Abstract

Orthotopic liver transplantation in mice and rats is used to study a wide range of scientific questions. Inhalant anesthesia is widely used in liver transplantation models in rodents, but drawbacks of inhalant anesthetics include issues of cost, safety, and ease of use. The goal here was to find an effective injection anesthesia protocol that would not directly influence metabolic or functional parameters after liver transplantation. We compared intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine–xylazine–acepromazine cocktail (KXA) with isoflurane during 50% liver transplantation in mice and rats. Anesthesia with KXA had rapid induction (5 ± 3 min) and a long duration of surgical anesthesia (70 ± 10 min). The 2 methods of anesthesia produced no significant differences in liver injury (histology, serum alanine aminotransferase and total bilirubin concentrations), inflammation (IL6, TNFα, myeloperoxidase activity), regeneration (incorporation of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine, mitotic index, restitution of liver weight), or 7-d survival. In conclusion, a KXA regimen is a safe and effective injectable anesthetic for rodent liver transplantation and is a suitable substitute for currently used inhalant anesthesia. Injectable anesthetics offer advantages in terms of cost, personal safety, and ease of use and will be particularly beneficial to microsurgeons during their training period in liver transplantation.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BrdU, 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine; KXA, ketamine–xylazine–acepromazine combination

Liver transplantation in rats or mice is a difficult and complex procedure requiring delicate surgery and stable, effective anesthesia for an extended period. The liver is the major organ for drug metabolism and is thus susceptible to toxic injury induced by many anesthetics and analgesics that undergo hepatic metabolism. Inhalant anesthetics, and isoflurane in particular, represent the current standard for anesthesia in rodent liver transplantation due to their low hepatotoxicity and the fact that they primarily are excreted by exhalation.2,3 Inhalant anesthesia has many advantages: depth of anesthesia is easy to control; the drugs require minimal metabolism, biotransformation, and excretion; and decreased cardiopulmonary depression results in improved safety and decreased recovery time.4 However, the use of inhalant anesthesia offers several drawbacks. For example, the use of either ether or isoflurane can result in undue exposure of investigators, requires additional specific devices (such as hoods, nose cones, oxygen flow system, vaporizer, circuits, valves, scavenging canisters), and is expensive. In contrast, anesthesia using injectable agents can be inexpensive, easier to perform, and have considerable benefits with regard to personnel health, given that investigators are not exposed to the potential adverse effects of vapors. Furthermore, manipulating animal position is easier after injectable than inhalant anesthesia, especially when working in a biological safety cabinet in barrier facilities. Perhaps most importantly, we have found that during the training period for rodent liver transplantation, more than 1/3 of animal deaths are related to incorrect handling of inhalation anesthesia, thus providing the impetus for this study.

The method of anesthesia can influence metabolic and functional parameters associated with surgical procedures. The goal of the current study was to develop an injectable anesthesia protocol that would be well tolerated by rodents and that would not directly influence metabolic or functional parameters after liver transplantation. An ideal candidate drug for liver transplant surgery would have minimal effect on liver function and have a long halflife (providing a surgical tolerance of at least 60 min). Few current monoanesthetics meet these criteria, and although the use of pentobarbital injection in liver transplantation has been reported,19 other studies22 and our unpublished data show that pentobarbital injection is associated with high (greater than 40%) mortality.

The practice of ‘balanced anesthesia’ has been recommended in veterinary medicine.4 Balanced anesthesia is the administration of a mixture of sedatives, analgesics, and anesthetics to produce anesthesia with lower doses than would be necessary if each component were used individually. This practice has the advantage of synergy and avoids the unwanted effects caused by a high dose of an individual drug. A balanced anesthetic combination used for rodents is ketamine, xylazine, and acepromazine (KXA). Ketamine is metabolized extensively by hepatic microsomal enzyme systems, and most of a dose of ketamine is excreted in the urine as hydroxylated and conjugated metabolites.7 Ketamine usually is used in combination with the α2 agonist xylazine, which also undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism and is excreted in the urine. Several reports indicate that ketamine–xylazine at recommended doses does not provide a surgical plane of anesthesia in mice due to a short halflife.4 Acepromazine is a phenothiazine tranquilizer and has a slow elimination rate. Like ketamine and xylazine, acepromazine is metabolized in the liver and eliminated in the urine. A previous study1 investigated several intraperitoneal injection anesthesia protocols and found that the KXA combination was effective for medium-duration mouse anesthesia, and a similar protocol has been used previously in BALB/c mice and rats.4,33 In the present study, we compared the use of inhalant anesthesia (isoflurane) with a KXA injectable anesthetic regimen during small-for-size liver transplantation in mice and rats. We examined the effects of anesthesia on liver function, pathologic change, liver regeneration, and survival—parameters widely used to assess outcome after liver transplantation. Our results suggest that the use of KXA is a safe and effective injectable anesthesia protocol for liver transplantation in rodents and that it is an acceptable substitute for inhalant anesthesia.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals.

The study population comprised wild-type C57BL/6 male mice (age, 8 to 10 wk; weight, 20 to 25 g; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and male Lewis rats (approximate age, 10 wk; weight, 200 to 225 g, Charles River, Wilmington, MA). All animals were specific-pathogen-free and kept in a temperature-controlled environment in a ventilated rack with a 12:12-h light:dark cycle. Food and water were given ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the Medical University of South Carolina Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.12

Anesthesia protocol.

Animals were allocated randomly into 2 groups, each of which consisted of 12 animals that underwent 1 of 2 anesthetic procedures (injectable KXA or inhalant isoflurane), half as recipient and the other half as donor. An additional 10 pairs of mice and 20 pairs of rats in each anesthetic group were used for 7-d survival observation. For isoflurane anesthesia, animals were anesthetized by using an automatic delivery system (Isoflurane Vaporizer, Vaporizer Sales and Services, Rockmart, GA) that provides a mixture of isoflurane and oxygen. Animals in the KXA cohort were anesthetized through intraperitoneal injection of a cocktail containing ketamine (65 mg/kg), xylazine (13 mg/kg), and acepromazine (1.5 mg/kg) in sterile normal saline. For anesthesia with KXA, a single dose was administered with inflow of 100% oxygen at 2 L/min during surgery only, whereas isoflurane was administered by nose cone continuously. The inflow of isoflurane needed to be adjusted during different operation periods (3% in induction phase, 2% in hepatic phase of transplantation, and less than 0.5% in anhepatic phase). The anesthesia protocol was the same for mice and rats.

Anesthetic induction and anesthetic depth was assessed by a scoring system as previously described.4 Surgical tolerance was defined as lack of response to a tactile stimulus and absent or delayed pedal withdrawal reflex response. Immobilization time was defined as the duration of no movement of animals during anesthesia. Sleeping was defined as no movement but responsive to stimuli after anesthesia.

After anesthesia and surgery, all animals were allowed to spontaneously breathe room air and were placed on an electric heating blanket under a warming light. As approved by the institutional animal care and use committee, analgesics were not used, given that they modify the inflammatory response9,23,24,32 and thus perhaps affect the parameters under study here. However, to minimize discomfort, in the event of severe distress, selfmutilation, infection (persistent swelling, redness, pus at incision site), or acute pain (demonstrated by vocalization, restlessness, lack of mobility, failure to groom, abnormal posture, and lack of normal interest in surroundings), animals were euthanized by KXA overdose followed by cervical dislocation.

50% liver transplantation model.

Mouse orthotopic 50% small-for-size liver transplantation was performed as previously described.5,31 Briefly, for donor operations, the pyloric vein, right adrenal veins, and renal arteries and veins were ligated and severed. The gallbladder was removed after ligature of the cystic duct. Common bile duct was cannulated with polytetrafluoroethylene tubing (inner diameter, 0.2 mm) and divided. After portal infusion of cold (0 to 4 °C) UW solution (3 mL; 100 mM potassium lactobionate, 25 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM MgSO4, 5 mM adenosine, 3 mM glutathione, 1 mM allopurinol, 50 g/L hydroxyethyl starch), the 50% grafts were obtained by removal of the left lateral lobe, caudate lobe, and left portion of the median lobe. Cuffs were placed on the portal veins and subhepatic inferior vena cava by using 20- and 18-gauge intravenous catheters, respectively (Braun Medical, Bethlehem, PA). Excised livers were immersed in cold (0 to 4 °C) UW solution inside glass containers and stored for 2 h until implantation. The time for the donor procedure averaged 30 min.

During the recipient surgery, livers of recipient mice were removed after dividing the bile duct at the hilum and clamping and dividing the suprahepatic inferior cava, portal vein, and subhepatic inferior cava. Cold-stored (2 h) donor livers then were implanted by anastomosing the suprahepatic vena cava with a running 10-0 nylon suture and connecting the portal veins and infrahepatic vena cava by cuff insertion. Bile ducts were anastomosed over polytetrafluoroethylene stents. The abdomen was closed with a continuous 6-0 polypropylene suture. The recipient operation averaged 45 min, and the portal vein clamp time averaged 15 min. For the sham operation, mice were anesthetized, and the ligaments around the liver were dissected without transplantation. Fifty minutes later, the abdominal wall was closed with a running suture.

Small-for-size (50%) liver orthotopic transplantation in rats was performed as described previously.21 Briefly, rats were anesthetized, the left portion of the median lobe and the left lateral lobe were removed after ligation with 5-0 suture, and then the liver was explanted. Cuffs were placed on the portal veins and subhepatic inferior vena cava by using 14-gauge intravenous catheters. Reduced-size liver explants were weighed and stored in UW solution at 0 to 4 °C for 2 h. The time for the donor procedure averaged 25 min. For implantation, the small-size grafts were transplanted into inbred rats matched for body weight by using a 2-cuff method after removal of the native liver. The recipient operation averaged 50 min, and the portal vein clamp time averaged 12 min.

Blood samples (about 40 µL from individual mice and 100 µL from rats) were collected at 24 h after surgery from the tail vein (mice) or by the saphenous venipuncture method (rats) without anesthesia as previously described.20 Animals were euthanized 48 h after surgery, and blood and liver samples were harvested. Serum was obtained by centrifugation and stored at –80 °C. Livers were weighed to assess the degree of regeneration. Portions of the liver tissue were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histologic evaluation or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and maintained at –80 °C until homogenization for biochemical assays.

Histologic examination.

Samples of liver tissue were placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48 h before being embedded in paraffin for preparation of tissue blocks. Liver histology was assessed by light microscopy of sections (thickness, 4 µm) stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and necrosis and liver injury were scored in a blinded fashion as described.28

Serum alanine aminotransferase and total bilirubin.

To assess alanine aminotransferase (ALT) release and accumulation of total bilirubin due to liver injury, postoperative blood samples were collected from the tail vein at 24 h and the vena cava at 48 h after surgery. Serum was obtained by centrifugation and stored at –80 °C. ALT activity and total bilirubin were determined using analytical kits from Sigma Chemical (St Louis, MO).

Assessment of liver regeneration.

Three independent markers for hepatic regeneration were measured. Restitution of liver weight was expressed as percentage of regenerated liver mass relative to total liver weight according to the formula

where A is the total liver weight at the time of partial hepatectomy, B equals the weight of resected liver, and C is the weight of the liver at euthanasia. For assessment of hepatic proliferation, 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU) was injected (50 mg/kg IP) 2 h prior to harvesting of liver. BrdU incorporation in liver sections was determined by immunohistochemical staining (described following). The mitotic index was determined in sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin by using previously reported criteria for mitosis.7 The mitotic index was expressed as the rate of positive cells per 1000 hepatocytes in 1 high-power (magnification, ×400) field. All analyses were performed by an evaluator who was blind to experimental group.

Immunohistochemical staining for BrdU.

Liver sections were deparaffinized with xylene (Mallinckrodt Baker, Paris, KY) and rehydrated through a graded series of ethanol–water mixtures. To retrieve antigen, sections were incubated with 4 N HCl for 20 min and then incubated with pepsin reagent (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) at 37 °C for 15 min. Sections were exposed to mouse antiBrdU monoclonal antibodies (dilution, 1:200, Sigma, St. Louis, MO.) in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.1) containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 1% bovine albumin (Sigma) for 10 min at room temperature. Peroxidase-conjugated antimouse IgG1 antibody (Dako) was applied, and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine chromagen was added as the peroxidase substrate. A light counterstain of modified Mayer hematoxylin (American Master Tech Scientific, Lodi, CA) was applied so that unlabeled nuclei could be identified easily. Positive and negative cells were counted in 10 randomly selected fields under light microscopy (magnification, ×400). Constantly proliferating intestinal crypt epithelium from small intestine served as a positive control for BrdU incorporation and staining.

Measurement of cytokines and myeloperoxidase.

Serum concentrations of TNFα and IL6 at 48 h after surgery were measured by using commercially available ELISA kits (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Myeloperoxidase in homogenized liver was measured using a commercially available ELISA kit (Mouse MPO ELISA Kit, Hycult Biotechnology, Uden, Netherlands). Liver tissue was homogenized in 200 µL lysis buffer (200 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris, 10% glycine, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluroide, 1 µg/mL leupeptin, and 28 µg/mL aprotinin; pH 7.4). After centrifugation twice for 15 min at 1500 × g, 4 °C to remove cell debris, the supernatant was stored at –80 °C until assayed.

Statistical analysis.

Commercially available software GraphPad Prism 4.0 (Prism 4 for Windows, GraphPad prism, La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical evaluation. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. We used ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for groups with continuous multiple variables, and the Student t test was used for the comparison of a normally distributed continuous variable between 2 groups. For the survival study, Kaplan–Meier log-rank analysis was performed. All differences were considered statistically significant at a P value of less than 0.05.

Results

Anesthetic efficacy.

There were no significant differences in any measured parameter between the 2 sham operation groups that underwent different anesthesia, and only data from the KXA group is presented. Relative graft sizes in the different anesthesia groups were as follows: 45.6% ± 3.2% in the isoflurane group, and 46.3% ± 3.8% in the KXA group (P > 0.05 for both groups). Unless otherwise stated, the results presented below were obtained by using the mouse model of liver transplantation. Similar results were obtained with rat. The final paragraph of the Results section provides a summary of the rat data.

All mice recovered from anesthesia. Depth and quality of anesthesia (surgical tolerance) was characterized by the use of reflex tests, observation, and response to stimuli, and animals in both groups reached good surgical tolerance (defined as forelimb or hindlimb pedal withdrawal reflex scores greater than or equal to 3 and a tactile stimulus score of 4, as previously described 4). The induction time (mean ± SEM) was 5 ± 3 min in the KXA group, and 2 ± 0.5 min in isoflurane group. Animals in the isoflurane groups required careful handling to maintain the integrity of the anesthesia set-up (see Discussion). The time required to awaken from anesthesia differed significantly (P < 0.01) between the KXA- and isoflurane-treated mice. For the KXA group, the duration of surgical anesthesia was 70 ± 10 min, immobilization time was 130 ± 15 min, and sleeping time was 160 ± 25 min. In contrast, animals anesthetized with isoflurane rapidly awakened from anesthesia (6.9 ± 3.6 min).

Hepatic pathologic changes.

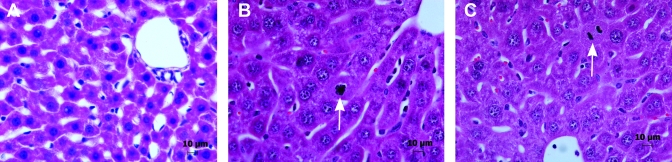

Livers were harvested for histology 48 h after implantation, at which point those from sham-treated mice showed no pathologic changes (Figure 1 A). Compared with livers in sham-operated mice, small-for-size grafts from both anesthesia groups displayed abnormal histology associated with liver damage and regeneration. The most prominent difference was mild focal necrosis that developed mainly in the periportal and midzonal regions of the liver lobule. Leukocytes infiltrated regions adjacent to necrotic areas. In addition, hepatocytes from grafts showed increased nuclear diameter and more numerous mitotic figures compared with livers from the sham group (P < 0.01). However, the 2 anesthetic groups showed no obvious histologic differences in grafts (Figure 1 B, C).

Figure 1.

Histologic examination of graft 48 h after 50% liver transplantation in mice. (A) Sham control. (B) Mouse anesthetized with KXA. (C) Mouse anesthetized with isoflurane. Liver collected from the sham control showed no changes histologically. Liver grafts from mice anesthetized with either KXA or isoflurane exhibited a moderate and similar level of damage, characterized by sinusoidal congestion and minimal necrosis, and a similar regenerative response characterized by increased nuclear diameter and numerous mitotic figures (white arrows). Each panel is a representative image from among the 6 animals in each group.

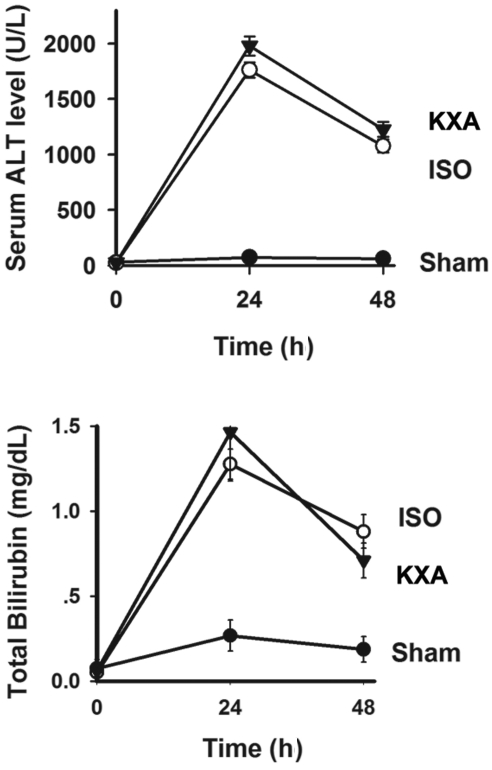

Liver function.

We examined the degree of hepatic damage and dysfunction by measuring ALT and total bilirubin levels. Both serum ALT and total bilirubin were increased significantly (P < 0.01 for both) at 24 and 48 h after implantation in recipients of small-for-size grafts compared with animals in the sham group (Figure 2). Neither ALT nor total bilirubin levels differed between recipients receiving isoflurane or KXA anesthesia.

Figure 2.

Serum levels of ALT and total bilirubin after mouse liver transplantation. Blood samples were collected from recipient mice anesthetized with either KXA or isoflurane (ISO) at 24 and 48 h posttransplantation of 50% liver grafts. Samples were assayed for (A) ALT and (B) total bilirubin. Baseline levels (mean ± SEM, n = 6) for ALT and total bilirubin were 28.67 ± 6.35 U/L and 0.07 ± 0.05 mg/L, respectively. Data from both anesthesia groups differed (P < 0.01 for both) from those from the sham group.

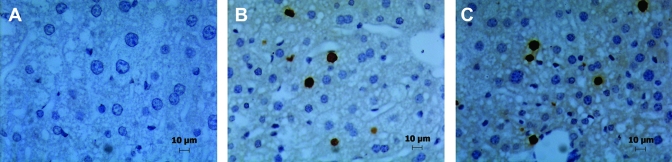

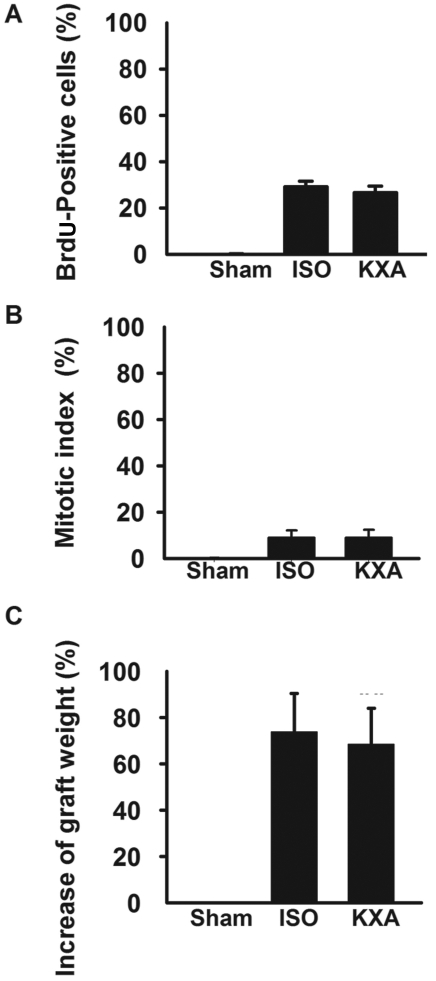

Graft liver regeneration.

Liver regeneration of small-for-size grafts was evaluated at 48 h after transplantation by BrdU staining, mitotic index, and graft weight. The hepatic proliferative response was evaluated by BrdU incorporation which was significantly higher in grafts than in livers from sham-operated mice (Figures 3 and 4 A). However, BrdU incorporation did not differ between the 2 anesthesia groups. The 2 anesthesia groups were not different with regard to mitotic index (the proportion of hepatocytes undergoing mitosis; Figure 4 B) or graft weight after transplantation (Figure 4 C).

Figure 3.

Incorporation of BrdU in mouse liver grafts harvested 48 h after implantation. BrdU (50 mg/kg, IP) was injected 2 h before harvest, and BrdU incorporation detected immunohistologically. Liver sections from (A) sham group, (B) isoflurane (ISO)-anesthetized group, and (C) KXA-anesthetized animals. Each panel is a representative image from among the 6 animals in each group

Figure 4.

Measurement of liver graft regeneration in mice. (A) Quantification of BrdU incorporation. (B) Increase in graft weight. (C) Mitotic index. Data are given as mean ± SEM (n = 6) for all analyses. None of the measured parameters of liver regeneration differed significantly between the KXA- and isoflurane (ISO)-anesthetized groups.

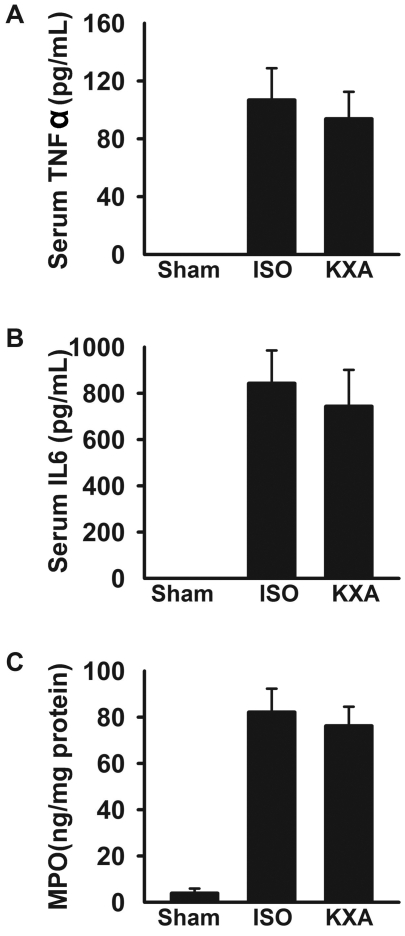

Inflammatory response after transplantation.

Serum levels of TNFα and IL6 at 48 h after transplantation were undetectable in sham-operated mice but were significantly increased (P < 0.01 for both) in recipients of small-for-size grafts. However, TNFα and IL6 levels did not differ between the mice in the 2 anesthesia groups (Figure 5 A). In addition, myeloperoxidase levels in livers from recipient mice were increased (P < 0.01 for both) compared with those in sham controls but again did not differ between the isoflurane- and KXA-anesthetized groups (Figure 5 B).

Figure 5.

Inflammatory response after small-for-size liver transplantation in mice. Hepatic inflammation as defined by serum concentrations (mean ± SEM, n = 6) of (A) TNFα, (B) IL6, and (C) hepatic myeloperoxidase (MPO) was measured by ELISA. None of the measured parameters of inflammation differed significantly between the KXA- and isoflurane (ISO)-anesthetized groups.

Mortality and morbidity of the animal.

Regardless of whether they received isoflurane or KXA anesthesia, none of the mice in the sham-operated group died. However 3 of the 10 mice in the KXA group died: 1 mouse at about 24 h, and 2 mice during the 2nd day after operation. All deaths occurred after the mice had fully recovered from anesthesia, and the animals that died did not appear to be in any distress prior to death. Of the 10 mice anesthetized with isoflurane, 2 died on day 2 after implantation. Log-rank analysis of the 7-d survival curves demonstrated no significant difference (P > 0.05) between the 2 anesthesia groups.

Rat model of small-for-size liver transplantation.

We also compared isoflurane and KXA anesthesia in a rat model of 50% liver transplantation. As with the mouse model, none of the postoperative measurements of liver function, injury, regeneration, or graft survival in rats differed between the 2 methods of anesthesia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Liver function, liver regeneration, and survival after 50% liver transplantation in rats

| ISO | KXA | |

| ALT (U/L) | 493 ± 73 | 526 ± 66 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.08 ± 0.67 | 0.96 ± 0.53 |

| BrdU-positive cells (%) | 31 ± 5 | 29 ± 6 |

| Increase of graft weight (%) | 55 ± 6 | 52 ± 5 |

| Survival (%) on day 7 (n = 20) | 90% | 85% |

Samples for ALT, total bilirubin, BrdU incorporation, and graft weight were collected 48 h after surgery from 6 rats each. Data are given as mean ± SEM.

None of the parameters differed significantly between anesthesia groups.

Discussion

Anesthesia, especially for prolonged periods, can be a considerable challenge, and the choice of anesthetic regimen depends on the type of study as well as the age, sex, and size of the animal species. Orthotopic liver transplantation in mice and rats are important research models, but the procedure is complex, technically demanding, and time-consuming. To date, inhalant anesthesia has been the only method widely used in rodent liver transplantation because of advantages of low mortality, quick and easy adaptation of the individual dose under routine laboratory conditions, and the possibility of extending the anesthetic period with low increased risk. However, serious risks and drawbacks are associated with inhalant anesthesia. For example, its application is complicated and requires expensive equipment; movement of animals as required for surgical intervention can be difficult, and there are potential health risks to investigators resulting from possible exposure to waste gases. Moreover, animals undergoing inhalation anesthesia must be monitored and anesthesia closely modulated to ensure that anesthesia is neither too deep (risk of death) nor too light (animals move or experience pain during the procedure). In addition, inflow of isoflurane must be modulated during the various phases of orthotopic liver transplantation surgery (for example, a low inflow of isoflurane is required during anhepatic phase).

In a previous report,1 8 intraperitoneal injection anesthesia protocols were compared for safety and efficacy for medium-duration murine surgery. The optimal regimen consisted of a combination of ketamine (dissociative anesthetic), xylazine (α2 agonist), and acepromazine (sedative); we used a similar anesthesia protocol here during liver transplantation in mice and rats. The method of anesthesia can influence metabolic or functional parameters after liver transplantation, and in a previous unpublished study, we found that liver regenerative capacity was severely impaired by pentobarbital sodium anesthesia (60 mg/kg IP) compared with isoflurane anesthesia in a model of 70% partial hepatectomy. Therefore in the present, we compared the effect of KXA anesthesia with isoflurane anesthesia (the current standard) on liver injury and regenerative capacity after 50% small-for-size transplantation. Our results show there was no difference between the 2 types of anesthesia with regard to graft function, hepatic regenerative capacity, or survival. Of further note, in the study mentioned previously,1 the reported time of surgical tolerance for a KXA regimen was 54 min. However, the time of surgical tolerance in our mouse liver transplantation model was 70 min, due to the anhepatic phase of liver transplantation, thus providing a window of time sufficient to complete the surgery. Another advantage of anesthesia with KXA is that, compared with isoflurane anesthesia, there is better relaxation of skeletal muscles, which enables better exposure of organs. Further, isoflurane anesthesia actually increased the surgery time due to the required adjustments to isoflurane inflow during the procedure and to increased difficulty in manipulating animal position during surgery (data not shown).

Previous studies have demonstrated that isoflurane anesthesia can have antiinflammatory effects and provide protection in some models.8,10,14,17,18 Furthermore, monoanesthesia with ketamine has been shown to be protective with regard to cardiovascular functions.6,13,15,20,25-27,30,34 In a swine model of hemorrhagic shock, a comparison of ketamine and isoflurane anesthesia demonstrated significantly decreased TNFα levels and less cardiovascular depressive effects in ketamine-anesthetized animals.6 In other studies, ketamine has been shown to suppress the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL6, and IL1.11,13,16,26 In another report,29 ketamine had hepatoprotective effects, whereas isoflurane does not. Using a rat LPS-induced model of liver injury, the authors demonstrated that ketamine attenuated endotoxin-attributable liver injury through a reduction in cyclooxygenase 2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase protein that was regulated through changes in NFκB-binding activity. In addition, in a rat burn model, anesthesia with ketamine decreased mortality and improved hepatoprotective effects, compared with isoflurane.20 However, as we show in the current study, there were no significant differences in several markers of inflammation, including TNFα, IL6, and myeloperoxidase activity, between KXA- and isoflurane-induced anesthesia.

In our current studies, no animal death was uniquely attributable to anesthesia, but the long postoperative recovery time should be emphasized. The animals are immobilized for more than 2 h and sleep for about 3 h after surgery, and although this course is energy-conserving, the animals need to be closely monitored. The relatively long recovery time can be considered a shortcoming of injection anesthesia, but importantly there were no significant differences compared with isoflurane anesthesia in any of the measured outcomes after liver transplantation.

The impetus for this study was the high animal mortality that we experienced when using inhalation anesthetic (both isoflurane and ether) during training. The control and monitoring of isoflurane anesthesia can be particularly difficult for microsurgeons early during the training period for liver transplantation. Surgical training can take 6 to 12 mo, and stable, safe, easy to use, and effective anesthesia is important not only for the health of the investigator but also greatly facilitates training. Indeed, in our experience, at least 1/3 of animals die in the early training period due to reasons related to incorrect depth of anesthesia. Injection of an anesthetic is a simpler alternative to inhalant anesthesia. The surgeon need not be distracted by anesthesia during the surgical period, and it safer than inhalant anesthesia with regard the health of the surgeon. We have found that KXA anesthesia can shorten the training period from between 6 to 12 mo to between 3 to 6 mo.

In conclusion, the injection protocol of KXA is a reasonable substitute for inhalant anesthetics anesthesia and offers several advantages in terms of cost, personal safety, and ease of use. The KXA regimen likely will be particularly beneficial to microsurgeons during their training period of liver transplantation in rodent models.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant RO1 86562 from the NIH (Bethesda, MD) and The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30972797).

References

- 1.Arras M, Autenried P, Rettich A, Spaeni D, Rulicke T. 2001. Optimization of intraperitoneal injection anesthesia in mice: drugs, dosages, adverse effects, and anesthesia depth. Comp Med 51:443–456 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asokan R, Hua J, Young KA, Gould HJ, Hannan JP, Kraus DM, Szakonyi G, Grundy GJ, Chen XS, Crow MK, Holers VM. 2006. Characterization of human complement receptor type 2 (CR2/CD21) as a receptor for IFNα: a potential role in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol 177:383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bovill JG. 2008. Inhalation anaesthesia: from diethyl ether to xenon. Handb Exp Pharmacol 182:121–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buitrago S, Martin TE, Tetens-Woodring J, Belicha-Villanueva A, Wilding GE. 2008. Safety and efficacy of various combinations of injectable anesthetics in BALB/c mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 47:11–17 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conzelmann LO, Zhong Z, Bunzendahl H, Wheeler MD, Lemasters JJ. 2003. Reduced-size liver transplantation in the mouse. Transplantation 76:496–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Englehart MS, Allison CE, Tieu BH, Kiraly LN, Underwood SA, Muller PJ, Differding JA, Sawai RS, Karahan A, Schreiber MA. 2008. Ketamine-based total intravenous anesthesia versus isoflurane anesthesia in a swine model of hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma 65:901–908, discussion 908–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fabrikant JI. 1968. The kinetics of cellular proliferation in regenerating liver. J Cell Biol 36:551–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flondor M, Hofstetter C, Boost KA, Betz C, Homann M, Zwissler B. 2008. Isoflurane inhalation after induction of endotoxemia in rats attenuates the systemic cytokine response. Eur Surg Res 40:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon SM. 2007. Translating science into the art of acute pain management. Compend Contin Educ Dent 28: 248–260; quiz 261, 282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helmy SA, Al-Attiyah RJ. 2000. The effect of halothane and isoflurane on plasma cytokine levels. Anaesthesia 55:904–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill GE, Anderson JL, Lyden ER. 1998. Ketamine inhibits the proinflammatory cytokine-induced reduction of cardiac intracellular cAMP accumulation. Anesth Analg 87:1015–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources 1996. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawasaki T, Ogata M, Kawasaki C, Ogata J, Inoue Y, Shigematsu A. 1999. Ketamine suppresses proinflammatory cytokine production in human whole blood in vitro. Anesth Analg 89:665–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ke JJ, Zhan J, Feng XB, Wu Y, Rao Y, Wang YL. 2008. A comparison of the effect of total intravenous anaesthesia with propofol and remifentanil and inhalational anaesthesia with isoflurane on the release of pro- and antiinflammatory cytokines in patients undergoing open cholecystectomy. Anaesth Intensive Care 36:74–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koga K, Ogata M, Takenaka I, Matsumoto T, Shigematsu A. 1994. Ketamine suppresses tumor necrosis factor α activity and mortality in carrageenan-sensitized endotoxin shock model. Circ Shock 44:160–168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsen B, Hoff G, Wilhelm W, Buchinger H, Wanner GA, Bauer M. 1998. Effect of intravenous anesthetics on spontaneous and endotoxin-stimulated cytokine response in cultured human whole blood. Anesthesiology 89:1218–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee HT, Emala CW, Joo JD, Kim M. 2007. Isoflurane improves survival and protects against renal and hepatic injury in murine septic peritonitis. Shock 27:373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HT, Kim M, Kim M, Kim N, Billings FT, 4th, D'Agati VD, Emala CW., Sr 2007. Isoflurane protects against renal ischemia and reperfusion injury and modulates leukocyte infiltration in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293:F713–F722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Man K, Lo CM, Ng IO, Wong YC, Qin LF, Fan ST, Wong J. 2001. Liver transplantation in rats using small-for-size grafts: a study of hemodynamic and morphological changes. Arch Surg 136:280–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neder Meyer T, Lazaro Da Silva A. 2004. Ketamine reduces mortality of severely burnt rats, when compared to midazolam plus fentanyl. Burns 30:425–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Omura T, Ascher NL, Emond JC. 1996. Fifty-percent partial liver transplantation in the rat. Transplantation 62:292–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng Y, Gong JP, Liu CA, Wang W, Lan YN. 2003. Selection of anesthetic method in setting up the model of orthotopic liver transplantation in rats. Chin J Gen Surg 12:673–676 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rainsford KD. 2007. Antiinflammatory drugs in the 21st century. Subcell Biochem 42:3–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reuben SS, Buvanendran A. 2007. Preventing the development of chronic pain after orthopaedic surgery with preventive multimodal analgesic techniques. J Bone Joint Surg Am 89:1343–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roytblat L, Talmor D, Rachinsky M, Greemberg L, Pekar A, Appelbaum A, Gurman GM, Shapira Y, Duvdenani A. 1998. Ketamine attenuates the interleukin-6 response after cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg 87:266–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakai T, Ichiyama T, Whitten CW, Giesecke AH, Lipton JM. 2000. Ketamine suppresses endotoxin-induced NFκB expression. Can J Anaesth 47:1019–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaked G, Czeiger D, Dukhno O, Levy I, Artru AA, Shapira Y, Douvdevani A. 2004. Ketamine improves survival and suppresses IL6 and TNFα production in a model of Gram-negative bacterial sepsis in rats. Resuscitation 62:237–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strey CW, Markiewski M, Mastellos D, Tudoran R, Spruce LA, Greenbaum LE, Lambris JD. 2003. The proinflammatory mediators C3a and C5a are essential for liver regeneration. J Exp Med 198:913–923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suliburk JW, Helmer KS, Gonzalez EA, Robinson EK, Mercer DW. 2005. Ketamine attenuates liver injury attributed to endotoxemia: role of cyclooxygenase 2. Surgery 138:134–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun J, Wang XD, Liu H, Xu JG. 2004. Ketamine suppresses endotoxin-induced NFκB activation and cytokines production in the intestine. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 48:317–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tian Y, Graf R, Jochum W, Clavien PA. 2003. Arterialized partial orthotopic liver transplantation in the mouse: a new model and evaluation of the critical liver mass. Liver Transpl 9:789–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker JS. 1995. NSAID: an update on their analgesic effects. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 22:855–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welberg LA, Kinkead B, Thrivikraman K, Huerkamp MJ, Nemeroff CB, Plotsky PM. 2006. Ketamine–xylazine–acepromazine anesthesia and postoperative recovery in rats. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 45:13–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaugg M, Lucchinetti E, Spahn DR, Pasch T, Garcia C, Schaub MC. 2002. Differential effects of anesthetics on mitochondrial K(ATP) channel activity and cardiomyocyte protection. Anesthesiology 97:15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]