Abstract

Introduction:

Smokers tend to smoke when experiencing craving, but even within smoking occasions, craving may vary. We examine variations in craving when people were smoking in various real-world situations.

Methods:

Using Ecological Momentary Assessment, 394 smokers recorded smoking, craving, and smoking context in real time on electronic diaries over 2 weeks of ad libitum smoking. Assessments occurred immediately prior to smoking. Mixed modeling was used to analyze associations between craving and situational variables.

Results:

Craving varied across smoking situations, but the differences were small (<1 on a 0–10 scale). Specifically, craving was higher in smoking situations where smoking was restricted, likely because high craving leads smokers to violate restrictions. Controlling for restrictions, craving was higher when cigarettes were smoked while eating or drinking, were with other people (vs. alone), were in a group of people (vs. other people simply in view), during work (vs. leisure), and during activity (vs. inactivity). In addition, craving was higher for cigarettes smoked early in the day. No differences in craving were observed in relation to drinking alcohol or caffeine (vs. doing anything else), being at work (vs. home), being at a bar or restaurant (vs. all other locations), interacting with others (vs. not interacting), or other people smoking (vs. no others smoking).

Discussion:

Even though most craving reports prior to smoking were high, and situations were thus expected to have little influence on craving, results suggest that some cigarettes are craved more than others across different smoking situations, but differences are small.

Introduction

Smoking may be triggered by a variety of stimuli: interoceptive cues such as decreases in nicotine blood levels (Jarvik et al., 2000), as well as external cues such as breaks in activity, eating, drinking, and the presence of other smokers, have been associated with increased likelihood of smoking (Shiffman et al., 2002). Craving is thought to be an important signal for smoking, and the probability of smoking increases as craving levels rise (Shiffman et al, 2002). However, not all cigarettes are smoked at times of high craving: Smoking can occur at low levels of craving or even in the absence of craving (Shiffman et al., 2002; Tiffany, 1990). As demonstrated by cue reactivity studies, craving, like smoking, varies in response to various stimuli (see Carter & Tiffany, 1999), including different environmental contexts (Conklin, 2006). However, most work in this area has assessed craving in the laboratory and when individuals are not smoking. This paper addresses variations in craving during smoking episodes in real-world settings.

Quantifying the covariation of craving with real-world smoking situations may provide a clearer picture of the situational factors that motivate smokers to smoke. In cessation attempts, smokers cite craving as one of the most salient and difficult obstacles to successful quitting (Shiffman & Jarvik, 1976; West, Hajek, & Belcher, 1989). Situations in which people typically smoke or experience craving are considered “high-risk situations” for relapse (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). Consequently, exploring variation in craving across smoking situations may highlight contextual features of potential relapse situations; smoking situations in which cigarettes are craved the most may be the ones that later provoke relapse. To date, potential variation of craving across different cigarettes and smoking situations has not been examined explicitly.

In order to test whether craving varies across different smoking occasions and whether or not such variability can be attributed to contextual variables, we focused our analyses on variables that have previously shown associations with ad libitum smoking, including location (particularly home and work, which account for 73% of all cigarettes), activity, and consumption of food and drink, particularly alcohol (Shiffman & Paty, 2006; Shiffman et al., 2002). We also examined variables that have been shown to provoke craving in laboratory studies. The sight of other people smoking reliably elicits increases in craving (see Carter & Tiffany, 1999), and others smoking in a person’s environment can function as a cue to smoke (Conklin, 2006). Furthermore, cigarettes smoked early in the day are thought to be associated with a particular motivation to smoke, given overnight clearance of nicotine (e.g., Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerstrom, 1991), and recent work has demonstrated that craving is highest early in the morning and falls as the day progresses (Chandra, Scharf, & Shiffman, 2008). Consequently, we contrasted the first assessed morning cigarette of the day with subsequent cigarettes, expecting that the latter would show lower craving.

Recent studies of smoking behavior in real-world settings show that environmental smoking restrictions can influence the likelihood of smoking (e.g., Chandra, Shiffman, Scharf, Dang, & Shadel, 2007; Shiffman et al., 2002). Accordingly, we assessed the influence of smoking restrictions (coded as forbidden, discouraged, or allowed) on craving across the smoking situations analyzed in this study.

Although previous analyses of real-time data from Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA; Stone & Shiffman, 1994) have not demonstrated an association between affect and ad libitum smoking (i.e., outside the context of a quit attempt; Shiffman et al., 2002; Shiffman & Paty, 2006), we also examined the relationship between affect and craving, because negative affect has been shown to be an important factor in relapse (Shiffman, 2005; Shiffman & Waters, 2004) and has a prominent role in theories of smoking (e.g., Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004). Similarly, research suggests that cigarette craving associated with positive affect is experienced by smokers who are not trying to quit (Baker, Morse, & Sherman, 1987).

Methods

Participants were 394 heavy smokers who participated in a smoking cessation study, for which clinical data are reported elsewhere (Shiffman, Ferguson, & Gwaltney, 2006; Shiffman, Scharf, et al., 2006). Individuals were recruited via local advertisements for a cessation research program. Briefly, inclusion criteria (detailed in Shiffman, Scharf, et al., 2006) were as follows: participants were 21–65 years of age, smoked 15+ cigarettes per day (CPD), had smoked for 5 or more years, reported general good health, and had a strong desire to quit. Individuals were excluded if a medical screening determined them unsuitable for high-dose nicotine replacement therapy. All participants worked regular daylight hours; shift workers were excluded. Informed consent was obtained prior to enrollment, and participants were compensated $50 in addition to free behavioral treatment. All participants expressed high motivation and confidence to quit smoking (defined as a total of ≥150 sum of two 100-point scales).

Participants (n = 394) averaged 39.26 (SD = 9.55) years of age; 84.26% were Caucasian (15.74% Black) and 48.98% male. On average, participants were moderately dependent (e.g., Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence [FTND]: M = 5.89, SD = 1.96; Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale [NDSS] total score: M = −0.06, SD = 0.88), had been smoking for 21.91 (SD = 9.63) years, and reported smoking 23.87 (SD = 9.13) CPD. Out of a possible 12 days of data, the average participant contributed 11.31 (SD = 1.55) days; 82% of participants completed the entire baseline period (i.e., through target quit day [TQD]). About 10% of participants (n = 42) contributed less than 7 days of baseline data prior to dropping out. These individuals did not differ significantly (nonsignificant; P > .10) from individuals who contributed at least 7 days of data on any nicotine dependence (FTND, Heatherton et al., 1991; NDSS, Shiffman, Waters, & Hickcox, 2004) or demographic measures, including age, gender, ethnicity, weekly alcohol use, and so forth.

Procedure

Data used in the current study were taken from the baseline period leading up to a quit day. During this baseline period, participants were instructed to smoke as usual. After being trained to use the electronic diary (ED), participants were instructed to continue smoking ad libitum for 2 weeks, without changing their smoking frequency or pattern up until the TQD on the 17th day. We focus on ad libitum smoking during Days 3–15 of this baseline period. We excluded Days 1 and 2 to allow for acclimation to the study and Day 16 for being too close to the quit day. Participants were instructed to record each cigarette on the ED, immediately before smoking; the ED randomly selected approximately five of these smoking occasions per day for assessment. Assessments, lasting approximately 1–3 min, consisted of a series of questions pertaining to craving and to the situation, the participant’s activity, and mood at the time. Questions were presented on-screen one at a time and always included prompts indicating the context being assessed (in this case, “before cigarette”) and the topic being assessed (e.g., “what were you doing?”). At the beginning of the study, participants were trained on the use of the ED and also on the meaning and interpretation of the questions.

The ED system hardware was a PalmPilot Professional palmtop computer. Software for data collection was developed specifically for this study (invivodata, inc., Pittsburgh, PA). In an earlier study, Shiffman (2009) validated self-monitoring of smoking on ED using both biochemical measures and time line follow-back self-reports (Sobell, Maisto, Sobell, & Cooper, 1979). Analyses based on cigarette entries preceding a carbon monoxide measurement also suggested that participants entered cigarettes in a timely way. Participants responded within 2 min to >90% of randomly timed audible prompts that ED issued 4–5 times daily (Shiffman & Kirchner, 2009), suggesting excellent compliance with the protocol.

Clinic visits were scheduled on Days 2, 7, and 14 to ensure participant compliance and to provide treatment. Participants met in groups of 8–16 smokers for two sessions of group cognitive–behavioral treatment for smoking cessation prior to the TQD (Days 7 and 14). The sessions provided psychoeducation and support (e.g., Brown, 2003) and were run by doctoral students in clinical psychology. A half-day trial abstinence period during which participants were instructed to briefly attempt abstinence occurred on Day 9 (Shiffman, Ferguson, et al., 2006); accordingly, we excluded that day from analysis.

Measures

At baseline, participants reported a variety of demographic measures, including age, years of education, gender, income, ethnicity, years smoking, and smoking rate. They also completed the FTND (Heatherton et al., 1991), and the NDSS (Shiffman et al., 2004).

Each time they smoked, participants recorded this on ED. On approximately five randomly selected smoking occasions per day, ED administered an assessment of craving and situational variables.

Craving

Craving was assessed (the prompt was “Rate cigarette craving”) on a single Visual Analog Scale (VAS) with anchors at either end: 0 = “no craving,” 10 = “maximum craving.” Despite the limitations of single-item scales (see Sayette et al., 2000; Tiffany, Carter, & Singleton, 2000), this assessment was deemed well suited for an EMA study; a single item allows the measure to reflect craving at the particular moment of the report, to minimize the intrusiveness of the report itself, and to decrease the probability that completing the measure will impact the reported craving level (Sayette et al., 2000). Moreover, in a prior study (Shiffman et al, 2002), where both “craving” and “urge” were assessed, the two correlated r = .80, demonstrating very high reliability for the single items. That is, since reliability is the upper limit of validity, the reliability of each must be at least .80 to achieve the correlation of .80 (see Wanous, Reichers, & Hudy, 1997).

Situations

Situational variables were treated as binary—present or absent—in the analyses. Subjects reported any smoking restrictions in the place that they first decided to smoke. In cases where they had changed locations in order to smoke, they were also asked about restrictions in the location in which they actually smoked. All other variables referred to the situation where they first decided to smoke. Throughout this section, the actual text for questions assessing the smoking situation is included in parentheses along with a description of the situational variable.

Subjects’ reports of smoking restrictions (“Smoking regulations—Smoking allowed? Forbidden, Discouraged, Allowed”) were dichotomized by comparing episodes in which smoking was “forbidden” or “discouraged” to those in which smoking was “allowed.” Because smoking restrictions may influence smoking behavior (Chandra et al., 2007; Shiffman et al., 2002) and covary with other situational variables (e.g., being at work), we controlled for the presence of restrictions in all subsequent analyses.

In examining social setting (“Were you with others? No, With others, Others in view”), situations in which people were alone were contrasted with situations in which they were around others. When people reported they were not alone, we compared being with others in a group with others simply being in view. We also examined the effect of others smoking in the participant’s environment on craving (“Were others smoking? Yes, No”). As these two questions were asked independently, the data do not indicate whether or not the others who were smoking were part of the subject’s “group.”

With regard to location (“Where were you? Home, Workplace, Bar/restaurant, Others’ home, Vehicle, Outside, Other”), we examined two particular contrasts. We contrasted home versus workplace because the two jointly accounted for the vast majority of smoking occasions (73.24%) and because they represented distinct environments. Whereas home is conventionally a less structured and more relaxed environment in which individuals can typically establish their own rules, the workplace is structured and subject both to explicit smoking regulations and to behavioral and social controls by others (coworkers and employers). We also contrasted bar/restaurant environments to all other contexts because bars and restaurants have traditionally been havens for smoking (smoking was not legally banned in bars and restaurants at the time of the study).

In addition, we examined food and drink consumption within 15 min of smoking (“What were you doing? Eat (15 min)?, Drink?, Yes, No”). Subjects who reported drinking were asked whether they had consumed alcohol or coffee/tea (“Alcohol? Yes, No”; “Coffee/tea?, Yes, No”). Drinking alcohol was compared with doing anything else (controlling for drinking anything at all). The same approach was taken with caffeinated drinks.

With regard to activity (“What were you doing? Work?, Chores?, Leisure?, Interacting with others?, Inactive?, Yes, No”), we contrasted work and leisure activities, the two largest domains of activity, which differ substantially in level of psychological/physical demand on the person. We also compared being engaged in activity with being inactive (which was defined as any of the following: being between activities, waiting, or “doing nothing”) because there is some evidence to suggest that inactivity may facilitate smoking (Shiffman et al., 2002), perhaps out of boredom, rather than craving.

Indices of positive affect, negative affect, and arousal were constructed from ratings of adjectives (happy, content, calm, frustrated, irritable, miserable, sad, worried, spacey, hard to concentrate, tired, energetic, arousal/energy level) on a VAS scale (scaled 0–10), with anchors at the extremes (e.g., “Calm? 0 _ NO!!, 10 _ YES!!”). Confirmatory factor analysis (Ferguson, Shiffman, & Gwaltney, 2006), conducted on all individual observations (both baseline and postquit), established a factor solution for the affective adjectives, with scores for negative affect, positive affect, and arousal. All scales were estimated as standardized factor scores (M = 0, SD = 1).

Data analysis

Mixed modeling (SAS Proc-Mixed, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to compare mean craving levels between different smoking situations (e.g., work vs. home). These analyses accommodate datasets in which participants contribute a large and variable number of observations across time by creating a hierarchical two-level structure and separating variance between subjects and between occasions within subjects (Blackwell, Mendes de Leon, & Miller, 2006). Unstructured and spatial power covariance structures were used for modeling between- and within-subject levels, respectively. Random effects were specified to allow for variation in the effect of the predictor across participants and thus avoid potential overestimation of statistical significance (Schwartz & Stone, 2007).

For the affect variables, which were continuous, we examined curvilinear as well as linear relationships. Certain models of affect (i.e., circumplex model of affect; Russell, 1980) identify emotions as the combination of an affective and arousal state (i.e., anger reflects high negative affect and high arousal, while depression reflects high negative affect and low arousal). Consequently, we also examined interactions between affective dimensions.

Some of the analyses were hypothesis driven, as indicated in the paper’s introduction. Others were exploratory, which was considered appropriate for this initial study of craving in different real-world smoking situations.

Results

Does craving vary across smoking occasions?

In total, we examined 20,871 smoking episodes, an average of 59.01 (SD = 13.94) per participant. Average craving across all smoking episodes was 7.36 (SD = 0.07). Craving varied slightly more across smoking occasions within participants (53.60% of the variance observed) than between participants (46.40%). Across nearly all situations examined, the full range of craving scores (0–10) was observed. A few smoking episodes (n = 55; contributed by 25 participants) were associated with craving ratings of 0. Craving for most cigarettes (87.91%, n = 18,348) fell within the higher craving range of 6–10.

People reported changing locations to smoke on 6,254 occasions (29.9% of smoking occasions). Considering the smoking regulations in the context in which participants decided to smoke (before they moved), situations were about equally split between those where smoking was allowed (48.99%) and where it was discouraged (51.02%). In 81% of these cases, smoking was allowed in the locations where participants actually smoked.

Does craving vary with situational characteristics?

Results are summarized in Table 1. When smoking was “forbidden” or “discouraged” (22.76% of occasions), craving was 0.17 points higher (p < .0001) than when smoking was allowed; results were the same when comparing “forbidden” situations with “allowed.” Controlling for whether or not individuals moved to smoke and whether smoking was restricted when they decided to smoke did not affect these results. All other analyses controlled for the presence of smoking restrictions.

Table 1.

Differences in craving by situational variables

| Predictor |

Mean craving |

|||||

| Predictor category (vs. contrast category) | Predictor category | Contrast category | B | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | p value |

| Discouraged or forbidden (vs. allowed) | 7.53 | 7.36 | 0.170 | 0.098 | 0.242 | <.0001** |

| Work (vs. home) | 7.39 | 7.36 | 0.033 | −0.057 | 0.123 | .47a |

| Bar/restaurant (vs. other locations) | 7.38 | 7.40 | −0.017 | −0.135 | 0.101 | .78 |

| Inactive (vs. active) | 7.30 | 7.37 | −0.074 | −0.147 | −0.002 | .045* |

| Engaged in work or chores (vs. leisure) | 7.38 | 7.31 | 0.074 | 0.016 | 0.132 | .013* |

| Eating or drinking (vs. not eating or drinking) | 7.60 | 7.34 | 0.263 | 0.177 | 0.348 | <.0001** |

| Eating (vs. not eating) | 7.54 | 7.33 | 0.208 | 0.143 | 0.273 | <.0001** |

| Drinking (vs. not drinking) | 7.43 | 7.33 | 0.106 | 0.051 | 0.161 | <.001** |

| Drinking caffeine (vs. not drinking caffeine) | 7.33 | 7.32 | 0.009 | −0.071 | 0.089 | .82b |

| Drinking alcohol (vs. not drinking alcohol) | 7.28 | 7.31 | −0.075 | −0.182 | 0.114 | .65b |

| First morning cigarette report (vs. all others) | 7.47 | 7.34 | 0.125 | 0.059 | 0.191 | <.001** |

| Social smoking predictors | ||||||

| Interacting with others (vs. not interacting) | 7.36 | 7.39 | −0.028 | −0.086 | 0.030 | .34c |

| With others (vs. alone) | 7.39 | 7.34 | 0.052 | 0.003 | 0.101 | .036* |

| Others in group (vs. others in view) | 7.40 | 7.24 | 0.155 | 0.060 | 0.250 | <.001** |

| Other people smoking (vs. no others smoking) | 7.40 | 7.38 | 0.006 | −0.060 | 0.072 | .86 |

| Others smoking × others in group/view (interaction) | – | – | 0.045 | −0.123 | 0.214 | .60 |

| Others in group and other people smokingd | 7.39 | 7.47 | −0.085 | −0.159 | −0.010 | .026* |

| Others in view and other people smoking | 7.30 | 7.33 | −0.032 | −0.233 | 0.169 | .75 |

Note. Unless otherwise noted, controlling for smoking restrictions did not significantly change the results.

When controlling for restrictions, effect no longer significant.

Controlling for drinking.

Controlling for presence of others.

Others smoking only denotes whether or not any other people were smoking; does not differentiate whether others smoking were in one’s group or in view.

*p < .05; **p < .01.

Subjects reported similar levels of craving for cigarettes smoked at home versus at work. Nor was craving affected by interacting with others or being at a bar/restaurant. With regard to drinking alcohol or being at a bar or restaurant, results did not change when we limited the analysis to participants who reported smoking while drinking alcohol during the study (n = 170).

Craving was 0.05 points higher when participants were with other people versus when alone (p < .05) and was 0.16 points higher when people were with others in a group versus only with others in view (p < .001). Overall, craving was similar whether or not others were smoking nearby or whether the participant was in a group with others or simply had others in view. Nor was there a significant interaction between these two variables. Craving was 0.07 points lower for cigarettes smoked when people were inactive (vs. active; p < .05) and was also 0.07 points lower when people were smoking while engaged in leisure activities (vs. work; p < .05). Craving was 0.26 points higher for cigarettes smoked while consuming food or drink (p < .0001). When food and drink consumption were analyzed separately, both had a similar effect on craving individually (eating vs. not: p < .0001; drinking vs. not: p < .001). Drinking alcohol or caffeinated beverages was unrelated to craving.

Finally, craving was 0.125 points higher (p < .001) for the first assessed morning cigarette (average time of assessment: about 8:30 a.m.) than those smoked later on (average time of assessment: about 4:15 p.m.).

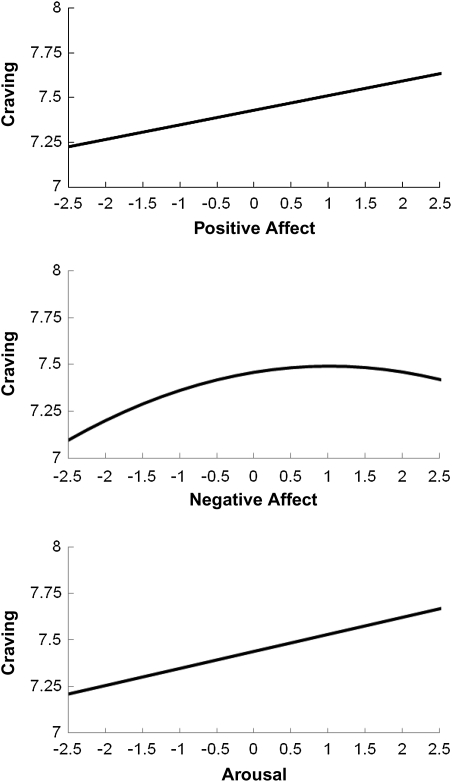

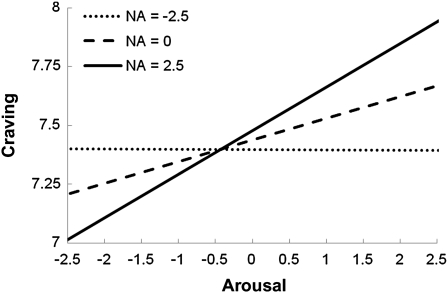

Affective correlates of craving are summarized in Table 2. Negative affect had a curvilinear relationship with craving, such that craving rose with negative affect up to a value of 1.0 (1 SD above the mean) and then decreased thereafter (p < .01; see Figure 1). In contrast, there was a positive linear relationship between craving and positive affect (p < .0001; see Figure 1) and craving and arousal (p < .0001; see Figure 1). There was an interaction between negative affect and arousal, such that negative affect was associated with greater increases in craving when arousal was high (p < .01; see Figure 2).

Table 2.

Affective predictors of craving

| Predictor | B | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | p value |

| NA linear | 0.040 | −0.0008 | 0.081 | .06 |

| Quadratic | −0.038 | −0.065 | −0.011 | <.01** |

| PA linear | 0.098 | 0.056 | 0.14 | <.0001** |

| Quadratic | 0.024 | −0.005 | 0.054 | .11 |

| PA × NA | −0.022 | −0.051 | 0.006 | .12 |

| AR linear | 0.093 | 0.066 | 0.12 | <.0001** |

| Quadratic | 0.015 | −0.006 | 0.036 | .16 |

| AR × PA | 0.003 | −0.021 | 0.028 | .79 |

| AR × NA | 0.037 | 0.013 | 0.060 | .002** |

Note. AR = Arousal; NA = Negative Affect; PA = Positive Affect.

**p <. 01; *p < .05.

Figure 1.

Negative affect, positive affect, and arousal predict cigarette craving based on modeled regression curves.

Figure 2.

Negative affect (NA) interacts with arousal to predict cigarette craving. Lines indicate relationship between arousal and craving at three values of NA, based on regression model.

Discussion

This study is the first to examine variation in craving within real-world smoking situations, and we found that cigarettes smoked in some situations are craved more strongly than those smoked in others. Indeed, there was at least as much variance in craving across occasions within individuals as there was between persons. However, the differences in craving that could be attributed to situational variables were consistently small on an absolute scale: less than 0.5 on a 0–10 scale. This is not surprising since craving was generally high when people were smoking. Nonetheless, the findings suggest that craving is affected by situational cues in real-world smoking situations, much as it is in the laboratory, when people are not smoking (e.g., Carter & Tiffany, 1999; Conklin, 2006; Shadel, Niaura, & Abrams, 2001).

The finding that cigarettes smoked in situations when smoking was discouraged or forbidden were associated with higher craving relative to those smoked in unrestricted situations (when smoking was allowed) was anticipated. This likely does not reflect the influence of the situation on craving, but rather the “selection pressure” exerted by smoking restrictions. People may wait longer to smoke when restrictions are in effect, leading to an increase in craving over time. Indeed, smoking restrictions do appear to suppress smoking (Chandra et al., 2007; Shiffman et al, 2002), but some high-craving cigarettes may “break through” these restraints, causing the familiar phenomenon of smokers moving elsewhere to smoke or—on rare occasions—smoking in restricted settings. This suggests that restrictions may concentrate smoking to occasions when craving is highest, which could increase opportunities for conditioning of craving. This would have significant implications for individuals attempting cessation, especially given the increasing trend toward public smoking restrictions, which result in these “outlaw” cigarettes being smoked in particular settings (e.g., outside buildings).

Given the potential for smoking restrictions to covary with other situational variables, and the relatively robust relationship between smoking restrictions and craving while smoking, we anticipated that smoking restrictions would account for some apparent variations in craving across other types of situations. For example, although craving levels were lower for cigarettes smoked at home relative to those smoked at work, controlling for smoking restrictions eliminated this difference. Similarly, Shiffman et al. (2002) showed that individuals were more likely to smoke at home than at work, but that restrictions were largely responsible for a decrease in likelihood of smoking at work. Moreover, our findings suggest that the absence of restrictions at home is associated with freer smoking, which may result in cigarettes being smoked even when craving intensity is relatively modest. That is, absent any restraint, the craving threshold for smoking may be low. Of note, home smoking bans are becoming more common (McMillen, Winickoff, Klein, & Wietzman, 2003), so these differences may be fading.

In a broader context, smoking restrictions may also influence craving through smokers’ expectations that smoking is possible or available as an option. Smoking cues seem to have a greater effect on craving when the smoker perceives that an opportunity to smoke is available (e.g., Carter & Tiffany, 2001). This would imply a potential interaction between smoking cues and smoking restrictions. However, because our data deal only with occasions when a cigarette was actually being smoked, cigarettes were presumably always “available,” so this would have played no role in the craving variations analyzed here. More generally, that availability was consistently high may suggest that our data were well suited for examining any differences in craving that may have arisen across situations.

Cigarettes smoked when individuals were with other people were associated with higher craving than cigarettes smoked when participants were alone. Craving was also higher when people were in a group with others they knew than when strangers were simply in view. However, there was no main effect of others smoking and no interaction of others smoking with the type of social setting (i.e., others in group vs. others in view). Although Piasecki, McCarthy, Fiore, and Baker (2008) report that exposure to others smoking is associated with more frequent reports of cigarette urge, and many cue reactivity studies have used images of others smoking to induce craving in the laboratory (e.g., Bauman & Sayette, 2006; Carter et al., 2006), our results suggest that an individual’s craving is actually higher when smoking simply occurs when others are present, whether they are smoking or not. It is possible that the presence of other people may make the individual more conscious of his smoking; such self-consciousness may trigger an awareness of craving that would not otherwise occur when alone (Tiffany, 1990). It is also possible that the presence of others (especially, perhaps, others who are not smoking) somewhat suppresses smoking, so that a higher threshold of craving must be reached before smoking is initiated. Future studies should examine the influence of social situations and others’ smoking on craving and smoking behavior in greater detail.

Craving was significantly higher for cigarettes smoked when participants were eating or drinking. This relationship was expected, as past research has found a high probability of smoking after eating (Shiffman et al., 2002), and smokers commonly report postprandial cigarette cravings (e.g., Jarvik, Saniga, Herskovic, Weiner, & Oisboid, 1989). Although the exact nature of the relationship between eating and smoking is still unclear (Lee, Jacob, Jarvik, & Benowitz, 1989), our findings suggest that high craving may play a role in initiating postprandial smoking.

The fact that drinking caffeine was not associated with a change in craving was surprising, as studies have shown a high correlation between smoking and drinking coffee (e.g. Istvan & Matarazzo, 1984), and there appear to be both pharmacological and psychological connections between nicotine and caffeine consumption (Kozlowski, 1976; Rose & Behm, 1991). While those studies document a relationship between caffeinated drinks and smoking, we saw no relationship with the intensity of craving accompanying that smoking.

Similarly, the fact that cigarettes smoked at a bar or restaurant or when drinking alcohol were not associated with higher craving, even when we limited the sample to smokers who reported drinking alcohol while smoking, was somewhat surprising. In a recent EMA study, Piasecki et al. (2008) reported that alcohol use was associated with more frequent reports of cigarette urge. However, differences between the two studies preclude direct comparison. In contrast to the present study, Piasecki et al. rated dichotomously whether a strong urge was present or absent, gathered data retrospectively, and did not characterize the timing of alcohol consumption, making it hard to compare the two studies.

Conklin (2006) noted that a bar/restaurant was one of the most common smoking situations reported by smokers, and previous analyses of EMA data (Shiffman et al., 2002) and laboratory studies (e.g., Burton & Tiffany, 1997; Sayette, Martin, Wertz, Perrott, & Peters, 2005) have shown that drinking is reliably associated with smoking. However, given the readiness with which people smoke in those settings (at least, before the advent of smoking bans that include bars and restaurants), they may not wait until craving is elevated, thus eliminating any differential in craving. Also, some stimuli, such as alcohol consumption, may trigger smoking automatically (e.g., Tiffany, 1990), that is, without stimulating craving as an intermediate precursor of smoking.

Time to first cigarette is an important marker of nicotine dependence (Baker et al., 2007). Our results are consistent with the literature on the importance of morning smoking, suggesting that cigarettes smoked early in the day are associated with higher craving, perhaps because of low nicotine blood levels after overnight abstinence (Jarvik et al., 2000).

Craving was higher when people were engaged in specific activities rather than being inactive (i.e., between activities, waiting, or “doing nothing”). Craving was also higher for cigarettes smoked when people were engaged in work or chores compared with those smoked when engaged in leisure. In other words, when people smoked while engaged in some form of work activity, these cigarettes were associated with higher craving. This may again be an effect of selection: People may only interrupt work to smoke when their craving is relatively elevated. Conversely, when they are inactive or at leisure, they may smoke readily, even at lower levels of craving, perhaps in response to boredom.

Historically, affect—specifically, negative affect—has been one of the most oft-cited situational triggers of smoking by smokers, and is frequently implicated as a cause of relapse during quit attempts (Cummings, Gordon, & Marlatt, 1980; Shiffman, 1982), even though EMA studies have not shown a relationship with smoking (Shiffman et al., 2002). Nevertheless, we expected an association between negative affect and craving. The association between negative affect and craving leveled off at the upper ranges of negative affect, suggesting that moderate negative emotion was enough to trigger craving and that craving did not continually increase as affect grew increasingly negative. Interestingly, in addition to there being a main effect of arousal on craving, craving was highest when both negative affect and arousal were elevated (i.e., there was a negative affect by arousal interaction). According to the circumplex model of affect (Russell, 1980), such states characterize emotions such as anxiety or anger. Some studies have demonstrated increased craving in response to stress manipulations (Perkins & Grobe, 1992; Tiffany & Drobes, 1990). Our results appear to be consistent with these findings.

Positive affect was also modestly associated with increases in cigarette craving while smoking (see Figure 1). This finding is consistent with a model in which appetitive-based “positive” urges are experienced during ad libitum smoking (vs. negative affect urges during deprivation; Baker et al., 1987). While previous cue reactivity studies have not shown an association between positive affect and increased cigarette craving (Drobes & Tiffany, 1997; Maude-Griffin & Tiffany, 1996), craving is typically assessed outside the context of actual smoking. Further work is needed to clarify the relationships between dimensions of emotion and craving. Nonetheless, these findings suggest that affective state may moderate craving, even if it does not moderate smoking itself.

A potential limitation of the present study was that participants were smokers who were preparing to quit. Besides limiting generalizability, this might have enhanced reactivity to monitoring, leading to reduced smoking. However, in a similar sample of heavy smokers preparing to quit, Shiffman et al. (2002) found only a slight decrease in reported ad libitum cigarette consumption (a drop of 0.3 CPD), and no change in carbon monoxide levels, suggesting any changes in actual consumption were modest. In addition, previous studies have shown only a modest increase in average cigarette craving (0.016 points per day on a 0- to 10-point scale) as smokers approach TQD (Dunbar, Scharf, Kirchner, & Shiffman, 2007). However, these studies cannot address whether patterns of smoking (as opposed to amount) and craving might be changed by reactivity due to monitoring or to impending cessation.

The study also had a number of strengths. The use of real-time, real-world EMA data allowed us to examine variations in craving outside the laboratory, as participants were actually smoking. Moreover, the large number of participants and smoking occasions provided considerable power for examining the relationship between craving intensity and different situational factors.

Because this study focused exclusively on situations where the person had elected to smoke, variability in craving was expected to be minimal. As the intensity of craving in smoking occasions generally fell within a narrow range, it is understandable that the observed variations in craving were small. Thus, the practical applications of these findings in a clinical setting may be limited. The magnitude of effects we observed may even be too small to be noticeable to smokers themselves. Nevertheless, they could exert some influence on later behavior and may be important in determining relative craving level or relapse risk in particular situations. As such, situational variations in craving when smoking deserve additional attention.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA06084). MSD received additional support from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program and partial support from the National Institute of Mental Health Undergraduate Fellowship in Mental Health Research at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (R-25 MH 54318-11-Haas).

Declaration of Interests

SS is cofounder of invivodata, inc., which provides electronic diary services for research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Joseph Stafura for comments on the paper.

References

- Baker TB, Morse E, Sherman JE. The motivation to use drugs: A psychobiological analysis of urges. In: Rivers C, editor. Nebraska Symposium on motivation. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1987. pp. 257–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Kim SY, et al. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: Implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(Suppl. 4):555–570. doi: 10.1080/14622200701673480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111(1):33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell E, Mendes de Leon CF, Miller GE. Applying mixed regression models to the analysis of repeated measures data in psychosomatic medicine. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:870–878. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000239144.91689.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman SB, Sayette MA. Smoking cues in a virtual world provoke craving in cigarette smokers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:484–489. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N. Psychoeducational groups: Process and practice. NewYork: Brunner-Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Burton SM, Tiffany ST. The effect of alcohol consumption on craving to smoke. Addiction. 1997;92:15–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BL, Robinson JD, Lam CY, Wetter DW, Tsan JY, Day SX, et al. A psychometric evaluation of cigarette stimuli used in a cue reactivity study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8:361–369. doi: 10.1080/14622200600670215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BL, Tiffany ST. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction. 1999;94:327–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BL, Tiffany ST. The cue-availability paradigm: The effects of cigarette availability on cue reactivity in smokers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9:183–190. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Scharf D, Shiffman S. Craving and restlessness, but not negative affect, precede ad lib smoking and are reduced after smoking. 2008, February. Paper presented at the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, Portland, OR. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Shiffman S, Scharf D, Dang Q, Shadel W. Daily smoking patterns, their determinants, and implications for quitting. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:67–80. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin C. Environments as cues to smoke: Implications for human extinction-based research and treatment. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14:12–19. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings C, Gordon JR, Marlatt GA. Relapse: Prevention and prediction. In: Miller WR, editor. The addictive disorders: Treatment of alcoholism, drug abuse, smoking, and obesity. New York: Pergamon; 1980. pp. 291–322. [Google Scholar]

- Drobes DJ, Tiffany ST. Induction of smoking urge through imaginal and in vivo procedures: Physiological and self-report measures. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:15–25. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar MS, Scharf DM, Kirchner T, Shiffman S. Craving trajectories approaching target quit day are related to achievement of initial (24H) smoking abstinence. 2007, February. Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, Austin, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SG, Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ. Does reducing withdrawal severity mediate nicotine patch efficacy? A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1153–1161. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Istvan J, Matarazzo JD. Tobacco, alcohol, and caffeine use: A review of their interrelationships. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;95:301–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvik ME, Madsen DC, Olmstead RE, Iwamoto-Schaap PN, Elins JL, Benowitz NL. Nicotine blood levels and subjective craving for cigarettes. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2000;66:553–558. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvik ME, Saniga SS, Herskovic JE, Weiner H, Oisboid D. Potentiation of cigarette craving and satisfaction by two types of meals. Addictive Behaviors. 1989;14:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT. Effects of caffeine consumption on nicotine consumption. Psychopharmacology. 1976;47:165–168. doi: 10.1007/BF00735816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BL, Jacob P, Jarvik ME, Benowitz NL. Food and nicotine metabolism. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1989;33:621–625. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. Relapse prevention. New York: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Maude-Griffin P, Tiffany ST. Production of smoking urges through imagery: The impact of affect and smoking abstinence. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;4:198–208. [Google Scholar]

- McMillen RC, Winickoff JP, Klein JD, Weitzman M. US adult attitudes and practices regarding smoking restrictions and child exposure to environmental tobacco smoke: Changes in the social climate from 2000–2001. Pediatrics. 2003;112:55–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.1.e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Grobe JE. Increased desire to smoke during acute stress. British Journal of Addiction. 1992;87:1037–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb03121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, McCarthy DE, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Alcohol consumption, smoking urge, and the reinforcing effects of cigarettes: An ecological study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:230–239. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Behm FM. Psychophysiological interactions between caffeine and nicotine. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1991;38:333–337. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90287-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell J. A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;37:345–356. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Martin CS, Wertz JM, Perrott MA, Peters AR. The effects of alcohol on cigarette craving in heavy smokers and tobacco chippers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:263–270. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Shiffman S, Tiffany ST, Niaura RS, Martin CS, Shadel WG. Methodological approaches to craving research: The measurement of drug craving. Addiction. 2000;95:S189–S210. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JE, Stone AA. The analysis of real-time momentary data: A practical guide. In: Stone AA, Shiffman S, Atienza A, Nebeling L, editors. The science of real-time data capture: Self-reports in health research. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 76–113. [Google Scholar]

- Shadel WG, Niaura R, Abrams DB. Effect of different cue stimulus delivery channels on craving reactivity: Comparing in vivo and video cues in regular cigarette smokers. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2001;32:203–209. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(01)00035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Relapse following smoking cessation: A situational analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:71–86. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Dynamic influences on smoking relapse process. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:1715–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. How many cigarettes did you smoke? Assessing cigarette consumption by global report, time-line follow-back, and ecological momentary assessment. Health Psychology. 2009;28:519–526. doi: 10.1037/a0015197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Ferguson SG, Gwaltney CJ. Immediate hedonic response to smoking lapses; Relationship to smoking relapse, and effects of nicotine replacement therapy. Psychopharmacology. 2006;184:608–618. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH, Liu KS, Paty JA, Kassel JD, et al. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:531–545. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Jarvik ME. Smoking withdrawal symptoms in two weeks of abstinence. Psychopharmacology. 1976;50:35–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00634151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Kirchner T. Cigarette-by-cigarette satisfaction during ad libitum smoking. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:348–359. doi: 10.1037/a0015620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty J. Smoking patterns and dependence: Contrasting chippers and heavy smokers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:509–523. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Scharf DM, Shadel WG, Gwaltney CJ, Dang Q, Paton SM, et al. Analyzing milestones in smoking cessation: Illustration in a nicotine patch trial in adult smokers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:276–285. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ. Negative affect and smoking lapses: A prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:192–201. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters A, Hickcox M. The Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale: A multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:327–348. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Maisto LC, Sobell MB, Cooper AM. Reliability of alcohol abusers’ self-reports of drinking behaviors. Behavioral Research and Therapy. 1979;17:157–160. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;16:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST. A cognitive model of drug urges and drug-use behavior: Role of automatic and nonautomatic processes. Psychological Review. 1990;97:147–168. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.97.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Carter BL, Singleton EG. Challenges in the manipulation, assessment and interpretation of craving relevant variables. Addiction. 2000;95:S177–S187. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Drobes DJ. Imagery and smoking urges: The manipulation of affect content. Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15:531–539. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90053-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanous JP, Reichers AE, Hudy MJ. Overall job satisfaction: How good are single-item measures? Journal of Applied Psychology. 1997;82:247–252. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West RJ, Hajek P, Belcher M. Severity of withdrawal symptoms as a predictor of outcome of an attempt to quit smoking. Psychological Medicine. 1989;19:981–985. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700005705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.