Abstract

Many inhibitors of the EGFR-RAS-PI3 kinase-AKT signaling pathway are in clinical use or under development for cancer therapy. Here we show that treatment of mice bearing human tumor xenografts with inhibitors that block EGFR, RAS, PI3 kinase or AKT resulted in prolonged and durable enhancement of tumor vascular flow, perfusion and decreased tumor hypoxia. The vessels in the treated tumors had decreased tortuosity and increased internodal length accounting for the functional alterations. Inhibition of tumor growth cannot account for these results as the drugs were given at doses that did not alter tumor growth. The tumor cell itself was an essential target as HT1080 tumors that lack EGFR did not respond to an EGFR inhibitor, but did respond with vascular alterations to RAS or PI3 Kinase inhibition. We extended these observations to spontaneously arising tumors in MMTV-neu mice. These tumors also responded to PI3 kinase inhibition with decreased tumor hypoxia, increased vascular flow and morphological alterations of their vessels including increased vascular maturity and acquisition of pericyte markers. These changes are similar to the vascular normalization that has been described after anti-angiogenic treatment of xenografts. One difficulty in the use of vascular normalization as a therapeutic strategy has been its limited duration. In contrast, blocking tumor cell RAS-PI3K-AKT signaling led to persistent vascular changes that might be incorporated into clinical strategies based on improvement of vascular flow or decreased hypoxia. These results indicate that vascular alterations must be considered as a consequence of signaling inhibition in cancer therapy.

Keywords: Signaling inhibition, tumor vasculature, hypoxia, EGFR, RAS, PI3 Kinase, AKT

Introduction

Tumor growth requires induction of angiogenesis to maintain nutrient and oxygen supplies to rapidly dividing cells. However, tumor vasculature is often disorganized with blood vessels that are aberrant both morphologically and functionally. The vessels are often dilated, irregular in distribution and shape, and have abnormal pericyte and basement membrane coverage (1, 2). As a result, vasculature function is compromised. Perfusion of tumor vessels is variable and subject to interruptions. The vessels are leaky, leading to high tumor interstitial pressure that can disrupt diffusion into the tumor stroma (3). These defects contribute to tumor hypoxia, which is associated with poor prognosis and treatment response.

Clinically, hypoxic tumors are more resistant to radiation therapy in part because radiation requires oxygen for maximal fixation of the radical species that cause DNA damage (4). Hypoxic tumors also resist cytotoxic drug treatment because of poor perfusion and diffusion into hypoxic tumor areas and because hypoxia both impedes the function of some cytoxic drugs and may induce resistance mechanisms (reviewed in (5, 6)).

Treatments that target tumor vasculature ablate vascular flow or reduce tumor angiogenesis, but these approaches are likely to exacerbate hypoxia. Vasculature-targeting drugs such as Combretastatin are toxic to tumor vessels, leading to necrosis in the central areas of tumors and result in diminished perfusion and increased central hypoxia (7). However peripheral vascular supplies and neoangiogenesis can maintain viable tumor cells in the tumor periphery leading to tumor regrowth (8). In addition, the anti-vascular effects of the therapy can decrease subsequent cytotoxic drug delivery and diminish radiation cytotoxicity due to reduced tumor oygenation.

A second approach to modifying vascular function is to block tumor angiogenic signaling. Normal tissue angiogenesis is a well-regulated process that balances pro- and anti-angiogenic signaling, resulting in the formation of ordered, mature vessels with basement membrane support and abundant pericyte coverage. In contrast, tumor angiogenesis is deregulated, with a preponderance of pro-angiogenic signaling, primarily through the overproduction of VEGF. VEGF over-expression is linked to signaling by pathways that are constitutively activated in tumor cells (9). Treatment with antibodies targeting the VEGF receptor results in transient enhancement of vascular function termed “vascular normalization”. The accompanying period of enhanced oxygenation corresponded to a period of enhanced radiosensitivity in treated tumors (10). However, the transient nature of these changes poses problems for clinical application of this approach.

Because tumor angiogenesis is linked to activation of oncogenic signaling pathways, another approach to modulating tumor vasculature is to target these pathways. However the effects of tumor signaling inhibition on tumor vasculature has not been well characterized. Targeting RAS activation with FTIs was shown to increase oxygenation in tumor xenografts (11). Treatment of tumor bearing mice with nelfinavir, a protease inhibitor with pleotropic effects including down-regulation of Akt signaling also led to enhanced tumor oxygenation and correlated with decreased VEGF expression (12). Although both studies showed significant changes in tumor oxygenation, the mechanisms for these changes were not defined. We have now explored the vascular changes that could account for the changes in oxygenation and asked whether inhibition at other points in the RAS signaling pathway would have similar effects.

In this report we show that treatment of mice bearing tumors with agents that disrupt the EGFR-RAS-PI3K-AKT signaling pathway at each of these points results in increased tumor oxygenation. Treatment with each of these inhibitors leads to morphologic changes that promote increased perfusion. Most importantly the approach of targeting tumor signaling yields a sustained effect that may allow prolonged enhancement of drug delivery and improved efficacy of radiation therapy.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

Cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, Utah) at 37°C in water-saturated 5% CO2. The HT1080 cell line expressing pGL-HRE, a luciferase reporter construct driven by three HRE binding sequences for HIF, was kindly provided by Christopher Pugh (Oxford, UK). SQ20B cells were transfected with pGL-HRE and transfectants selected with 2μg/ml Puromycin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). Resistant clones were selected.

Examination of hypoxia response in vitro

To determine the kinetics of luciferase expression under hypoxia and re-oxygenation, cells were seeded in 6 or 96 well plates and cultured in phenol-free L-15 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum under hypoxia (0.1% O2) using the Invivo 400 system (Ruskinn, Bridgend, UK). At 0, 8, 16 or 24h, cells in 96 well plates were lysed and assayed using the Steady-Glo luciferase assay kit (Promega, Fitchburg, WI). Live cell images of luminescence were obtained on the IVIS 200 optical imaging system (Xenogen, Alameda, CA) after addition of luciferin (150mg/mL) to cells in 6 well plates. Both methods gave equivalent results. For reoxygenation studies, 6 well plates seeded with 400,000 cells were maintained under 0.1% hypoxia for 16 hours. Images were acquired on replicate cultures at 15 minute intervals after reoxygenation.

Inhibitor treatment of mice

All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with UK Home Office regulations. Female SCID mice (Charles River) were inoculated with 106 cells on the hind leg subcutaneously. Treatments were initiated when tumors reached 100mm3. In all experiments, animals were treated with carrier (50% DMSO, 50% PBS), L778,123 (40mg/kg), Iressa (50mg/kg), Nelfinavir (20mg/kg) or PI-103 (5mg/kg) by daily i.p. injections. Inhibitors were given daily for up to 2 weeks. Transgenic mice (FVB/N-Tg(MMTVneu)202Mul/J), were treated with either carrier or PI-103 by daily injections for 2 weeks once tumors had reached 150-200mm3.

In vivo imaging

Optical and ultrasound/power Doppler were carried out under anesthesia (2% isofluorane in oxygen). Luciferin (150mg/kg, Xenogen, Alameda, CA) was administered i.p. 5 min before optical imaging on an IVIS 200 system (Xenogen). Ultrasound imaging was done on a Vevo770 (Visualsonics, Toronto, Canada). Doppler image analysis was done with Visualsonics software as described in (13). Ultrasound microbubble contrast imaging was done after bolus iv injection of non-targeting contrast reagent (Visualsonics). Propriety software modules were used for analysis of visual and ultrasound measurements. Microbubble influx was quantified using a Visualsonics software module based on (14).

Confocal/Multiphoton microscopy

At the indicated times, animals were injected with 0.01ml/g body weight of 10mM nitroimmidazole hypoxic cell marker, EF5 dissolved in glucose/normal saline and administered 3 hours (i.v.) and 2.5 hours (i.p.) before sacrifice (Complete protocols for the use of EF5 are available on: http//www.hypoxia-imaging.org). Vascular perfusion was visualized with anti-CD31-RPE conjugated antibody (20ug, 102408, Biolegand, San Diego, CA) and extravascular diffusion with either Hoechst dye (0.4mg, Sigma, Dorset, UK) or 10 kMW Dextran-Alexa-647 (0.4mg, D22914, Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) injected 10 min and 1 min before sacrifice respectively. Tumors were immediately excised and sectioned into three parts. A central 1mm thick section was immediately imaged using Confocal/Multiphoton microscropy (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Adjacent sections were snap frozen or preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde. Confocal/Multiphoton stacks of 100 microns were taken at 0.5 micron intervals, using a 20× lens, on multiple fields using the 488 laser to excite GFP, 543nm laser to excite anti-CD31-RPE and 740nm Mai-Tai femtosecond pulsing laser (Spectra Physics, Mountain View, CA) to excite Hoechst or 633 laser to excite Dextran-Alexa-647. Mean pixel number for CD31-RPE and Hoechst staining for each100 micron stack was calculated using proprietary software (Leica). 3D vascular reconstructions were compiled using Amira 3D software (Visage Imaging, Carlsbad, CA). Calculation of vessel geometry and statistics was performed using Trace 3D software (15). Determinations of tortuosity and vessel length was as described by Norrby (16).

Immunofluorescence, Immunohistochemistry and ELISA studies

EF5 binding was detected with ELK3-51 monoclonal antibody as previously described (11). Immunofluorescence staining for PDGF-β (1:100, ab32570, Abcam, Cambridge UK), SMA (1:300, ab5694, Abcam) and CD31 (1:50, 09151A, BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) was performed using the TSA biotin system (Pelkin-Elmer,Waltham, MA) and streptavidin conjugated fluorophores Alexa fluor 488 and 546 (Invitrogen). Images were acquired using a Leica DM IRBE microscope with a Hamamatsu C4742-95 camera. Image analysis was done using ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij). Staining for Carbonic Anhydrase IX (1:1000, ab15086, Abcam) and EGFR (1:100, ab2430, Abcam) was detected using the ImmPress Anti-Rabbit IgG (peroxidase) kit (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) and visualised using an Axioskop 2 microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). VEGF levels were determined using the Quantikine VEGF ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK).

Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise stated, error bars indicate S.E.M., and p values <0.05 after a two-tailed t -test are denoted by an asterisk in the figures.

Results

Reporters for in vivo detection of tumor hypoxia

Tumor cells expressing luciferase under control of three HIF hypoxia responsive elements (HRE-luc) were generated from SQ20B laryngeal carcinoma cells and from HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells. In tissue culture, exposure of the cells to hypoxia (0.1% O2) resulted in induction of luciferase within 8h reaching a maximum by 16h in both lines. Re-oxygenation of cultures reduced luciferase to basal levels after 2h (Supplemental Figure 1). Both models thus are useful reporters for oxygenation.

Effects of signaling inhibition on tumor hypoxia

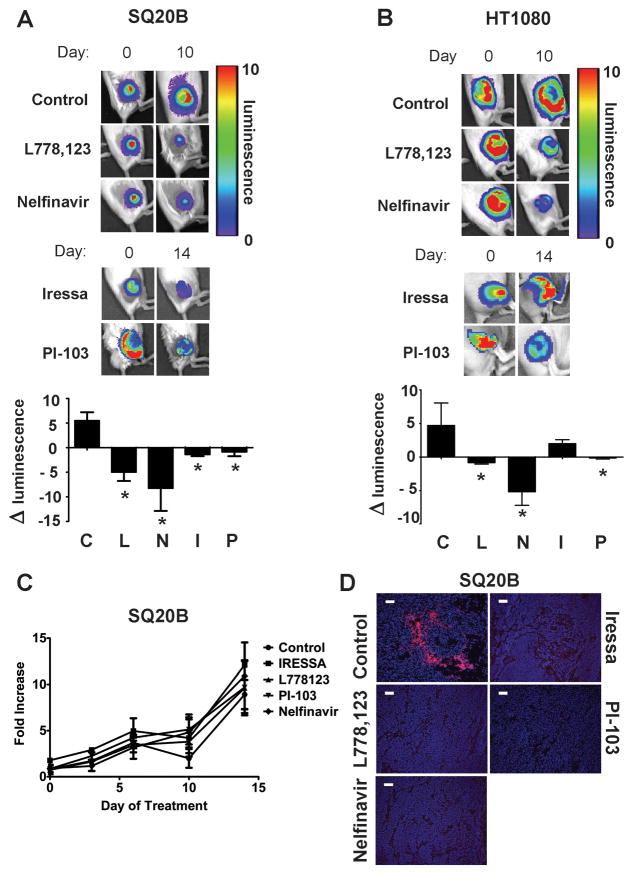

The two cell lines have active RAS-PI3K-AKT signaling. SQ20B over-expresses EGFR, which causes constitutive activation of RAS and activation of PI3K and AKT. HT1080 has an oncogenic mutation in N-ras that results in constitutively active PI3K and AKT. Inhibitors that block the EGFR-RAS-PI3K-AKT pathway at different points were utilized to block signaling. Iressa blocks EGFR tyrosine kinase signaling. The farnesyltransferase inhibitor, L-778,123 inhibits both wild type H-RAS and the mutated N-RAS by blocking their prenylation. The class I PI3K inhibitor, PI-103 blocks class I PI3K signaling. Nelfinavir (Viracept) is a protease inhibitor that indirectly down-regulates AKT activity (17). Treatment of mice bearing size-matched SQ20B-luc tumors was initiated after a preliminary scan for luciferase expression. Ten days later, the control tumors had increased luciferase expression consistent with increased hypoxia (Figure 1A). In contrast, tumors in mice treated with Iressa, L-778,123, PI-103 or Nelfinavir showed decreased luciferase expression consistent with decreased hypoxia. This was confirmed by decreased binding of the nitroimidazole hypoxia marker EF5 (Figure 1D). Decreased expression of the hypoxia responsive genes CA-IX and VEGF was also observed (Supplementary Figure 2). Altered tumor growth did not account for the changes in tumor oxygenation since the growth of the treated tumors was not different from controls (Figure 1C). Thus inhibition of tumor signaling through EGFR-RAS-PI3K-AKT resulted in significant reduction in tumor hypoxia.

Figure 1. Tumor hypoxia is reduced after signaling inhibition.

Tumors in SCID mice were generated from the HRE-luc SQ20B and the HRE-luc HT1080 cells. When the tumors reached at least 100mm3 in volume, bioluminescent imaging was performed. At the indicated time of treatment with the indicated drugs, bioluminescent imaging was again performed. * indicates p<0.05 by two tailed t-tests compared to controls.

a. Representative images from bioluminescent imaging at 10d (L-778,123 (40mg/kg) and Nelfinavir (20mg/kg)) and 14d (Iressa (50mg/kg) and PI-103 (5mg/kg)) to detect luciferase expression in animals bearing SQ20B-luc xenografts.

b. Representative images from bioluminescent imaging at 10d treatment as in (a) to detect luciferase expression in animals bearing HT1080-luc xenografts.

c. SQ20B xenograft tumor growth measured throughout the time of inhibitor treatment is unaffected by signaling inhibition (p=0.966, ANOVA).

d. Immunohistochemistry confirms a reduction in EF5 binding in treated SQ20B tumors from (a).

Inhibition of RAS, PI3K or AKT in HT1080 reduced hypoxia without reducing tumor growth similar to the results obtained in SQ20B (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 3). Although one group (18) has reported EGFR expression in their HT1080 tumors, we did not detect human EGFR staining in HT1080 tumors (Supplementary Figure 4). Thus HT1080 oncogenic signaling through RAS-PI3K-AKT should be independent of EGFR. Consistent with this, treatment of HT1080 tumor-bearing mice with the same dose of Iressa used on SQ20B tumor-bearing mice did not alter tumor hypoxia (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 3). These data are consistent with tumor EGFR as the target for Iressa that leads to reduction in tumor hypoxia.

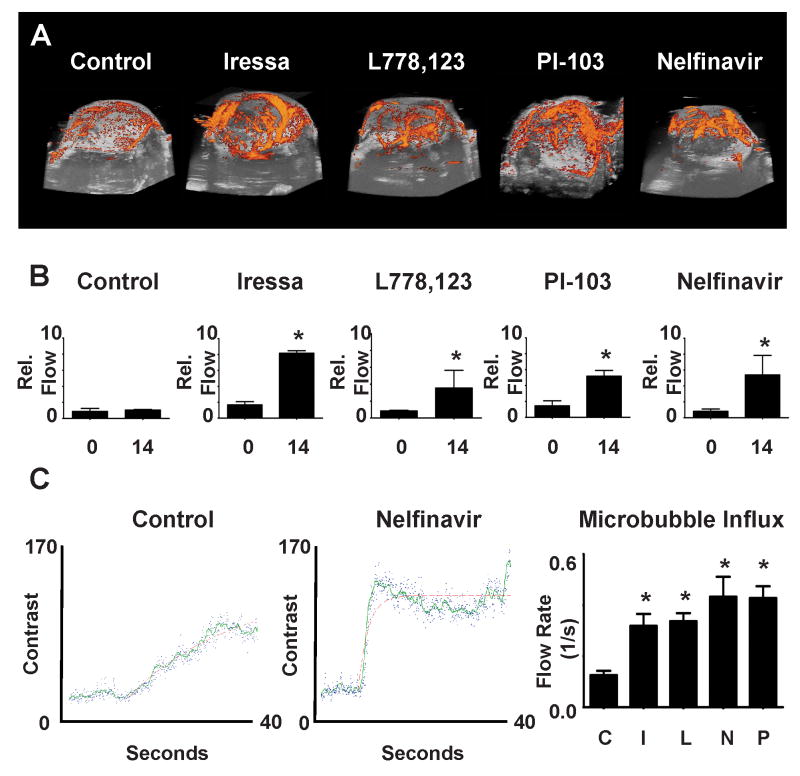

Effects of signaling inhibition on tumor blood flow

To define the mechanisms for reduction of hypoxia after signaling inhibition, we examined the functional status of tumor vasculature. 3D ultrasound power Doppler was used to measure and provide a 3D-visual representation of SQ20B tumor vascular function. 3D reconstructions of serial Doppler scans through individual tumors show that vascular flow in treated tumors is significantly greater than in control tumors (Figure 2A, 2B). Similar results were seen in HT1080 tumors treated with either PI-103 or Nelfinavir, while Iressa treatment showed no effect (Supplementary Figure 5). To quantitate the rate of vascular flow in SQ20B tumors, micro-bubble contrast reagent influx was measured (Figure 2C). The slope and magnitude of micro-bubble influx permits quantitation of tumor vascular flow. The rate of flow in HRE-luc SQ20B tumors after treatment of the mice with either Iressa, L-778,123 or nelfinavir increased at least two-fold (Figure 2C). Thus increased oxygenation after signaling inhibition was associated with an increase in tumor perfusion.

Figure 2. Signaling inhibition increases tumor blood flow.

Tumor blood flow determinations using Doppler ultrasound on xenograft tumors in SCID mice generated from the HRE-luc SQ20B and the HRE-luc HT1080 cells.

a. Representative images from 3D power Doppler reconstruction of tumor vascular flow after 14 days treatment with Iressa, L-778,123, PI-103 or Nelfinavir treated as in Figure 1.

b. Quantification of Doppler signal:volume ratio shows increases after signaling inhibition in longitudinal studies in tumors after 14 days (Control: p=0.684; Iressa: p=0.006; L778,123: p=0.050; PI-103: p=0.018; Nelfinavir: 0.046. P-values from two tailed t-tests compared to controls)

c. Examples of raw contrast kinetics acquired in control (left) and treated (middle, nelfinavir) after bolus i.v. injection of microbubble contrast reagent. Quantification of microbubble velocity in multiple areas within SQ20B tumors (right) in multiple animals demonstrate a significant increase in influx within the tumor parenchyma, (all starred p values <0.001, ANOVA = 0.0002)

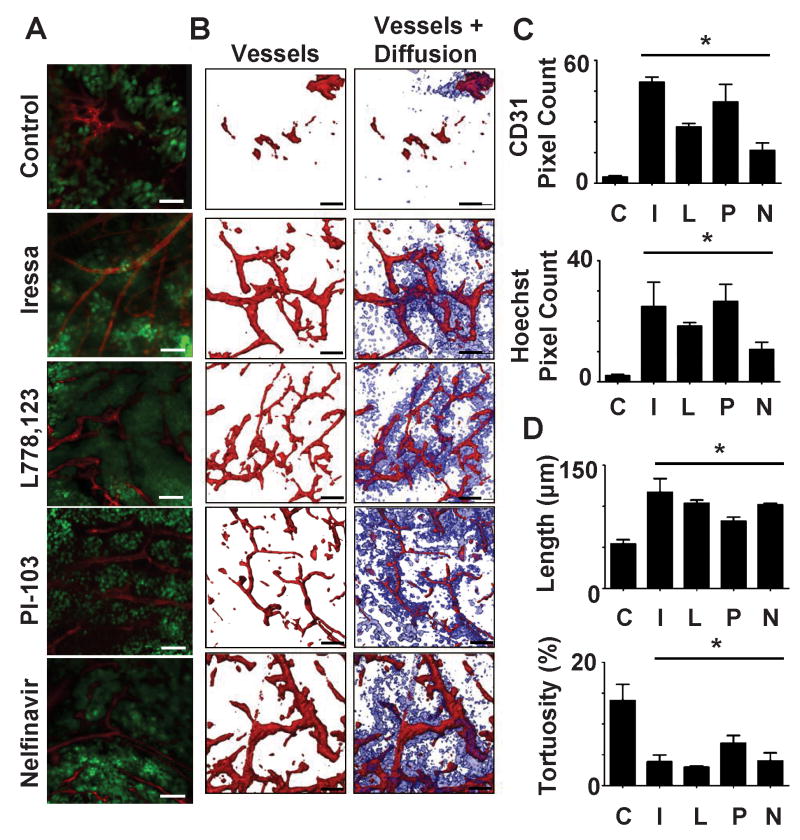

Treated tumors demonstrate increased vascularity and extravascular diffusion of small molecules

We utilized ex-vivo microscopy to visualize the morphology of the tumor vasculature. Mice were injected iv with a fluorescently tagged anti-endothelial cell antibody (CD31-RPE), then with Hoechst dye. Anti-CD31 binds to vessel walls in perfused vessels thus indicating the extent of vascular perfusion during the 10 min. interval between injection of this antibody and sacrifice of the mouse. Hoeschst dye is highly diffusible outside of vessels. The extent of Hoeschst dye staining reflects both the extent of effective perfusion and the extent of diffusion of small molecules from the vasculature. Fresh tumor sections were imaged by confocal/multi-photon microscopy over a depth of 100μ at 0.5μ intervals (Figure 3A). A comparison of 3D reconstructions of SQ20B tumors from control mice or mice treated with either Iressa, L-778,123 or Nelfinavir revealed that treated tumors had increased perfused vascular density (Figure 3B,C). A quantitative examination of the morphology of the vessels showed that the vessels in tumors from mice treated with any of the inhibitors were more regular with increased inter-branched length and reduced tortuosity (Figure 3D, Supplementary Figure 6). Similar results were obtained in HT1080 tumors treated with Nelfinavir or PI-103, while Iressa treatment had no significant effects, consistent with the lack of EGFR expression (Supplementary Figure 7). The vessels in treated SQ20B and HT1080 tumors also showed enhanced staining with PDGFβ, a marker of vascular maturity (Supplementary Figure 8). These patterns are consistent with enhanced flow.

Figure 3. Treated tumors demonstrate normalized vascular morphology.

SCID mice with SQ20B-GFP tumors were treated with either carrier (50% DMSO, 50% PBS), L778,123 (L, 40mg/kg), Iressa (I, 50mg/kg), Nelfinavir (N) (20mg/kg) or PI-103 (P, 5mg/kg) by daily i.p. injections. CD31-PE and Hoescht were injected iv at 10 min. and 1min. respectively prior to sacrifice. * indicates p<0.05 using two tailed t-tests compared to controls.

a. Representative images from a single 0.5μm optical section of tumors showing tumor (green), vascular morphology (red) after indicated treatments.

b. 100μm 3D reconstructions of vascular morphology (red) and extra-vascular diffusion (blue).

c. Quantitation of perfused vessel density (CD31 staining) and extravascular diffusion (Hoechst staining).

d. Calculation of uninterrupted vessel length and tortuosity from the computer generated tracings of vasculature based upon the 3D reconstructions of tumors (for examples see Supplementary Figure 5).

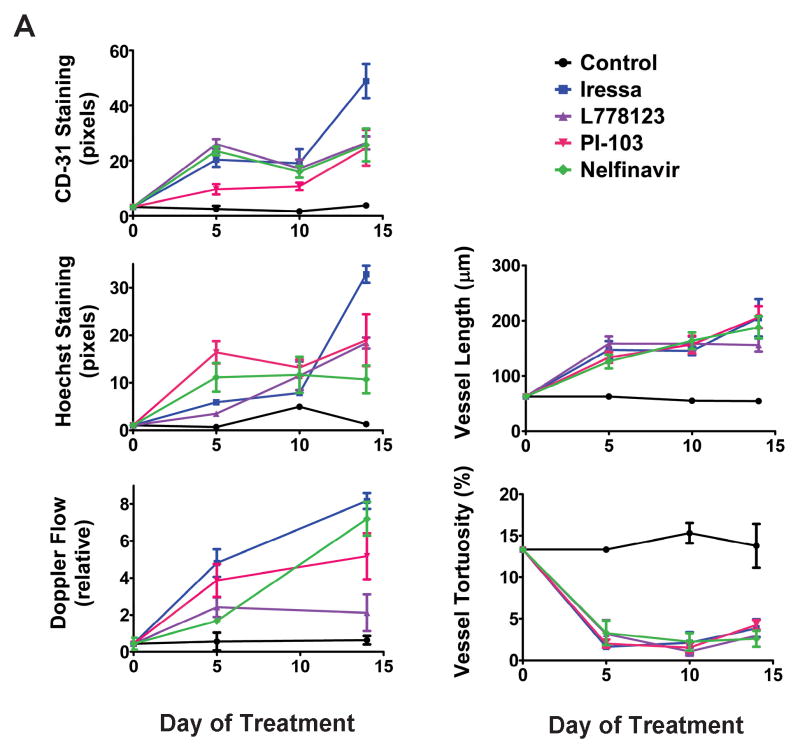

The changes seen in SQ20B tumor vasculature after treatment with signaling inhibition persisted throughout the time course of these experiments (Figure 4). Changes were evident 5 days after initiation of treatment and persisted until 14 days after treatment began (at which time experiments were terminated to prevent exceeding tumor size limitations). Thus the enhanced vascular function and morphological changes induced by signaling inhibition is more durable than that reported in response to anti-angiogenic agents.

Figure 4. Vascular normalization persists during a 5-14 day timecourse.

Xenograft tumors in SCID mice were generated from the SQ20B-GFP and treated with the indicated inhibitors as in Figure1. Each time-point represents a different cohort of mice.

a. Top, left: Quantitation of CD31 vascular staining as assessed by confocal microscopy. Middle, left: Quantitation of Hoechst staining as assessed by multiphoton microscopy.

Middle, right: Vascular flow determinations based on Doppler ultrasound imaging prior to sacrifice for confocal/multiphoton imaging.

Bottom, Left: Uninterrupted tumor vessel length calculated as in Fig 3d for each treatment group at each of three timepoints.

Bottom, Right: Tumor vessel tortuosity calculated as in Fig 3d at three timepoints during treatment.

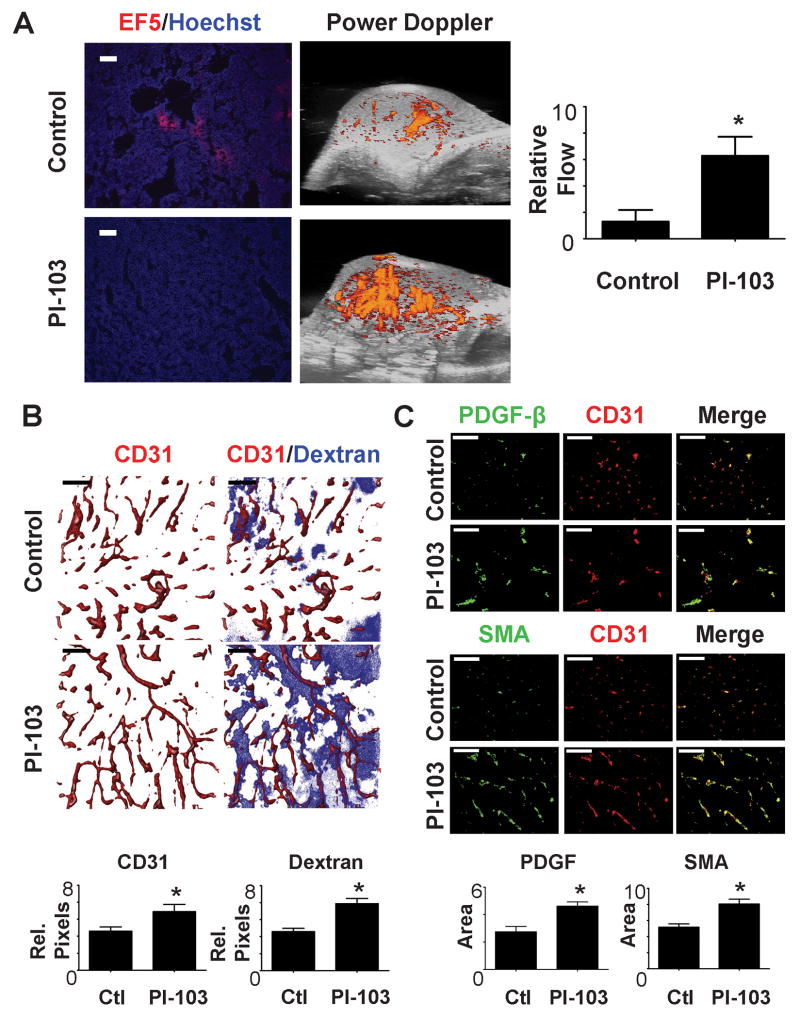

Inhibition of signaling causes vascular normalization in transgenic tumor model

Studies of angiogenic changes in xenograft models are instructive, but the tumor vasculature in xenografts probably develops in a very different way than the vasculature in spontaneous tumors. Furthermore, growth of human tumor xenografts requires immunosuppressed mice. We therefore examined changes resulting from signaling inhibition in a spontaneous mouse mammary tumor model. FVB-MMTV-Neu mice were monitored until tumors arose, and then enrolled into control or PI-103 treatment groups. These tumors have enhanced signaling through PI3K (19, 20). Ten days of treatment with PI-103 resulted in increased vascular flow and enhanced tumor oxygenation relative to control tumors (Figure 5A). In comparison with the xenograft model, untreated tumors had a greater vascular density than xenograft tumors. Nonetheless, vascular density and diffusion from this vasculature were enhanced by PI-103 treatment (Figure 5B). The tumor vessels in the treated mice also showed increased expression of SMA and PDGFβ (Figure 5C) consistent with a mature morphology. Analysis of the vascular morphology indicated that vessels in the treated tumors had increased length and decreased toutuosity (Supplemental Figure 9). Thus in these spontaneous tumors, inhibition of PI3K resulted in prolonged changes in vascular morphology resulting in enhanced function and decreased hypoxia.

Figure 5. Specific inhibition of PI-3K in a transgenic MMTV Neu model results in vascular normalization.

Female mice bearing the MMTV-neu transgene were entered into the experiment when they had developed tumors of 150-200 mm3 in volume. After initial examination, the mice were treated with P-103 (5mg/kg) for 10 days. All p values are from two tailed t-tests compared to controls. * indicates p<0.05.

a. Representative images of hypoxia (EF5) staining and 3D reconstruction of Doppler evaluation of breast carcinoma perfusion. Vascular perfusion is increased while hypoxia is reduced. Quantitation of power Doppler signal from images shows significant increase in vascular perfusion after PI-103 treatment.

b. At timed intervals prior to sacrifice CD31-PE (10 min.) and dextran (1min.) were injected iv. Tumor vessel morphology was examined as in Figure 3. Quantitation shows an increased in perfused vessel density and an increase in dextran due to extravascular diffusion. Computer generated vascular tracings and further quantitation are shown in Supplemental Figure 6.

c. Evaluation and quantitation of vascular maturity by immunohistochemical staining for smooth muscle actin (SMA) and PDGF-β.

Discussion

Enhanced tumor oxygenation has long been sought as a means to improve the efficacy of radiation therapy. Transiently increased oxygenation of tumors has been described in response to anti-angiogenic agents directed at the tumor vasculature (reviewed in (21)). The current report demonstrates an alternate approach. We show that targeting tumor signaling in the RAS-PI3K-AKT pathway leads to a sustained vascular response and increased oxygenation suggesting that this strategy might readily translate into clinical use.

Previous studies documenting vascular normalization used xenografts models. Because the process of vascularization of a xenografted tumor differs markedly from vascularization of spontaneously arising tumors, it was conceivable that xenografts and spontaneous tumors would differ in their vascular responses. However, we found that PI3K inhibition reduced hypoxia and normalized vasculture in a transgene-induced breast cancer model. The MMTV-Neu model that we used is known to ultilize signaling through this pathway (19, 20). Although the vasculature in the transgene-induced tumors was more regular and denser than that of xenografts, treatment with PI-103 still led to increased vascular density, longer vessels, increased vascular flow and decreased hypoxia and morphological changes consistent with vascular normalization over the two-week experimental timecourse. Thus vascular normalization can be demonstrated in transgenic tumor models as well as xenografts.

The RAS-PI3K-AKT pathway is activated in many human cancers. Each component of this signaling pathway is activated in the SQ20B and HT1080 cell lines and in the spontaneous MMTV-Neu induced tumors. Each of the drugs tested inhibits at a different point in the RAS to AKT pathway. In our studies, Iressa, L-778,123, PI-103 and nelfinavir did not alter tumor growth. In general, the effects of these drugs on tumor growth are variable with some instances of tumor growth inhibition, but also reports in which growth was not affected. For example, PI-103 inhibited the growth of a Kaposi sarcoma as a xenograft although the dose was higher than that used here (22). In contrast, PI-103 did not inhibit the growth of glioblastoma cell line U251 grown as a xenograft (23). The glioblastoma cell line U87 was inhibited but not before 17 days of treatment (24).

Each of these inhibitors has a different mode of action and different known off-target effects. L-778,123 inhibits farnesyl- and geranylgeranyl-transferases, resulting in RAS inhibition while also affecting other prenylated proteins (25). FTI treatment results in radiosensitization and reduced tumor hypoxia, but the mechanisms for these effects have not been defined previously (11, 26). PI-103 is one of the most specific class I PI3 Kinase inhibitors available, though it also blocks mTOR and DNA-PK (24, 27). In a report by Chen et al. 10mg/kg/d PI-103 showed no effect on U251 glioblastoma growth while combining PI-103 treatment with radiation, sensitized these tumors. Nelfinavir, although designed to be an HIV protease inhibitor, also blocks the chymotrypsin-like proteasome subunit (28, 29). Nelfinavir inhibition of AKT is indirect and may involve the unfolded protein response thus affecting other signaling pathways (17, 30). Nelfinavir treatment has been shown to result in reduced tumor hypoxia, decreased levels of VEGF and in radiosensitization of xenografts (12, 17). Pore et al. noted anti-angiogenic effects from nelfinavir in matrigel plug angiogenesis assays admixed with tumor cells (31). The effects on tumor vasculature were not defined in these studies. Although each of these compounds has off-target effects, they all act on different points in EGFR to AKT signaling and there is no obvious confounding off-target effect that would be common to these different agents and could explain the shared effect on tumor vasculature.

Activation of the RAS-AKT pathway in SQ20B is due to EGFR over-expression, which is common in many head and neck squamous cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas (32, 33). Treatment with Iressa, a specific EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, caused enhanced tumor blood flow, increased vascularity and maturation, and increased oxygenation in SQ20B tumors. In contrast, Iressa treatment of mice bearing HT1080 xenografts had little effect on tumor vasculature or hypoxia. In our studies, HT1080 did not express EGFR either in tissue culture or as a tumor. These data suggest that the tumor cells, rather than the host vascular endothelial cells, are the primary targets for initiation of vascular normalization. If vascular endothelium was the direct target of inhibition, then Iressa treatment should have resulted in similar effects in HT1080 tumors to those seen in Iressa-treated SQ20B tumors. Tumor vasculature expresses EGFR and EGFR inhibitors can lead to anti-angiogenic effects (34). However the dose of EGFR inhibitors that leads to such vascular effects is greater than the dose used here. Consistent with these published studies, we have seen anti-angiogenic effects rather than vascular normalization in SQ20B tumors at higher doses of Iressa (data not shown).

We did not detect any alterations in tumor growth or decreased tumor cellularity after inhibitor treatment. Thus reduced tumor growth rates do not account for the enhanced vasculature and oxygenation. It is perhaps surprising that the tumor growth rates were not higher in treated tumors due to increased tumor vasculature and oxygenation. It is possible that the potential for increased tumor growth due to increased blood supply was countered by the anti-proliferative effects of the signaling inhibitors. However, these data raise the question of whether treatment of tumors with low doses of signaling inhibitors as single agents might, by increasing the effectiveness of the vasculature, lead to enhanced tumor growth in the long term. Our results could indicate that these agents need to be used in conjunction with cytotoxic agents or risk enhancing the functionality of tumor vasculature.

These inhibitors can also alter tumor metabolism and potentially affect tumor oxygen levels through this route. Tumor vascular alterations might also result from alterations in oxygen levels. Recently, Mazzone et al showed evidence of vascular normalization with increased tumor oxygenation, increased vascular flow and increased pericyte coverage in tumors grown in PHD2 +/- mice (35). The decreased levels of endothelial PDH2 in these mice was shown to increase HIF, resulting in upregulation of soluble VEGFR-1 and VE-cadherin. This perturbation of the normal oxygen sensing mechanisms thereby resulted in increased oxygenation in tumor grafts. If the signaling inhibitors used in this study alter oxygen consumption, they might also trigger a feedback loop leading to increased oxygen levels and vascular normalization. The concept these authors propose, that breaking the cycle of hypoxia-induced angiogenic signaling can result in vascular normalization may be analogous to the mechanism we see, apart from the target for inhibition. However, it is hard to see how selective inhibition of PHD2 in the endothelium will be achieved clinically. The selective inhibition of tumor signaling as demonstrated here with currently available drugs is a more clinically applicable approach.

FTI and the proteosome inhibitor nelfinavir have been shown to radiosensitize tumor xenografts with synergy (26, 36). In addition EGFR inhibition has been shown to radiosensitize (37) as has inhibition of PI3K using PI-103 (23). Each of these inhibitors can radiosensitize cells in tissue culture, but the effects in vivo have often been of greater magnitude than the sensitization of tumor cells in culture might predict. Here we have begun to explore mechanisms that could explain the effect that these drugs have on the response of tumors to radiation.

A strategy combining radiation with these signaling inhibitors benefits not only from the decreased hypoxia but also from the demonstrated ability of these antitumor signaling agents to sensitize tumor cells to DNA damage (36, 38-40). Similarly, signaling inhibition might be successfully combined with chemotherapeutic interventions as both perfusion and the diffusion of small molecules was markedly enhanced in treated tumors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sally Hill and Ms. Karla Watson for exceptional help with animal care and Home Office compliance monitoring.

The study was supported by an MRC - Cancer Research UK grant-in-aid, The OCIC supported by CRUK/EPSRC, by NIH RO1 CA73820 (EJB), NIH PO1 CA75138 (GMCK and EJB) and a BCCOE grant from the US Dept. of Defense (RJM). NQ was supported by a Cancer Research UK studentship.

Inhibitors L-778,123 (Merck & Co Inc.) and PI-103 (Genentech) were under material transfer agreements for use in these studies. Professor Christopher Pugh (Wellcome Trust Centre for Molecular Physiology, Oxford) provided the pGL-HRE luciferase reporter construct and HT1080 cells expressing this construct.

References

- 1.Baluk P, Morikawa S, Haskell A, Mancuso M, McDonald DM. Abnormalities of basement membrane on blood vessels and endothelial sprouts in tumors. American Journal of Pathology. 2003;163(5):1801–15. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63540-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morikawa S, Baluk P, Kaidoh T, Haskell A, Jain RK, McDonald DM. Abnormalities in pericytes on blood vessels and endothelial sprouts in tumors. American Journal of Pathology. 2002;160(3):985–1000. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64920-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucher Y, Baxter LT, Jain RK. Interstitial pressure gradients in tissue-isolated and subcutaneous tumors: implications for therapy. Cancer Research. 1990;50(15):4478–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaupel P. Tumor microenvironmental physiology and its implications for radiation oncology. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2004;14(3):198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cosse JP, Michiels C. Tumour hypoxia affects the responsiveness of cancer cells to chemotherapy and promotes cancer progression. Current Medicinal Chemistry - Anti-Cancer Agents. 2008;8(7):790–7. doi: 10.2174/187152008785914798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teicher BA. Hypoxia and drug resistance. Cancer & Metastasis Reviews. 1994;13(2):139–68. doi: 10.1007/BF00689633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horsman MR, Ehrnrooth E, Ladekarl M, Overgaard J. The effect of combretastatin A-4 disodium phosphate in a C3H mouse mammary carcinoma and a variety of murine spontaneous tumors. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 1998;42(4):895–8. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaplin DJ, Hill SA. The development of combretastatin A4 phosphate as a vascular targeting agent. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 2002;54(5):1491–6. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)03924-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rak J, Filmus J, Finkenzeller G, Grugel S, Marme D, Kerbel RS. Oncogenes as inducers of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer & Metastasis Reviews. 1995;14(4):263–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00690598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain RK. Normalizing tumor vasculature with anti-angiogenic therapy: a new paradigm for combination therapy. Nature Medicine. 2001;7(9):987–9. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-987. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen-Jonathan E, Evans SM, Koch CJ, et al. The farnesyltransferase inhibitor L744,832 reduces hypoxia in tumors expressing activated H-ras. Cancer Res. 2001;61(5):2289–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pore N, Gupta AK, Cerniglia GJ, et al. Nelfinavir down-regulates hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha and VEGF expression and increases tumor oxygenation: implications for radiotherapy. Cancer Research. 2006;66(18):9252–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jugold M, Palmowski M, Huppert J, et al. Volumetric high-frequency Doppler ultrasound enables the assessment of early antiangiogenic therapy effects on tumor xenografts in nude mice. European Radiology. 2008;18(4):753–8. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei K, Jayaweera AR, Firoozan S, Linka A, Skyba DM, Kaul S. Quantification of myocardial blood flow with ultrasound-induced destruction of microbubbles administered as a constant venous infusion. Circulation. 1998;97(5):473–83. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.5.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barber PR, Vojnovic B, Ameer-Beg SM, Hodgkiss RJ, Tozer GM, Wilson J. Semi-automated software for the three-dimensional delineation of complex vascular networks. Journal of Microscopy. 2003;211(Pt 1):54–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2003.01205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norrby K. Microvascular density in terms of number and length of microvessel segments per unit tissue volume in mammalian angiogenesis. Microvascular Research. 1998;55(1):43–53. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1997.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta AK, Li B, Cerniglia GJ, Ahmed MS, Hahn SM, Maity A. The HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir downregulates Akt phosphorylation by inhibiting proteasomal activity and inducing the unfolded protein response. Neoplasia (New York) 2007;9(4):271–8. doi: 10.1593/neo.07124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ren W, Korchin B, Zhu QS, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor blockade in combination with conventional chemotherapy inhibits soft tissue sarcoma cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14(9):2785–95. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janes PW, Daly RJ, deFazio A, Sutherland RL. Activation of the Ras signalling pathway in human breast cancer cells overexpressing erbB-2. Oncogene. 1994;9(12):3601–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrechek ER, Muller WJ. Tyrosine kinase signalling in breast cancer: tyrosine kinase-mediated signal transduction in transgenic mouse models of human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2(3):211–6. doi: 10.1186/bcr56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain RK. Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005;307(5706):58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaisuparat R, Hu J, Jham BC, Knight ZA, Shokat KM, Montaner S. Dual inhibition of PI3Kalpha and mTOR as an alternative treatment for Kaposi's sarcoma. Cancer Research. 2008;68(20):8361–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen JS, Zhou LJ, Entin-Meer M, et al. Characterization of structurally distinct, isoform-selective phosphoinositide 3′-kinase inhibitors in combination with radiation in the treatment of glioblastoma. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2008;7(4):841–50. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan QW, Knight ZA, Goldenberg DD, et al. A dual PI3 kinase/mTOR inhibitor reveals emergent efficacy in glioma. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(5):341–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lobell RB, Liu D, Buser CA, et al. Preclinical and clinical pharmacodynamic assessment of L-778,123, a dual inhibitor of farnesyl:protein transferase and geranylgeranyl:protein transferase type-I. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2002;1(9):747–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen-Jonathan E, Muschel RJ, Gillies McKenna W, et al. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors potentiate the antitumor effect of radiation on a human tumor xenograft expressing activated HRAS. Radiat Res. 2000;154(2):125–32. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2000)154[0125:fiptae]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raynaud FI, Eccles S, Clarke PA, et al. Pharmacologic characterization of a potent inhibitor of class I phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases. Cancer Res. 2007;67(12):5840–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamel FG, Fawcett J, Tsui BT, Bennett RG, Duckworth WC. Effect of nelfinavir on insulin metabolism, proteasome activity and protein degradation in HepG2 cells. Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism. 2006;8(6):661–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2005.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piccinini M, Rinaudo MT, Anselmino A, et al. The HIV protease inhibitors nelfinavir and saquinavir, but not a variety of HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors, adversely affect human proteasome function. Antiviral Therapy. 2005;10(2):215–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gills JJ, Lopiccolo J, Tsurutani J, et al. Nelfinavir, A lead HIV protease inhibitor, is a broad-spectrum, anticancer agent that induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, and apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13(17):5183–94. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pore N, Gupta AK, Cerniglia GJ, Maity A. HIV protease inhibitors decrease VEGF/HIF-1alpha expression and angiogenesis in glioblastoma cells. Neoplasia (New York) 2006;8(11):889–95. doi: 10.1593/neo.06535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA, Jr, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small-cell lung carcinomas: correlation between gene copy number and protein expression and impact on prognosis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(20):3798–807. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.069. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalyankrishna S, Grandis JR. Epidermal growth factor receptor biology in head and neck cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(17):2666–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirata A, Ogawa S, Kometani T, et al. ZD1839 (Iressa) induces antiangiogenic effects through inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase. Cancer Research. 2002;62(9):2554–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazzone M, Dettori D, Leite de Oliveira R, et al. Heterozygous deficiency of PHD2 restores tumor oxygenation and inhibits metastasis via endothelial normalization. Cell. 2009;136(5):839–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta AK, Cerniglia GJ, Mick R, McKenna WG, Muschel RJ. HIV protease inhibitors block Akt signaling and radiosensitize tumor cells both in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2005;65(18):8256–65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milas L, Mason K, Hunter N, et al. In vivo enhancement of tumor radioresponse by C225 antiepidermal growth factor receptor antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(2):701–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brunner TB, Cengel KA, Hahn SM, et al. Pancreatic cancer cell radiation survival and prenyltransferase inhibition: the role of K-Ras. Cancer Research. 2005;65(18):8433–41. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cengel KA, Voong KR, Chandrasekaran S, et al. Oncogenic K-Ras signals through epidermal growth factor receptor and wild-type H-Ras to promote radiation survival in pancreatic and colorectal carcinoma cells. Neoplasia (New York) 2007;9(4):341–8. doi: 10.1593/neo.06823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prevo R, Deutsch E, Sampson O, et al. Class I PI3 kinase inhibition by the pyridinylfuranopyrimidine inhibitor PI-103 enhances tumor radiosensitivity. Cancer Research. 2008;68(14):5915–23. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.