Abstract

AIMS

To investigate the inhibition potential and kinetic information of noscapine to seven CYP isoforms and extrapolate in vivo noscapine-warfarin interaction magnitude from in vitro data.

METHODS

The activities of seven CYP isoforms (CYP3A4, CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2E1, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C8) in human liver microsomes were investigated following co- or preincubation with noscapine. A two-step incubation method was used to examine in vitro time-dependent inhibition (TDI) of noscapine. Reversible and TDI prediction equations were employed to extrapolate in vivo noscapine–warfarin interaction magnitude from in vitro data.

RESULTS

Among seven CYP isoforms tested, the activities of CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 were strongly inhibited with an IC50 of 10.8 ± 2.5 µm and 13.3 ± 1.2 µm. Kinetic analysis showed that inhibition of CYP2C9 by noscapine was best fit to a noncompetitive type with Ki value of 8.8 µm, while inhibition of CYP3A4 by noscapine was best fit to a competitive manner with Ki value of 5.2 µm. Noscapine also exhibited TDI to CYP3A4 and CYP2C9. The inactivation parameters (KI and kinact) were calculated to be 9.3 µm and 0.06 min−1 for CYP3A4 and 8.9 µm and 0.014 min−1 for CYP2C9, respectively. The AUC of (S)-warfarin and (R)-warfarin was predicted to increase 1.5% and 1.1% using Cmax or 0.5% and 0.4% using unbound Cmax with reversible inhibition prediction equation, while the AUC of (S)-warfarin and (R)-warfarin was estimated to increase by 110.9% and 48.9% using Cmax or 41.8% and 32.7% using unbound Cmax with TDI prediction equation.

CONCLUSIONS

TDI of CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 by noscapine potentially explains clinical noscapine–warfarin interaction.

Keywords: cytochrome P450 (CYP), drug–drug interaction, noscapine, time-dependent inhibition, warfarin

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Clinical cases reported to the Swedish adverse drug interactions register (SWEDIS) indicated that drug–drug interaction (DDI) existed when warfarin was co-administered with noscapine.

In vitro testing with recombinant human enzyme showed that noscapine inhibited CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 with an IC50 of around 1 µm.

However, the clinical relevance of these in vitro data remains to be explored.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Noscapine was demonstrated to be both a reversible inhibitor and a time-dependent inhibitor to CYP3A4 and CYP2C9.

DDI magnitude predicted from reversible inhibition and time-dependent inhibition (TDI) kinetic parameters showed that the TDI might be a noteworthy factor resulting in clinical noscapine–warfarin interaction.

Introduction

Noscapine, a phthalideisoquinoline alkaloid isolated from opium, has been widely used as an antitussive drug [1]. In recent years, noscapine has drawn more and more attention due to its excellent anticancer activity and low toxicity [2–4]. Noscapine is now in Phase I/II clinical trials as a chemotherapy agent to treat non-Hodgkin's lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukaemia [5].

Recently, there have been 12 clinical cases of the interaction between noscapine and warfarin reported to the Swedish adverse drug interactions register [6, 7]. These reports showed that serious adverse drug response (bleeding or increased International Normalized Ratio) occurred when warfarin was co-administered with noscapine. Results from in vitro testing with recombinant human enzyme demonstrated that noscapine inhibited CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 with an IC50 of around 1 µm[6], and attempted to link inhibition of CYP isoforms by noscapine to clinical noscapine–warfarin interaction. However, in vitro–in vivo extrapolation of metabolic noscapine–warfarin interaction magnitude can not be achieved due to lack of information on inhibition type and kinetic parameters. Thus, the aim of this study is to investigate the inhibition potential and kinetic information of noscapine to seven major CYP isoforms and extrapolate in vivo noscapine–warfarin interaction magnitude from in vitro inhibition kinetic data.

Methods

Preparation and characterization of human liver microsomes

Human livers were obtained from autopsy samples (n= 9, male Chinese, aged 27–48 years) from Dalian Medical University (Dalian, China), with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Dalian Medical University. The medication history of the donors was not known. Research involving human subjects was performed under full compliance with government policies and the Helsinki Declaration.

Microsomes were prepared from liver tissue by differential ultracentrifugation [8]. Protein concentrations of the microsomal fractions were determined by the method of Lowry et al. using bovine serum albumin as a standard [9]. The determination of CYPs content was performed according to the method of Omura and Sato [10].

CYP probe substrate assays

Human liver microsomal phenacetin O-deethylation, coumarin 7-hydroxylation, paclitaxel 6α-hydroxylation, diclofenac 4′-hydroxylation, dextromethorphan O-demethylation, chlorzoxazone 6-hydroxylation and testosterone 6β-hydroxylation activities were used as probe reactions for CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP2E1 and CYP3A4. Briefly, the incubation system contained 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-generating system (1 mm NADP+, 10 mm glucose-6-phosphate, 1 U ml−1 of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, and 4 mm MgCl2), appropriate concentration of human liver microsomes (HLM), respective probe substrate and noscapine (or positive control inhibitor) in a final volume of 200 µl. After 3 min preincubation at 37°C, the reaction was initiated by adding NADPH-generating system and terminated by adding 100 µl acetonitrile (10% trichloroacetic acid for CYP2A6) with internal standard. The incubation conditions including substrate and protein concentration, incubation time, internal standard, and high-performance liquid chromatography conditions have been reported [11].

Enzyme inhibition experiments

To evaluate the inhibitory effect of noscapine toward seven different human CYP isoforms, marker assays for each CYP isoform were performed in the presence of 100 µm noscapine. The concentrations of positive inhibitors used were as follows: 10 µm furafylline for CYP1A2, 2.5 µm 8-methoxypsoralen for CYP2A6, 1 µm ketoconazole for CYP3A4, 10 µm sulfaphenazole for CYP2C9, 10 µm quinidine for CYP2D6, 50 µm clomethiazole for CYP2E1, and 5 µm montelukast for CYP2C8. For CYP isoforms that were strongly inhibited, half inhibition concentration (IC50) values were determined using various concentrations of noscapine (50, 20, 10, 5, 2, 1, 0.5, 0.2, 0 µm for CYP3A4 and 100, 50, 20, 10, 5, 2, 1, 0 µm for CYP2C9) as previously reported [12]. The Ki value was obtained by incubating various probe substrates (5–30 µm diclofenac and 30–100 µm testosterone) and 0–50 µm noscapine.

Single point inactivation experiments

Single point inactivation experiments were used to determine NADPH-dependent and preincubation-dependent inhibition of noscapine, as previously reported [13]. In brief, pooled HLMs (1 mg ml−1) were incubated with noscapine in the absence and presence of NADPH-generating system for 30 min at 37°C. For CYP3A4 and CYP2C9, the concentration of noscapine utilized was 10-fold that which gave 25% inhibition under reversible inhibition situations. For other CYP isoforms, 50 µm of noscapine was used. After incubation, an aliquot (20 µl) was transferred to another incubation tube (final volume 200 µl) containing an NADPH-generating system and probe substrates whose concentrations were proximal to Km values. Further incubations were carried out to measure residual activity.

Estimation of inactivation constants

To determine the KI and kinact values for the inactivation of CYP3A4 and CYP2C9, six concentrations of noscapine (0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 50 µm) were incubated for 0–20 min with pooled HLMs (1 mg ml−1) at 37°C. After preincubation, an aliquot (20 µl) was transferred to another incubation tube (final volume 200 µl) containing an NADPH-generating system and 400 µm testosterone (for CYP3A4) or 40 µm diclofenac (for CYP2C9) to measure residual activity. Four times the Km concentration of substrates was selected to minimize the reversible inhibition caused by noscapine. To determine kobs (observed inactivation rate) values, the decrease in natural logarithm of activity over time was plotted for each noscapine concentration, and kobs values were described as the negative slopes of the line. Inactivation kinetic parameters were calculated using nonlinear regression of the data according to the Equation 1:

|

(1) |

| (2) |

|

(3) |

where [I] is the initial inhibitor concentration, kinact is the maximal inactivation rate constant and KI is the inhibitor concentration required for half the maximal rate of inactivation. The unbound KI (KI,u) was calculated according Equation 2, where fu,m is the free fraction of noscapine in the microsomes. fu,m is predicted according to Equation 3 as previously reported [14]. The terms are defined as follows: Cmic is the microsomal protein concentration used in the preincubation, and LogP is the log of the octanol-buffer (pH = 7.4) partition (P) coefficient of the noscapine. The concentration of 1 mg ml−1 was used for Cmic in this experiment, and LogP is approximately 2 according to the literature [15]. Thus, fu,m is calculated to be close to 66%.

Prediction of interaction between noscapine and warfarin

Equations 4 and 5 were used to predict interaction between noscapine and (S)-warfarin caused by reversible inhibition and time-dependent inhibition (TDI) of CYP2C9 by noscapine, and Equations 6 and 7 were utilized to predict the interaction between noscapine and (R)-warfarin caused by reversible inhibition and TDI of CYP3A4 by noscapine. All the equations were adapted according to previously reported ones [13, 16]:

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

The terms are defined as follows: AUCi/AUC is the predicted ratio of in vivo exposure of (S)-warfarin or (R)-warfarin with co-administration of noscapine vs. that in control situation, fm(CYP2C9) is the portion of total clearance of (S)-warfarin to which CYP2C9 contributes, fm(CYP3A4) is the portion of total clearance of (R)-warfarin to which CYP3A4 contributes, kdeg(CYP2C9) and kdeg(CYP3A4) is the first-order rate constant of in vivo degradation of CYP2C9 and CYP3A4, kinact is the maximum inactivation rate constant, KI,u is the unbound KI, Ki is the reversible inhibition constant, [I]invivo is the in vivo concentration of noscapine. The values of fm(CYP2C9), kdeg(CYP2C9) and kdeg(CYP3A4) are 0.91, 0.00026 min−1 and 0.000321 min−1, respectively, according to the values used by Obach et al.[13]. The value of fm(CYP3A4) is calculated to be approximately 0.4 according to the literature [17, 18].

Results

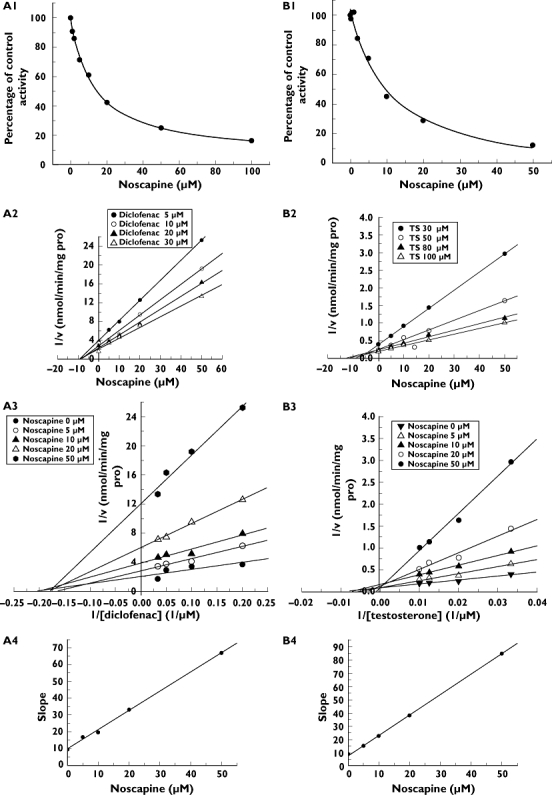

All positive control inhibitors performed strong inhibition to the corresponding probe reactions with >80% of control activity inhibited. The activities of CYP3A4, CYP2C9, CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2D6, CYP2C8 and CYP2E1 were inhibited by 100 µm of noscapine by 87.7, 83.7, 41.1, 30.8, 24.9, 48.8 and 0.2%, respectively. Further kinetic analysis was conducted for CYP3A4 and CYP2C9, whose activities were inhibited by >50%. As shown in Figure 1, noscapine inhibited diclofenac 4′-hydroxylation (CYP2C9) in a concentration-dependent manner with an IC50 of 13.3 ± 1.2 µm. Lineweaver–Burk and Dixon plots showed that the inhibition of noscapine to CYP2C9 was best fit to a noncompetitive way and the Ki value was calculated to be 8.8 µm from second plot of the slopes from Lineweaver–Burk plots vs. the concentrations of noscapine. The results also demonstrated that noscapine inhibited testosterone 6β-hydroxylation (CYP3A4) in a concentration-dependent manner with an IC50 of 10.8 ± 2.5 µm. Lineweaver–Burk and Dixon plots suggested that noscapine competitively inhibited CYP3A4 and the Ki value was evaluated to be 5.2 µm. Employing the above data and maximum concentration of noscapine (Cmax) after a single 50-mg oral dose (0.15 µm) [19], the AUC of (S)-warfarin and (R)-warfarin was predicted to increase by 1.5% and 1.1%, respectively. Considering the effect of human serum binding of noscapine (fu= 35% [20]), the AUC of (S)-warfarin and (R)-warfarin was predicted to increase by 0.5% and 0.4%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Reversible inhibition of noscapine to CYP3A4 and CYP2C9. (A1) Inhibition potential of noscapine to diclofenac 4′-hydroxylation activity (CYP2C9). (A2) Dixon plot of inhibition effect of noscapine on diclofenac 4′-hydroxylation activity (CYP2C9). (A3) Lineweaver–Burk plot of inhibition effect of noscapine on diclofenac 4′-hydroxylation activity (CYP2C9). (A4) Second plot of slopes from Lineweaver–Burk plot vs. noscapine concentrations. (B1) Inhibition potential of noscapine to testosterone 6β-hydroxylation activity (CYP3A4). (B2) Dixon plot of inhibition effect of noscapine on testosterone 6β-hydroxylation activity (CYP3A4). (B3) Lineweaver–Burk plot of inhibition effect of noscapine on 6β-hydroxylation activity (CYP3A4). (B4) Second plot of slopes from Lineweaver–Burk plot vs. noscapine concentrations

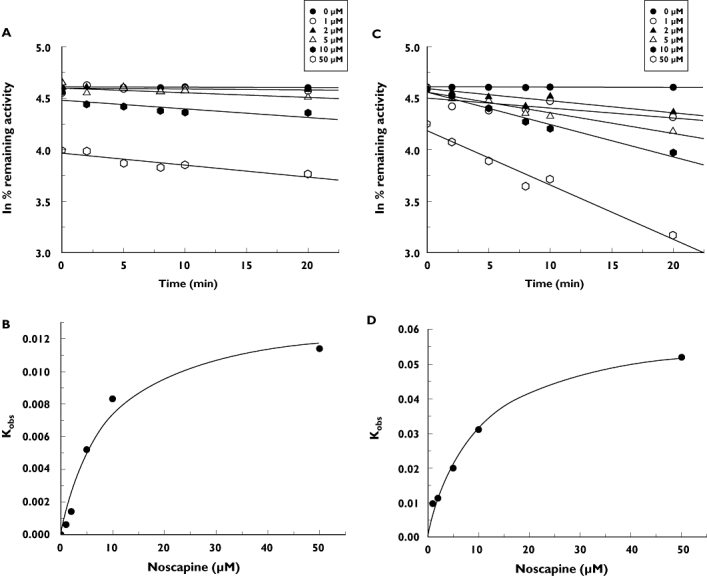

Time- and NADPH-dependent inhibitions were also evaluated. When noscapine was preincubated with HLM for 30 min in the presence of NADPH, the percentage of inhibition of CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 by noscapine was increased by 48.9% and 49.8%, respectively. However, the inhibition of other CYP isoforms by noscapine was not time- and NADPH-dependent (data not shown). As calculated from the observed inactivation plots (Figure 2), inactivation kinetic parameters (KI and kinact) were 9.3 µm and 0.06 min−1 for CYP3A4, and 8.9 µm and 0.014 min−1 for CYP2C9. KI,u was calculated to be 6.1 µm and 5.9 µm for CYP3A4 and CYP2C9, respectively. With KI,u, kinact and maximum concentration of noscapine (Cmax) after a single 50-mg oral dose (0.15 µm) [19], the AUC of (S)-warfarin and (R)-warfarin was calculated to increase by 110.9% and 48.9%, respectively. When the human serum binding of noscapine (fu= 35% [20]) was considered, the AUC of (S)-warfarin and (R)-warfarin was predicted to increase by 41.8% and 32.7%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Time-dependent inhibition of noscapine to CYP3A4 and CYP2C9. (a) Time- and concentration-dependent inhibition of CYP2C9 by noscapine. (b) The hyperbolic plot of kobs of CYP2C9 vs. noscapine concentrations. (c) Time- and concentration-dependent inhibition of CYP3A4 by noscapine. (d) The hyperbolic plot of kobs of CYP3A4 vs. noscapine concentrations

Discussion

Warfarin, a highly efficacious oral anticoagulant, occurs as a pair of enantiomers that experience extensive metabolism by human CYP isoforms. (R)-warfarin is mainly metabolized by CYP1A2 and CYP3A4, while (S)-warfarin, the pharmacologically more active enantiomer, is primarily metabolized by CYP2C9. Due to the narrow therapeutic window of warfarin, special attention should be paid to the magnitude of metabolic drug–drug interaction (DDI) with warfarin [17]. Previous investigations have shown that many drugs that inhibit CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 could augment the anticoagulant effect of warfarin [21, 22].

In the present study, we performed an in vitro experiment to predict the metabolic interaction magnitude between noscapine and warfarin. With the reversible inhibition model, the AUC of (S)-warfarin and (R)-warfarin was predicted to increase by 1.5% and 1.1% using Cmax or 0.5% and 0.4% employing unbound Cmax, which does not explain clinical noscapine–warfarin interaction. Nevertheless, when the TDI prediction model was selected to achieve risk assessment, the change of AUC in (S)-warfarin and (R)-warfarin was calculated to be 110.9% and 48.9% using Cmax or 41.8% and 32.7% employing unbound Cmax, which might offer a potential explanation for the case reports of clinical noscapine–warfarin interaction.

It should be noted that compounds with methylenedioxyphenyl groups have been reported to show mechanism-based inhibition (a subset of TDI) to cytochrome P450 via generation of cabene metabolites that can generate metabolite intermediate complex with CYP [23]. Noscapine contains methylenedioxyphenyl group. Thus, further biochemical mechanisms remain to be explored.

In conclusion, our results show that clinical reports on the DDI between noscapine and warfarin might be attributed to the TDI of noscapine to CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 with little contribution of reversible inhibition. Because patients with cancer are vulnerable to venous thromboembolism and need anticoagulant therapy, these findings are of importance for the development of noscapine as a new anticancer drug.

Competing interests

None to declare.

This work was supported by the 973 programme (2009CB522808) of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 30772608, 30973590). The authors wish to thank Dr Guohui Li for proof reading of our manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Empey DW, Laitinen LA, Young GA, Bye CE, Hughes DTD. Comparison of the antitussive effects of codeine phosphate 20 mg, dextromethorphan 30 mg and noscapine 30 mg using citric acid-induced cough in normal subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1979;16:393–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00568199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ye KQ, Ke Y, Keshava N, Shanks J, Kapp JA, Tekmal RR, Petros J, Joshi HC. Opium alkaloid noscapine is an antitumor agent that arrests metaphase and induces apoptosis in dividing cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1601–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landen JW, Han V, Wang MS, Davis T, Ciliax B, Wainer BH, Van Meir EG, Glass JD, Joshi HC, Archer DR. Noscapine crosses the blood–brain barrier and inhibits glioblastoma growth. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5187–201. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aneja R, Ghaleb AM, Zhou J, Yang VW, Joshi HC. p53 and p21 determine the sensitivity of noscapine-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3862–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aneja R, Dhiman N, Idnani J, Awasthi A, Arora SK, Chandra R, Joshi HC. Preclinical pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of noscapine, a tubulin-binding anticancer agent. Cancer Chemoth Pharm. 2007;60:831–9. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0430-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohlsson S, Holm L, Myrberg O, Sundstrom A, Yue QY. Noscapine may increase the effect of warfarin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:277–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scordo MG, Melhus H, Stjernberg E, Edvardsson AM, Wadelius M. Warfarin–noscapine interaction: a series of four case reports. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:448–50. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu HX, Liu Y, Zhang JW, Li W, Liu HT, Yang L. UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A6 is the major isozyme responsible for protocatechuic aldehyde glucuronidation in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:1562–9. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.020560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omura T, Sato R. The carbon monoxide-binding pigment of liver microsomes. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:2370–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang JW, Liu Y, Li W, Hao DC, Yang L. Inhibitory effect of medroxyprogesterone acetate on human liver cytochrome P450 enzymes. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:497–502. doi: 10.1007/s00228-006-0128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang YY, Liu Y, Zhang JW, Ge GB, Wang LM, Sun J, Yang L. Characterization of human cytochrome P450 isoforms involved in the metabolism of 7-epi-paclitaxel. Xenobiotica. 2009;39:283–92. doi: 10.1080/00498250802714907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obach RS, Walsky RL, Venkatakrishnan K. Mechanism-based inactivation of human cytochrome P450 enzymes and the prediction of drug–drug interactions. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:246–55. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.012633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Austin RP, Barton P, Cockroft SL, Wenlock MC, Riley RJ. The influence of nonspecific microsomal binding on apparent intrinsic clearance, and its prediction from physicochemical properties. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:1497–503. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.12.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ran YQ, He Y, Yang G, Johnson JLH, Yalkowsky SH. Estimation of aqueous solubility of organic compounds by using the general solubility equation. Chemosphere. 2002;48:487–509. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(02)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown HS, Ito K, Galetin A, Houston JB. Prediction of in vivo drug–drug interactions from in vitro data: impact of incorporating parallel pathways of drug elimination and inhibitor absorption rate constant. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:508–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaminsky LS, Zhang ZY. Human P450 metabolism of warfarin. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;73:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(96)00140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karjalainen MJ, Neuvonen PJ, Backman JT. Rofecoxib is a potent, metabolism-dependent inhibitor of CYP1A2: implications for in vitro prediction of drug interactions. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:2091–6. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.011965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karlsson MO, Dahlstrom B, Eckernas SA, Johansson M, Alm AT. Pharmacokinetics of oral noscapine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;39:275–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00315110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Idanpaan-Heikkila JE. Studies on fate of 3H-noscapine in mice and rats. Ann Med Exp Fenn. 1968;46:201–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolilekas L, Anagnostopoulos GK, Lampaditis I, Eleftheriadis I. Potential interaction between telithromycin and warfarin. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:1424–7. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi H, Kashima T, Kimura S, Murata N, Takaba T, Iwade K, Abe T, Tainaka H, Yasumori T, Echizen H. Pharmacokinetic interaction between warfarin and a uricosuric agent, bucolome: application of in vitro approaches to predicting in vivo reduction of (S)-warfarin clearance. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:1179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray M. Mechanisms of inhibitory and regulatory effects of methylenedioxyphenyl compounds on cytochrome P450-dependent drug oxidation. Curr Drug Metab. 2000;1:67–84. doi: 10.2174/1389200003339270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]