Abstract

AIMS

Probenecid influences transport processes of drugs at several sites in the body and decreases elimination of several quinolones. We sought to explore extent, time course, and mechanism of the interaction between ciprofloxacin and probenecid at renal and nonrenal sites.

METHODS

A randomized, two-way crossover study was conducted in 12 healthy volunteers (in part previously published Clin Pharmacol Ther 1995; 58: 532–41). Subjects received 200 mg ciprofloxacin as 30-min intravenous infusion without and with 3 g probenecid divided into five oral doses. Drug concentrations were analysed by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry and high-performance liquid chromatography. Ciprofloxacin and its 2-aminoethylamino-metabolite (M1) in plasma and urine with and without probenecid were modelled simultaneously with WinNonlin®.

RESULTS

Data are ratio of geometric means (90% confidence intervals). Addition of probenecid reduced the median renal clearance from 23.8 to 8.25 l h−1[65% reduction (59, 71), P < 0.01] for ciprofloxacin and from 20.5 to 8.26 l h−1 (66% reduction (57, 73), P < 0.01] for M1 (estimated by modelling). Probenecid reduced ciprofloxacin nonrenal clearance by 8% (1, 14) (P < 0.08). Pharmacokinetic modelling indicated competitive inhibition of the renal tubular secretion of ciprofloxacin and M1 by probenecid. The affinity for the renal transporter was 4.4 times higher for ciprofloxacin and 3.6 times higher for M1 than for probenecid, based on the molar ratio. Probenecid did not affect volume of distribution of ciprofloxacin or M1, nonrenal clearance or intercompartmental clearance of ciprofloxacin.

CONCLUSIONS

Probenecid inhibited the renal tubular secretion of ciprofloxacin and M1, probably by a competitive mechanism and due to reaching >100-fold higher plasma concentrations. Formation of M1, nonrenal clearance and distribution of ciprofloxacin were not affected.

Keywords: ciprofloxacin, competitive inhibition, metabolite formation, modelling of pharmacokinetic interaction, probenecid

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Probenecid inhibits the active transport of both anionic and cationic drug molecules at various sites in the body.

Probenecid has been reported to decrease the elimination of several quinolones.

We are not aware of any reports where a mechanism-based model for the interaction of quinolones and probenecid in humans or animals has been developed.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Pharmacokinetic modelling indicates competitive inhibition of the renal tubular secretion of ciprofloxacin and its metabolite M1 by probenecid.

The affinity for the renal transporter was 4.4 times higher for ciprofloxacin and 3.6 times higher for M1 compared with probenecid, based on molar concentrations.

Probenecid did not affect volume of distribution of ciprofloxacin or M1, nonrenal clearance or intercompartmental clearance of ciprofloxacin.

Introduction

Ciprofloxacin is a quinolone antimicrobial with a broad range of activity against a variety of Gram-positive and -negative pathogens [1]. Renal clearance of ciprofloxacin exceeds the glomerular filtration rate, which indicates net tubular secretion. At physiological pH values, ciprofloxacin exists primarily as a zwitterion. Therefore it is likely to interact with organic anion as well as organic cation transporters in the renal tubular cells [2].

Probenecid has been reported to inhibit active transport of both anionic and cationic drug molecules at various sites in the body [3–5]. Furthermore, it is well known to decrease the renal secretion of numerous quinolones such as gatifloxacin [6], levofloxacin [7, 8], norfloxacin [9], fleroxacin [10] and enoxacin [11]. Moxifloxacin and sparfloxacin are not affected by probenecid [12, 13]. Our group has previously assessed the extent of interaction between probenecid, ciprofloxacin and its 2-aminoethylamino-metabolite (‘desethylene-ciprofloxacin’, M1) via noncompartmental analysis (NCA) [14]. As in most reports about quinolone-probenecid interactions, NCA was used then and the full time course of interaction between ciprofloxacin, M1 and probenecid was not modelled at this time and probenecid concentrations were not reported. Standard NCA in combination with anova statistics treat the presence or absence of probenecid as a categorical variable, but the concentration of probenecid is not included in the analysis.

Although standard NCA is an adequate method to explore the extent of interaction for the dose level used in the study, NCA does not directly account for the concentration dependence of an interaction. Therefore, NCA cannot predict the extent and time course of an interaction for other dosage regimens that might be relevant in clinical practice. Furthermore, it is difficult to predict the extent of interaction for patients with renal or hepatic failure by NCA. While such predictions also carry some uncertainty when using compartmental modelling, the latter technique is able to predict the time course of interaction for other dosage regimens and for patients with altered pharmacokinetics (PK).

Compartmental modelling explicitly studies the full time course of the metabolite formation as well as the time course of the effect of probenecid on the disposition of ciprofloxacin and M1. More specifically, compartmental modelling is more powerful at identifying the site(s) of interaction, to propose a mechanism of interaction for each site and to calculate relative affinities of the drugs to the transporter. Probably the most important advantage of a mechanism-based interaction model over NCA is the ability of an interaction model to predict the extent and time course of interaction for other dosage regimens via simulations. This ability of a mechanism-based interaction model can be used in pharmacodynamic (PD) simulations to predict the effect of an inhibitor on the probability of successful anti-infective treatment.

Our first objective was to develop a model that adequately describes the plasma concentrations and amounts in urine of ciprofloxacin and its metabolite M1, including the formation of M1. As our second objective we explored the possible influence of probenecid on renal clearance, nonrenal clearance and distribution of both ciprofloxacin and M1, as well as on the formation of M1. We sought to propose a possible mechanism for the interaction between ciprofloxacin, M1 and probenecid at each site of interaction. This mechanism-based interaction model can predict the time course of a PK interaction for other dosage regimens of interest. The data from this study on the PK of ciprofloxacin with and without probenecid were only published by a descriptive, noncompartmental analysis without modelling and without measuring probenecid concentrations previously [14]. The results on the PK of probenecid in combination with ciprofloxacin have not been published in a journal before. Part of the work described in the present report has previously been shown as a poster [15].

Methods

Study participants

Twelve healthy White subjects (six male and six female) participated in the study [14]. Prior to entry into the study, all subjects were given a physical examination, electrocardiography and laboratory tests including urinalysis and screening for drugs of abuse. During the drug administration periods, the volunteers were encouraged to report any discomfort or adverse reactions, and were closely observed by doctors. Each day of the study, subjects were asked to complete a questionnaire on their health status. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Bavarian Medical Association, Munich, Germany (Ethikkommission der Bayerischen Ärztekammer, München). All subjects gave their written informed consent prior to starting the study. The study was conducted according to the revised version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design and drug administration

This was a randomized, controlled, three-way crossover study. The third treatment, which is not reported here, was ciprofloxacin given together with charcoal. Subjects fasted from 12 h before until 6 h after administration of ciprofloxacin. In each of the two study periods reported here, each subject received a single dose of 200 mg ciprofloxacin (Ciprobay®) as 30-min intravenous (i.v.) infusion either alone or with 3 g of probenecid (Benemid®) divided into five oral doses. Probenecid was administered as follows: 500 mg at 10 h and 1000 mg at 2 h before the end of the ciprofloxacin infusion, and 500 mg at 4 h, 10 h and 16 h after the end of the ciprofloxacin infusion. Food and fluid intake were standardized on each study day. Treatment periods were separated by a wash-out period of at least 7 days. Subjects were requested to abstain from other medications during the study and from 1 week before start of the study, and subjects abstained from xanthine-containing foods and beverages, and alcohol on each study day.

Sampling schedule

Blood samples were collected in heparinized tubes from a forearm vein by use of an indwelling catheter contralateral to that used for drug administration. Blood samples were taken before the start of the ciprofloxacin infusion, 10 and 20 min after the start of infusion, at the end of infusion, and 5, 10, 20, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min and 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 24, 30, 36 and 48 h after the end of the infusion. The samples were centrifuged immediately. Urine samples were collected before ciprofloxacin administration and from start of the infusion to 2 h after the end of the infusion, as well as 2–4, 4–6, 6–8, 8–12, 12–16, 16–24, 24–36, 36–48, 48–72 and 72–96 h after the end of the ciprofloxacin infusion. Plasma and urine samples were immediately frozen and stored at –20 °C until analysis.

Determination of plasma and urine concentrations

Ciprofloxacin and M1 concentrations in plasma and urine were determined by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography as previously described [14]. In brief, the assay was linear between 0.020 and 10 mg l−1, with coefficients of correlation > 0.999. The between-day precision of the assay evaluated by pooled biologically derived plasma samples was found to be 2.6% (coefficient of variation) for ciprofloxacin and 3.5% for M1 (average values of three different concentrations).

Plasma samples were assayed for probenecid by use of a validated liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry method (IBMP, Nuremberg-Heroldsberg, Germany). The method was validated in the linear range from 2.500 to 100.0 µg ml−1. The lowest probenecid calibration standard of 2.500 µg ml−1 was set as the lower limit of quantification of the assay. There was no response at the retention time of probenecid at the sensitivity limit as well as for the internal standard. Overall precision of the method using quality control samples, as measured by relative standard deviation, was ≤ 5.5%. Overall accuracy, as measured by the percentage of theoretical recovery for probenecid, ranged from 90.5 to 102.6%.

Pharmacokinetic calculations

For NCA and compartmental modelling of the concentration–time data of ciprofloxacin and M1 in plasma and urine, and probenecid in plasma, WinNonlin® Professional (Version 4.0.1; Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, CA, USA) was utilized, as well as for anova statistics.

Noncompartmental analysis

The maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) were directly obtained from the plasma concentration–time curves for each subject. The area under the plasma concentration–time curve (AUC) was calculated for each subject utilizing the linear up/log down method as implemented in WinNonlin® Professional.

Compartmental modelling

Compartmental modelling was performed utilizing the Nelder–Mead simplex algorithm in WinNonlin®. Initially we developed the compartmental models for ciprofloxacin alone, ciprofloxacin plus M1, and probenecid separately. Then the individual models were combined to explore the interactions in the full models. We did not fix any of the model parameters, except duration of infusion. The plasma and urine profiles for ciprofloxacin with and without probenecid, plasma and urine profiles for M1 with and without probenecid, and plasma profiles for probenecid were modelled simultaneously.

Model discrimination

Model discrimination was based on: (i) visual inspection of the observed and predicted plasma and urine concentration–time curves; (ii) visual comparison of the patterns of residuals; (iii) intrasubject comparison of Akaike information criteria (AIC) between competing models; and (iv) the number of subjects who had the best AIC for each model. The AIC is a measure of goodness of fit and calculated as

The AIC considers both the goodness of model fit (weighted residual sum of squares, WRSS) and the number of parameters in the model (P). N is the number of observations. When comparing several models for the same dataset, the model associated with the smallest AIC value is regarded as the preferable model. As twice the value of P is added for calculation of the AIC, from two models that fit the data equally well (same WSSR), the model with the lower number of parameters is preferred. In this regard, the AIC balances the (slightly) improved curve fit for a more complex model against the additional complexity that is defined by the number of model parameters.

Disposition of ciprofloxacin and M1

Two- and three-compartment disposition models were evaluated for ciprofloxacin. The input of ciprofloxacin was modelled as a time delimited zero order process with 30 min duration. To describe the disposition of M1, one- and two-compartment models were evaluated.

For ciprofloxacin, identification of the renal and nonrenal components of clearance is possible because both plasma concentrations and amounts in urine were available. For M1 plasma and urine data were also available, which allows estimation of renal clearance for the metabolite. However, the total amount of metabolite formed is unknown. If no further assumptions are made, volume of distribution and nonrenal clearance of the metabolite are therefore not mathematically identifiable simultaneously.

In order to retain identifiability of all model parameters, for example, one of the following assumptions has to be made: (i) the metabolite is only eliminated renally; (ii) the volume of distribution for the metabolite is set to a prespecified value, e.g. to the estimated volume of distribution of ciprofloxacin; or (iii) the nonrenal clearance of the metabolite is set to a prespecified value, e.g. to the estimated nonrenal clearance of ciprofloxacin. More specifically, to ‘set’ a parameter to a prespecified value meant in our study that the same parameter was used for ciprofloxacin and M1 and that this one parameter is optimized during the estimation process. We observed in the NCA that the renal clearances of ciprofloxacin and M1 were very similar. Due to this and other observations during model development, we chose option (iii) and assumed that the nonrenal clearance of M1 was identical to the nonrenal clearance of ciprofloxacin for each treatment.

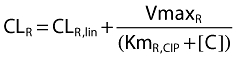

Renal clearance of ciprofloxacin was described as (see also Figure 2):

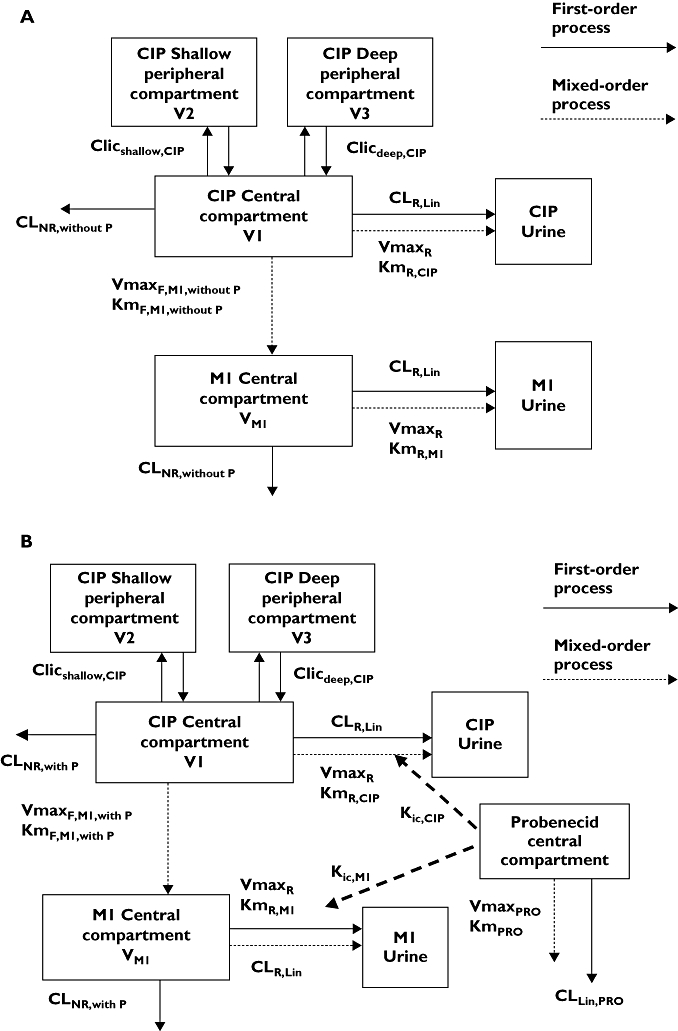

Figure 2.

Compartmental model. (a) Treatment without probenecid. (b) Treatment with probenecid

|

where CLR,lin is the first-order renal clearance (filtration clearance), and the second part of the equation describes the net tubular secretion. VmaxR is the maximum rate of the mixed-order renal elimination, KmR,CIP is the ciprofloxacin concentration associated with a half maximal rate (VmaxR/2) for the mixed-order renal elimination, and [C] is the plasma concentration of ciprofloxacin.

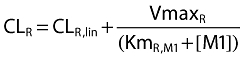

Since the NCA showed a significant reduction of renal clearance of M1 by probenecid, a parallel first-order and mixed-order renal clearance was assumed for M1. This is a physiologically reasonable way to describe the renal elimination of M1. The M1 concentrations were about 1/10th to 1/200th the ciprofloxacin concentrations and, therefore, probably far below the KmR for the mixed-order renal elimination. Therefore, we used the same parameter for the filtration clearance (CLR,lin) and VmaxR for the metabolite as for ciprofloxacin and estimated KmR,M1 for the metabolite. This yields the following equation for renal clearance of M1 (see also Figure 2):

|

where KmR,M1 is the M1 concentration associated with a half maximal rate (VmaxR) for the mixed-order renal elimination, and [M1] is the plasma concentration of M1.

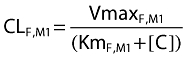

Formation of M1

The formation of M1 was studied as a first-order or mixed-order process. For models with first-order formation of M1, we described the formation of M1 by a first-order formation clearance CLF,M1. For mixed-order formation of M1, the following equation was used (see also Figure 2):

|

where VmaxF,M1 is the maximum rate of the mixed-order formation of M1, KmF,M1 is the ciprofloxacin concentration associated with a half maximal rate (VmaxR) for the mixed-order formation of M1, and [C] is the plasma concentration of ciprofloxacin.

Absorption and disposition of probenecid

One- and two-compartment disposition models with parallel first-order and mixed-order elimination pathways were considered for probenecid, since saturable elimination of probenecid has been reported previously [16, 17]. The oral absorption of probenecid was described as first-order process with or without a lag time.

Interaction models

The model assumed that the first-order renal elimination (glomerular filtration) of ciprofloxacin and M1 was not influenced by probenecid. Several plausible mechanisms were studied for the effect of probenecid on the renal tubular secretion of ciprofloxacin, renal tubular secretion of M1, and the formation of M1: competitive, uncompetitive, and noncompetitive inhibition (Table 1). Besides those three mechanisms, we also studied static interactions that were expressed either as two different nonrenal clearances for ciprofloxacin and M1 with (CLNR,with P) and without (CLNR,without P) probenecid, two different intercompartmental clearances for ciprofloxacin, two different volumes of distribution for M1, two different first-order formation clearances of M1, or different VmaxF,M1 and KmF,M1 for the formation of M1.

Table 1.

Mechanism of inhibition

| Type of inhibition | Inhibition constant | Apparent Km | Apparent Vmax |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive | Kic |  |

Vmax |

| Uncompetitive | Kiu |  |

|

| Noncompetitive | Ki | Km |  |

Vmax (mg h−1), maximum rate of the active transport process; Km (mg l−1), Michaelis–Menten constant, ciprofloxacin concentration at half Vmax; P (mg l−1), probenecid concentration; Kic (mg l−1), competitive inhibition constant, describes the affinity of probenecid to the drug transporter without ciprofloxacin; Kiu (mg l−1), uncompetitive inhibition constant, describes the affinity of probenecid to the transporter–ciprofloxacin complex; Ki (mg l−1), noncompetitive inhibition constant, represents the special case that probenecid binds to both the free transporter and the transporter–ciprofloxacin complex with the same affinity (i.e. Ki= Kic= Kiu).

Interaction models that comprised either a single interaction mechanism or a combination of interaction mechanisms for different interaction sites were studied. For the competitive interactions, the relative affinities (= ratio Kic/Km) of ciprofloxacin, M1 and probenecid to the transporter were calculated (Table 1), accounting for molecular weight. The molecular weight is 331 g mol−1 for ciprofloxacin base, 317 g mol−1 for M1 base, and 285 g mol−1 for probenecid base.

Statistical analysis

The noncompartmental and compartmental parameter estimates for ciprofloxacin and M1 were tested for differences between treatments (with and without probenecid). anova statistics on log scale and an α-level of significance of 0.05 were used.

Results

All 12 subjects completed the study. The average ± SD weight was 67.1 ± 12 kg, height was 175 ± 11 cm, and age was 28.5 ± 5.2 years. Plasma and urine profiles of ciprofloxacin and M1 with and without probenecid and probenecid concentrations in plasma are shown in Figure 1. Ciprofloxacin had about 10–200 times higher concentrations than the metabolite.

Figure 1.

Ciprofloxacin, ciprofloxacin-M1 and probenecid plasma concentrations and amounts in urine (average ± standard deviation). Lines represent average predicted concentrations and amounts in urine of the model with competitive interaction for renal elimination

Plasma concentrations of both ciprofloxacin and M1 were higher for the treatment with probenecid. The amount of ciprofloxacin excreted in urine was reduced by probenecid. The average amount of M1 excreted in urine was increased by probenecid; however, the variability of the amount of M1 in urine was high and therefore this increase was not statistically significant (Figure 1).

Noncompartmental analysis

Addition of probenecid reduced the median renal clearance from 23.8 to 8.25 l h−1 (reduction by 65%, P < 0.001) for ciprofloxacin, and from 20.5 to 8.26 l h−1 (reduction by 64%, P < 0.001) for M1 (Table 2). Therefore, total body clearance of ciprofloxacin was decreased by 42% (P < 0.001) with probenecid. Nonrenal clearance and volume of distribution at steady state of ciprofloxacin were not affected significantly by probenecid. The addition of probenecid resulted in peak concentrations in plasma that were slightly higher for ciprofloxacin and significantly higher for M1. In addition, the mean residence time was significantly prolonged (P < 0.001) for both ciprofloxacin (from 3.54 to 5.49 h) and M1 (from 6.30 to 9.18 h), and the half-life in plasma was significantly prolonged only for ciprofloxacin (from 4.95 to 5.80 h), but less affected for M1.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of ciprofloxacin and ciprofloxacin-M1 after ciprofloxacin was given alone or with probenecid derived from noncompartmental analysis (median [25% percentile–75% percentile] and ratio of geometric means (90% confidence interval)

| Ciprofloxacin | Ciprofloxacin metabolite (M1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average [95% CI] | Point estimate (90% CI) | Average [95% CI] | Point estimate (90% CI) | |||||

| With PRO | Without PRO | With PRO/without PRO | P-value | With PRO | Without PRO | With PRO/without PRO | P-value | |

| CLT (l h−1) | 21.8 [17.9–25.6] | 37.0 [31.8–42.2] | 58% (55, 61) | <0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| CLR (l h−1) | 8.12 [6.45–9.79] | 22.5 [19.4–25.5] | 35% (29, 41) | <0.001 | 8.10 [6.03–10.2] | 21.3 [18.5–24.1] | 36% (31, 42) | <0.001 |

| CLNR (l h−1) | 13.6 [10.5–16.7] | 14.5 [11.5–17.5] | 92% (84, 102) | 0.192 | – | – | – | – |

| AUCinf (mg l−1 h) | 9.90 [8.05–11.8] | 5.68 [4.81–6.56] | 172% (163, 181) | <0.001 | 0.710 [0.545–0.876] | 0.211 [0.166–0.255] | 329% (292, 372) | <0.001 |

| Ae (%) | 38.3 [31–45.6] | 61.2 [56.7–65.8] | 60% (51, 70) | <0.001 | 2.68 [1.85–3.50] | 2.19 [1.69–2.69] | 118% (99, 141) | 0.118 |

| Vss (l) | 123 [109–137] | 130 [118–142] | 94% (87, 101) | 0.169 | – | – | – | – |

| Cmax (mg l−1) | 5.46 [4.75–6.17] | 4.61 [3.82–5.40] | 120% (104, 140) | 0.047 | 0.0662 [0.047–0.086] | 0.0345 [0.025–0.044] | 187% (164, 213) | <0.001 |

| T1/2 (h) | 6.06 [5.10–7.02] | 4.63 [3.65–5.61] | 135% (119, 153) | 0.001 | 6.67 [5.29–8.05] | 5.83 [4.65–7.01] | 115% (90, 147) | 0.334 |

| MRT (h) | 5.94 [4.97–6.92] | 3.68 [3.06–4.29] | 162% (154, 171) | <0.001 | 9.84 [8.50–11.2] | 6.87 [5.87–7.88] | 143% (133, 155) | <0.001 |

CLT, total body clearance; CLR, renal clearance; CLNR, nonrenal clearance; AUCinf, area under the curve extrapolated to infinity; Ae, fraction excreted unchanged in urine; Vss, volume of distribution at steady state; Cmax, maximal plasma concentration; T1/2, terminal half-life in plasma; MRT, mean residence time for ciprofloxacin and mean body residence time for M1.

Compartmental modelling

Disposition of ciprofloxacin and probenecid

For the plasma and urine profiles of ciprofloxacin the three-compartment model was chosen based on the AIC and residuals analysis (Figure 2). For probenecid a one-compartment model with a lag time was selected.

Interaction of ciprofloxacin and probenecid

Modelling of ciprofloxacin and probenecid concentration–time profiles (without M1 data) suggested competitive inhibition of renal tubular secretion of ciprofloxacin by probenecid as the most likely mechanism. We selected this mechanism for the interaction at the renal site. The estimates for nonrenal clearance of ciprofloxacin were only slightly lower for the treatment with probenecid (Table 3). Therefore, we did not study a mechanistic model for an interaction of probenecid with ciprofloxacin on the nonrenal clearance. A static interaction with two different parameters for nonrenal clearance was included to account for the small reduction and for the between-occasion variability in nonrenal clearance.

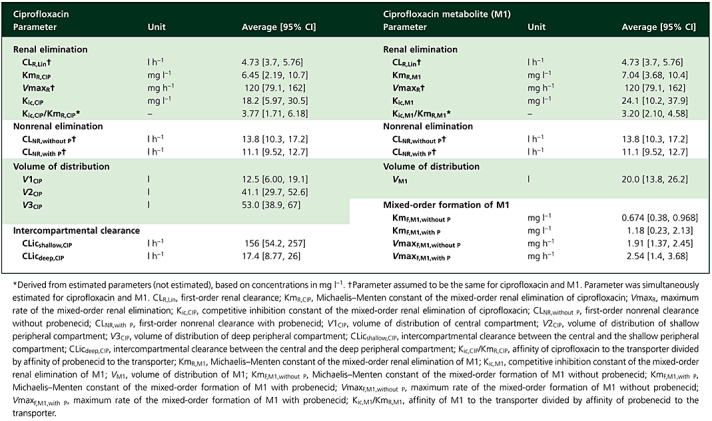

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameter estimates for ciprofloxacin and M1 derived from final compartmental model (see also Figure 2)

|

Disposition of M1

From the NCA it was observed that ciprofloxacin and M1 had similar terminal half-lives. The geometric mean of the ratio for terminal half-life(M1)/terminal half-life(ciprofloxacin) was 1.18 (34% coefficient of variation). In absence of data on the terminal half-life of M1 after i.v. dosing, it was assumed that the formation of the metabolite determined its terminal half-life. The flip-flop situation for M1 seems reasonable due to the similar terminal half-lives of parent and metabolite. The plasma concentration–time curves of the metabolite did not show two-compartment behaviour, which was in agreement with the formation of the metabolite being the rate-limiting step. Therefore, a one-compartment model was selected for M1 (Figure 2).

Formation of M1

Based on the ciprofloxacin and M1 data for the treatment without probenecid, a mixed-order process described the formation of the metabolite better than or equally well as a first-order formation process. More importantly, the Michaelis–Menten constant for the formation of the metabolite was about 0.6 mg l−1, which was well within the range of the ciprofloxacin plasma concentrations. Therefore, a mixed-order process was selected for the formation of the metabolite, which is also the physiologically most reasonable choice. Our models showed that probenecid did not affect the formation parameters of M1, since the parameters for the mixed-order formation of M1, VmaxF,M1 and KmF,M1 (Table 3) were not significantly affected by the addition of probenecid.

Interaction of M1 and probenecid

Various models were tested to describe the interaction between M1 and probenecid at the renal site. The AIC and residuals analysis suggested a competitive inhibition of renal tubular secretion as the most likely interaction mechanism between M1 and probenecid at the renal site.

As described in Methods, it was assumed that M1 had the same nonrenal clearance as ciprofloxacin (option iii) and the nonrenal clearance of ciprofloxacin and the metabolite was estimated simultaneously. Under this assumption, the volume of distribution of the metabolite was very similar for treatment with and without probenecid. Therefore, the same volume of distribution for M1 was used for both treatments in the final model. When assuming that the metabolite was only eliminated renally (option i), the volume of distribution of M1 was about 45% lower for treatment with probenecid relative to treatment without probenecid, and Vmax for the formation of M1 was reduced by about 40% under the influence of probenecid. Especially the reduction of volume of distribution would be a quite unreasonable result, because the volume of distribution of ciprofloxacin was unaffected by probenecid. Therefore, this was a strong indication that using the same nonrenal clearance for ciprofloxacin and M1 (option iii) was a more reasonable choice than assuming that nonrenal clearance was zero for M1 (option i).

Final model

A competitive inhibition of renal tubular secretion of ciprofloxacin by probenecid (model 1) was found to have the best AIC values for six of the 12 subjects and good AIC values in the other six subjects, and gave the best fit to our data. The other mechanisms of inhibition of renal tubular secretion were ranked less likely. Model 2 included noncompetitive inhibition of renal tubular secretion, had the best AIC values for three of the 12 subjects, and a 2.66-points worse average individual AIC compared with model 1. Model 3 included uncompetitive inhibition of renal tubular secretion, had the best AIC values for two of the 12 subjects, and a 0.82-point worse average individual AIC compared with model 1. Model 4 included competitive inhibition of renal tubular secretion and two different parameters for intercompartmental clearance for treatment with and without probenecid. Model 4 had the best AIC value for one of the 12 subjects, and a 2.47-points worse average individual AIC compared with model 1. Our models did not indicate any effect of probenecid on drug distribution. Neither the ciprofloxacin intercompartmental clearance nor the volume of distribution was affected by probenecid.

Figure 2 shows the compartmental structure of our final model and Table 3 lists the estimates for the PK parameters of ciprofloxacin and M1. Our final model included competitive inhibition of renal elimination of both ciprofloxacin and M1 by probenecid and described the formation of the metabolite as a mixed-order process. For the competitive interaction at the renal site the affinity of ciprofloxacin for the renal transporter was 3.8 times (median) higher than the affinity of probenecid and the affinity of M1 was 3.2 times higher than the affinity of probenecid, based on the competitive interaction model and the drug concentrations in mg l−1. As shown in Figure 1, probenecid reached about 100 times higher average plasma concentrations than ciprofloxacin and about 1600–2100 times higher average plasma concentrations than M1. After accounting for differences in molecular weight, the affinity of ciprofloxacin was 4.4-fold higher compared with probenecid, the affinity of M1 was 3.6 times higher than that of probenecid and probenecid reached about 120-fold higher molar concentrations. Therefore, probenecid inhibited renal tubular secretion of ciprofloxacin and M1 at the renal transporter to the extent shown in Table 2, although ciprofloxacin and M1 had a higher affinity to the transporter than probenecid.

Probenecid reduced the nonrenal clearance of ciprofloxacin only by 8% (see Table 2), which indicates that there was only a small (if any) inhibition of probenecid on the nonrenal clearance of ciprofloxacin.

Discussion

The interaction with probenecid has been studied for a long time and for many quinolones and β-lactams. Its extent may reach clinical significance for drugs that are actively secreted in the renal tubules [6, 18, 19]. For several quinolones, such as norfloxacin [9], fleroxacin [10], enoxacin [11], levofloxacin [7, 8] and gatifloxacin [6], a reduction in renal clearance with probenecid was found.

Although the extent of interaction with probenecid is known for several quinolones, little is known about the mechanism of interaction, site(s) of interaction, and the relative affinity of probenecid and quinolones. We are not aware of any reports where a mechanism-based model for the interaction of quinolones and probenecid in humans or animals has been developed. Therefore, we developed a model to describe adequately the plasma concentrations and amounts in urine of ciprofloxacin and its metabolite M1, including the formation of M1. Possible influences of probenecid on renal and nonrenal clearance, distribution of both ciprofloxacin and M1, and the formation of M1 were explored. In addition, we intended to propose a possible mechanism for the interaction between ciprofloxacin, M1 and probenecid at each site of interaction.

Studying the interaction between probenecid and both the parent compound ciprofloxacin as well as the biologically active CIP-M1 metabolite yields additional insights into the site of interaction. The piperazine ring is known to contribute in major parts to the PK properties of quinolones. This model system may be valuable for describing the site(s) of interactions of other drugs. As for ciprofloxacin, the time course of the renal interaction of M1 with probenecid was adequately described by competitive inhibition of renal tubular secretion by probenecid. Also, from the physiological point of view, competitive interaction seems the most reasonable one, as it describes the situation that ciprofloxacin and probenecid compete for the same active site of a renal transporter and that M1 and probenecid compete for the same active site of a renal transporter. Therefore, we chose competitive renal interaction between ciprofloxacin and probenecid, and between M1 and probenecid.

Modelling suggested that the affinity of ciprofloxacin for the renal transporter was 3.8 times (median) higher than the affinity of probenecid, and the affinity of M1 was 3.2 times (median) higher than of probenecid based on the concentrations in mg l−1 (Table 3). The ratios of the relative affinity of ciprofloxacin to the transporter and of M1 to the transporter within the individual subjects were close to 1 (median 0.99). This suggests that ciprofloxacin and M1 are probably secreted by the same renal tubular transporter(s).

For the formation of M1 a first-order or mixed-order process was considered. The Michaelis–Menten constant for the formation of M1 (KmF,M1,without P, see Table 3) was estimated to be about 0.5–0.6 mg l−1 and was about 1/10th the peak concentrations of ciprofloxacin. The ciprofloxacin concentrations were > 0.5 mg l−1 for about 3 h when ciprofloxacin was given alone and for about 6 h for ciprofloxacin plus probenecid. The plasma concentration profiles of M1 showed broad, plateau-like peaks for the interaction treatment, which were probably caused by partial saturation of the formation of M1 at high ciprofloxacin concentrations. The model with first-order formation does not account for saturation of metabolism. Consequently, the model with first-order formation over-predicted the peak concentrations of the metabolite, whereas the model with mixed-order formation of M1 described the plasma and urine data of M1 for both treatments very well.

In our final model, the parameters for the mixed-order formation of M1 were allowed to vary between both treatments to account for between-occasion variability. The estimates for KmF,M1,without P and KmF,M1,with P as well as for VmaxF,M1,without P and VmaxF,M1,with P were similar (P > 0.05) for both treatments (Table 3). The ratio of Vmax/Km, which represents the formation clearance of M1 at low ciprofloxacin concentrations, was 3.0 (0.72–13.9) l h−1 for ciprofloxacin alone and 3.1 (0.75–9.0) l h−1 for ciprofloxacin with probenecid [median (range)]. Consequently, it was not surprising that models with competitive or noncompetitive inhibition of probenecid on the formation of M1 were not supported by the data. Therefore, modelling indicated that probenecid did not influence the formation of M1.

NCA was an adequate method to study the extent of inhibition of renal clearance of ciprofloxacin and M1 as well as of nonrenal clearance of ciprofloxacin by probenecid. However, standard NCA cannot predict the extent of interaction at other than the studied dose level, and it would be very difficult, if not impossible, to draw a conclusion about the influence of probenecid on the formation of M1. Furthermore, standard NCA is not an adequate method to study a possible influence of probenecid on the volume of distribution of ciprofloxacin.

There is also no direct way to suggest a mechanism of interaction by NCA based on the available data, because standard NCA does not account for the time course of interaction. Given these limitations of NCA, compartmental analysis appeared as a much more powerful method for data analysis of this interaction study. We combined all features of the PK model in our final model, which included competitive inhibition of renal tubular secretion of ciprofloxacin and M1 by probenecid as well as the saturable formation of M1.

It was necessary to make an assumption about the nonrenal clearance of M1 to retain identifiability of the PK model. When it was assumed that nonrenal clearance of the metabolite was zero, the volume of distribution of M1 would have been decreased by about 45% by probenecid and probenecid would have reduced the rate of formation of the metabolite by about 40%. As there was no decrease in volume of distribution for ciprofloxacin, such an effect of probenecid on M1 seemed unlikely. When assuming that ciprofloxacin and M1 had the same nonrenal clearance, volume of distribution for M1 became very similar for both treatments and there was no effect of probenecid on the formation of M1. Therefore, our analysis could show that probenecid did not influence the volume of distribution for ciprofloxacin and, most likely, also did not influence volume of distribution of M1 (on the basis of a semi-empirical choice).

Our models also indicated that probenecid did not affect the intercompartmental clearance of ciprofloxacin. Consequently, probenecid did not alter the drug distribution of ciprofloxacin. Besides the ability of compartmental modelling to draw those mechanistic conclusions on the interaction of ciprofloxacin, M1 and probenecid, probably the most important advantage of compartmental analysis over NCA is the ability of our final compartmental model to predict the extent and time course of the interaction for other dose levels.

While compartmental modelling by the standard two-stage approach has considerable advantages over noncompartmental analysis, as discussed above, further value might be added to the analysis by application of the population approach. While use of the standard two-stage approach is a limitation of this study, our study design included a rich sampling schedule for multiple matrices in all subjects; therefore, sufficient information was available from each subject to fit the individual concentration–time profiles. The objective of the present analysis was to develop a mechanism-based model and obtain estimates of the average PK parameters, whereas the estimation of between-subject variability was not the main objective in this analysis. Also the value of estimates of between-subject variability would be limited by the small sample size in the study.

Population analysis can avoid potential bias in the parameter estimates due to a notable number of samples below the quantification limit (left-censoring of the data). However, potential bias due to a censoring pattern in the concentration measurements is of minor concern in this study, as only 1.4% of all samples were below the limit of quantification and as multiple matrices (including urine) were available for all subjects in this study.

For PD simulations, which were not performed in this analysis, generally a full population PK analysis would be preferred. However for the current objectives, investigating the many different mechanism-based models by population PK modelling would take extensive computation time, which was not justified by the added value of the population analysis in this case.

Knowledge of transport proteins and their substrate specificity has increased considerably during the last decade(s) [20]. Organic anion transporters (OAT) and organic cation transporters (OCT) are involved in active renal secretion of numerous drug molecules [5] and have been found also at various other sites in the body. Probenecid has been reported to interact with both [21, 22]. Ciprofloxacin is eliminated by the kidneys by glomerular filtration and tubular secretion and shows only a negligible extent of tubular reabsorption [23]. Unbound renal clearance of ciprofloxacin is much higher than creatinine clearance, which also implies net tubular secretion. As a zwitterion at physiological pH values (pKa1= 6.1, pKa2= 8.7), ciprofloxacin might also be able to interact with both OAT and OCT [23]. Cimetidine, an inhibitor of OCT as well as OAT 1 and 3 [24–26], has been shown to decrease the renal clearance of several quinolones, e.g. gemifloxacin, enoxacin, temafloxacin and ofloxacin [27, 28].

OAT1 has been suggested as a possible candidate for the renal interaction between ciprofloxacin and probenecid, as OAT1 is inhibited by probenecid [29]. Cinoxacin inhibited the uptake of p-aminohippuric acid by OAT1, whereas ofloxacin and norfloxacin showed no interaction [30]. VanWert et al. found that ciprofloxacin was transported by OAT3 and ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, ofloxacin and gatifloxacin inhibited OAT3 [31]. Ciprofloxacin did not interact with OAT1, while probenecid inhibits both OAT1 and OAT3 [31, 32]. Also, involvement of OCT was reported for ciprofloxacin [31] as for probenecid. Therefore an OAT, e.g. OAT3, or OCT might be the site of interaction between ciprofloxacin and probenecid.

Further studies are required to identify which transporter(s) are involved in the interaction between quinolones and probenecid. Information about renal transport processes of quinolones can help to explore potential toxicities due to co-administration of quinolones with other drugs, such as methotrexate [31].

From modelling alone no conclusions can be drawn about which particular transporters are involved in the studied interaction; however, the extent of the interaction can be predicted for other than the studied dosage regimens. As drug interactions at tubular secretion are frequently reported, our model can be useful also for other drugs and drug groups.

In conclusion, our compartmental analysis has shown that the profiles of ciprofloxacin, M1 and probenecid in plasma and urine could be well described by competitive inhibition of renal tubular secretion of ciprofloxacin and M1 by probenecid. The affinities to the renal transporter were similar for the parent drug and metabolite, and were 4.4 and 3.6 times higher for ciprofloxacin and M1 than for probenecid, based on the molar ratio. Probenecid inhibited the secretion of ciprofloxacin, because plasma concentrations of probenecid were about 100 times higher than for ciprofloxacin and about 1600–2100 times higher than for M1. The formation of M1 was best described by a mixed-order process. The formation of M1, nonrenal clearance and volume of distribution of ciprofloxacin and M1, as well as the intercompartmental clearance of ciprofloxacin were not affected by probenecid. Simultaneous modelling of plasma and urine data of ciprofloxacin, M1 and probenecid was a powerful method to study the interaction of ciprofloxacin and M1 with probenecid at various possible interaction sites. Future studies for other quinolones are required to explore further the mechanism of interaction for probenecid in vivo.

Competing interests

None to declare.

Part of this work has been presented as a poster at the 15th Annual Meeting of the Population Approach Group in Europe (PAGE), Brugge, Belgium, 14–16 June 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eliopoulos GM, Gardella A, Moellering RC., Jr In vitro activity of ciprofloxacin, a new carboxyquinoline antimicrobial agent. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;25:331–5. doi: 10.1128/aac.25.3.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ullrich KJ, Rumrich G, David C, Fritzsch G. Bisubstrates: substances that interact with both, renal contraluminal organic anion and organic cation transport systems. II. Zwitterionic substrates: dipeptides, cephalosporins, quinolone-carboxylate gyrase inhibitors and phosphamide thiazine carboxylates; nonionizable substrates: steroid hormones and cyclophosphamides. Pflugers Arch. 1993;425:300–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00374180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamali F. The effect of probenecid on paracetamol metabolism and pharmacokinetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;45:551–3. doi: 10.1007/BF00315313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamali F, Rawlins MD. Influence of probenecid and paracetamol (acetaminophen) on zidovudine glucuronidation in human liver in vitro. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1992;13:403–9. doi: 10.1002/bdd.2510130603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gisclon LG, Boyd RA, Williams RL, Giacomini KM. The effect of probenecid on the renal elimination of cimetidine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1989;45:444–52. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1989.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakashima M, Uematsu T, Kosuge K, Kusajima H, Ooie T, Masuda Y, Ishida R, Uchida H. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of AM-1155, a new 6-fluoro-8-methoxy quinolone, in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2635–40. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fish DN, Chow AT. The clinical pharmacokinetics of levofloxacin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32:101–19. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199732020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaitonde M, Mendes P, House ESA, Lehr KH. The Effects of Cimetidine and Probenecid on the Pharmacokinetics of Levofloxacin. Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Francisco, 1995.

- 9.Shimada J, Yamaji T, Ueda Y, Uchida H, Kusajima H, Irikura T. Mechanism of renal excretion of AM-715, a new quinolonecarboxylic acid derivative, in rabbits, dogs, and humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983;23:1–7. doi: 10.1128/aac.23.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiba K, Saito A, Shimada J, Hori S, Kaji M, Miyahara T, Kusajima H, Kaneko S, Saito S, Ooie T, Uchida T. Renal handling of fleroxacin in rabbits, dogs, and humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:58–64. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wijnands WJ, Vree TB, Baars AM, van Herwaarden CL. Pharmacokinetics of enoxacin and its penetration into bronchial secretions and lung tissue. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988;21(Suppl. B):67–77. doi: 10.1093/jac/21.suppl_b.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stass H, Sachse R. Effect of probenecid on the kinetics of a single oral 400 mg dose of moxifloxacin in healthy male volunteers. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40(Suppl. 1):71–6. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimada J, Nogita T, Ishibashi Y. Clinical pharmacokinetics of sparfloxacin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1993;25:358–69. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199325050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaehde U, Sorgel F, Reiter A, Sigl G, Naber KG, Schunack W. Effect of probenecid on the distribution and elimination of ciprofloxacin in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1995;58:532–41. doi: 10.1016/0009-9236(95)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landersdorfer C, Kirkpatrick CM, Kinzig-Schippers M, Bulitta J, Holzgrabe U, Sorgel F. New insights into the most commonly studied drug interaction with antibiotics: pharmacokinetic interaction between ciprofloxacin, gemifloxacin and probenecid at renal and non-renal sites. 15th Annual Meeting of the Population Approach Group in Europe (PAGE), Brugge, Belgium, 2006.

- 16.Emanuelsson BM, Beermann B, Paalzow LK. Non-linear elimination and protein binding of probenecid. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;32:395–401. doi: 10.1007/BF00543976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vree TB, Van Ewijk-Beneken Kolmer EW, Wuis EW, Hekster YA. Capacity-limited renal glucuronidation of probenecid by humans. A pilot Vmax-finding study. Pharm Weekbl Sci. 1992;14:325–31. doi: 10.1007/BF01977622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garton AM, Rennie RP, Gilpin J, Marrelli M, Shafran SD. Comparison of dose doubling with probenecid for sustaining serum cefuroxime levels. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:903–6. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.6.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vlasses PH, Holbrook AM, Schrogie JJ, Rogers JD, Ferguson RK, Abrams WB. Effect of orally administered probenecid on the pharmacokinetics of cefoxitin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;17:847–55. doi: 10.1128/aac.17.5.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masereeuw R, Russel FG. Mechanisms and clinical implications of renal drug excretion. Drug Metab Rev. 2001;33:299–351. doi: 10.1081/dmr-120000654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meier PJ, Eckhardt U, Schroeder A, Hagenbuch B, Stieger B. Substrate specificity of sinusoidal bile acid and organic anion uptake systems in rat and human liver. Hepatology. 1997;26:1667–77. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shitara Y, Sato H, Sugiyama Y. Evaluation of drug–drug interaction in the hepatobiliary and renal transport of drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:689–723. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorgel F, Bulitta J, Kinzig-Schippers M. How well do gyrase inhibitors work? The pharmacokinetics of quinolones. Pharm Unserer Zeit. 2001;30:418–27. doi: 10.1002/1615-1003(200109)30:5<418::AID-PAUZ418>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burckhardt BC, Brai S, Wallis S, Krick W, Wolff NA, Burckhardt G. Transport of cimetidine by flounder and human renal organic anion transporter 1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F503–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00290.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tahara H, Kusuhara H, Endou H, Koepsell H, Imaoka T, Fuse E, Sugiyama Y. A species difference in the transport activities of H2 receptor antagonists by rat and human renal organic anion and cation transporters. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:337–45. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.088104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erdman AR, Mangravite LM, Urban TJ, Lagpacan LL, Castro RA, de la Cruz M, Chan W, Huang CC, Johns SJ, Kawamoto M, Stryke D, Taylor TR, Carlson EJ, Ferrin TE, Brett CM, Burchard EG, Giacomini KM. The human organic anion transporter 3 (OAT3; SLC22A8): genetic variation and functional genomics. Am J Physiol. 2006;290:F905–12. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00272.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stein GE. Drug interactions with fluoroquinolones. Am J Med. 1991;91:81S–86S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90316-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen A, Bird N, Dixon R, Hickmott F, Pay V, Smith A, Stahl M. Effect of cimetidine on the pharmacokinetics of oral gemifloxacin in healthy volunteers. Clin Drug Invest. 2001;21:519–26. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mizuno N, Niwa T, Yotsumoto Y, Sugiyama Y. Impact of drug transporter studies on drug discovery and development. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:425–61. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jariyawat S, Sekine T, Takeda M, Apiwattanakul N, Kanai Y, Sophasan S, Endou H. The interaction and transport of beta-lactam antibiotics with the cloned rat renal organic anion transporter 1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:672–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vanwert AL, Srimaroeng C, Sweet DH. Organic anion transporter 3 (oat3/slc22a8) interacts with carboxyfluoroquinolones, and deletion increases systemic exposure to ciprofloxacin. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:122–31. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.042853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burckhardt BC, Burckhardt G. Transport of organic anions across the basolateral membrane of proximal tubule cells. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;146:95–158. doi: 10.1007/s10254-002-0003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]