Abstract

Background

Concerns have been raised that many kidney donors do not receive adequate medical care after nephrectomy. In 2003, our program developed a policy recommending that donors have medical follow-up by 12 months post-nephrectomy. We hypothesized that medically complex donors would have a higher rate of follow-up than other donors.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study of 137 live kidney donors from a single center was performed. Donors were considered medically complex if they had hypertension, body mass index ≥ 30, nephrolithiasis, age ≥ 65 years, creatinine clearance <80 ml/min/1.73m2 or a 1st degree relative with diabetes. Adequate follow-up was defined as: 1) one visit with a nephrologist at our center, or 2) blood pressure, serum creatinine, and urinalysis checked elsewhere.

Results

83 donors (61%) had adequate follow-up, 42 did not, and 12 could not be contacted. In multivariate logistic regression, donors with adequate follow-up were more likely to be medically complex (O.R. 2.48, C.I. 1.18 - 5.23, p=0.017) and older than donors with inadequate follow-up (O.R. 1.46 per ten years of age, C.I. 1.01 - 2.10, p=0.044.)

Conclusions

A substantial minority of donors did not receive recommended care by 1 year following nephrectomy.

Introduction

Studies after live donor nephrectomy suggest that the long-term risk to the donor of developing end-stage renal disease is similar to the baseline risk in the general population.1-8 The apparent long-term safety of nephrectomy depends on careful screening prior to the procedure to identify healthy donors with excellent renal function and a low likelihood of developing progressive disease in the remaining kidney.9-11 Although certain medical conditions such as diabetes are contraindications to donor nephrectomy, donors with other risk factors for kidney disease such as well-controlled hypertension or obesity may be accepted by some centers.12-15 We refer to donors with medical risk factors for future kidney disease as “medically complex” live kidney donors.9

Surprisingly, while great efforts have been focused on identifying suitable donor candidates, few studies have been published on long-term management of donors after nephrectomy.16, 17 Since donors are left with reduced renal mass, periodic long-term monitoring has been recommended to screen for the development of complications or conditions that could affect the kidney.11, 18 A draft policy proposal regarding medical evaluation of live kidney donors, released for public comment by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) in July 2007, recommends guidelines that require transplant centers to follow live donors for two years following nephrectomy. The recommended follow-up includes, at a minimum, serum creatinine, urine protein and blood pressure at 6 months, 12 months and 24 months after discharge.19

Concerns have been raised that many kidney donors may not receive adequate medical care after nephrectomy.18, 20-22 Reasons for inadequate care may include a perceived sense of good health among donors, lack of access to health care, shortcomings in pre-donation counseling, or lack of consensus guidelines in the transplant community about the content, location and interval of follow-up after nephrectomy.8 In the United States, most recipients' insurance companies cover the donors' medical bills, but this coverage usually pertains to early post-nephrectomy care until donors have recovered from surgery. Once this phase of care is complete, donors are responsible for maintenance of long-term health issues through their own health insurance or private means.

In 2003, our transplant center, which typically performs 50 - 70 live donor kidney transplants per year, instituted a policy of recommending that donors have medical follow-up between 6 and 12 months post-nephrectomy, preferably on-site, and annually thereafter. The purpose of this retrospective cohort study was to assess donor adherence to medical follow-up recommendations by 1 year post-nephrectomy. We hypothesized that medically complex kidney donors would have a higher rate of adherence to follow-up care than non-complex donors.

Methods

We designed a retrospective cohort study of individuals who underwent donor nephrectomy at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania since the follow-up policy was established in 2003. To be eligible for the study, donors had to be at least 12 months status post nephrectomy. Our center does not accept live donors less than 18 years of age, prisoners or pregnant women. The project was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Donor characteristics at time of nephrectomy

We recorded donor age, gender, race, ethnicity, relation to recipient, whether donor lived at same address as recipient, whether donor had a primary care doctor and health insurance at nephrectomy, and the distance of home to the medical center in miles and minutes (obtained by entering home and center addresses into the internet site www.mapquest.com). Baseline clinical information about the donor included BMI, history of nephrolithiasis, clinical history of hypertension, blood pressure medications, blood pressure, 24 hour urine creatinine clearance, and family history of diabetes in a first degree relative. Operative information included type of nephrectomy (open versus laparoscopic), as well as development of post-operative complications. Post-operative “complication” was defined as length of stay greater than 4 days immediately post-operatively, or any of the following in the 2 weeks following surgery: wound healing problem, development of hypertension, creatinine increase greater than 50% over baseline, readmission, Emergency Department visit, or more than 1 call to transplant clinic prompting a charted note.

Criteria for donor medical complexity

As previously described, we classified donors as medically complex if they met any of the following criteria prior to nephrectomy: hypertension, body mass index (BMI)≥30, history of nephrolithiasis, age ≥ 65 years, creatinine clearance <80 ml/min/1.73m2 or a first degree relative with diabetes.9 Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure≥140mmHg or diastolic blood pressure≥90mmHg during pre-nephrectomy evaluation, a prior diagnosis with hypertension, or treatment with anti-hypertensive medications.23 Nephrolithiasis was defined as a prior medical history of ≥ 1 kidney stone or visualization of a stone on radiographic studies during the pre-donation workup. All donors underwent at least two 24 hour urine collections for measurement of creatinine clearance. We considered a donor to meet criteria for low creatinine clearance if two collections were <80 ml/min/1.73m2.24 A first degree relative was defined as a parent, sibling or child. All donors at our center are counseled about the possible long-term risk of developing chronic kidney disease.

Outcome of adequate medical follow-up

the binary outcome was defined as (1) seeing a nephrologist at our center, or (2) having blood pressure, serum creatinine and urinalysis checked by any medical professional. For the primary analysis, donors who did not follow-up at our institution and who could not be contacted by telephone were categorized as having inadequate follow-up.

Data collection

We determined demographic and medical information through review of: (1) the health system's medical records, (2) telephone calls to donors who did not either have adequate follow-up at our institution or send evidence of it to the transplant center.

Telephone follow-up

Using a scripted questionnaire, research personnel asked donors whether, during the approximate 6 - 12 month period after nephrectomy, they had undergone a blood pressure check, blood tests that measured kidney function such as serum creatinine, and a urinalysis. The questionnaire script provided donor with memory “cues,” including the date of their surgery and the period of one-year follow-up.25, 26 The script did not ask individuals to send copies of medical results. This phone questionnaire was reviewed for content validity with experts in questionnaire development and with transplant staff, including physicians and coordinators.27, 28 The questionnaire underwent numerous revisions on the basis of pilot-testing by phone with donors not included in the study.

Data management and statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using STATA (Stata 9.0, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX.) Descriptive variables were compared according to whether donors had adequate follow-up care. Normally distributed variables were compared across subgroups using the t-test. Categorical variables were compared across subgroups using chi-square, or by Fischer's exact when an individual cell size was less than five. A multivariate logistic regression model was fit with variables that had a significant unadjusted association (p<0.10) with adequate medical follow-up.

Sample size

Based on pilot data, we estimated that approximately 50% of non-medically complex donors would receive adequate follow-up care, and that the ratio of non-medically complex to medically complex donors would be 2:1. From a clinical standpoint, we decided that a 50% increase in the rate of follow-up care among medically complex donors compared to other donors would be an important and meaningful difference. Fixing alpha at 0.05 and beta at 0.8, we calculated that 132 donors total would be required.29

Results

The medical records of 139 consecutive live kidney donors were initially reviewed. One individual who had perished in a homicide was excluded. A second individual was later excluded during the telephone follow-up calls due to a language barrier (the donor spoke only an Eastern European language and we were unable to locate an appropriate translator). Thus, the final number of donors analyzed was 137.

Demographic characteristics

The demographic attributes of these 137 donors are displayed in Table 1. Fifty-six (41%) were male and the mean age was 39 years. Ninety-five donors (69%) were white, and 30 (22%) were black. One hundred twenty-one (88%) had health insurance and 124 (91%) had a primary care doctor at the time of donation. Sixty-one donors (45%) met criteria for being medically complex; forty-two of these 61 donors (69%) met criteria for complexity due to a family history of diabetes in a 1st degree relative. Eight had BMI≥30, 6 were hypertensive, 1 had a creatinine clearance<80 ml/min/1.73m2, and 4 had >1 criterion.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of live kidney donors at nephrectomy (n=137)

| Donor characteristic | Number |

|---|---|

| Mean age (standard deviation) | 39 years (1) |

| Male (%) | 56 (41) |

| Race (%) | |

| White | 95 (69) |

| Black | 30 (22) |

| Hispanic | 5 (4) |

| Asian | 5 (4) |

| Other | 2 (1) |

| Living related donor (%) | 85 (62) |

| Spousal donor (%) | 19 (14) |

| Median distance from center (miles) | 37 |

| Range | (1 - 2911) |

| Median distance from center (minutes) | 48 |

| Health insurance (%) | 121 (88) |

| Primary care doctor (%) | 124 (91) |

| Laparoscopic surgery (%) | 86 (63) |

| Medically complex (%) | 61 (45) |

| Family history diabetes | 42 |

| BMI≥30 | 8 |

| Hypertension | 6 |

| Low creatinine clearance | 1 |

| Combination of criteria | 4 |

| Age ≥ 65 years | 0 |

Distance from home to center was non-normally distributed. The median distance from the donor's home to the transplant center was 37 miles. After excluding a donor who lived outside the U.S., the mean distance was 235 +/- 597 miles (range 1 – 2911 miles). Due to the non-normal distribution of distance, this variable was log-transformed for univariate and multivariate analysis.

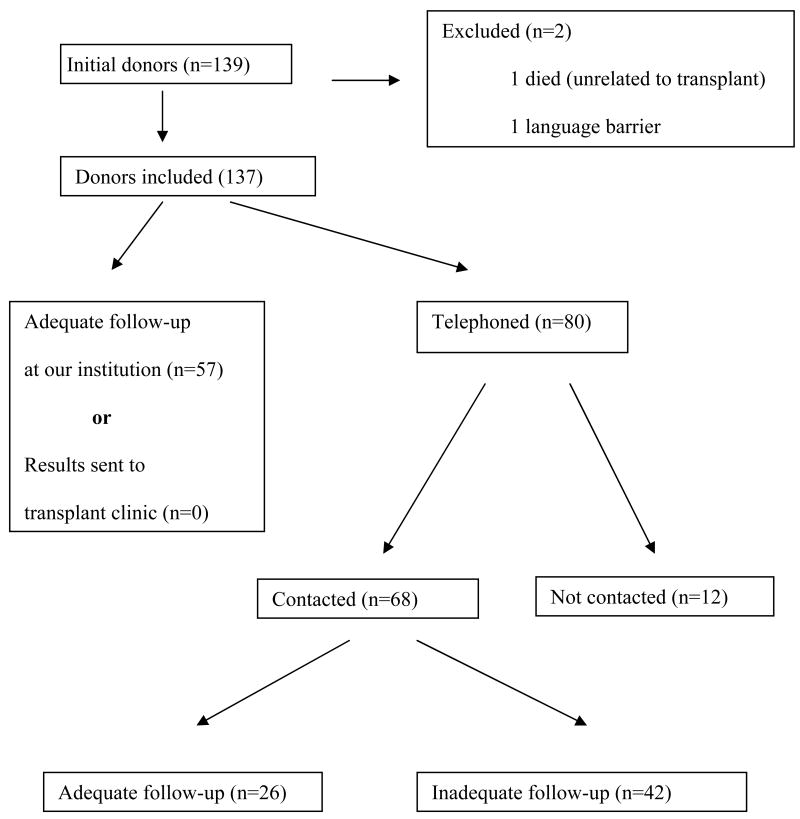

Follow-up data

As shown in Figure 1, 57 donors (42%) had adequate follow-up at our institution. The remaining 80 donors were telephoned and 68 were successfully contacted. Twelve donors could not be contacted despite repeated attempts, including by a transplant coordinator and a physician. Twenty-six of the donors that were contacted by telephone had adequate follow-up and 42 did not. Overall, therefore, 83 donors (61%) had confirmed adequate follow-up.

Figure 1.

Determination of donor follow-up

An examination of the group of 42 donors contacted by telephone who had inadequate follow-up revealed that only 9 had no medical follow-up at all. The rest of those reached by telephone with inadequate follow-up had seen a physician or physician extender by 1 year following nephrectomy but had not undergone all the surveillance studies recommended by our transplant center. Most of the donors who had medical follow-up outside our institution saw their primary care doctor.

The 12 donors that could not be contacted were less likely to be medically complex (OR 0.12, CI 0.00 - 0.79, p<0.02.) These donors had a mean age of 33.5 years versus 39.1 years for donors who could be contacted, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.059.) (Data not shown in tables.)

Univariate analysis: results presented in Table 2

Table 2.

Univariate association of donor characteristics with adequate medical follow-up by 1 year after donor nephrectomy

| Donor characteristic (binary) | Odds ratio | Confidence interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 0.69 | 0.35 – 1.38 | 0.30 |

| Black race | 1.16 | 0.51 - 2.64 | 0.72 |

| Living related donor | 0.94 | 0.46-1.89 | 0.86 |

| Spousal donor | 1.99 | 0.69-5.65 | 0.21 |

| Health insurance | 1.88 | 0.32-11.1 | 0.53 |

| Primary care doctor | 1.70 | 0.44-6.51 | 0.44 |

| Laparoscopic surgery | 1.00 | 0.49 – 2.04 | 1.00 |

| Medical complexity | 2.82 | 1.37 – 5.78 | 0.005 |

| Donor characteristic (continuous) | Adequate follow-up | Inadequate follow-up | p-value |

| Age (mean years) | 40.7 | 37.0 | 0.043 |

| Distance from center (mean miles) | 178.4 | 321.0 | 0.039 |

| Logarithm of distance from center | 1.60 | 1.82 | 0.09 |

Donors with adequate follow-up were more likely to be medically complex (OR 2.82, CI 1.37 - 5.78, p=0.005) and older than donors with inadequate follow-up (mean age 40.7 years for adequate follow-up versus 37.0 years, p=0.043.) The log-transformed distance from home to center was smaller for donors with adequate follow-up versus those without, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (1.60 for those with adequate follow-up versus 1.82 for those without, p=0.09.)

No other donor characteristics were associated with the outcome.

Multivariate logistic regression: results presented in Table 3

Table 3.

Multivariate association of donor characteristics with adequate medical follow-up by 1 year after donor nephrectomy*

| Donor characteristic | Odds ratio | Confidence interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medically complex donor | 2.48 | 1.18 - 5.23 | 0.017 |

| Age at surgery (per 10 years) | 1.46 | 1.01 - 2.10 | 0.044 |

| Distance from center (logarithm of miles) | 0.65 | 0.40 - 1.08 | 0.095 |

Donors who could not be contacted were considered to have inadequate follow-up

Three donor characteristics were entered into the multivariate model: donor medical complexity, donor age, and log distance between the donor's home and the center. Donors with adequate follow-up were more likely to be medically complex (OR 2.48, CI 1.18 - 5.23, p=0.017) and older than donors with inadequate follow-up (OR 1.46 per ten years, C.I. 1.01 - 2.10, p=0.044.) Log distance was not significantly different across the two groups.

Sensitivity analysis

We employed sensitivity analysis to measure the effect on our outcome if we assumed that the 12 donors that could not be contacted did have adequate follow-up. With this new assumption, the total proportion of donors with adequate follow-up increased from 83 (60.6%) to 95 (69%). Multivariate logistic regression was performed with the same 3 terms as the original model. Assuming that these donors that could not be contacted had adequate follow-up, we found that log-distance was inversely associated with adequate medical follow-up (OR 0.59, CI 0.35 - 0.98, p=0.04.) Neither medical complexity (OR 1.48, CI 0.68 - 3.19, p=0.32) nor donor age (OR 1.23, CI 0.85 - 1.78, p=0.27) were significant. (Data not in tables.)

Discussion

This study is the first that we are aware of that measures the rate of medical follow-up care for live donors in the year following nephrectomy. Despite a center policy advocating follow-up care, we found that a substantial minority of donors did not receive all elements of recommended care. Medically complex and older donors were more likely to adhere to follow-up recommendations. Given the draft proposal by UNOS that requires the medical follow-up described in our study, these results are timely, but show that medical centers may need to invest in staff and resources to follow donor outcomes. (11, 18-19.)

Live organ donation involves a unique scenario in which the donor is exposed to risks including surgery and potential long-term morbidity in order to benefit another person. Due to a strong ethical imperative to protect live donors, transplant centers strive to identify donors in excellent health and to ensure high standards of care that minimize the potential for harm.24 Increasingly, UNOS and transplant professionals have argued that the responsibility of transplant centers extends to medical follow-up beyond the immediate post-surgical period.9, 11 Although this medical follow-up has not been proven to improve the health of live kidney donors, it is plausible that treatment of risk factors for renal injury such as hypertension or proteinuria could be beneficial.

In this study, the rate of follow-up among medically complex donors was higher than among donors that were not medically complex. This finding may be due to a greater emphasis on potential risk with these donors by transplant clinicians. It is important to note that the relative and absolute risk of future kidney disease with medically complex donors compared to other donors is not known. Nonetheless, the criteria for medical complexity represent factors that transplant staff at our center and elsewhere have identified as cause for concern that these donors might be at higher risk for developing chronic kidney disease in the future.9, 15, 21

We also found that increasing age was associated with follow-up care. This finding is consistent with other studies that show that donors tend to seek more medical care as they get older, often in response to development of age-related medical conditions.30, 31

A limitation of our study was our inability to obtain follow-up information on 12 donors. This difficulty in locating these donors, despite multiple attempts by transplant staff including a physician, is surprising but also an important finding given the UNOS policy proposal recommending that US centers monitor donor health for at least 2 years. The wide range in distances that donors traveled to our center (1 - 2911 miles), and the limited proportion of donors (42%) who sought follow-up care at our center, both demonstrate that monitoring donor health will require resource-intensive methods of communicating with donors remotely.

In our primary analysis, we assumed that none of the 12 donors that could not be contacted had adequate follow-up. Given concerns in the transplant community that donor health is not adequately monitored after nephrectomy, we felt that assigning “inadequate follow-up” status to these donors was a reasonable approach to estimating the possible magnitude of the problem.18, 20-22 Additionally, the fact that our study staff was unable to contact these donors despite repeated attempts suggested that these donors might be less likely than others to adhere to follow-up recommendations. We performed a secondary sensitivity analysis in which these donors that could not be contacted were assigned “adequate follow-up” status. In this analysis, our results changed: neither medical complexity nor increasing age remained significant, but distance from the center was significant.

Another potential shortcoming with regards to donors who did not follow-up at our center was our reliance on participant recall. As noted in the methods section, donors who were telephoned were not asked to provide evidence of their medical results; we did not contact their physicians. Even in the context of providing donors with memory cues, patient recall may not be entirely accurate.25 On the other hand, relying on donors to confirm follow-up with documentation would likely run the risk of underreporting of follow-up.

Our study was not powered to explore all donor attributes that may plausibly be related to follow-up. We did look for an association between lack of health insurance and follow-up, for instance, but the majority of donors in our study had health insurance, limiting our power to detect a difference between the groups who did and did not have adequate follow-up. Additionally, our single-center results may not be generalizable to donors at other centers. Our population of donors is, however, ethnically diverse and draws patients from well beyond a major metropolitan area.

Conclusion

This retrospective cohort study suggests that, in the context of a center policy recommending medical follow-up by one year post-nephrectomy, a substantial minority of donors do not receive recommended care. Donors who get post-nephrectomy care with a local physician also may not share this information with the transplant center. Our observations have important implications in the face of a recent draft policy proposed by UNOS in July 2007 regarding post-nephrectomy follow-up of living kidney donors.19 Centers in the United States and elsewhere may need to institute costly and resource-intensive practices to track health outcomes for their donors. Further studies are needed to examine follow-up care for donors beyond one year.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Dr. Reese is supported by NIH Grant K23 - DK078688-01

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Najarian JS, Chavers BM, McHugh LE, Matas AJ. 20 years or more of follow-up of living kidney donors. Lancet. 1992 Oct 3;340(8823):807–810. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92683-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fehrman-Ekholm I, Elinder CG, Stenbeck M, Tyden G, Groth CG. Kidney donors live longer. Transplantation. 1997 Oct 15;64(7):976–978. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199710150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fehrman-Ekholm I, Duner F, Brink B, Tyden G, Elinder CG. No evidence of accelerated loss of kidney function in living kidney donors: results from a cross-sectional follow-up. Transplantation. 2001 Aug 15;72(3):444–449. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200108150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellison MD, McBride MA, Taranto SE, Delmonico FL, Kauffman HM. Living kidney donors in need of kidney transplants: a report from the organ procurement and transplantation network. Transplantation. 2002 Nov 15;74(9):1349–1351. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200211150-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narkun-Burgess DM, Nolan CR, Norman JE, Page WF, Miller PL, Meyer TW. Forty-five year follow-up after uninephrectomy. Kidney Int. 1993 May;43(5):1110–1115. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gossmann J, Wilhelm A, Kachel HG, et al. Long-term consequences of live kidney donation follow-up in 93% of living kidney donors in a single transplant center. Am J Transplant. 2005 Oct;5(10):2417–2424. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakim RM, Goldszer RC, Brenner BM. Hypertension and proteinuria: long-term sequelae of uninephrectomy in humans. Kidney Int. 1984 Jun;25(6):930–936. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaston RS, Wadstrom J. Living Donor Kidney Transplantation. Oxford: Taylor and Francis; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reese P, Caplan A, Kesselheim A, Bloom R. Creating a Medical, Ethical and Legal Framework for Complex Living Kidney Donors. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2006;1(6):1148–1153. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02180606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis CL. Evaluation of the living kidney donor: current perspectives. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004 Mar;43(3):508–530. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delmonico F. A Report of the Amsterdam Forum On the Care of the Live Kidney Donor: Data and Medical Guidelines. Transplantation. 2005 Mar 27;79(6 Suppl):S53–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Textor SC, Taler SJ, Driscoll N, et al. Blood pressure and renal function after kidney donation from hypertensive living donors. Transplantation. 2004 Jul 27;78(2):276–282. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000128168.97735.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matas AJ. Transplantation using marginal living donors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006 Feb;47(2):353–355. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steiner R. How should we ethically select living kidney donors when they all are at risk? Am J Transplant. 2005 May;5(5):1172–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steiner RW. Risk appreciation for living kidney donors: another new subspecialty? Am J Transplant. 2004 May;4(5):694–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabolde M, Herve C, Moulin AM. Evaluation, selection, and follow-up of live kidney donors: a review of current practice in French renal transplant centres. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001 Oct;16(10):2048–2052. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.10.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rizvi SA, Naqvi SA, Jawad F, et al. Living kidney donor follow-up in a dedicated clinic. Transplantation. 2005 May 15;79(9):1247–1251. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000161666.05236.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abecassis M, Adams M, Adams P, et al. Consensus statement on the live organ donor. Jama. 2000 Dec 13;284(22):2919–2926. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.UNOS. Guidelines for the medical evaluation of living kidney donors (Living donor committee) [July 25 2007]; Policy proposals issued for public comment [ http://www.unos.org/PublicComment/pubcommentPropSub_208.pdf.

- 20.Organ Donation: Opportunities for Action. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ommen E, Winston J, Murphy B. Medical risks for living donors: absence of proof is not proof of absence. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2006 July;1:885–895. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00840306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zink S, Weinreib R, Sparling T, Caplan AL. Living donation: focus on public concerns. Clin Transplant. 2005 Oct;19(5):581–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2004.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. Jama. 2003 May 21;289(19):2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis CL, Delmonico FL. Living-donor kidney transplantation: a review of the current practices for the live donor. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005 Jul;16(7):2098–2110. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004100824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Streiner D, Norman G. Health Measurement Scales. 2nd. New York: Oxford; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coughlin SS. Recall bias in epidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(1):87–91. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miles M, H M. The qualitative researcher's companion. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDowell I, Newell C. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. Oxford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dupont W, Plummer W. PS power and sample size program. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1997;18:274. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(90)90005-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker DW, Sudano JJ, Durazo-Arvizu R, Feinglass J, Witt WP, Thompson J. Health insurance coverage and the risk of decline in overall health and death among the near elderly, 1992-2002. Med Care. 2006 Mar;44(3):277–282. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000199696.41480.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pleis JR, L-C M. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National health interview survey, 2005. Vital Health Stat. 2006;10(232) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]