Abstract

Serum concentrations of lipoprotein mass by flotation rate were measured in 12 long-distance runners and 64 sedentary men by analytic ultracentrifugation. The runners had significantly lower serum mass concentrations of the smaller, denser low-density lipoprotein particles of flotation rates Sf0-7 (including the LDL-II, LDL-III, and LDL-IV subspecies), very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles of Sf 20-400, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles of flotation rates F1.20 0-1.5 (predominately the HDL3 subspecies), and higher serum mass concentrations of HDL particles with flotation rates between F1.20 2.0-9.0 (including HDL2a and HDL2b and less dense particles belonging to HDL3) than did sedentary men. Lipoprotein lipase activity was higher, and hepatic lipase activity was lower in runners than in the sedentary men. Thus, the effects of endurance exercise training to lower LDL may be specific to the smaller, denser LDL particle region. Similarities in the lipoprotein mass profiles of the runners and the low-risk profiles of sedentary, middle-aged women suggest the effects of common metabolic factors possibly leading to reduced risk of coronary artery disease.

Long-distance running and other endurance activities are reported to elevate plasma concentrations of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and to decrease plasma concentrations of low-density (LDL) and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol in men and women [1–7]. Previous studies of lipoproteins in relation to exercise have focused primarily on the measurements of the total cholesterol and various protein components of the HDL, LDL, and VLDL particles. These variables may not adequately portray the relationship of endurance exercise training to lipoprotein concentrations since there is much evidence to suggest that multiple subspecies of lipoprotein particles exist for these three lipoprotein species [8–12]. The technique of analytic ultracentrifugation may be used to estimate the serum mass concentrations of lipoprotein subspecies, and to measure directly the mass concentrations of finer subdivisions of very-low-density (14 intervals), intermediate-density (4 intervals), low-density (11 intervals), and high-density lipoproteins (15 intervals) by particle flotation rate. Differences in the serum lipoprotein mass concentrations of runners and sedentary men have not been previously reported for LDL and HDL subspecies, nor for individual flotation intervals within HDL, LDL, and VLDL particle regions.

LIPOPROTEIN HETEROGENEITY

The traditional measurement LDL-cholesterol is a composite measurement that includes the cholesterol content of both the LDL (Sf 0-12) and intermediate density lipoprotein (IDL, Sf 12-20) particles. Further heterogeneity within the LDL particle region (Sf 0-l2) is evident from the presence of distinct isopycnic banding regions when LDL is subjected to density gradient ultracentrifugation, from the multiple bands that appear for gradient polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of LDL, and from correlational analyses of the relationships of peak flotation rates from analytic ultracentrifugation [8–10]. At least four major subspecies of LDL particles exist within the flotation interval of Sf 0-l2 as assessed by the analytic ultracentrifuge: LDL-I (approximately Sf 7.5-10.5), LDL-II (Sf 5.7-7.5), LDL-III (Sf 4.1-5.7), and LDL-IV (Sf 0-4.1) [8,9].

Two major HDL subspecies are recognized: a more-dense HDL3 subspecies and a less-dense HDL2 subspecies. Serum concentrations of HDL3 are most frequently approximated from analytic ultracentrifugation as the total lipoprotein mass for flotation (F) rates between F1.20 0-3.5 and those of HDL2 as the total mass for F1.20 3.5-9.0 [9], or alternatively, by a computer algorithm that fits separate distributions to estimate HDL2a, and HDL2b, and HDL3 particle distributions [10,11]. Their partial separation is also achieved by preparative centrifugation, density gradient ultracentrifugation, gradient polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and zonal ultracentrifugation [13].

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE RISK

Much evidence suggests that high-, low-, intermediate-, and very-low-density lipoproteins and their subspecies have different relationships to coronary heart disease (CHD). High serum concentrations of the total cholesterol [14], total apolipoprotein (apo) A-1 [15], and the total lipoprotein mass [16] of HDL particles appear to provide protection against CHD. Low concentrations of either the HDL2, HDL3, or both the HDL2 and HDL3 subspecies of HDL are associated with increased CHD risk and severity. Two studies have compared the level of coronary disease with HDL subspecies in cross-sectional samples of men who received coronary arteriography: Miller et al [17] found the degree of coronary stenosis to correlate inversely with HDL2-cholesterol concentrations but not with HDL3-cholesterol concentrations in plasma, and Levy et al [18] reported that the number of severely diseased coronary arteries correlated inversely with serum concentrations of HDL3-mass but not with HDL2-mass as measured by analytic ultracentrifugation. Ballantyne et al [19] reported that survivors of myocardial infarctions had less HDL-total mass, HDL2-cholesterol, HDL2-phospholipid, HDL2-protein, and HDL2-apo A-I than did apparently healthy case-control subjects. The only prospective study to measure both HDL2 and HDL3 that we are aware of found that low serum concentrations of both were significantly predictive of future CHD [16].

The association between CHD and LDL-cholesterol is well established [20], but less is known about the relationship of CHD to lipoprotein subfractions within the low to very-low-density regions. High serum concentrations of total LDL-mass (Sf 0-l 2) were reported to correlate with the number of severely diseased coronary arteries [18] and to predict myocardial infarctions prospectively in men [16], and VLDL-mass of both Sf20-100 and Sf100-400 predicted myocardial infarctions in the Framingham cohort [16]. Women have on the average less LDL-cholesterol, LDL-mass of Sf 0-7, less IDL-mass, and less VLDL-mass of Sf 20-400, and more HDL2-mass and LDL-mass of Sf7-12 than men [10]. Some or all of these lipoprotein differences may contribute to the lower CHD incidence in women vis-a-vis men.

To understand better the associations between lipoprotein concentrations and long-term exercise training, and the possible roles of hepatic and lipoprotein lipase activity levels in mediating these associations, this report compares the lipoprotein subfraction concentrations and lipase activity levels of 12 middle-aged long-distance male runners and 81 middle-aged sedentary men (designated as nonrunners in the text that follows) who volunteered to later participate in a one-year running program [5–7]. Results are also presented by individual flotation intervals to delineate the runner versus nonrunner lipoprotein differences to the finest resolution currently distinguished by analytic ultracentrifugation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample and Laboratory Procedures

The 12 long-distance runners were selected because of their participation in the sport for several years and their moderate or high activity level at the time of the survey (mean±SD: 64±35 km/wk). Nonrunners were neither currently on a program of regular exercise (defined as regular participation 3 or more times per week), nor employed in a strenuous job [5–7].

Blood from runners and nonrunners was collected after an overnight fast (12–l4 hours) and plasma cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and VLDL-cholesterol were measured by the methods of the Lipid Research Clinics [21]. Their serum lipoproteins were measured by analytic ultracentrifugation [22], and concentrations of total lipoprotein mass were estimated using computer techniques [8,9,22] for 15 HDL flotation intervals (half-integer increments between F1.200-6.0 and integer increments thereafter), 11 LDL flotation intervals between Sf 0-12 (integer increments between Sf 0-10 and then Sf 10-12), 4 IDL flotation intervals between Sf 12-20 (two unit increments), and 14 VLDL flotation intervals between Sf 20-400 (increments of ten units below Sf100 and increments of 50 units thereafter).

Postheparin lipoprotein lipase and hepatic lipase activities were determined for the 12 runners and 20 randomly selected nonrunners from blood samples collected in tubes containing 2 U heparin/mL whole blood, 10 minutes after rapid intravenous administration of 10 U/kg body weight of sodium heparin. Extrahepatic (ie, lipoprotein) lipase was distinguished from hepatic lipase by its selective inactivation by protamine sulfate [23].

Statistical Procedures

Serum lipoprotein concentrations and lipase activity levels of runners and nonrunners are summarized in terms of the means and standard deviations for the two groups. The modest sample size of the exercise group may increase the sensitivity of the analysis to extreme or outlier observations and suggests caution in the use of parametric techniques that postulate asymptotic normality. Therefore, the significance of the differences between the two groups are evaluated initially by the nonparametric Wilcoxon sign rank test (Similar results were obtained for the parametric t-test). Analysis of covariance is used to adjust the runner and nonrunner lipoprotein differences for effects due to adiposity.

RESULTS

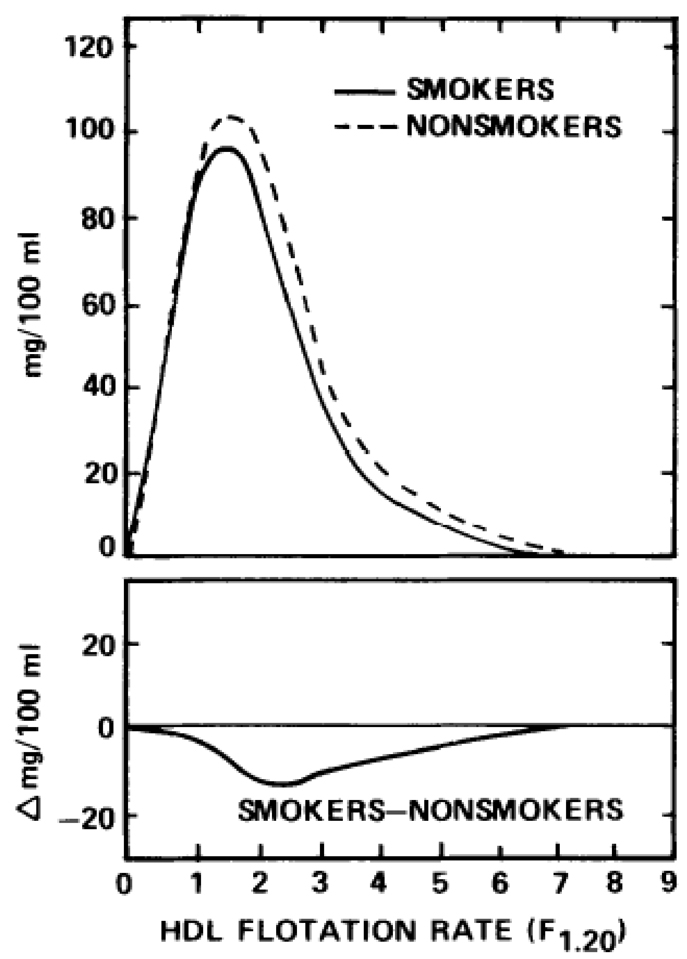

Although none of the runners smoked cigarettes, 17 of the 81 nonrunners were smokers who smoked an average of 14.9 cigarettes per day. These 17 sedentary smokers had significantly lower (P≤0.05) plasma HDL-cholesterol (mean±SD: 44.9±8.5 vs. 49.6 ± 8.7 mg/dL) and serum HDL-mass of both the predominately HDL2 density region of F1.20 3.5-9.0 (29.2 ± 31.0 vs. 42.7±31.0 mg/dL) and the predominately HDL3 density region of F1.20 0-3.5 (212.5±35.4 vs. 236.6±35.7 mg/dL) than the 64 sedentary men who did not smoke (Fig 1). Therefore, to eliminate the effects of cigarette smoking on the lipoprotein differences of the runners and nonrunners, we excluded the 17 smokers from the sample of sedentary men and compared the lipoprotein profiles of the 12 runners with the lipoprotein profiles of the remaining 64 nonrunners who did not smoke cigarettes (16 of whom received post heparin plasma lipase measurements) in all subsequent analyses.

Fig 1.

Upper panel displays the average distributions of serum high-density (HDL) lipoprotein mass concentration by flotation rate in sedentary male nonsmokers (N = 64) and sedentary male smokers (N = 17). The average HDL mass distributions for the nonsmokers and the smokers are computed by averaging the heights of the individual curves of the 64 nonsmokers and the 17 smokers, respectively, at each flotation rate. The HDL difference curve of the lower panel is computed by subtracting the average HDL-mass concentration of the nonsmokers from the average for the smokers.

Low-Density Lipoproteins

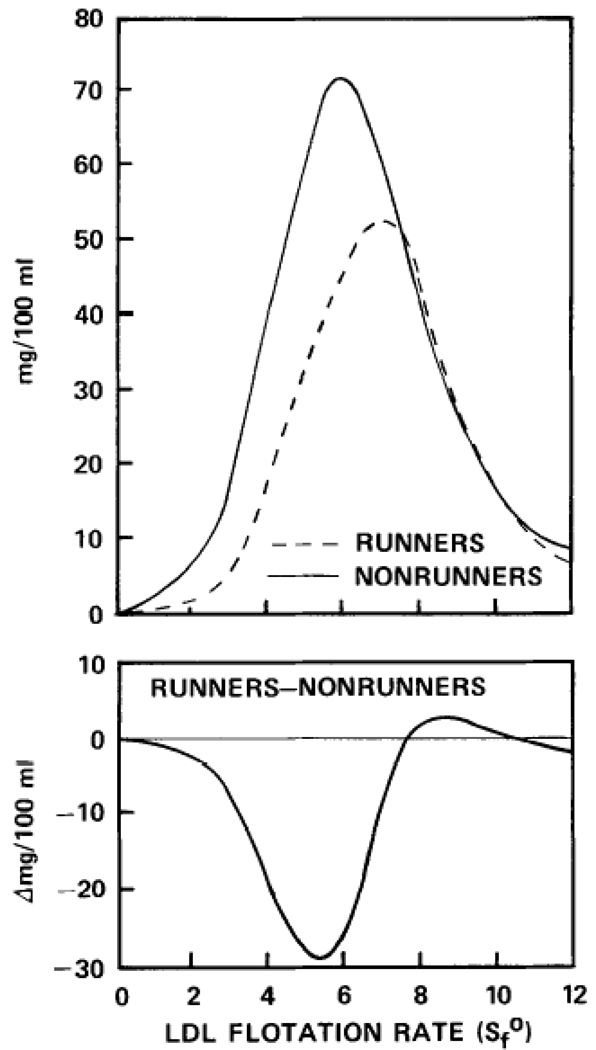

Table 1 shows that the runners had significantly lower concentrations of plasma total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol and serum lipoprotein mass of the smaller LDL particles of Sf 0-7 (including LDL-II, LDL-III, and LDL-IV) than the nonrunners, but that serum lipoprotein mass of Sf7-12 (predominantly LDL-I) was not significantly different between the two groups. LDL-mass concentrations of individual flotation intervals were significantly lower in runners than nonrunners for the five individual flotation intervals within Sf 2-7 (data not shown). Figure 2, which compares the average distribution of the LDL particles by flotation rate for the runners and nonrunners, shows that the lower concentrations of the slower floating, smaller LDL particles of Sf 0-7 in the runners occurred without a proportional increase in the faster floating particles of Sf 7-l2. This finding suggests that running reduced the mass of the smaller LDL particles as opposed to shifting the lipoprotein mass distribution from the smaller to the larger LDL particles.

Table 1.

Comparison of age, body mass index, lipids, lipoproteins, and hepatic and lipoprotein lipase measurements in cross-sectional samples of long-distance runners and sedentary men.

| Runners (mean±SD) |

Nonrunners (mean±SD) |

Difference (mean±SE) |

Significance † (P) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 46.9±7.5 | 45.7±6.1 | 1.3±2.3 | 0.81 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.6±2.0 | 25.1±3.3 | −2.5±0.7 | 0.006 |

| Lipids and lipoproteins | ||||

| Plasma total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 190.9±36.6 | 217.0±31.1 | −26.1±11.3 | 0.02 |

| Plasma total triglycerides (mg/dL) | 70.8±35.0 | 123.0±59.3 | −52.2±12.5 | 0.001 |

| Plasma HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 64.9±12.5 | 49.6±8.7 | 15.3±3.8 | 0.0001 |

| Serum HDL-mass of F1.20 0-1.5 (mg/dL) | 70.0±13.7 | 82.3±17.5 | −12.3±4.5 | 0.02 |

| Serum HDL-mass of F1.20 1.5-2.0 (mg/dL) | 51.2±8.4 | 52.3±7.8 | −1.1±2.6 | 0.98 |

| Serum HDL-mass of F1.20 2.0-9.0 (mg/dL) | 213.0±45.6 | 144.8±47.9 | 68.2±14.5 | 0.0002 |

| Plasma LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 116.1±30.7 | 147.0±27.5 | −30.9±9.5 | 0.004 |

| Serum LDL-mass of Sf 0-7 (mg/dL) | 138.4±45.3 | 227.6±67.9 | −89.2±15.6 | 0.0001 |

| Serum LDL-mass of Sf 7-12 (mg/dL) | 136.7±39.8 | 134.2±43.8 | 2.5±12.7 | 0.85 |

| Serum IDL-mass of Sf 12-20 (mg/dL) | 34.3±18.2 | 43.8±20.7 | −9.5±5.9 | 0.16 |

| Plasma VLDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 9.1±8.3 | 20.4±11.7 | −11.3±2.8 | 0.001 |

| Serum VLDL-mass of Sf 20-400 (mg/dL) | 36.8±41.6 | 106.1±72.0 | −69.3±15.0 | 0.001 |

| Postheparin lipase activity | ||||

| Lipoprotein lipase (mEq fatty acid/ml/h) | 5.0±1.8 | 3.6±1.2 | 1.4±0.6 | 0.04 |

| Hepatic lipase (mEq fatty acid/ml/h) | 4.1±2.1 | 6.5±2.6 | −2.4±0.9 | 0.02 |

Sample sizes are 12 runners and 64 nonrunners for all lipid and lipoprotein variables, age and body mass index; and 12 runners and 16 nonrunners for lipoprotein and hepatic lipase measurements.

All significance levels are obtained from two sample Wilcoxon sign rank tests.

Fig 2.

Upper panel displays the average distributions of serum low-density lipoprotein mass concentration by flotation rate for male runners (N=12) and male nonrunners (N=64). The lower panel displays the LDL difference curve for runners minus nonrunners.

Intermediate and Very-Low-Density Lipoproteins

Table 1 reveals no significant group differences in serum IDL concentrations, but significantly lower triglyceride, VLDL-cholesterol, and VLDL-mass concentrations (total mass of Sf 20-400 and individually significant for the 10 flotation intervals occurring within the Sf 20-200 region) in runners than nonrunners.

High-Density Lipoproteins

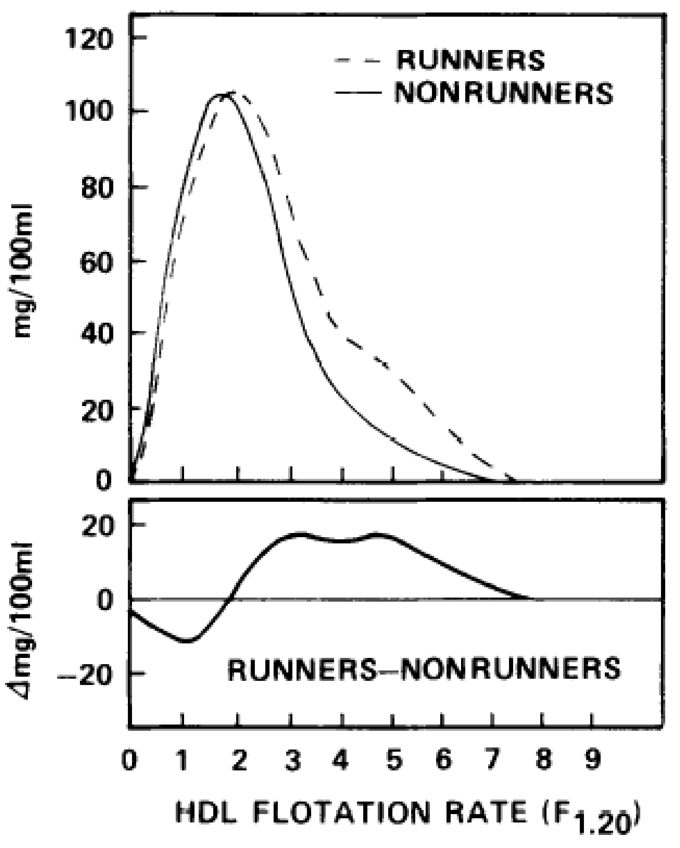

Figure 3 shows that runners had less HDL-mass for the three individual flotation intervals between F1.20 0-l.5 (predominately HDL3) and more HDL-mass for the individual flotation intervals between F1.20 2.0-9.0 (predominately HDL2) than nonrunners. The mean total serum lipoprotein mass concentrations of these two HDL regions were also statistically significant between the groups (Table 1). The difference curves (Fig 3, lower panel), calculated as the HDL-mass distribution of male runners minus the HDL-mass distribution of male nonrunners, reveals two peaks in the F1.20 2.0-9.0 region. These peaks correspond to two HDL2 subspecies: smaller, slower-floating particles of HDL2a and larger, faster-floating particles of HDL2b, that can be separated by ultracentrifugation and electrophoretic processes [11].

Fig 3.

Upper panel displays the average distribution of serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL) mass concentration by flotation rate for male runners (N=12) and male nonrunners (N = 64). The lower panel displays the HDL difference curve for runners minus nonrunners.

The traditional estimate of HDL3 as the total lipoprotein mass between F1.20 0-3.5 was not significantly different (P = 0.34) between runners (245.4±41.2 mg/dL) and nonrunners (236.6±35.7 mg/dL). The absence of a significant difference appears to be due to a multiplicity of effects within this region; compared to the mean serum concentrations in nonrunners, the HDL-mass of runners was lower for F1.20 0-1.5 and higher for F1.20 2-3.5 (Fig 3). HDL2, as estimated by the lipoprotein mass concentration within F1.20 3.5-9.0, was significantly higher (P = 0.0002) in runners (88.8±34.8 mg/dL) than nonrunners (42.7±31.0 mg/dL). Also, plasma HDL-cholesterol concentrations were 31% higher in runners than nonrunners.

Lipases

The 12 long-distance runners had significantly higher mean lipoprotein lipase activity and significantly lower mean hepatic lipase activity than the 16 nonrunners with lipase measurements. These findings are consistent with studies that have shown that adipose and muscle tissue of endurance-trained runners have higher lipoprotein lipase activities than those of nonrunners [24].

Adjustment for Adiposity

The long-distance runners were significantly leaner than the nonrunners (Table 1). However, an analysis of covariances (not displayed) suggests that the differences in lipoprotein concentrations are probably not entirely attributable to their differences in leanness. Adjustment for body mass index (kg/m2) reduces slightly the significance of the plasma cholesterol difference (P=0.06) and the serum HDL-mass difference of F1.20 0-l.5 (P=0.07), but all of the other lipoprotein differences identified as significant in Table 1 when unadjusted, remain significant at P≤0.05 after adjustment for body mass index.

Adjustment for body mass index reduced the significance of the difference between the runners and nonrunners for both post heparin lipoprotein lipase (P=0.09) and hepatic lipase activities (P=0.29). The coefficient relating body-mass index with lipase activities in the analysis of covariance was statistically significant for hepatic lipase (P=0.003) but not for lipoprotein lipase activity (P=0.09).

These findings for lipoproteins and lipases must be interpreted cautiously in light of the indirectness of the obesity measurement (for example, as compared to hydrostatically determined body density) and the potentially complex interrelationships that may exist between exercise-induced weight loss and changes in lipoprotein concentrations [7].

DISCUSSION

Our analyses suggest that low levels of LDL-cholesterol in men who have regularly engaged in long distance running for several years primarily reflects a reduction in the serum concentrations of the smaller, less-buoyant LDL particles. Runners were also more likely to have higher serum mass concentrations of the larger, more-buoyant HDL particles (mostly HDL2) and lower serum mass concentrations of triglyceride, total cholesterol, and VLDL cholesterol, and the smaller and less-buoyant HDL particles (predominantly the most dense particles of the HDL3 region) than sedentary men. Previous studies have reported that HDL2-cholesterol concentrations are elevated in association with exercise, whereas reports for HDL3-cholesterol are mixed, with studies reporting decreased, increased, or no change in HDL3-cholesterol in association with exercise [4,5,7,25–29]. These inconsistencies may relate in part to the existence of particle heterogeneity within these categories [30,31] and to the variable definitions of the HDL2 and HDL3 particle regions for different assays.

Analytic ultracentrifugation provides a means to discern lipoprotein subpopulation differences between runners and nonrunners with a high degree of resolution using lipoprotein mass concentrations within individual flotation intervals. Our previous one-year training study of initially sedentary men revealed a significant increase in HDL mass in association with exercise (i.e., miles run per week) for individual flotation intervals within the F1.203.5-9 and positive (albeit nonsignificant) correlations between exercise level and HDL-mass concentrations for intervals within F1.20 2.0-3.5 [32]. Among men who have run long distances for at least several years, statistically significant increases in HDL were observed over the entire F1.20 2.0-9.0 region. The lower serum concentrations of denser, smaller LDL particles in male long-distance runners compared to nonrunners is consistent with their elevated serum concentrations of less-dense HDL-mass of F1.20 2.0-9.0 and the strong inverse correlation which exists between these two lipoprotein subgroups [10].

Low Risk Lipoprotein Profiles of Long-Distance Runners

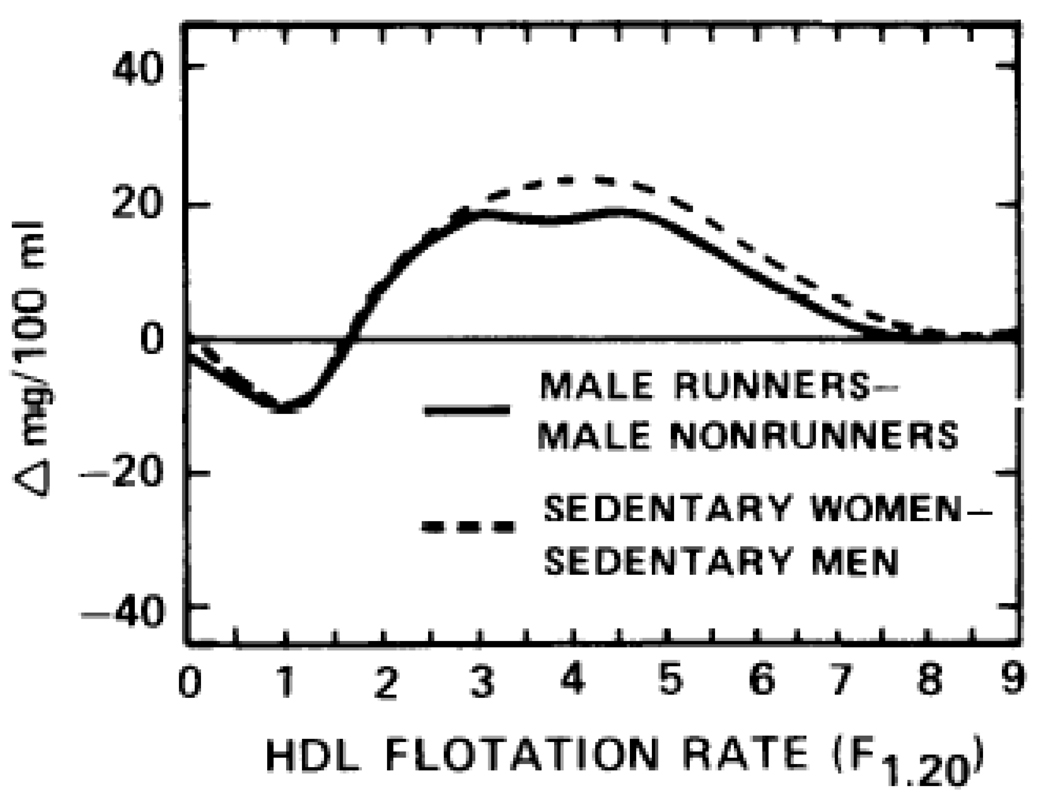

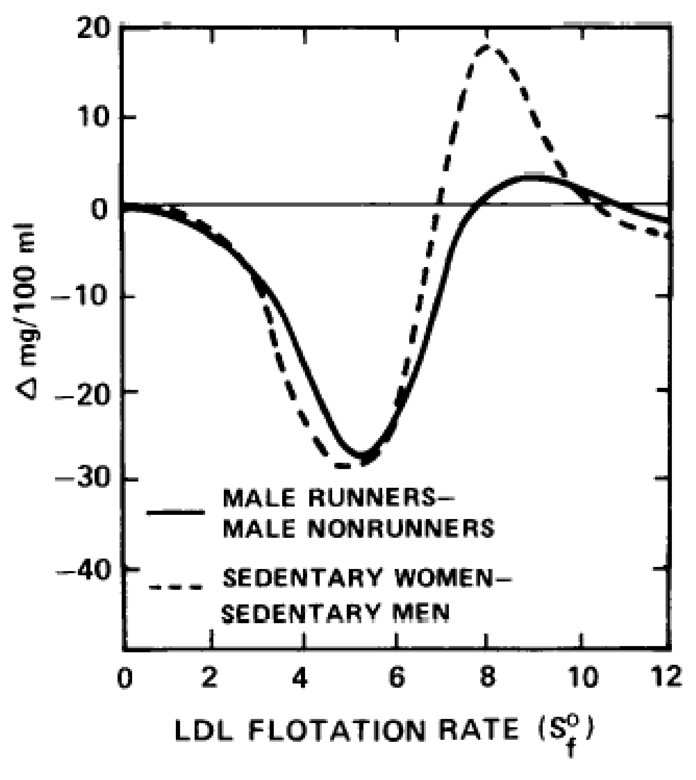

The lipoprotein profiles of the 12 male long-distance runners diverge from the lipoprotein profiles of sedentary men in the direction characteristic of the lipoprotein mass distribution in women [10]. Male long-distance runners and sedentary women in middle age both have significantly higher serum concentrations of HDL-mass between F1.20 2.0-9.0 (Fig 4) and significantly lower serum concentrations of LDL-mass between Sf 0-7 (Fig 5) and VLDL-mass between Sf20-400 (not displayed) than sedentary, middle-aged men. In men, running does not appear to affect the serum LDL concentrations of Sf 7-12, which are generally higher in sedentary women than in sedentary men (Fig 5).

Fig 4.

HDL difference curves for 36 sedentary women minus 55 sedentary men, and 12 male runners minus 64 male nonrunners, all of middle age. The sedentary men and women are a subset of a previously published cross-sectional study [10], who were selected to be between 30–55 years and not on oral contraceptives or estrogen supplements.

Fig 5.

LDL difference curves for 36 sedentary women minus 55 sedentary men, and 12 male runners minus 64 male nonrunners, all of middle age. The sedentary men and women are a subset of a previously published cross-sectional study [10], who were selected to be between 30–56 years and not on oral contraceptives or estrogen supplements.

While the similarities in lipoprotein profiles of long-distances runners and sedentary women do not necessarily require a common antecedent, both male long-distance runners [33–35] and sedentary women [23] have increased lipoprotein lipase activity and reduced hepatic lipase activity in post heparin plasma compared to sedentary men. Nikkila et al estimated that total body extrahepatic lipase activity of long-distance male runners was similar to the total body activity level of sedentary women [24]. In the case of runners, increased lipoprotein lipase activity may be a response to their high caloric flux over an extended period, and this may produce greater quantities of VLDL and chylomicron surface components to be incorporated into HDL particles [36]. Hepatic lipase is postulated to promote the removal of HDL lipid components in the liver [36]. Conceivably, reduced hepatic lipase activity could result in increased serum HDL2 concentrations in runners through slower clearance.

Reduced hepatic and increased lipoprotein lipase activity may also contribute to similarities in the LDL-lipoprotein mass concentrations in male runners and sedentary women. Adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase activity is reported to correlate negatively with serum LDL-mass concentrations of individual flotation intervals within Sf3-5 and positively with the mass contained within the Sf 7-10 region in sedentary, moderately obese middle-aged men examined cross-sectionally [37]. In cynomolgus monkeys, the administration of antisera to inhibit hepatic lipase activity has been reported to decrease serum concentrations of smaller LDL particles (Sf 0-9) and increase concentrations of larger LDL and IDL (Sf 9-20) [38].

Selection Bias

Cross-sectional comparisons of elite exercisers and sedentary men usually cannot distinguish the physiologic consequences of training from differences arising from self-selection. We have reported elsewhere a tendency for men who choose to take up running as a sport to have significantly higher plasma HDL-cholesterol and lower plasma triglyceride concentrations prior to participation in the sport [6]. In the present report we have attempted to minimize biases accruing from the self-selection of the 12 long-distance runners by comparing their lipoprotein values with the lipoprotein concentrations of men who were willing to participate later in a one-year exercise program. However, many of these sedentary men who were randomized into the exercise group failed to achieve the level of exercise apparently required to promote favorable changes in lipoprotein concentrations [5,6]. A more conservative statistical analysis of our data that takes into account both the willingness and ability of the men to run, compares the lipoprotein concentrations of the 12 long-distance runners with the baseline lipoprotein values of 21 sedentary men whose level of participation exceeded the median number of miles run by their group (ie, greater than 8.6 miles per week). With the exceptions of total cholesterol and HDL-mass of F1.20 0-1.5 (P=0.07), all of the significant lipoprotein differences of Table 1 remained significant at P≤0.05 for this more conservative comparison involving the much reduced sample of 21 sedentary men. Although we can not match precisely the current running levels of the long-distance runners with the future running levels of the sedentary men, we find little evidence from these analyses to suggest that self-selection produced the lipoprotein differences of Table 1.

Limitations and Caveat

Although dietary information was not collected for the 12 long-distance runners, other studies suggest that the composition of the runners’ and nonrunners’ diets are unlikely to have produced the observed differences in lipoprotein concentrations. For example, Blair et al found that long-distance runners consumed more calories than sedentary men, but that with the possible exception of higher intakes of alcohol and miscellaneous carbohydrates, the composition of the diets of the runners (as percent of total calories) was not different from the dietary composition for sedentary men [39]. (See, however, caveats expressed by Thompson, et al [40] concerning the self-reported diet records of runners.) Longitudinal [41] and cross-sectional [32] studies suggest that moderately higher alcohol intake primarily elevates HDL3, and has little effect on their HDL2 or LDL subspecies. This suggests that a higher alcohol intake for the runners than for the nonrunners may contribute in part to the elevation of some of the less-dense particles within the F1.20 0-3.5 region in the runners vis-a-vis nonrunners, but probably does not account for their other lipoprotein differences.

In conclusion, the higher serum concentrations of HDL-mass between F1.20 2.0-9.0 and the lower serum concentrations of HDL-mass of F1.20 0-l.5, LDL-mass of Sf 0-7, and VLDL-mass of Sf 20-400 reported here in runners vis-a-vis sedentary men could not be attributed to greater leanness or to self-selection in runners. The causal role of running is not necessarily proved by the lipoprotein differences between the exercising and the sedentary men, and caution should be used in extrapolating these results obtained for a modest, select sample of men to more general populations. Nevertheless, the similarities between the lipoprotein profiles of male long-distance runners and sedentary women suggest that long-distance running may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease through metabolic changes similar to those operating in women.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants HL-24462 and HL-18574 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and computer equipment donated by the Macintosh Division of Apple Computer Inc. Cupertino, Calif. Address reprint requests to Paul Williams, Stanford Center for Research in Disease Prevention, Suite B. 730 Welch Rd. Stanford, CA 94305.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thompson P, Lazarus B, Cullinane E, et al. Exercise, diet. or physical characteristics as determinants of HDL-levels in endurance athletes. Atherosclerosis. 1983;46:333–339. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(83)90182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huttunen JK, Lansimies E, Voutilainen E, et al. Effects of moderate physical activity on serum lipids. Circulation. 1979;60:1220–1229. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.60.6.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez SA, Vial R, Balart L, et al. Effect of exercise and physical fitness on serum lipids and lipoproteins. Atherosclerosis. 1974;20:l–9. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(74)90073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood PD, Williams PT, Haskell WL. Physical activity and high-density lipoproteins. In: Miller NE, Miller GW, editors. Clinical and Metabolic Aspects of High-Density Lipoproteins. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1984. pp. 133–165. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wood PD, Haskell WL, Blair SN, et al. Increased exercise level and plasma lipoprotein concentrations: a one-year randomized study in sedentary middle-aged men. Metabolism. 1983;32:31–39. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(83)90152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams PT, Wood PD, Haskell WL, et al. The effects of running mileage and duration on plasma lipoprotein levels. J Amer Med Assoc. 1982;247:2674–2679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams PT, Wood PD, Krauss RM, et al. Does weight loss cause the exercise-induced increase in plasma high-density lipoproteins? Atherosclerosis. 1983;47:173–185. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(83)90153-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krauss RM, Burke DJ. Identification of multiple subclasses of plasma low-density lipoproteins in normal humans. J Lipid Res. 1982;23:97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen MS, Krauss RM, Lindgren FT, et al. Heterogeneity of serum low-density lipoproteins in normal human subjects. J Lipid Res. 1981;22:236–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krauss RM, Lindgren FT, Ray RM. Interrelationships among subgroups of serum lipoproteins in normal human subjects. Clin Chim Acta. 1980;104:275–290. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(80)90385-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson DW, Nichols AN, Pan SS, et al. High density lipoprotein distribution. Resolution and determination of three major components in a normal population sample. Atherosclerosis. 1978;29:161–179. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(78)90005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albrink MJ, Krauss RM, Lindgren FT, et al. Intercorrelations among plasma high density lipoprotein, obesity and triglycerides in a normal population. Lipids. 1980;15:668–676. doi: 10.1007/BF02534017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krauss RM. Regulation of high density lipoprotein levels. Medical Clin of North Amer. 1982;66:403–430. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)31427-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller GJ, Miller NE. Plasma high-density lipoprotein concentrations and the development of ischaemic heart-disease. Lancet I. 1975:l6–19. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maciejko JJ, Holmes DR, Kottke BA, et al. Apolipoprotein A-l as a marker for angiographically assessed coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:385–389. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198308183090701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gofman JW, Young W, Tandy R. lschemic heart disease, atherosclerosis, and longevity. Circulation. 1966;34:679–697. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.34.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller NE, Hammett F, Saltissi S, et al. Relation of angiographically defined coronary artery disease to plasma lipoprotein subfractions and apolipoproteins. Br Med J. 1981;282:l741–1744. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6278.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy RI, Brensike JF, Epstein SE, et al. The influence of changes in lipid values induced by cholestyramine and diet on the progression of coronary artery disease: Results of the NHLBI Type II Coronary Intervention Study. Circulation. 1984;69:325–337. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.69.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballantyne FC, Clark RS, Simpson HS, et al. High density and low density lipoprotein subfractions in survivors of myocardial infarction and in control subjects. Metabolism. 1982;31:433–437. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(82)90230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stamler J. Population Studies. In: Levy RI, Rifkind B, Dennis BH, et al., editors. Nutrition, Lipids and Coronary Heart Disease. New York: Raven Press; 1979. pp. 25–88. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipid and Lipoprotein Analysis. Washington DC: HEW Publication No. NIH 75-628, US Government Printing Office; 1974. Lipid Research Clinics Manual of Laboratory Operations (vol 1) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ewing AM, Freeman NK, Lindgren FT. The analysis of human serum lipoprotein distributions. In: Paoletti R, Kritchevsky K, editors. Advances in Lipid Research. New York: Academic Press; 1965. pp. 25–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krauss RM, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Selected measurement of two lipase activities in postheparin plasma from normal subjects and patients with hyperlipoproteinemia. J Clin Invest. 1974;54:1107–1124. doi: 10.1172/JCI107855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nikkila EA, Taskinen MR, Rehunen S, et al. Lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle of runners: relation to serum lipoproteins. Metabolism. 1978;27:1661–1671. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(78)90288-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood PD, Haskell WL. The effect of exercise on plasma high density lipoproteins. Lipids. 1979;14:417–427. doi: 10.1007/BF02533428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nye ER, Carlson K, Kirstein P, et al. Changes in high density lipoprotein subfractions and other lipoproteins induced by exercise. Clin Chem Acta. 1981;13:51–57. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(81)90439-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ballantyne FC, Clark RS, Simpson HS, et al. The effect of moderate physical exercise on the plasma lipoprotein subfractions of male survivors of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1982;65:913–918. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.65.5.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuusi T, Nikkila EA, Saarinen P, et al. Plasma high density lipoproteins HDL, and HDL, and postheparin plasma lipases in relation to parameters of physical fitness. Atherosclerosis. 1982;41:209–219. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(82)90186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LePorte RE, Brenes G, Dearwater S, et al. HDL cholesterol across a spectrum of physical activity from quadriplegia to marathon running. Lancet. 1983;1:1212–1213. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanche PJ, Gong EL, Forte TM, et al. Characterization of human high-density lipoproteins by gradient gel electrophoresis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;665:408–419. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(81)90253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheung MC, Albers JJ. Characterization of lipoprotein particles isolated by immunoaffinity chromatography; particles containing A-J but no A-II. J Biochem. 1984;259:12201–12209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams PT, Krauss RM, Wood PD, et al. Associations of diet and alcohol intake with high density lipoprotein subclasses. Metabolism. 1985;34:524–530. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(85)90188-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stubbe I, Hannson P, Gustafson A, et al. Plasma lipoprotein and lipolytic enzyme activities during exercise training in sedentary men: Changes in high density lipoprotein subfractions and composition. Metabolism. 1983;32:1120–l128. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(83)90058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peltonen P, Marniemi J, Hietanen E, et al. Changes in serum lipids, lipoproteins, and heparin releasable lipolytic enzymes during moderate physical training in men. A longitudinal study. Metabolism. 1981;30:518–526. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(81)90190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marniemi J, Peltonen P, Vuori I, et al. Lipoprotein lipase of human postheparin plasma and adipose tissue in relation to physical training. Acta Physiol Stand. 1980;110:131–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1980.tb06642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinnunen PKJ, Virtonen JA, Vianio P. Lipoprotein lipase and hepatic endothelial lipase: Their roles in plasma lipoprotein metabolism. Atherosclerotic Reviews. 1983;1l:65–105. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haberek-Davidson A, Stefanick ML, Superko R, et al. Correlations of adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity with plasma lipoprotein subfractions in overweight men. Federation Proceedings. 1985;44:1893. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldberg JJ, Le NA, Paterniti JR, et al. Lipoprotein metabolism during acute inhibition of hepatic triglyceride lipase in the cynomolgus monkey. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:1184–l192. doi: 10.1172/JCI110717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blair SN, Ellsworth NM, Haskell WL, et al. Comparison of the nutrient intake in middle-aged men and women runners and controls. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 1981;13:310–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson PD, Cullinane E, Eshleman R, et al. Lipoprotein changes when a reported diet is tested in distance runners. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;39:368–374. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/39.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haskell WL, Camargo C, Williams PT, et al. The effect of cessation and resumption of moderate alcohol intake on serum high-density lipoprotein subfractions. New Engl J Med. 1984;310:805–810. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198403293101301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]