Abstract

Introduction:

This study evaluated how well DSM-IV nicotine dependence symptoms measure an underlying dependence construct for recent-onset daily and nondaily smokers.

Methods:

Based on a nationally representative sample of 2,758 recent-onset adolescent smokers from the National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, we used multiple group item response theory analysis to assess 7 symptoms representing DSM-IV diagnostic features of nicotine dependence.

Results:

After controlling for age, gender, current smoking quantity, and length of smoking exposure, all 7 DSM-IV symptoms were invariant across nondaily and daily smokers and discriminated well among levels of the nicotine dependence construct. Symptoms most likely to be endorsed at lower levels of the dependence construct included spending more time getting, using, or getting over the effects of smoking and wanting or trying to stop or cut down. Symptoms most likely to be endorsed only at higher levels of the construct included giving up important activities and emotional/psychological and health problems related to smoking. DSM-IV symptoms were most precise for moderately high levels of the dependence construct and less precise for lower levels for both nondaily and daily smokers.

Discussion:

DSM-IV nicotine dependence symptoms appear to have desirable psychometric properties for measuring a nicotine dependence construct among recent-onset adolescent smokers at both daily and nondaily levels, providing justification for the use of these symptoms in a measure that aims to evaluate the full continuum of nicotine dependence severity in this population.

Introduction

The conventional description of the natural history of dependent smoking is that individuals try smoking in early to mid-adolescence and then gradually escalate their frequency of smoking over a 2- or 3-year period to the point of daily smoking. Daily smokers continue to escalate their cigarette use as they develop into chronic dependent smokers. Though this description is consistent with national survey data (Breslau, Johnson, Hiripi, & Kessler, 2001; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2002), it represents an average that does not convey the wide variety of patterns that occur during the emergence of nicotine dependence. More recent evidence based on studies of adolescent smokers has consistently shown that, for some adolescents, nicotine dependence symptoms emerge very soon after the onset of smoking and at low levels of nicotine exposure (Dierker et al., 2007; DiFranza, Savageau, Rigotti, et al., 2002; O’Loughlin et al., 2003).

With the exception of a few studies designed specifically to evaluate the emergence of nicotine dependence (DiFranza, Savageau, Fletcher, et al., 2002; DiFranza et al., 2000; O’Loughlin et al., 2003), symptoms have often been assessed only among respondents that meet clearly established smoking patterns (i.e., regular or daily use), thus constraining the range of smoking levels that can be examined and limiting the ability to consider dependence symptoms at lower levels of use. More recently, surveys of large nationally representative populations have substantially expanded inclusion criteria for the administration of nicotine dependence items allowing for more careful consideration of the early emerging aspects of dependence (Dierker & Donny, 2008; Kandel, Hu, Griesler, & Schaffran, 2007).

There are a number of measures of nicotine dependence symptoms. One of the most commonly used and extensively studied is the DSM-IV, which assesses seven criteria purported to assess the clinical features of dependence. The DSM-IV allows for a categorical diagnosis of the presence of nicotine dependence based on whether or not smokers meet any three of the seven criteria. Although DSM-IV has been most typically used to provide an overall diagnosis of nicotine dependence, there have been a few studies that have examined the DSM-IV at the symptom level. Strong and colleagues used item response theory (IRT) analysis to examine symptom characteristics in adolescents with psychiatric disorders (Strong et al., 2007) and established adult smokers (Strong, Kahler, Ramsey, & Brown, 2003). These studies suggest that some DSM-IV symptoms (e.g., tolerance in adults and smoking more after being unable to smoke for awhile in adolescents) appear to have a greater likelihood of endorsement at relatively low levels of nicotine dependence, whereas other symptoms (e.g., giving up activities to smoke in both adults and adolescents) are most likely to be endorsed at higher levels of dependence. Overall, these studies also suggest that DSM-IV symptoms are best at measuring dependence among individuals with higher levels of nicotine dependence. More recently, DSM-IV symptoms have been found to be related to an underlying continuum of nicotine dependence, suggesting that a categorical definition of dependence may ignore the underlying heterogeneity of nicotine dependence (Strong, Kahler, Colby, Griesler, & Kandel, 2009).

To date, however, differences in psychometric characteristics of DSM-IV symptoms related to smoking exposure have not been evaluated among novice adolescent smokers. It is not yet understood whether the DSM-IV symptoms typically used to assess dependence in more established daily smokers are suitable for assessing dependence in recent-onset nondaily smokers and whether the characteristics of these symptoms are similar for recent-onset smokers who have or have not reached daily smoking levels. It is improbable that infrequent nondaily smokers are nicotine dependent in the way that nicotine dependence is traditionally operationalized (Goedeker & Tiffany, 2008). Some dependence symptoms (e.g., tolerance and withdrawal) may be less relevant to the measurement of the underlying construct for these smokers than for daily smokers. However, research suggests that the symptoms experienced by novice smokers who smoke only occasionally predict smoking at heavier levels in the future (Dierker & Mermelstein, in press). If the relevance of dependence symptoms to the construct being measured differs, this suggests that the psychometric properties of the symptoms may also differ between nondaily and daily smokers. As a result, the underlying construct assessed by the same symptoms may mean different things depending upon one’s current level of smoking exposure. This can lead to problems in measurement of the construct as well as interpretation of its meaning. Consequently, it is important to establish whether these symptoms are suitable for measuring “dependence” in recent-onset smokers with varying levels of exposure. If the psychometric characteristics of nicotine dependence symptoms do in fact differ as a function of smoking exposure, these differences should be considered in measuring the dependence construct.

Symptoms may differ between adolescent nondaily and daily smokers in likelihood of endorsement and in ability to discriminate among individuals with different levels of the nicotine dependence construct. Evidence of such instability across population subgroups, referred to as differential item functioning (DIF), suggests that there are systematic differences in symptom properties among the population subgroups of interest, independent of underlying nicotine dependence. Observed differences between nondaily and daily smokers in the relations among scores on the nicotine dependence construct and other outcome variables may reflect DIF-related measurement bias instead of actual differences related to smoking exposure (Horn & McArdle, 1992; Meredith, 1993). Scores on the dependence construct that do not take into account variability in the psychometric properties of the symptoms are likely to be less accurate for population subgroups that differ on these properties.

The present study used an IRT approach to evaluate symptom level properties based on a nationally representative sample of 2,758 “recent-onset” adolescent smokers. Data were drawn from four annual National Surveys on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), one of the largest, nationally representative epidemiological studies available to date that includes substantial heterogeneity in adolescent nicotine exposure as well as assessment of nicotine dependence symptoms among adolescents as young as 12 years old. The aims of the study were to determine (a) likelihood of endorsement of individual DSM-IV symptoms at different levels on a latent nicotine dependence construct, (b) ability of individual symptoms to discriminate among adolescents with different levels of nicotine dependence on this construct, and (c) whether these symptom properties vary according to whether smokers are engaged in nondaily versus daily smoking behavior (i.e., DIF).

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of N = 2,758 individuals aged 12–21 years who reported smoking (a) at least once in the past month and (b) first exposure to smoking within the past 2 years. The NSDUH utilizes multistage area probability sampling methods to select a representative sample of the noninstitutionalized U.S. civilian population aged 12 years or older. Persons living in households, military personnel living off base, and residents of noninstitutional group quarters including college dormitories, group homes, civilians dwelling on military installations as well as persons with no permanent residence are included. The NSDUH oversamples adolescents aged 12–17 years to improve precision of substance use estimates.

Half the sample were women (49.6%) and 65% were between the ages of 12 and 17 years. The sample was largely non-Hispanic White (70%) with 13% non-Hispanic Black, 12% Hispanic, and 5% other ethnicity. The majority (N = 2,266, 80.2%) were nondaily smokers, and 20% had progressed to daily smoking within the 2 years following initiation, which is within the range of previous estimates of 17% (Kandel, Kiros, Schaffran, & Hu, 2004) and 25% (Gervais, O’Loughlin, & Meshefedjian, 2006) within 1–2 years. Most nondaily smokers (88.6%) smoked no more than five cigarettes on the days they smoked, whereas only 31.2% of daily smokers smoked no more than 5 cigarettes/day. Participants smoked an average of 13 of the past 30 days (SE = 0.37, range 1–30). Slightly fewer than half (43.2%) had been smoking for more than 1 but no more than 2 years, and the rest began smoking in the past year.

Measures

Smoking variables

Smoking exposure was assessed by frequency (how many days participants smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days), quantity (the average number of cigarettes participants smoked on the days that they smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days, dichotomized into no more than 5 vs. more than 5 cigarettes/day), and length of exposure (difference between age at which participants first reported smoking a cigarette and their current age, dichotomized into 1 year or less vs. between 1 and 2 years).

Nicotine dependence

Past year nicotine dependence was assessed in the 1995–1998 NSDUH with seven DSM-IV-based symptoms, including spending a great deal of time getting, using, or getting over effects of cigarettes, smoking more often or in larger amounts than intended, tolerance, use prevented participation in activities, emotional or psychological problems, health problems, and wanting or trying to quit or cut down. From 1995 to 1998, the NSDUH did not assess withdrawal, which precludes the ability to evaluate this symptom.

Analysis

We used IRT analysis to test the hypotheses. IRT analysis has the advantage of allowing us to examine differences in the probability of symptom endorsement among smokers engaged in daily versus nondaily smoking while controlling for level of the nicotine dependence construct and other covariates. We conducted multiple group two-parameter IRT analyses (using Mplus Version 5 software; L. K. Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2007) comparing nondaily and daily smokers to test whether the psychometric properties of symptoms along a single latent nicotine dependence construct differed among these groups (B. O. Muthen & Lehman, 1985) after controlling for age, gender, quantity smoked, and length of smoking exposure. Based on mounting evidence for a single primary nicotine dependence construct underlying symptoms (Courvoisier & Etter, 2008; Strong et al., 2009) and a preliminary exploratory factor analysis indicating that the majority of the common variance in the DSM-IV symptoms in the current sample was explained by a single factor (eigenvalues for first and second factors = 4.52 and 0.80, respectively; 64.6% of variance explained by the first factor), we assumed a single latent nicotine dependence construct.

IRT analysis provides estimates of each symptom’s difficulty (severity) and discrimination. Symptom severity is the value of the latent nicotine dependence factor (which has a mean of 0 and a SD of 1) at which the probability of symptom endorsement is .50 and is a function of the estimated symptom thresholds. Symptoms that have a higher probability of being endorsed at low levels on the latent nicotine dependence construct have lower severity values. The difference among severity parameters across groups can be interpreted in the same manner as small (0.20), medium (0.50), or large (0.80) effect sizes (Steinberg & Thissen, 2006). Symptom discrimination indicates which symptoms best differentiate among adolescents with different levels on the latent nicotine dependence construct. It is a function of the slope (factor loading) of the symptom where higher values indicate greater symptom discrimination. Finally, the item characteristic curve (ICC) is a plot of these parameters combined and is examined to simultaneously evaluate symptom severity and discrimination at different values of the latent nicotine dependence construct. Items that differ across groups in symptom severity and/or discrimination exhibit DIF. A symptom with DIF indicates that daily and nondaily smokers with the same level of latent nicotine dependence have a different probability of endorsing that symptom. DIF can be uniform (differing only in severity) or nonuniform (differing in both severity and discrimination). Uniform DIF suggests that symptoms that emerge at lower levels of the nicotine dependence construct may differ for nondaily smokers. Nonuniform DIF suggests that there are not only differences among groups in symptom severity but that the symptoms that are the strongest indicators of the underlying construct differ between nondaily and daily smokers. This could suggest differences in the meaning of the construct across the groups.

To identify symptoms with DIF, we conducted six multiple group IRT analyses where a model constraining the slope (discrimination) and threshold (severity) parameters for one symptom to be equal across groups (constrained model) was compared with an unconstrained model in which these parameters were free to vary for all symptoms, with the exception of a single anchor symptom (one that loads highly on the nicotine dependence construct in both groups and shows no evidence of DIF based on preliminary factor analysis), for which the parameters are constrained to be equal across groups (Stark, Chernyshenko, & Drasgow, 2006). A single anchor symptom is required to ensure a common metric across smoking groups on the underlying nicotine dependence construct. Although it is possible to specify more than one anchor symptom, DIF tests cannot be conducted for any symptom constrained to be equal across groups. Therefore, we used only the necessary single anchor symptom. Each of these models controlled for effects of age (12–17 vs. 18–21 years), gender, smoking quantity, and length of exposure on the nicotine dependence construct by including paths regressing the latent nicotine dependence factor onto these variables. An approximate chi-square difference test provides a p value for the difference in model fit between the constrained and unconstrained models. A significant p value indicates a significantly worse fit of the constrained model and provides evidence of DIF for the symptom being tested. We used the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to adjust for multiple significance tests (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995; Thissen, Steinberg, & Kuang, 2002). We made the a priori decision to interpret DIF for any symptom with an adjusted statistically significant p value and to provide effect sizes for these symptoms to show the magnitude of the difference.

In the last step, we tested a final multiple group IRT model in which all symptoms showing evidence of DIF in the individual IRT models described above were free to vary across groups. This final model was used to generate ICCs, to obtain effect sizes for differences in symptom severity, and to calculate an estimated maximum a posteriori (MAP) nicotine dependence factor score that takes into account each individual’s response pattern and differences in symptom IRT parameter estimates.

Results

Results indicated that the symptom parameters did not differ significantly between nondaily and daily smokers after controlling for age, gender, quantity smoked, and length of exposure. That is, there was no evidence of DIF across groups. Therefore, the final multiple group IRT model was one in which all seven symptom slopes (discrimination parameters) and thresholds (severity parameters) were constrained to be equal across nondaily and daily smoking. Fit indices for this final model were reasonable (Tucker–Lewis index = 0.97, comparative fit index = 0.97, and root mean square error of approximation = 0.04). In addition, the p value associated with the approximate change in chi-square for the final multiple group IRT model compared with the unconstrained model was not significant (p = .16), indicating that fit was not significantly affected by simultaneously constraining all symptoms. Gender was not significantly related to the nicotine dependence factor (p = .97). However, younger adolescents (B = .16), those who had been smoking for more than 1 year (B = .20) and those who smoked more cigarettes on the days they smoked (B = .68) had significantly higher scores on the dependence factor (all ps < .01).

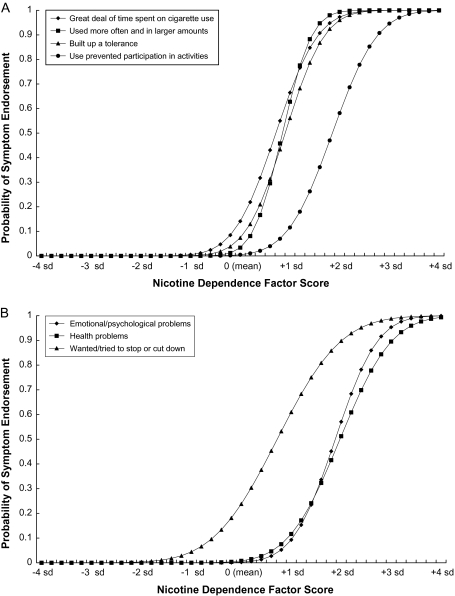

Table 1 shows severity and discrimination estimates from the final model, and Figure 1a and b show the symptom ICCs. Overall, symptoms discriminated among levels of the nicotine dependence construct fairly well, which suggests that they are all salient for this population of adolescents. Symptoms that best discriminated among levels of nicotine dependence (i.e., had the highest slope coefficients) included the following: (a) used cigarettes more often or in larger amounts (the anchor symptom); (b) tolerance; (c) spent a great deal of time getting, using, or getting over effects of smoking; and (d) cigarette use caused emotional or psychological problems. Wanting or trying to stop or cut down on cigarette use did not discriminate as well as the other symptoms.

Table 1.

Design adjusted symptom endorsement rates and item response parameter estimates

| Number (%) endorsing each symptom |

|||||

| Symptom | Nondaily | Daily | Discrimination (slope) | Severity (threshold) | Δχ2 p value |

| Spent great deal of time getting, using, or getting over effects of cigarettes | 752 (32.2) | 297 (66.45) | 1.24 | 0.81 | .668 |

| Used cigarettes more often or in larger amounts than intended | 608 (27.3) | 266 (58.3) | 1.67 | 0.96 | NA |

| Built up a tolerance so that same amount of cigarettes had less effect than before | 587 (25.8) | 247 (56.7) | 1.31 | 1.03 | 0.928 |

| Cigarette use kept you from working, going to school, taking care of children, or engaging in recreational activities | 186 (6.5) | 51 (11.8) | 1.17 | 2.10 | .038 |

| Cigarette use caused emotional or psychological problems | 176 (7.0) | 29 (6.6) | 1.24 | 2.13 | .028 |

| Cigarette use caused health problems | 201 (8.5) | 92 (21.3) | 1.03 | 2.25 | .247 |

| Wanted or tried to stop or cut down on your cigarette use | 736 (33.2) | 263 (58.4) | 0.85 | 0.82 | .301 |

Note. Item response estimates are from the final IRT model in which the severity and discrimination parameters were constrained to be equal across nondaily and daily smoking groups. The Δχ2 p value represents the p value for the change in chi-square between the model in which the discrimination and severity parameters were free to vary across groups (baseline model) and the model in which these parameters for the symptom of interest were constrained to be equal across groups. The Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple significance tests was used for all significance tests. NA = anchor item initially constrained to be equal across groups for model identification.

Figure 1.

(A and B) Item characteristic curves for DSM-IV symptoms (sd).

The symptom thresholds represent severity, the estimated level of the nicotine dependence construct at which each symptom is endorsed by 50% of the population of interest. Symptoms with low thresholds are more likely to be endorsed at lower levels on the nicotine dependence construct compared with other symptoms and are considered as having low severity. Overall, symptoms with the lowest severity included spent a great deal of time getting, using, or getting over effects of smoking and wanting or trying to stop or cut down. Conversely, symptoms with high thresholds, indicating low probability of endorsement at all but the highest levels on the nicotine dependence construct (high severity), included the following: use prevented participation in activities and emotional/psychological problems and health problems related to smoking.

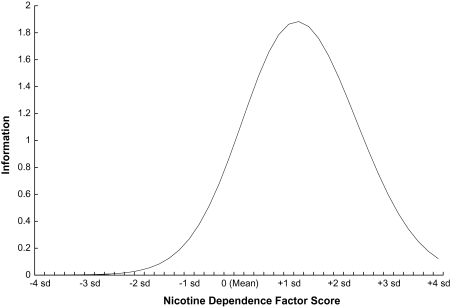

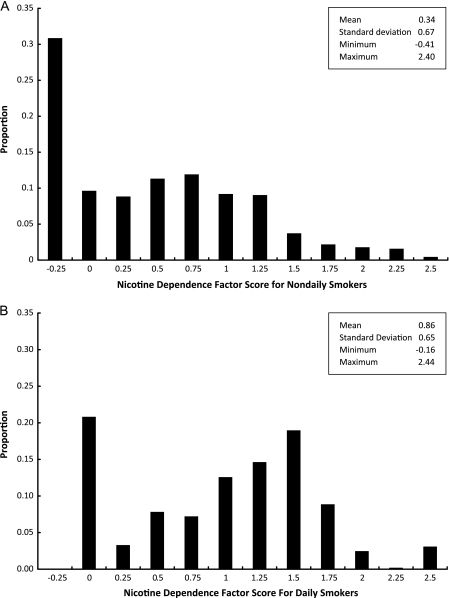

The total information curve for all seven DSM-IV-based symptoms (Figure 2) shows the amount of information in the underlying dependence construct explained by the symptoms across a range of levels on the construct. Higher levels of information indicate more precise measurement of the construct. The seven symptoms combined appeared most precise at measuring moderately high levels of the nicotine dependence construct (i.e., 1–2 SDs above the mean). The distribution of the MAP nicotine dependence factor score based on the final constrained IRT model for nondaily and daily smokers is shown in Figure 3. As expected, the distribution for nondaily smokers was skewed with the majority having low levels of the nicotine dependence construct. However, there was considerable variability among the scores, which ranged from −0.41 to 2.40. The distribution for daily smokers was shifted such that more individuals had higher levels of the dependence construct compared with nondaily smokers (ranging from −0.16 to 2.44).

Figure 2.

DSM-IV symptoms total information curve (sd).

Figure 3.

(A and B) Distribution of nicotine dependence factor scores for nondaily and daily smokers.

Discussion

Given the absence of a “gold standard” for measuring self-reported nicotine dependence, and interest in emergence of symptoms among novice smoker early in the uptake process and at low levels of smoking exposure (Colby, Tiffany, Shiffman, & Niaura, 2000; DiFranza et al., 2007; Kassel, Stroud, & Paronis, 2003; O’Loughlin, Tarasuk, DiFranza, & Paradis, 2002), there is a need to evaluate existing measures to determine how well symptoms measure the underlying nicotine dependence construct and whether individual symptoms function differently based on variability in smoking exposure among recent-onset smokers. Notably, the present findings revealed that all seven DSM-IV symptoms were invariant in terms of discriminating well between levels of nicotine dependence for both nondaily and daily smokers after controlling for age, gender, and smoking quantity, which indicates that these symptoms were strongly related to an underlying nicotine dependence construct across levels of smoking exposure. In addition, symptom severity was invariant across groups, which suggests that the ordering of these symptoms in terms of probability of endorsement at different levels of the nicotine dependence construct was similar for nondaily and daily smokers. Taken together, the demonstrated properties of these symptoms (precision of measurement and invariance across levels of smoking frequency) are highly desirable in terms of measurement development, and therefore, the DSM-IV symptoms appear well suited and may be justifiably included as part of self-report measures of a nicotine dependence construct among novice smokers with varying levels of smoking exposure.

Symptoms most likely to be endorsed at lower levels of the latent dependence construct included spending more time getting, using, or getting over the effects of smoking and wanting or trying to stop or cut down, suggesting that adolescents who may just be beginning to experience dependency have an increased focus on smoking, yet are already experiencing a desire to quit. On the other hand, symptoms more likely to be endorsed only at higher levels of latent nicotine dependence included interference with important activities and emotional/psychological and health problems related to smoking. Intuitively, adolescents with higher levels of dependence may be more likely to experience these symptoms and continue to smoke despite experiencing these negative consequences. These results provide some insight into which symptoms are most salient along a continuous nicotine dependence construct, which may prove important to targeting prevention efforts for adolescents whose level of dependence may vary regardless of their smoking frequency. Interventions targeting adolescents with lower levels of dependence might emphasize strategies to quit smoking because these adolescents seem to want to quit and may be most successful in their quit attempts given their lower levels of dependence. Prevention efforts targeted at adolescents with low levels of dependence might also focus on developing stricter regulations to further limit access to cigarettes. Interventions targeting adolescents with higher levels of dependence might focus on more intensive strategies to quit smoking that may include both cognitive and behavioral strategies focused on cessation as a way to improve both psychological and physical health and pharmacological support to maximize likelihood of successful cessation.

Consistent with past research (Strong et al., 2007, 2009), we found that symptoms based on the DSM-IV most precisely measure nicotine dependence for both nondaily and daily smokers with moderate to high scores on the dependence construct. Overall, nondaily smokers had lower scores on the dependence construct but displayed considerable variability. Notably, the symptom severity estimates appeared bimodal such that symptoms were likely to be endorsed either at about 1 SD above the mean on the dependence construct or at >2 SDs above the mean, but none had severity levels between +1 and +2 SDs. This may be due to the relative lack of endorsement of the symptoms with high severity (emotional or health problems related to smoking and interference with important activities) among these novice smokers. These symptoms may more likely to appear after smoking for a longer period of time. The lower rate of endorsement of the health problem symptom, in particular, might also suggest a lack power to detect DIF in this population. Improved self-report measures of an underlying nicotine dependence construct in recent-onset smokers might also include symptoms from other measures that are better suited for measuring lower to moderate levels of the dependence construct to ensure that the full continuum of dependence severity is represented. Recent research suggests that some symptoms from the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (Shiffman, Waters, & Hickcox, 2004) may be well suited for tapping lower levels of dependence (Strong et al., 2009).

A major strength of this study is that it involved a large nationally representative dataset, which allowed us to evaluate nicotine dependence symptoms in larger subgroups of nondaily and daily smokers than past research has allowed and to generalize more confidently to a broader population of recent-onset adolescent smokers. In addition, our study sought to identify DIF in nicotine dependence symptoms between nondaily and daily smokers controlling for important covariates such as gender, age, smoking quantity, and length of exposure.

Despite its strengths, some limitations should be noted. First, the NSDUH did not assess withdrawal, an important feature of dependence, precluding assessment of invariance of these symptoms across nondaily and daily smokers. Second, IRT analysis alone does not provide information about the predictive validity of dependence symptoms. Although recent research indicates that dependence symptoms predict future smoking behavior in novice smokers (Dierker & Mermelstein, in press; DiFranza, Savageau, Rigotti et al., 2002; Sledjeski et al., 2007), it is not likely that these symptoms are equally predictive of future smoking behavior. Additional research is required to determine which symptoms are most likely to predict future smoking. Third, the methods used in this study do not tell us about the mechanisms that underlie symptom endorsement. Symptom endorsement could reflect neurobiological consequences of nicotine use as well as other factors, such as history of major depression (Dierker & Donny, 2008) and delay discounting (Sweitzer, Donny, Dierker, Flory, & Manuck, 2008). Finally, we did not explore DIF in demographic subgroups.

Despite consistent ordering of symptoms, there is likely to be considerable variability in the pattern of endorsed symptoms both between and within nondaily and daily smoking groups. Assessing a nicotine dependence construct, particularly in novice adolescent smokers with varying symptom patterns and for whom the construct may have a different meaning, is challenging. This study provides justification for including DSM-IV symptoms in a measure that encompasses a wide range of symptoms tapping different aspects of smoking among novice adolescent smokers. IRT analysis does not specifically identify systematic differences in symptom endorsement patterns among these groups; however, this study provides support for a measurement approach that combines symptoms from different measures of nicotine dependence (Strong et al., 2009) and considers symptom variability as a way to improve our ability to measure this construct.

Funding

Financial support for the conduct of this research was provided by grants DA024260, DA15454, and DA022313 (LCD) and DA023459 (Donny) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, by a Center Grant (DA010075) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse awarded to the Methodology Center, Penn State University, and by awards from the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation and the Peter F. McManus Charitable Trust (LCD). These agencies had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing or review of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple significance testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hiripi E, Kessler R. Nicotine dependence in the United States: Prevalence, trends, and smoking persistence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:810–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SM, Tiffany ST, Shiffman S, Niaura RS. Are adolescent smokers dependent on nicotine? A review of the evidence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;59(Suppl. 1):S83–S95. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courvoisier D, Etter JF. Using item response theory to study the convergent and discriminant validity of three questionnaires measuring cigarette dependence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:391–401. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Donny E. The role of psychiatric disorders in the relationship between cigarette smoking and DSM-IV nicotine dependence among young adults. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:439–446. doi: 10.1080/14622200801901898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Donny E, Tiffany S, Colby SM, Perrine N, Clayton R, et al. The association between cigarette smoking and DSM-IV nicotine dependence among first year college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;86:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Mermelstein R. Early emerging nicotine dependence symptoms: A signal of propensity for chronic smoking behavior among experimental adolescent smokers. Journal of Pediatrics. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.11.044. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, Ockene JK, Savageau JA, St Cyr D, et al. Initial symptoms of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:313–319. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, Ockene JK, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, et al. Measuring the loss of autonomy over nicotine use in adolescents: The DANDY (Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youths) study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:397–403. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, Pbert L, O’Loughlin J, McNeill AD, et al. Susceptibility to nicotine dependence: The Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youth 2 Study. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e974–e983. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Rigotti NA, Fletcher K, Ockene JK, McNeill AD, et al. Development of symptoms of tobacco dependence in youths: 30 month follow up data from the DANDY study. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:228–235. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.3.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais A, O’Loughlin J, Meshefedjian G. Milestones in the natural course of onset of cigarette use among adolescents. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2006;175:255–261. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedeker KC, Tiffany ST. On the nature of nicotine addiction: A taxometric analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:896–909. doi: 10.1037/a0013296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn JL, McArdle JJ. A practical and theoretical guide to measurement invariance in aging research. Experimental Aging Research. 1992;18:117–144. doi: 10.1080/03610739208253916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Hu M, Griesler P, Schaffran C. On the development of nicotine dependence in adolescence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91:26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Kiros G.-E., Schaffran C, Hu M.-C. Racial/ethnic differences in cigarette smoking initiation and progression to daily smoking: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:128–135. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Stroud LR, Paronis CA. Smoking, stress, and negative affect: Correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:270–304. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W. Measurement invariance, factor analysis, and factorial invariance. Psychometrika. 1993;58:525–543. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen BO, Lehman J. Multiple group IRT modeling: Applications to item bias analysis. Journal of Educational Statistics. 1985;10:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5th ed. Los Angeles: Author; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- O’Loughlin J, DiFranza J, Tyndale RF, Meshefedjian G, McMillan-Davey E, Clarke P, et al. Nicotine-dependence symptoms are associated with smoking frequency in adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25:219–225. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Loughlin J, Tarasuk J, DiFranza J, Paradis G. Reliability of selected measures of nicotine dependence among adolescents. Annals of Epidemiology. 2002;5:353–362. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00312-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results From the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Volume I. Summary of National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NHSDA Series H-17, DHHS Publication No. SMA 02-3758). Rockville, MD.: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ, Hickcox M. The Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale: A multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:327–348. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledjeski EM, Dierker LC, Costello D, Shiffman S, Donny E, Flay BR. Predictive validity of four nicotine dependence measures in a college sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark S, Chernyshenko OS, Drasgow F. Detecting differential item functioning with confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory: Toward a unified strategy. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91:1292–1306. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Thissen D. Using effect sizes for research reporting: Examples using item response theory to analyze differential item functioning. Psychological Methods. 2006;11:402–415. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong DR, Kahler CW, Abrantes AM, MacPherson L, Myers MG, Ramsey SE, et al. Nicotine dependence symptoms among adolescents with psychiatric disorders: Using a Rasch model to evaluate symptom expression across time. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:557–569. doi: 10.1080/14622200701239563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong DR, Kahler CW, Colby SM, Griesler PC, Kandel D. Linking measures of adolescent nicotine dependence to a common latent continuum. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;99:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong DR, Kahler CW, Ramsey SE, Brown RA. Finding order in the DSM-IV nicotine dependence syndrome: A Rasch analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;72:151–162. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweitzer MM, Donny EC, Dierker LC, Flory JD, Manuck SB. Delay discounting and smoking: Association with the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence but not cigarettes smoked per day. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:1571–1575. doi: 10.1080/14622200802323274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Steinberg L, Kuang D. Quick and easy implementation of the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for controlling the false positive rate in multiple comparisons. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2002;27:77–83. [Google Scholar]