Abstract

Background:

Fear of side effects and previous negative experiences are common reasons for contraceptive non-use.

Study Design:

We collected information about perceptions of oral contraceptive (OC) safety from 1,271 women 18-49 years old in El Paso, Texas, and compared their responses to a medical evaluation by a nurse practitioner. We also asked participants about their interest in obtaining OCs over-the-counter (OTC).

Results:

Among 794 women potentially at risk of unintended pregnancy, 56.0% said that OCs were medically safe for them. Reasons given for OCs being unsafe related to fears of side effects and prior negative experiences rather than true contraindications. Older women and participants recruited at the less affluent recruitment site were significantly more likely to report that OCs were medically unsafe for them (p<0.05). Non-users who thought OCs were medically unsafe for them were as likely to be medically eligible for use as current hormonal users. Among non-users or non-hormonal users and potential OC candidates (n=601), 60.2% said they would be more likely to use OCs if they were available OTC.

Conclusions:

Women's perception of OC safety does not correlate well with medical eligibility for use. More education about the safety and health benefits of hormonal contraception is needed. OTC availability might contribute to more positive safety perceptions of OCs compared to a prescription environment.

Keywords: oral contraceptives, Latina, misperceptions, over-the-counter provision

1. Introduction

Almost half of all pregnancies in the US are unintended, and this proportion remained unchanged between 1994 and 2001 [1]. Among poor women in the US, Latinas have the highest prevalence of unintended pregnancy compared to African-American and non-Latina white women [1]. Although unintended pregnancy has multiple determinants, contraceptive non-use and method failure are both more common among Latinas compared to non-Latina whites [2,3].

Surveys from the US and other countries have found that health concerns are a common reason why women choose not to contracept. In an analysis of data from 13 countries, health concerns were the second most frequently cited reason for contraceptive non-use after lack of knowledge [4]. Using information from the Demographic and Health Surveys from 12 countries, Bongaarts and Bruce [4] estimated that health concerns reduced the prevalence of oral contraceptive use by approximately 71%.

Several studies in the US have found that Latinas commonly cite fears related to hormonal contraception as a reason for non-use [5]. A survey in Houston, Texas, found that Latinas were significantly less likely to have ever used highly effective contraceptive methods compared to non-Latina whites, and 53% cited a belief that using birth control leads to major side effects as a barrier to use [6]. Focus groups with young Latinas found that concerns about side effects, whether or not they had actually been experienced, were commonly cited as reasons they were not using contraception [7]. In another focus group study in California, Spanish-speaking Latinas were less likely to think the Pill was safe than English-speaking Latinas or whites [8]. Women's fears about the methods vary from valid concerns about common side effects, such as abnormal bleeding, to unfounded myths, such as a belief that OCs do not dissolve after ingestion [7]. These findings are similar to those reported among a rural Mexican population in the 1970s, where fears of contraceptive side effects were most prevalent among women with little knowledge of family planning methods or reproductive physiology [9].

Low-dose combined (OCs) are safe medications, although there are certain medical conditions that are considered contraindications to use. The World Health Organization (WHO) Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) for Contraceptive Use cites several contraindications, including hypertension and other cardiovascular conditions, smoking at age 35 years and over, and breast cancer, among others [10]. Although contraindications are rare among women attending family planning clinics [11], our research among a convenience sample of Latinas age 18 to 49 years in Texas found the prevalence of contraindications to be 36.9% among non-pregnant participants [12]. The high prevalence of contraindications found in this study may be related to the older age of the sample and the low proportion of women using hormonal contraception. It is likely that many women in the sample had not been screened previously for contraindications [12].

When women cite health concerns as a reason for discontinuing or avoiding hormonal contraception, it is unclear if they are making an educated assessment of their true risk or if they are overestimating the dangers associated with use. Most analyses assume the latter, although little research has examined whether women's perceptions of OC safety correlate with actual risk. For this analysis, we aimed to determine whether women's health concerns related to OCs were medically justified by comparing their responses to a health evaluation by a nurse practitioner. A better understanding of women's perceived risks of hormonal contraception could help tailor education interventions aimed at improving uptake of these methods among women for whom these methods are safe.

2. Materials and methods

The data used for this analysis were collected as part of a study evaluating the accuracy of a self-screening checklist for contraindications to OCs, which has been reported separately [12]. We recruited a convenience sample of women between the ages of 18 and 49 years in El Paso, Texas, between April and August 2006 at two public shopping malls and an outdoor flea market. Interviewers asked participants about basic demographic information as well as their current contraceptive use. Women who were not using combined hormonal contraceptives were asked the following:

“Now I'm going to ask you a hypothetical question. As you probably know, some women should not take birth control pills because they have certain diseases or medical conditions that might make it more likely for them to develop a problem while taking the Pill. Let's assume for a minute that you wanted to use the Pill for birth control. Which of the following would apply to you?

In my case, taking the Pill would be bad for my health.

In my case, taking the Pill would NOT be bad for my health.

Not sure.”

Women who said the pill would be bad for their health or who were not sure were then asked about their reasons for this assessment. Two investigators (DG and LF) reviewed these reasons and classified them either as likely true contraindications according to the WHO MEC, or not likely true contraindications. We asked women who were not using contraception or who were only using a barrier method if they thought they would be more likely to use OCs if they could obtain them over the counter in El Paso without a prescription. Women were then given a checklist of medical contraindications to OC use and were asked to check whether they had one or more of these conditions. The checklist was based on the WHO MEC for relative and absolute contraindications to combined oral contraceptives (category 3 and 4 contraindications [10] and has previously been described in detail [12].

After completing the questionnaire, a female nurse practitioner, who was blinded to the woman's interview responses, screened the participant for contraindications to OC use. The clinicians also used a checklist to identify category 3 and 4 contraindications according to the WHO MEC [10] to assess the respondent's actual eligibility to use OCs. The nurse practitioner measured the respondent's blood pressure twice either manually or using an automated Omron HEM-705CP blood pressure monitor (Omron Healthcare, Inc., Bannockburn, Illinois); mean systolic and mean diastolic blood pressures were recorded. Based on this information, the nurse practitioner determined if the respondent would be eligible for OC use. If the provider felt that additional tests or evaluation were necessary before prescribing this method, she classified the participant as contraindicated. Women who were hypertensive and those who were using combined hormonal contraception who were found to be contraindicated were advised to speak with their clinician and were given information about local free or low-cost health clinics.

Participants received a $5-$10 gift card valid for use at the shopping center or flea market for their participation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Texas at El Paso. We obtained verbal informed consent from all participants.

We analyzed the data using Stata v.9.2 (College Station, Texas). We used univariate descriptive statistics to present participants' demographic characteristics and their distribution of responses regarding contraceptive use, self-assessed eligibility for OCs, and reasons for considering OCs unsafe.

Logistic regressions were used to model the demographic and socioeconomic factors associated with two categorical outcomes. The first outcome is women's perceptions regarding the safety of OCs. For this analysis we included only women whom the clinician found to be medically eligible for combined hormonal contraception and who were potentially at risk of unintended pregnancy (n=377). Since the three categorical answers outlined above can be meaningfully ordered from low to high perception of health risk (from “taking the Pill would NOT be bad for my health” to “not sure” to “taking the Pill would be bad for my health”), we performed an ordered logit. Ordered logit models show how independent variables are associated with a participant being higher or lower on the scale of interest [13]. The second outcome was coded as a dichotomous response (“Yes” vs “No” or “Not sure”) to the question: “If the birth control pill were available here in El Paso in a pharmacy without a prescription, do you think you would be more likely to take the Pill?” For this analysis we used two regression models. The first regression included demographic and socioeconomic variables, plus the women's use of contraception (non-hormonal or none) and the clinician's assessment of medical eligibility for OCs use. The second model also included women's perception of OC safety as a covariate.

4. Results

We recruited a total of 1,271 women to participate in the study. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the entire sample of study participants, as well as those who were considered to be potentially at risk of unintended pregnancy. We focused this analysis on the latter group of women because those not at risk of unintended pregnancy may have answered the question about perceived safety of OCs in light of their lack of need for contraception. We identified those potentially at risk of unintended pregnancy (n=794) by excluding women who reported they were pregnant, trying to get pregnant, infertile or sterilized (n=477). On average, the participants were in their early thirties and overwhelmingly Latina (92%). We recruited the largest proportion of participants at the two shopping malls, which are El Paso's largest and cater to consumers from Mexico as well as the US. Approximately one third of participants were recruited from an outdoor flea market that features a variety of new and used merchandise at reputedly bargain prices. Women at risk of unintended pregnancy were similar to the full sample, although they were somewhat younger and had lower parity.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants

| Potentially at risk of unintended pregnancy* (N=794) |

Full sample (N=1,271) |

|

|---|---|---|

| % | % | |

| Age, years | ||

| <25 | 36.7 | 25.6 |

| 25-34 | 35.5 | 31.8 |

| 35-49 | 27.8 | 42.6 |

| Mean/median age | 29.4/27.0 | 32.6/32.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Latina | 90.6 | 91.8 |

| African American | 2.5 | 2.2 |

| White | 4.7 | 4.3 |

| Other | 2.3 | 1.7 |

| Primary language used at home | ||

| Spanish | 50.5 | 52.2 |

| English and Spanish, equally | 12.2 | 12.0 |

| English | 37.3 | 35.7 |

| Primary country of residence | ||

| United States | 81.1 | 80.8 |

| US and Mexico, equally | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Mexico | 17.4 | 17.6 |

| Other | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Education | ||

| Incomplete high school or less (0-11 yrs) | 14.1 | 18.3 |

| Completed high school | 24.7 | 24.5 |

| Some college (13-15 yrs) | 30.0 | 27.9 |

| College or more | 31.2 | 29.4 |

| Mean/median years of schooling | 13.5/14.0 | 13.2/13.0 |

| School location for last grade completed | ||

| United States | 70.7 | 67.5 |

| Mexico | 27.4 | 31.0 |

| Other | 1.9 | 1.5 |

| Parity | ||

| Nulliparous | 46.8 | 33.5 |

| One | 18.8 | 15.1 |

| Two | 22.1 | 26.9 |

| Three or more | 12.4 | 24.5 |

| Mean/median parity | 1.0/1.0 | 1.5/2.0 |

| Recruitment site | ||

| Mall A | 50.3 | 46.7 |

| Mall B | 21.5 | 21.4 |

| Flea market | 28.2 | 31.9 |

Excludes women who are pregnant, trying to get pregnant, infertile or sterilized.

Table 2 shows the contraceptive methods participants reported they were using at the time of the interview. About 17% used combined hormonal methods, mostly in the form of OCs, and an additional 3.4% reported using depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) injections. Sixty-nine percent of women using hormonal contraception reported obtaining it at a clinic or with a prescription, while 31% reported obtaining it at a Mexican pharmacy without a prescription. Non-hormonal methods, mostly condoms, were reported by 11% of women. Sterilization was reported by 28%, and 39% percent said they were not using a contraceptive method. Most of the non-users said they were not currently sexually active (18% of study participants).

Table 2.

Current contraceptive use (n=1,271)

| N | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| DMPA injection | 43 | 3.4 |

| Combined hormonal methods | 209 | 16.5 |

| Oral contraceptive pills | 192 | 15.1 |

| Patch | 15 | 1.2 |

| Vaginal ring | 2 | 0.2 |

| Non-hormonal methods | 139 | 10.9 |

| Condoms | 115 | 9.1 |

| Cap, diaphragm, spermicides | 7 | 0.6 |

| Rhythm/withdrawal | 17 | 1.3 |

| IUD | 35 | 2.8 |

| Sterilized | 349 | 27.5 |

| None | 496 | 39.0 |

| Currently pregnant | 60 | 4.7 |

| Currently seeking pregnancy | 47 | 3.7 |

| Sterile | 32 | 2.5 |

| Not sexually active | 228 | 17.9 |

| Other | 129 | 10.2 |

Among 794 women potentially at risk of unintended pregnancy, 56.0% said that OCs were medically safe for them, while 30.9% believed the pill was medically unsafe and 13.2% were not sure. Using the ordered logit model, we found that age and place of recruitment (a proxy for socioeconomic characteristics of study participants) were significantly associated with the perception that OCs are not medically safe (findings not shown but available upon request). In particular, the odds of perceiving OCs as unsafe were 69% higher for women ages 30 years and older than for younger women, and 59% higher among women who were recruited in the flea market compared to those interviewed in malls (p<0.05). Table 3 shows that the majority of respondents who considered OCs unsafe, or who were not sure, cited fears of side effects, prior negative experiences with the method, or conditions that were not considered true medical contraindications according to the WHO MEC. Only 11% of the participants who said OCs were unsafe referred to conditions that were considered true contraindications by the WHO MEC.

Table 3.

Reasons given for OCs being unsafe (n=348)*

| N | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| True contraindications | ||

| Medical condition | 15 | 4.3 |

| Current smoker | 11 | 3.2 |

| History of serious complication with oral contraceptives | 6 | 1.7 |

| Would seek medical advice first | 12 | 3.4 |

| Not true contraindications | ||

| Concerns about side effects | 68 | 19.5 |

| Previous negative experience with oral contraceptives | 59 | 17.0 |

| Conditions that are not medical contraindications | 13 | 3.7 |

| Too old | 17 | 4.9 |

| History of taking oral contraceptives for too long | 2 | 0.6 |

| Other reasons | ||

| No need for oral contraceptives | 15 | 4.3 |

| Personal/religious reasons | 27 | 7.8 |

| Not sure | 44 | 12.6 |

| No reason given | 59 | 17.0 |

Excludes women who are pregnant, trying to get pregnant, infertile or sterilized.

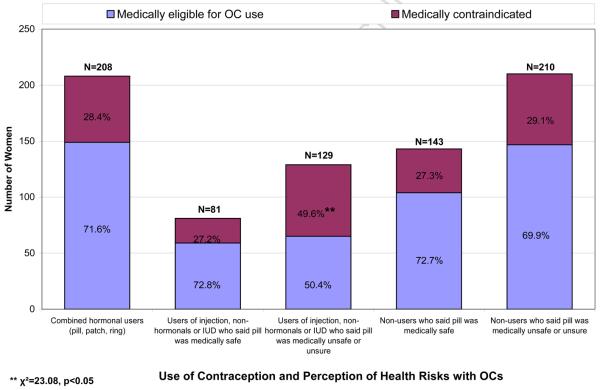

Fig. 1 presents the results of the clinician's evaluation for contraindications to OC use according to participants' current contraceptive method and their perceptions of OCs safety. Surprisingly, we found that 28.4% of women currently using OCs, the patch or the vaginal ring had at least one contraindication to combined hormonal contraception. The most common contraindications were suspected migraine with aura (14.4%) and hypertension (12.5%). The prevalence of contraindications was not significantly different between women who obtained combined hormonal contraception at clinics or with a prescription compared to those who obtained them in a Mexican pharmacy without a prescription (data not shown). Among women who were using a contraceptive method other than the pill, patch or ring, and who believed that OCs were medically safe for them, the clinician found a similar proportion (27.2%) to be contraindicated. Among women who were using a contraceptive method other than the pill, patch or ring and who believed OCs were not medically safe for them or who were unsure, a significantly higher proportion (49.6%) were found to be truly contraindicated by the clinician (p<0.05). However, among contraceptive non-users, those who said the pill was safe and those who said it was unsafe or were unsure were equally likely to have a contraindication, and the proportion contraindicated was similar to that found among current combined hormonal users.

Figure 1.

Choice of Contraception by Medical Assessment for OC Eligibility

Among women not using contraception or those using barrier methods, rhythm or withdrawal (n=601), most respondents (60.2%) said they would be more likely to use OCs if they were available over the counter (OTC), while 35.8% said they would not, and 4% were not sure. In the first regression model, women not currently using a contraceptive method were more likely than users of non-hormonal methods to say they might use the pill if available OTC (adjusted odds ratio 1.54), while those who were medically contraindicated were less likely than women who were considered eligible for pill use to say they wanted OTC access (adjusted odds ratio 0.70) (p<0.05). In the second model, we included women's perception of OC safety as a covariate, which became the only significant predictor. Women who said they thought the pill was safe for them or were not sure were significantly more likely than those who believed it to be dangerous to say that they would use OCs if they were available OTC (adjusted odds ratios 5.94 and 3.92, respectively; p<0.05). (Regression models not shown but available on request).

5. Discussion

This is the first study to our knowledge that evaluated the medical validity of women's perceptions about the safety of hormonal contraception. We found that a minority of women who said the Pill was medically unsafe for them actually cited a true contraindication, and most referred to concerns about side effects they had not experienced, previous negative experiences or conditions that were not true contraindications. Most troubling was the finding that the safety perception of women not using contraception was particularly inaccurate. While contraceptive users who said the Pill was unsafe were significantly more likely to be contraindicated, non-users who said it was unsafe were just as likely to be medically eligible for use as current Pill users. Concerns about side effects and inaccurate knowledge about contraindications may be a particularly significant barrier to starting hormonal contraception for some women.

These findings build on our prior analysis, which demonstrated that the unaided question about OC safety had poor accuracy [12]. We found in that study that women's self-assessment of eligibility for OC use aided by a checklist of true contraindications to OCs was relatively accurate compared to a clinician's evaluation [12]. Future research should examine whether such a checklist or other simple written materials can improve women's perception of the safety of hormonal contraception. Given prior findings that Latinas frequently rely on friends or family rather than medical personnel for information about contraception [7,8], studies should also examine the impact of using peer counselors or promotoras to inform women about the safety and efficacy of contraceptive methods. Promotoras have been shown to be effective to increase behaviors that reduce cardiovascular risk [14], as well as to improve uptake of screening for breast and cervical cancer [15,16].

As noted previously [12], we found a surprisingly high prevalence of contraindications to OCs in this sample. The prevalence is likely high because we included older women in the sample, and because participants were not seeking contraception. In addition, the nurse practitioners might have over-diagnosed certain contraindications, such as hypertension, since blood pressure was measured on a single day, and migraine with aura, which is difficult to assess with a limited number of questions. Still, it is interesting that 28% of women currently using combined hormonal contraception were found to be contraindicated, regardless of whether they obtained the method from a clinician or OTC at a Mexican pharmacy. This suggests that clinician screening may not be perfect and may miss some contraindicated women, or some women may become contraindicated after they are screened. A previous analysis from the US suggested that 6% of current OC users were actually contraindicated for use, although the dataset included only a minority of true contraindications [17].

Not surprisingly, nearly 50 percent of the women who believed OCs to be medically unsafe for themselves, and who were using a contraceptive method other than the pill, patch or ring, were found to be truly contraindicated by the clinician. This is likely because women using a contraceptive method would have received some evaluation from a clinician, and therefore their self-assessment about their medical eligibility for using OCs might be well-informed. However, contraceptive non-users who said the pill was bad for their health were no more likely to be contraindicated than combined hormonal users, suggesting that non-users were not able to self-assess their eligibility for OCs on their own. Instead, they may have been basing their assessment on incorrect information.

We found that 60% of women not currently using a highly effective contraceptive method said they thought they would be more likely to start OCs if the method were available in El Paso without a prescription. This proportion is higher than the 41% of non-users who said in a nationally representative phone survey that they would start the pill, patch or ring if it were available directly from a pharmacy [18]. Interest in OTC access in this population might be higher because this option is more familiar to them. Many participants were of Mexican origin, and El Paso is on the border with Mexico, where OCs are available in pharmacies without a prescription. It is interesting that non-users and women without contraindications were significantly more likely to express interest in OTC access, suggesting that contraceptive prevalence would increase if pills were available OTC without exposing women to excessive risk. However, interest in OTC access is significantly lower among those who view the pill as being unsafe for them, suggesting that OTC access would not combat the prevalent negative perceptions we identified in this study. Other research has found that people commonly view OTC medications as safe [19,20], and it is possible that if OCs were actually available OTC in the US that perceptions of safety would improve. Additional research is needed to explore all of these hypotheses.

This study has several limitations. It is based on a convenience sample drawn from a population that may be less likely to undergo health maintenance screening and therefore more likely to have unrecognized hypertension than the general population of the US. In addition, some of the nurse practitioners in this study had less experience prescribing hormonal contraception than others and might have been more likely to say that a woman needed additional evaluation before being prescribed OCs.

We found that women's health concerns related to hormonal contraception do not necessarily equate with medical ineligibility for use of these methods. Prior studies have also documented that inaccurate knowledge and misperceptions regarding OCs are prevalent [6,7,9]. More research is needed to understand how women create and act on these perceptions. For women who believed the Pill was medically unsafe for them due to prior negative experiences, it is unclear what measures were taken at the time of the episode, such as discussing their symptoms with a clinician, taking medication to manage them or changing formulations. We also found that women's perceptions were not always based on actual experience but instead on what others had told them. In addition to the development of more acceptable contraceptive methods, efforts to improve uptake and continuation of effective contraception must also focus on how to better inform women about reproductive physiology, normal side effects and the non-contraceptive benefits of existing methods.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD047816), as well as by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. We would like to thank Tina Mayagoitia, Cate McNamee and Kari White for their assistance with data collection and analysis. A version of this manuscript was presented at the 2007 annual meeting of the Association for Reproductive Health Professionals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:90–6. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frost JJ, Singh S, Finer LB. Factors associated with contraceptive use and nonuse, United States, 2004. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007;39:90–9. doi: 10.1363/3909007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kost K, Singh S, Vaughan B, Trussell J, Bankole A. Estimates of contraceptive failure from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Contraception. 2008;77:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bongaarts J, Bruce J. The causes of unmet need for contraception and the social content of services. Stud Fam Plann. 1995;26:57–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivera CP, Méndez CB, Gueye NA, Bachmann GA. Family planning attitudes of medically underserved Latinas. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16:879–82. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Ali N, Posner S, Poindexter AN. Disparities in contraceptive knowledge, attitude and use between Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites. Contraception. 2006;74:125–32. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilliam ML, Warden M, Goldstein C, Tapia B. Concerns about contraceptive side effects among young Latinas: a focus-group approach. Contraception. 2004;70:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guendelman S, Denny C, Mauldon J, Chetkovich C. Perceptions of hormonal contraceptive safety and side effects among low-income Latina and non-Latina women. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4:233–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1026643621387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shedlin MG, Hollerbach PE. Modern and traditional fertility regulation in a Mexican community: the process of decision making. Stud Fam Plann. 1981;12:278–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. 3nd ed. WHO; Geneva: 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shotorbani S, Miller L, Blough DK, Gardner J. Agreement between women's and providers' assessment of hormonal contraceptive risk factors. Contraception. 2006;73:501–6. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grossman D, Fernandez L, Hopkins K, Amastae J, Garcia SG, Potter JE. Accuracy of self-screening for contraindications to combined oral contraceptive use. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;112:572–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818345f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snedker K, Glynn P, Wang C. Ordered/Ordinal Logistic Regression with SAS and Stata. University of Washington; 2002. Accessed online on July 2009 at http://staff.washington.edu/glynn/olr.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balcázar H, Alvarado M, Cantu F, Pedregon V, Fulwood R. A promotora de salud model for addressing cardiovascular disease risk factors in the US-Mexico border region. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6:A02. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welsh AL, Sauaia A, Jacobellis J, Min SJ, Byers T. The effect of two church-based interventions on breast cancer screening rates among Medicaid-insured Latinas. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2:A07. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen LK, Feigl P, Modiano MR, et al. An educational program to increase cervical and breast cancer screening in Hispanic women: a Southwest Oncology Group study. Cancer Nurs. 2005;28:47–53. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200501000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shortridge E, Miller K. Contraindications to oral contraceptive use among women in the United States, 1999-2001. Contraception. 2007;75:355–60. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landau SC, Tapias MP, McGhee BT. Birth control within reach: a national survey on women's attitudes toward and interest in pharmacy access to hormonal contraception. Contraception. 2006;74:463–70. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wazaify M, Shields E, Hughes CM, McElnay JC. Societal perspectives on over-the-counter (OTC) medicines. Fam Pract. 2005;22:170–6. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes L, Whittlesea C, Luscombe D. Patients' knowledge and perceptions of the side-effects of OTC medication. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:243–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]