Abstract

Background

Genetic association study is currently the primary vehicle for identification and characterization of disease-predisposing variant(s) which usually involves multiple single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) available. However, SNP-wise association tests raise concerns over multiple testing. Haplotype-based methods have the advantage of being able to account for correlations between neighbouring SNPs, yet assuming Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and potentially large number degrees of freedom can harm its statistical power and robustness. Approaches based on principal component analysis (PCA) are preferable in this regard but their performance varies with methods of extracting principal components (PCs).

Results

PCA-based bootstrap confidence interval test (PCA-BCIT), which directly uses the PC scores to assess gene-disease association, was developed and evaluated for three ways of extracting PCs, i.e., cases only(CAES), controls only(COES) and cases and controls combined(CES). Extraction of PCs with COES is preferred to that with CAES and CES. Performance of the test was examined via simulations as well as analyses on data of rheumatoid arthritis and heroin addiction, which maintains nominal level under null hypothesis and showed comparable performance with permutation test.

Conclusions

PCA-BCIT is a valid and powerful method for assessing gene-disease association involving multiple SNPs.

Background

Genetic association studies now customarily involve multiple SNPs in candidate genes or genomic regions and have a significant role in identifying and characterizing disease-predisposing variant(s). A critical challenge in their statistical analysis is how to make optimal use of all available information. Population-based case-control studies have been very popular[1] and typically involve contingency table tests of SNP-disease association[2]. Notably, the genotype-wise Armitage trend test does not require HWE and has equivalent power to its allele-wise counterpart under HWE[3,4]. A thorny issue with individual tests of SNPs for linkage disequilibrium (LD) in such setting is multiple testing, however, methods for multiple testing adjustment assuming independence such as Bonferroni's[5,6] is knowingly conservative[7]. It is therefore necessary to seek alternative approaches which can utilize multiple SNPs simultaneously. The genotype-wise Armitage trend test is appealing since it is equivalent to the score test from logistic regression[8] of case-control status on dosage of disease-predisposing alleles of SNP. However, testing for the effects of multiple SNPs simultaneously via logistic regression is no cure for difficulty with multicollinearity and curse of dimensionality[9]. Haplotype-based methods have many desirable properties[10] and could possibly alleviate the problem[11-14], but assumption of HWE is usually required and a potentially large number of degrees of freedom are involved[7,11,15-18].

It has recently been proposed that PCA can be combined with logistic regression test (LRT)[7,16,17] in a unified framework so that PCA is conducted first to account for between-SNP correlations in a candidate region, then LRT is applied as a formal test for the association between PC scores (linear combinations of the original SNPs) and disease. Since PCs are orthogonal, it avoids multicollinearity and at the meantime is less computer-intensive than haplotype-based methods. Studies have shown that PCA-LRT is at least as powerful as genotype- and haplotype-based methods[7,16,17]. Nevertheless, the power of PCA-based approaches vary with ways by which PCs are extracted, e.g., from genotype correlation, LD, or other kinds of metrics[17], and in principle can be employed in frameworks other than logistic regression[7,16,17]. Here we investigate ways of extracting PCs using genotype correlation matrix from different types of samples in a case-control study, while presenting a new approach testing for gene-disease association by direct use of PC scores in a PCA-based bootstrap confidence interval test (PCA-BCIT). We evaluated its performance via simulations and compared it with PCA-LRT and permutation test using real data.

Methods

PCA

Assume that p SNPs in a candidate region of interest have coded values (X1, X2, ⋯, Xp) according to a given genetic model (e.g., additive model) whose correlation matrix is C. PCA solves the following equation,

| (1) |

where  = 1, i = 1,2, ⋯, p, li = (li1, li2, ⋯, lip)' are loadings of PCs. The score for an individual subject is

= 1, i = 1,2, ⋯, p, li = (li1, li2, ⋯, lip)' are loadings of PCs. The score for an individual subject is

| (2) |

where cov (Fi, Fj) = 0, i ≠ j, and var(F1) ≥ var(F2) ≥ ⋯ ≥ var(Fp).

Methods of extracting PCs

Potentially, PCA can be conducted via four distinct extracting strategies (ES) using case-control data, i.e., 0. Calculate PC scores of individuals in cases and controls separately (SES), 1. Use cases only (CAES) to obtain loadings for calculation of PC scores for subjects in both cases and controls, 2. Use controls only (COES) to obtain the loadings for both groups, and 3. Use combined cases and controls (CES) to obtain the loadings for both groups. It is likely that in a case-control association study, loadings calculated from cases and controls can have different connotations and hence we only consider scenarios 1-3 hereafter. More formally, let (X1, X2, ⋯, Xp) and (Y1, Y2, ⋯, Yp) be p-dimension vectors of SNPs at a given candidate region for cases and controls respectively, then we have,

Strategy 1 (CAES):

| (3) |

where CXX is the correlation matrix of (X1, X2, ⋯, Xp),  and

and  = 1, i = 1,2, ⋯, p. The ith PC for cases is calculated by

= 1, i = 1,2, ⋯, p. The ith PC for cases is calculated by

| (4) |

and for controls

| (5) |

Strategy 2 (COES):

| (6) |

where CYY is the correlation matrix of (Y1, Y2, ⋯, Yp). The ith PC for controls is calculated by

| (7) |

And for cases, the ith PC, i = 1,2, ⋯, p, is calculated by

| (8) |

Strategy 3 (CES):

| (9) |

where C is the correlation matrix obtained from the pooled data of cases and controls,  and

and  . The ith PC of cases is calculated by

. The ith PC of cases is calculated by

| (10) |

The ith PC of controls is calculated by

| (11) |

PCA-BCIT

Given a sample of N cases and M controls with p-SNP genotypes (X1, X2, ⋯, XN)T, (Y1, Y2, ⋯, YM)T, and Xi = (X1i, X2i, ⋯, xpi) for the ith case, Yi = (Y1i, Y2i, ⋯, ypi) for the ith control, a PCA-BCIT is furnished in three steps:

Step 1: Sampling

Replicate samples of cases and controls are obtained with replacement separately from (X1(b, X2(b), ⋯, XN(b))T and (Y1(b, Y2(b), ⋯, YM(b))T, b = 1,2, ⋯, B (B = 1000).

Step 2: PCA

For each replicate sample obtained at Step 1, PCA is conducted and a given number of PCs retained with a threshold of 80% explained variance for all three strategies[16], expressed as  and

and  .

.

Step 3: PCA-BCIT

3a) For each replicate, the mean of the kth PC in cases is calculated by

|

(12) |

and that of the kth PC in controls is calculated by

|

(13) |

3b) Given confidence level (1 - α ), the confidence interval of  is estimated by percentile method, with form

is estimated by percentile method, with form

| (14) |

where  is the

is the  percentile of

percentile of  , and

, and  is the

is the  percentile.

percentile.

The confidence interval of  is estimated by

is estimated by

| (15) |

where  is the

is the  percentile of

percentile of  , and

, and  is the

is the  percentile.

percentile.

3c) Confidence intervals of cases and controls are compared. The null hypothesis is rejected if  and

and  do not overlap, which is

do not overlap, which is  and

and  are statistically different[19], indicating the candidate region is significantly associated with disease at level α. Otherwise, the candidate region is not significantly associated with disease at level α.

are statistically different[19], indicating the candidate region is significantly associated with disease at level α. Otherwise, the candidate region is not significantly associated with disease at level α.

Simulation studies

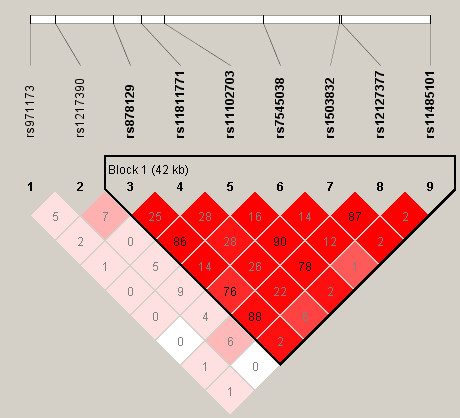

We examine the performance of PCA-BCIT through simulations with data from the North American Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Consortium (NARAC) (868 cases and 1194 controls)[20], taking advantage of the fact that association between protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 22 (PTPN22) and the development of RA has been established[21-24]. Nine SNPs have been selected from the PNPT22 region (114157960-114215857), and most of the SNPs are within the same LD block (Figure 1). Females are more predisposed (73.85%) and are used in our simulation to ensure homogeneity. The corresponding steps for the simulation are as follows.

Figure 1.

LD (r2) among nine PTPN22 SNPs. The nine PTPN22 SNPs are rs971173, rs1217390, rs878129, rs11811771, rs11102703, rs7545038, rs1503832, rs12127377, rs11485101. The triangle marks a single LD block within this region: (rs878129, rs11811771, rs11102703, rs7545038, rs1503832, rs12127377, rs11485101).

Step 1: Sampling

The observed genotype frequencies in the study sample are taken to be their true frequencies in populations of infinite sizes. Replicate samples of cases and controls of given size (N, N = 100, 200, ⋯, 1000) are generated whose estimated genotype frequencies are expected to be close to the true population frequencies while both the allele frequencies and LD structure are maintained. Under null hypothesis, replicate cases and controls are sampled with replacement from the controls. Under alternative hypothesis, replicate cases and controls are sampled with replacement from the cases and controls respectively.

Step 2: PCA-BCITing

For each replicate sample, PCA-BCITs are conducted through the three strategies of extracting PCs as outlined above on association between PC scores and disease (RA).

Step 3: Evaluating performance of PCA-BCITs

Repeat steps 1 and 2 for K ( K = 1000 ) times under both null and alternative hypotheses, and obtain the frequencies (Pα) of rejecting null hypothesis at level α (α = 0.05).

Applications

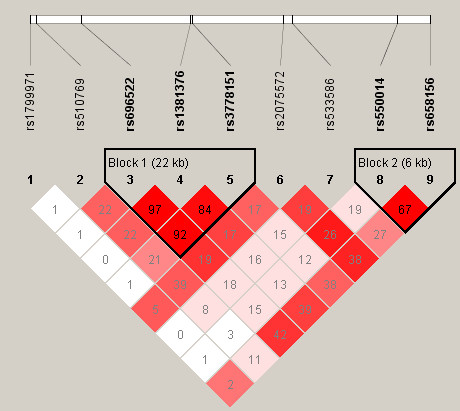

PCA-BCITs are applied to both the NARAC data on PTPN22 in 1493 females (641 cases and 852 controls) described above and a data containing nine SNPs near μ-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) in Han Chinese from Shanghai (91 cases and 245 controls) with endophenotype of heroin-induced positive responses on first use[25]. There are two LD blocks in the region of gene OPRM1 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

LD (r2) among nine OPRM1 SNPs. The nine OPRM1 SNPs are rs1799971, rs510769, rs696522, rs1381376, rs3778151, rs2075572, rs533586, rs550014, rs658156. The triangles mark the LD block 1 (rs696522, rs1381376, rs3778151) and LD block 2 (rs550014, rs658156).

Results

Simulation study

The performance of PCA-BCIT is shown in Table 1 for the three strategies given a range of sample sizes. It can be seen that strategies 2 and 3 both have type I error rates approaching the nominal level (α = 0.05), but those from strategy 1 deviate heavily. When sample size larger than 800, the power of PCA-BCIT is above 0.8, and strategies 2 and 3 outperform strategy 1 slightly.

Table 1.

Performance of PCA-BCIT at level 0.05 with strategies 1-3†

| Sample size | Type I error | Power | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 100 | 0.014 | 0.036 | 0.037 | 0.156 | 0.163 | 0.176 |

| 200 | 0.016 | 0.044 | 0.036 | 0.249 | 0.278 | 0.292 |

| 300 | 0.017 | 0.028 | 0.029 | 0.383 | 0.426 | 0.368 |

| 400 | 0.014 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.508 | 0.485 | 0.516 |

| 500 | 0.009 | 0.035 | 0.042 | 0.613 | 0.595 | 0.597 |

| 600 | 0.006 | 0.032 | 0.042 | 0.677 | 0.662 | 0.683 |

| 700 | 0.007 | 0.061 | 0.04 | 0.733 | 0.758 | 0.73 |

| 800 | 0.004 | 0.043 | 0.045 | 0.801 | 0.791 | 0.819 |

| 900 | 0.005 | 0.057 | 0.051 | 0.826 | 0.855 | 0.858 |

| 1000 | 0.01 | 0.056 | 0.05 | 0.871 | 0.901 | 0.889 |

†1 case-only extracting strategy (CAES), 2 control-only extracting strategy (COES), 3 case-control extracting strategy (CES)

Applications

For the NARAC data, Armitage trend test reveals none of the SNPs in significant association with RA using Bonferroni correction (Table 2), but the results of PCA-BCIT with strategies 2 and 3 show that the first PC extracted in region of PTPN22 is significantly associated with RA. The results are similar to that from permutation test (Table 3).

Table 2.

Armitage trend test on nine PTPN22 SNPs and RA susceptibility

| SNP | Genotype | Female | Male | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | P-value | Case | control | P-value | ||

| rs971173 | CC | 334 | 381 | 0.025 | 116 | 169 | 0.779 |

| AC | 236 | 363 | 85 | 134 | |||

| AA | 71 | 106 | 26 | 39 | |||

| rs1217390 | AA | 268 | 319 | 0.333 | 99 | 112 | 0.108 |

| AG | 272 | 392 | 89 | 175 | |||

| GG | 98 | 138 | 38 | 55 | |||

| rs878129 | GG | 338 | 507 | 0.009 | 131 | 187 | 0.384 |

| AG | 251 | 291 | 83 | 130 | |||

| AA | 52 | 54 | 13 | 25 | |||

| rs11811771 | AA | 224 | 272 | 0.090 | 78 | 111 | 0.717 |

| AG | 303 | 411 | 104 | 168 | |||

| GG | 112 | 169 | 45 | 62 | |||

| rs11102703 | CC | 312 | 469 | 0.024 | 121 | 174 | 0.418 |

| AC | 269 | 314 | 90 | 137 | |||

| AA | 60 | 69 | 16 | 31 | |||

| rs7545038 | GG | 321 | 428 | 0.696 | 109 | 186 | 0.417 |

| AG | 265 | 342 | 98 | 114 | |||

| AA | 52 | 80 | 20 | 40 | |||

| rs1503832 | AA | 324 | 487 | 0.013 | 129 | 185 | 0.249 |

| AG | 262 | 306 | 86 | 127 | |||

| GG | 55 | 59 | 12 | 30 | |||

| rs12127377 | AA | 349 | 521 | 0.017 | 139 | 197 | 0.230 |

| AG | 243 | 282 | 78 | 121 | |||

| GG | 49 | 48 | 10 | 24 | |||

| rs11485101 | AA | 564 | 738 | 0.656 | 206 | 305 | 0.430 |

| AG | 72 | 112 | 21 | 35 | |||

| GG | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

None of the P-values is significant after Bonferroni Correction.

Table 3.

PCA-BCIT, PCA-LRT and permutation test on real data

| Study | Strategy† | 99%CI | 95%CI | P-value‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA-LRT | Permutation test | ||||

| PTPN22 | 2 | (-5.4E-01,-4.7E-03)** (-7.5E-16,6.9E-16) |

(-4.8E-01,-8.6E-02)* (-4.6E-16,4.2E-16) |

0.006** | 0.002** |

| 3 | (1.7E-02,3.3E-01)** (-2.5E-01,-1.3E-02) |

(4.9E-02,3.0E-01)* (-2.2E-01,-3.7E-02) |

0.007** | 0.002** | |

| OPRM1 | 2 | (-1.2E+00,-1.1E-02)** (-4.7E-16,5.0E-16) |

(-1.1E+00,-1.8E-01)* (-3.7E-16,3.4E-16) |

0.107 | 0.002** |

| 3 | (5.3E-02,1.4E+00)** (-4.9E-01,-1.7E-02) |

(2.4E-01,1.2E+00)* (-4.2E-01,-8.0E-02) |

0.012* | 0.004** | |

†2 control-only extracting strategy (COES), 3 case-control extracting strategy (CES)

‡* significant at levels α = 0.05(*) and α = 0.01 (**).

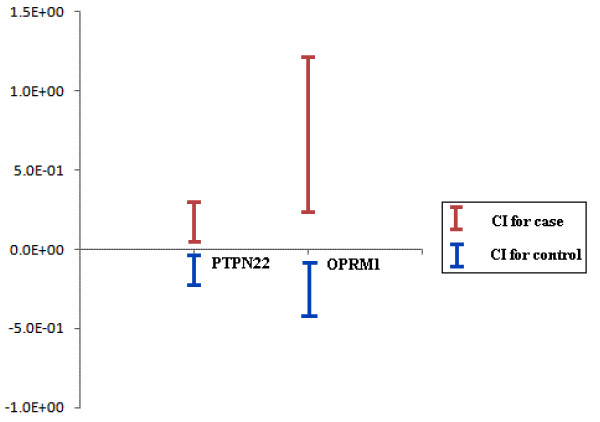

For the OPRM1 data, the sample characteristics are comparable between cases and controls (Table 4), and three SNPs (rs696522, rs1381376 and rs3778151) are showed significant association with the endophenotype (Table 5). The results of PCA-BCIT with strategies 2 and 3 and permutation test are all significant at level α = 0.01. In contrast, result from PCA-LRT is not significant at level α = 0.05 with strategy 2 (Table 3). The apparent separation of cases and controls are shown in Figure 3 for PCA-BCIT with strategy 3, suggesting an intuitive interpretation.

Table 4.

Sample characteristics of heroin-induced positive responses on first use

| Cases (N = 91) | Controls (N = 245) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 30.42 ± 7.65 | 30.93 ± 8.18 | 0.6057 |

| Women (%) | 26.4 | 29.8 | 0.5384 |

| Age at onset (yrs) | 26.29 ± 7.41 | 26.97 ± 7.89 | 0.4760 |

| Reason for first use of heroin | 0.7173 | ||

| Curiousness | 79.1 | 75.1 | |

| Peer pressure | 6.6 | 4.9 | |

| Physical disease | 7.7 | 10.2 | |

| Trouble | 5.5 | 6.1 | |

| Other reasons | 1.1 | 3.8 |

Table 5.

Armitage trend tests on nine OPRM1 SNPs and heroin-induced positive responses on first use

| SNP | Genotype | Count and frequency | Armitage trend test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Chi-square | P-value | ||||

| rs1799971 | AA | 55 | 0.604 | 150 | 0.622 | 0.003 | 0.9537 |

| AG | 27 | 0.297 | 64 | 0.266 | |||

| GG | 9 | 0.099 | 24 | 0.112 | |||

| rs510769 | TT | 56 | 0.667 | 167 | 0.749 | 2.744 | 0.0976 |

| TC | 24 | 0.286 | 53 | 0.237 | |||

| CC | 4 | 0.048 | 4 | 0.018 | |||

| rs696522 | AA | 64 | 0.762 | 215 | 0.907 | 11.097 | 0.0009* |

| AG | 19 | 0.226 | 21 | 0.089 | |||

| GG | 1 | 0.012 | 1 | 0.004 | |||

| rs1381376 | CC | 70 | 0.769 | 221 | 0.913 | 13.409 | 0.0003* |

| CT | 20 | 0.220 | 21 | 0.087 | |||

| TT | 1 | 0.011 | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| rs3778151 | GG | 66 | 0.733 | 215 | 0.896 | 14.655 | 0.0001* |

| GA | 23 | 0.256 | 25 | 0.104 | |||

| AA | 1 | 0.011 | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| rs2075572 | GG | 50 | 0.556 | 149 | 0.642 | 1.574 | 0.2096 |

| GC | 33 | 0.367 | 82 | 0.353 | |||

| CC | 7 | 0.078 | 11 | 0.047 | |||

| rs533586 | TT | 68 | 0.840 | 203 | 0.868 | 0.761 | 0.3830 |

| TC | 12 | 0.148 | 31 | 0.132 | |||

| CC | 1 | 0.012 | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| rs550014 | TT | 78 | 0.857 | 203 | 0.832 | 0.093 | 0.7602 |

| TC | 12 | 0.132 | 41 | 0.168 | |||

| CC | 1 | 0.011 | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| rs658156 | GG | 65 | 0.714 | 192 | 0.787 | 2.041 | 0.1531 |

| GA | 24 | 0.264 | 52 | 0.213 | |||

| AA | 1 | 0.011 | 0 | 0.000 | |||

* significant after Bonferroni Correction.

Figure 3.

Real data analyses by PCA-BCIT with strategy 3 and confidence level 0.95. The horizontal axis denotes studies and vertical axis mean(PC1), the statistic used to calculate confidence intervals for cases and controls. PCA-BCITs with strategy 3 were significant at confidence level 0.95.

Discussion

In this study, a PCA-based bootstrap confidence interval test[19,26-28] (PCA-BCIT) is developed to study gene-disease association using all SNPs genotyped in a given region. There are several attractive features of PCA-based approaches. First of all, they are at least as powerful as genotype- and haplotype-based methods[7,16,17]. Secondly, they are able to capture LD information between correlated SNPs and easy to compute with needless consideration of multicollinearity and multiple testing. Thirdly, BCIT integrates point estimation and hypothesis testing as a single inferential statement of great intuitive appeal[29] and does not rely on the distributional assumption of the statistic used to calculate confidence interval[19,26-29].

While there have been several different but closely related forms of bootstrap confidence interval calculations[28], we focus on percentiles of the asymptotic distribution of PCs for given confidence levels to estimate the confidence interval. PCA-BCIT is a data-learning method[29], and shown to be valid and powerful for sufficiently large number of replicates in our study. Our investigation involving three strategies of extracting PCs reveals that strategy 1 is invalid, while strategies 2 and 3 are acceptable. From analyses of real data we find that PCA-BCIT is more favourable compared with PCA-LRT and permutation test. It is suggested that a practical advantage of PCA-BCIT is that it offers an intuitive measure of difference between cases and controls by using the set of SNPs (PC scores) in a candidate region (Figure 3). As extraction of PCs through COES is more in line with the principle of a case-control study, it will be our method of choice given that it has a comparable performance with CES. Nevertheless, PCA-BCIT has the limitation that it does not directly handle covariates as is usually done in a regression model.

Conclusions

PCA-BCIT is both a valid and a powerful PCA-based method which captures multi-SNP information in study of gene-disease association. While extracting PCs based on CAES, COES and CES all have good performances, it appears that COES is more appropriate to use.

Abbreviations

SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism; HWE: Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium; LD: linkage disequilibrium; LRT: logistic regression test; PCA: principle component analysis; PC: principle component; ES: extracting strategy; SES: separate case and control extracting strategy (strategy 0); CAES: case-based extracting strategy (strategy 1); COES: control-based extracting strategy (strategy 2); CES: combined case and control extracting strategy (strategy 3); BCIT: bootstrap confidence interval test.

Authors' contributions

QQP, JHZ, and FZX conceptualized the study, acquired and analyzed the data and prepared for the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Qianqian Peng, Email: louise1984@yahoo.cn.

Jinghua Zhao, Email: jinghua.zhao@mrc-epid.cam.ac.uk.

Fuzhong Xue, Email: xuefzh@sdu.edu.cn.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30871392). We wish to thank Dr. Dandan Zhang (Fudan University) and NARAC for supplying us with the data, and comments from the Associate Editor and anonymous referees which greatly improved the manuscript. Special thanks to referee for the insightful comment that extraction of PCs with controls is line with the case-control principles.

References

- Morton NE, Collins A. Tests and estimates of allelic association in comples. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11389–11393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasieni PD. From genotypes to genes: doubling the sample size. Biometrics. 1997;53:1253–1261. doi: 10.2307/2533494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D, Haynes C, Yang Y, Kramer PL, Finch SJ. Linear trend tests for case-control genetic association that incorporate random phenotype and genotype misclassification error. Genet Epidemiol. 2007;31:853–870. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slager SL, Schaid DJ. Case-control studies of genetic markers: Power and sample size approximations for Armitage's test for trend. Human Heredity. 2001;52:149–153. doi: 10.1159/000053370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidak Z. On Multivariate Normal Probabilities of Rectangles: Their Dependence on Correlations. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1968;39:1425–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Sidak Z. On Probabilities of Rectangles in Multivariate Student Distributions: Their Dependence on Correlations. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1971;42:169–175. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177693504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang FY, Wagener D. An approach to incorporate linkage disequilibrium structure into genomic association analysis. Journal of Genetics and Genomics. 2008;35:381–385. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60055-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balding DJ. A tutorial on statistical methods for population association studies. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2006;7:781–791. doi: 10.1038/nrg1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaid DJ, McDonnell SK, Hebbring SJ, Cunningham JM, Thibodeau SN. Nonparametric tests of association of multiple genes with human disease. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;76:780–793. doi: 10.1086/429838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker T, Schumacher J, Cichon S, Baur MP, Knapp M. Haplotype interaction analysis of unlinked regions. Genetic Epidemiology. 2005;29:313–322. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JM, Cooper JD, Todd JA, Clayton DG. Detecting disease associations due to linkage disequilibrium using haplotype tags: A class of tests and the determinants of statistical power. Human Heredity. 2003;56:18–31. doi: 10.1159/000073729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein MP, Satten GA. Inference on haplotype effects in case-control studies using unphased genotype data. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;73:1316–1329. doi: 10.1086/380204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallin D, Cohen A, Essioux L, Chumakov I, Blumenfeld M, Cohen D, Schork NJ. Genetic analysis of case/control data using estimated haplotype frequencies: Application to APOE locus variation and Alzheimer's disease. Genome Research. 2001;11:143–151. doi: 10.1101/gr.148401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stram DO, Pearce CL, Bretsky P, Freedman M, Hirschhorn JN, Altshuler D, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Thomas DC. Modeling and E-M estimation of haplotype-specific relative risks from genotype data for a case-control study of unrelated individuals. Human Heredity. 2003;55:179–190. doi: 10.1159/000073202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton D, Chapman J, Cooper J. Use of unphased multilocus genotype data in indirect association studies. Genetic Epidemiology. 2004;27:415–428. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauderman WJ, Murcray C, Gilliland F, Conti DV. Testing association between disease and multiple SNPs in a candidate gene. Genetic Epidemiology. 2007;31:383–395. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S, Park T. Association tests based on the principal-component analysis. BMC Proc. 2007;1(Suppl 1):S130. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-1-s1-s130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Elston RC. Improved power by use of a weighted score test for linkage disequilibrium mapping. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;80:353–360. doi: 10.1086/511312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller G, Venkatraman ES. Resampling procedures to compare two survival distributions in the presence of right-censored data. Biometrics. 1996;52:1204–1213. doi: 10.2307/2532836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plenge RM, Seielstad M, Padyukov L, Lee AT, Remmers EF, Ding B, Liew A, Khalili H, Chandrasekaran A, Davies LRL. TRAF1-C5 as a risk locus for rheumatoid arthritis - A genomewide study. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begovich AB, Carlton VE, Honigberg LA, Schrodi SJ, Chokkalingam AP, Alexander HC, Ardlie KG, Huang Q, Smith AM, Spoerke JM. A missense single-nucleotide polymorphism in a gene encoding a protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPN22) is associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:330–337. doi: 10.1086/422827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton VEH, Hu XL, Chokkalingam AP, Schrodi SJ, Brandon R, Alexander HC, Chang M, Catanese JJ, Leong DU, Ardlie KG. PTPN22 genetic variation: Evidence for multiple variants associated with rheumatoid arthritis. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;77:567–581. doi: 10.1086/468189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallberg H, Padyukov L, Plenge RM, Ronnelid J, Gregersen PK, Helm-van Mil AHM van der, Toes REM, Huizinga TW, Klareskog L, Alfredsson L. Gene-gene and gene-environment interactions involving HLA-DRB1, PTPN22, and smoking in two subsets of rheumatoid arthritis. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;80:867–875. doi: 10.1086/516736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plenge RM, Padyukov L, Remmers EF, Purcell S, Lee AT, Karlson EW, Wolfe F, Kastner DL, Alfredsson L, Altshuler D. Replication of putative candidate-gene associations with rheumatoid arthritis in > 4,000 samples from North America and Sweden: Association of susceptibility with PTPN22, CTLA4, and PADI4. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;77:1044–1060. doi: 10.1086/498651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Shao C, Shao M, Yan P, Wang Y, Liu Y, Liu W, Lin T, Xie Y, Zhao Y. Effect of mu-opioid receptor gene polymorphisms on heroin-induced subjective responses in a Chinese population. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:1244–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter J. Test Inversion Bootstrap Confidence Intervals. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Statistical Methodology) 1999;61:159–172. doi: 10.1111/1467-9868.00169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davison AC, Hinkley DV, Young GA. Recent developments in bootstrap methodology. Statistical Science. 2003;18:141–157. doi: 10.1214/ss/1063994969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DiCiccio TJ, Efron B. Bootstrap confidence intervals. Statistical Science. 1996;11:189–212. doi: 10.1214/ss/1032280214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Bootstrap Methods: Another Look at the Jackknife. The Annals of Statistics. 1979;7:1–26. doi: 10.1214/aos/1176344552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]