Abstract

The purpose of this study was to systematically review and summarize prehospital and in-hospital stroke evaluation and treatment delay times. We identified 123 unique peer-reviewed studies published from 1981 to 2007 of prehospital and in-hospital delay time for evaluation and treatment of patients with stroke, transient ischemic attack, or stroke-like symptoms. Based on studies of 65 different population groups, the weighted Poisson regression indicated a 6.0% annual decline (p<0.001) in hours/year for prehospital delay, defined from symptom onset to emergency department (ED) arrival. For in-hospital delay, the weighted Poisson regression models indicated no meaningful changes in delay time from ED arrival to ED evaluation (3.1%, p=0.49 based on 12 population groups). There was a 10.2% annual decline in hours/year from ED arrival to neurology evaluation or notification (p=0.23 based on 16 population groups) and a 10.7% annual decline in hours/year for delay time from ED arrival to initiation of computed tomography (p=0.11 based on 23 population groups). Only one study reported on times from arrival to computed tomography scan interpretation, two studies on arrival to drug administration, and no studies on arrival to transfer to an in-patient setting, precluding generalizations. Prehospital delay continues to contribute the largest proportion of delay time. The next decade provides opportunities to establish more effective community based interventions worldwide. It will be crucial to have effective stroke surveillance systems in place to better understand and improve both prehospital and in-hospital delays for acute stroke care.

Keywords: acute stroke therapy, CT scan, neurology, stroke, tPA, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Annually an estimated 15 million people worldwide suffer a stroke, resulting in 5 million deaths and another 5 million with permanent disability (1). Over the next decade, the stroke burden is projected to rise, particularly in developing countries (2). Timely access to effective medical treatment will be an important element to combat this public health challenge. Acute therapies for stroke, such as tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was approved more than 10 years ago (3, 4), emphasizing the need for rapid assessment of stroke patients. There was early hope that this new treatment would benefit many stroke patients, but this promise has yet to be realized. For example, over a decade later only 1% of stroke patients in the US received tPA from 1999 to 2002, although this may be an underestimate (5).

With the passing of a decade since tPA was granted approval for use in ischemic stroke patients, an assessment of progress towards more rapid access to diagnostic and treatment for stroke is warranted. This study systematically reviewed and summarized studies of time delay in prehospital and in-hospital evaluation and treatment, by updating our prior review of studies through the year 2000 (6). This review is an effort to understand changes over time and to provide insight for future research and practice directions.

METHODS

We conducted this systematic review using the same methods as described in our previous review (6), initially performed through March 2000. All published journal articles which reported on prehospital or in-hospital delay time for acute stroke care, including intervention studies, were included in this review. Abstracts, articles that were not peer reviewed, or dissertation works were not included. We also excluded studies that limited the description of delay time to aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, children, clinical trials, and studies limited only to patients receiving tPA.

A search was performed in two databases using subject headings and keywords, including studies published through December 2007. First, in the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE) the following search was performed: explode cerebrovascular disorders (medical subject heading) or stroke (keyword); explode emergency medical services (medical subject heading) or any form of delay (keyword); and combine the two with “and.” Second, in the Cumulated Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) the following search was performed: cerebral vascular accident (subject heading) or stroke (keyword); explode emergency medical services (subject heading) or treatment delay (subject heading) or any form of delay (keyword); and combine the two with “and”. For both MEDLINE and CINAHL, the search was limited to humans, age 19 years or older, and published in English. We also reviewed the references cited in each of published studies, which were identified through the search strategy, to capture any other potential studies for inclusion.

We extracted and report here only delay time related to total prehospital delay (e.g., onset of symptoms to hospital arrival) or in-hospital delays (e.g., time from emergency department (ED) arrival to ED physician evaluation, neurology evaluation, computed tomography (CT) scan or interpretation, tPA administration, and transfer to an in-patient setting, similar to those reported on the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) guidelines (7)). We do not, for example, describe components of prehospital delay, such as time from symptom onset to seeking medical help or time from calling emergency medical services (EMS) to arrival of either EMS or to the ED. For prehospital delay, we included the study if it reported a mean or median delay or a percent of the population arriving in so many hours. For in-hospital delay, we included the study if it reported a mean or median delay. In the summary tables provided, sample sizes are based on the number of patients with delay time reported and not on the initial study population size. If such a sample size was not given, we reported the initial study population size. If more than one article described results, we reported from the one with the larger sample size but reference both in the tables. Delay times were rounded off to the nearest tenth of an hour whenever possible. In some studies, means and medians were provided for samples of participants rather than for the whole sample and are therefore reported as such in the tables and summaries. For intervention studies, pre-test and post-test data are reported in the tables. If methodological information (e.g., dates) was missing from the primary reference, we examined a secondary reference cited in the primary publication to obtain the information where possible or we attempted to contact the lead author. The same two reviewers conducted data extraction from all included studies to ensure consistency and reliability.

All median delay times were graphed with the circle size proportional to the study sample. When a study was conducted over several years, we plotted the midpoint of the range in years. For studies not reporting the year of enrollment, we attempted to contact the authors to extract this information in order to plot the figures by year. If we still could not identify a date of the study, it was not included in the model or graphed. The Poisson model using the Pearson scale for over-dispersion provided an acceptable fit to the data, based on the ratio of the deviance to the degrees of freedom from the goodness-of-fit. A Poisson regression equation, unweighted and weighted by sample size, was calculated for median delay times across years using SAS (Cary, NC). Intervention studies were included only once (e.g., if both pre- and post-test medians were reported then only pre-test medians were graphed).

RESULTS

We report results first describing the update (2000 to 2007) since our prior review of the literature (6) that described studies published from 1981 through 2000, followed by a summary of the entire literature (1981 to 2007, labeled “Comprehensive Review Summary”) for prehospital and in-hospital delay times.

Prehospital Delay for Acute Stroke Care

Since our initial review (6) which included 48 unique studies through early 2000, at least 73 more unique reports on prehospital delay for acute stroke care were identified (Table 1). These studies were published through the year 2007 and included two studies (one published in 1997(8) and one in 1998(9)) not identified on the first review.

Table 1.

Mean and median prehospital stroke delay (symptom onset to emergency department arrival) and percent arriving in 3, 6, and 24 hours, in reverse publication year order, 2000-2007

| Study dates | Location | Population Reported On |

Delay in Hours: | Percent Arriving In: | Truncated Times in Hours |

Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | 3 hours | 6 hours | 24 hours | |||||

| 2004-2005 | Sydney, Australia | 100 S | 40 | Batmanian, 2007 (41) | |||||

| 3 mo period | Netherlands | 263 S | 6.1 | 2.6 | Boode, 2007 (27) | ||||

| 2001 | Italy | 4,936 I, H unit 6,636 I, H ward |

39 36 |

48 hrs | Candelise, 2007 (14) | ||||

| 1981-1982 1991-1992 2001-2002 |

Auckland, New Zealand |

1,030 S 1,305 S 1,423 S |

42 47 59 |

Carter, 2007 (77) | |||||

| 2004-2005 | Southern Taiwan | I29 I, TIA | 1.2 | 92 | 4 hrs | Chen, 2007 (10) | |||

| 2005 | Pisa, Italy | 258 S | 40 | Chiti, 2007 (78) | |||||

| 2004 | Singapore | 100 CI | 16.1 | 12 | 27 | 64 | De Silva, 2007 (25) | ||

| 1999-2005 | Germany | 26,319 S, ICH women |

25 | Foerch, 2007 (79) | |||||

| 27,095 S, ICH men |

26 | ||||||||

| 2005-2006 | 142 hospitals in 4 US states |

7,901 S, TIA | 2.0 | 48% in 2 hrs |

Frankel, 2007 (80) | ||||

| 1997-1998 | 10 European countries |

1,721 S | 43 | Heidrich, 2007 (81) | |||||

| 1993-1994 1999 |

Cincinnati, Ohio | 1,757 I 1,963 I |

23 26 |

Kleindorfer, 2007 (82) | |||||

| 2003-2006 | Warsaw, Poland | 733 I | 18% in 2 hrs |

Kobayashi, 2007 (83) | |||||

| 2000-2004 | Boston, Massachusetts |

106 I | 1.1 | 70 | 24 hrs | Konstantopoulos, 2007 (11) |

|||

| 2000-2005 | Southeast Texas | 2,257 I | 33 | 46 | 75 | Majersik, 2007 (84) | |||

| 2003-2004 | Munich and Regensburg, Germany |

23 BAO direct 16 BAO transfer |

2.1 1.5 |

1.3 1.0 |

Mu̇ller, 2007 (85) | ||||

| 2000-2006 | Switzerland | 876 I | 53 | 81 | 24 hrs | Nedeltchev, 2007 (12) | |||

| 2002-2005 | Szczecin, Poland | 1,015 I, H | 6.0 | 33 | Nowacki, 2007 (86) | ||||

| 1999 | Mu̇nster, Germany | 102 I | 35% in 2 hrs |

Ritter, 2007 (87) | |||||

| 2000-2001 | Chicago and Urbana/ Champaign, IL |

38 I | 27.7 | 16.0 | 34% in 2 hrs |

Zerwic, 2007 (88) | |||

| 2000-03 | Bern, Switzerland | 615 I, TIA | 6.3 | 3.0 | 51 | 62 | 48 | Agyeman, 2006 (15) | |

| 1998-2000 | Australia | 150 SS | 4.5 | 41 | 86 | Barr, 2006 (89) | |||

| 2002-03 | Oxfordshire, UK | 241 TIA | 56 | Giles, 2006 (90) | |||||

| 2004 | Kurashiki, Japan | 130 I, CH | 7.5 | (30 in 2 hrs) | Iguchi, 2006 (91) | ||||

| 2000-01 | 4 hospitals in Berlin, Germany |

588 I, H, TIA | 2.5 | 168 | Jungehulsing, 2006 (21) Rossnagel, 2004 (92) |

||||

| 2003 | Norway | 88 I | 23 | 31 | Owe, 2006 (53) | ||||

| 1998-2004 | Perugia, Italy | 2213 I, H, S | Yr 2000 Yr 2001 Yr 2002 Yr 2003 |

6.1 5.9 5.7 5.6 |

61 | Silvestrelli, 2006 (93) | |||

| 2001-02 | 98 hospitals in 4 US states |

6867 I, ICH, SAH, TIA |

GA (n=1450) MA (n=1206) MI (n=2566) OH (n=1608) |

21 27 19 23 |

34 41 33 35 |

61 68 53 61 |

Coverdell, 2005 (71) | ||

| 1999-2002 | Southwestern Ontario, Canada |

179 S LHS (n=109) RHS (n=70) |

1.2 1.2 |

Di Legge, 2005 (45) | |||||

| 2001-02 | Canadian Stroke Registry |

990 HS LHS (n=458) RHS (n=473) |

25 24 |

5.8 6.2 |

40 34 |

||||

| 1995-98 | 20 Portuguese hospitals |

90 CVT | 4 days | 25 | Ferro, 2005 (94) | ||||

| 1997-98 | Melbourne, Australia | 566 I, H, S=undetermined |

3.9 | 34 | 45 | 59 | Gilligan, 2005 (95) | ||

| 2003 | Charleston, West Virginia |

64 S | 14.3 | 4.1 | (34 in 2 hrs) | John, 2005 (96) | |||

| 2003-04 | Istanbul, Turkey | 229 I, H | 1.5 | 49 | 48 | Keskin, 2005 (16) | |||

| 1998-99 | Kaohsiung, Taiwan | 197 S, ICH | 5.3 | 48 | Li, 2005 (97); Chang, 2004 (17); Tan, 2002 (98) (median time taken from Li 2005 study) |

||||

| 2000-02 | Israel | 209 I | 15.3 | 4.2 | Mandelzweig, 2005 (99) | ||||

| 2000-01 | Berlin, Germany | 42 I; female with arrhythmia 154 I; female without arrhythmia 37 I; male with arrhythmia 221 I; male without arrhythmia |

1.4 3.3 2.5 2.6 |

Nolte, 2005 (100) | |||||

| 2000 | 11 hospitals in Western New York |

1590 I | 21 | 32 | 51 | Qureshi, 2005 (101) | |||

| 2002-03 | Hong Kong | 173 I, S 189 I, S |

9.7 8.4 |

30 32 |

Chow, 2004 (68) | ||||

| 1999-2000 | Cleveland, Ohio | 1635 I | 15 | Katzan, 2004 (102) | |||||

| 1999-2000 | 156 hospitals in Japan |

16922 I, TIA | 37 | 50 | 73 | 168 | Kimura, 2004 (22) | ||

| 2000-02 | Thessaloniki, Greece | 100 I, ICH, SAH, TIA |

3.2 | 45 | 71 | Koutlas, 2004 (38) | |||

| not known | 2 hospitals, Midwest US |

50 I, H, TIA | 5.5 | 5.0 | 29 | Maze, 2004 (103) | |||

| 2003-04 | 7 hospitals in rural Georgia |

62 I | 1.2 | 0.8 | Wang, 2004 (39) | ||||

| 2001 | Hartford, Connecticut | 64 I | 3.9 | 42 | 58 | Bohannon, 2003 (104) | |||

| 2000 | Newcastle on Tyne, UK |

356 CI, ICH, SAH |

49 | Harbison, 2003 (105) | |||||

| 2000-01 | 14 hospitals in Ohio | 604 I, H, TIA, S | 4.0 | 1.9 | 66 | 84 | >6 optional | Katzan, 2003 (24) | |

| 1998-99 | Sao Paulo, Brazil | 59 I, TIA, H | 18.8 | 29 | 32 | 53 | Leopoldino, 2003 (40) | ||

| 2000-02 | Bern, Switzerland | 597 I Bern Non-Bern−CT Non-Bern+CT |

1.7 2.1 3.5 |

1.4 2.3 3.5 |

Nedeltchev, 2003 (106) | ||||

| 1997-98 | Dublin, Ireland | 117 I | 16.0 | 33 | 56 | 87 | Pittock, 2003 (107) | ||

| 1997-2000 | Rural Florida and Georgia |

111 I helicopter transported |

71 | Silliman, 2003 (108) | |||||

| 1999-2000 | 6 hospitals in Houston, Texas |

359 SS | 3.8 | 1.6 | (59 in 2 hrs) | Wojner, 2003 (109) | |||

| 6 weeks, year not provided |

Heidelberg, Germany | 47 I, TIA (pre) | 5.2 | 2.3 | Behrens, 2002 (46) | ||||

| 71 I, TIA (post) | 3.3 | 1.4 | |||||||

| 1998-99 | Lyon, France | 164 I, ICH, SAH | 5.2 | 4.1 | 29 | 75 | Derex, 2002 (110) | ||

| 2000 | 22 hospitals in UK and Dublin, Ireland |

729 SS | 6.0 | 37 | 50 | Harraf, 2002 (28) | |||

| 2000 | 104 hospitals in Germany |

13440 I | 25 | Heuschmann, 2003 (72) | |||||

| 1998-2000 | 5 hospitals in Texas | 206 TIA, I, ICH, SAH 365 TIA, I, ICH, SAH |

8.4 3.7 |

(21 in 2 hrs) (30 in 2 hrs) |

Morgenstern, 2002 (57); Morgenstern, 2003 (61) | ||||

| 1999 | Edinburgh, Scotland | 42 SS | 10 | Quaba, 2002 (47) | |||||

| 2000 | Quezon City, Philippines |

259 I, ICH, SAH | 2.0 | 59 | 73 | 89 | 48 | Yu, 2002 (18) | |

| 1996-99 | 4 hospitals in Calgary, Canada |

1168 I | 27 | Barber, 2001 (111) | |||||

| 1994-95 | Germany | 222 IS | 25 | 48 | Becker, 2001 (56) | ||||

| 1997 | Hong Kong | 71 I, TIA, ICH | 20.6 | 4.0 | 56 | Cheung, 2001 (112) | |||

| 1997-98 | 3 locations in US | 559 SS | 47 | 48 | Evenson, 2001 (19) Schroeder, 2000 (29) |

||||

| 1998-99 | Durham, North Carolina |

506 I | 1998 1999 |

~17 ~6 |

~33 ~17 |

~63 ~56 |

Goldstein, 2001 (113) | ||

| 1999 | 42 ED in US | 511 I | Whites: 3.3 Blacks: 4.9 |

43 | Johnston, 2001 (114) | ||||

| 1996-97 | 10 ED in New Jersey | 553 SS | 46 | 61 | Lacy, 2001 (115) | ||||

| 1996-97 | 28 Indonesian hospitals |

2065 SAH, ICH, I |

98.8 | ~24 | 21 | 33 | 50 | Misbach, 2001 (26) | |

| 1997-98 | New Delhi, India | 110 S | 7.7 | 25 | 49 | 87 | 72 | Srivastava, 2001 (20) | |

| 1998-99 | Himeji, Japan | 254 I, TIA, IS | 32 | 40 | 70 | 168 | Yoneda, 2001 (23) | ||

| 1997 | 48 ED in US | 721 SS | 5.4 | 2.6 | 56 | 24 | Morris, 2000 (13) | ||

| 1997-99 | Germany | 64 I | 2.2 | 1.6 | Schellinger, 2000 (49) | ||||

| 22 months, year not provided |

Milan, Italy | 1068 S, TIA | 9.0 | 2.6 | 53 | Villa, 2000 (116) (update from Villa 1999 (117) on prior review) |

|||

| 1997 | Taipei, Taiwan | 842 S, CH, SAH, TIA |

38 | Yip, 2000 (118) | |||||

| 1996-97 | Mobile, Alabama | 152 S | 36 | Zweifler, 1998 (9) | |||||

| 1994-95 | 4 hospitals in Bejing, China |

833 I, ICH/SAH, CE, TIA Ischemic (n=591) ICH/SAH (n=242) |

24 18 37 |

35 28 54 |

61 54 77 |

de Wang, 1997 (8) | |||

Abbreviations:

BAO = basilar arterial occulsion, CE = cerebral embolism, CH = cerebral hemorrhage, CI = cortical infarcts, CT = computed tomography, CVT = cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis, ED = emergency department, H = hemorrhagic stroke, I = ischemic, ICH = intracerebral hemorrhage, IS = in-hospital stroke, L/R HS = left/right hemispheric stroke, n = number of patients, S = stroke, SAH = subarachnoid hemorrhage, SS = stroke-like symptoms, TIA = transient ischemic attack

Pre and post indicates before and after an intervention.

Please see methods section of paper for details on data abstraction.

These more recent 73 studies included patients worldwide from Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania (e.g., Australia, New Zealand), and South America. Inclusion criteria varied across the studies, including patients with hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke or both. Some studies also included patients with stroke-like symptoms or with transient ischemic attack (TIA). Only a few studies reported truncating the delay time in their analysis (e.g., excluding patients from the analysis with extreme delay time values); these truncated times included 4 hours (10), 24 hours (11-13), 48 hours (14-19), 72 hours (20), and 168 hours (21-23). Additionally, stroke patient enrollment was optional in a study by Katzan et al (24) for prehospital delay times greater than 6 hours. By not excluding extreme times in presentation, the stroke delay time may be affected if outliers occur in the distribution, especially for mean values. Thus, in Table 1 both means and medians are reported, as well as percent of patients arriving within 3, 6, or 24 hours. Among the studies of prehospital delay, the time from symptom onset to ED arrival ranged from a median of 0.8 hours to ~24 hours and a mean of 1.2 hours to 98.8 hours, although not all studies reported both. The 50th percentile of the median prehospital delays reported in Table 1 occurred between 3 and 4 hours and the percent arriving within 3 hours ranged from 6% to 92%.

Comprehensive Review Summary

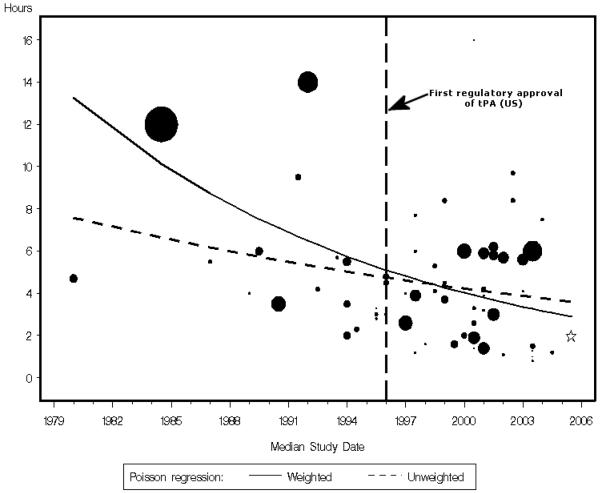

Figure 1 summarizes all published studies that reported a median prehospital delay time for acute stroke care since 1981. Studies that did not report a median delay time are not graphed. As evidenced by the size of the circles which are proportional to the sample size, only a few studies included more than 1000 patients. Based on the studies of 65 different populations, the weighted Poisson regression indicated an annual decline of 6.0% (model parameter −0.060 hours/year, p<0.001) and the unweighted Poisson regression indicated an annual decline of 2.9% (model parameter −0.029 hours/year, p=0.05). In the modeling, we did not include two outliers, studies with a median prehospital delay of 16.1 hours (25) and 24 hours.(26)

Figure 1.

Median prehospital delay time for stroke evaluation and care over time, with each study represented by a circle weighted for sample size

Note: Studies are plotted from either Table 1 of this paper or Table 1 from (6) if the study provided a median delay time. Two studies were not graphed because they represented outliers.(25, 26) Studies with missing enrollment dates (27, 46, 103, 116, 117, 119, 120) or sample sizes that corresponded to the median delay time reported (114) were excluded. The star represents a large study with a sample size of 7901 that did not fit on the plot (80) but was included in the model calculation.

In-hospital Delay for Acute Stroke Care

We identified fewer studies of in-hospital delay for acute stroke patients (25 unique papers since the year 2000) compared to our previous review (6). The studies published between 2000 to 2007 are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, examining the time from ED arrival to ED physician evaluation, neurology evaluation, CT scan or interpretation, and tPA administration. We did not identify any studies reporting on the time from arrival to transfer to an in-patient setting.

Table 2.

Mean and median in-hospital stroke delay in reverse publication year order, 2000-2007

| Study Dates |

Location | Population Reported On |

Time in Hours: |

Truncated Times in Hours |

Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | |||||

| Emergency Department Arrival to Emergency Physician Evaluation | ||||||

| 3 month period |

Netherlands | 263 S | 4.4 | 1.0 | Boode, 2007 (27) | |

| 2000-01 | 14 hospitals in Ohio | 692 I, H, TIA, S | 0.2 | >6 optional | Katzan, 2003 (24) | |

| 2000 | 22 hospitals in UK and Dublin, Ireland |

736 SS | 0.6 | Harraf, 2002 (28) | ||

| 1997-98 | 3 locations in US | 559 SS | 0.3 | 48 | Schroeder, 2000 (29) | |

|

Emergency Department Arrival to Neurology Notification or Evaluation | ||||||

| 2004-05 | Southern Taiwan | 129 I, TIA | 0.2 | 4 hrs | Chen, 2007 (10) | |

| 2004-05 | Melbourne, Australia |

187 I, TIA, ICH | 0.3 | Mosley, 2007 (36) | ||

| 2000-01 | 4 hospitals in Berlin, Germany |

558 I, H, TIA | 0.5 | 168 | Jungehulsing, 2006 (21) | |

| 2000 | Melbourne, Australia |

212 I, TIA (pre) | 0.7 | Bray, 2005 (37) | ||

| 210 I, TIA (post) | 0.4 | |||||

| 2003-04 | Istanbul, Turkey | 229 I, H | 0.4 | 48 | Keskin, 2005 (16) | |

| 2000-02 | Thessaloniki, Greece |

100 I, ICH, SAH, TIA |

0.3 | Koultas, 2004 (38) | ||

| 2003-04 | 7 hospitals in rural Georgia |

64 I | 1.0 | 0.9 | Wang, 2004 (39) | |

| 2000-01 | 14 hospitals in Ohio | 692 I, H, TIA, S | 0.2 | >6 optional | Katzan, 2003 (24) | |

| 1998-99 | Sao Paulo, Brazil | 59 I, TIA, H | 1.5 | Leopoldino, 2003 (40) | ||

| 2000 | Quezon City, Phillippines |

254 I, ICH, SAH | 7.5 | 48 | Yu, 2002 (18) | |

| 1997 | 48 ED in US | 615 SS | 3.1 | Morris, 2000 (13) | ||

| 1997-98 | 3 locations in US | 559 SS | 2.4 | 48 | Schroeder, 2000 (29) | |

|

Emergency Department Arrival to Initiation of CT Scan | ||||||

| 2004-05 | Sydney, Australia | 15 IS | 0.4 | Batmanian, 2007 (41) | ||

| 2004-05 | Southern Taiwan | 129 I, TIA | 0.3* | 4 hrs | Chen, 2007 (10) | |

| 2004 2005 |

Melbourne, Australia |

172 I, ICH, TIA (pre) 180 I, ICH, TIA (post) |

1.7 1.4 |

Hamidon, 2007 (42) | ||

| 2004 | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

171 SS | 1.7 | Chen, 2006 (43) | ||

| 2000-01 | 4 hospitals in Berlin, Germany |

558 I, H, TIA | 1.8 | 168 | Jungehulsing, 2006 (21) | |

| 2004 | Helsinki, Finland | 100 S | 0.1 | Lindsberg, 2006 (44) | ||

| 2000 | Melbourne, Australia |

212 I, TIA (pre) | 3.1 | Bray, 2005 (37) | ||

| 210 I, TIA (post) | 2.1 | |||||

| 1999-02 | Southwestern Ontario, Canada |

179 S LHS (n=109) RHS (n=70) |

0.9 0.8 |

Di Legge, 2005 (45) | ||

| 2000-02 | Thessaloniki, Greece |

100 I, ICH, SAH, TIA |

1.7 | Koutlas, 2004 (38) | ||

| 2000-01 | 14 hospitals in Ohio | 671 I, H, S | 1.1 | >6 optional |

Katzan, 2003 (24) | |

| 1998-99 | Sao Paulo, Brazil | 59 I, TIA, H | 5.3 | Leopoldino, 2003 (40) | ||

| 1999 | Heidelberg, Germany |

47 I, TIA (pre) | 1.3 | 1.1 | Behrens, 2002 (46) | |

| 71 I, TIA (post) | 1.2 | 1.1 | ||||

| 1999 | Edinburgh, Scotland |

57 SS | 2.2 days |

Quaba, 2002 (47) | ||

| 2000 | Quezon City, Philippines |

259 I, ICH, SAH | 5.5 | 48 | Yu, 2002 (18) | |

| 36% in 3 hr 53% in 6 hr |

||||||

| 1999-2000 | Southeastern Ontario, Canada |

42 I | 0.4 | Riopelle, 2001 (48) | ||

| 1998-99 | Himeji, Japan | 254 I, TIA, IS | 0.5 | 168 | Yoneda, 2001 (23) | |

| 1997 | 48 ED in US | 615 SS | 1.9 | 1.1 | 24 | Morris, 2000 (13) |

| 1997-99 | Germany | 64 I | 0.6 | 0.5 | Schellinger, 2000 (49) | |

| 1997-98 | 3 locations in US | 559 SS | 1.5 | 48 | Schroeder, 2000 (29) | |

|

Emergency Department Arrival to Expert CT Interpretation | ||||||

| 2000-01 | 14 hospitals in Ohio | 379 I, H, S | 1.7 | >6 optional |

Katzan, 2003 (24) | |

|

Emergency Department Arrival to tPA Administration | ||||||

| 2004-05 | Sydney, Australia | 15 IS | 1.5 | Batmanian, 2007 (41) | ||

| 2004 | Helsinki, Finland | 100 S | 0.8 | Lindsberg, 2006 (44) | ||

| 3 month period, year not provided |

Norway | 88 I | 1.3 | Owe, 2006 (53) | ||

| 1999- 2002 |

Southwestern Ontario, Canada |

179 S | Di Legge, 2005 (45) | |||

| LHS (n=109) | 1.4 | |||||

| RHS (n=70) | 1.4 | |||||

Pre and post indicates before and after an intervention, respectively.

Please see methods section of paper for details on data abstraction.

to completion of scan

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography, CVD = cerebrovascular disease, H = hemorrhagic stroke, I = ischemic, ICH = intracerebral hemorrhage, IS = in-hospital stroke, L/R HS = left/right hemispheric stroke, n = number of patients, S = stroke, SAH = subarachnoid hemorrhage, SS = stroke-like symptoms, TIA = transient ischemic attack, tPA = tissue plasminogen activator

Time to an Emergency Department Physician Evaluation

Only four studies published between 2000 and 2007 reported on acute stroke care times from ED arrival to ED physician evaluation (24, 27-29). These three studies reported median delays ranging from 0.2 to 1.0 hours.

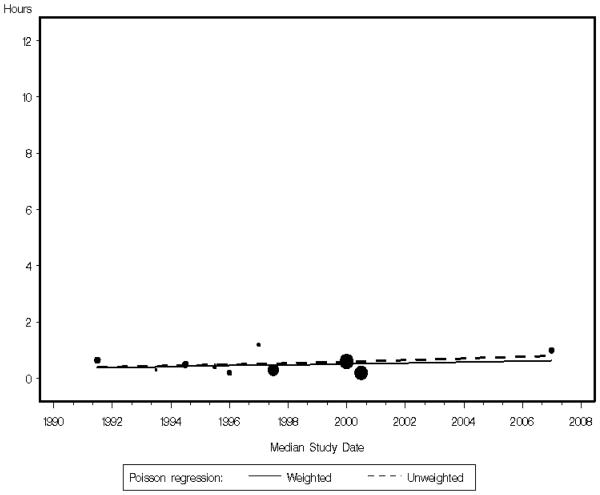

Comprehensive Review Summary

Overall, based on 10 studies (24, 27-35) of 12 different population samples with enrollment dating back to 1991, the weighted and unweighted Poisson regression calculating median study year by median time reported from ED arrival to ED evaluation indicated no decline, respectively (weighted model parameter 0.031 hours/year, p=0.49; unweighted model parameter 0.045 hours/year, p=0.25) (Figure 2a).

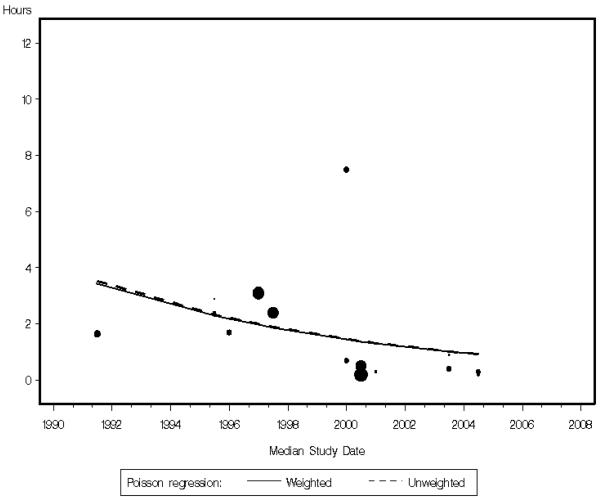

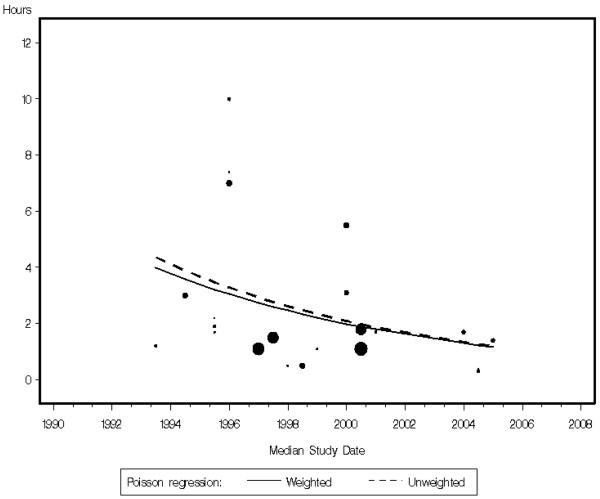

Figure 2.

Median in-hospital delay for stroke evaluation and care over time, with each study represented by a circle weighted for sample size.

a. Arrival to emergency physician evaluation

b: Arrival to neurology notification or evaluation

c: Arrival to initiation of computed tomography scan

Studies are plotted from either Table 2 of this paper or Table 2 from (6) if the study provided a median delay time.

For graph a, one study with missing enrollment dates was not graphed.(27) For graph c, the Cassidy et al study (52) was not graphed because the delay represented an outlier (48 hours).

Time to Expert Physician (Neurologist) Notification

Twelve unique studies (10, 13, 16, 18, 21, 24, 29, 36-40) published between 2000 and 2007 described acute stroke care time from ED arrival to neurology (defined as the expert physician) notification or evaluation. The median delay times for 10 of these studies ranged from 0.2 to 3.1 hours (10, 13, 16, 21, 24, 29, 36-39), with an additional study conducted in the Philippines reporting a median delay of 7.5 hours (18). The final study reported a mean rather than a median delay time (40). Definitions for neurology timing varied across studies, including time to neurology consultation, time neurologist is notified, and time seen by a neurologist.

Comprehensive Review Summary

Overall, based on 14 unique studies (10, 13, 16, 18, 21, 24, 29, 30, 32, 35-39) with 16 different populations with enrollment dating back to 1991, the weighted Poisson regression calculating median study year by median time from arrival to neurology notification or evaluation indicated a nonsignificant annual decline of 10.2% (model parameter −0.102 hours/year, p=0.23) and the unweighted Poisson regression indicated a nonsignificant annual decline of 10.4% (model parameter −0.104 hours/year, p=0.17) (Figure 2b).

Time to a CT Scan or Interpretation

Nineteen unique studies (10, 13, 18, 21, 23, 24, 29, 37, 38, 40-49) describe acute stroke care time from ED arrival to CT scan, published between 2000 and 2007. The median delay times ranged from 0.1 to 3.1 hours for 13 of 14 studies, (10, 13, 21, 23, 24, 29, 37, 38, 41-43, 46, 49) with an additional study conducted in the Philippines reporting a median delay of 5.5 hours (18). The remaining 5 studies reported a mean delay time rather than a median delay time (40, 44, 45, 47, 48).

Comprehensive Review Summary

Overall, based on the 19 studies of 23 different samples (10, 13, 18, 21, 23, 24, 29, 33-35, 37, 38, 41-43, 49-51), the weighted Poisson regression calculating median study year by median time from arrival to CT scan indicated an annual decline of 10.7% (model parameter −0.107 hours/year, p=0.11) and the unweighted Poisson regression indicated an annual decline of 11.3% (model parameter −0.113 hours/year, p=0.06) (Figure 2c). In the modeling, we did not include one outlier, a study reporting a median delay of 48 hours from ED arrival to CT scan (52).

Hospital Arrival to tPA Administration

Prior to the year 2000, no studies reported time from hospital arrival to tPA administration. Of the studies reviewed between 2000 and 2007, four (41, 44, 45, 53) reported this time. Two studies reported a mean time from ED arrival to tPA administration as 0.8 (44) and 1.4 hours (45); two other studies reported median times of 1.3 hours (53) and 1.5 hours (41).

DISCUSSION

We identified 123 unique studies reporting on prehospital and in-hospital delay to diagnosis and care for acute stroke have been published since 1981. These studies enrolled patients dating back to 1971 from more than 30 countries worldwide. Globally, we identified only one study from South America, conducted in Brazil.(40) Africa is the only continent not represented by this research, despite a significant rising number of deaths occurring there from stroke each year (1). For these worldwide studies of acute stroke, the majority of the delay to treatment continues to be attributable to the prehospital portion consistent with what others have reported (54).

Delay Time

Our summary indicates, using weighted Poisson regression, an annual decline in prehospital delay time of 6.0% percent based on the studies of 65 different populations, since the first study published in 1980 that reported a median prehospital delay for stroke patients. While this is a meaningful decline, as evidenced from Figure 1, this decline has slowed in more recent years for the published studies in our review. Studies published since the year 2000 reporting a median delay of symptom onset to ED arrival indicate that the 50th percentile for delay occurred between 3 and 4 hours. This relatively long delay time excludes many patients from being considered for tPA therapy and may contribute to longer subsequent in-hospital delays to full evaluation and care. Few studies explore how prehospital delay subsequently affects in-hospital delay times for stroke patients, especially given that these events are not independent of one another (13, 24).

For the in-hospital portion of delay, ED delays have not appreciably changed, but delays to provision of neurology evaluation (10.2% annual decline) and CT scan (10.7% annual decline) appear to have improved, although not reaching statistical significance. It should be noted that studies limited to only patients receiving tPA were excluded from our review, as we were interested in describing results from a broader population perspective, including all patients arriving at the hospital regardless of receipt of tPA. By including only studies of patients receiving tPA, the delay times reported would have been reduced by design, because of the time requirements of the drug, resulting in selection bias.

It is helpful to compare these in-hospital times against some standard or guideline. One approach would be to use as a benchmark the NINDS recommendations (7) published in 1996 that outline the following goals for acute stroke patients: 10 minutes from the hospital door to emergency physician evaluation, 15 minutes from the door to stroke team or expert physician notification (interpreted as a neurologist), 25 minutes from the door to initiation of the CT scan, 45 minutes from the door to expert CT interpretation, 60 minutes from the door to drug administration, and 3 hours or less from the door to transfer to an in-patient setting. Using these benchmarks applied to all studies we reviewed reporting median times, of 10 studies or 12 population groups no studies met the ED delay time of 10 minutes (24, 27-35). Two (10, 24) of 12 studies or 14 population samples reporting median delay times met the neurology delay time of 15 minutes (13, 16, 18, 21, 29, 30, 32, 35-39). Two more recent studies (10, 41), using their median delay time, met the 25 minutes goal from arrival to CT scan initiation, but not in 18 other studies reporting a median delay time (13, 18, 21, 23, 24, 29, 33-35, 37, 38, 42, 43, 46, 49-52). Only one study reported median time to CT interpretation (24), for which it was not met. Neither of the two studies (41, 53) reporting a median value fell within the 60 minute time recommendation from arrival to tPA administration. We did not identify any studies reporting on the time from arrival to transfer to an in-patient setting. From this, we conclude that few studies report that NINDS in-hospital goals (7) are being met based on median reported times. This review provides the times in Tables 1 and 2 and the prior paper (6), so comparisons to other guidelines, either established or yet to be written can be made.

We found that there is little standardization as to how delay components are defined and reported. Such inconsistency makes comparisons across studies and countries difficult. For example, “time to CT scan” could be interpreted as time transported to CT (such as defined in Katzan et al (24)), arrival at the CT, initiation of the CT scan, or completion of the CT. As another example, “time to stroke team evaluation” is often interpreted as time to the neurologist, especially in hospitals without stroke teams, although it is not clear if it was intended to be this way.

Intervention Studies

Several studies have evaluated the effect of smaller scale community-wide campaigns on stroke awareness, knowledge, and/or delay (55-63). In addition, system changes, such as professional education (37, 46, 55, 59, 60, 64, 65), altering emergency dispatch and transport protocols (66, 67), instigating an ED fee (68), creating a rapid ED assessment (41), and implementing a stroke code team or call system (42, 58, 64, 69) have been all evaluated in an effort to reduce delay in stroke evaluation and care during either the prehospital or the in-hospital phase. Even so, effective interventions targeting those at highest risk for stroke are still needed and it would be desirable if interventions and even observational description of these associations were driven by a theoretical framework.

Limitations of this Review

Summarizing the literature in this way poses several challenges. First, these conclusions are drawn from a variety of data sources, countries, time periods, and patient populations. The type of surveillance data truly needed to monitor these trends is only now becoming available (70) (examples include (71, 72)). As countries worldwide establish stroke-based surveillance systems with comparable data elements, a better interpretation of trends over time and comparisons within and across countries can be accomplished. Until then, we feel this review provides the best worldwide interpretation of these trends, through the use of peer-reviewed publications. Second, the case definition of stroke varied across studies, although the interest was always acute stroke. Occasionally, studies applied exclusions due to extreme prehospital delay times for acute stroke. These exclusions were also inconsistent, hampering direct comparisons across studies. Third, not all studies reported a median delay time. While some studies provided a mean, subject to outliers, a few studies only reported the percentage receiving care within a given number of hours. Fourth, the definition of symptom onset of stroke was not defined consistently across studies, particularly when the patient awoke with stroke symptoms. Fifth, information on whether or not each participating hospital was approved to provide tPA or had a transfer protocol to a hospital providing tPA treatment of ischemic stroke was not available across all studies. The inclusion of data from hospitals that were not approved to administer tPA for ischemic stroke may have lengthened both prehospital and in-hospital delay times. However, this review represents published delay times in a variety of settings. Finally, we included only peer reviewed studies; thus, we are unsure if these results reflect the broader population. All of these limitations should be considered when interpreting these results.

Reporting Suggestions

Making comparisons across studies would be greatly enhanced if standardization in definitions were established. We suggest that delay time be reported as both a mean and a median and noting if the delay times were truncated. Other suggestions for observational or surveillance studies include designating clear entry criteria into the study that can be replicated across countries and using a standardized method for determining onset time when the patient awoke with symptoms, such as the one developed by Rosamond et al (73). Missing information on key data elements can also hamper surveillance of studies of delay (19). Weintraub (74) suggests that legible records of stroke patients should reflect the time of onset, the time of workup completion, examination findings, the diagnosis and differential diagnosis as well as the proposed treatments (e.g., use or not of tPA), and informed consent. We concur with Katzan et al (24), suggesting placement of the data form in the ED record and developing a standard documentation sheet for stroke patients as part of their medical record.

Extensive work evaluating the different treatment-seeking delay phases in acute coronary syndromes can be useful to studies of delay in accessing acute stroke evaluation and care (54). These phases have been broken down into 1) symptom onset to decision to seek medical attention, 2) decision to seek medical attention to first medical contact, and 3) first medical contact to hospital arrival. We suggest that the initial phase could be defined even further to make the distinction between onset of stroke-like symptoms and recognition of those symptoms, by patient, family, or observer, as to being symptoms warranting medical attention. Sometimes the onset of symptoms may not correspond to the onset of recognition of the symptoms, with the former influencing the consideration of tPA therapy, if applicable, and the latter influencing the likely seeking of medical attention.

Though numerous studies examine factors associated with prehospital delays of acute stroke (54, 75), very few have examined these time phases involved in prehospital delay. In addition, it is known that prehospital delay for acute stroke care affects in-hospital delay (13, 24). Because the timing of these events are not independent, future studies should consider examining these factors simultaneously rather than separately as has traditionally been done. To do this, timing data will need to be collected for all phases of delay.

Conclusions

We found a decreasing trend in prehospital delay time for acute stroke patients, the time from onset of symptoms to hospital arrival. While time from hospital arrival to ED physician evaluation changed very little over time, there was suggestion that trends for the time from hospital arrival to CT scan and neurology evaluation may be declining. However, lack of standardization in data collection and measurement across studies made comparisons challenging. The data for the most clinically pertinent time span, that of onset of stroke symptoms to onset of tPA administration for treatment of ischemic stroke, where indicated and not contraindicated, have been seldom specifically collected, studied, or reported in observational studies. Quality improvement initiatives, such as the World Health Organization's stepwise approach to stroke (2, 76) or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registries (71), address in-hospital diagnostic and treatment care indicators, including those related to timely initiation of care. These and other programs promise to accelerate progress toward achieving established in-hospital delay time goals. These programs, however, currently do not directly address patient-oriented delay factors associated with care seeking behavior after symptom onset, which continue to be the major source of delay in accessing medical care for stroke. The next decade provides opportunities to establish more effective community based interventions worldwide. It will be crucial to have effective stroke surveillance systems in place to better understand and improve prehospital and in-hospital delays for acute stroke care.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Randi Foraker was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), NHLBI NRSA Training Grant No. 5-T32-HL007055-30.

Additional Contributions: The authors thank Fang Wen for help with the figures and Dr. Leslie Bunce for reviewing an earlier version of the paper.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Morris works at GlaxoSmithKline. GlaxoSmithKline has in the past, and likely will in the future, participate in clinical trials of agents for stroke. Dr. Morris is currently not directly involved in any clinical trials for stroke and the publication of this manuscript would not affect the authors or the institution's financial situation. There are no other financial disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization . In: The Atlas of Heart Disease and Stroke. 15 - Global Burden of Stroke. Mackay J, Mensah G, editors. Geneva, Switzerland: 2004. Accessed July 14, 2007 at http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/resources/atlas/en/: Report No.: ISBN 92 4 156276 5 Contract No.: Document Number|. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . NCD Surveillance: Stroke. Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. [updated 2008; cited September 22, 2008 at http://www.who.int/ncd_surveillance/ncds/strokerationale/en/]; Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss K, Food and Drug Administration . Letter to MD MacFarlane, Genentech, Inc. Rockville, MD: 1996. (Reference No. 96-0350). Dated June 18, 1996. Accessed August 1, 2007 at http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/appletter/1996/altegen061896l.pdf; Contract No.: Document Number|. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Food and Drug Administration P87-32. TPA Approval -- Blood Clot Dissolver. 1987 Sect. http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/NEW00191.html accessed August 1, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bateman B, Schumacher H, Boden-Albala B, et al. Factors associated with in-hospital mortality after administration of thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke patients: An analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 1999 to 2002. Stroke. 2006;37:440–6. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000199851.24668.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evenson K, Rosamond W, Morris D. Prehospital and in-hospital delays in acute stroke care. Neuroepidemiol. 2001;20:65–76. doi: 10.1159/000054763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Treatment of Acute Stroke, editor. Proceedings of a National Symposium on Rapid Identification and Treatment of Acute Stroke; Washington, D.C.. 1997 December 12-13; 1996. Accessed August 1, 2007 at http://wwwnindsnihgov/news_and_events/proceedings/strokeworkshophtm; [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Wang Z, Guo H, Zhang XY, Zhu H, Li YH, Zhou G. An observation on the time of hospital arrival and correct diagnosis with CT in acute cerebral stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1997;7:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zweifler R, Brody M, Graves G, et al. Intravenous t-PA for acute ischemic stroke: Therapeutic yield of a stroke code system. Neurology. 1998;50(2):501–3. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.2.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CH, Huang P, Yang YH, Liu CK, Lin TJ, Lin RT. Pre-hospital and in-hospital delays after onset of acute ischemic stroke --- a hospital-based study in southern taiwan. The Kaohsiung journal of medical sciences. 2007;23(11):552–9. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(08)70002-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konstantopoulos WM, Pliakas J, Hong C, et al. Helicopter emergency medical services and stroke care regionalization: measuring performance in a maturing system. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(2):158–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nedeltchev K, Schwegler B, Haefeli T, et al. Outcome of stroke with mild or rapidly improving symptoms. Stroke. 2007;38(9):2531–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.482554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris DL, Rosamond W, Madden K, Schultz C, Hamilton S. Prehospital and emergency department delays after acute stroke : The Genentech Stroke Presentation Survey. Stroke. 2000;31(11):2585–90. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.11.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Candelise L, Gattinoni M, Bersano A, Micieli G, Sterzi R, Morabito A. Stroke-unit care for acute stroke patients: an observational follow-up study. The Lancet. 2007;369(9558):299–305. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agyeman O, Nedeltchev K, Arnold M, et al. Time to admission in acute ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2006;37(4):963–6. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000206546.76860.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keskin O, Kalemoglu M, Ulusoy RE. A clinic investigation into prehospital and emergency department delays in acute stroke care. Med Princ Pract. 2005;14(6):408–12. doi: 10.1159/000088114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang K-C, Tseng M-C, Tan T-Y. Prehospital delay after acute stroke in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Stroke. 2004;35(3):700–4. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000117236.90827.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu RF, San Jose MCZ, Manzanilla BM, Oris MY, Gan R. Sources and reasons for delays in the care of acute stroke patients. J Neurol Sci. 2002;199(12):49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00103-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evenson KR, Rosamond WD, Vallee JA, Morris DL. Concordance of stroke symptom onset time: The Second Delay in Accessing Stroke Healthcare (DASH II) Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11(3):202–7. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srivastava A, Prasad K. A study of factors delaying hospital arrival of patients with acute stroke. Neurol India. 2001;49(3):272–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jungehulsing GJ, Rossnagel K, Nolte CH, et al. Emergency department delays in acute stroke - analysis of time between ED arrival and imaging. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13(3):225–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimura K, Kazui S, Minematsu K, Yamaguchi T. Analysis of 16,922 patients with acute ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack in Japan. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18(1):47–56. doi: 10.1159/000078749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoneda Y, Mori E, Uehara T, Yamada O, Tabuchi M. Referral and care for acute ischemic stroke in a Japanese tertiary emergency hospital. Eur J Neurol. 2001;8(5):483–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katzan IL, Graber TW, Furlan AJ, et al. Cuyahoga County operation stroke speed of emergency department evaluation and compliance with National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke time targets. Stroke. 2003;34(4):994–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000060870.55480.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Silva DA, Ong SH, Elumbra D, Wong MC, Chen CL, Chang HM. Timing of hospital presentation after acute cerebral infarction and patients' acceptance of intravenous thrombolysis. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 2007;36(4):244–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Misbach J, Ali W. Stroke in Indonesia: A first large prospective hospital-based study of acute stroke in 28 hospitals in Indonesia. J Clin Neurosci. 2001;8(3):245–9. doi: 10.1054/jocn.1999.0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boode B, Welzen V, Franke C, van Oostenbrugge R. Estimating the number of stroke patients eligible for thrombolytic treatment if delay could be avoided. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23(4):294–8. doi: 10.1159/000098330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harraf F, Sharma A, Brown M, et al. A multicentre observational study of presentation and early assessment of acute stroke. BMJ. 2002;325(7354):17–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7354.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schroeder EB, Rosamond WD, Morris DL, Evenson KR, Hinn AR. Determinants of use of emergency medical services in a population with stroke symptoms : The Second Delay in Accessing Stroke Healthcare (DASH II) Study. Stroke. 2000;31(11):2591–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.11.2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferro J, Melo T, Oliveira V, Crespo M, Canhao P, Pinto A. An analysis of the admission delay of acute strokes. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1994;4:72–5. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salisbury H, Banks B, Footitt D, Winner S, Reynolds D. Delay in presentation of patients with acute stroke to hospital in Oxford. QJM. 1998;91(9):635–40. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/91.9.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menon SC, Pandey DK, Morganstern LB. Critical factors in determining access to acute stroke care. Neurol. 1998;51:427–32. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kothari R, Jauch E, Broderick J, et al. Acute stroke: Delays to presentation and emergency department evaluation. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70431-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lannehoa Y, Bouget J, Pinel J, Garnier N, Leblanc J, Branger B. Analysis of time management in stroke patients in three French emergency departments: From stroke onset to computed tomography scan. Eur J Emerg Med. 1999;6(2):95–103. doi: 10.1097/00063110-199906000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris DL, Rosamond WD, Hinn AR, Gorton RA. Time delays in accessing stroke care in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(3):218–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosley I, Nicol M, Donnan G, Patrick I, Kerr F, Dewey H. The impact of ambulance practice on acute stroke care. Stroke. 2007;38(10):2765–70. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.483446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bray J, Martin J, Cooper G, Barger B, Bernard S, Bladin C. An interventional study to improve paramedic diagnosis of stroke. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005;9(3):297–302. doi: 10.1080/10903120590962382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koutlas E, Rudolf J, Grivas G, Fitsioris X, Georgiadis G. Factors influencing the pre- and in-hospital management of acute stroke - data from a Greek tertiary care hospital. Eur Neurol. 2004;51(1):35–7. doi: 10.1159/000075084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang S, Gross H, Lee SB, et al. Remote evaluation of acute ischemic stroke in rural community hospitals in Georgia. Stroke. 2004;35(7):1763–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000131858.63829.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leopoldino JFS, Fukujima MM, Silva GS, do Prado GF. Time of presentation of stroke patients in Sao Paulo Hospital. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2003;61(2A):186–7. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2003000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Batmanian JJ, Lam M, Matthews C, et al. A protocol-driven model for the rapid initiation of stroke thrombolysis in the emergency department. The Medical journal of Australia. 2007;187(10):567–70. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamidon BB, Dewey HM. Impact of acute stroke team emergency calls on in-hospital delays in acute stroke care. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14(9):831–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen EH, Mills AM, Lee BY, et al. The impact of a concurrent trauma alert evaluation on time to head computed tomography in patients with suspected stroke. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(3):349–52. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindsberg P, Happola O, Kallela M, Valanne L, Kuisma M, Kaste M. Door to thrombolysis: ER reorganization and reduced delays to acute stroke treatment. Neurology. 2006;67(2):334–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000224759.44743.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Di Legge S, Fang J, Saposnik G, Hachinski V. The impact of lesion side on acute stroke treatment. Neurology. 2005;65(1):81–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000167608.94237.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Behrens S, Daffertshofer M, Interthal C, Ellinger K, van Ackern K, Hennerici M. Improvement in stroke quality management by an educational programme. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13(4):262–6. doi: 10.1159/000057853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quaba O, Robertson CE. Thrombolysis and its implications in the management of stroke in the accident and emergency department. Scot Med J. 2002;47(3):57–9. doi: 10.1177/003693300204700304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riopelle RJ, Howse DC, Bolton C, et al. Regional access to acute ischemic stroke intervention. Stroke. 2001;32(3):652–5. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.3.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schellinger PD, Jansen O, Fiebach JB, et al. Feasibility and practicality of MR imaging of stroke in the management of hyperacute cerebral ischemia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(7):1184–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wester P, Radberg J, Lundgren B, Peltonen M, Seek-Medical-Attention-in-Time Study Group Factors associated with delay admission to hospital and in-hospital delays in acute stroke and TIA. Stroke. 1999;30(1):40–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Charleston A, Barber P, Bennett P, Spriggs D, Harris R, Anderson N. Management of stroke in Auckland Hospital in 1996. NZ Med J. 1999;112(1083):71–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cassidy T, Lewis S, Gray C. Computerised tomography and stroke. Scot Med J. 1993;38(5):136–8. doi: 10.1177/003693309303800503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Owe JF, Sanaker PS, Naess H, Thomassen L. The yield of expanding the therapeutic time window for tPA. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006;114(5):354–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moser D, Kimble L, Alberts M, et al. Reducing delay in seeking treatment by patients with acute coronary syndrome and stroke: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing and Stroke Council. Circ. 2006;114:175–89. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alberts M, Perry A, Dawson D, Bertels C. Effects of public and professional education on reducing the delay in presentation and referral of stroke patients. Stroke. 1992;23(3):352–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Becker K, Fruin M, Gooding T, Tirschwell D, Love P, Mankowski T. Community-based education improves stroke knowledge. Cerebrovas Dis. 2001;11:34–43. doi: 10.1159/000047609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morgenstern LB, Staub L, Chan W, et al. Improving delivery of acute stroke therapy: The TLL Temple Foundation Stroke Project. Stroke. 2002;33(1):160–6. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.101990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Malik M, Gomez C, Tulyapronchote R, Malkoff M, Bandamudi R, Banet G. Delay between emergency room arrival and stroke consultation. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 1993;3(3):177–80. doi: 10.1016/S1052-3057(10)80158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barsan W, Brott T, Broderick J, Haley E, Levy D, Marler J. Time of hospital presentation in patients with acute stroke. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2558–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barsan W, Brott T, Broderick J, Haley, Levy D, Marler J. Urgent therapy for acute stroke: Effects of a stroke trial on untreated patients. Stroke. 1994;25(11):2132–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.11.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morgenstern L, Bartholomew L, Grotta J, Staub L, King M, Chan W. Sustained benefit of a community and professional intervention to increase acute stroke therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2198–202. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.18.2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Silver FL, Rubini F, Black D, Hodgson CS. Advertising strategies to increase public knowledge of the warning signs of stroke. Stroke. 2003;34(8):1965–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000083175.01126.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hodgson C, Lindsay P, Rubini F. Can mass media influence emergency department visits for stroke? Stroke. 2007;38:2115–22. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.484071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zweifler R, Drinkard R, Cunningham S, Brody M, Rothrock J. Implementation of a stroke code system in Mobile, Alabama. Stroke. 1997;28:981–3. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.5.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lellis J, Brice J, Evenson K, Rosamond W, Kingdon D, Morris D. Launching online education for 911 telecommunicators and EMS personnel: Experiences from the North Carolina Rapid Response to Stroke Project. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2007;11(3):298–306. doi: 10.1080/10903120701348222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Culley L, Henwood D, Clark J, Eisenberg M, Horton C. Increasing the efficiency of emergency medical services by using criteria based dispatch. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1994;24(5):867–72. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(54)00223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harbison J, Massey A, Barnett L, Hodge D, Ford G. Rapid ambulance protocol for acute stroke. Lancet. 1999;353(9168):1935. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00966-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chow KM, Hui ACF, Szeto CC, Wong KS, Kay R. Hospital arrival after acute stroke: Any better after 10 years? Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;17(4):346. doi: 10.1159/000077953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gomez C, Malkoff M, Sauer C, Tulyapronchote R, Burch C, Banet G. Code stroke: An attempt to shorten inhospital therapeutic delays. Stroke. 1994;25(10):1920–3. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.10.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goff D, Jr., Brass L, Braun L, et al. Essential features of a surveillance system to support the prevention and management of heart disease and stroke. Circ. 2007;115:127–55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.The Paul Coverdell Prototype Registries Writing Group Acute Stroke Care in the US: Results from 4 Pilot Prototypes of the Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry. Stroke. 2005;36(6):1232–40. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000165902.18021.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heuschmann PU, Berger K, Misselwitz B, et al. Frequency of thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute ischemic stroke and the risk of in-hospital mortality: The German Stroke Registers Study Group. Stroke. 2003;34(5):1106–12. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000065198.80347.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosamond W, Reeves M, Johnson A, Evenson K, Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry Prototype Investigators Documentation of stroke onset time: Challenges and recommendations. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(6S2):S230–S4. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weintraub M. Thrombolysis (tissue plasminogen activator) in stroke: A medicolegal quagmire. Stroke. 2006;37:1917–22. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000226651.04862.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kwan J, Hand P, Sandercock P. A systematic review of barriers to delivery of thrombolysis for acute stroke. Age Ageing. 2004;33(2):116–21. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dalal P, Bhattacharjee M, Vairale J, Bhat P. Mumbai Stroke Registry (2005-2006) - Surveillance using WHO Steps Stroke Instrument - Challenges and Opportunities. J Assoc Physician India. 2008;56:675–80. Accessed at http://www.japi.org/september_2008/o_675.pdf. [PubMed]

- 77.Carter KN, Anderson CS, Hackett ML, Barber PA, Bonita R. Improved survival after stroke: Is admission to hospital the major explanation? Trend analyses of the Auckland Regional Community Stroke Studies. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23(23):162–8. doi: 10.1159/000097054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chiti A, Fanucchi S, Giorli E, Sonnoli C, Morelli N, Orlandi G. Thrombolysis for Acute Stroke: What about the Actual Impact on Patients Older Than 80 Years? Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;24(6):548. doi: 10.1159/000111224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Foerch C, Misselwitz B, Humpich M, et al. Sex disparity in the access of elderly patients to acute stroke care. Stroke. 2007;38(7):2123–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.478495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Frankel M, Kinchey J, Schwamm LH, et al. Prehospital and hospital delays after stroke onset--United States, 2005-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(19):474–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Heidrich J, Heuschmann PU, Kolominsky-Rabas P, Rudd AG, Wolfe CDA. Variations in the use of diagnostic procedures after acute stroke in Europe: results from the BIOMED II study of stroke care. European Journal of Neurology. 2007;14(3):255–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kleindorfer D, Broderick J, Khoury J, et al. Emergency department arrival times after acute ischemic stroke during the 1990s. Neurocritical Care. 2007;7(1):31–5. doi: 10.1007/s12028-007-0029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kobayashi A, Skowronska M, Litwin T, Czlonkowska A. Lack of experience of intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke does not influence the proportion of patients treated. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(2):96–9. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.040204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Majersik JJ, Smith MA, Zahuranec DB, Sanchez BN, Morgenstern LB. Population-based analysis of the impact of expanding the time window for acute stroke treatment. Stroke. 2007;38(12):3213–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.491852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Muller R, Pfefferkorn T, Vatankhah B, et al. Admission facility is associated with outcome of basilar artery occlusion. Stroke. 2007;38(4):1380–3. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000260089.17105.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nowacki P, Nowik M, Bajer-Czajkowska A, et al. Patients' and bystanders' awareness of stroke and pre-hospital delay after stroke onset: perspectives for thrombolysis in West Pomerania Province, Poland. Eur Neurol. 2007;58(3):159–65. doi: 10.1159/000104717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ritter MA, Brach S, Rogalewski A, et al. Discrepancy between theoretical knowledge and real action in acute stroke: self-assessment as an important predictor of time to admission. Neurological research. 2007;29(5):476–9. doi: 10.1179/016164107X163202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zerwic J, Hwang SY, Tucco L. Interpretation of symptoms and delay in seeking treatment by patients who have had a stroke: exploratory study. Heart Lung. 2007;36(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Barr J, McKinley S, O'Brien E, Herkes G. Patient recognition of and response to symptoms of TIA or stroke. Neuroepidemiol. 2006;26(3):168–75. doi: 10.1159/000091659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Giles MF, Flossman E, Rothwell PM. Patient behavior immediately after transient ischemic attack according to clinical characteristics, perception of the event, and predicted risk of stroke. Stroke. 2006;37(5):1254–60. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217388.57851.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Iguchi Y, Wada K, Shibazaki K, et al. First impression at stroke onset plays an important role in early hospital arrival. Intern Med. 2006;45(7):447–51. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rossnagel K, Jungehulsing GJ, Nolte CH, et al. Out-of-hospital delays in patients with acute stroke. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44(5):476–83. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Silvestrelli G, Parnetti L, Tambasco N, Corea F, Capocchi G, Stroke P. Characteristics of delayed admission to stroke unit. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2006;28(3 4):405–11. doi: 10.1080/10641960600549892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ferro JM, Lopes MG, Rosas MJ, Fontes J. Delay in hospital admission of patients with cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19(3):152–6. doi: 10.1159/000083248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gilligan AK, Thrift AG, Sturm JW, Dewey HM, Macdonell RAL, Donnan GA. Stroke units, tissue plasminogen activator, aspirin and neuroprotection: Which stroke intervention could provide the greatest community benefit? Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;20(4):239–44. doi: 10.1159/000087705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.John M, Palmer P, Faile E, Broce M. Factors causing patients to delay seeking treatment after suffering a stroke. W V Med J. 2005;101(1):12–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Li C-S, Chang K-C, Tan T-Y. The role of emergency medical services in stroke: A hospital-based study in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2005;14(3):126–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tan T-Y, Chang K-C, Liou C-W. Factors delaying hospital arrival after acute stroke in Southern Taiwan. Chang Gung Med J. 2002;25(7):458–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mandelzweig L, Goldbourt U, Boyko V, Tanne D. Perceptual, social, and behavioral factors associated with delays in seeking medical care in patients with symptoms of acute stroke. Stroke. 2006;37(5):1248–53. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217200.61167.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nolte CH, Rossnagel K, Jungehuelsing GJ, et al. Gender differences in knowledge of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Prev Med. 2005;41(1):226–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Qureshi AI, Kirmani JF, Sayed MA, et al. Time to hospital arrival, use of thrombolytics, and in-hospital outcomes in ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2005;64(12):2115–20. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000165951.03373.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Katzan IL, Hammer MD, Hixson ED, Furlan AJ, Abou-Chebl A, Nadzam DM. Utilization of intravenous tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(3):346–50. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Maze LM, Bakas T. Factors associated with hospital arrival time for stroke patients. J Neurosci Nurs. 2004;36(3):136–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bohannon RW, Silverman IE, Ahlquist M. Time to emergency department arrival and its determinants in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Conn Med. 2003;67(3):145–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Harbison J, Hossain O, Jenkinson D, Davis J, Louw SJ, Ford GA. Diagnostic accuracy of stroke referrals from primary care, emergency room physicians, and ambulance staff using the face arm speech test. Stroke. 2003;34(1):71–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000044170.46643.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nedeltchev K, Arnold M, Brekenfeld C, et al. Pre- and in-hospital delays from stroke onset to intra-arterial thrombolysis. Stroke. 2003;34:1230–4. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000069164.91268.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pittock SJ, Meldrum D, Hardiman O, et al. Patient and hospital delays in acute ischaemic stroke in a Dublin teaching hospital. Ir Med J. 2003;96(6):167–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Silliman SL, Quinn B, Huggett V, Merino JG. Use of a field-to-stroke center helicopter transport program to extend thrombolytic therapy to rural residents. Stroke. 2003;34(3):729–33. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000056529.29515.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wojner AW, Morgenstern LB, Alexandrov AV, Rodriguez D, Persse D, Grotta JC. Paramedic and emergency department care of stroke: baseline data from a citywide performance improvement study. Am J Crit Care. 2003;12(5):411–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Derex L, Adeleine P, Nighoghossian N, Honnorat J, Trouillas P. Factors influencing early admission in a French stroke unit. Stroke. 2002;33:153–9. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.100533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Barber PA, Zhang J, Demchuk AM, Hill MD, Buchan AM. Why are stroke patients excluded from TPA therapy? An analysis of patient eligibility. Neurology. 2001;56(8):1015–20. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.8.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cheung R. Hong Kong patients' knowledge of stroke does not influence time-to-hospital presentation. J Clin Neurosci. 2001;8(4):311–4. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2000.0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Goldstein LB, Edwards MG, Wood DP. Delay between stroke onset and emergency department evaluation. Neuroepidemiol. 2001;20(3):196–200. doi: 10.1159/000054787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Johnston SC, Fung LH, Gillum LA, et al. Utilization of intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator for ischemic stroke at academic medical centers: The influence of ethnicity. Stroke. 2001;32(5):1061–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lacy CR, Suh D-C, Bueno M, Kostis JB. Delay in presentation and evaluation for acute stroke : Stroke Time Registry for Outcomes Knowledge and Epidemiology (S.T.R.O.K.E.) Stroke. 2001;32(1):63–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Villa A, Bacchetta A, O E. Time as responsible of ineligibility for thrombolytic treatment in stroke patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18(3):745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Villa A, Bonacina M, Paese S, Omboni E. Letter to the Editor. JAMA. 1999;281(1):32–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yip P, Jeng J, Lu C. Hospital arrival time after onset of different types of stroke in greater Taipei. J Formos Med Assoc. 2000;99(7):532–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Harper G, Haigh R, Potter J, Castleden C. Factors delaying hospital admission after stroke in Leicestershire. Stroke. 1992;23(6):835–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Herderschee D, Limburg M, Hijdra A, Bollen A, Pluvier J, te Water W. Timing of hospital admission in a prospective series of stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1991;1:165–7. [Google Scholar]