Abstract

Caregivers of people living with HIV (PLH) in Thailand face tremendous caregiver burden. This study examines complex ways in which caregivers’ mental health affects their levels of caregiver burden. This study uses data from 409 caregivers of PLH in northern and north-eastern Thailand. Multiple regression models were used to examine the predictors of caregiver burden. Depression was significantly associated with caregiver burden (P < 0.0001) and being HIV positive (P = 0.015). Inverse associations were observed between depression and quality of life (P < 0.0001) and caregiver burden and quality of life (P = 0.004). Social support had direct positive association with caregiver’s quality of life (P < 0.0001). Our findings underscore the complex relationship between caregiver burden, depression and HIV-status. Interventions that address the caregiver burden are urgently needed.

Keywords: caregiver burden, HIV, Thailand

INTRODUCTION

In Thailand, the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy has dramatically altered the nature and duration of HIV/AIDS caregiving. Families play a significant role of support for people living with HIV (PLH) in Thailand. As the number of PLH increases, the demands of family caregivers who take on the sole responsibility for the care of PLH are growing. In addition to emphasis on the patient’s well-being, there is a growing body of evidence related to the outcomes of family caregivers. The care of PLH can place a significant burden on family caregivers.1

Within the context of families living with HIV, multiple factors contribute to caregiver burden. First, caregiving usually comes as an unexpected role, one for which caregivers are neither socialized nor prepared.2 In order to assume this unexpected new role, caregivers must restructure pre-existing role obligations and social activities and the ways in which they relate to PLH.2,3 Progressive increases in caregivers’ responsibilities over the course of HIV might require further adjustments in family, work and social commitments.4 The physical demands of caregiving also contribute significantly to burden. Unlike health-care workers, family caregivers often are ‘on call’ 24 h a day and might be required to perform multiple, and sometimes conflicting roles.5 Those who never cared for a seriously ill person must quickly learn basic nursing skills, often under extremely stressful circumstances.

Over the past decade, many studies have focused on the negative consequences of caregiving, generally referred to as caregiver burden,6 caregiver stress7 and caregiver strain.8 Recent qualitative studies in Thailand reported that caregivers of PLH felt overwhelmed with the caregiving demands in the care of their family members.9 Caregivers experienced enormous burdens related to inadequate resources and insufficient support. These findings underscore the importance of examining the effects of caregiver burden on family members of PLH.

Caregiver burden is a multidimensional phenomenon reflecting the physical, emotional, social and environmental consequences of caring for an impaired family member.10 The examination of caregiver burden is critical to service providers who work with families in communities. In addition, relatively few studies in Thailand have examined the multiple factors associated with caregiver burden, such as perceived social support, depression and caregiver’s quality of life.11 A better understanding of the multiple factors associated with caregiver burden can help inform providers to develop tailored programmes and specific interventions to assist HIV-affected families, addressing the needs of both the PLH and their caregivers.

The impact of caregiver burden on their mental health, physical health and social support in Thailand has not been well established. With a sample of 409 caregivers of PLH in northern and north-eastern Thailand, we examined correlations among mental health, quality of life, social support and caregiver burden as well as their relationships with demographic characteristics. In particular, we explored the ways in which caregivers’ mental health affect their level of caregiver burden, which in turn impacts their overall quality of life. Empirical evidence about the relationships between these factors will provide better understanding of these challenges facing caregivers of PLH in Thailand and scientific foundations for future intervention development tailored for PLH and their caregivers.

METHODS

Participants and setting

This study uses data from a randomized controlled family intervention trial in the northern and north-eastern regions of Thailand.12 These data were collected in 2007 from four district hospitals in the two regions (two district hospitals per region). Initial screenings of caregivers of PLH were conducted in the district hospitals and performed by health-care workers and research staff specifically hired for the study. Once the caregivers had been screened and had agreed to participate in the study, written informed consent was obtained. Following informed consent, a trained interviewer administered the assessment to family members of PLH using computer-assisted personal interview. During the interview, caregivers were asked about their demographics, including gender, age, educational status, employment status, marital status and annual income. Caregivers were asked about their quality of life, social support, mental health and the level of caregiver burden. A total of 408 caregivers voluntarily participated in the assessment. Refusal rate was ≈5% across the four study sites.

Approval of this study was obtained from Institutional Review Boards from the University of California at Los Angeles, and the Thailand Ministry of Public Health Ethical Review Committee for Research in Human Subjects. All participants received 300 bahts (equivalent to $10) for their assessment participation.

Measures

Quality of life was measured using the Thai version of the Short Form (26 items) of the WHO Quality of Life questionnaire.13 Each item is scored 1–5 on a response scale. The overall quality of life scale (26 items) has satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.82).

Depression was assessed with a 15-item depression screening test that was developed and used previously in Thailand.14 These questions asked about problems that had bothered participants in the past week (e.g. feeling blue most of the time, feelings of worthlessness, loss of self-confidence), with response categories from 0 (not at all) to 3 (usually (5–7 days a week)). A summative composite scale was developed, with the range of 0–45 and an excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.89).

Social support was constructed as a composite variable based on the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale.15 The social support scale included both emotional and informational support, measured by eight items, and affectionate support including three items. Responses to individual items ranged from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). We combined the two subscales because they were highly correlated to yield a composite scale with a satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.90). This summative composite score ranged from 11 to 55.

Caregiver burden was a 22-item scale adapted from the Caregiver Burden Scale.6 The items related to the changes family members must face in their everyday life and routines. Responses to individual items ranged from 0 (never) to nearly always (4). The scale composed of five domains to assess the level of burden among caregivers of PLH: (1) General feelings, (2) feelings regarding caring for PLH, (3) sense of responsibility, (4) feelings when with impaired PLH, and (5) impact of PLH on caregivers’ relationship. The adapted scale had a satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.82). This summative composite score ranged from 0 to 88.

Sociodemographic characteristics included: gender, age in years, education, employment status, marital status, income and HIV status.

Data analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). First, descriptive statistics were used to describe caregivers’ demographics, quality of life, mental health, social support and caregiver burden. Second, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the relationship between quality of life, mental health and social support, as well as demographic variables such as gender, age, education and income. Third, a series of multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine correlates of caregiver burden and caregiver quality of life, simultaneously controlling for caregivers’ gender, age, education, income and HIV status. Regression coefficients estimation (standardized beta) and their significant levels (P-values) are reported.

RESULTS

Table 1 describes the sociodemographic characteristics of the caregivers of PLH in the study. A majority of the sample, 66.6%, was female. About one-fourth of the caregivers in the study were also HIV positive (24.2%). Age ranged 19–80 years. The mean age of the participants was 44.3 years (standard deviation (SD) = 13.4). Most participants (86.6%) received less than high school education. A majority of the caregivers were employed (86.5%) and married/living with someone (79%). The average individual annual income was 31 805 bahts per year (equivalent to $908). The mean quality of life scale score was 89.9 (SD = 9.92). The mean depression and social support scores were 10.7 (SD = 7.25) and 36.7 (SD = 8.85), respectively. The mean caregiver burden score was 46.8 (SD = 12.12). A majority of the caregivers in the study reported either ‘moderate to severe’ or ‘severe’ burden (66.5%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of caregivers of people living with HIV (n = 409)

| Characteristics | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 271 | 66.6 |

| Male | 136 | 33.4 |

| HIV positive | 99 | 24.2 |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤ 30 | 50 | 12.3 |

| 31–40 | 145 | 35.6 |

| 41–50 | 90 | 22.1 |

| > 50 | 122 | 30.0 |

| Education | ||

| Less than elementary | 112 | 27.4 |

| Elementary/Junior | 242 | 59.2 |

| ≥ Some high school | 55 | 13.5 |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | 352 | 86.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/cohabit | 319 | 79.0 |

| Divorced/separated | 24 | 5.9 |

| Widowed | 47 | 11.6 |

| Never married | 14 | 3.5 |

| Personal income (bahts) | ||

| ≤ 15 000 | 124 | 30.6 |

| 15 001–35 000 | 97 | 24.0 |

| 35 001–55 000 | 85 | 21.0 |

| ≥ 55 001 | 99 | 24.4 |

| Mean | Standard deviation | |

| Quality of Life (Cronbach’s α = 0.82) | 89.9 | 9.92 |

| Depression (Cronbach’s α = 0.89) | 10.7 | 7.25 |

| Social support (Cronbach’s α = 0.90) | 36.7 | 8.85 |

| Caregiver burden (Cronbach’s α = 0.82) | 46.8 | 12.12 |

| Frequency | % | |

| Minimal burden | 1 | 0.24 |

| Mild to moderate burden | 136 | 33.25 |

| Moderate to severe burden | 217 | 53.06 |

| Severe burden | 55 | 13.45 |

The correlation coefficients among sociodemographic characteristics, quality of life, mental health, social support and caregiver burden are presented in Table 2. Quality of life was positively correlated with social support (correlation coefficient (r) = 0.48, P < 0.0001), and negatively correlated with depression (r = −0.39, P < 0.0001) and caregiver burden (r = −0.30, P < 0.0001). As expected, depression was negatively correlated with social support (r = −0.17, P < 0.05) and positively correlated with caregiver burden (r = 0.41, P < 0.0001). Caregiver burden was negatively correlated with social support (r = −0.15, P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients and significance levels across demographics, quality of life, mental health and caregiver burden

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Female | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Age | 0.09 | 1 | |||||||

| 3. Education | −0.08 | −0.38** | 1 | ||||||

| 4. Annual income | −0.19* | −0.17* | 0.26** | 1 | |||||

| 5. HIV positive | −0.26** | −0.34** | 0.06 | −0.05 | 1 | ||||

| 6. Quality of life | −0.08 | −0.21** | 0.22** | 0.13* | 0.10* | 1 | |||

| 7. Depression | 0.27** | 0.12* | −0.13* | −0.13* | −0.07 | −0.39** | 1 | ||

| 8. Social support | −0.01 | −0.26** | 0.31** | 0.18* | 0.07 | 0.48** | −0.17* | 1 | |

| 9. Caregiver burden | 0.07 | 0.13* | −0.16* | −0.16* | 0.07 | −0.30** | 0.41** | −0.15* | 1 |

P < 0.05.

P < 0.0001.

Significant correlations were also found among caregivers’ sociodemographic characteristics, and quality of life, mental health, social support and caregiver burden. For example, women reported higher depression (r = 0.27, P < 0.0001). Age was negatively correlated with quality of life (r = −0.21, P < 0.0001), social support (r = −0.26, P < 0.0001), and positively correlated with depression (r = 0.12, P < 0.05) and caregiver burden (r = 0.13, P < 0.05). Higher education was positively correlated with quality of life (r = 0.22, P < 0.0001), social support (r = 0.31, P < 0.0001), and negatively correlated with depression (r = −0.13, P < 0.05) and caregiver burden (r = −0.16, P < 0.05). Similarly, income was positively correlated with quality of life (r = 0.13, P < 0.05), social support (r = 0.18, P < 0.05), and negatively correlated with depression (r = −0.13, P < 0.05) and caregiver burden (r = −0.16, P < 0.05).

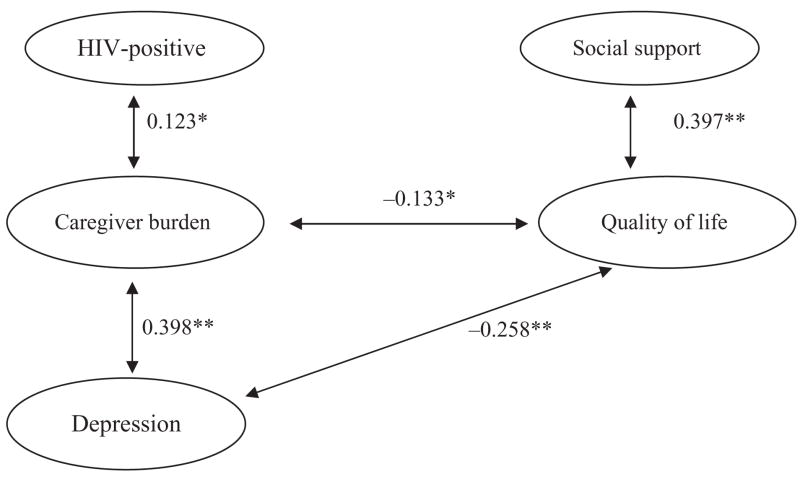

Figure 1 outlines the final model of the correlates of caregiver burden, and Table 3 outlines multiple regression models examining factors associated with depression, happiness and caregiver burden. Controlling for selected demographic characteristics (gender, age, education and income), higher levels of depression were significantly associated with higher levels of caregiver burden (standardized beta (β) = 0.398, P < 0.0001). We also observed a significant association between caregiver burden and being HIV positive (β = 0.123, P = 0.015). We also observed the complex relationship between depression, quality of life, and social support. Controlling for demographic characteristics, we observed a significant association between depression and quality of life (β = −0.258, P < 0.0001) and depression (β = −0.219, P = 0.004). In addition, we found significant positive associations between social support and quality of life (β = 0.397, P < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Final model of the correlates of caregiver burden and quality of life. Adjusted for gender, age, education and income. * P < 0.05. **P < 0.0001.

Table 3.

Multiple regression on caregiver burden and quality of life of caregivers of people living with HIV

| Caregiver burden |

Quality of life |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P-value | β | P-value | |

| Female | −0.036 | 0.467 | 0.025 | 0.583 |

| Age | 0.084 | 0.111 | −0.026 | 0.581 |

| Education | −0.059 | 0.248 | 0.032 | 0.491 |

| Annual income | −0.073 | 0.127 | 0.003 | 0.946 |

| HIV positive | 0.123 | 0.015 | 0.056 | 0.221 |

| Social support | −0.038 | 0.438 | 0.397 | <0.0001 |

| Caregiver burden | – | – | −0.133 | 0.004 |

| Depression | 0.398 | <0.0001 | −0.258 | <0.0001 |

= standardized beta coefficient.

DISCUSSION

In our study, we found a significant level of caregiver burden. Over 66% of the caregivers in this study reported experiencing ‘moderate to severe’ or ‘severe’ burden. Consistent with existing literature, we found that caregiving might have tremendous adverse effects on the psychological well-being of caregivers.16,17 The emotional stress on caregivers can be significant. The greater responsibility forces caregivers to stay emotionally and physically strong to support PLH.18 The demanding nature of caregiving for PLH means that caregivers can face social isolation.19 In addition, HIV infection among the caregivers can place additional strain on caregivers. The stresses of declining health and the added burden of taking care of PLH might contribute to psychological distress.20

We found that caregiver’s depression was strongly and independently associated with the level of caregiver burden. Our study finding is consistent with previous research, suggesting that depression is common among caregivers of those with other diseases. For instance, among caregivers of demented patients, more hours spent on caregiving were associated with depression in the caregiver.21 Our findings add to the body of literature regarding caregivers of PLH, particularly towards the observation of an association of depression and caregiver burden. Consistent with other studies,22,23 we also found that the HIV status of the caregiver was significantly associated with caregiver burden. Future HIV programmes should focus on the well-being of PLH while taking into account of the caregiver’s well-being. Our findings have significant implications on future HIV intervention programmes.

Our findings underscore the complex relationship between caregiver burden and their level of quality of life, happiness and social support. These multiple factors have complex relationships with their level of depression, which in turn influences caregivers’ level of burden. Further research is needed to examine the stress process of caregiving among HIV-affected families in Thailand. Our findings suggest that the context of HIV caregiving in Thailand might compound the social and psychological costs of caregiving in general. For example, social support might help mitigate stress effects of caregiving.24 However, at the time of intensive caregiving, the duty to take care of PLH might restrict social contact, with possible implications to caregivers’ access to network resources, psychological well-being and continuity of caregiving.25

As with all studies, there are some limitations to this study. First, we conducted data analyses based on baseline cross-sectional data; therefore, causal interpretations of the results cannot be established. For example, those caregivers reporting high levels of burden might also report high levels of depression; however, we cannot establish the causality path of the relationship. We can only suggest that depression and caregiver burden are associated. Second, the reliance on self-report measures might be susceptible to information bias.

Despite the limitations, our study findings have implications for future HIV intervention in Thailand. Programmes and intervention that address the challenges that PLH and their caregivers face are urgently needed. Longitudinal examination of the impact of the cumulative burden of caregiving on caregivers’ social support, psychological well-being and quality of life might contribute to a better understanding of service providers’ capacities to respond to the needs of families living with HIV in Thailand. The programmes should address the mental health needs of caregivers and the level of burden the caregivers are experiencing while taking care of PLH. Understanding the complex relationship between caregiving, social support, mental health and quality of life might help to identify effective approaches to intervention to promote HIV caregiving, its potential positive effects on the well-being of PLH, and minimize the level of burden experienced by the caregivers. Building on the existing programmes in Thailand, we are currently mounting a longitudinal trial and providing the family-based intervention for PLH and their caregivers in northern and northeastern Thailand, focusing on family well-being, in a non-stigmatizing setting.

Acknowledgments

This paper was completed with the support of the National Institute of Nursing Research (Grant NINR R01-NR009922). We thank our research coordinators, hospital directors and health officers in Chiang Rai province (Mae Chan and Chiang Saen district hospitals) and Nakhon Ratchasima province (Pak Chong and Khonburi district hospitals). We thank our collaborators at the Thai Ministry of Public Health, Bureau of Epidemiology for their contributions to the study.

Contributor Information

Sung-Jae Lee, Research Epidemiologist, University of California, Semel Institute Center for Community Health, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Li Li, Research Sociologist, University of California, Semel Institute Center for Community Health, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Chuleeporn Jiraphongsa, Chief of Field Epidemiology Training Program, Thai Ministry of Public Health, Bureau of Epidemiology, Bangkok, Thailand.

Mary J Rotheram-Borus, Professor, University of California, Semel Institute Center for Community Health, Los Angeles, California, USA.

References

- 1.Turner HA, Catania JA, Gagnon J. The prevalence of informal caregiving to persons with AIDS in the United Statues: Caregiver characteristics and their implications. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;38:1543–1552. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearlin LI, Aneshensel CS, LeBlanc AJ. The forms and mechanisms of stress proliferation: The care of AIDS caregivers. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:223–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown MA, Powell-Cope GM. Caring for A Loved One with AIDS: The Experiences of Families, Lovers, and Friends. Seattle, WA, USA: University of Washington Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raveis VH, Siegel K. AIDS Patient Care. 1991. The impact of care giving on informal or familial care givers; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Neill JF, McKinney MM. [Accessed 21 February 2009.];A Clinical Guide to Supportive & Palliative Care for HIV/AIDS 2003 Edition. Chapter 20. Care for the Caregiver. Available from URL: http://hab.hrsa.gov/tools/palliative/chap20.html.

- 6.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the Impaired Elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20:649–655. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple S, Skaff MM. Caregiving and stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Given CW, Given B, Stommel M, Collins C, King S, Franklin S. The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Research in Nursing and Health. 1992;15:271–283. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770150406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phengjard J, Brown MA, Swansen KM, Schepp KG. Family caregiving of persons living with HIV/AIDS in urban Thailand. Thai Journal of Nursing Research. 2002;6:87–100. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Aneshensel CS, Wardlaw L, Harrington C. The structure and functions of AIDS caregiving relationships. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1994;17:51–67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pirraglia PA, Bishop D, Herman DS, et al. Caregiver burden and depression among informal caregivers of HIV-infected individuals. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20:510–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li L, Lee SJ, Thammawijaya P, Jiraphongsa C, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Stigma, social support, and depression among people living with HIV in Thailand. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1007–1013. doi: 10.1080/09540120802614358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. [Accessed 21 April 2009.];The World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (Thai) 2004 Available from URL: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/en/thai_whoqol.pdf.

- 14.Thai Department of Mental Health. Depression screening test. Ministry of Public Health; Thailand: 2004. [Accessed 12 May 2009.]. Available from URL: http://www.dmh.go.th/test/depress/asheet.asp?qid=1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Social Science Medicine. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeBlanc AJ, London SS, Aneshensel CS. The physical costs of AIDS caregiving. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;45:915–923. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minkler K, Fuller-Thomson E. The health of grandparents raising grandchildren: Results of a national study. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1384–1389. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knodel J, VanLandingham M, Saengtienchai C, Imem W. Older people and AIDS: Quantitative evidence of impact in Thailand. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;52:1313–1327. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reddy P, Shegs J, Esu-Williams E, Fisher A. ‘ “Inkala Ixinge Etyeni: Trapped in A Difficult Situation”: The Burden of Care on the Elderly in the Eastern Cape, South Africa,’ Horizons Research Update. Johannesburg, South Africa: Population Council; 2005. [Accessed 22 March 2009.]. Available at URL: http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/horizons/saeldrcrgvrru.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wight RG. Precursive depression among HIV-infected AIDS caregivers over time. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51:759–770. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Covinsky KE, Newcomer R, Fox P, et al. Patient and caregiver charateristics associated with depression in caregivers of patients with dementia. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18:1006–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.30103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Land H, Hudson SM, Stiefel B. Stress and depression among HIV-positive and HIV-negative gay and bisexual AIDS caregivers. AIDS and Behavior. 2003;7:41–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1022509306761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folkman SM, Chesney MA, Cooke M, Boccellari A, Collette L. Caregiver burden in HIV-positive and HIV-negative partners of men with AIDS. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:746–756. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demi A, Bajeman R, Moneyhan L, Sowell R, Seals B. Effects of resources and stressors on burden and depression of family members who provide care to an HIV-infecetd woman. Jounral of Family Psychology. 1997;11:35–48. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aneshensel CS, Pearlin LI, Schuler RH. Stress, role captivity, and cessation of caregiving. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1993;34:54–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]