschools.ac.uk/News/Pages/Safe-Prescribing-Working-Group.aspx (last accessed 9 December 2009.

- 11.General Medical Council. Tomorrow's Doctors 2009: a draft for consultation. Available at https://gmc.e-consultation.net/econsult/uploads/TD%20Final.pdf (last accessed 9 December 2009.

- 12.House of Commons Health Committee. House of Commons Health Committee Report ‘Patient Safety’. 3 July 2009.

- 13.Skills for Health. Junior Doctors in the NHS: Preparing Medical Students for Employment and Post-graduate Training. 2009.

- 14.General Medical Council. Tomorrow's Doctors 2009. Available at http://www.gmc-uk.org/education/undergraduate/undergraduate_policy/tomorrows_doctors/tomorrows_doctors_2009.asp (last accessed 9 December 2009.

- 15.Ellis A. Prescribing rights: are medical students properly prepared for them? BMJ. 2002;324:1591. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han WH, Maxwell SR. Are medical students adequately trained to prescribe at the point of graduation? Views of first year foundation doctors. Scott Med J. 2006;51:27–32. doi: 10.1258/RSMSMJ.51.4.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tobaiqy M, McLay J, Ross S. Foundation year 1 doctors and clinical pharmacology and therapeutics teaching. A retrospective view in light of experience. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:363–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02925.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heaton A, Webb DJ, Maxwell SR. Undergraduate preparation for prescribing: the views of 2413 UK medical students and recent graduates. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66:128–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wall D, Bolshaw A, Carolan J. From undergraduate medical education to pre-registration house officer year: how prepared are students? Med Teach. 2006;28:435–9. doi: 10.1080/01421590600625171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Illing J, Morrow G, Kergon C, Burford B, Spencer J, Peile E, Davies C, Baldauf B, Allen M, Johnson N, Morrison J, Donaldson M, Whitelaw M, Field M. How prepared are medical graduates to begin practice? A comparison of three diverse UK medical schools. Final summary and conclusions for the GMC Education Committee, 2008. Available at http://www.gmc-uk.org/Preparedness_Poster.pdf_snapshot.pdf (last accessed 9 December 2009.

- 21.Matheson C, Matheson D. How well prepared are medical students for their first year as doctors? The views of consultants and specialist registrars in two teaching hospitals. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:582–9. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.071639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aronson J. In search of the right remedy. The Times. 2009. 8 September: 31.

- 23.Department of Health, British Pharmacological Society. Prescribe: e-learning for clinical pharmacology & prescribing. Available at http://www.cpt-prescribe.org.uk (last accessed 9 December 2009.

- 24.Horton R. The UK's NHS and pharma: from schism to symbiosis. Lancet. 2009;373:435–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. New Government office to reinforce success of life sciences industry. Available at http://www.dius.gov.uk/news_and_speeches/press_releases/office_life_sciences (last accessed 9 December 2009.

- 26.Office for Life Sciences. Life Sciences Blueprint. Available at http://www.dius.gov.uk/~/media/publications/O/ols-blueprint or via http://www.dius.gov.uk/ols (last accessed 9 December 2009.

- 27.Medical Research Council. MRC Clinical Pharmacology and Pathology Fellowship Programmes. 2009. Available at http://www.mrc.ac.uk/Fundingopportunities/Fellowships/Clinicalpharmacologypathology/index.htm (last accessed 9 December 2009.

- 28.Wellcome Trust brings academia and industry together to share clinical and research expertise. 2008. Available at http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/News/Media-office/Press-releases/2008/WTX049865.htm (last accessed 9 December 2009.

- 29.Aronson JK, Cohen A, Lewis LD. Clinical pharmacology – providing tools and expertise for translational medicine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:154–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross S, Loke YK. Do educational interventions improve prescribing by medical students and junior doctors? A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67:662–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross S, Bond C, Rothnie H, Thomas S, Macleod MJ. What is the scale of prescribing errors committed by junior doctors? A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67:629–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aronson JK, editor. Medication errors. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67:589–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walley T. Rational prescribing in primary care – a new role for clinical pharmacology? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;36:11–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb05884.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mant D. Clinical pharmacology and primary care. Pharmacol Matters. 2009;2:20–2. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reynolds LA, Tansey EM. Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine. Volume 33 – Clinical Pharmacology in the UK, c. 1950–2000: Influences and institutions. Volume 34 – Clinical Pharmacology in the UK, c. 1950–2000: Industry and regulation. Available at http://www.ucl.ac.uk/histmed/publications/wellcome_witnesses_c20th_med (last accessed 9 December 2009.

- 36.BPS. Diploma in Advanced Pharmacology. Available at http://www.bps.ac.uk/article447.asp (last accessed 9 December 2009.

- 37.Dornan T, Ashcroft D, Heathfield H, Lewis P, Miles J, Taylor D, Tully M, Wass V. An in depth investigation into causes of prescribing errors by foundation trainees in relation to their medical education. EQUIP study. http://www.rcoa.ac.uk/docs/GMC_prescribing-errors.pdf(lastaccessed9December,2009.

- 38.Wolff F. The myth of clinical pharmacology. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:390–1. doi: 10.1056/nejm196902132800725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]