SYNOPSIS

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is a malignant, relentless brain cancer with no known cure, and standard therapies leave significant room for the development of better, more effective treatments. Immunotherapy is a promising approach to the treatment of solid tumors that directs the patient’s own immune system to destroy tumor cells. The most widespread and successful immunologically-based cancer therapy to date involves the passive administration of monoclonal antibodies, but significant antitumor responses have also been generated with active vaccination strategies and cell-transfer therapies as well. This article summarizes the important components of the immune system, discusses the specific difficulty of immunologic privilege in the central nervous system (CNS), and reviews the variety of treatment approaches that are being attempted, with an emphasis on active immunotherapy using peptide vaccines in the treatment of GBM.

Keywords: brain neoplasms, glioblastoma, immunotherapy, epidermal growth factor receptor, neoplasm antigens, immune system

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common primary malignant tumor in the adult central nervous system.[1] Current therapy for this disease usually includes surgical resection, radiation, and the administration of temozolomide chemotherapy. It is a devastating diagnosis, since even with this standard treatment, median survival is less than 15 months.[2] Additionally, most current therapies are not selective for tumor cells; and therefore, large amounts of normal healthy tissue are injured as collateral damage while treating these tumors. This is a problem for most types of cancer, and particularly GBM since it is highly infiltrative.

The ideal treatment for GBM needs to be selective enough to accurately discriminate between normal tissue and tumor cells and be able to reach across the blood brain barrier, while being potent enough to kill all of the tumor cells. The immune system certainly has this capability as evidenced by its ability to fight infections within the CNS. Therefore, the immune system could be an ideal candidate for an effective GBM therapy as well. Although it would appear that the immune system inherently possesses the ability to recognize and eliminate GBMs, the fact that GBMs are able to proliferate in these patients suggests that without intervention, the immune system is not an effective check against this disease. The reasons for this failure are likely multifactorial, including the immune-privileged status of the CNS and immunosuppressive effects of the tumor. As there is clearly a significant need for more effective treatment options against GBM, attempting to direct the immune system to attack this disease is a promising area of active research.

Immunotherapy

Multiple different approaches are being employed to activate the immune system against the tumor. In order to provoke the immune system into being stimulated against tumor cells, attempts have included injections of peptides, proteins, DNA, RNA, viruses encoding cancer antigens, virus-like particles, whole tumor cells or their lysates, altered tumor cells that express cytokines, heat shock proteins, pulsed dendritic cells (DCs), and anti-idiotype antibodies.[3, 4] Other methods are directed at overcoming tumor-related immune suppression by blocking the effect of inhibitory cells of the immune system or by blocking the effect of inhibitory molecules secreted by tumors like transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). Administration of cytokines that promote lymphocyte expansion have lead to some cases of dramatic tumor regression. For example interleukin-2 (IL-2) has been studied in the treatment of renal cancer, metastatic melanoma, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with some important treatment successes.[5–8]

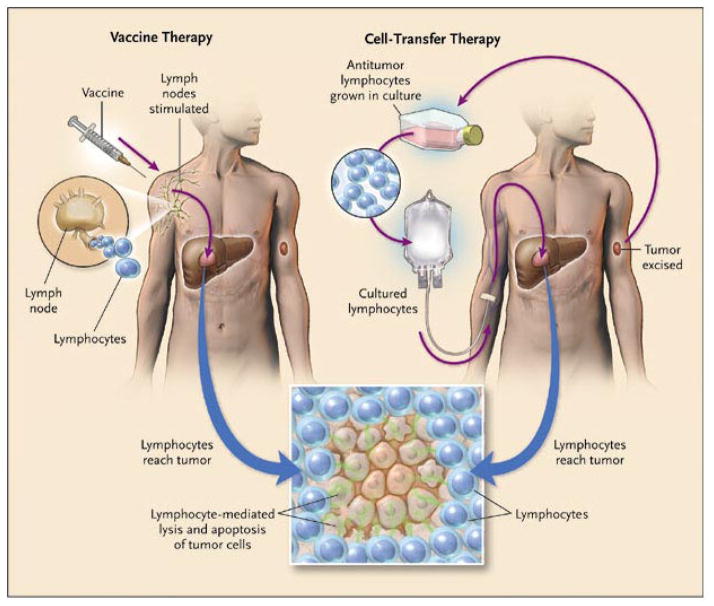

The two main approaches for immunotherapy can be grouped into (active) vaccine therapy or (passive or adoptive) cell-transfer therapy (Figure 1).[9] To be successful, both approaches require the patient to develop lymphocytes that are activated against tumor cell antigens. Vaccine therapy in general follows the principle that injections of various substances that ultimately result in the presentation of tumor peptides to the patient’s immune system will sensitize lymphocytes against an antigen of interest, and then these lymphocytes migrate to the tumor and cause cell killing. Vaccines typically are derived from cancer cells, cancer cell lysates, or specific peptides or proteins that encode cancer antigens. These can be pulsed onto antigen presenting cells (APCs) which are then injected, or can be administered by themselves with adjuvants or cytokines that stimulate the immune system in a non-specific manner.[10]

Figure 1. Schematic of the two main immunotherapy strategies.

Vaccine therapy attempts to generate an antitumor response by activating the immune system of the patient in vivo. Cell-Transfer Therapy removes lymphocytes from the patient, activates them in vitro against the tumor, then infuses them back into the patient. From Rosenberg SA. Shedding light on immunotherapy for cancer. N Engl J Med. Apr 1 2004;350(14):1462, with permission. Copyright © 2004 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

In contrast, cell-transfer therapy involves removing lymphocytes from the patient, expanding those lymphocytes, usually T cells, that demonstrate activity against the tumor antigens, and then reintroducing that expanded and enriched cell population back into the same patient so they can migrate to the tumor and cause cell killing. In one form of cell-transfer therapy, T cells that are able to respond to defined cancer antigens are harvested from resected tumors and are termed tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). Importantly, ex vivo cell transfer therapy allows one to directly manipulate both the lymphocytes outside of the body and the host immune system itself prior to infusion. It is thought that these manipulations prior to infusion are beneficial since they allow for stimulation and expansion of the cells at the time of reinfusion and also correction of the host environment to make it more hospitable for the infused, activated cells to be able to attack the tumor.[10] In fact, such host manipulations have recently enhanced the success of cell transfer therapy significantly and revolutionized this approach.

Immune System Components

The role of the immune system is basically to discriminate between self and non-self, and thereby defend the body from foreign attack. This role is critical for defense from microorganisms and other pathogens, but also prunes the body’s own cells, causing removal of those cells that are no longer viable or exhibit a number of different warning signals to the immune system. The immune system is traditionally divided into two main arms, the innate and adaptive systems. The innate system is composed of macrophages/monocytes, neutrophils, natural killer cells, basophils, and eosinophils. The complement system is also a component of the innate system. The innate system is so named because it is present from birth, and it provides the initial line of defense, but it is not as specific as the adaptive system and does not have any memory of the protein previously defended against.[11]

In contrast, the adaptive immune system is able to refine its response to improve its ability to detect and respond against a specific offender particularly if it has defended against this foreigner previously. The main components of the adaptive immune system are T and B lymphocytes, and both cell types are able to adapt their response to foreign antigens and microorganisms. T cells are named due to their maturation in the thymus. Mature T cells are mainly divided into CD8+ cytotoxic and CD4+ helper cell types. Both types possess a T cell receptor, and through this they bind to and recognize foreign antigens that are presented on the surface of tumor cells or cells infected by viruses. These antigens are small peptide fragments that are presented in the groove of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules that are present on almost all cells in the human body. CD8+ cells recognize HLA class I molecules, and the peptide antigen presented on these molecules are typically 8–10 amino acids in length. These peptides come from intracellular proteins that are broken down in the proteasome. When activated, CD8+ cells typically cause cell-mediated killing. CD4+ cells, in contrast, recognize HLA class II molecules, and these molecules present peptides that are typically 13 amino acids in length. These peptides that are presented on class II molecules arise from the digestion of extracellular proteins that were taken into the cell via endocytosis. After activation, CD4+ cells modulate the immune response by secreting different cytokines, and in general adjust the response of other cells of the immune system.[11] Most cells in the body express HLA class I molecules, but HLA class II expression is limited to antigen presenting cells.

B cells are named because of their derivation from precursor cells in the bone marrow. They are a component of the adaptive response, and they secrete antibodies in response to foreign antigens. Antibodies are secreted in 5 main types: IgG, IgM, IgE, IgD, and IgA.[12] Antibodies bind to specific antigens through protein-protein non-covalent biding, and this can lead to destruction of the offending cell or microorganism through a variety of means. In theory at least, each antibody recognizes a single antigen, but the wide diversity of antibodies that is created allows them as a whole to recognize a large number of antigens. When cells become abnormal from infection, mutation, or other danger to the host, they can change their surface protein expression. These altered or unique proteins can become antigens that can then be bound by antibodies, which leads to immune detection and subsequent killing of these cells by natural killer cells. This is called antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC).

CNS Immune Privilege

It was classically believed that a few areas of the body, including the CNS, are privileged from standard surveillance by the immune system. Early studies by Medawar et al. in 1948 suggested that tissue grafts transplanted into the brain and other sites were not rejected, suggesting that these areas were not under immune surveillance.[13] This idea has been supported by numerous findings specific to the CNS, including the decreased amount of HLA antigen presentation, the lack of conventional antigen presenting cells, the lack of a conventional lymphatic drainage system, and the existence of the blood brain barrier (BBB), which helps to block entry into the CNS. However, the reality is much more complicated and cells of the immune system are able to enter and interact with the CNS to a great extent. Furthermore, HLA antigen presentation does occur on astrocytes, microglia, endothelial cells, and in the choroid plexus, and microglia in particular may be the predominant antigen presenting cells within the CNS.[12, 14, 15] Although traditional lymphatics are not present in the CNS, it has been suggested that cervical lymph nodes do receive lymphatic drainage from the brain and that an immune response can be generated against antigens in the brain via this pathway.[16]

Antibody penetration across the BBB has generally been thought to be poor, since there is a low level of immunoglobulin in the CNS as compared to serum levels. Importantly, antibody permeability can drastically increase in certain conditions such as widespread inflammation. Furthermore, antibodies have been shown to penetrate the CNS, although at 0.1–10% of the peripheral blood levels.[14]

Early results from our group proved in humans that a radiolabeled monoclonal antibody against the extracellular matrix antigen tenascin was able to reach intracerebral tumor when given via intravenous administration, although only 0.0006–0.0043% of the total injected dose was measured at the tumor site.[17] Despite the low dose, this demonstrates that antibody is able to reach intracerebral tumors. However, it also suggests that in order to achieve clinical benefits, it may be necessary to give higher or more sustained doses of antibody, or more specific antibodies that do not exhibit systemic binding.

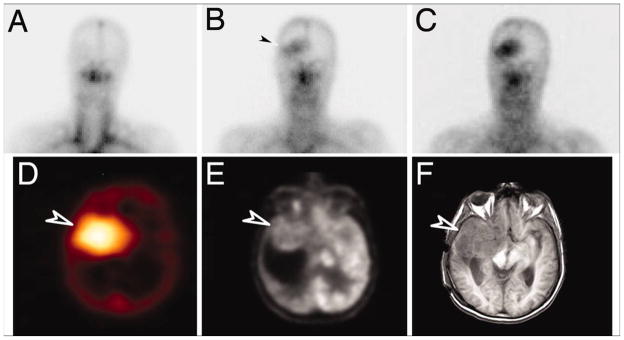

Later studies using antibodies recognizing epitopes restricted to the CNS have confirmed that antibodies can localize to the site of an intracerebral glioma after systemic administration, as Figure 2 depicts.[18] In this study, monoclonal antibody 806 was used, which recognizes the tumor-specific antigen, EGFRvIII. This antibody was radiolabeled with Indium-111, and after a single dose was administered, imaging verified that the radiolabeled antibody localized to the intracerebral tumor site with no evidence of uptake in normal tissues. Localization of antibody to subcutaneous tumor xenografts in mice has also been published.[19] When an antibody is highly specific for the tumor and does not cross-react with systemic antigens, the lack of systemic binding may make it possible to get a much higher percentage of antibody penetration into the CNS and to the tumor site.

Figure 2. Localization of a radiolabeled, tumor-specific monoclonal antibody against a CNS glioma.

A monoclonal antibody, ch806, which recognizes a tumor-specific mutation in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFRvIII) was radiolabeled with Indium-111 and infused into a patient with an anaplastic astrocytoma. A–C all depict gamma camera images of the head, with A representing day 0 of infusion, B representing day 3, and C representing day 7 after infusion. Over time, increased radioactivity at the right temporal tumor site can be seen. Black arrowhead in B illustrates the first visualization of radiolabeled antibody at the tumor site. D is SPECT imaging that demonstrates antibody uptake at the right temporal tumor site. E demonstrates tumor localization with FDG-PET, and F is an axial MRI slice at the equivalent level that demonstrates that the right temporal tumor is in the same location as the antibody uptake. White arrowheads in D–F point to the tumor region. From Scott AM, Lee FT, Tebbutt N, et al. A phase I clinical trial with monoclonal antibody ch806 targeting transitional state and mutant epidermal growth factor receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Mar 6 2007;104(10):4073, with permission. Copyright 2007 National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A.

Moreover, the existence of paraneoplastic syndromes conclusively demonstrates that antibodies can penetrate the CNS at clinically significant levels. In this spectrum of disorders, antibodies directed against systemic tumor antigens have cross-reactivity with neuronal cells and therefore provoke an immune response in the CNS that leads to significant clinical morbidity.[20] Numerous antibodies arising from a variety of different cancers have been detected, including anti-Hu, anti-Yo, anti-Ri, anti-CV2, anti-Ma, anti-Tr, anti-amphiphysin, VGKC antibodies, anti-VGCC antibodies, and antibodies to the NMDA receptor.[21–23] Many of these antibodies can also be detected in the CSF of affected individuals. Along with antibodies, T cell responses in the CNS are also seen and it is thought that both responses contribute to the neuronal injury seen in these diseases.[22, 24] Often, in addition to treatment of the underlying tumor, immune suppression is used to control the CNS immune response.[25–28]

While it appears that antibody responses may be a more predominant aspect of the response against CNS antigens than cell mediated responses, all aspects of the immune response are able to be generated in the CNS.[14] Prior experiments have shown that activated T cells can readily cross an intact BBB.[29] When these activated T cells are specific to myelin basic protein, they can cause normal rats to undergo lethal experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE).[30] Numerous adhesion molecules and chemotactic factors have been implicated in this process. Naïve T cells are not believed to cross the normal BBB, however.

As an acknowledgement to the limitations caused by the BBB, there have also been attempts to bypass it via direct drug delivery to the brain. Some of the more promising of these methods include transnasal drug delivery and convection-enhanced delivery (CED). Transnasal drug delivery can theoretically bypass the blood brain barrier and achieve drug levels in the CNS, although this method has largely failed when it has been studied in humans.[31, 32] Another important method that may be successful in the future is convection-enhanced delivery (CED), where drug is delivered via catheters directly to the tumor site under a steady pressure.[33] This method permits better drug distribution than simple diffusion, and should distribute drug over much greater areas in a more homogenous fashion.[34] This method has been successfully utilized by our group and others in humans for targeted treatment of GBM.[35–37] Research is ongoing in all of these areas, and much more work still needs to be done to validate these various delivery techniques.

Tumor-Related Immune Suppression

Tumors appear to be accompanied by immune suppression both locally and systemically. This is likely multifactorial in nature, and multiple immunosuppressive molecules have been implicated in addition to the important role suggested by inhibitory cells of the immune system. For example, TGF-β, a cytokine secreted by many tumor cells appears to be an important component of this immunosuppression.[38] Fas ligand, a protein on the surface of many tumor cells that is capable of killing T cells directly, may also be important in inhibiting the immune response.[39] Many other molecules have also been implicated and may play important roles, including IL-10, prostaglandin E2, and NF-κB.[40, 41] Regulatory T cells are a subset of CD4+ cells and generally function as inhibitory cells of the immune system.[14, 42–44] They have been shown to be an increased fraction of lymphocyte counts in patients with GBMs, [45] and their depletion has been shown to improve antitumor responses.[41] Also, the inhibitory T cell receptor CTLA-4 is likely involved, since it has been shown that blockade of this receptor improves anti-tumor immune response.[46] Tumors are also known to have immune evasion techniques, including decreased amount of antigen presentation molecules.[41] It will undoubtedly be critical to understand and overcome the immune suppression and evasion techniques in order to develop an effective immunotherapy.

Monoclonal Antibodies as Therapeutics

There have been numerous clinical trials verifying the passive administration of monoclonal antibodies as a viable treatment for cancer. Antibodies have been approved for the treatment of breast cancers, lung cancers, colorectal cancers, and leukemias and lymphomas. Food and Drug Administration approval has been granted for trastuzumab (Herceptin), bevacizumab (Avastin), cetuximab (Erbitux), panitumumab (ABX-EGF), ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin), alemtuzumab (Campath), gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg), rituximab (Rituxan), and tositumomab (Bexxar).[40] Trastuzumab is a monoclonal antibody against the HER2 receptor and is approved for HER2-positive breast cancer. Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor and is approved for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and very recently recurrent GBM. Cetuximab and panitumumab are both directed against the epidermal growth factor receptor, and both are approved for colorectal cancer while cetuximab also has approval against head and neck cancer. The remainder of the listed antibodies are directed against cell surface antigens and are approved for the treatment of leukemias and lymphomas.

Bevacizumab has also demonstrated efficacy against metastatic renal cancer[47] and in combination with irinotecan, it has shown efficacy against recurrent GBM.[48] The mechanism of this synergistic effect may be due to slowing tumor growth by slowing angiogenesis, or it possibly may allow for improved delivery of chemotherapy to the tumor by normalizing tumor vasculature. Further studies with bevacizumab against GBM are ongoing, and it recently obtained approval for treatment of recurrent GBM. Interestingly, bevacizumab has also demonstrated efficacy against pituitary adenomas in a mouse model, [49] and newer antibodies that block vascular endothelial growth factor in both humans and mice have also been developed.[50]

Trastuzumab has become an important component of HER2-positive breast cancer therapy, [51] and due to the high prevalence of metastases to the CNS in this disease, there have been a number of studies with data related to the CNS. It has been shown that patients with HER2-overexpressing breast cancer have a greater risk of developing CNS metastases than other breast cancer patients.[52, 53] There is also an increased incidence of CNS metastases in those HER2-positive patients who are undergoing treatment with trastuzumab, but due to the improved control of extracranial disease, there is still improved survival of these patients when compared to unselected breast cancer patients.[53–56] Another study showed that despite a survival benefit from trastuzumab therapy, there was no delay in onset of CNS metastases, which suggests that this drug is having little effect across the blood brain barrier.[57] The possibility that the brain metastases lost their HER2 expression (and would therefore be resistant to the drug) was ruled out in other studies, [58] which supports the conclusion that the drug is simply not being effectively delivered to CNS disease. Furthermore, the ratio of trastuzumab between serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has been measured during different stages of treatment and disease burdens. Before radiotherapy, the ratio of serum to CSF was 420:1, but this improves to 76:1 after radiotherapy, and after radiotherapy with meningeal carcinomatosis this ratio is 49:1.[59] Other authors have reported in a patient with meningeal carcinomatosis that this ratio was 300:1, [60] but others have also reported on possible treatment benefits of trastuzumab for meningeal carcinomatosis despite these ratios.[61] In summary, it appears that large monoclonal antibodies like trastuzumab are able to penetrate the CNS, but at much lower levels than that found in the serum. In the case of breast cancer, it is important to emphasize that radiation weakens the blood brain barrier and improves serum to CSF ratios of trastuzumab. Since radiation has become part of the standard therapy for GBM, its effect may decrease the role of the blood brain barrier for that disease as well.

Tumor-associated and Tumor-specific antigens

One way to direct the immune system against tumors is to target it against individual antigens that are expressed by tumor cells. A possible concern with this approach is that by focusing the immune attack towards one antigen, there may be tumor cells that escape immune destruction if those cells lack or downregulate that specific antigen. The strength of this concern depends on the importance of that specific antigen for tumorigenesis. In general, tumor antigens can be described as being either tumor-associated or tumor-specific antigens. Tumor-associated antigens are normal antigens found throughout the body but are overexpressed in tumor cells. Tumor-specific antigens are novel antigens found only on tumor cells. These specific antigens arise from gene mutations or splice variations.

Other important antigens include viral antigens that are expressed when a virus is implicated in the tumor. Examples of these antigens are the products of human papillomavirus in cervical cancer specimens, [62] antigens from Epstein-Barr virus in Burkitt’s lymphoma or nasopharyngeal carcinoma specimens, [63] and possibly even antigens from Cytomegalovirus in GBM.[64]

Tumor-associated antigens comprise the majority of tumor antigens targeted by immunotherapy strategies to date, and have been described in a variety of different cancers. They can be classified based on how they are presented by HLA molecules.[10] Class I-restricted tumor antigens are presented to CD8+ T-cells, and include melanoma-melanocyte differentiation antigens such as gp100, [65] MART-1, [66] and tyrosinase, [67] cancer-testes antigens such as MAGE [68–71] and NY-ESO-1 [72, 73], and also MUC-1 [74] and HER2/Neu.[75] Class II-restricted tumor-associated antigens, which can overlap with some Class I-restricted antigens, are recognized by CD4+ T-cells and include non-mutated protein epitopes such as gp100, [76] MAGE-3, [77] and NY-ESO-1.[78]

While tumor-associated antigens can be used as targets for immunotherapy, it may be more difficult to provoke an immune response against a normally-expressed antigen due to preexisting immunologic tolerance to that antigen. So as to limit immune responses against or normal tissues, immune responses against normal proteins are generally turned off. Furthermore, any response that is generated could also have increased toxicity by the response being unintentionally directed against normal tissues. Because normal cells also express the same antigens, there may be an increased risk of autoimmune attack on normal tissue.[79, 80]

Tumor-specific antigens are not expressed on normal cells and are therefore ideal targets for vaccines. The lack of expression of these antigens on normal cells allows for a focused immune response. Since this response should not be diluted by systemic antigen expression, it may be possible to achieve a stronger response across the blood brain barrier and it is hoped that systemic toxicity will be more limited. Unfortunately, many tumor-specific antigens are inconsistent and patient-specific, making them difficult to characterize and target.

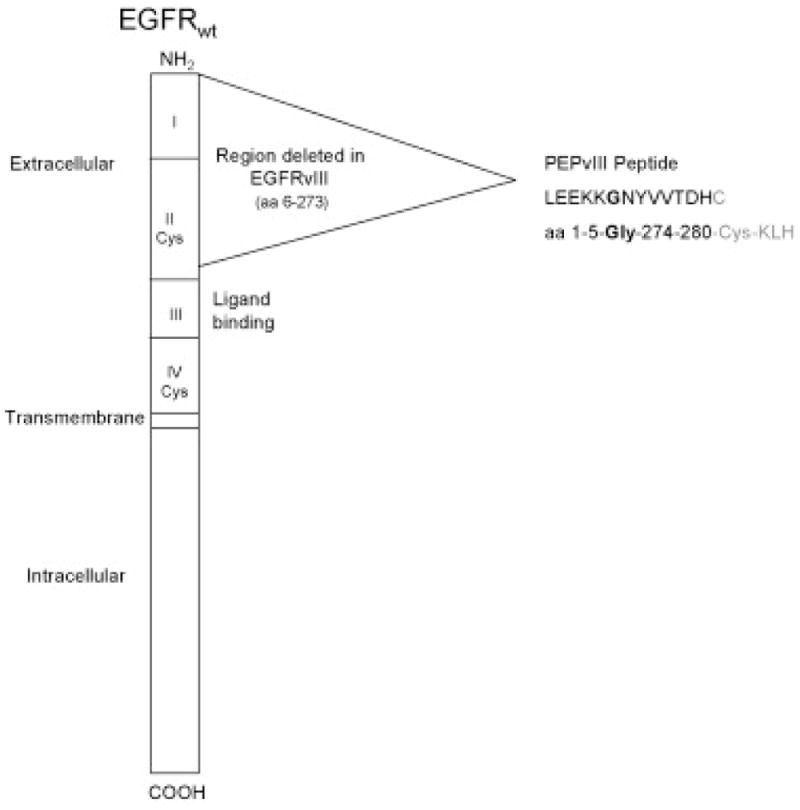

One tumor-specific antigen, EGFRvIII, is consistently expressed in a wide range of malignant cancers, including approximately 40% of GBMs, [81] and it therefore has been the subject of much recent immunotherapy research. EGFRvIII is a truncated form of EGFR, resulting from an 801 base pair in-frame deletion that produces a fusion junction with a novel glycine (Figure 3).[82, 83]

Figure 3. Depiction of wild-type EGFR and the formation of EGFRvIII.

Drawing illustrates the 801 base pair region that is deleted to form EGFRvIII. The inframe deletion occurs in the extracellular portion of the protein, and at the fusion site a novel glycine amino acid codon is created. The peptide used for vaccination studies, PEPvIII, is the 13 amino acid sequence that spans across this fusion region, which contains a tumor-specific epitope including the novel glycine, and is linked to a terminal cysteine which permits conjugation of the peptide to the adjuvant KLH molecule. Reprinted from Semin Immunol, 20(5), Sampson JH, Archer GE, Mitchell DA, Heimberger AB, Bigner DD, Tumor-specific immunotherapy targeting the EGFRvIII mutation in patients with malignant glioma, page 268, copyright 2008, with permission from Elsevier.

Vaccination against EGFRvIII has shown promising results in preclinical studies. Preclinical studies performed in vitro and in vivo in a mouse tumor model demonstrated inhibition of tumor growth with passive administration of the EGFRvIII-specific antibodies and improved long-term survival after cessation of antibody administration.[84] A DC-based vaccine derived from a peptide fragment of EGFRvIII that spans the novel glycine junction (PEPvIII) was subsequently developed. When injected intraperitoneally, this vaccine was efficacious against murine intracerebral tumors and greatly increased the median survival of treated mice.[85] Not only did the majority of vaccinated mice survive without evidence of tumor recurrence, they also survived a repeat challenge of tumor inoculation, suggesting the development of long-term immune memory as well. Clinical trials with this promising vaccine are reviewed in detail below.

Peptide Vaccination Trials

While few peptide vaccination studies have been performed in primary brain tumors; many more have been performed for systemic cancers, like melanoma, that often have CNS metastases. One important clinical trial involved a synthetic peptide vaccine developed from the melanoma-melanocyte differentiation antigen gp100 that was given to patients with metastatic melanoma both with and without IL-2 adminstration.[86] This trial tested vaccination of both the naturally occurring melanoma antigen gp209–217 and a synthetic peptide, called gp209-2M, which is a modified form of this antigen that possesses a greater binding affinity to HLA-A2. Both peptides were administered subcutaneously in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) with and without intravenous IL-2 administration. Treatments prior to study enrollment for these patients included surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and immunotherapy with IL-2, and 82% of study patients had received two or more of these therapies. Objective cancer regression was seen in 1 of 9 (11%) patients who received g209–217 in IFA, 0 of 11 (0%) patients who received g209-2M in IFA, 5 of 12 (42%) patients who received g209–217 in IFA with IL-2, and 8 out of 19 (42%) patients who received g209-2M in IFA with IL-2. For comparison, previous trials of IL-2 alone in 134 melanoma patients showed a 17% response rate.[87] This study proved both that it was possible to generate an antitumor response against a self-antigen and that the combination of the cytokine IL-2 with vaccination improves clinical regression rates when compared to either vaccine or IL-2 alone. Additionally Rosenberg states, “objective regression was seen of metastases in the brain, lung, liver, lymph nodes, muscle, skin and subcutaneous tissues.”[86] This important trial showed the highest published clinical response rate of any peptide vaccination trial for melanoma to date.[88] Other peptide vaccination trials in melanoma have reported response rates ranging from 0 to 28% using multiple different peptides derived from the tumor-associated antigens gp100, MAGE-1, MAGE-3, tyrosinase, and NY-ESO-1 and administered in various adjuvants, including IFA, IL-12, and GM-CSF.[89–95]

In 2004, Rosenberg et al. reviewed multiple cancer vaccine trials in various metastatic cancers.[96] According to his review of National Cancer Institute (NCI) trials that involved peptide vaccines against metastatic melanoma, [94, 97–99] prostate, [100, 101] breast, [101] cervical, [102] and colorectal cancer[103] along with peptide vaccines against multiple cancers, [95, 104, 105] he calculated a total of 7 objective responses, all in melanoma trials, out of 175 patients (4%). This can be separated into a 7.8% response rate in melanoma peptide vaccine trials (7 out of 90 patients) and 0% response rate in all other peptide vaccine trials (0 out of 85 patients). Rosenberg et al. criticized the conclusions of these individual studies, stating that their results were overly optimistic since they relied on surrogate, subjective endpoints rather than using standard tumor response criteria, [96] which should involve objective measurements of lesions.[106, 107] After calculating the adjusted overall numbers, that review criticized cancer vaccine strategies in general due to their poor results in clinical trials so far, and suggested that immunosuppressive mechanisms such as regulatory T-cells may be playing a significant role.[96] Although standard chemotherapy or radiation should deplete the inhibitory regulatory T-cells, at the same time it would also cause systemic lymphodepletion, thereby depleting the effector cells needed to mount a tumoricidal immune response. To eliminate the immunosuppressive cells while maintaining immune cells that can mount an effective antitumor response, Rosenberg et al. suggests that cell transfer therapies may be a more successful immunotherapy strategy. In this approach, systemic lymphodepletion can be performed prior to infusion of the activated cells.

Despite the difficulty with successful translation of active vaccination strategies to the clinic, the pessimism expressed by Rosenberg et al.[96] appears to be somewhat misleading. As previously expressed elsewhere, [108, 109] many of the earlier vaccination “failures” used different response criteria that, if translated into RECIST criteria, may actually appear to have improved results. Additionally, treatment in the neo-adjuvant or adjuvant setting may show more treatment efficacy, and previous vaccine studies have used patients that were already heavily pretreated with chemotherapy, which selects for resistant and aggressive tumors and therefore biases the results towards failure. These authors who have previously responded to these criticisms suggest that future studies may be more successful if more immunogenic tumor antigens are selected, if only patients with minimal burden of disease are treated, or if the vaccines are studied on only specific subsets of patients with particular HLA haplotypes or other immunologic variables.[108, 109] Furthermore, although the results of cell transfer therapy to date have been encouraging, but there has yet to be a significant study that conclusively demonstrates that this form of treatment will extend survival. Additionally, the cost and effort required for this cellular therapy that is personalized to each patient will likely prevent this approach from ever becoming widespread.

The recent experience of an overwhelming immune response to a peptide vaccine against the amyloid-β protein in Alzheimer’s disease demonstrates that peptide vaccination has the ability to affect the CNS environment.[14] Amyloid- β protein is known to be involved in Alzheimer’s disease, although its full role in the disease process has not been completely determined.[110] When antibodies against this protein were passively administered to a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease, clearance of the protein in the CNS occurred and the mice were symptomatically improved.[111, 112] Additionally, after intraperitoneal injection of the antibody, staining was able to conclusively demonstrate that it was present within the CNS.[112]

Multiple theories have been proposed to explain how an antibody could cause clearance of Aβ plaques in the CNS. These theories suggest that either antibodies cross the blood brain barrier and directly dissolve the plaques, [113] or they cross and directly bind to the plaques, which leads to phagocytosis by microglia.[111, 112] A third theory suggests that the antibody actually causes clearance of Aβ plaques near the periphery of the CNS, increasing plasma concentration of Aβ which leads to deeper clearance via diffusion of Aβ due to the resultant concentration gradient.[114] Which of these is the predominant mechanism of action has not been conclusively determined.

When a vaccine targeting this protein was attempted in human clinical trials, antibodies were successfully induced against the Aβ protein. However, levels of antibody titers in serum were not associated with symptom severity and 6% of patients in the trial developed meningoencephalitis, so the trial was stopped early.[115, 116] Analysis of these patients suggests that the Aβ removal was secondary to antibody binding, while the meningoencephalitis was likely caused by a cell-mediated immune response.[117] After death, autopsy of some vaccine trial patients revealed large areas of cortex lacking plaques and decreased average numbers of amyloid plaques when compared to age matched non-immunized controls, although there was no evidence of a difference in survival or time to progression to dementia.[118] It is important to note that the small study size would have made it extremely difficult to see a difference in clinical endpoints. Additionally, these studies revealed that microglia was associated with Aβ antibodies, suggesting that they may be involved in clearance of these plaques.[117]

EGFRvIII Vaccine Trials

Despite the largely unimpressive results of earlier peptide vaccine trials, there have been much more encouraging data coming from our ongoing vaccine studies targeting the tumor-specific antigen, EGFRvIII. As opposed to earlier peptide vaccine trials that targeted tumor-associated antigens, these ongoing studies with the EGFRvIII vaccine may be benefited by the lack of self-tolerance to this tumor-specific antigen. Clinical testing of vaccination against the tumor-specific antigen EGFRvIII began in a Phase I trial (VICTORI) conducted at Duke University Medical Center (PI: John H. Sampson), and continued in a Phase II multi-center trial (ACTIVATE) conducted at Duke (PI: John H. Sampson) and University of Texas, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (PI: Amy B. Heimberger).[119] The Phase I trial, VICTORI, enrolled 20 patients with WHO grade III or IV malignant gliomas, and 16 of these patients were administered vaccine. Production of this vaccine involved autologous dendritic cells pulsed with PEPvIII conjugated to the adjuvant molecule keyhole limpet cyanin (KLH). The DC-based vaccine was delivered via intradermal injection 2 weeks following the end of radiation therapy. Patients in the trial developed both B-cell and T-cell immunity against PEPvIII and EGFRvIII, and the only adverse events that occurred were NCI Common Toxicity Criteria grade I and II local reactions at the injection site. The median survival after histologic diagnosis in the 12 patients with GBM who were treated was 22.8 months, which is significantly longer than both the published median survival of 13.9 months for carmustine wafer treatment, [120] and 14.6 months for temozolomide therapy.[2]

In order to eliminate the prohibitive cost and variability associated with DC-based vaccine production, the subsequent Phase II trial involved vaccination directly with PEPvIII-KLH and granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) without the use of DCs. This change was supported by pre-clinical results that showed a 26% increase in median survival in mice receiving just one vaccination of PEPvIII-KLH in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant and GM-CSF.[121] This Phase II trial entitled, ACTIVATE, enrolled patients with newly diagnosed GBM (WHO grade IV) and used the same timing of initial vaccine delivery as in VICTORI. However, unlike VICTORI, patients in ACTIVATE subsequently received monthly vaccines until evidence of tumor progression. The 18 eligible patients had a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 14.2 months (n = 18) in vaccinated patients compared to median PFS of 6.3 months (n = 17) in historical matched unvaccinated patients (gross total resection without progression during radiation, EGFRvIII+). The vaccinated cohort not only compared favorably with the unvaccinated cohort, but also with concurrent temozolomide and radiation followed by adjuvant temozolomide which reports a median TTP of 6.9 months. Additionally, 100% of the recurrent tumors in the vaccinated cohort showed loss of EGFRvIII expression, suggesting both effective immunological activation and elimination of EGFRvIII+ tumor cells as well as a possible mechanism of treatment failure.[122] The results of the phase II trial confirmed that with these vaccinations, patients developed powerful immune responses against the vaccinating peptide, PEPvIII, and the native protein, EGFRvIII.[123]

A follow-up phase II multicenter trial enrolled 21 patients with newly diagnosed, EGFRvIII+ GBM and treated them with monthly PEPvIII-KLH intradermal vaccinations with concurrent monthly temozolomide on either a 5 day (200 mg/m2) or 21 day (100 mg/m2) regimen following standard surgical resection and combined radiation and temozolomide. The results showed a median PFS of 16.6 months in the patients who received vaccine and concurrent temozolomide, which compared favorably against the median PFS of 14.3 months in a historical matched control group (p<0.0001) and the median PFS of 15.2 months in a subgroup treated with temozolomide alone (p=0.0078).[124] The results from these trials are very encouraging and suggest that vaccination with PEPvIII-KLH can be efficacious in those patients with newly diagnosed GBM whose tumors express the EGFRvIII antigen. These promising results are currently awaiting confirmation in an ongoing phase III study.

Conclusion

So far, the only immune-based treatment against tumors that has made it to standard clinical practice with FDA approval is the passive administration of monoclonal antibodies. As described above, antibodies have been demonstrated to cross the blood brain barrier, and antibody infusions have demonstrated efficacy in treating solid tumors (trastuzumab, cetuximab, bevacizumab). However, cellular infusions and vaccination strategies have both produced encouraging results. Previous attempts at peptide vaccination for Alzheimer’s disease have shown that peptide vaccination has the ability to not only provoke an immune response across the blood brain barrier but that this response can rise to clinically significant levels.

The extent to which antibody versus cell-mediated responses are necessary to eliminate tumors has not been completely determined. As discussed above, both responses were generated in our experience with the EGFRvIII vaccine and also with the amyloid- β peptide vaccine against Alzheimer’s disease. The antibodies that are targeted to tumor-specific antigens that these vaccines produced may have been very important in combating disease. Since there are a number of monoclonal antibodies clinically approved by the FDA for passive administration which have shown efficacy against solid tumors, this suggests that T cell-mediated killing may not be absolutely necessary against tumors. Furthermore, all standard preventative vaccines to prevent infectious disease produce antibody responses. It is difficult to extrapolate from those vaccines however, since they are prophylactic and therefore are given prior to disease exposure, with the sole exception of the rabies vaccine. It is likely that some component of both humoral and cell-mediated responses will be necessary to obtain sustained tumor eradication, but the evidence is mounting in support of the important role played by antibodies in this process.

Since it can be difficult to control an immune response once it has begun, one possible avenue to prevent the immunotherapy from causing overwhelming systemic toxicity is to focus it towards a tumor specific antigen, such as EGFRvIII, where the cross-reactivity with normal cellular antigens should be minimized. The lack of systemic cross-reactivity also may increase the fraction of antibody that penetrates the blood brain barrier. Our initial promising results with peptide vaccination against EGFRvIII are being confirmed in ongoing studies. It is hoped that this treatment will become a significant advance in the treatment of GBM patients.

GBM is a devastating disease and although standard treatment is able to prolong survival, there is an urgent need to find new, more effective therapies. Immunotherapy may provide a solution to this problem. Although passive antibody administration is certainly the most successful immune strategy against existing solid tumors to date, peptide vaccination has also been able to elicit significant anti-tumor responses, via both B-cell and T-cell mediated pathways. The results of ongoing clinical studies will help to clarify the predominant mechanism through which these effects are mediated, and will conclusively determine the magnitude of treatment effect that can be achieved with this treatment approach.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Charles W Kanaly, Email: charles.kanaly@duke.edu, Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Box 3050, 220 Sands Building, Research Drive, Durham, NC 27710, Phone: 919-668-5370, Fax: 919-684-9045.

Dale Ding, Email: dale.ding@duke.edu, School of Medicine, Duke University, DUMC Box 3050, 220 Sands Building, Research Drive, Durham, NC 27710, Phone: 919-668-5370, Fax: 919-684-9045.

Amy B. Heimberger, Email: aheimber@mdanderson.org, University of Texas, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Department of Neurosurgery, Unit 442, 1400 Holcombe Boulevard, FC7.2000, Houston, TX 77030-4009, Phone: 713-792-2400, Fax: 713-794-4950.

John H Sampson, Email: john.sampson@duke.edu, Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, The Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center at Duke, Box 3050, 220 Sands Building, Research Drive, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710, Phone: 919-668-5370, Fax: 919-684-9045.

REFERENCE LIST

- 1.CBTRUS. Statistical Report: Primary Brain Tumors in the United States, 2000–2004. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 10;352(10):987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mocellin S, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V, Lise M, Nitti D. Part I: Vaccines for solid tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2004 Nov;5(11):681–689. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01610-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pejawar-Gaddy S, Finn OJ. Cancer vaccines: accomplishments and challenges. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008 Aug;67(2):93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg SA, Lotze MT, Muul LM, et al. Observations on the systemic administration of autologous lymphokine-activated killer cells and recombinant interleukin-2 to patients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985 Dec 5;313(23):1485–1492. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198512053132327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, White DE, Steinberg SM. Durability of complete responses in patients with metastatic cancer treated with high-dose interleukin-2: identification of the antigens mediating response. Ann Surg. 1998 Sep;228(3):307–319. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fyfe G, Fisher RI, Rosenberg SA, Sznol M, Parkinson DR, Louie AC. Results of treatment of 255 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who received high-dose recombinant interleukin-2 therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1995 Mar;13(3):688–696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.3.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atkins MB, Lotze MT, Dutcher JP, et al. High-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Jul;17(7):2105–2116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg SA. Shedding light on immunotherapy for cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004 Apr 1;350(14):1461–1463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr045001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenberg SA. Progress in human tumour immunology and immunotherapy. Nature. 2001 May 17;411(6835):380–384. doi: 10.1038/35077246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janeway CATP, Walport M, Shlomchik MJ. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 6. New York, NY: Garland Science Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sehgal A, Berger MS. Basic concepts of immunology and neuroimmunology. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9(6):e1. doi: 10.3171/foc.2000.9.6.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medawar PB. Immunity to homologous grafted skin; the fate of skin homografts transplanted to the brain, to subcutaneous tissue, and to the anterior chamber of the eye. Br J Exp Pathol. 1948 Feb;29(1):58–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell DA, Fecci PE, Sampson JH. Immunotherapy of malignant brain tumors. Immunol Rev. 2008 Apr;222:70–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gehrmann J, Matsumoto Y, Kreutzberg GW. Microglia: intrinsic immuneffector cell of the brain. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1995 Mar;20(3):269–287. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)00015-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cserr HF, Harling-Berg CJ, Knopf PM. Drainage of brain extracellular fluid into blood and deep cervical lymph and its immunological significance. Brain Pathol. 1992 Oct;2(4):269–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1992.tb00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zalutsky MR, Moseley RP, Coakham HB, Coleman RE, Bigner DD. Pharmacokinetics and tumor localization of 131I-labeled anti-tenascin monoclonal antibody 81C6 in patients with gliomas and other intracranial malignancies. Cancer Res. 1989 May 15;49(10):2807–2813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott AM, Lee FT, Tebbutt N, et al. A phase I clinical trial with monoclonal antibody ch806 targeting transitional state and mutant epidermal growth factor receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Mar 6;104(10):4071–4076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611693104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perera RM, Zoncu R, Johns TG, et al. Internalization, intracellular trafficking, and biodistribution of monoclonal antibody 806: a novel anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody. Neoplasia. 2007 Dec;9(12):1099–1110. doi: 10.1593/neo.07721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalmau J, Rosenfeld MR. Paraneoplastic syndromes of the CNS. Lancet Neurol. 2008 Apr;7(4):327–340. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70060-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sansing LH, Tuzun E, Ko MW, Baccon J, Lynch DR, Dalmau J. A patient with encephalitis associated with NMDA receptor antibodies. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007 May;3(5):291–296. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bataller L, Dalmau J. Paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes. Neurol Clin. 2003 Feb;21(1):221–247. ix. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(02)00037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalmau J, Bataller L. Clinical and immunological diversity of limbic encephalitis: a model for paraneoplastic neurologic disorders. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2006 Dec;20(6):1319–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenfeld MR, Dalmau J. The clinical spectrum and pathogenesis of paraneoplastic disorders of the central nervous system. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2001 Dec;15(6):1109–1128. vii. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalmau J. Limbic encephalitis and variants related to neuronal cell membrane autoantigens. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2008 Nov;48(11):871–874. doi: 10.5692/clinicalneurol.48.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuzun E, Dalmau J. Limbic encephalitis and variants: classification, diagnosis and treatment. Neurologist. 2007 Sep;13(5):261–271. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31813e34a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenfeld MR, Dalmau J. Current Therapies for Paraneoplastic Neurologic Syndromes. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2003 Jan;5(1):69–77. doi: 10.1007/s11940-003-0023-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bataller L, Dalmau J. Paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes: approaches to diagnosis and treatment. Semin Neurol. 2003 Jun;23(2):215–224. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engelhardt B, Ransohoff RM. The ins and outs of T-lymphocyte trafficking to the CNS: anatomical sites and molecular mechanisms. Trends Immunol. 2005 Sep;26(9):485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wekerle H, Sun D, Oropeza-Wekerle RL, Meyermann R. Immune reactivity in the nervous system: modulation of T-lymphocyte activation by glial cells. J Exp Biol. 1987 Sep;132:43–57. doi: 10.1242/jeb.132.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van den Berg MP, Merkus P, Romeijn SG, Verhoef JC, Merkus FW. Uptake of melatonin into the cerebrospinal fluid after nasal and intravenous delivery: studies in rats and comparison with a human study. Pharm Res. 2004 May;21(5):799–802. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000026431.55383.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merkus P, Guchelaar HJ, Bosch DA, Merkus FW. Direct access of drugs to the human brain after intranasal drug administration? Neurology. 2003 May 27;60(10):1669–1671. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000067993.60735.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bobo RH, Laske DW, Akbasak A, Morrison PF, Dedrick RL, Oldfield EH. Convection-enhanced delivery of macromolecules in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Mar 15;91(6):2076–2080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrison PF, Laske DW, Bobo H, Oldfield EH, Dedrick RL. High-flow microinfusion: tissue penetration and pharmacodynamics. Am J Physiol. 1994 Jan;266(1 Pt 2):R292–305. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.1.R292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sampson JH, Reardon DA, Friedman AH, et al. Sustained radiographic and clinical response in patient with bifrontal recurrent glioblastoma multiforme with intracerebral infusion of the recombinant targeted toxin TP-38: case study. Neuro Oncol. 2005 Jan;7(1):90–96. doi: 10.1215/S1152851703000589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vogelbaum MA, Sampson JH, Kunwar S, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery of cintredekin besudotox (interleukin-13-PE38QQR) followed by radiation therapy with and without temozolomide in newly diagnosed malignant gliomas: phase 1 study of final safety results. Neurosurgery. 2007 Nov;61(5):1031–1037. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000303199.77370.9e. discussion 1037–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rand RW, Kreitman RJ, Patronas N, Varricchio F, Pastan I, Puri RK. Intratumoral administration of recombinant circularly permuted interleukin-4-Pseudomonas exotoxin in patients with high-grade glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000 Jun;6(6):2157–2165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teicher BA. Transforming growth factor-beta and the immune response to malignant disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 Nov 1;13(21):6247–6251. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Houston A, Bennett MW, O’Sullivan GC, Shanahan F, O’Connell J. Fas ligand mediates immune privilege and not inflammation in human colon cancer, irrespective of TGF-beta expression. Br J Cancer. 2003 Oct 6;89(7):1345–1351. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finn OJ. Cancer immunology. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jun 19;358(25):2704–2715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rabinovich GA, Gabrilovich D, Sotomayor EM. Immunosuppressive strategies that are mediated by tumor cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:267–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shevach EM, McHugh RS, Piccirillo CA, Thornton AM. Control of T-cell activation by CD4+ CD25+ suppressor T cells. Immunol Rev. 2001 Aug;182:58–67. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1820104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hori S, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi S. Control of autoimmunity by naturally arising regulatory CD4+ T cells. Adv Immunol. 2003;81:331–371. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(03)81008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 1995 Aug 1;155(3):1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fecci PE, Mitchell DA, Whitesides JF, et al. Increased regulatory T-cell fraction amidst a diminished CD4 compartment explains cellular immune defects in patients with malignant glioma. Cancer Res. 2006 Mar 15;66(6):3294–3302. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davila E, Kennedy R, Celis E. Generation of antitumor immunity by cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope peptide vaccination, CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide adjuvant, and CTLA-4 blockade. Cancer Res. 2003 Jun 15;63(12):3281–3288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003 Jul 31;349(5):427–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vredenburgh JJ, Desjardins A, Herndon JE, 2nd, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Oct 20;25(30):4722–4729. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Korsisaari N, Ross J, Wu X, et al. Blocking vascular endothelial growth factor-A inhibits the growth of pituitary adenomas and lowers serum prolactin level in a mouse model of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Clin Cancer Res. 2008 Jan 1;14(1):249–258. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fuh G, Wu P, Liang WC, et al. Structure-function studies of two synthetic anti-vascular endothelial growth factor Fabs and comparison with the Avastin Fab. J Biol Chem. 2006 Mar 10;281(10):6625–6631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507783200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001 Mar 15;344(11):783–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pestalozzi BC, Zahrieh D, Price KN, et al. Identifying breast cancer patients at risk for Central Nervous System (CNS) metastases in trials of the International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) Ann Oncol. 2006 Jun;17(6):935–944. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stemmler HJ, Heinemann V. Central nervous system metastases in HER-2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer: a treatment challenge. Oncologist. 2008 Jul;13(7):739–750. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin NU, Winer EP. Brain metastases: the HER2 paradigm. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 Mar 15;13(6):1648–1655. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bartsch R, Rottenfusser A, Wenzel C, et al. Trastuzumab prolongs overall survival in patients with brain metastases from Her2 positive breast cancer. J Neurooncol. 2007 Dec;85(3):311–317. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gori S, Rimondini S, De Angelis V, et al. Central nervous system metastases in HER-2 positive metastatic breast cancer patients treated with trastuzumab: incidence, survival, and risk factors. Oncologist. 2007 Jul;12(7):766–773. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-7-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burstein HJ, Lieberman G, Slamon DJ, Winer EP, Klein P. Isolated central nervous system metastases in patients with HER2-overexpressing advanced breast cancer treated with first-line trastuzumab-based therapy. Ann Oncol. 2005 Nov;16(11):1772–1777. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fuchs IB, Loebbecke M, Buhler H, et al. HER2 in brain metastases: issues of concordance, survival, and treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2002 Oct 1;20(19):4130–4133. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stemmler HJ, Schmitt M, Willems A, Bernhard H, Harbeck N, Heinemann V. Ratio of trastuzumab levels in serum and cerebrospinal fluid is altered in HER2-positive breast cancer patients with brain metastases and impairment of blood-brain barrier. Anticancer Drugs. 2007 Jan;18(1):23–28. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000236313.50833.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pestalozzi BC, Brignoli S. Trastuzumab in CSF. J Clin Oncol. 2000 Jun;18(11):2349–2351. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.11.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baculi RH, Suki S, Nisbett J, Leeds N, Groves M. Meningeal carcinomatosis from breast carcinoma responsive to trastuzumab. J Clin Oncol. 2001 Jul 1;19(13):3297–3298. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.zur Hausen H. Human papillomaviruses in the pathogenesis of anogenital cancer. Virology. 1991 Sep;184(1):9–13. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90816-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hislop AD, Taylor GS, Sauce D, Rickinson AB. Cellular responses to viral infection in humans: lessons from Epstein-Barr virus. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:587–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mitchell DA, Xie W, Schmittling R, et al. Sensitive detection of human cytomegalovirus in tumors and peripheral blood of patients diagnosed with glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2008 Feb;10(1):10–18. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Delgado CH, et al. Identification of a human melanoma antigen recognized by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes associated with in vivo tumor rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Jul 5;91(14):6458–6462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Delgado CH, et al. Cloning of the gene coding for a shared human melanoma antigen recognized by autologous T cells infiltrating into tumor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Apr 26;91(9):3515–3519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brichard V, Van Pel A, Wolfel T, et al. The tyrosinase gene codes for an antigen recognized by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes on HLA-A2 melanomas. J Exp Med. 1993 Aug 1;178(2):489–495. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, et al. A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science. 1991 Dec 13;254(5038):1643–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1840703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Visseren MJ, van der Burg SH, van der Voort EI, et al. Identification of HLA-A*0201-restricted CTL epitopes encoded by the tumor-specific MAGE-2 gene product. Int J Cancer. 1997 Sep 26;73(1):125–130. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970926)73:1<125::aid-ijc19>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gaugler B, Van den Eynde B, van der Bruggen P, et al. Human gene MAGE-3 codes for an antigen recognized on a melanoma by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1994 Mar 1;179(3):921–930. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Panelli MC, Bettinotti MP, Lally K, et al. A tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte from a melanoma metastasis with decreased expression of melanoma differentiation antigens recognizes MAGE-12. J Immunol. 2000 Apr 15;164(8):4382–4392. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jager E, Chen YT, Drijfhout JW, et al. Simultaneous humoral and cellular immune response against cancer-testis antigen NY-ESO-1: definition of human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2-binding peptide epitopes. J Exp Med. 1998 Jan 19;187(2):265–270. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang RF, Johnston SL, Zeng G, Topalian SL, Schwartzentruber DJ, Rosenberg SA. A breast and melanoma-shared tumor antigen: T cell responses to antigenic peptides translated from different open reading frames. J Immunol. 1998 Oct 1;161(7):3598–3606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jerome KR, Barnd DL, Bendt KM, et al. Cytotoxic T-lymphocytes derived from patients with breast adenocarcinoma recognize an epitope present on the protein core of a mucin molecule preferentially expressed by malignant cells. Cancer Res. 1991 Jun 1;51(11):2908–2916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ioannides CG, Fisk B, Fan D, Biddison WE, Wharton JT, O’Brian CA. Cytotoxic T cells isolated from ovarian malignant ascites recognize a peptide derived from the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene. Cell Immunol. 1993 Oct 1;151(1):225–234. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1993.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li K, Adibzadeh M, Halder T, et al. Tumour-specific MHC-class-II-restricted responses after in vitro sensitization to synthetic peptides corresponding to gp100 and Annexin II eluted from melanoma cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1998 Sep;47(1):32–38. doi: 10.1007/s002620050501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chaux P, Vantomme V, Stroobant V, et al. Identification of MAGE-3 epitopes presented by HLA-DR molecules to CD4(+) T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1999 Mar 1;189(5):767–778. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.5.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zeng G, Touloukian CE, Wang X, Restifo NP, Rosenberg SA, Wang RF. Identification of CD4+ T cell epitopes from NY-ESO-1 presented by HLA-DR molecules. J Immunol. 2000 Jul 15;165(2):1153–1159. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gilboa E. The promise of cancer vaccines. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004 May;4(5):401–411. doi: 10.1038/nrc1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gilboa E. The makings of a tumor rejection antigen. Immunity. 1999 Sep;11(3):263–270. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moscatello DK, Holgado-Madruga M, Godwin AK, et al. Frequent expression of a mutant epidermal growth factor receptor in multiple human tumors. Cancer Res. 1995 Dec 1;55(23):5536–5539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Libermann TA, Nusbaum HR, Razon N, et al. Amplification, enhanced expression and possible rearrangement of EGF receptor gene in primary human brain tumours of glial origin. Nature. 1985 Jan 10–18;313(5998):144–147. doi: 10.1038/313144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bigner SH, Humphrey PA, Wong AJ, et al. Characterization of the epidermal growth factor receptor in human glioma cell lines and xenografts. Cancer Res. 1990 Dec 15;50(24):8017–8022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sampson JH, Crotty LE, Lee S, et al. Unarmed, tumor-specific monoclonal antibody effectively treats brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 Jun 20;97(13):7503–7508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130166597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Heimberger AB, Archer GE, Crotty LE, et al. Dendritic cells pulsed with a tumor-specific peptide induce long-lasting immunity and are effective against murine intracerebral melanoma. Neurosurgery. 2002 Jan;50(1):158–164. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200201000-00024. discussion 164–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Schwartzentruber DJ, et al. Immunologic and therapeutic evaluation of a synthetic peptide vaccine for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat Med. 1998 Mar;4(3):321–327. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Topalian SL, et al. Treatment of 283 consecutive patients with metastatic melanoma or renal cell cancer using high-dose bolus interleukin 2. JAMA. 1994 Mar 23–30;271(12):907–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Parmiani G, Castelli C, Dalerba P, et al. Cancer immunotherapy with peptide-based vaccines: what have we achieved? Where are we going? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002 Jun 5;94(11):805–818. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.11.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cormier JN, Salgaller ML, Prevette T, et al. Enhancement of cellular immunity in melanoma patients immunized with a peptide from MART-1/Melan A. Cancer J Sci Am. 1997 Jan-Feb;3(1):37–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Schwartzentruber DJ, et al. Impact of cytokine administration on the generation of antitumor reactivity in patients with metastatic melanoma receiving a peptide vaccine. J Immunol. 1999 Aug 1;163(3):1690–1695. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang F, Bade E, Kuniyoshi C, et al. Phase I trial of a MART-1 peptide vaccine with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant for resected high-risk melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1999 Oct;5(10):2756–2765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee P, Wang F, Kuniyoshi J, et al. Effects of interleukin-12 on the immune response to a multipeptide vaccine for resected metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001 Sep 15;19(18):3836–3847. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.18.3836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Marchand M, van Baren N, Weynants P, et al. Tumor regressions observed in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with an antigenic peptide encoded by gene MAGE-3 and presented by HLA-A1. Int J Cancer. 1999 Jan 18;80(2):219–230. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990118)80:2<219::aid-ijc10>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Scheibenbogen C, Schmittel A, Keilholz U, et al. Phase 2 trial of vaccination with tyrosinase peptides and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2000 Mar-Apr;23(2):275–281. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200003000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jager E, Gnjatic S, Nagata Y, et al. Induction of primary NY-ESO-1 immunity: CD8+ T lymphocyte and antibody responses in peptide-vaccinated patients with NY-ESO-1+ cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 Oct 24;97(22):12198–12203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220413497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004 Sep;10(9):909–915. doi: 10.1038/nm1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Slingluff CL, Jr, Petroni GR, Yamshchikov GV, et al. Clinical and immunologic results of a randomized phase II trial of vaccination using four melanoma peptides either administered in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in adjuvant or pulsed on dendritic cells. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Nov 1;21(21):4016–4026. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cebon J, Jager E, Shackleton MJ, et al. Two phase I studies of low dose recombinant human IL-12 with Melan-A and influenza peptides in subjects with advanced malignant melanoma. Cancer Immun. 2003 Jul 16;3:7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Peterson AC, Harlin H, Gajewski TF. Immunization with Melan-A peptide-pulsed peripheral blood mononuclear cells plus recombinant human interleukin-12 induces clinical activity and T-cell responses in advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jun 15;21(12):2342–2348. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Noguchi M, Kobayashi K, Suetsugu N, et al. Induction of cellular and humoral immune responses to tumor cells and peptides in HLA-A24 positive hormone-refractory prostate cancer patients by peptide vaccination. Prostate. 2003 Sep 15;57(1):80–92. doi: 10.1002/pros.10276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vonderheide RH, Domchek SM, Schultze JL, et al. Vaccination of cancer patients against telomerase induces functional antitumor CD8+ T lymphocytes. Clin Cancer Res. 2004 Feb 1;10(3):828–839. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0620-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.van Driel WJ, Ressing ME, Kenter GG, et al. Vaccination with HPV16 peptides of patients with advanced cervical carcinoma: clinical evaluation of a phase I-II trial. Eur J Cancer. 1999 Jun;35(6):946–952. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sato Y, Maeda Y, Shomura H, et al. A phase I trial of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte precursor-oriented peptide vaccines for colorectal carcinoma patients. Br J Cancer. 2004 Apr 5;90(7):1334–1342. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Khleif SN, Abrams SI, Hamilton JM, et al. A phase I vaccine trial with peptides reflecting ras oncogene mutations of solid tumors. J Immunother. 1999 Mar;22(2):155–165. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199903000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tanaka S, Harada M, Mine T, et al. Peptide vaccination for patients with melanoma and other types of cancer based on pre-existing peptide-specific ctotoxic T-lymphocyte precursors in the periphery. J Immunother. 2003 Jul-Aug;26(4):357–366. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200307000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000 Feb 2;92(3):205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.James K, Eisenhauer E, Christian M, et al. Measuring response in solid tumors: unidimensional versus bidimensional measurement. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999 Mar 17;91(6):523–528. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.6.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mocellin S, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V, Marincola FM. Cancer vaccines: pessimism in check. Nat Med. 2004 Dec;10(12):1278–1279. doi: 10.1038/nm1204-1278. author reply 1279–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Timmerman JM, Levy R. Cancer vaccines: pessimism in check. Nat Med. 2004 Dec;10(12):1279. doi: 10.1038/nm1204-1279a. author reply 1279–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wisniewski T, Konietzko U. Amyloid-beta immunisation for Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2008 Sep;7(9):805–811. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70170-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bacskai BJ, Kajdasz ST, Christie RH, et al. Imaging of amyloid-beta deposits in brains of living mice permits direct observation of clearance of plaques with immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2001 Mar;7(3):369–372. doi: 10.1038/85525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bard F, Cannon C, Barbour R, et al. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid beta-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2000 Aug;6(8):916–919. doi: 10.1038/78682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Solomon B, Koppel R, Frankel D, Hanan-Aharon E. Disaggregation of Alzheimer beta-amyloid by site-directed mAb. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997 Apr 15;94(8):4109–4112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.DeMattos RB, Bales KR, Cummins DJ, Dodart JC, Paul SM, Holtzman DM. Peripheral anti-A beta antibody alters CNS and plasma A beta clearance and decreases brain A beta burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Jul 17;98(15):8850–8855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151261398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gilman S, Koller M, Black RS, et al. Clinical effects of Abeta immunization (AN1792) in patients with AD in an interrupted trial. Neurology. 2005 May 10;64(9):1553–1562. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000159740.16984.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Orgogozo JM, Gilman S, Dartigues JF, et al. Subacute meningoencephalitis in a subset of patients with AD after Abeta42 immunization. Neurology. 2003 Jul 8;61(1):46–54. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073623.84147.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nicoll JA, Wilkinson D, Holmes C, Steart P, Markham H, Weller RO. Neuropathology of human Alzheimer disease after immunization with amyloid-beta peptide: a case report. Nat Med. 2003 Apr;9(4):448–452. doi: 10.1038/nm840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Holmes C, Boche D, Wilkinson D, et al. Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunisation in Alzheimer’s disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Lancet. 2008 Jul 19;372(9634):216–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sampson JH, Archer GE, Mitchell DA, Heimberger AB, Bigner DD. Tumor-specific immunotherapy targeting the EGFRvIII mutation in patients with malignant glioma. Semin Immunol. 2008 Oct;20(5):267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Westphal M, Hilt DC, Bortey E, et al. A phase 3 trial of local chemotherapy with biodegradable carmustine (BCNU) wafers (Gliadel wafers) in patients with primary malignant glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2003 Apr;5(2):79–88. doi: 10.1215/S1522-8517-02-00023-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Heimberger AB, Crotty LE, Archer GE, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor VIII peptide vaccination is efficacious against established intracerebral tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2003 Sep 15;9(11):4247–4254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Heimberger A, Hussain SF, Aldape K, et al. Tumor-specific peptide vaccination in newly-diagnosed patients with GBM. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2006 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. 2006;24(18S June 20 Supplement):2529. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Schmittling RJ, Archer GE, Mitchell DA, et al. Detection of humoral response in patients with glioblastoma receiving EGFRvIII-KLH vaccines. J Immunol Methods. 2008 Nov 30;339(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sampson JH, Archer GE, Bigner DD, et al. Effect of EGFRvIII-targeted vaccine (CDX-110) on immune response and TTP when given with simultaneous standard and continuous temozolomide in patients with GBM. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(May 20 suppl) abstr 2011. [Google Scholar]