Abstract

From in vitro studies, flap endonuclease 1 (FEN1) has been proposed to play a role in the long patch (LP) base excision repair (BER) sub-pathway. Yet, the role of FEN1 in BER in the context of the living vertebrate cell has not been thoroughly explored. In the present study, we cloned a DT40 chicken cell line with a deletion in the FEN1 gene and found that these FEN1-deficient cells exhibited hypersensitivity to H2O2. This oxidant produces genotoxic lesions that are repaired by BER, suggesting that the cells have a deficiency in BER affecting survival. In experiments with extracts from the isogenic FEN1 null and wild type cell lines, the LP-BER activity of FEN1 null cells was deficient, whereas repair by the single-nucleotide BER sub-pathway was normal. Other consequences of the FEN1 deficiency also were evaluated. These results illustrate that FEN1 plays a role in LP-BER in higher eukaryotes, presumably by processing the flap-containing intermediates of BER.

Keywords: Flap endonuclease 1, base excision repair, DNA replication, oxidative stress

INTRODUCTION

Base excision repair (BER) is the major system for repairing oxidized, alkylated and deaminated DNA bases in the genomic DNA (1). BER consists of two major sub-pathways known as single-nucleotide (SN)-BER and long-patch (LP)-BER that are distinguished by their repair patch sizes and by the enzymes involved. BER is initiated by a DNA glycosylase that cleaves the glycosidic bond between the modified base and the deoxyribose phosphate backbone (2). This process, however, generates mutagenic and toxic BER intermediates, such as abasic (AP) sites and strand breaks (3). In one form of SN-BER, AP endonuclease 1 (APE1) incises the DNA backbone 5′ to the abasic site sugar and DNA polymerase beta (POLβ) incorporates the appropriate nucleotide into the gap and eliminates the 5′ AP site via its 5′-deoxyribose-phosphate (dRP) lyase activity (4, 5). Finally, DNA ligase I or III seals the nick in the lesion-containing DNA strand to complete SN-BER. In addition to formation during BER, approximately 9,000 AP sites are generated spontaneously in each mammalian cell per day, and these sites also are normally repaired by SN-BER and LP-BER (6, 7). Furthermore, reactive oxygen species oxidize deoxyribose in the DNA backbone resulting in single-strand breaks (SSBs) (8, 9). The 5′-oxidized deoxyribose lesions are resistant to the dRP lyase activity of POLβ, but can be excised by the LP-BER sub-pathway (10). In the LP-BER sub-pathway, DNA polymerase β/δ/ε incorporates 2–15 nucleotides into the repair patch and displaces the lesion-containing strand to generate a 5′-flap that is then excised by FEN1 (11, 12) and, finally, a DNA ligase completes the LP-BER process. In addition, oxidized bases in DNA are excised by bifunctional glycosylases, such as NTH1, OGG1, NEIL1, NEIL2, and NEIL3 (13). These enzymes are capable of AP lyase activity that nicks the DNA strand in association with the base removal reaction (14, 15). This type of bifunctional glycosylase activity leaves the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde blocked, and APE or polynucleotide kinase (PNK) is required to remove the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde blocking group prior to gap-filling DNA synthesis (16) and completion of SN-BER or LP-BER. Although DT40 cells lacking POLβ are not hypersensitive to H2O2 in cell survival assays, after exposure to H2O2 in POLβ null DT40 cells, we consistently detected a higher accumulation of SSBs than in wild type DT40 cells (17, 18). These results suggested that under oxidative stress conditions, POLβ may be involved in gap-filling DNA synthesis for SN-BER initiated by bi-functional DNA glycosylases. In the absence of POLβ, other DNA polymerases could back-up this DNA synthesis role with relatively high efficiency. Because of the constant generation of endogenous mutagens, AP sites and their oxidation leading to SSBs are believed to be the most common type of DNA damage in cells (19, 20).

Loss of BER genes (e.g., APE1, POLβ, FEN1, and X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 1 [XRCC1]) leads to embryonic lethality in mice (21–25), suggesting a critical need for repair of BER intermediates during mouse embryogenesis. The importance of POLβ in SN-BER has also been demonstrated by using POLβ-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (26). POLβ-deficient MEFs are hypersensitive to methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), among other alkylating agents. The hypersensitivity to MMS appears to be due to the loss of dRP lyase activity of POLβ, but not from a deficiency in polymerase activity (5). However, the absence of POLβ in MEFs does not alter cell doubling times nor make them strongly sensitive to H2O2, but does make them hypersensitive to alkylating agents. The lack of strong sensitivity towards H2O2-induced damage may be due to polymerases λ, ι or Q being used as back-up enzymes in the repair of oxidized bases (17, 18, 27) or to an alternative base incision repair pathway (28).

In eukaryotic cells, FEN1 is believed to play critical roles in DNA metabolism, including removal of the RNA primer segment at the 5′ end of Okazaki fragments during replication (6, 9, 29). Upon deletion of the FEN1 homolog (Rad27) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cerevisiae), cells are viable and exhibit an elevated spontaneous mutational frequency, indicating that the processing of Okazaki fragments during replication can still occur, but at the expense of genome integrity. The processing of Okazaki fragments in the absence of Rad27 is thought to be performed by the exonuclease activity of POLδ (30–33). S. cerevisiae Rad27 mutant cells also exhibit hypersensitivity to MMS. This is not surprising, as the only form of robust BER present in S. cerevisiae is LP-BER (6, 34–37) and thus the loss of Rad27 attenuates the LP-BER of the damage caused by MMS. DT40 FEN1 knockout cells also show a slow rate of cell proliferation and hypersensitivity toward MMS and are hypersensitive to H2O2, as well (4). The reason for their sensitivity toward MMS and H2O2 is not known, but it could be the result of a deficiency in LP-BER. It is important to note that both S. cerevisiae and DT40 cells are believed to utilize homologous recombination to a greater extent than many other eukaryotic cell types (1). Therefore, homologous recombination could play a role to back-up the base excision repair pathway in S/G2 cells, particularly in the absence of Rad27/FEN1-dependent LP-BER (38, 39).

In the present study, we utilized DT40 cells and cell extracts to investigate the impact of FEN1 gene deletion on DNA repair capacity, cell viability, and genomic DNA synthesis. We found that extract from FEN1 null cells exhibited lower uracil-DNA BER capacity than extract from wild type cells, and using an assay specific for the LP-BER sub-pathway, the reduction in BER capacity appeared to be due to a deficiency in the LP-BER sub-pathway. FEN1 null cells showed an increased level of apoptosis compared to the wild type cells after exposure to H2O2. Using a DNA fiber-labeling strategy that allows one to visualize replication on a large number of individually-labeled replication units, we found that FEN1 null cells had a slower replication rate than wild type cells. In addition, a higher proportion of replication forks stalled in FEN1 null cells after DNA damage, suggesting that FEN1-mediated LP-BER serves an essential function in preventing DNA replication forks from prematurely terminating at oxidative DNA damage sites. These observations represent enhanced understanding of the importance of FEN1 in the LP-BER sub-pathway in vertebrates. By making use of LP-BER assays of extracts, our results confirm and extend the results reported by Matsuzaki et al. (4).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Wild type DT40 and DT40-derived mutant cells (4, 40) were cultured as a suspension in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 39.5°C. The culture medium consisted of RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma), 1% chicken serum (Sigma and Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen).

DNA substrate for the BER assay

The DNA substrate for the 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine (8oxoG)-DNA BER assay was a 100-bp duplex DNA constructed by annealing two synthetic oligodeoxyribonucleotides (Operon Biotechnologies, Inc.) to introduce a 8oxoG:C base pair at position 23: 5′-CGAGTCATCTAGCATCCGTATCXACTCGTTACGTGATCGTGTACTGCATGTGTATGTCGTATGATGTCTATGTCTCGAACTACGTAGACTTACTCATTGC-3′ and 5′-GCAATGAGTAAGTCTACGTAGTTCGAGACATAGACATCATACGACATACACATGCAGTACACGATCACGTAACGAGTCGATACGGATGCTAGATGACTCG-3′, where X represents 8oxoG. For the DNA substrate for the uracil-DNA BER assay was a 35-bp duplex DNA constructed by annealing two synthetic oligodeoxyribonucleotides (Oligos Etc., Inc.) to introduce a G:U base pair at position 15: 5′-GCCCTGCAGGTCGAUTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGTAC-3′ and 5′-GTACCCGGGGATCCTCTAGAGTCGACCTGCAGGGC-3′.

Whole cell extract preparation

Cell extracts were prepared as previously described (41). Briefly, cells were washed twice with PBS at 25°C, collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in an equal volume of Buffer I (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 200 mM KCl, and protease inhibitor cocktail [Boehringer Mannheim]). An equal volume of Buffer II (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 200 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 40% glycerol, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 2 mM DTT, and protease inhibitor cocktail) then was added. The suspension was rotated for 1 hr at 4°C, and the resulting extract was clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant fraction was used in the in vitro BER assays. The protein concentration of extracts was determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

In vitro BER assay using oligonucleotide substrate

The “total BER” assay (final volume 10 μl) was performed with the 100-bp 8oxoG containing oligonucleotide DNA substrate or 35-bp uracil-containing oligonucleotide DNA substrate as described above. The duplex oligonucleotide (50 nM) was incubated with 10 μg of DT40 whole cell extract prepared from wild type or FEN1 null cells in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DTT, and 4 mM ATP. For the assay of “total BER”, incubation was conducted in the presence of 20 μM each dATP, dGTP, and dTTP, and 2.3 μM [α-32P]dGTP for 8oxoG BER analysis or [α-32P]dCTP for uracil-BER analysis at 37°C for 2, 5, 10, and 20 min.

For the 8oxoG LP-BER assay, 8oxoG-containing oligonucleotide was 5′-end labeled by incubation with OptiKinase (USB Corporation) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP for 30 min at 37°C. The labeled DNA was then annealed with the complementary strand, and the DNA was purified with a MicroSpin G-25 column (GE Healthcare). The 32P-labeled duplex oligonucleotide substrate was subjected to a similar incubation in the presence of 2 μM dGTP and 50 μM ddCTP as described previously (41). For the uracil LP-BER assay, non-end labeled duplex uracil containing DNA substrate was incubated in the presence of 2.3 μM [α-32P]dCTP and 50 μM ddTTP, with or without 20 nM and 100 nM purified FEN1 at 37°C for 1, 5 and 10 min. In all incubations, LP-BER is quantified by measuring the amount of 2-nucleotide intermediate formed, and SN-BER is quantified by measuring the amount of ligated BER product formed.

The reaction products were analyzed by 15% polyacrylamide denaturing gel electrophoresis. The initial rate of the in vitro BER reaction was determined from a plot of PhosphorImager radiolabel signal in ligated BER product (representing total BER or SN-BER) or in 2-nucleotide addition product (representing the intermediate of LP-BER) against each time point. The linear relationship between activity and time of incubation for each extract was obtained. [γ-32P]ATP (7,000 Ci/mmol) was from MP Biomedicals. [α-32P]dGTP (6,000 Ci/mmol) and [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol) were from Perkin Elmer Life Sciences and GE Healthcare, respectively. Purified human FEN1 was prepared as described (42).

Construction of expression vectors and transfection

To construct chicken FEN1 expression vectors, full-length chicken FEN1 cDNAs were inserted into the multi-cloning site of the pCR3-loxP-MCS-loxP expression vector (43). The expression plasmid (pCR3-loxP-FEN1/IRES-EGFP-loxP) was linearized and electroporated with a Gene Pulser apparatus (BioRad) at 550 V and 25 μF. Subsequently, the cells were transferred into 20 ml fresh medium and incubated for 24 hrs. Cells were resuspended in 80 ml of medium containing G418 (2 mg/ml, Sigma) and divided into four 96-well plates. After 7–10 days, drug-resistant colonies in the 96-well plates were transferred to 24-well plates. The drug-resistant colonies stably expressing chicken FEN1 were utilized for cell survival assays and molecular fiber combing analysis.

Clonogenic assay

Colony formation was assayed in medium containing methylcellulose as described previously (44). To determine sensitivity to H2O2, cells were treated with various concentrations of H2O2 for 30 min at 39.5°C in complete medium and then washed twice with PBS. After serial dilution, the cells were plated in triplicate in the medium described above in 6-cm plates and were incubated at 39.5°C for 6–7 days. Colonies were counted, and percent survival was determined relative to the number of colonies obtained from untreated cells.

DNA fragmentation analysis

Cells (3×105) were harvested, and DNA was purified using the AquaPure DNA extraction kit (Bio-Rad). The extracted DNA was resuspended in 50 μl of 10 mM Tris buffer with 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), and analyzed by electrophoresis on a 2.0% agarose gel in TAE buffer. DNA bands were visualized under UV light after ethidium bromide staining.

Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis

For apoptosis analysis, cells were washed twice in cold PBS and resuspended in binding buffer (10 mM HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2) at a concentration of 106 cells/ml. One-hundred μl of cells was transferred to a FACScan tube with the addition of 0.1 μg fluorescein-conjugated annexin V (IQ Corp, Groningen, Netherlands) and 0.5 μg propidium iodide (PI). Cells were mixed gently and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 15 min. Then, 400 μl of binding buffer was added to the sample, and the sample was analyzed by flow cytometry within 1 hr of staining. The data from 104 cells were collected and analyzed using LYSIS II software. The signals of green fluorescence (FL1; annexin V) and orange fluorescence (FL2; PI) were measured by logarithmic amplification.

Measurement of iododeoxyuridine (IdU) incorporation in cells treated with H2O2

Cells were treated with H2O2 for 10 min, followed by its quenching with catalase (18 units/mL). Cells were further incubated with IdU at 100 μM for 20 min. After centrifugation, cells were washed with cold PBS and stored at −80°C until DNA isolation. DNA was isolated from cultured cells using the PureGene DNA extraction kit (Gentra Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). Briefly, cell pellets were thawed and lysed in lysis buffer supplemented with 20 mM 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidinoxyl (TEMPO, Aldrich). Proteins were precipitated and removed by centrifugation, and the DNA/RNA in the supernatant was precipitated with isopropyl alcohol. The DNA/RNA pellet was resuspended in a lysis buffer containing 20 mM TEMPO and incubated with RNase A (100 mg/ml) at 37°Cfor 30 min, followed by protein and DNA precipitation. The DNA pellet was resuspended in sterilized distilled water with 2 mM TEMPO, and DNA samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. Experimental samples (1 μg) or a reference DNA containing a high level of IdU were denatured in 220 μl TE buffer at 100°C for 10 min. After addition of an equal volume of 2 M ammonium acetate, denatured DNA was applied to nitrocellulose filters using a Minifold II apparatus (Schleicher & Schuell). The filters were soaked in 5x SSC (0.75 M NaCl, 75 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.0) for 15 min, dried and baked in a vacuum oven for 2 hrs at 80°C. Filters were incubated for 2 hrs at 37°Cwith blocking buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% casein, and 0.1% deoxycholic acid], followed by a 2-hr incubation at 37°C in blocking buffer containing anti-BrdU antibody (Becton Dickinson, 1:10,000). The filters were washed extensively in washing buffer [20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 0.26 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1%Tween-20] and treated with a labeled polymer (peroxidase-labeled polymer conjugated to goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse immunoglobulins, Daco) diluted 1:1,000 in hybridization buffer. After rinsing the membrane, the enzymatic activity on the membrane was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham). The membrane was exposed to X-ray film, and the developed film was analyzed using a Kodak image analysis system.

DNA fiber combing assay

DNA fiber combing analysis was conducted using logarithmically growing DT40 cells as described (45). Cells were pulsed with IdU, exposed to H2O2, and then pulsed with CldU. The cells were harvested and washed. A portion of cells was lysed on a glass slide and the DNA fibers were straightened (combed) and fixed. The presence of IdU or CldU was detected by immunostaining with red (AlexaFluor 594) and green (AlexaFluor 488) fluorescent antibodies, respectively.

RESULTS

FEN1 null cells are hypersensitive to H2O2

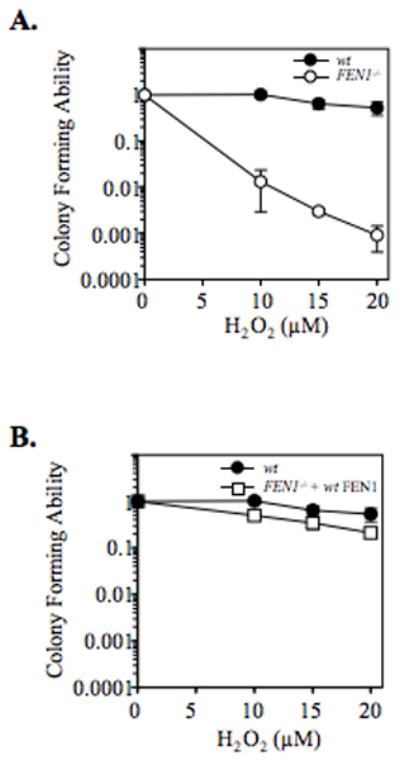

The availability of DT40 cells with homozygous deletion of the FEN1 gene enabled us to investigate the impact of FEN1 on cell tolerance toward oxidative stress. In a cell survival assay, FEN1 null cells were found to be hypersensitive to H2O2 (Figure 1A). The hypersensitivity was complemented by ectopic expression of chicken FEN1 (Figure 1B). These results are consistent with the idea that FEN1 plays a role in repair of H2O2 -induced DNA damage and that the FEN1 deficiency causes an accumulation of toxic BER intermediates under conditions of H2O2-induced stress. Since the FEN1 null cells showed considerable viability in the presence of H2O2, FEN1-independent protective pathways are present in these cells.

Figure 1. Sensitivity of FEN1 null cells to H2O2.

(A) Survival curves of wild type (wt) and FEN1 null cells (FEN1−/−), and (B) wild type (wt) and FEN1 null cells stably overexpressing FEN1 (FEN1−/− + wtFEN1 exposed to H2O2. Mean data and S.D. (bars) were from means of duplicate experiments.

BER activity for oxidative DNA lesion in FEN1-deficient DT40 cell extract

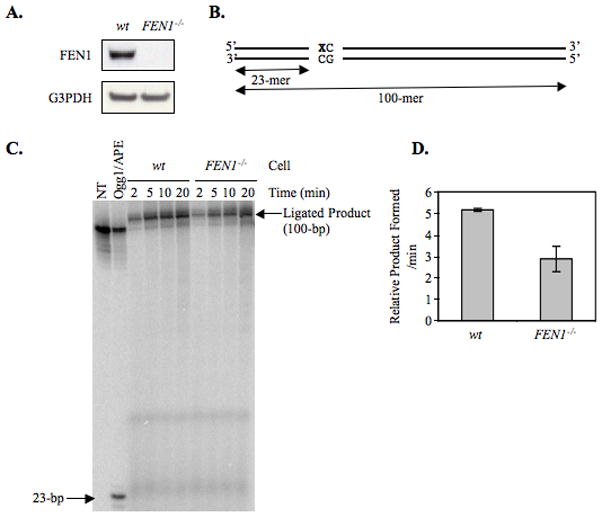

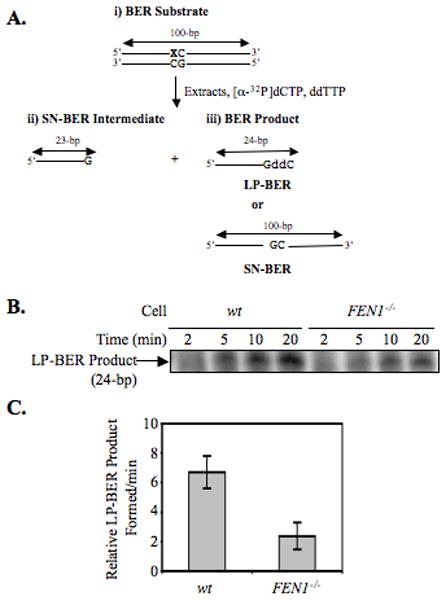

Because FEN1 functions in in vitro BER (11, 42, 46) in mammalian cells, the requirement of FEN1 in BER was addressed in wild type DT40 cells and their isogenic counterparts deficient in FEN1. First, to confirm the deletion of FEN1 in DT40-derived FEN1-deletion cells, immunoblotting analysis was performed using a specific antibody against FEN1. As expected, FEN1-deletion cells were completely devoid of FEN1 expression (Figure 2A). To examine a possible role of FEN1 in DT40 cell BER, an extract-based BER assay was performed using an oligonucleotide substrate containing 8oxoG as the oxidative DNA lesion initiating BER (Figure 2B). First, we measured the total BER capacity of wild type DT40 and FEN1 null cell extracts. The initial rate determination of 8oxoG-DNA repair with FEN1 null cell extract showed 44% reduction in BER activity, as compared to wild type cell extract (Figure 2, C and D). Next, since it is expected that FEN1 is involved in the LP-BER sub-pathway, the requirement of FEN1 in LP-BER was examined in the DT40 cell extracts. The discrimination between the LP-BER and SN-BER sub-pathways was achieved using an assay that depends on chain-termination after insertion of the first nucleotide in LP-BER gap-filling. This was accomplished by making use of ddCTP instead of dCTP in the reaction mixture (Figure 3A). In the SN-BER pathway, dGMP replaces the 8oxo-dGMP lesion, and the resulting BER intermediate is ligated to complete repair. In contrast, in the LP-BER pathway, ddCTP incorporation follows dGMP insertion, and the LP-BER intermediate accumulates because it cannot be ligated. After separation by 15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, the SN-BER product is observed as a 100-bp ligated molecule, whereas the LP-BER product is observed as the 24-bp intermediate molecule. Results of the in vitro LP-BER assay for 8oxoG DNA lesion demonstrated that the amount of LP-BER product was reduced (by 65%) in the FEN1 null cell extract (Figure 3, B and C), indicating that FEN1 plays a role in the LP-BER sub-pathway, but that FEN1 is not essential for LP-BER. This result correlates with the H2O2-sensitive phenotype in FEN1 null cells (Figure 1).

Figure 2. Kinetic analysis of BER for oxidative DNA damage using a 8oxoG-containing oligonucleotide duplex DNA substrate.

(A) After separation of whole cell extract by SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane that was then probed with anti-FEN1 (upper panel) and anti-G3PDH (lower panel) antibodies. (B-D) Incorporation of [α-32P]dGMP was measured as a function of incubation time using various DT40 cell extracts. (B) Schematic diagram of a 100-bp oligonucleotide containing an 8oxoG residue. ‘X’ represents the position of 8oxoG. (C) Photographs of PhosphorImager analysis illustrating 8oxoG-DNA BER are shown. The left two lanes show the marker oligonucleotide after the nicking reaction without and with Ogg1 and APE. The nicked product with Ogg1 and APE yields the 23-bp product. The mobility of the 100-mer oligonucleotide was slightly faster than the ligated product due to the presence of a 5′-phosphate group. (D) The relative amount of ligated BER product formed during a 20 min incubation is represented. The experiments were repeated 3 times, and the initial rates were calculated by using a curve fit program as a function of time of incubation. The average initial rate of activity of each extract for the in vitro 8oxoG-DNA BER reaction is shown in a bar diagram.

Figure 3. Analysis of SN- and LP-BER capacities for oxidative DNA damage using an 8oxoG-containing oligonucleotide duplex DNA substrate.

Incorporation of dGMP (G) was measured in the presence of ddCTP (ddC) to discriminate between SN-BER and LP-BER. (A) Schematic representation of the substrate DNA and predicted BER reaction products and intermediates. The sizes and intermediates were 1-nt addition, SN-BER (23-bp); 2-nt addition, LP-BER (24-bp); and complete BER product [ligated SN-BER (100-bp)]. A 100-bp oligonucleotide containing an 8oxoG residue at position 23 was utilized in the BER assay. In SN-BER, dGMP was incorporated in place of 8oxoG, and the intermediate was directly ligated to complete the repair. In LP-BER, ddCMP was incorporated following incorporation of dGMP in place of 8oxoG lesion, and the resulting dideoxy-terminated intermediate prevented subsequent primer extension DNA synthesis, as well as the ligation reaction. (B) Photograph of PhosphorImager image illustrating LP-BER analysis. A 100-bp duplex oligonucleotide containing an 8oxoG residue at position 23 was incubated with dGTP, ddCTP, and cell extracts. The incubations were performed with wild type (wt) or FEN1 null (FEN1−/−) DT40 cell extracts. (C) The relative amount of LP-BER product (24-mer) formed is represented. The experiments were repeated 3 times. The initial rate of activity of each extract was calculated as described in Figure 2C and shown in a bar diagram.

BER activity for uracil lesion in FEN1-deficient DT40 cell extract

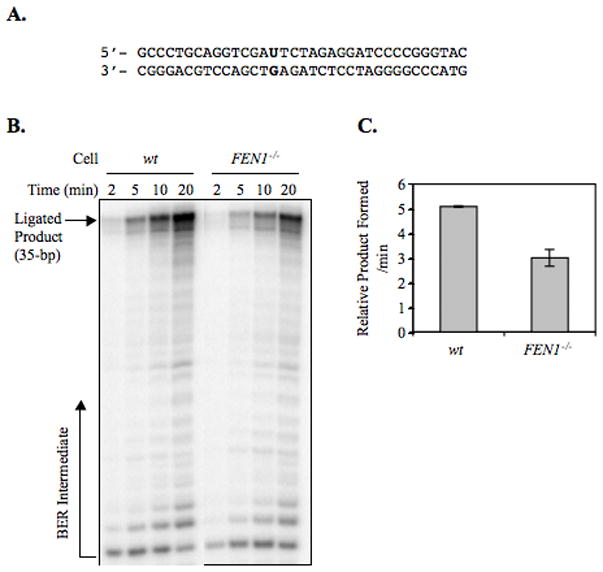

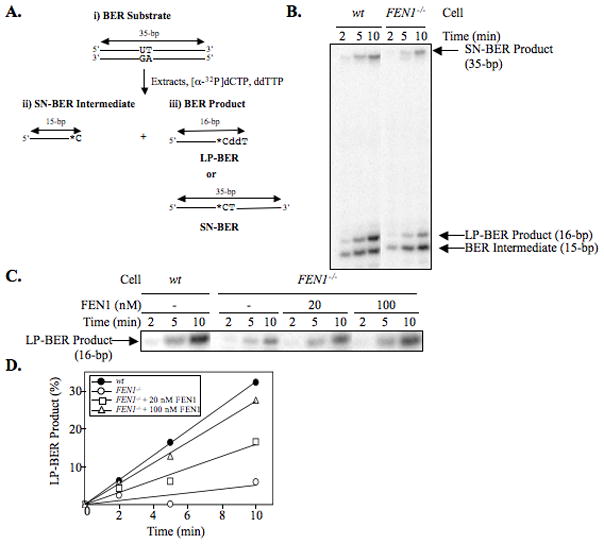

To confirm a possible involvement of FEN1 on DT40 cell LP-BER, in vitro uracil BER analysis was conducted (Figure 4A). The in vitro BER analysis is typically evaluated by making use of uracil-containing DNA substrate, revealing a protein involvement in BER (47). This in vitro analysis was applied to the DT40 cell system and revealed the involvement of Pol Q in LP-BER (18). In “total BER” analysis, the initial rate determination of uracil-DNA repair in FEN1 null cell extract showed a modest reduction (40%) in BER activity, as compared to wild type cell extract (Figure 4, B and C). The in vitro LP-BER analysis was accomplished by the same experimental strategy in the case of 8oxoG LP-BER, except we made use of ddTTP instead of ddCTP and the uracil lesion instead of the 8oxoG lesion (Figure 5A). Results of the in vitro uracil LP-BER assay confirmed the results of 8oxoG LP-BER assay, indicating that the amount of LP-BER product was reduced in the FEN1 null cell extract (Figure 5, B to D); the amount of SN-BER in wild type and FEN1 null cell extracts was similar (Figure 5B). The deficiency in LP-BER of FEN1 null extract was fully complemented by the addition of purified FEN1 (Figure 5, C and D). These results confirm that FEN1 plays a role in the LP-BER sub-pathway, but indicate that FEN1 is not essential for LP-BER. Based on studies with purified enzymes, the role of FEN1 is to excise the second nucleotide in the lesion-containing strand allowing gap-filling for the 2-nucleotide long repair patch (11). When FEN1 is absent, gap-filling stalls after one nucleotide is inserted into the gap.

Figure 4. Kinetic analysis of BER using a uracil-containing oligonucleotide duplex DNA substrate.

(B and C) Incorporation of [α-32P]dCMP was measured as a function of incubation time using various DT40 cell extracts. (B) Sequence of a 35-bp oligonucleotide containing a uracil residue. (C) Photographs of PhosphorImager analysis illustrating uracil-DNA BER are shown. (D) The relative amount of ligated uracil-BER product is represented.

Figure 5. Analysis of SN- and LP-BER capacities using a uracil-containing oligonucleotide duplex DNA substrate.

Incorporation of [α-32P]dCMP (*C) was measured in the presence of ddTTP (ddT) to discriminate between SN-BER and LP-BER. (A) Schematic representation of the substrate DNA and predicted BER reaction products and intermediates. The sizes and intermediates were 1-nt addition, SN-BER (15-bp); 2-nt addition, LP-BER (16-bp); and complete BER product (ligated SN-BER [35-bp]). A 35-bp oligonucleotide containing a uracil residue at position 15 was utilized in the BER assay. In SN-BER, [α-32P]dCMP was incorporated in place of uracil and directly ligated to complete the repair. In LP-BER, ddTMP was incorporated following incorporation of [α-32P]dCMP in place of uracil, and the resulting dideoxy-terminated intermediate prevented subsequent primer extension DNA synthesis, as well as the ligation reaction. The asterisks designate the position of the radiolabeled CMP group. (B and C) Photographs of PhosphorImager image illustrating LP-BER analysis. A 35-bp duplex oligonucleotide containing a uracil residue at position 15 was incubated with [α-32P]dCTP, ddTTP, and cell extracts. The incubations were performed with wild type (wt) or FEN1 null (FEN1−/−) DT40 cell extracts. (C) The reaction mixtures with FEN1 null extract were supplemented with 20 and 100 nM purified FEN1 as shown above the gel. (D) The relative amount of LP-BER product (16-mer) was plotted against incubation time.

Consequences of FEN1 deficiency: H2O2 causes caspase-dependent cell death

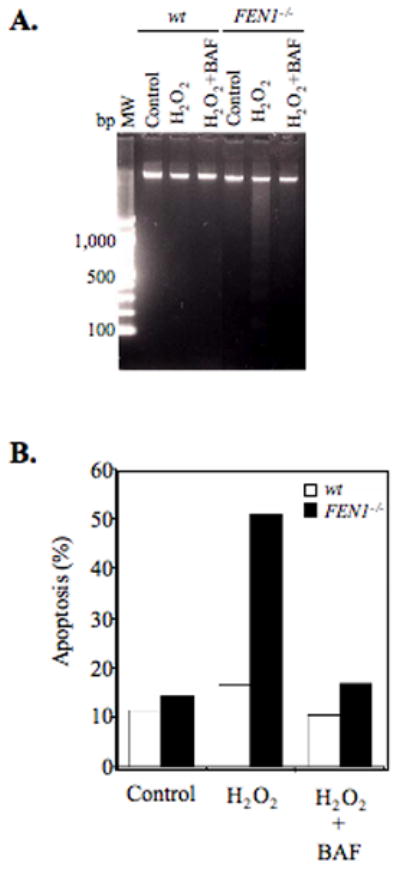

To better understand the mechanism by which FEN1 null cells are hypersensitive to H2O2 in the cell survival assay, apoptosis was assessed by DNA fragmentation and flow cytometric analyses. As early as 3 hrs after exposure to H2O2, fragmentation was detected in DNA extracted from FEN1-deficient cells. This was completely blocked by BAF, a pan-caspase inhibitor (Figure 6A). Next, DT40 cells treated with H2O2 were stained with a combination of annexin V and PI and analyzed by flow cytometry. By 3 hrs after H2O2 exposure, an increase in the percentage of early-stage apoptotic cells was observed (Figure 6B). Taken together, these results indicate that H2O2 treatment caused apoptosis in FEN1 null cells within 3 hrs of exposure.

Figure 6. Caspase-dependent cell death in FEN1-deficient cells exposed to H2O2.

(A) DNA fragmentation in wild type (wt) and FEN1 null (FEN1−/−) cells at 3 hrs after H2O2 (10 μM) treatment in the absence or presence of the caspace inhibitor BAF. (B) Frequency of apoptotic cells was expressed as the percentage of early-stage apoptosis (annexin V-positive/PI-negative) cells in the total number of cells assayed (e.g., sum of all quadrants).

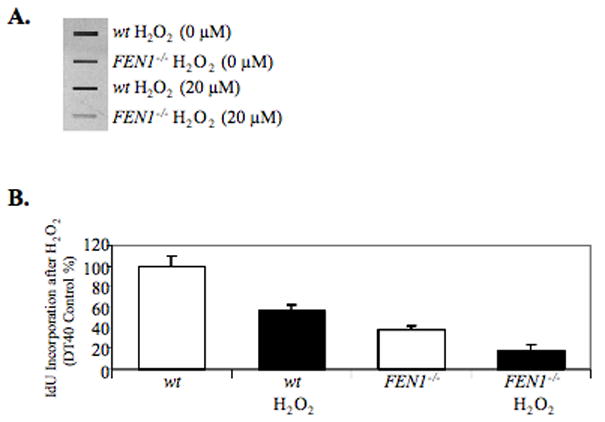

Consequences of FEN1 deficiency: H2O2 causes a decrease in DNA synthesis

To further characterize the effect of H2O2 treatment of FEN1 null cells, we developed a quantitative DNA synthesis assay based on IdU immuno-slot-blotting (ISB). This assay monitors DNA synthesis by measuring the amount of IdU incorporated into cellular DNA. A standard curve confirmed the ability of this ISB assay to measure IdU-DNA over a range of IdU levels. In the absence of H2O2 exposure, wild type DT40 cells showed greater IdU incorporation than FEN1 null cells (Figure 7, A and B). Both wild type and FEN1 null cells showed an inhibition of IdU incorporation after H2O2 exposure; the FEN1 null cells showed a reduction of IdU incorporation with H2O2 exposure (Figure 7, A and B).

Figure 7. IdU incorporation in FEN1-deficient cells exposed to H2O2.

(A) IdU Immuno-slot-blot X-ray film of blotted DNA samples extracted from cells exposed to PBS or H2O2 at 20 μM for 30 min. (B) Amount of IdU incorporated into genomic DNA in cells expressed as a percentage of the wild type (wt) control. The amount of IdU was quantified from multiple blots. Mean data and S.D. (bars) were from triplicate samples.

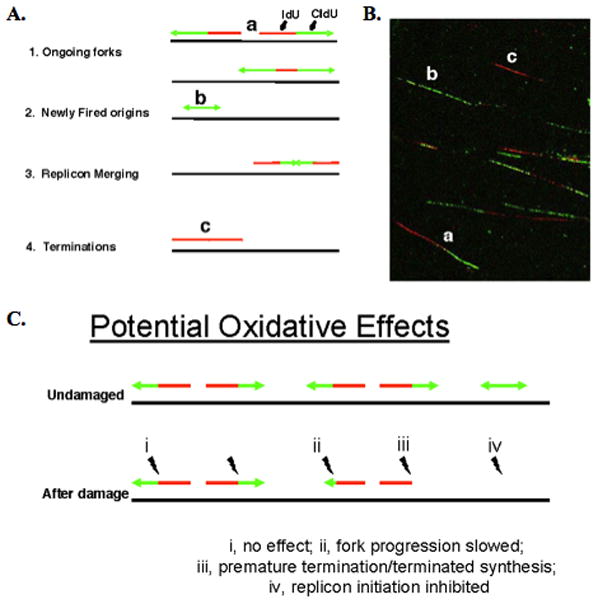

Consequences of FEN1 deficiency: H2O2-induced DNA damage alters DNA replication

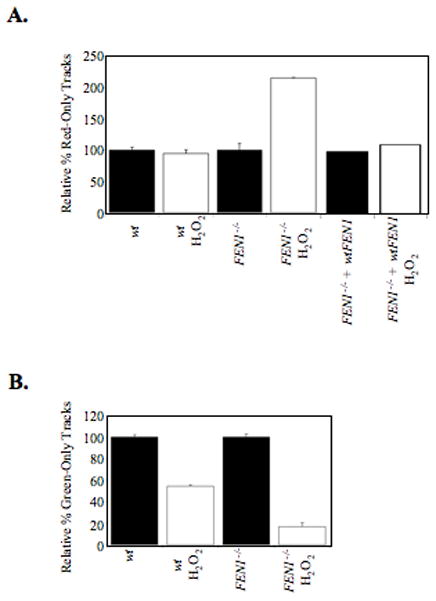

The DNA labeling technique (fiber combing) allows one to distinguish between ongoing replication forks (elongation), newly fired origins (initiation), and fork stalling events by identifying regions that have both labels, the second label only, or the first label only, respectively (Figure 8, A and B). At its level of sensitivity, this technique does not allow detection of tracks shorter than 500 bp. Therefore, any tracks incorporated during LP-BER would be completely undetected by fluorescence. The relative proportions of tracks with different label combinations can be used to evaluate interference with replication fork progression after DNA damage (Figure 8C) (48). As can be seen in Table 1 and Figure 9, exposure of wild type DT40 cells to H2O2 did not increase the relative percentage of IdU (red)-only tracks, suggesting that H2O2-induced damage was not a strong enough impediment to stop replication (i.e., cause the replication fork to terminate prematurely). However, H2O2 exposure did reduce the frequency of CldU (green)-only tracks (i.e., the firing of new origins). In contrast, exposure of FEN1 null cells to H2O2 both increased termination of replication and decreased replication initiation. This indicated that after H2O2-inducedDNA damage, the signals for checkpoint activation were greater in the FEN1 null cells, causing an increase in prematurely terminated replication forks and blocking initiation of forks. The ectopic expression of FEN1 reduced the amount of prematurely terminated replication forks after H2O2 exposure (Figure 9A). We conclude that FEN1 was required to sustain replication fork progression under conditions of H2O2-induced oxidative stress.

Figure 8. Visualization of various stages of replication by DNA fiber combing and immunostaining.

(A) Schematic illustration of results expected when genomic DNA from asynchronous cells (pulsed for 10 min with IdU followed by 20 min pulse with CldU) is aligned and straightened on a glass slide (fiber spread); the incorporated halogenated nucleotides are visualized by immunofluorescence. The various stages of DNA synthesis can be inferred by the presence and relative position of single and/or double-labeling in continuous replication tracks. The small letters in the schematic refer to the actual tracks illustrated in B. (B) Field of replication tracks as detected by fluorescence microscopy, containing representative examples of labeling. (C) Illustration of possible oxidative DNA damage effects on the various stages of replication.

Table I.

Distribution of tracks with CldU-only, IdU-only, or containing both labels

| % of Fibers Analyzed |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % IdU-Only (Premature Terminations) | % CldU-Only (New Origin Firing | % IdU-CldU conjoined tracks (Fork Elongation) | Experiments | ||

| wt |

Not treated |

40% | 11% | 49% | n=5 |

| H2O2 | 38% | 6% | 56% | n=5 | |

| FEN1−/− |

Not treated |

32% | 24% | 38% | n=2 |

| H2O2 | 68% | 4% | 25% | n=2 | |

Cells were pulsed with IdU, treated with H2O2 and then pulsed with CldU before preparing the DNA fibers. The numbers of tracks with CldU-only (green-only, second pulse), IdU-only (red-only, first pulse), or both (conjoined/red-green) were counted and converted to a percent of total scored. At least 150 intermediates were counted per experimental condition and per repeat.

Figure 9. H2O2-induced damage influences replication dynamics in wild type and full complement FEN1 null cells.

(A) Bar graph showing the increase in premature termination of replication tracks (labeled with first pulse (red) only, white bars) relative to the PBS-treated cells (dark bars) in wild type, FEN1 null, and FEN1 null cells with ectopic expression of FEN1. (B) Bar graph of the amount of tracks showing only the second pulse (green), indicating replication units initiated after H2O2 treatment relative to controls (dark bars) in the two cell types. At least 50 red-green tracks were analyzed per experimental condition.

DISCUSSION

The importance of FEN1 in LP-BER has been investigated in vivo using S. cerevisiae lacking Rad27: The deletion of the Rad27 gene caused hypersensitivity to MMS in cell survival assays. This hypersensitivity was reversed almost completely by disruption of the APN1 gene, a major AP endonuclease in yeast, indicating a significant role of FEN1 in the yeast base excision repair pathway (49). However, from these experiments, it is difficult to address the role in higher eukaryotes because the enzymes and sub-pathways of BER appear to be significantly different from those in yeast (50). DT40 cells, on the other hand, have both SN- and LP-BER sub-pathways, express PARP isoforms and other BER co-factors, and thus represent a valuable model for dissecting the roles of specific BER proteins in higher eukaryotes.

Using cell extract from wild type DT40, we found that both LP-BER and SN-BER sub-pathways could repair our BER substrate (~45% of the substrate was repaired by LP-BER and ~ 55% by SN-BER), and theses results were similar to those observed with mammalian cells (51). The absence of FEN1 caused the rate of overall BER to decrease by 65% for oxidative DNA damage (Figure 2D) and 40% for the uracil lesion (Figure 4C), and this appeared to be due to a reduction in LP-BER sub-pathway (Figures 3 and 5). Addition of purified FEN1 complemented the deficiency in LP-BER capacity in the FEN1 null cell extract (Figure 5B). We also found that LP-BER can occur even in the absence of FEN1 for both types of DNA damage (Figures 3C and 5C), indicating that there is an alternate pathway that can assume the function of FEN1. This may explain why FEN1 null DT40 cells are viable.

Replication Dynamics in FEN1-deficient cells under oxidative stress

Our results demonstrated that while FEN1 is dispensable in DT40 cells under physiological conditions, cells need FEN1 to survive increased oxidative stress. To gain insight into this hypersensitivity phenotype, we studied global levels of DNA replication. We observed that replication in wild type DT40 cells was ~40% lower under oxidative stress and was depressed even further in FEN1 null cells. This was consistent with a linkage between the repair role of FEN1 and DNA replication in the presence of oxidative stress. This linkage most likely was through the removal of oxidative damage in the replicating template. To gain further insight on this point, we used the fiber combing technique (Figures 8 and 9, Table 1) to visualize and characterize the stage of replication that was affected after cells were subjected to oxidative stress. We found that fork progression in FEN1 null cells was slower than in the wild type DT40 cells (data not shown). This reduction of fork movement was not severe enough to increase the number of premature fork terminations, indicating that DNA replication could proceed, albeit more slowly. When wild type cells were exposed to H2O2, the number of newly-fired origins was reduced, suggesting that H2O2 exposure elicited a checkpoint response (52, 53). FEN1 null cells exhibited a much stronger decrease in origin initiation, suggesting a stronger checkpoint response to oxidative stress.

H2O2-induced oxidative stress

H2O2 can initiate generation of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals through the transition metal-catalyzed Haber–Weiss reaction (8, 54). We previously demonstrated biphasic induction of oxidative DNA damage by H2O2 with a nearly linear increase in DNA damage between 60 and 600 μM H2O2 in HeLa cells (8). Concentrations of H2O2 that are able to induce oxidative DNA damage can be different among cell lines, most likely because of differences in antioxidant capacity. Oxidants, in general, are known to induce both apoptosis and necrosis in cells (55, 56), with the concentrations required being dependent on the cell type under study. For example, in response to 50 μM H2O2, Jurkat T-lymphocytes underwent apoptosis within 6 hrs, as measured by flow cytometry (57), and the phenomenon was associated with caspase activation. Human Burkitt lymphoma (B-cell origin, Raji) cells were more resistant to H2O2 compared with Jurkat T-lymphocytes: Raji cells underwent apoptosis after treatment with 0.5 mM H2O2 for 24 hrs (58), and there was no detectable cleavage of caspase-3 in Raji cells treated with 0.05 and 0.5 mM H2O2 for up to 9 hrs (59). In the present study, caspase-dependent apoptosis was observed in FEN1 null cells by 3 hrs after exposure to 10 μM H2O2. Since we made comparisons in isogenic DT40 cell lines, we conclude that the hypersensitivity of FEN1 null cells to H2O2-induced apoptosis was due to the lack of FEN1 function.

FEN1 in the excision of oxidized abasic sites in cells

FEN1-dependent LP-BER is believed to be the predominant BER pathway for removing a variety of 5′-end lesions resistant to β-elimination by POLβ. Deoxyribose structures, including chemically reduced abasic sites, abasic site analogues (e.g., tetrahydrofuran), and sugar lesions arising from either C-1′ or C-2′ oxidation of deoxyribose that have been initially cleaved on the 5′ side by APE1 are refractory to excision by POLβ (60, 61). Since the chemical structures of these 5′-end lesions prevent β-elimination by POLβ, they will be substrates for FEN1-dependent repair by LP-BER (62). Additionally, deoxyribose lesions oxidized at the C-5′ position, that still retain the nucleobase (63), also are substrates for FEN1-dependent LP-BER. In the absence of FEN1, abasic sites from C-1′ oxidized deoxyribose at the 5′-end of an SSB may lead to the formation of DNA-protein crosslinks especially between POLβ and C-1′ oxidized abasic sites (60, 62). Such DNA-protein crosslinks in cells could cause chromosomal aberrations and cell death. Our results, obtained from in vitro experiments, clearly support the idea that FEN1-dependent LP-BER plays a significant role in repairing oxidized DNA sugar damage in the context of the cell. We previously demonstrated that endogenous abasic sites likely include oxidized deoxyribose (7). The present study suggests an important role of FEN1 in the repair of oxidized abasic sites resistant to β-elimination by POLβ.

In conclusion, using the DT40 cell system, we demonstrated that: cell extract from FEN1 null cells was normal in SN-BER activity, but reduced in LP-BER sub-pathway activity; some FEN1-independent LP-BER activity exists in DT40 cells; FEN1 deficiency reduced DNA replication in cells under physiological conditions, as well as increased the amount of stalled replication forks under oxidative stress; and, in the absence of FEN1, oxidative stress induced apoptotic cell death. These results support the hypothesis that FEN1 plays an important role in the LP-BER sub-pathway in higher eukaryotes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sankar Mitra, Bruna Brylawski, Shuji Yonei, Tadayoshi Bessho, Brian Pachkowski, William Kaufmann, and Keith Caldecott for critically reading the manuscript. This research was supported in part by the Center for Environmental Health and Susceptibility Pilot Project Program, P42-ES05948, ES11746, P30-CA16086, P30-ES10126 from the National Institutes of Health, by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, and NIEHS (Z01-ES050158 and Z01-ES050159), by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R01-CA084493) and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education of Japan (KT). We also thank Bonnie E. Mesmer and Noriko Tano for expert secretarial assistance.

This research was supported in part by the Center for Environmental Health and Susceptibility Pilot Project Program, P42-ES05948, ES11746, P30-CA16086, P30-ES10126 from the National Institutes of Health, by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, and NIEHS (Zo1-ES050158 and Zo1-ES050159), by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R01-CA084493) and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education of Japan (KT).

Abbreviations

- FEN1

Flap endonuclease 1

- LP-BER

long patch-base excision repair

- SN-BER

single nucleotide-base excision repair

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- APE1

AP endonuclease 1

- POLβ

DNA polymerase beta

- dRP

5′-deoxyribose-5-phosphate

- SSBs

DNA single strand breaks

- XRCC1

X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 1

- MEFs

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- IdU

iododeoxyuridine

- CldU

chlorodeoxyuridine

- ISB

immuno-slot-blot

References

- 1.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, Schultz RA, Ellenberger T. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. 2. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beard WA, Wilson SH. Structure and mechanism of DNA polymerase β. Chem Rev. 2006;106:361–82. doi: 10.1021/cr0404904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meira LB, Burgis NE, Samson LD. Base excision repair. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2005;570:125–73. doi: 10.1007/1-4020-3764-3_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsuzaki Y, Adachi N, Koyama H. Vertebrate cells lacking FEN-1 endonuclease are viable but hypersensitive to methylating agents and H2O2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3273–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobol RW, Prasad R, Evenski A, et al. The lyase activity of the DNA repair protein β-polymerase protects from DNA-damage-induced cytotoxicity. Nature. 2000;405:807–10. doi: 10.1038/35015598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, Kao HI, Bambara RA. Flap endonuclease 1: a central component of DNA metabolism. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:589–615. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.012803.092453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakamura J, Swenberg JA. Endogenous apurinic/apyrimidinic sites in genomic DNA of mammalian tissues. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2522–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura J, Purvis ER, Swenberg JA. Micromolar concentrations of hydrogen peroxide induce oxidative DNA lesions more efficiently than millimolar concentrations in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1790–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waga S, Stillman B. Anatomy of a DNA replication fork revealed by reconstitution of SV40 DNA replication in vitro. Nature. 1994;369:207–12. doi: 10.1038/369207a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gros L, Ishchenko AA, Ide H, Elder RH, Saparbaev MK. The major human AP endonuclease (Ape1) is involved in the nucleotide incision repair pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:73–81. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Beard WA, Shock DD, Prasad R, Hou EW, Wilson SH. DNA polymerase β and flap endonuclease 1 enzymatic specificities sustain DNA synthesis for long patch base excision repair. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3665–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loeb LA, Preston BD. Mutagenesis by apurinic/apyrimidinic sites. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:201–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hegde ML, Hazra TK, Mitra S. Early steps in the DNA base excision/single-strand interruption repair pathway in mammalian cells. Cell Res. 2008;18:27–47. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dou H, Mitra S, Hazra TK. Repair of oxidized bases in DNA bubble structures by human DNA glycosylases NEIL1 and NEIL2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49679–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hazra TK, Hill JW, Izumi T, Mitra S. Multiple DNA glycosylases for repair of 8-oxoguanine and their potential in vivo functions. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2001;68:193–205. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(01)68100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiederhold L, Leppard JB, Kedar P, et al. AP endonuclease-independent DNA base excision repair in human cells. Mol Cell. 2004;15:209–20. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tano K, Nakamura J, Asagoshi K, et al. Interplay between DNA polymerases β and λ in repair of oxidation DNA damage in chicken DT40 cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:869–75. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshimura M, Kohzaki M, Nakamura J, et al. Vertebrate POLQ and POLβ cooperate in base excision repair of oxidative DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2006;24:115–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura J, La DK, Swenberg JA. 5′-nicked apurinic/apyrimidinic sites are resistant to β-elimination by β-polymerase and are persistent in human cultured cells after oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5323–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piersen CE, Prasad R, Wilson SH, Lloyd RS. Evidence for an imino intermediate in the DNA polymerase β deoxyribose phosphate excision reaction. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17811–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu H, Marth JD, Orban PC, Mossmann H, Rajewsky K. Deletion of a DNA polymerase β gene segment in T cells using cell type-specific gene targeting. Science. 1994;265:103–6. doi: 10.1126/science.8016642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsen E, Gran C, Saether BE, Seeberg E, Klungland A. Proliferation failure and gamma radiation sensitivity of Fen1 null mutant mice at the blastocyst stage. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5346–53. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5346-5353.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludwig DL, MacInnes MA, Takiguchi Y, et al. A murine AP-endonuclease gene-targeted deficiency with post-implantation embryonic progression and ionizing radiation sensitivity. Mutat Res. 1998;409:17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(98)00039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tebbs RS, Flannery ML, Meneses JJ, et al. Requirement for the Xrcc1 DNA base excision repair gene during early mouse development. Dev Biol. 1999;208:513–29. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xanthoudakis S, Smeyne RJ, Wallace JD, Curran T. The redox/DNA repair protein, Ref-1, is essential for early embryonic development in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1996;93:8919–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sobol RW, Horton JK, Kuhn R, et al. Requirement of mammalian DNA polymerase-β in base-excision repair. Nature. 1996;379:183–6. doi: 10.1038/379183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braithwaite EK, Kedar PS, Lan L, et al. DNA polymerase λ protects mouse fibroblasts against oxidative DNA damage and is recruited to sites of DNA damage/repair. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31641–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ischenko AA, Saparbaev MK. Alternative nucleotide incision repair pathway for oxidative DNA damage. Nature. 2002;415:183–7. doi: 10.1038/415183a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeMott MS, Shen B, Park MS, Bambara RA, Zigman S. Human RAD2 homolog 1 5′- to 3′-exo/endonuclease can efficiently excise a displaced DNA fragment containing a 5′-terminal abasic lesion by endonuclease activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30068–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.30068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ayyagari R, Gomes XV, Gordenin DA, Burgers PM. Okazaki fragment maturation in yeast. I. Distribution of functions between FEN1 AND DNA2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1618–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin YH, Ayyagari R, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA, Burgers PM. Okazaki fragment maturation in yeast. II. Cooperation between the polymerase and 3′-5′-exonuclease activities of Pol δ in the creation of a ligatable nick. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1626–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209803200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin YH, Garg P, Stith CM, et al. The multiple biological roles of the 3′-->5′ exonuclease of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase δ require switching between the polymerase and exonuclease domains. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:461–71. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.461-471.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin YH, Obert R, Burgers PM, Kunkel TA, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA. The 3′-->5′ exonuclease of DNA polymerase delta can substitute for the 5′ flap endonuclease Rad27/Fen1 in processing Okazaki fragments and preventing genome instability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2001;98:5122–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091095198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Budd ME, Campbell JL. Purification and enzymatic and functional characterization of DNA polymerase β-like enzyme, POL4 expressed during yeast meiosis . Methods Enzymol. 1995;262:108–30. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)62014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Budd ME, Campbell JL. The roles of the eukaryotic DNA polymerases in DNA repair synthesis. Mutat Res. 1997;384:157–67. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(97)00024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haltiwanger BM, Matsumoto Y, Nicolas E, Dianov GL, Bohr VA, Taraschi TF. DNA base excision repair in human malaria parasites is predominantly by a long-patch pathway. Biochemistry. 2000;39:763–72. doi: 10.1021/bi9923151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prakash S, Sung P, Prakash L. DNA repair genes and proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Genet. 1993;27:33–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.27.120193.000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bezzubova O, Silbergleit A, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Takeda S, Buerstedde JM. Reduced X-ray resistance and homologous recombination frequencies in a RAD54−/− mutant of the chicken DT40 cell line. Cell. 1997;89:185–93. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hochegger H, Sonoda E, Takeda S. Post-replication repair in DT40 cells: translesion polymerases versus recombinases. Bioessays. 2004;26:151–8. doi: 10.1002/bies.10403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buerstedde JM, Takeda S. Increased ratio of targeted to random integration after transfection of chicken B cell lines. Cell. 1991;67:179–88. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90581-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harrigan JA, Wilson DM, 3rd, Prasad R, et al. The Werner syndrome protein operates in base excision repair and cooperates with DNA polymerase β. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:745–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prasad R, Dianov GL, Bohr VA, Wilson SH. FEN1 stimulation of DNA polymerase β mediates an excision step in mammalian long patch base excision repair. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4460–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fujimori A, Tachiiri S, Sonoda E, et al. Rad52 partially substitutes for the Rad51 paralog XRCC3 in maintaining chromosomal integrity in vertebrate cells. EMBO J. 2001;20:5513–20. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamamoto K, Ishiai M, Matsushita N, et al. Fanconi anemia FANCG protein in mitigating radiation- and enzyme-induced DNA double-strand breaks by homologous recombination in vertebrate cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5421–30. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5421-5430.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dorn ES, Chastain PD, 2nd, Hall JR, Cook JG. Analysis of re-replication from deregulated origin licensing by DNA fiber spreading. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:60–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim K, Biade S, Matsumoto Y. Involvement of flap endonuclease 1 in base excision DNA repair. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8842–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singhal RK, Prasad R, Wilson SH. DNA polymerase beta conducts the gap-filling step in uracil-initiated base excision repair in a bovine testis nuclear extract. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:949–57. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Merrick CJ, Jackson D, Diffley JF. Visualization of altered replication dynamics after DNA damage in human cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20067–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400022200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu X, Wang Z. Relationships between yeast Rad27 and Apn1 in response to apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) sites in DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:956–62. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.4.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kelley MR, Kow YW, Wilson DM., 3rd Disparity between DNA base excision repair in yeast and mammals: translational implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:549–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hou EW, Prasad R, Asagoshi K, Masaoka A, Wilson SH. Comparative assessment of plasmid and oligonucleotide DNA substrates in measurement of in vitro base excision repair activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e112. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chastain PD, 2nd, Heffernan TP, Nevis KR, et al. Checkpoint regulation of replication dynamics in UV-irradiated human cells. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2160–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.18.3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Unsal-Kacmaz K, Chastain PD, Qu PP, et al. The human Tim/Tipin complex coordinates an Intra-S checkpoint response to UV that slows replication fork displacement. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3131–42. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02190-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Imlay JA, Linn S. DNA damage and oxygen radical toxicity. Science. 1988;240:1302–9. doi: 10.1126/science.3287616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dypbukt JM, Ankarcrona M, Burkitt M, et al. Different prooxidant levels stimulate growth, trigger apoptosis, or produce necrosis of insulin-secreting RINm5F cells. The role of intracellular polyamines. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30553–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lennon SV, Martin SJ, Cotter TG. Dose-dependent induction of apoptosis in human tumour cell lines by widely diverging stimuli. Cell Prolif. 1991;24:203–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1991.tb01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hampton MB, Orrenius S. Dual regulation of caspase activity by hydrogen peroxide: implications for apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 1997;414:552–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gregorini A, Tomasetti M, Cinti C, Colomba D, Colomba S. CD38 expression enhances sensitivity of lymphoma T and B cell lines to biochemical and receptor-mediated apoptosis. Cell Biol Int. 2006;30:727–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frossi B, Tell G, Spessotto P, Colombatti A, Vitale G, Pucillo C. H(2)O(2) induces translocation of APE/Ref-1 to mitochondria in the Raji B-cell line. J Cell Physiol. 2002;193:180–6. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DeMott MS, Beyret E, Wong D, et al. Covalent trapping of human DNA polymerase β by the oxidative DNA lesion 2-deoxyribonolactone. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7637–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Greenberg MM, Weledji YN, Kroeger KM, Kim J. In vitro replication and repair of DNA containing a C2′-oxidized abasic site. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15217–22. doi: 10.1021/bi048360c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sung JS, DeMott MS, Demple B. Long-patch base excision DNA repair of 2-deoxyribonolactone prevents the formation of DNA-protein cross-links with DNA polymerase β. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39095–103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506480200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Von Sonntag C. Polynucleotides and DNA. In: Sonntag CV, editor. The Chemical Basis of Radiation Biology. London: Taylor and Francis, Ltd; 1987. [Google Scholar]