Abstract

Lung cancer is the most frequent cause of cancer-related death in this country for men and women. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a family of small non-coding RNAs (approximately 21–25 nt long) capable of targeting genes for either degradation of mRNA or inhibition of translation. We identified aberrant expression of 41 miRNAs in lung tumor versus uninvolved tissue. MiR-133B had the lowest expression of miRNA in lung tumor tissue (28 fold reduction) compared to adjacent uninvolved tissue. We identified two members of the BCL-2 family of pro-survival molecules (MCL-1 and BCL2L2 (BCLw)) as predicted targets of miR-133B. Selective over-expression of miR-133B in adenocarcinoma (H2009) cell lines resulted in reduced expression of both MCL-1 and BCL2L2. We then confirmed that miR-133B directly targets the 3’UTRs of both MCL-1 and BCL2L2. Lastly, over-expression of miR-133B induced apoptosis following gemcitabine exposure in these tumor cells. To our knowledge, this represents the first observation of decreased expression of miR-133B in lung cancer and that it functionally targets members of the BCL-2 family.

Keywords: microRNA, apoptosis, lung cancer, chemotherapy, BCL2, MCL-1

Introduction

Lung cancer is leading cause of cancer related deaths in the United States among both men and women [1]. Analysis of the lung cancer genome and proteome has demonstrated that focusing on molecular heterogeneity within lung cancers may be a viable approach to identify and develop novel therapeutics. Aberrant expression of miRNAs in malignancy and their frequent location in fragile chromosomal regions suggests their importance to the pathogenesis of disease [2]. MicroRNAs (miRNAs or miRs) represent a family of small non-coding RNAs (approximately 21–25 nt long) expressed in many organisms including animals, plants, and viruses [3]. MiRNAs are integral to gene regulation, apoptosis, hematopoietic development, and the maintenance of cell differentiation [3,4]. Researchers have identified abnormal expression of miRNAs in several types of malignancies including lung cancer [5–10]. MiRNAs have the capacity to target multiple biological functions essential to tumor progression. For example, miR-221 and -222 are upregulated in TNF-α related apoptosis-inducing ligand lung cancer cell lines. Silencing of these miRNAs sensitized resistant cell lines to TRAIL agents [11]. In human lung cancers, particularly small cell carcinoma, miR-17~92 is also over-expressed and in vitro introduction enhanced cell proliferation [12]. Selective silencing of both miR-17-5p and miR-20a induced apoptosis selectively in lung cancer cells over-expressing miR-17~92 [13].

MiR-133A and B are currently regarded as muscle specific miRNAs [14]. MiR-133A shares a transcriptional unit with miR-1 [15]. Through targeting of critical genes involved in cardiac development (Rho-A, Ccd42) and genes involved in cardiac channel expression (HCN2 and HCN4), miR1/133A/133B are implicated in the regulation of cardiac myogenesis and development and cardiac ion channel expression [16,17]. In addition, both miR-1 and 133 appear to alter cardiomyocyte apoptosis through targeting of HSP60 and 70 [14]. Few if any studies have investigated a potential role for these miRNA in non-cardiac disease. Recently, Nasser et al, demonstrated that miR-1 was decreased in lung cancer and that over-expression of miR-1 both in vitro and in vivo resulted in reduced tumor growth, migration and increased sensitivity to doxorubicin [18]. Herein, we demonstrate that miR-133B expression is reduced in human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In addition, miR-133B functionally targets the pro-survival molecules (myeloid cell leukemia 1) MCL-1 and B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 like 2 (BCL2L2 or BCL-W) and induces apoptosis NSCLC in the setting of chemotherapeutic agents.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Reagents

H23, H2172, H522, H2009, A549 (adenocarcinoma), H226, H1703 (squamous cell) (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) and primary normal human bronchial epithelial cells (NHBE) (ScienCell, Research Laboratories, Carlsbad, California) were maintained in 37°C humidified CO2 incubator and grown in appropriate media. Gemcitabine (25 nM) was used for drug treatment experiments (Eli Lilley, Indianapolis,IN)

Western Blotting

Cell and tissue lysates were prepared using RIPA Buffer with protease inhibitors and quantified using the BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, Illinois). 40 µg protein was loaded onto a 10% SDS-Page gel then transferred onto nitrocellulose and incubated with antibody (MCL-1 (NM_021960), BCL2L2 (NM_004050) (1:500, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Cleaved parp was measured by western blotting (Cell Signaling, 1:500, 89kDa). Blots were incubated at 4°C overnight in blocker (1% non-fat dry milk in TBS-Tween), followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary anti mouse or rabbit (ABR, Golden, Colorado). Blots were then developed using ECL Substrate (Pierce) following manufacturer’s instructions. Protein was normalized with β-actin (Sigma St. Louis, Missouri) and measured by densitometry by two independent researchers.

Quantitative-Reverse Transcriptase (q-RT) PCR Profiling

Lung tumors (adenocarcinoma) and non-involved adjacent lung were obtained through the Cooperative Human Tissue Network (The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board approved protocol) and stored at −80°C. Tissue was pulverized under liquid nitrogen and RNA extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Ca). RNA preps were analyzed for concentration and presence of degradation using a Nanodrop and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. The expression of 500 mature human miRNAs was profiled by real-time PCR to discover miRNAs that were differentially expressed in lung tissue from our cohort of patients. RNA (50 ng) was converted to cDNA by priming with a mixture of looped primers to 500 known human mature miRNAs in duplicate (Mega Plex kit, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). Primers to the internal controls snoRNAs U38B and U43 as well as 18S and 7S rRNA were included in the mix of primers. The expression was profiled using an Applied Biosystems 7900HT real-time PCR instrument equipped with a 384 well reaction plate. Liquid-handling robots and the Zymak Twister robot were used to increase throughput and reduce error. Real-time PCR was performed using standard conditions. Low expression miRNAs were filtered out if at least 80% samples have raw Ct score greater than 35. Median normalization method was also used to reduce technical bias of the experiment. A linear mixed model was fitted for each miRNA expression data by taking account of correlations within subjects. Statistical tests for differential expression were then conducted between tumor and normal samples. P-values were obtained and the significance level was determined by controlling the mean number of false positives using a false discovery rate of 1/198 or .005. Heat-maps of the expression values with hierarchical clustering were generated to aid in visualization. Data were presented as fold differences based on calculations of 2 (−ΔΔCt)

RT-PCR

TaqMan Reverse Transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California) Kit following manufacturer’s protocol and assayed on the Applied Biosystems 7900HT. The primer for miR-133B (UUUGGUCCCCUUCAACCAGCUA) was obtained from Applied Biosystems (Assay ID 002247). Data were presented as fold differences based on calculations of 2 (−ΔΔCt). Both U6 snRNA (Assay ID 001973) and RNU 43 (Assay ID 001095) (Applied Biosystems) were used as endogenous controls.

Cell Transfections

Cells were plated to 80% confluency and allowed to adhere overnight. Pre-miR-133B (5’ UCGUACCCG UGAGUAAU AAUGCG-3’) or a scrambled pre-miR control (Ambion, Austin, Texas) was reverse transfected (5–20 nM) using siPORT NeoFX transfection (Ambion, Austin,Texas) into cells in growth media following manufacturer’s recommendation. Following 48 hours, cells from either transfection protocol were harvested for protein analysis and for RNA extraction to confirm miRNA induction.

Luciferase Assays

The 3’UTRs (untranslated regions) of both BCL2L2 (1345bp) and MCL-1(844bp) were amplified by RT-PCR out of genomic DNA. The amplified products were sub-cloned into pENTR TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Ca.), and ligated into the Xho site of psi-CHECK-2 vector (Promega, Madison, WI). Proper insertion was confirmed by sequencing. In addition, we conducted mutagenesis of the 3’UTR (QuikChange XL, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and confirmed by sequencing. Cells were transfected with 50 ng of psiCHECK-MCL-1 or -BCL2L2 or psiCHECK empty vector and either 20 nM of scrambled pre-miR or pre-miR-133B. 48 hours following transfection, cells were assayed for both firefly and renilla luciferase using the dual luciferase glow assay (Promega, Madison, WI) and BioTek synergy HT fluorescent plate reader (Winooski, VT).

Target Prediction Analysis

Given the limitations of any single prediction program, we used two separate prediction programs (Targetscan 5.1 and PicTar) to identify common predicted targets for miR-133B. Target Scan 5.1 utilizes matching in the 3´ UTR for only 7mer and 8mer interactions sites.

In Situ Hybridization

Tissue was deparaffinized, protease treated (30 minutes in 2 mg/ml of pepsin in RNase free water), washed in sterile water, then 100% ethanol, and air-dried. LNA modified cDNA probe complementary to human mature miR-133B (TAGCTGGTTGAAGGGGACCAAA) was used (Exiqon Inc, Woburn, MA). The probes were labeled with the 3’ oligonucleotide tailing kit using biotin as the reporter nucleotide (Enzo Diagnostics, Farmingdale, NY). The probe-target complex was seen due to the action of alkaline phosphatase (as part of the streptavidin complex) on the chromogen nitroblue tetrazolium and bromochloroindolyl phosphate (NBT/BCIP) (Enzo Diagnostics). Nuclear fast red served as the counter stain. The negative controls were the omission of the probe and the use of a scrambled probe.

Apoptosis Assay

Cells were transfected with either pre-miR-133B/scrambled pre miR or MCL-1/BCL2L2 siRNA for 48 hours followed by 24 hour exposure to gemcitabine (25 nM) (Eli Lilley, Indianapolis,IN). Cells were analyzed for both annexin and PI by flow cytometry per protocol. (FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit, BD Pharmingen, San Diego,CA)

Statistical Analysis

Values were expressed as mean± S.E.M. Differences between two groups for statistical significance were conducted using a student’s t-test. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software, (San Diego California USA), www.graphpad.com. p<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

Differential expression of miR-133B in human NSCLC

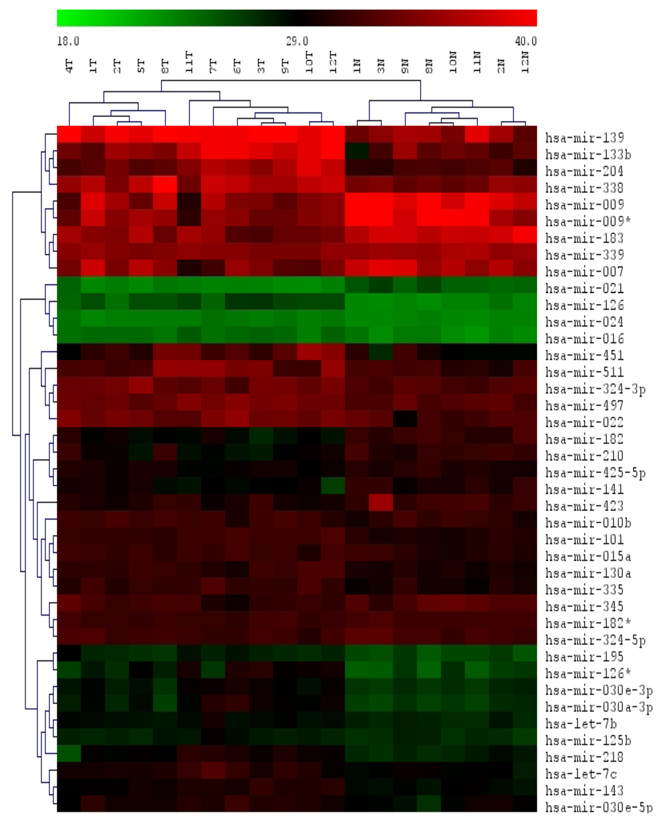

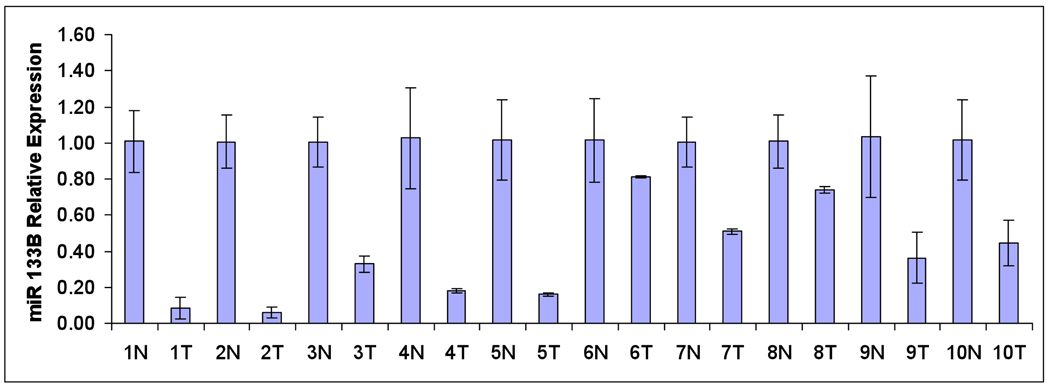

In this study, we examined differentially expressed miRNAs in a cohort of 8 cases of matched adenocarcinomas and adjacent uninvolved lung tissue and 4 additional non-paired adenocarcinomas. We used a high throughput qRT-PCR assay [19]. P-values were obtained and the significance level was determined by controlling the mean number of false positives [20,21]. Heat-maps of the expression values with hierarchical clustering were generated to aid in visualization. Out of 198 detected miRNA, we identified 41 differentially expressed miRNA using a false discovery rate of 1/198 or .005. Among these miRNA, 27 were upregulated and 14 downregulated (Figure 1A). Over-expressed miRNA included miR-183, 7, and 21 down-regulated miRNA included miR 126*, 126, let-7, and 101 have all been implicated in tumorigenesis [22]. Of note, miR-133B was the lowest expressed miRNA in adenocarcinomas compared to adjacent uninvolved lung tissue (28.62 fold down-regulated p=2.33E-05) (Figure 1B). We conducted qRT-PCR specifically for miR-133B in a separate cohort of paired cases of adenocarcinoma. In 10 cases, miR-133B was consistently reduced within tumor compared to uninvolved adjacent lung tissue (Figure 2C). In situ hybridization demonstrated that like miR-1, miR-133B localized to the bronchial epithelium [18] (Figure 2B).

Figure 1. MiRNA expression in human lung cancer.

(A) Heat map representing significantly altered miRNAs between 8 cases of paired adenocarcinomas (T) and uninvolved adjacent lung (N) and 4 non-paired adenocarcinoma cases. (B) Downregulated and upregulated miRNAs with fold changes and p values. Out of 198 detected miRNA, 41 miRNA were differentially expressed between tumor and adjacent lung using a false discovery rate of 1/198 or .005. Among these miRNA, 27 were upregulated and 14 downregulated. Of note, miR-133B was the lowest expressed miRNA in adenocarcinomas compared to adjacent uninvolved lung tissue (28.62 fold downregulated p=2.33E-05)

Figure 2. Relationship between miR-133B and MCL-1/BCL2L2.

(A) Location of predicted 3’UTR target sites for miR-133B in both MCL1 and BCL2L2 based on TargetScan 5.1 and PicTar prediction programs. (B) Representation of in situ expression of miR-133B in human lung tissue. Adenocarcinoma demonstrated no expression while in normal lung, miR-133B localizes to bronchial epithelium (arrow head), as a negative control no expression was evident of mock miRNA in normal lung. (C) qRT-PCR miRNA analysis in 10 additional cases of adenocarcinoma and adjacent uninvolved lung demonstrates reduced miR-133B expression in tumor tissue ((N)=Normal (T)=Tumor). Data was presented as fold differences based on calculations of 2 (−ΔΔCt) . With the exception of case 6, all demonstrated statistically significant differences with p<.05 (*) (D) Representation of MCL1 and BCL2L2 protein expression in 8 paired cases of adenocarcinoma (T) adjacent uninvolved lung (N). Protein was normalized with β-actin (Sigma St. Louis, Missouri) and measured by densitometry by two independent researchers.

Identifying Functional Targets of miR-133B

Base-pairing between the 3´ untranslated region (UTR) of the mRNA and the “seed sequence” located in the 5´ end of miRNA are essential to determining whether targeting miRNA results in degradation of mRNA or inhibition of translation [23]. Given that a miRNA can target a single gene up to hundreds of genes, in silico prediction algorithms exist for target prediction. Given the limitations of any single prediction program, we used two separate prediction programs (Targetscan 5.1 and PicTar) to identify common predicted targets for miR-133B [23–25]. Both programs identified BCL2L2 (BCL-W) and MCL-1 (myeloid cell leukemia 1) as predicted targets for miR-133B (Figure 2A). Both MCL-1 and BCL2L2 (BCL-W) are members of the B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family of apoptotic molecules [26]. Some BCL-2 family members share homology with BCL-2 and thus have anti-apoptotic properties while others with less homology have pro-apoptotic properties [26]. MCL-1and BCL2L2 are increased in a variety of both solid and hematological malignancies including lung cancer making them potential therapeutic targets [27,28]. Selective silencing of MCL1 and BCL2L2 induces spontaneous apoptosis in lung cancer cell lines and sensitize these cells to cytotoxic agents and radiation [27]. However, lung cancers may vary in their dependence on BCL-2 family members for apoptotic resistance and that the balance in BCL-2 proteins likely contributes to sensitivity [29].

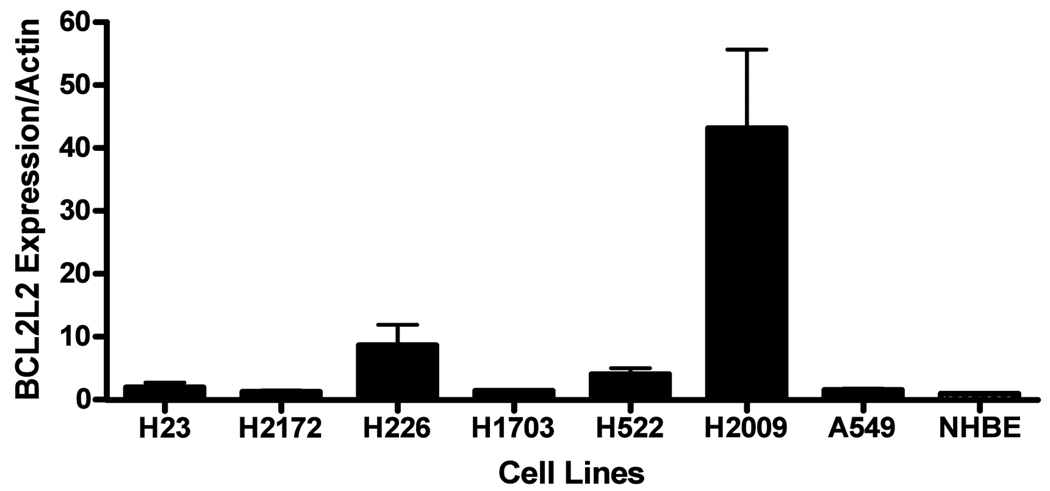

Both MCL-1and BCL2L2 were increased in tumors in five of eight cases. (Figure 2D) These findings are consistent with previous observations that tumors vary in dependence on patterns of expression of BCL-2 family members [26]. Because a multitude of factors including other miRNA may regulate a given protein we did not anticipate a strict inverse relationship between a single miRNA and a single target protein. However, screening of seven NSCLC cell lines did demonstrate that cell lines highly expressing miR-133B had lower levels of both MCL-1 and BCL2L2 protein (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. MiR-133B targets BCL2L2 and MCL1.

(a) Lung cancer cell line screening. NSCLC cell lines demonstrated an inverse relationship between MCL1/BCL2L2 and miR-133B expression. (b) Effects of miR-133B on MCL-1 and BCL2L2 mRNA and protein. Transient transfection of pre-miR-133B (5–20 nM) resulted in increasing expression of mature miR-133B as measured by q-RT-PCR. (*p<.05). Transfection of pre-miR-133B in H2009 NSCLC cell lines resulted in reduced MCL1 and BCL2L2 protein expression at 48 hours. (p<.05) However, neither MCL-1 nor BCL2L2 mRNA were altered. Protein was assessed and scored by densitometry by two independent researchers and westerns conducted in triplicate. MRNA was normalized to GAPDH. (c) MiR-133B targets 3’UTRs of both MCL-1 and BCL2L2. Cells were transfected with 50 ng of psiCHECK-MCL-1 (WT=wild type or Mut=mutant) or -BCL2L2 (WT=wild type. Mut=mutant) and either 20 nM of scrambled pre-miR or pre-miR-133B. 48 hours following transfection, cells were assayed for both firefly and renilla luciferase using the dual luciferase glow assay . All transfection experiments were conducted in triplicate. * p value< .05.

We next examined the effects of over-expression of miR-133B on target mRNA and protein expression. We first conducted transfection of several concentrations of pre-miR-133B (analogues that mimic precursor-miR-133B) and mock precursor (scrambled pre-miR with no target) in a NSCLC cell line (H2009) to confirm dose dependent effects on mature miR-133B expression (Figure 3B). As demonstrated in Figure 3B, transfection of pre-miR-133B compared to scrambled pre-miR reduced both MCL-1 and BCL2L2 protein at 48 hours post transfection following despite not changing MCL-1 and BCL2L2 mRNA (Figure 3B).

As confirmation of direct targeting of MCL-1 and BCL2L2, we cloned the 3’UTRs for both MCL-1 (844bp) and BCL2L2 (1345bp) into Renilla/Luciferase vectors and transfected H2009 cells with vector and either pre-miR-133B or scrambled pre-miR. Over-expression of miR-133B reduced expression of both reporter activities by 40% (Figure 3C). To validate binding specificity, we generated mutant constructs within the seed sequences for both 3’UTRs. Mutations in the MCL-1 3’UTR (GA to AG) and BCL2L2 3’UTR (GGA to TTG) eliminated the effect of miR-133B over-expression on reporter activity (Figure 3C). Of note, in silico prediction analysis identified several other miRNA that target MCL-1 and BCL2L2 (Supplemental Table 1). However, we identified only seven miRNA including miR-133 A/B that were predicted to target both. Potential combinatorial effects of other miRNA on target mRNA regulation may explain why we observed only partial reduction in vector activity.

miR-133B and Apoptosis

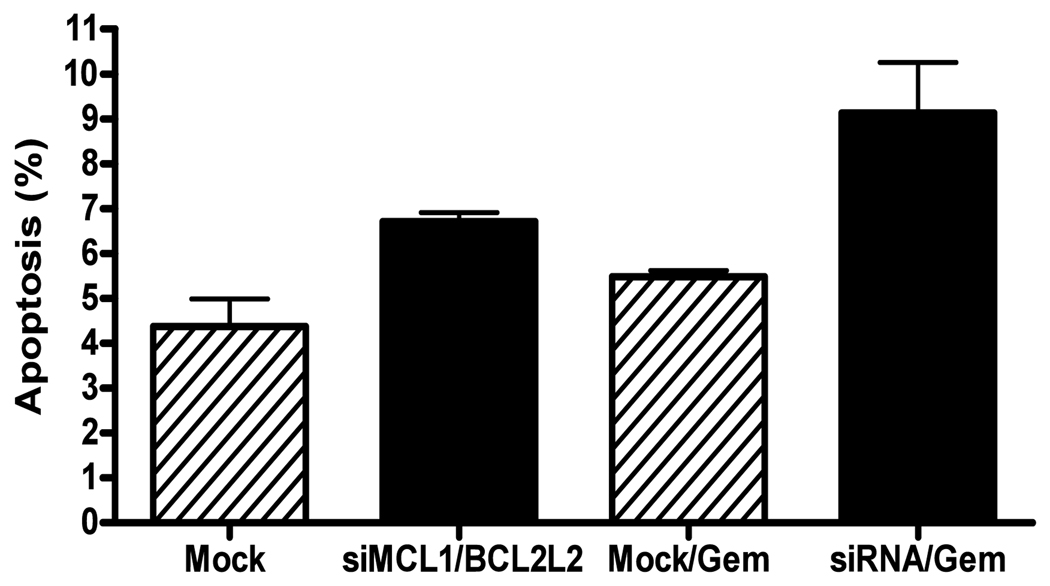

Used in several solid malignancies, gemcitabine is a chemotherapeutic agent utilized in combination with platinum based therapy as first line therapy in advanced NSCLC [30]. In addition, gemcitabine can induce apoptosis in a BCL-2 family member dependent manner [31,32]. We assessed for the induction of apoptosis through the measurement of cleaved parp by western blot analysis and flow cytometry for annexin/PI. MiR-133B over-expression resulted in a small degree of apoptosis (Figure 4B). MiR-133B over-expression in combination with 24 hours of gemcitabine treatment resulted in increased cleaved parp expression as well as apoptosis compared to mock treated cells (17% vs. 7%) (Figure 4 A,B). We next selectively silenced MCL-1 and BCL2L2 (Figure 4A). Silencing of both MCL-1 and BCL2L2 resulted in the induction of cleaved parp. However, in the setting of gemcitabine exposure, silencing of MCL-1 and BCL2L2 induced higher apoptosis than mock transfected cells (Figure 4B). The degree of apoptosis was not as high as that seen in miR-133B treated cells. These findings may suggest that impact of miR-133B on cell survival is likely mediated by targets beyond MCL-1 and BCL2L2. Lastly, pre-miR-133B/gemcitabine treated cells had reduced MCL-1 and BCL2L2 protein expression compared to mock pre-miR/gemcitabine or gemcitabine alone treated cells (Figure 4C). The effects on BCL2L2 were more pronounced.

Figure 4. Effects of miR-133B on Apoptosis.

(A) Silencing of MCL-1 and BCL2L2. MiR-133B induction and MCL-1 and BCL2L2 siRNA both resulted in an increase in cleaved parp in NSCLC cells lines. (B) MiR-133B over-expression and MCL-1/BCL2L2 siRNA increased gemcitabine induced apoptosis. Cells were transfected with either pre-miR-133B/mock pre miR or MCL-1/BCL2L2 siRNA for 48 hours followed by 24 hour exposure to gemcitabine (25 nM). Both annexin and annexin/PI staining cells were included in our analysis. Flow cytometry was conducted in duplicate on two separate days. (C) Effects of miR-133B and gemcitabine on MCL-1 and BCL2L2 Expression. Transfection of H2009 cell line with pre-miR-133B followed by treatment with gemcitabine (25nM) decreased both MCL-1 and BCL2L2 protein .Westerns for MCL-1 and BCL2L2 and densitometry were conducted as previously described. *p<.05

Tumor progression is reliant on several factors including the production of self-sufficient growth signals, establishment of independent blood supply and resistance to apoptotic stimuli [33]. In 2005, Cimmino et al. first determined that both miR-15 and -16 were reduced in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) and that these miRNA could induce apoptosis in a leukemic cell line through direct targeting of BCL-2 [34]. MiR 15/16 and BCL-2 may be of biological relevance in other malignancies including gastric carcinoma [35]. Recently, investigators determined that miR-29 could directly target MCL-1 in a cholangiocarcinoma [36]. Localized to chromosome 6, miR-133B has been previously described to have muscle specific expression [17]. Studies have demonstrated reduced expression of miR-133B in colorectal carcinoma [37]. Investigators determined that miR-133B harbored anti-tumorigenic properties in tongue squamous cell carcinoma through direct targeting of pyruvate kinase type M2 [38]. In our study, over-expression of miR-133B increased apoptosis in response to gemcitabine and reduced MCL-1 and BCL2L2 expression. To our knowledge, this represents the first observation of reduced miR-133B expression in human lung cancers and effects on cancer cell survival. Further studies that seek to validate other targets of miR-133B as well as mechanisms for suppression will be important to identifying its potential as a therapeutic agent in lung cancer.

Supplementary Material

miRNA in red target both BCL2L2 and MCL-1.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants #HL077717 (S.P.N.) and Chest/LUNGevity Foundation Grant (S.P.N.).

The authors would like to thank Drs. Carlo Croce and Melissa Piper for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2009 doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Bichi R, Zupo S, Noch E, Aldler H, Rattan S, Keating M, Rai K, Rassenti L, Kipps T, Negrini M, Bullrich F, Croce CM. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Leva G, Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNAs: Fundamental facts and involvement in human diseases. Birth Defects Res. C. Embryo. Today. 2006;78:180–189. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krutzfeldt J, Stoffel M. MicroRNAs: a new class of regulatory genes affecting metabolism. Cell Metab. 2006;4:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calin GA, Liu CG, Sevignani C, Ferracin M, Felli N, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Cimmino A, Zupo S, Dono M, Dell'Aquila ML, Alder H, Rassenti L, Kipps TJ, Bullrich F, Negrini M, Croce CM. MicroRNA profiling reveals distinct signatures in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemias. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:11755–11760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404432101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang J, Lee EJ, Gusev Y, Schmittgen TD. Real-time expression profiling of microRNA precursors in human cancer cell lines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5394–5403. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki863. (2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schetter AJ, Leung SY, Sohn JJ, Zanetti KA, Bowman ED, Yanaihara N, Yuen ST, Chan TL, Kwong DL, Au GK, Liu CG, Calin GA, Croce CM, Harris CC. MicroRNA expression profiles associated with prognosis and therapeutic outcome in colon adenocarcinoma. JAMA. 2008;299:425–436. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.4.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yanaihara N, Caplen N, Bowman E, Seike M, Kumamoto K, Yi M, Stephens RM, Okamoto A, Yokota J, Tanaka T, Calin GA, Liu CG, Croce CM, Harris CC. Unique microRNA molecular profiles in lung cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calin GA, Croce CM. Chromosomal rearrangements and microRNAs: a new cancer link with clinical implications. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:2059–2066. doi: 10.1172/JCI32577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Liu CG, Veronese A, Spizzo R, Sabbioni S, Magri E, Pedriali M, Fabbri M, Campiglio M, Menard S, Palazzo JP, Rosenberg A, Musiani P, Volinia S, Nenci I, Calin GA, Querzoli P, Negrini M, Croce CM. MicroRNA gene expression deregulation in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7065–7070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garofalo M, Quintavalle C, Di Leva G, Zanca C, Romano G, Taccioli C, Liu CG, Croce CM, Condorelli G. MicroRNA signatures of TRAIL resistance in human non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:3845–3855. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashita Y, Osada H, Tatematsu Y, Yamada H, Yanagisawa K, Tomida S, Yatabe Y, Kawahara K, Sekido Y, Takahashi T. A polycistronic microRNA cluster, miR-17-92, is overexpressed in human lung cancers and enhances cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9628–9632. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsubara H, Takeuchi T, Nishikawa E, Yanagisawa K, Hayashita Y, Ebi H, Yamada H, Suzuki M, Nagino M, Nimura Y, Osada H, Takahashi T. Apoptosis induction by antisense oligonucleotides against miR-17-5p and miR-20a in lung cancers overexpressing miR-17-92. Oncogene. 2007;26:6099–6105. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu C, Lu Y, Pan Z, Chu W, Luo X, Lin H, Xiao J, Shan H, Wang Z, Yang B. The muscle-specific microRNAs miR-1 and miR-133 produce opposing effects on apoptosis by targeting HSP60, HSP70 and caspase-9 in cardiomyocytes. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:3045–3052. doi: 10.1242/jcs.010728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen JF, Mandel EM, Thomson JM, Wu Q, Callis TE, Hammond SM, Conlon FL, Wang DZ. The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:228–233. doi: 10.1038/ng1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo X, Lin H, Pan Z, Xiao J, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Yang B, Wang Z. Down-regulation of miR-1/miR-133 contributes to re-expression of pacemaker channel genes HCN2 and HCN4 in hypertrophic heart. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:20045–20052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801035200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Care A, Catalucci D, Felicetti F, Bonci D, Addario A, Gallo P, Bang ML, Segnalini P, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Elia L, Latronico MV, Hoydal M, Autore C, Russo MA, Dorn GW, Ellingsen O, Ruiz-Lozano P, Peterson KL, Croce CM, Peschle C, Condorelli G. MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat. Med. 2007;13:613–618. doi: 10.1038/nm1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nasser MW, Datta J, Nuovo G, Kutay H, Motiwala T, Majumder S, Wang B, Suster S, Jacob ST, Ghoshal K. Down-regulation of micro-RNA-1 (miR-1) in lung cancer. Suppression of tumorigenic property of lung cancer cells and their sensitization to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis by miR-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:33394–33405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804788200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19.Schmittgen TD, Lee EJ, Jiang J. High-throughput real-time PCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;429:89–98. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-040-3_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmittgen TD, Lee EJ, Jiang J, Sarkar A, Yang L, Elton TS, Chen C. Real-time PCR quantification of precursor and mature microRNA. Methods. 2008;44:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu X, Piper-Hunter MG, Crawford M, Nuovo GJ, Marsh CB, Otterson GA, Nana-Sinkam SP. MicroRNAs in the Pathogenesis of Lung Cancer. [a];J. Thorac. Oncol. 2009 doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a99c77. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing1. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomadaki H, Scorilas A. BCL2 family of apoptosis-related genes: functions and clinical implications in cancer. Crit Rev. Clin. Lab Sci. 2006;43:1–67. doi: 10.1080/10408360500295626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song L, Coppola D, Livingston S, Cress D, Haura EB. Mcl-1 regulates survival and sensitivity to diverse apoptotic stimuli in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2005;4:267–276. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.3.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawasaki T, Yokoi S, Tsuda H, Izumi H, Kozaki K, Aida S, Ozeki Y, Yoshizawa Y, Imoto I, Inazawa J. BCL2L2 is a probable target for novel 14q11.2 amplification detected in a non-small cell lung cancer cell line. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1070–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang TM, Barbone D, Fennell DA, Broaddus VC. Bcl-2 family proteins contribute to apoptotic resistance in lung cancer multicellular spheroids. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2009;41:14–23. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0320OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danesi R, Altavilla G, Giovannetti E, Rosell R. Pharmacogenomics of gemcitabine in non-small-cell lung cancer and other solid tumors. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:69–80. doi: 10.2217/14622416.10.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang GC, Hsu SL, Tsai JR, Wu WJ, Chen CY, Sheu GT. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation and Bcl-2 downregulation mediate apoptosis after gemcitabine treatment partly via a p53-independent pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004;502:169–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skoda C, Erovic BM, Wachek V, Vormittag L, Wrba F, Martinek H, Heiduschka G, Kloimstein P, Selzer E, Thurnher D. Down-regulation of Mcl-1 with antisense technology alters the effect of various cytotoxic agents used in treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Oncol. Rep. 2008;19:1499–1503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cimmino A, Calin GA, Fabbri M, Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Shimizu M, Wojcik SE, Aqeilan RI, Zupo S, Dono M, Rassenti L, Alder H, Volinia S, Liu CG, Kipps TJ, Negrini M, Croce CM. miR-15 and miR-16 induce apoptosis by targeting BCL2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:13944–13949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506654102. [34] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia L, Zhang D, Du R, Pan Y, Zhao L, Sun S, Hong L, Liu J, Fan D. miR-15b and miR-16 modulate multidrug resistance by targeting BCL2 in human gastric cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;123:372–379. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mott JL, Kobayashi S, Bronk SF, Gores GJ. mir-29 regulates Mcl-1 protein expression and apoptosis. Oncogene. 2007;26:6133–6140. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bandres E, Cubedo E, Agirre X, Malumbres R, Zarate R, Ramirez N, Abajo A, Navarro A, Moreno I, Monzo M, Garcia-Foncillas J. Identification by Real-time PCR of 13 mature microRNAs differentially expressed in colorectal cancer and non-tumoral tissues. Mol. Cancer. 2006;5:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong TS, Liu XB, Chung-Wai HA, Po-Wing YA, Wai-Man NR, Ignace WW. Identification of pyruvate kinase type M2 as potential oncoprotein in squamous cell carcinoma of tongue through microRNA profiling. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;123:251–257. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

miRNA in red target both BCL2L2 and MCL-1.