Abstract

Background

The EQ-5D has been extensively used to assess patient utility in trials of new treatments within the cardiovascular field. The aims of this study were to review evidence of the validity and reliability of the EQ-5D, and to summarise utility scores based on the use of the EQ-5D in clinical trials and in studies of patients with cardiovascular disease.

Methods

A structured literature search was conducted using keywords related to cardiovascular disease and EQ-5D. Original research studies of patients with cardiovascular disease that reported EQ-5D results and its measurement properties were included.

Results

Of 147 identified papers, 66 met the selection criteria, with 10 studies reporting evidence on validity or reliability and 60 reporting EQ-5D responses (VAS or self-classification). Mean EQ-5D index-based scores ranged from 0.24 (SD 0.39) to 0.90 (SD 0.16), while VAS scores ranged from 37 (SD 21) to 89 (no SD reported). Stratification of EQ-5D index scores by disease severity revealed that scores decreased from a mean of 0.78 (SD 0.18) to 0.51 (SD 0.21) for mild to severe disease in heart failure patients and from 0.80 (SD 0.05) to 0.45 (SD 0.22) for mild to severe disease in angina patients.

Conclusions

The published evidence generally supports the validity and reliability of the EQ-5D as an outcome measure within the cardiovascular area. This review provides utility estimates across a range of cardiovascular subgroups and treatments that may be useful for future modelling of utilities and QALYs in economic evaluations within the cardiovascular area.

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) imposes a great burden on societies around the world, with an estimated 16.7 million - or 29.2% of total global deaths - resulting from various forms of CVD[1]. A recent study estimated the total costs of CVD in the European Union, in terms of health care expenditure and lost productivity, to be €169bn a year [2]. Major CVDs include coronary heart disease (CHD), cerebrovascular disease, hypertension and heart failure. In addition, CVD has a significant impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients who survive coronary events such as heart attacks (myocardial infarction) or stroke. It has been suggested that HRQoL measures (i.e. measures that refer to a patient's emotional, social and physical wellbeing) are particularly useful with respect to investigating treatment of CVD in three instances: 1) when results of clinical trials show little evidence of a major improvement in survival so that choice of therapy will be determined on the basis of quality of life measurement; 2) when a treatment is effective in reducing mortality, but has toxic or unacceptable side effects so that quality of life measurement may help physicians and their patients weight the benefits and risks of such a treatment; 3) when patients are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, the morbidity and mortality rates are low, and the therapy is long term[3].

Increasingly over time, clinical trials within the cardiovascular field have included HRQoL measures. Such measures, alongside clinical measures of functionality, can help evaluate the physical, mental and emotional implications of CVD as well as the effects of surgical and medical treatments. Commonly used functional classification systems within the cardiovascular field are the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification system for heart failure patients and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) grading scale for angina pectoris[4,5]. HRQoL measurement in CVD can be assessed using disease-specific instruments such as the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ); MacNew Heart Disease Health-related Quality of Life Questionnaire; and the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure score (MLHF) [6-8]. These questionnaires are particularly sensitive to changes in aspects of HRQoL directly related to CVD. Alternatively, commonly used generic measures of HRQoL including the SF-6D, Health Utilities Index (HUI) and the EQ-5D have also been used in CVD studies [9-11]. The main advantages of such generic multi-attribute health state classifiers are that they allow the calculation of Quality adjusted life years (QALYs) within cost-utility analyses as well as allowing comparison of HRQoL across different conditions and against age-sex matched population norms.

Among the available generic measures, the EQ-5D has gained widespread use due to its simplicity to administer, score and interpret. It also imposes minimal burden on the respondent as it is a brief, simple measure for patients to understand and to complete. The index-based score is generated by applying societal preference weights to the health state classification completed by the patient that consists of five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression), each with three levels of response or severity (no problems, some problems, or extreme problems). The ability to convert self classification responses into a single index score makes the EQ-5D practical for clinical and economic evaluation[11]. The index-based score is typically interpreted along a scale where 1 represents best possible health and 0 represents dead, with some health states valued as being worse than dead (<0). In addition to the index-based scoring system, the visual analogue scale (VAS) component of the EQ-5D enables the patient to place their current health state on a range from 0 (worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best imaginable health state). Algorithms have been developed based on societal preferences for health states, with the most popular being based on the UK-based population[12], although many other country-specific algorithms are also available [13-18].

The principle aims of this paper were: to synthesise the evidence on the validity and reliability of the EQ-5D in studies within the cardiovascular field; to summarise the EQ-5D based scores reported in studies within the CVD field; and to attempt to stratify mean utility scores according to level of disease severity.

Methods

Data Collection and Assessment

A computerised search of the current published literature was performed using MEDLINE and EMBASE for the period January 1988 to October 2008. The search strategy combined exploded or medical subject headings relating to the CVD field and the EQ-5D as follows: ('cardiovascular'/exp OR 'cardiovascular') OR ('cardiac'/exp OR 'cardiac') OR ('cardiology'/exp OR 'cardiology') AND 'euroqol' OR 'EQ 5D' OR 'EQ5D'. The EuroQol website http://www.euroqol.org was also used to identify unique references, including working papers and conference proceedings that may not have been captured in the initial literature search. Only full-text published papers were included for analysis.

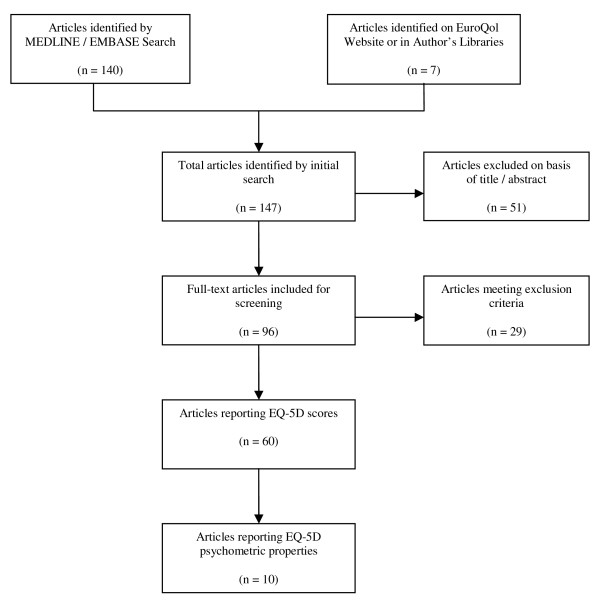

The inclusion criteria required that the paper was original research, and that it reported EQ-5D scores specific to cardiovascular disease or reported psychometric properties of the EQ-5D in a population with cardiovascular disease. Studies that only reported EQ-5D index or VAS scores graphically in terms of change over time were excluded from the analysis. When multiple studies used the same dataset, EQ-5D scores were only reported from one article to avoid double counting. No language restrictions were imposed. Study abstracts that potentially met the inclusion criteria were identified, and full-text articles were retrieved for further review. A standard data abstraction form was developed to facilitate the structured review, which included study design, patient characteristics, intervention information, published source of index-based preference weights and EQ-5D scores as well as details of any other clinical measures; disease-specific quality of life and generic HRQoL instruments. A summary of the results of the literature search is provided in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Summary of literature search.

Data Analysis

Initially, studies that reported EQ-5D index-based scores and/or VAS scores were sorted into cardiovascular subgroups (e.g. Angina/Myocardial Infarction/CHD etc) that were informed by the latest WHO International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10: I00-I99 - diseases of the circulatory system) (Table 1 in Additional file 1) [19]. Confidence intervals were calculated from the sample size and standard deviation (SD) or the standard error when not reported directly in the paper. Scores that were not reported using the appropriate range of scale were transformed, i.e. index-based scores anchored by 0 (dead) and 1 (full health), VAS scores range from 0 (dead) to 100 (full health). If EQ-5D results were stratified (e.g. by age, sex and disease severity), results were only reported once, using the most clinically relevant stratification: CCS angina classification; NYHA heart failure classification or demographic characteristics (% of males/females and mean age of patient cohort). Error bars in Figures 2 and 3 represent 95% confidence intervals around the mean score, which were calculated from the reported SD and sample size. There was no attempt to combine estimates from different studies in a formal meta-analysis since the main objective was to contrast studies with different features and to explain heterogeneity in the results. The degree of heterogeneity between studies was quantified using the I2 statistic [20]. The I2 statistic uses the sum of the squared differences of each study from the pooled estimate and the degrees of freedom of the test to provide a measure of the percent of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity between studies. A meta-analysis yielding a value of I2 above 75% suggests a high level of heterogeneity between the studies. Psychometric properties were summarised according to the type of property assessed (validity/reliability/responsiveness), the comparison performed, and the statistical test result.

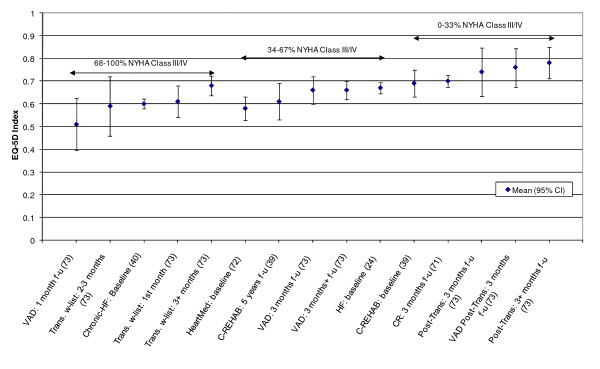

Figure 2.

EQ-5D Index Mean scores for Heart Failure patients - Stratified by baseline disease severity (NYHA class).

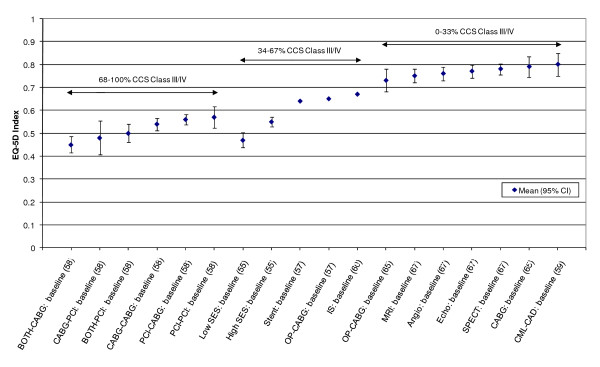

Figure 3.

EQ-5D Index Mean scores for IHD patients - Stratified by baseline disease severity (CCS class).

Results

The electronic search of databases returned 147 papers of which 66 met the selection criteria. 60 publications reported an EQ-5D index score, VAS score and/or responses to the self-classification system, whilst 10 papers presented evidence of the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D (Figure 1).

Overall, there was wide variation in terms of CVD subgroups, disease stage, age distribution and other methodological aspects (Table 1 in Additional file 1). Of studies reporting mode of administration (n = 41), 42% were filled out on-site by respondents, 52% were mailed-out questionnaires, and 6% were administered via telephone interview. Overall, there was an equal mix of randomised controlled trial (RCT) and observational study designs. Prospective observational study designs were more common than retrospective (69% vs. 31%) and there was an equal mix of longitudinal and cross-sectional studies. The majority of studies (52%) reported EQ-5D index scores using the UK-based algorithm although scores based on Czech, Danish, Dutch, German, US and European preferences were also used [13-18]. However, a number of studies (33%) did not explicitly state the algorithm used to calculate the index score.

Studies of cardiovascular patients that reported psychometric properties of the EQ-5D (n = 10) explored construct validity (convergent and discriminative), typically in terms of correlations with other disease-specific HRQoL measures as well as reliability and responsiveness (Table 2 in Additional file 1). Evidence of validity and reliability were reported in studies of ischaemic heart disease (n = 3); cerebrovascular disease (n = 3); heart failure (n = 2) and peripheral vascular disease (n = 2). Convergent validity was the most common property assessed, using Spearman rank correlations to explore associations with another measure. Reliability and responsiveness were generally measured by test-retest statistics; intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) and effect size (ES). In terms of construct validity, comparisons were made between the EQ-5D and disease specific questionnaires such as the Barthel Index (BI), Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), MacNew Heart Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire, NYHA and VascuQol as well as other generic measures such as the Health Utilities Index (HUI2; HUI3) and the RAND Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and its derivatives (SF-6D; SF-12;).

For convergent validity, moderate to strong agreement represented as significant correlation was generally found between EQ-5D Index and VAS scores and other generic HRQoL measures both at the domain and index level [21-23]. For discriminative validity, the EQ-5D was less able to detect clinical changes than other disease specific measures such as the KCCQ or NYHA and performed better when detecting large rather than small changes in disease severity [24]. There was also evidence of strong ceiling effects (i.e. inability to discriminate between comparatively good health states) across both domain and index values [21,25]. In general, the EQ-5D Index and VAS showed good reliability and responsiveness in comparison to other generic measures such as the SF-12 but were less responsive than disease-specific measures such as the KCCQ [26,27].

A wide range of mean and median EQ-5D scores were reported (Table 3 in Additional file 1). Studies of patients with ischaemic heart diseases (ICD codes I20-I25) reported mean index scores that ranged from 0.45 (SD 0.22) to 0.88 (no SD reported). Visual analogue scale (VAS) scores ranged from a mean of 45 (SD 17) to 82 (SD 13). Studies of heart failure (I50) patients reported mean index scores ranging from 0.31 (no SD) to 0.78 (0.11) and mean VAS scores from 37 (21) to 73 (18). Studies of cerebrovascular diseases (I60-I69) reported mean index scores ranging from 0.24 (0.39) to 0.90 (0.16) and mean VAS scores from 51 (SD 20) to 89 (no SD). Studies of peripheral vascular diseases (I73) reported mean index scores ranging from 0.33 (no SD) to 0.78 (0.23) and mean VAS scores ranging from 49 (no SD) to 71 (8).

The lowest mean EQ-5D index scores were reported in female patients with intermittent claudication undergoing secondary amputation [28]; patients with a large deterioration in heart failure [24]; and post-stroke patients [29] (Table 3 in Additional file 1). The highest mean EQ-5D index scores were reported in elderly CHD patients one year after undergoing exercise training [30]; post-trans-ischaemic attack (TIA) patients at four-year follow-up [31] and patients with history of subarachnoid haemorrhage [32].

An attempt was made to stratify mean EQ-5D index or VAS scores by disease severity (for example by CCS angina grading scale or NYHA heart failure classification). Both the CCS and NYHA scales range from class I (mild symptoms) to class IV (severe symptoms) and CCS can also be graded as 0 for no symptoms (Table 4 in Additional file 1). A previously published study stratified mean EQ-5D scores across CCS grades for patients with stable angina [33]. The results showed mean EQ-5D scores decreasing as the severity of angina increased. EQ-5D index scores ranged from 0.36 (95% CI: 0.25 to 0.48) for CCS grade IV to 0.81 (95% CI: 0.77 to 0.85) for CCS grade 0. Here, there was sufficient data available to stratify mean EQ-5D index scores by NYHA class in heart failure patients and by CCS class in patients with ischaemic heart disease (IHD). EQ-5D index scores were stratified into three categories of NYHA or CCS class based on the percentage of patients in a given group in a study in class III/IV (0-33%; 34-67%; 68-100%). It was assumed here that 0-33% in class III/IV corresponds to mild HF/angina whilst 68-100% corresponds to moderate/severe HF/angina.

In almost all cases, mean EQ-5D index scores increased with an increase in the proportion of patients with mild disease (Figure 2). Mean EQ-5D index scores decreased from 0.78 (SD 0.18) for mild states to 0.51 (SD 0.21) for moderate/severe health states. In common with heart failure patients, mean EQ-5D index scores for IHD patients generally decreased with the increasing proportions of patients with moderate/severe angina (Figure 3). Here, scores decreased from a mean of 0.80 (SD 0.05) for mild angina to 0.45 (SD 0.22) for moderate/severe angina.

An initial attempt was made to summarise the burden of CVD for each disease subgroup by calculating pooled means across studies. Both fixed and random effects meta-analyses were carried out for studies that used reported EQ-5D index scores and disease severity in terms of either CCS Angina class or NYHA heart failure class at baseline. Fixed and random effects meta-analyses of heart failure patients stratified by NYHA class and IHD patients stratified by CCS angina class produced I2 indices of between 82-96%, suggesting a high level of statistical heterogeneity between studies [34]. Such a degree of heterogeneity between studies ruled out any further estimation of pooled mean utility scores according to disease severity.

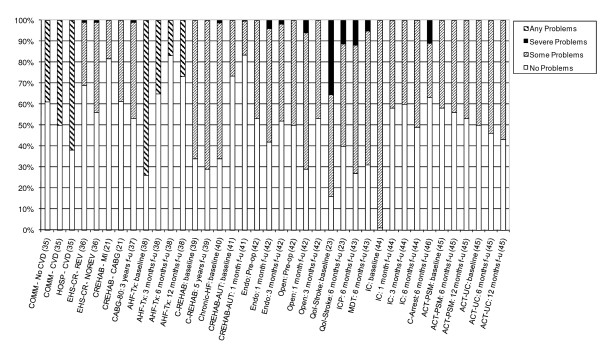

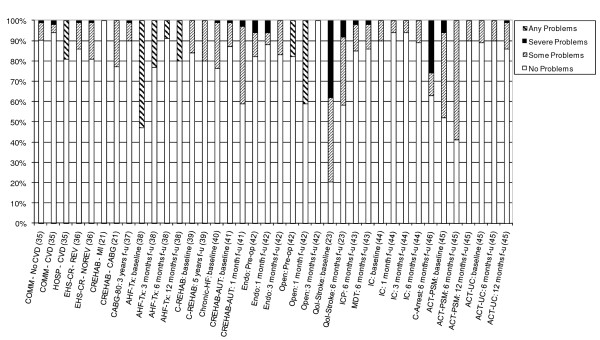

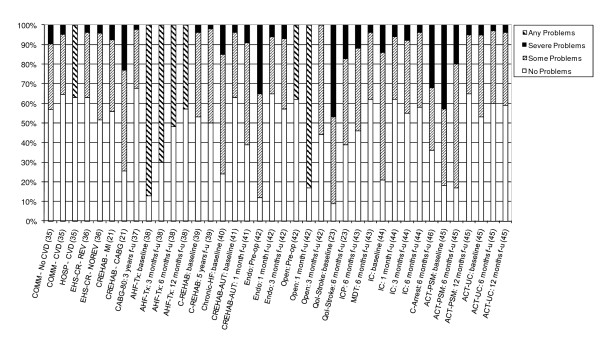

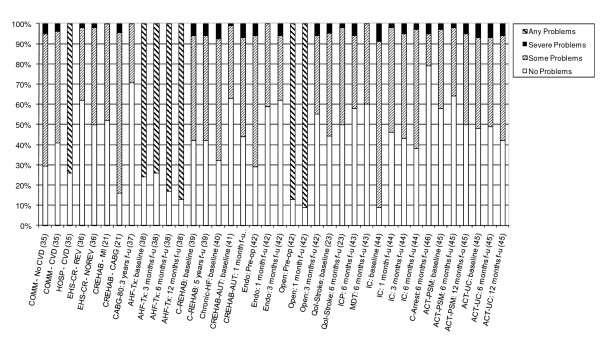

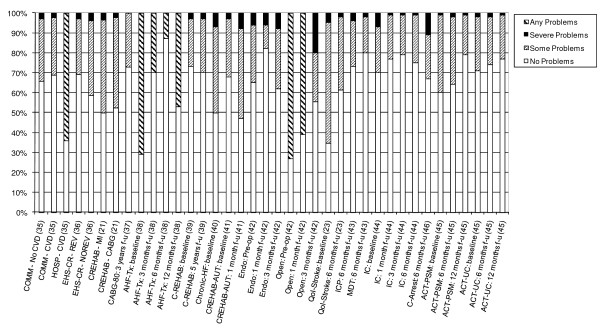

14 studies also provided detailed information on the dimension-specific burden of cardiovascular disease, exploring the distribution of scores across the five dimensions of the EQ-5D [21,23,35-46]. In examining the dimension-specific burden of disease among cardiovascular studies, the trend in the distribution of scores was fairly similar across all five dimensions. In general, problems with usual activities tended to be most common, followed by problems with mobility and pain/discomfort (Figures 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8).

Figure 4.

Distribution of Scores for Mobility Dimension of EQ-5D.

Figure 5.

Distribution of Scores for Self-Care Dimension of EQ-5D.

Figure 6.

Distribution of Scores for Usual Activities Dimension of EQ-5D.

Figure 7.

Distribution of Scores for Pain/Discomfort Dimension of EQ-5D.

Figure 8.

Distribution of Scores for Anxiety/Depression Dimension of EQ-5D.

Discussion

In recent years use of the EQ-5D to measure patient HRQoL in published studies within the cardiovascular field has increased. This largely reflects the growing requirement, over time, of clinical trials to consider cost-effectiveness alongside the clinical effectiveness of new interventions. As the "gold standard" form of economic evaluation in many health care systems, cost-utility analyses (CUA) rely on generic measures such as the EQ-5D for the calculation of QALYs. Increased use of the EQ-5D may also support the view that patient reported outcomes and quality of life are becoming more widely accepted as routine measures in clinical studies, with the EQ-5D being an internationally recognised generic measure of HRQoL. This summary of EQ-5D index and VAS scores in the cardiovascular field complements other published reports describing the use of the EQ-5D in the cancer and asthma/COPD literature and of utility scores associated with various conditions [47-50].

The review found that the majority of studies that included the EQ-5D were within IHD (I20 - I25) and cerebrovascular disease (I60 - I69), subgroups, reflecting the relative prevalence of these diseases worldwide. Stratification by disease severity (measured by CCS angina or NYHA heart failure scales) was possible for IHD patients and heart failure patients and illustrated a positive relationship with the EQ-5D when moving from severe to mild disease severity (Figures 2 and 3). However, calculation of pooled means across studies using meta-analytic techniques was not appropriate, given the high level of heterogeneity in terms of study design and patient characteristics. In general, evaluations of the validity and reliability of the EQ-5D suggested fairly strong convergent validity when assessed by correlations with other HRQoL measures and good discriminative abilities in detecting patients whose health status changed by a given clinical magnitude. However, there was evidence of strong ceiling effects across each domain for the index values. In terms of the dimension-specific burden of cardiovascular disease, problems with pain or discomfort were the most common, followed by problems with usual activities and mobility.

There was much heterogeneity in the scores observed across the studies, which was not necessarily entirely explained by the range of cardiovascular subgroups. The diverse range of index and VAS scores was also related to stage of illness or treatment (for example baseline versus post-treatment measurements) as well as non-disease-related factors such as other co-morbidities and demographic characteristics. Furthermore, no a priori quality criteria were imposed on studies included for review in terms of sample size or methodological quality which may explain some of the heterogeneity. On the other hand, imposing stringent inclusion criteria in terms of study methodological quality would have reduced the potential availability of studies considered for analysis. It is difficult to predict to what extent the level of heterogeneity would have been reduced if more stringent inclusion criteria had been imposed for the literature review.

Overall, this study illustrated the difficulty in attempting to adequately deal with statistical heterogeneity based on aggregated data from published studies [51]. This would suggest that individual patient-level data is required in order to estimate mean utility scores according to disease stage, at least within the cardiovascular field. Furthermore, not all studies used the same algorithm to calculate index-based scores with a third of studies also failing to report which scoring system was used. The choice of algorithm used to convert self-classification scores can affect the index-based score, as shown in a recent study which compared UK and US scoring algorithms in patients undergoing percuatenous coronary intervention (PCI) [52]. However, whilst country-specific societal preferences may reduce the scope for comparing HRQoL estimates across studies from different countries, they are more helpful to local decision making, especially when allocating resources within national health care programmes.

Conclusion

HRQoL measures such as the EQ-5D can be useful tools to clinicians in terms of evaluating the impact of cardiovascular disease on patients and can help to inform decision making and resource allocation. The use of the EQ-5D in CVD studies has increased in recent years and published studies provide evidence of its validity and reliability. The variation in EQ-5D index and VAS scores reported here largely reflect systematic differences in terms of disease stage, treatment and patient characteristics. In the future, as more studies of CVD present EQ-5D scores according to disease severity, it may be possible to calculate pooled mean estimates that can be useful in modelling of CVD-related health outcomes in economic evaluations.

Abbreviations used in Tables/Figures

AAA: Abdominal aortic aneurysm; ACS: Acute coronary syndromes; ACT: Anticoagulation therapy; AF: Atrial fibrillation; AH-Drug: Anti-hypertensive drug therapy; AHF: Advanced heart failure; AMI: Acute myocardial infarction; Amp.: Amputation; Angio: Coronary Angiography; ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiologists; ASCOT-AHD: Anglo-Scandinavian cardiac outcomes trial - anti-hypertensive drug treatment; Asym./Sym.: Asymptomatic/Symptomatic; AUT: Austria; AVR: Aortic valve replacement; BI: Barthel Index; BOTH-CABG/PCI/MM: Patients who are suitable for both CABG and PCI and receive CABG/PCI/MM; CABG: Coronary artery bypass graft; CABG-80: Coronary artery bypass surgery in octogenarians; CABG-CABG/PCI/MM: Patients who are suitable for CABG and receive CABG/PCI/MM; CABG-CPB: CABG using heart lung machine; CAD: Coronary artery disease; C-Arrest: Cardiac arrest; CCR: Comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation; CCS: Canadian Cardiovascular Society; CCU: Coronary care unit; CES-D: Centre for Epidemiological Studies - Depression Scale; CHD: Coronary heart disease; CHD-PHARM/Control: Community pharmacy-led medicines management programme/control treatment for patients with CHD; CML: Case method learning supported lipid-lowering strategy; COMM - CVD/NOCVD: Community dwelling-based elderly patients with/without CVD; CR: Cardiac resynchronisation; CR-Home/Hosp: Home/Hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation; C-REHAB: Cardiac rehabilitation; CS: Conservative strategy; CVA: Cerebrovascular Accident; CVD: Cardiovascular disease; Duplex US: Duplex ultrasonography; Echo: Echocardiography; EHS-CR: Euro Heart Survey on coronary revascularisation; Endo: Endovascular AAA surgery; ES: Effect size; Exercise-Qol: Long-term effects of exercise training on quality of life; F-u: Follow-up; GRS: Guyatt's responsiveness statistic; HeartMed: Lifestyle advice intervention by community pharmacists for heart failure patients; HF: Heart failure; HOSP - CVD: Hospital-based elderly patients with CVD; HRQoL: Health-related quality of life; HUI2/3: Health Utilities Index mark 2/3; IC: Intermittent claudication; ICC: Intra-class correlation; ICD: Implantable cardioverter defibrillator; ICP: Integrated care pathway; IHD: Ischaemic heart disease; IQR: Inter-quartile range; IS: Interventional strategy; IV: Intravenous; KCCQ: Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; LV: Left ventricular; MacNew: MacNew Heart Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire; MCS: Mental component summary; MDT: Multi-disciplinary team; MEDMAN: Community pharmacy-led medicines management services; MEPS: Medical expenditure panel survey; MI: Myocardial infarction; MI - Self-help: Home-based self-help rehabilitation package for MI patients; MIDCAB: Minimally invasive direct CABG; MM: Medical management; MR Angio: Magnetic resonance angiography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; MT: Medical therapy; MVPS: Mitral valve prolapse syndrome; NYHA: New York Heart Association; OP-CABG: Off-pump CABG; Open: Open AAA surgery; PAOD: Peripheral arterial occlusive disease; PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; PCI-BMS: PCI with bare-metal stents; PCI-CABG/MM/PCI: Patients who are suitable for PCI and receive CABG/PCI/MM; PCI-DES: PCI with drug-eluting stents; PCS: Physical component summary; PER: Peripheral endovascular revascularisation; Pre-op: Pre-operation; Proxy: HRQol questionnaire completed by spouse/family member; PSM: Patient self-management; P-PTCA: Primary PTCA; P-Stent: Primary stent placement; PTCA: Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; QLMI: Quality of Life after MI questionnaire; QoL: Quality of life; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; REV/NO REV: Eligible/Ineligible for Revascularisation; SAH: Subarachnoid haemorrhage; SCOPE-Drug/Control: Study on cognition and prognosis in the elderly - Drug/Control treatment; SD: Standard deviation; SES: Socioeconomic status; SF-36: Short-form 36-item health survey questionnaire; SF-6D: Short-form 6D; SF-12: Short-form 12-item health survey questionnaire; SPECT: Single photon emission computed tomography; SRM: Standardised response means; Stroke-4Y: Four years post-stroke; TIA: Trans-ischaemic attack; Trans.: Heart Transplantation; Tx: Treatment; UC: Usual care; VAD: Ventricular assist device; VAS: Visual analogue scale; VascuQol: Vascular Quality of Life Questionnaire; -ve/+ve: Deterioration/Improvement in condition; WHO-ICD: World Health Organisation - International Classification of Diseases; W-list: Waiting-list.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MD participated in the design of the study, carried out the systematic literature review, conducted any data analysis and drafted the manuscript. KG provided support in the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. LS participated in the design of the study, provided support in the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. MB conceived of the study, participated in the design of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Tables. Table 1: Description of studies that have used the EQ-5D as an outcome measure in clinical and observational studies of patients with cardiovascular disease. Table 2: Summary of studies examining validity and reliability of EQ-5D in cardiovascular disease (n = 10). Table 3: Summary of EQ-5D utility scores reported in cardiovascular studies. Table 4: Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) and New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification systems [53-95].

Contributor Information

Matthew TD Dyer, Email: mdyer@cru.rcpsych.ac.uk.

Kimberley A Goldsmith, Email: kimberley.goldsmith@kcl.ac.uk.

Linda S Sharples, Email: linda.sharples@mrc-bsu.cam.ac.uk.

Martin J Buxton, Email: martin.buxton@brunel.ac.uk.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the funding support of the EuroQol Group (PI: Buxton). An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2008 EuroQol Plenary Meeting, Baveno, Italy, Sept 11-13, 2008. The authors thank Simon Pickard for helpful comments on an earlier version of the paper. MD is now employed at the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health within the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). However, the study was conducted whilst he was a researcher at Brunel University.

References

- World Health Organisation. The World Health Report 2003: Shaping the Future. Geneva. 2003.

- Leal J, Luengo-Fernandez R, Gray A, Petersen S, Rayner M. Economic burden of cardiovascular diseases in the enlarged European Union. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1610–1619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson JR, Clinch JJ. Assessment of quality of life in patients with cardiac disease - the role of psychosomatic medicine. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48:405–415. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(99)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Criteria Committee of the New York Heart Association. Nomenclature and Criteria for Diagnosis of Diseases of the Heart and Great Vessels. 9. Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown & Co; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Campeau L. The Canadian Cardiovascular Society grading of angina pectoris revisited 30 years later. Can J Cardiol. 2002;18:439–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spertus JA, Winder JA, Dewhurst TA, Deyo RA, Prodzinski J, McDonell M, Fihn SD. Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: a new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:333–341. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer S, Lim L, Guyatt G, Oldridge N. The MacNew Heart Disease health-related quality of life instrument: A summary. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt G. Measurement of health related quality of life in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22(Suppl A):185A–191A. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90488-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ. 2002;21:271–292. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(01)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong WJ, Feeny DH, Torrance GW, Barr RD. The Health Utilities Index (HUI) system for assessing health-related quality of life in clinical studies. Ann Med. 2001;33:375–384. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33:337–343. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan PD. Modelling Valuations for EuroQol Health States. Med Care. 1997;35(11):1095–1108. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199711000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dankova I, Dlouhy M. The measurement of health status with Czech version of European quality of life questionnaire: version EQ-5D. Czech Health Policy Econ. 2001. p. 2.

- Wittrup-Jensen K, Lauridsen J, Gudex C, Brooks R, Pedersen K. Estimating Danish EQ-5D tariffs using the time trade-off (TTO) and visual analogue scale (VAS) methods. Lund: Swedish Institute for Health Economics; pp. 257–292. [Google Scholar]

- Lamers L, Stalmeier P, Krabbe P, Busschbach J. The Dutch tariff: results and arguments for an effective design for national EQ-5D valuation studies. Health Econ. 2006;15:1121–1132. doi: 10.1002/hec.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claes C, Greiner W, Uber A, Schulenberg J-M. The new German version of the EuroQol quality of life questionnaire. Centre for Health Policy and Law, Erasmus University Rotterdam; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw JWP, Johnson JAP, Coons SJP. US Valuation of the EQ-5D Health States: Development and Testing of the D1 Valuation Model. Med Care. 2005;43:203–220. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner W, Weijnen T, Nieuwenhuizen M, Oppe S, Badia X, Busschbach J, Buxton M, Dolan P, Krabbe P, Ohinmaa A, Parkin D, Roset M, Sintonen H, Tsuchiya A, Charro F. A single European currency for EQ-5D health states. Eur J Health Econ. 2003;4:222–231. doi: 10.1007/s10198-003-0182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. Geneva. 2007.

- Higgins J, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweikert B, Hahmann H, Leidl R. Validation of the EuroQol questionnaire in cardiac rehabilitation. Heart. 2006;92:62–67. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.052787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowels D, McGloin J, Westfall JM, Holcomb S. Validation of the EQ-5D quality of life instrument in patients after myocardial infarction. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:95–105. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0614-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard AS, Johnson JA, Feeny DH. Responsiveness of generic health-related quality of life measures in stroke. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:207–219. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-3928-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spertus J, Peterson E, Conard M, Heidenreich P, Rumholz M, Jones P, McCullogh PA, Pina I, Wooley J, Weintraub WS, Rumsfeld JS. Monitoring clinical changes in patients with heart failure: A comparison of methods. Am Heart J. 2005;150:707–715. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Stel H, Buskens E. Comparison of the SF-6D and the EQ-5D in patients with coronary heart disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:20. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eurich D, Johnson J, Reid K, Spertus J. Assessing responsiveness of generic and specific health related quality of life measures in heart failure. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:89. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman P, Slattery J, Farrell B, Dennis M, Sandercock P. Qualitative Comparison of the Reliability of Health Status Assessments With the EuroQol and SF-36 Questionnaires After Stroke. Stroke. 1998;29:63–68. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangelder MJD, McDonnel J, Van Busschbach JJ, Buskens E, Algra A, Lawson JA, Eikelboom BC. Quality of life after infrainguinal bypass grafting surgery. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 1999;29:913–919. doi: 10.1016/S0741-5214(99)70219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard AS, Johnson JA, Feeny DH, Shuaib A, Carriere KC, Nasser AM. Agreement Between Patient and Proxy Assessments of Health-Related Quality of Life After Stroke Using the EQ-5D and Health Utilities Index. Stroke. 2004;35:607–612. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000110984.91157.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hage C, Mattsson E, Stahle A. Long term effects of exercise training on physical activity level and quality of life in elderly coronary patients - A three- to six-year follow-up. Physiother Res Int. 2003;8:13–22. doi: 10.1002/pri.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haacke C, Althaus A, Spottke A, Siebert U, Back T, Dodel R. Long-Term Outcome After Stroke: Evaluating Health-Related Quality of Life Using Utility Measurements. Stroke. 2006;37:193–198. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000196990.69412.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf IC van der, Wermer MJH, Velthuis BK, Buskens E, Bossuyt PMM, Rinkel GJE. Psychosocial impact of finding small aneurysms that are left untreated in patients previously operated on for ruptured aneurysms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:748–752. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.079194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longworth L, Buxton M, Sculpher M, Smith D. Estimating utility data from clinical indicators for patients with stable angina. Eur J Health Econ. 2005;6:347–353. doi: 10.1007/s10198-005-0309-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowiak E, Kostka T. Influence of chronic cardiovascular disease and hospitalisation due to this disease on quality of life of community-dwelling elderly. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:1281–1289. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen M, Scholte op Reimer W, Norkvel TM, De Geest S, Fridlund B, Heikkila J, Jaarsma T, Mortensson J, Moons P, Smith K, Stewart S, Stromberg A, Thompson DR, Wijns W. Pharmacological treatment and perceived health status during 1-year follow up in patients diagnosed with coronary artery disease, but ineligible for revascularization: Results from the Euro Heart Survey on Coronary Revascularization. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006;5:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollano JA, Rose EA, Williams DL, Thornton BM, Quint ER, Apfelbaum MM, Wasserman HM, Cannavale GA, Smith CR, Reemstma KM, Greene RJ. Cost-Effectiveness of Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery in Octogenarians. Annals of Surgery September. 1998;228(3):297–306. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almenar-Pertejo M, Almenar L, Martinez-Dolz L, Campos J, Galan J, Girones P, Ortega F, Ortega T, Rebollo P, Salvador A. Study on Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Advanced Heart Failure Before and After Transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:2524–2526. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin J, Williams WR, Ross L, Hutchison S. Five-year follow-up findings from a randomized controlled trial of cardiac rehabilitation for heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15:162–167. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282f10e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert MJ, Freemantle N, Cleland JGF. The impact of chronic heart failure on health-related quality of life data acquired in the baseline phase of the CARE-HF study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer S, Kullich W, Graninger U, Brandt D, Gassner A, Klicpera M, Laimer H, Marko C, Schwann H, Moller R. Cardiac rehabilitation in Austria: short term quality of life improvements in patients with heart disease. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2006;118:744–753. doi: 10.1007/s00508-006-0727-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lottman PEM, Laheij RJF, Cuypers PWM, Bender M, Buth J. Health-related quality of life outcomes following elective open or endovascular AAA Repair: A randomised controlled trial. J Endovasc Surg. 2004;11:323–329. doi: 10.1583/03-1141.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulch D, Melbourn A, Perez I, Kalra L. Integrated Care Pathways and Quality of Life on a Stroke Rehabilitation Unit. Stroke. 2002;33:1600–1604. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000017144.04043.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch J, Hunink M. Comparison of the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI3) and the EuroQol EQ-5D in patients treated for intermittent claudication. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:591–601. doi: 10.1023/A:1008929129537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jowett S, Bryan S, Murray E, McCahon D, Raftery J, Hobbs F, Fitzmaurice D. Patient self-management of anticoagulation therapy: a trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:632–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granja C, Cabral G, Pinto A, Costa-Pereira A. Quality of life 6-months after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2002;55:37–44. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9572(02)00203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard AS, Wilke CT, Lin HW, Lloyd A. Health Utilities Using the EQ-5D in Studies of Cancer. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25:365–384. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200725050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard AS, Wilke C, Jung E, Patel S, Stavem K, Lee TA. Use of a preference-based measure of health (EQ-5D) in COPD and asthma. Respir Med. 2008;102:519–536. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PW, Lawrence WF, Ghushchyan VM. A National Catalog of Preference-Based Scores for Chronic Conditions in the United States. Med Care. 2005;43:736–749. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000172050.67085.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tengs TO, Wallace AM. One Thousand Health-Related Quality-of-Life Estimates. Med Care. 2000;38:583–637. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200006000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J, Thompson S, Deeks J, Altman D. Statistical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of clinical trials: a critical appraisal of guidelines and practice. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7:51–61. doi: 10.1258/1355819021927674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrive FM, Ghali WA, Johnson JA, Donaldson CP, Manns BJ. Use of the U.S. and U.K. Scoring Algorithm for the EuroQol-5D in an Economic Evaluation of Cardiac Care. Med Care. 2007;45:269–273. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250480.55578.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascione R, Reeves BC, Taylor FC, Seehra HK, Angelini GD. Beating heart against cardioplegic arrest studies (BHACAS 1 and 2): quality of life at mid-term follow-up in two randomised controlled trials. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:765–770. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca HPB-L, Kaiser C, Bernheim A, Zellweger MJ, Jeger R, Buser PT, Osswald S, Pfisterer M. Cost-effectiveness of drug-eluting stents in patients at high or low risk of major cardiac events in the Basel Stent KostenEffektivitats Trial (BASKET): an 18-month analysis. Lancet. 2007;370:1552–1559. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61660-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denvir MA, Lee AJ, Rysdale J, Walker A, Eteiba H, Starkey IR, Pell JP. Influence of socioeconomic status on clinical outcomes and quality of life after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:1085–1088. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.044255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning J, Waller JRL, Smith B, Pitts S, Kendall SWH, Khan K. Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting is Associated With Excellent Long-Term Survival and Quality of Life: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:1988–1993. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eefting F, Nathoe H, van Dijk D, Jansen E, Lahpor J, Stella P, Suyker W, Diephuis J, Suryapranda H, Ernst S, Borst C, Buskens E, Grobbee D, de Jaegere P. Randomized Comparison Between Stenting and Off-Pump Bypass Surgery in Patients Referred for Angioplasty. Circulation. 2003;108:2870–2876. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000100723.50363.2C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin SC, Barber JA, Manca A, Sculpher MJ, Thompson SG, Buxton MJ, Hemingway H. Cost effectiveness of clinically appropriate decisions on alternative treatments for angina pectoris: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2007;334:624–628. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39129.442164.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiessling A, Zethraeus N, Henriksson P. Cost of lipid lowering in patients with coronary artery disease by Case Method Learning. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21:180–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Henderson RA, Pocock SJ, Clayton T, Sculpher MJ, Fox KAA. Health-related quality of life after interventional or conservative strategy in patients with unstable angina or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: One-year results of the third randomized intervention trial of unstable angina (RITA-3) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse M, Hochstrasser S, Zwisler AD, Kjellberg J. Comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation: A cost assessment based on a randomized clinical trial. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2006;22:478–483. doi: 10.1017/S0266462306051403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey EA, Musgrave RJ, Freeman JV, Tod AM, Scott P. Psychological morbidity after myocardial infarction in an area of deprivation in the UK: evaluation of a self-help package. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;3:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legrand VMG, Serruys PW, Unger F, van Hout BA, Vrolix MCM, Fransen GMP, Nielsen TT, Paulsen PK, Gomes RS, de Queiroz de Melo J, Marques dos Santos Neves J, Lindeboom W, Backx B. Three-Year Outcome After Coronary Stenting Versus Bypass Surgery for the Treatment of Multivessel Disease. Circulation. 2004;109:1114–1120. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118504.61212.4B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Project Evaluation Team. The MEDMAN study: a randomized controlled trial of community pharmacy-led medicines management for patients with coronary heart disease. Fam Pract. 2007;24:189–200. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cml075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puskas JD, Williams WH, Mahoney EM, Huber PR, Block PC, Duke PG, Staples JR, Glas KE, Marshall JJ, Leimbach ME, McCall SA, Petersen RJ, Bailey DE, Weintraub WS, Guyton RA. Off-Pump vs Conventional Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: Early and 1-Year Graft Patency, Cost, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes: A Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1841–1849. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.15.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves BC, Angelini GD, Bryan AJ, Taylor FC, Cripps T, Spyt TJ, Samani NJ, Roberts JA, Jacklin P, Seehra HK, Culliford LA, Keenan DJM, Rowlands DJ, Clarke B, Stanbridge R, Foale R. A multi-centre randomised controlled trial of minimally invasive direct coronary bypass grafting versus percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty with stenting for proximal stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. NCCHTA Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:1–56. doi: 10.3310/hta8160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharples L, Hughes V, Crean A, Dyer M, Buxton M, Goldsmith K, Stone D. Cost-effectiveness of functional cardiac testing in the diagnosis and management of coronary artery disease: a randomised controlled trial. The CECaT trial. 11(49) NCCHTA Health Technol Assess. 2007;11:1–136. doi: 10.3310/hta11490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrive FM, Manns BJ, Galbraith PD, Knudtson ML, Ghali WA. for The APPROACH Investigators. Economic evaluation of sirolimus-eluting stents. CMAJ. 2005;172:345–351. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RS, Watt A, Dalal HM, Evans PH, Campbell JL, Read KLQ, Mourant AJ, Wingham J, Thompson DR, Pereira Gray DJ. Home-based cardiac rehabilitation versus hospital-based rehabilitation: A cost effectiveness analysis. Int J of Cardiol. 2007;119:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.07.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Wu EQ, Zheng ZJ, Sullivan PW, Zhan L, Labarthe DR. Patient-Reported Health Status in Coronary Heart Disease in the United States: Age, Sex, Racial, and Ethnic Differences. Circulation. 2008;118:491–497. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.752006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland JGF, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, Tavazzi L. The Effect of Cardiac Resynchronization on Morbidity and Mortality in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1539–1549. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland R, Brooksby I, Lenaghan E, Ashton K, Hay L, Smith R, Shepstone L, Lipp A, Daly C, Howe A, Hall R, Harvey I. Effectiveness of visits from community pharmacists for patients with heart failure: HeartMed randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2000;334:1098. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39164.568183.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharples L, Buxton M, Caine N, Cafferty F, Demiris N, Dyer M, Freeman C. Evaluation of the ventricular assist device programme in the UK. NCCHTA Health Technol Assess. 2006;10:1–138. doi: 10.3310/hta10480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer CA, Norman PE, Jamrozik K, Tuohy R, Lawrence-Brown M. Is screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm bad for your health and well-being? ANZ J Surg. 2004;74(12):1069–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.03270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton M, Caine N, Chase D, Connelly D, Grace A, Jackson C, Parkes J, Sharples L. A review of the evidence on the effects and costs of implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy in different patient groups, and modelling of cost-effectiveness and cost-utility for these groups in a UK context. NCCHTA Health Technol Assess. 2006;10:1–132. doi: 10.3310/hta10270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeneveld P, Matta M, Suh J, Yang F, Shea J. Quality of Life Among Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Recipients in the Primary Prevention Therapeutic Era. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30:463–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2007.00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eck JW, van Hemel NM, van den Bos A, Taks W, Grobbee DE, Moons KG. Predictors of improved quality of life 1 year after pacemaker implantation. Am Heart J. 2008;156:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, White AR, James MA, Hemsley AG, Johnson P, Chambers J, Ernst E. Acupuncture for Subacute Stroke Rehabilitation: A Sham-Controlled, Subject- and Assessor-Blind, Randomized Trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2026–2031. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.17.2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T, Enderby P, Rigby AS. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate intensity of community-based rehabilitation provision following stroke or hip fracture in old age. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20:123–131. doi: 10.1191/0269215506cr933oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Wu EQ, Zheng ZJ, Croft JB, Greenlund KJ, Mensah GA, Labarthe DR. Impact of Stroke on Health-Related Qualityof Life in the Noninstitutionalized Population in the United States. Stroke. 2006;37:2567–2572. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000240506.34616.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti AD, Elmfeldt D, Hansson L, Breteler M, James O, Lithell H, Olofsson B, Skoog I, Tenkwalder P, Zanchetti A, Wiklund I. Cognitive Function and Health-Related Quality of Life in Elderly Patients with Hypertension - Baseline Data from the Study on COgnition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE) Vol. 11. Blood Press; 2002. pp. 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krijnen P, van Jaarsveld BC, Hunink MGM, Habbema JDF. The effect of treatment on health-related quality of life in patients with hypertension and renal artery stenosis. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:467–470. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren P, Kahan T, Poulter N, Buxton M, Svarvar P, Dahloff B, Jonsson B. Utility loss and indirect costs following cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients: the ASCOT health economic substudy. Eur J Health Econ. 2007;8:25–30. doi: 10.1007/s10198-006-0002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook TA, Galland RB. Quality of life changes after angioplasty for claudication: medium-term results affected by comorbid conditions. Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;5:424–426. doi: 10.1016/S0967-2109(97)00037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries M, Ouwendijk R, Flobbe K, Nelemans PJ, Kessels AG, Schurink GH, Vliet JA van der, Heijstraten FMJ, Cuypers JWM, Duijm LEM, van Engelshoven JMA, Hunink MGM, de Haan MW. Peripheral Arterial Disease: Clinical and Cost Comparisons between Duplex US and Contrast-enhanced MR Angiography--A Multicenter Randomized Trial. Radiology. 2006;240:401–410. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2402050223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safley DM, House JA, Laster SB, Daniel WC, Spertus JA, Marso SP. Quantifying Improvement in Symptoms, Functioning, and Quality of Life After Peripheral Endovascular Revascularization. Circulation. 2007;115:569–575. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.643346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovacek L, Slovackova B, Chovanec V. The effect of femoral and popliteal percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty on patients' quality of life. Sao Paulo Med J. 2007;125:250–252. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802007000400012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch JL, Graaf Y van der, Hunink MGM. Health-Related Quality of Life After Angioplasty and Stent Placement in Patients With Iliac Artery Occlusive Disease: Results of a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Circulation. 1999;99:3155–3160. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.24.3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstrom K, Johannesson M, Diderichsen F. Swedish population health-related quality of life results using the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:621–635. doi: 10.1023/A:1013171831202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung HF, Kao PF, Lin YS, Chen FC, Tsai JC, Chan P. Changes of Serum b-Endorphin by Programmed Exercise Training Are Correlated with Improvement of Clinical Symptoms and Quality of Life in Female Mitral Valve Prolapse Syndrome. Cardiology. 2007;108:252–257. doi: 10.1159/000096952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maliwa MA, Heijden GJMG van der, Bots ML, van Hout BA, Casselman FP, van Swieten H, Vermeulen FEE. Quality of life and NYHA class 30 years after mechanical aortic valve replacement. Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;11:381–387. doi: 10.1016/S0967-2109(03)00030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiraki C, Kaitelidou D, Papakonstantinou V, Prezerakos P, Maniadakis N. Health-related quality of life measurement in patients with coronary heart disease and heart failure to a cardiology department of a secondary urban hospital in Greece. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2008;49:241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Exel NJA, Scholte op Reimer WJM, Koopmanschap MA. Assessment of post-stroke quality of life in cost-effectiveness studies: The usefulness of the Barthel Index and the EuroQoL-5D. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:427–433. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018496.02968.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries M, Ouwendijk R, Kessels AG, de Haan MW, Flobbe K, Hunink MGM, van Engelshoven JMA, Nelemans PJ. Comparison of generic and disease-specific questionnaires for the assessment of quality of life in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busschbach JJV, McDonnell JM, Tangelder MJD, Eikelboom BCM, Buskens EM, Algra AM, Lawson JEM. EuroQol values for economic modelling quality of life after infrainguinal bypass grafting surgery: a rectification. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30:1162–1163. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables. Table 1: Description of studies that have used the EQ-5D as an outcome measure in clinical and observational studies of patients with cardiovascular disease. Table 2: Summary of studies examining validity and reliability of EQ-5D in cardiovascular disease (n = 10). Table 3: Summary of EQ-5D utility scores reported in cardiovascular studies. Table 4: Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) and New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification systems [53-95].