Abstract

Sialic acids are a subset of nonulosonic acids, which are nine-carbon alpha-keto aldonic acids. Natural existing sialic acid-containing structures are presented in different sialic acid forms, various sialyl linkages, and on diverse underlying glycans. They play important roles in biological, pathological, and immunological processes. Sialobiology has been a challenging and yet attractive research area. Recent advances in chemical and chemoenzymatic synthesis as well as large-scale E. coli cell-based production have provided a large library of sialoside standards and derivatives in amounts sufficient for structure-activity relationship studies. Sialoglycan microarrays provide an efficient platform for quick identification of preferred ligands for sialic acid-binding proteins. Future research on sialic acid will continue to be at the interface of chemistry and biology. Research efforts will not only lead to a better understanding of the biological and pathological importance of sialic acids and their diversity, but could also lead to the development of therapeutics.

Keywords: biology, carbohydrate, chemistry, CMP-sialic acid synthetase, glycan, sialic acid, sialic acid aldolase, sialidase, sialoside, sialyltransferase

Diversity of Sialic Acids in Nature

Sialic acids are a Subset of Nonulosonic Acids

Not long ago, it was thought that sialic acids (Sias) were unique inventions of the deuterostome lineage of animals, which emerged around the time of the Cambrian expansion ~530 million years ago, with certain pathogenic bacteria having then “acquired” them from hosts by gene transfer (1–2). However, the relevant genes of bacterial pathogens were then found to be only distantly homologous to corresponding host genes (3). Meanwhile, work from multiple investigators over the last few decades has shown that the unusual 9-carbon backbone of Sias is in fact shared by a larger family of nonulosonic acids (NulOs), which are much more widely distributed in nature (4–6). Furthermore, the key steps in the biosynthesis of nonulosonic acids share remarkable similarities, and the genes involved are homologous. These aspects have recently been discussed extensively in a phylogenomic evaluation of nonulosonic acids (7). Although the other forms of nonulosonic acids, such as legionaminic acid and pseudaminic acid, have sometimes been called “bacterial sialic acids” (4), we prefer to reserve the term Sia for the 9-carbon sugars found both in the deuterostome lineage of animals and in certain bacteria that are based on a neuraminic acid (Neu) or a 2-keto-3-deoxy-nonulosonic acid (Kdn) backbone (7) (Figure 1). Thus, this review will focus only on these “traditional” Sias, emphasizing recent challenges and advances at the interface of chemistry and biology.

Figure 1.

Naturally existing sialic acids (a–c) and some other common nonulosonic acids (d and e). Many possible modifications and sialosidic linkage varieties found in nature are not shown here (see references 1–7).

Natural Structural Diversity in Sialic Acids

Even within this restricted subset of nonulosonic acids of the deuterostome lineage, there is a remarkable array of natural modifications, exceeding that of any other common monosaccharide (1, 3, 8). The reasons for this chemical diversity are not entirely clear, but a reasonable hypothesis is that they represent the outcome of ongoing evolutionary selection by host-pathogen interactions, in the face of selection to conserve critical endogenous functions (3, 9). Regardless of the reasons, this diversity poses many interesting questions, opportunities, and challenges. Most of the diversity arises from modifications at C-5, e.g. the N-glycolyl group; or, at the C-4, C-7, C-8, and C-9 hydroxyl groups, e.g., O-acetyl esters. The reader is referred to reviews that discuss and list these and other modifications such as O-methyl groups, sulfate esters, and lactyl esters (1–3). Most research to date has focused on N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) and to a lesser extent on its O-acetylated derivatives, with recent increasing interest in N-glycolylneuramic acid, because its synthesis was selectively abolished during human evolution (8, 10, 11).

Natural Diversity in Sialic Acid Linkages and Underlying Glycans

Beyond variations within the Sia molecule, additional diversity arises from a variety of glycosidic linkages from C-2 to the underlying glycans. Again, details have been discussed elsewhere (1–3, 8, 12), regarding families of sialyltransferases that synthesize the different linkages. Further complexity arises from the fact that these linkages can be presented on different underlying glycan chains, variations that can further alter the biology of Sias. Combinations of all these possibilities generate a wide variety of presentations of Sias in nature, and we are only beginning to scratch the surface of this diversity from the chemical, synthetic, and biological point of view. A further level of complexity arises because sialoglycans on cell surfaces can be organized into “clustered saccharide patches” which involve interactions with other glycans, modulating recognition by different Sia-recognizing proteins (13).

Evolutionary Patterns of Sialic Acid Diversity

For sialic acids in deuterostome animals, it was once thought that each type of Sia was unique to different lineages of deuterostome animals. This is actually not the case, and most of these kinds of Sias are probably present in most vertebrates. However, there are marked cell-type and species-specific differences in the levels of modifications found in nature, as well as instances of complete elimination of some kinds of Sias from the entire lineage. An example is the complete loss of biosynthesis of N-glycolylneuraminic acid in humans (8, 10, 11) and very likely as an independent event in sauropods (birds and reptiles) (14).

Sialic Acids as Key Components of Bacterial Polysaccharides

Multiple bacterial polysaccharides and lipooligosaccharides are known to contain Sias either as terminal structures, or in the form of polysialic acid. In several cases they can be also modified, particularly with O-acetyl groups (5, 15). Interestingly many of these Sia-producing bacteria seem to have independently invented Sias by convergent evolution in order to dampen immune responses in vertebrates, and the biosynthetic pathways involved are related to those that can synthesize the more distantly related nonulosonic acids (7). In addition to the well known effects of microbial Sias in negative charge repulsion, inhibiting alternate complement pathway activation by factor H recognition (16) and masking of underlying antigenic residues, it has recently emerged that the Sias on these pathogens “take advantage” of inhibitory Siglecs present on innate immune cells. Thus by engaging these Siglecs, the bacteria send a false “self signal” to the innate cells and avoid attack (17).

Of note, the great majority of Sia-producing bacteria that have been reported to date are human-specific pathogens or commensals. One theory to explain this is the fact that no microbe has reinvented the ability to express the sialic acid N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc). This could be because the conversion of an N-acetyl group to and N-glycolyl group is a difficult chemical barrier. Regardless of the reasons, when humans lost Neu5Gc and ended up with an excess of the precursor Neu5Ac, our Siglecs then apparently underwent evolutionary adjustments to recognize this change (10). This may have opened up a niche for bacteria that can express Neu5Ac and take advantage of the Neu5Ac-preferring human Siglecs. In keeping with this, Neu5Ac has been “re-invented” multiple times by various human-specific pathogens.

Sialobiology as a Challenging Area for Analytical and Synthetic Chemistry

Sialic acids have many major biological roles, ranging from embryogenesis to neural plasticity, to pathogen interactions, and these are detailed elsewhere (8, 10, 18). At the present time, the methodologies to study these modifications and their biological roles remain somewhat limited. In comparison to progress in studies of other monosaccharides, much improvement is still needed in analytical approaches to Sias, as well in their synthesis. Many of the difficulties relate to the unusual 9-carbon backbone of Sias, the relative acid lability of its glycosidic linkages, and the instability of some of its modifications. Examples of major difficulties in analysis compared to other monosaccharides include the migration and loss of O-acetyl esters, the difficulty in obtaining stable derivatized molecules for mass spectrometric analyses, and the instability of CMP-sialic acids.

Meanwhile, chemical sialylation has been considered as one of the most challenging glycosylation reactions due to the hindered and disfavored tertiary anomeric center, the presence of an electron-withdrawing carboxyl group linked to the anomeric carbon, the lack of a neighboring participating group in sialic acids to regulate the stereochemistry outcome of the sialosidic linkage in the products (19, 20). In addition, because acetyl group has been a popular protecting group for the hydroxyl groups in carbohydrate synthesis and it is labile under mild basic conditions, chemical production of sialosides with sialic acid O-acetyl modifications or other labile O-acyl groups (e.g. O-lactyl) are not practical.

Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Sialosides: Chemical Synthesis

Many advances have been made for chemical sialylation, which allows access to some interesting sialic acid-containing structures. The reader is referred to two excellent reviews (20, 21) regarding some direct and indirect chemical sialylation approaches and the incorporation of enzymes into sialoside synthetic schemes. In general, introduction of N,N-diacetyl (22, 23), azido (24), N-trifluoroacetyl (N-TFA) (Figure 2a) (25, 26), N-2,2,2-trichloroethoxycarbonyl (N-Troc) (27–29), N-9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (N-Fmoc) (28, 29), N-trichloroacetyl (28, 29), or N-phthalimide group (30) at the C-5 position in sialyl donors showed improved donor reactivity towards sialylation and enhanced stereochemistry outcome of the sialyl products. Some of these N-protecting groups also allowed access to different sialic acid forms (e.g. Neu5Gc) by deprotection of the glycosylated product followed by derivatization at C-5 amino group (20). Recently developed donors include C-4-aminated sialyl hemiketal donor (Figure 2b) (31), 5-N,4-O-carbonyl (32, 33) (Figure 2c) and N-acyl-5-N,4-O-carbonyl (Figure 2d) (34–36) protected sialyl donors. C2-Hemiketal sialyl donors with a C-4 cyclic secondary amine auxiliary (Figure 2b) improved α-stereoselectivity in the formation of sialyl linkages with primary (90–98% yields with α/β ratios varied from 91:9 to 98:2 in comparison to 94–98% yields with α/β ratios varied from 1:2 to 1.5:1 for similar donor with no C-4 auxiliary) and secondary alcohols (90–95% yields with α/β ratios varied from 91:9 to 96:4) (31). The α-selectivities in the formation of 2–6-linked sialyl galactosides or sialyl glucosides was dependent on substrates with α/β ratios varied from 3:2 to a only while yields are quite consistent (89–91%) (31). In addition, N,N-dimethylglycolamide was used as a new C-1-auxiliary in sialyl donors including sialyl chlorides, sulfides, and phosphites (Figure 2e) for chemical sialylation reactions to improve the stereoselective formation of α2–3- and α2–6-sialyl linkages (37). Compared to a sialyl donor with a traditional methyl ester protecting group at C-1, the donor with the N,N-dimethylglycolamide auxiliary at C-1 showed improved α-selectivity for the formation of sialyl linkages (α/β ratios improved from 1:10–5:1 to 2:1–13:1 with similar or improved yields). The C-1 auxiliary neighboring group participation strategy was general and applicable for common sialylation donors including sialyl chlorides, sulfides, and phosphites (37). The strategy was also applicable to optimize dehydrative chemical sialylation conditions when C2-sialyl hemiketals were used as sialyl donors (Figure 2f) (38). Sialyl N-phenyltrifuloroacetimidate donors (Figure 2g) were shown to be effective donors for direct sialylation when catalytic amount of trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate (TMSOTf) was used as a promoter (39). Some of these sialyl donors, including C-5 N-trifluoroacetyl (N-TFA) (Figure 2a) (26) and 5-N,4-O-carbonyl protected (Figure 2c and 2d) (32, 33) sialyl donor as well as the 1,5-lactame derivative of sialic acid (40, 41), were used for the synthesis of more challenging α2–8-linked disialylated oligosaccharides in moderate yields (23, 26, 30). The reactivity of the C-8 hydroxyl of sialic acid acceptors for the synthesis of α2–8-linked disialylated oligosaccharides was also improved using the C-5 N-TFA protecting group (26). Another useful strategy for efficient chemical synthesis of complex sialosides was to use chemically synthesized sialyloligosaccharide building blocks for further glycosylations to produce more complex structures (42, 43). Despite recent advances, current chemical synthesis of sialosides remains to be a time-consuming process and requires skillful expertise.

Figure 2.

Sialyl donors used in recent chemical sialylation reactions.

Large-Scale Synthesis of Sialosides Using Genetically Engineered Microorganisms

The Whole Cell Approach

Large-scale production of Neu5Acα2–3Lac was achieved by researchers in Kyowa Kakko Kogyo Co., Ltd. in Japan (44) using permeablized whole cells of a Corynebacterium ammoniagenes strain [by treating cell pellets with polyoxyethylene octadecylamine (Nymeen S-215) and dimethylbenzenes (xylene)] and three recombinant E. coli strains as catalysts. UTP was produced from inexpensive orotic acid by the C. ammoniagenes DN510 cells which also converted CMP to CDP. The UTP and CDP obtained were used for producing CTP by E. coli NM294 cells with a plasmid containing pyrG gene for E. coli K12 CTP synthetase. The CTP produced reacted with Neu5Ac to form CMP-Neu5Ac catalyzed by E. coli NM522 cells with a plasmid containing neuA gene for E. coli K1 CMP-Neu5Ac synthetase. The CMP-Neu5Ac and lactose were used by E. coli NM522 cells containing a plasmid for Neisseria gonorrhoeae α2–3-sialyltransferase for the formation of 3′-sialyllactose Neu5Acα2–3Lac. The CMP byproduct of the sialyltransferase reaction can be recycled back to CDP by the Corynebacterium ammoniagenes cells. A 36% yield (0.99 g) was obtained from a 30 mL reaction carried out in a 200 mL beaker at 32 °C for 11 h and a 44% yield (72 g) was achieved from a 2 L reaction carried out in a 5 L fermentor at 32 °C for 11 h from lactose, Neu5Ac, and orotic acid.

The Living Factory Approach

Genetically engineering living E. coli cells have been used to produce sialosides in gram scales by the Samain group. The most significant advantage is that nucleotides, simple monosaccharides, and some sugar nucleotides (e.g. UDP-GlcNAc, UDP-Gal, UDP-Glc, GDP-Fuc) (45) are provided by living bacterial cells’ own metabolic machinery from simple carbon and energy source such as glycerol. The method uses a β-galactosidase-negative (lacZ−) E. coli strain JM107, which is genetically engineered to delete the sialic acid aldolase gene nanA and add plasmids containing sialoside biosynthetic genes.

Early attempts achieved the synthesis of 3′-sialyllactose (Neu5Acα2–3Galβ1–4Glc) by feeding engineered (lacZ− and nanA−) living cells transformed with two plasmids containing an N. meningitidis CMP-Neu5Ac synthetase and an N. meningitidis α2–3-sialyltransferase respectively with exogenous Neu5Ac and lactose (46). Neu5Ac was transported into the cells by permease NanT and lactose was incorporated by β-galactoside permease LacY, both enzymes being endogenous to the E. coli host cells. By incorporating plasmids containing additional glycosyltransferase genes into the genetically engineered (lacZ− and nanA−) E. coli K12 strain JM107, the method has been used for the gram-scale synthesis of carbohydrate portions GalNAcβ1–4(Neu5Acα2–3)Galβ1–4Glc and Galβ1–3GalNAcβ1–4(Neu5Acα2–3)Galβ1–4Glc of gangliosides GM2 and GM1, respectively (46). For the synthesis of GM2 oligosaccharide, in addition to a plasmid containing a CMP-Neu5Ac synthetase gene and an α2–3-sialyltransferase gene from N. meninigitidis, a plasmid pACT3cgtA carrying a C. jejuni cgtA gene for a β1–4-GalNAc transferase and a plasmid carrying a P. aeruginosa wbpP gene for UDP-GlcNAc C4-epimerase, respectively, were introduced. GM2 oligosaccharide was produced in both the intracellular fraction and extracellular fraction from lactose and Neu5Ac after 20 h of isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG) induction. Improved efficiency in large-scale synthesis of GM2 oligosaccharide (71%) was achieved by using high cell density cultivation and the increase of the amount of lactose and Neu5Ac. By introducing an additional glycosyltransferase gene C. jejuni cgtB for a β1–3GalT downstream of the cgtA in the plasmid pACT3cgtA in the GM2 biosynthetic cells, the engineered cells were used to produce GM1 oligosaccharide in intracellular fraction and side-products sialyllactose and GM2 in both intracellular and extracellular fractions (47).

The tolerance of β-galactoside permease LacY in transporting lactoside derivatives into E. coli cells was also explored. Lactosides with an allyl or a propargyl aglycon were readily internalized into the cell and GM2 and GM3 ganglioside oligosaccharides were successfully synthesized using the living factory approach. In contrast, N-allyl acetamide β-lactoside was not able to be internalized into the cell and an azido ethyl lactoside gave poor results (48).

To avoid adding exogenous relative expensive Neu5Ac as one of the starting materials, 3′-sialyllactose biosynthetic E. coli K12 cells (45) were engineered further by deleting ManNAc kinase nanK gene and incorporating plasmids containing Campylobacter jejuni neuC and neuB genes encoding N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate-epimerase and sialic acid synthase, respectively, for producing Neu5Ac from endogenous UDP-GlcNAc (49). Using this improved engineered bacterial strain, 3′-sialyllactose was obtained at a much higher concentration (25 g L−1) compared to that obtained previously (2.6 g L−1) (46). In addition, the new system does not require the addition of exogenous Neu5Ac, thus decreasing the cost of production further.

Both whole cell-based approaches discussed above take the advantage of microorganisms’ own metabolic machinery for the synthesis of sialosides from inexpensive materials without adding nucleotides. One of the limitations of the living factory approach for large-scale synthesis of sialosides is that the glycosyltransferase acceptors that can be used are restricted to those can be internalized by the cells. In addition, further improvements will be needed for both whole cell-based approaches to be applicable in obtaining sialosides containing different forms of sialic acid including those contain the labile O-acetyl or O-lactyl groups.

Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

Chemoenzymatic synthesis combines the flexibility of chemical synthesis and the highly efficient stereo- and regio-selective enzymatic approaches. It is considered as one of the most effective ways to generate natural occurring and non-natural sialosides with great diversity. Most chemoenzymatic methods involve chemical or chemoenzymatic synthesis of sialyltransferase acceptors and sialic acid derivatives or precursors followed by enzyme-catalyzed formation of sialoside products. However, an alternative chemoenzymatic method using enzymatically synthesized sialyloligosaccharides as building blocks for chemical synthesis of more complex sialosides has also been explored for the synthesis of sialyl galactosides (50, 51) and sialyl Lewis x tetrasaccharide (52, 53).

Bacterial Sialoside Biosynthetic Enzymes

Recent discovery of many bacterial sialoside biosynthetic enzymes with substrate promiscuity greatly expands the scope of applying enzymatic methods in synthesizing natural occurring and non-natural sialosides. A key finding is that enzymes from different bacterial sources have significant diversity in tolerating substrate modifications even if they catalyze the same reaction or share sequence similarity.

Sialic acids and their derivatives are commonly synthesized from N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc), mannose, or their derivatives as the six-carbon precursors of Neu5Ac, Kdn, or their analogs, respectively. Although bacterial sialic acid synthases are the enzymes responsible for the formation of sialic acids in nature, a reversed reaction catalyzed by sialic acid degrading enzymes (sialic acid aldolases) has been used more commonly in the large-scale synthesis of sialic acids and their derivatives. This is because of the low cost of the pyruvate used by the sialic acid aldolase-catalyzed formation of sialic acids, compared to the phosphoenol pyruvate required by the sialic acid synthase. Other than the most commonly used recombinant E. coli sialic acid aldolase (54), a recently cloned Pasteurella multocida sialic acid aldolase has shown a higher expression level and a more promiscuous substrate tolerance than the E. coli enzyme (55).

Sialic acids and their derivatives can be activated by CMP-sialic acid synthetases (CSSs) to form CMP-sialic acids, the sugar nucleotide donors required by sialyltransferase-catalyzed reactions for the synthesis of sialosides. Among three CMP-sialic acid synthetases cloned from E. coli, Streptococcus agalactiae, and N. meningitidis, the N. meningitidis enzyme (NmCSS) is the best with regard to expression level, activity, and tolerance towards substrate modifications (54). It has become an important catalyst for the synthesis of sialosides. In addition, a heat-stable CSS has been cloned from Clostridium thermocellum (56).

Bacterial sialyltransferases are often expressed by pathogenic bacteria and are believed to be associated with bacterial virulence (3, 57–59). Bacterial sialyltransferases that have been cloned and expressed in E. coli include an Neisseria meningitidis α2–3-sialyltransferase (Lst) (60), an Neisseria gonorrhoeae α2–3-sialylatransferase (Lst) (60), an α2–8/2–9-polysialyltransferase from E. coli K92 (61), three sialyltransferases from Haemophilus influenzae (encoded by siaA, lic3A, and lsgB respectively) (62, 63), a Pasteurella multocida multi-functional sialyltransferase (PmST1) (64), two sialyltransferases from C. jejuni (Cst-I and Cst-II) (58, 65), two sialyltransferases from Haemophilus ducreyi (66, 67), a Vibrio sp. JT-FAJ-16 α2–3-sialyltransferase (68), and marine bacterial sialyltransferases including Photobacterium damsela α2–6-sialyltransferase (bst or Pd2,6ST) (69, 70), Photobacterium phosphoreum α2–3-sialyltransferase (71), and Photobacterium leiognathi JT-SHIZ-145 α2–6-sialyltransferase (72). Among these enzymes, many (e.g. PmST1, Pd2,6ST, and CstII) have high expression level and have been used in the efficient synthesis of α2–3- (64), α2–6- (73), and α2–8-linked sialosides (74). Another interesting feature of bacterial sialyltransferases is that many of them have multi-functionality. For example, α2–3-sialyltransferase, α2–6-sialyltransferase, α2–3-sialidase, and α2–3-trans-sialidase activities have been identified for PmST1 (64). Pd2,6ST has α2–6-sialidase and α2–6-trans-sialidase activities (75) in addition to its α2–6-sialyltransferase activity (69, 70, 73). In addition to α2–3-sialyltransferase and α2–8-sialyltransferase activities reported before for CstII (58), α2–8-sialidase and α2–8-trans-sialidase activities have been found (65). The presence of competing sialyltransferase and sialidase/trans-sialidase activities in the same enzyme may contribute to dynamic presentation of sialic acids or other nonulosonic acids by pathogenic bacteria.

Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Sialosides

The application of sialyltransferases and other related sialoside biosynthetic enzymes in the preparative-scale (19, 76–79) or large-scale synthesis of sialosides (80, 81) with or without in situ cofactor regeneration has been much explored in the last two decades. Engineered whole cells or enzymes entrapped in calcium pectate-silica-gel beads have also been used for the synthesis of CMP-sialic acid (82). Nevertheless, systematic synthesis of a large library of sialosides containing diverse sialic acid forms was not achieved until recently via the combination of chemical synthesis of sialic acid precursors and the use of recombinant bacterial sialoside biosynthetic enzymes with promiscuous substrate specificity.

One-pot multi-enzyme approaches

Efficient one-pot multi-enzyme systems have been developed for the synthesis of sialosides with diverse sialic acid forms, various sialyl linkages, and a variety of underlying glycans without the purification of intermediates. Such a method has been proven very efficient in the synthesis of sialoside libraries of great diversity. To do this, different sialic acid forms or their six-carbon precursors (N-acetylmannosamine, mannose, or their derivatives) can be chemically or enzymatically synthesized as sialyltransferase substrate precursors. These compounds can then be converted by CMP-sialic acid synthetase with or without a sialic acid aldolase to CMP-sialic acid, which will be used by sialyltransferases to transfer sialic acid to acceptors for the formation of naturally occurring sialosides or sialylglycoconjugates. Depending on the different types of sialyltransferases, naturally existing α2–3-, α2–6-, or α2–8-linked sialosides can be obtained (64, 65, 73, 83, 84). Typical yields for the preparative-scale (>20 mg) one-pot multi-enzyme synthesis are higher than 60%, many reactions can achieve more than 90% yields. Many sialosides synthesized have an alkyl azido aglycon which can be conveniently reduced to an amido group for efficient conjugation to proteins (85) or biotin (86) for biological studies of the importance of sialosides. Some have a para-nitrophenyl aglycon for high-throughput substrate specificity studies of sialidases (84).

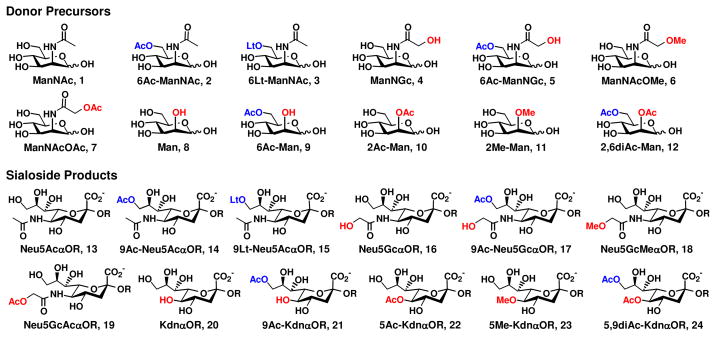

So far, sialosides containing 12 naturally occurring sialic acid forms (Figure 3) have been successfully synthesized from 12 sialic acid precursors including N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc), mannose, and their derivatives using the one-pot three-enzyme system. In addition, sialosides containing many non-natural sialic acid forms have also been obtained.

Figure 3.

Sialosides containing 12 naturally occurring sialic acid forms (13–24) that have been synthesized from sialic acid precursors (1–12) using a one-pot three-enzyme system.

Combinatorial chemoenzymatic synthesis of sialosides

The one-pot multi-enzyme chemoenzymatic approach described above is very efficient in obtaining structurally defined sialosides. However, the products have to be individually purified before being used in the functional studies. The purification step is tedious and time-consuming and is not necessary for initial ligand screening of sialoside-binding proteins. To avoid the product purification in generating a large library of sialosides, the Chen group developed a combinatorial chemoenzymatic approach, which can be combined directly with high-throughput screening without the product purification for evaluating the ligand specificity of sialic acid-binding proteins by changing the structure of sialic acid, the type of glycosidic linkages, and the underlying glycan structures (87). The strategy was to use biotinylated sialyltransferase acceptors and carry out the one-pot multi-enzyme reactions in microtiter plates. A hexa-ethylene glycol linker was used between the glycan and the biotin in the biotinylated glycans to minimize non-specific binding in the protein binding studies. After the completion of the enzymatic reactions, the reaction mixtures were transferred to NeutrAvidin-coated microtiter plates for protein binding assays. Each sample was plated in two sets of triplicates. One set was used for acceptor-binding protein assays to determine the reaction yields. The other set was used for sialic acid-binding protein assays. The data obtained can be adjusted by the yields obtained from the acceptor-binding protein assays to reflect the more accurate comparison of the sialoside structure-related protein binding. This approach for combined synthesis and high-throughput screening of a sialoside library to identify the preferred ligands for sialic acid-binding proteins has been demonstrated by the ligand specificity studies of Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA) and human Siglec 2 (CD22) using a library of 72 biotinylated α2–6-linked sialosides obtained from 18 sialic acid precursors and 4 biotinylated sialyltransferase acceptors (87).

Studies of Sialic Acid-Recognizing Proteins

Siglecs (Sialic Acid-binding Lectins of the Ig Superfamily)

Siglecs have emerged as the largest family of Sia-binding proteins thus far found in vertebrate systems, with 16 primate genes and 8 rodent genes being recognized to date (9, 10, 88). Since their initial discovery and formal naming about a decade ago there has been increasing interest in these molecules, as evidenced by the increasing numbers of recent literature references. The signature feature of all Siglecs is a Sia-binding domain contained in the amino terminal V-set Ig like domain. This binding pocket for Sias is well recognized to include a critical arginine residue that forms a salt bridge with the carboxylate of the Sia ligand. Siglecs also generally recognize the exocyclic C7–9 side chain of Sias. Other details of binding preference are more difficult to generalize, not only because they can vary greatly between Siglecs, but also because they tend to evolve rapidly e.g., between primates and rodents (9, 10, 88). Recent evidence has confirmed the hypothesis that engagement of the Sia-binding pocket by sialoglycans can modulate the signaling function of Siglecs (9, 10, 88). Thus, understanding the nature of the natural ligands for Siglecs (as opposed to just understanding their binding preferences on a microarray) becomes even more important. In this regard, recent evidence indicates that sulfate esters on the underlying glycan chains can also modify sialic acid recognition by the Siglecs (89–91).

Selectins

These are well-known Sia-binding proteins, which seem to only mainly require the negative charge of Sias, and even this can sometimes be replaced by sulfate ester at the same position of the underlying galactose residue (92–94). The real key to their binding properties is the presence of a Fuc residue in motifs such as sialyl Lewis x and sialyl Lewis a. Specific binding of selectins is further enhanced by sulfate esters on the C-6 position of an underlying Gal or GlcNAc residue (93). In at least one instance the binding of selectins requires not only the optimal cognate sialoglycan, but also adjacent sulfate esters on the polypeptide i.e. PSGL-1 recognition by P-Selectin (95). The goal of making synthetic ligands that can mimic and/or interrupt selection recognition function is being actively pursued, and recent evidence indicates that this may be possible in vivo.

Microbial Sialic Acid-Binding Proteins

The list of microbes, toxins and lectins that recognize sialoglycans grows almost by the day, and a full listing will not be attempted here. Relatively soon after the discovery of Sias, it was found that the influenza virus hemagglutinin binds Sias, and later that different linkages of Sias are recognized differentially by different influenza viruses (96). There is now further evidence that several such viruses recognize not only the linkage but also the types of Sias, and that these differences can determine the species preference of various viruses (97). However as with all Sia-binding phenomena, it should be kept in mind that the specifics are far more complex than a simple statement of which Sia type and linkage is preferred. Indeed, our recent work suggests that Sia recognition on cell surfaces can even be affected by non-sialylated glycans such as the ABH(O) blood groups (13), presumably because of carbohydrate-carbohydrate interactions between glycans, generating “clustered saccharide patches”. The extensive literature on the role of neuraminidase inhibitors in influenza (98) will not be reviewed here.

Sialyltransferases

Sialyltransferases (STs) (EC 2.4.99.X) are key enzymes in the biosynthesis of sialosides (sialic acid-containing oligosaccharides) and sialoglycoconjugates (sialic acid-containing glycoconjugates) (12, 99). They catalyze the reaction that transfers a sialic acid (N-acetylneuraminic acid or Neu5Ac) residue from its activated sugar nucleotide donor cytidine 5′-monophosphate sialic acid (CMP-sialic acid or CMP-Neu5Ac) to an acceptor, usually a structure terminated with a galactose, an N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), or another sialic acid residue. All sialyltransferases reported so far have been classified into five CAZy glycosyltransferase (GT) families including GT29, GT38, GT42, GT52, and GT80 based on their amino acid sequence similarities (CAZy – Carbohydrate-Active enZyme database, http://www.cazy.org/) (100, 101). Most mammalian sialyltransferases belong to GT29 family. Like other mammalian glycosyltransferases, mammalian sialyltransferases are type II membrane proteins with a trans-membrane domain of 16–20 residues. They are retained in Golgi lumen and many have a stem region of variable length (20–300 amino acids). The C-terminal catalytic domains have three major consensus sequence motifs called L, S, and VS sialylmotifs participating in binding to the sugar donor CMP-Neu5Ac, binding to both the donor and acceptor substrates, and catalysis, respectively. Recently, a new four-residue sialyl motif HY(Y/F/W)(D/E) was identified and shown to be essential for activity (102). No eukaryotic ST structures have been elucidated at the present time. Limited information has been known about their structure and mechanism of action (103).

On the other hand, bacterial sialyltransferases belong to GT38, GT42, GT52, and GT80 families and none of these display sequence homology to mammalian sialyltransferases. Crystal structures of four bacterial sialyltransferases have been reported including a multifunctional Campylobacter jejuni (OH4384) CstII (104) and a Campylobacter jejuni α2–3-sialyltransferase (CstI) (105) both belonging to CAZy family GT42, a multifunctional sialyltransferase (PmST1) from Pasteurella multocida strain P-1059 (106, 107) and an α2–6-sialyltransferase (Psp2,6ST) from Vibrionaceae Photobacterium sp. (108) both belonging to CAZy family GT80. While the structures of both CstII and CstI belong to glycosyltransferse-A (or glycosyltransferase-A-like) (GT-A) structure group (109) consisting of a single α/β/α sandwich resembling a Rossmann fold and a smaller lid-domain, the structures of both PmST1 and Psps2,6ST belong to glycosyltransferase-B (GT-B) structure group consisting of two Rossmann-like domains separated by a deep substrate-binding cleft (109).

Sialidases

Sialidases, or neuraminidases (EC 3.2.1.18), are sialic acid-releasing exoglycosidases that catalyze the removal of terminal sialic acids from sialosides and sialoglycoconjugates in nature (110). Many pathogens express sialidases either as receptor-destroying enzymes, e.g., the influenza virus, or to release cell surface Sias, either for nutritional purposes or to uncover underlying receptors (110). Again, the extensive literature on this subject will not be reviewed here. A special class of sialidases is trans-sialidases, which catalyze the cleavage of an existing sialosidic bond and the formation of a new sialosidic bond simultaneously. Trans-sialidase from Trypanosoma cruzi has been characterized in details (111, 112). Sialidases from influenza A and B viruses belong to CAZy glycoside hydrolase family 34 (GH34) while most bacterial and human sialidases, Trypanosoma rangeli sialidase, as well as Trypanosoma cruzi trans-sialidase are grouped into CAZy glycoside hydrolase family 33 (GH33). In addition, some bacterial sialyltransferases are multifunctional and have trans-sialidase and sialidase activities (63, 64). Endo-sialidases or endo-N-acetylneuraminidases (EC 3.2.1.129) have also been found from E. coli and Enterobacteria phages and have been grouped into CAZy glycoside hydrolase family 58 (GH58).

New Strategies for Sialobiology

Metabolic Engineering of Sialoglycoconjugates in vitro and in vivo

Metabolic engineering of sialoglycoconjugate in living cells and animals has become an efficient chemical glycobiology approach for exploring potential roles of sialic acids in biological systems. These have been achieved by metabolically incorporation of sialic acid derivatives and their precursors into cells, microorganism, and vertebrates and presented as non-natural sialic acid in the glycoconjugates mainly on cell surface (113–117). In some cases, non-natural sialic acid was used as terminators for polysialic acid chain elongation (118). In other cases, they were used to modulate and enhance the immunogenicity of the glycan-based cancer vaccines (119–122). Some of the compounds with a bioorthogonal functional group (123) can be used as efficient probes to visualize glycan expression changes in living cells and animals (116, 124–126). A noticeable example is azido group which is a common functional group introduced into Neu5Ac or ManNAc to produce glycan probes N-azidoacetylneuramic acid (Neu5Az) or N-azidoacetylmannosamine (ManNAz). They are commonly per-acetylated for efficient incorporation into cells. After feeding the cells, microorganisms, or vertebrates with the per-acetylated Neu5Az or ManNAz, the resulted cell surface modified sialic acid can be selectively probed with fluorescent or other tags for imaging or further analysis (125, 127).

Glycan primers containing a hydrophobic aglycon can also be used as glycosyltransferase acceptor decoys to perturb the production of cellular glycans (128–130), therefore are useful probes to study the functions of different glycans and glycosyltransferases.

Sialoglycan Microarrays

In recent years there have been many reports of glycan microarrays, in which large numbers of glycans of different structures are arrayed on slides and probed with various putative or known glycan-binding proteins (8, 10). While most of these arrays include sialylated glycans, the vast majority carry only the common human Sia Neu5Ac, with occasional representations of Neu5Gc (131, 132) and no examples of Sia O-acetylation or other modifications. Many glycans currently on arrays could potentially be modified by each of many kinds of Sias and in many possible types of linkages. Thus, if the natural diversity of Sias and their linkages were taken into account, representative arrays would have to consist of thousands of possible glycans. As this is not practically feasible at the present time, we and others have been making arrays that are purely focused on certain types of terminal Sias presented on a relatively limited number of possible underlying glycans. Two such arrays are currently under study. In this regard, one practical problem is that Sia O-acetyl esters are somewhat labile and can be partially eliminated during the process of coupling and processing of slides. Thus, a given spot on an array may be presenting both the O-acetylated and non O-acetylated versions. And of course, all of these derivatives only represent C-9 O-acetylation. The more evanescent 7-O-acetyl ester that can migrate from C-7 to the C-9 (133, 134) is at the present time almost impossible to synthesize and very difficult to study in isolation (135).

Perspectives and Future Directions

This has been a brief and incomplete survey of a rapidly advancing field, at the interface of chemistry and biology. The future appears bright for studies of sialic acids, especially at this interface. We need to expand and probe existing sialoside microarrays to better represent the diversity found in nature. It would also be worthwhile to generate both arrays of natural and non-natural sialosides. Combinations of such arrays can tell us much about the binding specificities of the many sialic acid-binding proteins that have been identified to date. The apparent roles of Neu5Gc and anti-Neu5Gc antibodies in cancer and other diseases (136, 137) also deserve further exploration, as do the roles of sialic acids as targets for various pathogens.

Acknowledgments

X.C. is grateful for financial support from NIH R01GM076360, NIH U01CA128442, NSF CHE0548235, and the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation. X.C. is an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow, a Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar, and a UC-Davis Chancellor’s Fellow. A.V. is grateful for financial support from NIH grants P01HL57345 and U01CA128442, and from the Mathers Foundation of New York.

References

- 1.Traving C, Schauer R. Structure, function and metabolism of sialic acids. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1998;54:1330–1349. doi: 10.1007/s000180050258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Troy FA., 2nd Polysialylation: from bacteria to brains. Glycobiology. 1992;2:5–23. doi: 10.1093/glycob/2.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angata T, Varki A. Chemical diversity in the sialic acids and related alpha-keto acids: an evolutionary perspective. Chem Rev. 2002;102:439–469. doi: 10.1021/cr000407m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knirel YA, Shashkov AS, Tsvetkov YE, Jansson PE, Zahringer U. 5,7-diamino-3,5,7,9-tetradeoxynon-2-ulosonic acids in bacterial glycopolymers: chemistry and biochemistry. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem. 2003;58:371–417. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2318(03)58007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vimr ER, Kalivoda KA, Deszo EL, Steenbergen SM. Diversity of microbial sialic acid metabolism. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:132–153. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.1.132-153.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoenhofen IC, Vinogradov E, Whitfield DM, Brisson JR, Logan SM. The CMP-legionaminic acid pathway in Campylobacter: biosynthesis involving novel GDP-linked precursors. Glycobiology. 2009;19:715–725. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis AL, Desa N, Hansen EE, Knirel YA, Gordon JI, Gagneux P, Nizet V, Varki A. Innovations in host and microbial sialic acid biosynthesis revealed by phylogenomic prediction of nonulosonic acid structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13552–13557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902431106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schauer R. Sialic acids as regulators of molecular and cellular interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.06.003. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varki A, Angata T. Siglecs – the major subfamily of I-type lectins. Glycobiology. 2006;16:1R–27R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varki A. Glycan-based interactions involving vertebrate sialic-acid-recognizing proteins. Nature. 2007;446:1023–1029. doi: 10.1038/nature05816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varki A. Multiple changes in sialic acid biology during human evolution. Glycoconj J. 2009;26:231–245. doi: 10.1007/s10719-008-9183-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harduin-Lepers A, Mollicone R, Delannoy P, Oriol R. The animal sialyltransferases and sialyltransferase-related genes: a phylogenetic approach. Glycobiology. 2005;15:805–817. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwi063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen M, Hurtado-Ziola N, Varki A. ABO blood group glycans modulate sialic acid recognition on erythrocytes. Blood. 2009;114:3668–3676. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-227041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schauer R, Srinivasan GV, Coddeville B, Zanetta JP, Guerardel Y. Low incidence of N-glycolylneuraminic acid in birds and reptiles and its absence in the platypus. Carbohydr Res. 2009;344:1494–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis AL, Nizet V, Varki A. Discovery and characterization of sialic acid O-acetylation in group B Streptococcus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11123–11128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403010101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ram S, Sharma AK, Simpson SD, Gulati S, McQuillen DP, Pangburn MK, Rice PA. A novel sialic acid binding site on factor H mediates serum resistance of sialylated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Exp Med. 1998;187:743–752. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlin AF, Uchiyama S, Chang YC, Lewis AL, Nizet V, Varki A. Molecular mimicry of host sialylated glycans allows a bacterial pathogen to engage neutrophil Siglec-9 and dampen the innate immune response. Blood. 2009;113:3333–3336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-187302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varki A. Sialic acids in human health and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:351–360. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halcomb RL, Chappell MD. Recent developments in technology for glycosylation with sialic acid. J Carbohydr Chem. 2002;21:723–768. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boons GJ, Demchenko AV. Recent advances in O-sialylation. Chem Rev. 2000;100:4539–4566. doi: 10.1021/cr990313g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiefel MJ, von Itzstein M. Recent advances in the synthesis of sialic acid derivatives and sialylmimetics as biological probes. Chem Rev. 2002;102:471–490. doi: 10.1021/cr000414a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demchenko AV, Boons GJ. A novel and versatile glycosyl donor for the preparation of glycosides of N-acetylneuraminic acid. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:3065–3068. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demchenko AV, Boons GJ. A novel direct glycosylation approach for the synthesis of dimers of N-acetylneuraminic acid. Chem Eur J. 1999;5:1278–1283. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu CS, Niikura K, Lin CC, Wong CH. The thioglycoside and glycosyl phosphite of 5-azido sialic acid: Excellent donors for the alpha-glycosylation of primary hydroxy groups. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:2900–2903. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010803)40:15<2900::AID-ANIE2900>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komba S, Galustian C, Ishida H, Feizi T, Kannagi R, Kiso M. Synthetic studies on sialoglycoconjugates part 109 - The first total synthesis of 6-sulfo-de-N-acetylsialyl Lewis(x) ganglioside: A superior ligand for human L-selectin. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1999;38:1131–1133. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990419)38:8<1131::AID-ANIE1131>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Meo C, Demchenko AV, Boons GJ. A stereoselective approach for the synthesis of alpha-sialosides. J Org Chem. 2001;66:5490–5497. doi: 10.1021/jo010345f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ando H, Koike Y, Ishida H, Kiso M. Extending the possibility of an N-Troc-protected sialic acid donor toward variant sialo-glycoside synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:6883–6886. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adachi M, Tanaka H, Takahashi T. An effective sialylation method using N-Troc- and N-Fmoc-protected beta-thiophenyl sialosides and application to the one-pot two-step synthesis of 2,6-sialyl-T antigen. Synlett. 2004:609–614. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren CT, Chen CS, Wu SH. Synthesis of a sialic acid dimmer derivative, 2′-α-O-benzyl Neu5Ac-α-(2→5)Neu5Gc. J Org Chem. 2002;67:1376–1379. doi: 10.1021/jo015930v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka H, Takashi G, Fukase K. Highly efficient sialylation towards α(2–3)- and α(2–6)-Neu5Ac-Gal synthesis: significant “fixed dipole effect” of N-phthalyl group on α-selectivity. Synlett. 2005;2005:2958–2962. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ye D, Liu W, Zhang D, Feng E, Jiang H, Liu H. Efficient dehydrative sialylation of C-4-aminated sialyl-hemiketal donors with Ph2SO/Tf2O. J Org Chem. 2009;74:1733–1735. doi: 10.1021/jo802396a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka H, Nishiura Y, Takahashi T. Stereoselective synthesis of oligo-alpha-(2,8)-sialic acids. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7124–7125. doi: 10.1021/ja0613613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka H, Nishiura Y, Takahashi T. An efficient convergent synthesis of GP1c ganglioside epitope. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17244–17245. doi: 10.1021/ja807482t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crich D, Li W. alpha-selective sialylations at −78 degrees C in nitrile solvents with a 1-adamantanyl thiosialoside. J Org Chem. 2007;72:7794–7797. doi: 10.1021/jo7012912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crich D, Li W. O-sialylation with N-acetyl-5-N,4-O-carbonyl-protected thiosialoside donors in dichloromethane: facile and selective cleavage of the oxazolidinone ring. J Org Chem. 2007;72:2387–2391. doi: 10.1021/jo062431r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crich D, Wu B. Stereoselective iterative one-pot synthesis of N-glycolylneuraminic acid-containing oligosaccharides. Org Lett. 2008;10:4033–4035. doi: 10.1021/ol801548k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haberman JM, Gin DY. A new C(1)-auxiliary for anomeric stereocontrol in the synthesis of alpha-sialyl glycosides. Org Lett. 2001;3:1665–1668. doi: 10.1021/ol015854i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haberman JM, Gin DY. Dehydrative sialylation with C2-hemiketal sialyl donors. Org Lett. 2003;5:2539–2541. doi: 10.1021/ol034815z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai S, Yu B. Efficient sialylation with phenyltrifluoroacetimidates as leaving groups. Org Lett. 2003;5:3827–3830. doi: 10.1021/ol0353161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ando H, Koike Y, Koizumi S, Ishida H, Kiso M. 1,5-Lactamized sialyl acceptors for various disialoside syntheses: novel method for the synthesis of glycan portions of Hp-s6 and HLG-2 gangliosides. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:6759–6763. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka H, Ando H, Ishida H, Kiso M, Ishihara H, Koketsu M. Synthetic study on alpha(2 → 8)-linked oligosialic acid employing 1,5-lactamization as a key step. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:4478–4481. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanashima S, Castagner B, Esposito D, Nokami T, Seeberger PH. Synthesis of a sialic acid alpha(2–3) galactose building block and its use in a linear synthesis of sialyl Lewis X. Org Lett. 2007;9:1777–1779. doi: 10.1021/ol0704946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun B, Srinivasan B, Huang X. Pre-activation-based one-pot synthesis of an alpha-(2,3)-sialylated core-fucosylated complex type bi-antennary N-glycan dodecasaccharide. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:7072–7081. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Endo T, Koizumi S, Tabata K, Ozaki A. Large-scale production of CMP-NeuAc and sialylated oligosaccharides through bacterial coupling. Appl Microbiol Biotech. 2000;53:257–261. doi: 10.1007/s002530050017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dumon C, Bosso C, Utille JP, Heyraud A, Samain E. Production of Lewis x tetrasaccharides by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:359–365. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Priem B, Gilbert M, Wakarchuk WW, Heyraud A, Samain E. A new fermentation process allows large-scale production of human milk oligosaccharides by metabolically engineered bacteria. Glycobiology. 2002;12:235–240. doi: 10.1093/glycob/12.4.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Antoine T, Priem B, Heyraud A, Greffe L, Gilbert M, Wakarchuk WW, Lam JS, Samain E. Large-scale in vivo synthesis of the carbohydrate moieties of gangliosides GM1 and GM2 by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:406–412. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200200540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fort S, Birikaki L, Dubois MP, Antoine T, Samain E, Driguez H. Biosynthesis of conjugatable saccharidic moieties of GM2 and GM3 gangliosides by engineered E. coli. Chem Commun (Camb) 2005:2558–2560. doi: 10.1039/b500686d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fierfort N, Samain E. Genetic engineering of Escherichia coli for the economical production of sialylated oligosaccharides. J Biotech. 2008;134:261–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mehta S, Gilbert M, Wakarchuk WW, Whitfield DM. Ready access to sialylated oligosaccharide donors. Org Lett. 2000;2:751–753. doi: 10.1021/ol990406k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan F, Mehta S, Eichler E, Wakarchuk WW, Gilbert M, Schur MJ, Whitfield DM. Simplifying oligosaccharide synthesis: efficient synthesis of lactosamine and siaylated lactosamine oligosaccharide donors. J Org Chem. 2003;68:2426–2431. doi: 10.1021/jo026569v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cao H, Huang S, Cheng J, Li Y, Muthana S, Son B, Chen X. Chemical preparation of sialyl Lewis x using an enzymatically synthesized sialoside building block. Carbohydr Res. 2008;343:2863–2869. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayashi M, Tanaka M, Itoh M, Miyauchi H. A Convenient and Efficient Synthesis of SLeX Analogs. J Org Chem. 1996;61:2938–2945. doi: 10.1021/jo960125f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu H, Yu H, Karpel R, Chen X. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of CMP-sialic acid derivatives by a one-pot two-enzyme system: comparison of substrate flexibility of three microbial CMP-sialic acid synthetases. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:6427–6435. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Y, Yu H, Cao H, Lau K, Muthana S, Tiwari VK, Son B, Chen X. Pasteurella multocida sialic acid aldolase: a promising biocatalyst. Appl Microbiol Biotech. 2008;79:963–970. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1506-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mizanur RM, Pohl NL. Cloning and characterization of a heat-stable CMP-N-acylneuraminic acid synthetase from Clostridium thermocellum. Appl Microbiol Biotech. 2007;76:827–834. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schauer R. Achievements and challenges of sialic acid research. Glycoconj J. 2000;17:485–499. doi: 10.1023/A:1011062223612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gilbert M, Brisson JR, Karwaski MF, Michniewicz J, Cunningham AM, Wu Y, Young NM, Wakarchuk WW. Biosynthesis of ganglioside mimics in Campylobacter jejuni OH4384. Identification of the glycosyltransferase genes, enzymatic synthesis of model compounds, and characterization of nanomole amounts by 600-MHz (1)H and (13)C NMR analysis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3896–3906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.3896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith H, Parsons NJ, Cole JA. Sialylation of neisserial lipopolysaccharide: a major influence on pathogenicity. Microb Pathog. 1995;19:365–377. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1995.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gilbert M, Watson DC, Cunningham AM, Jennings MP, Young NM, Wakarchuk WW. Cloning of the lipooligosaccharide alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase from the bacterial pathogens Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28271–28276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shen GJ, Datta AK, Izumi M, Koeller KM, Wong CH. Expression of alpha 2,8/2,9-polysialyltransferase from Escherichia coli K92 - Characterization of the enzyme and its reaction products. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:35139–35146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hood DW, Cox AD, Gilbert M, Makepeace K, Walsh S, Deadman ME, Cody A, Martin A, Mansson M, Schweda EK, Brisson JR, Richards JC, Moxon ER, Wakarchuk WW. Identification of a lipopolysaccharide alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase from Haemophilus influenzae. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:341–350. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jones PA, Samuels NM, Phillips NJ, Munson RS, Jr, Bozue JA, Arseneau JA, Nichols WA, Zaleski A, Gibson BW, Apicella MA. Haemophilus influenzae type b strain A2 has multiple sialyltransferases involved in lipooligosaccharide sialylation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14598–14611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110986200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu H, Chokhawala H, Karpel R, Yu H, Wu B, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Jia Q, Chen X. A multifunctional Pasteurella multocida sialyltransferase: a powerful tool for the synthesis of sialoside libraries. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17618–17619. doi: 10.1021/ja0561690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng J, Yu H, Lau K, Huang S, Chokhawala HA, Li Y, Tiwari VK, Chen X. Multifunctionality of Campylobacter jejuni sialyltransferase CstII: characterization of GD3/GT3 oligosaccharide synthase, GD3 oligosaccharide sialidase, and trans-sialidase activities. Glycobiology. 2008;18:686–697. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li Y, Sun M, Huang S, Yu H, Chokhawala HA, Thon V, Chen X. The Hd0053 gene of Haemophilus ducreyi encodes an alpha2,3-sialyltransferase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361:555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bozue JA, Tullius MV, Wang J, Gibson BW, Munson RS., Jr Haemophilus ducreyi produces a novel sialyltransferase. Identification of the sialyltransferase gene and construction of mutants deficient in the production of the sialic acid-containing glycoform of the lipooligosaccharide. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4106–4114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takakura Y, Tsukamoto H, Yamamoto T. Molecular cloning, expression and properties of an alpha/beta-Galactoside alpha2,3-sialyltransferase from Vibrio sp JT-FAJ-16. J Biochem. 2007;142:403–412. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamamoto T, Nakashizuka M, Terada I. Cloning and expression of a marine bacterial beta-galactoside alpha2,6-sialyltransferase gene from Photobacterium damsela JT0160. J Biochem. 1998;123:94–100. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun M, Li Y, Chokhawala HA, Henning R, Chen X. N-Terminal 112 amino acid residues are not required for the sialyltransferase activity of Photobacterium damsela alpha2,6-sialyltransferase. Biotech Lett. 2008;30:671–676. doi: 10.1007/s10529-007-9588-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsukamoto H, Takakura Y, Yamamoto T. Purification, cloning, and expression of an alpha/beta-galactoside alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase from a luminous marine bacterium Photobacterium phosphoreum. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29794–29802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701907200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yamamoto T, Hamada Y, Ichikawa M, Kajiwara H, Mine T, Tsukamoto H, Takakura Y. A beta-galactoside alpha2,6-sialyltransferase produced by a marine bacterium Photobacterium leiognathi JT-SHIZ-145, is active at pH 8. Glycobiology. 2007;17:1167–1174. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yu H, Huang S, Chokhawala H, Sun M, Zheng H, Chen X. Highly efficient chemoenzymatic synthesis of naturally occurring and non-natural alpha-2,6-linked sialosides: A P. damsela alpha-2,6-Sialyltransferase with extremely flexible donor-substrate specificity. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:3938–3944. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yu H, Cheng J, Ding L, Khedri Z, Chen Y, Chin S, Lau K, Tiwari VK, Chen X. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of GD3 oligosaccharides and other disialyl glycans containing natural and non-natural sialic acids. J Am Chem Soc. 2009 doi: 10.1021/ja907750r.. Published on line November 30 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheng J, Huang S, Yu H, Li Y, Lau K, Chen X. Trans-sialidase activity of Photobacterium damsela α2,6-sialyltransferase and its application in the synthesis of sialosides. Glycobiology. 2009 doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp172.. Published on line Oct. 30, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ito Y, Paulson JC. Combined use of trans-sialidase and sialyltransferase for enzymatic synthesis of alphaNeuAc2–3-beta-Gal-OCH2CH2SiMe3. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:7862–6863. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ichikawa Y, Lin YC, Dumas DP, Shen GJ, Garciajunceda E, Williams MA, Bayer R, Ketcham C, Walker LE, Paulson JC, Wong CH. Chemical-enzymatic synthesis and conformational-analysis of sialyl Lewis-X and derivatives. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:9283–9298. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ichikawa Y, Liu JLC, Shen GJ, Wong CH. A hHighly efficient multienzyme system for the one-step synthesis of a sialyl trisaccharide – in situ generation of sialic-acid and N-acetyllactosamine coupled with regeneration of UDP-glucose, UDP-galactose, and CMP-sialic acid. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:6300–6302. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ichikawa Y, Shen GJ, Wong CH. Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of sialyl oligosaccharide with in situ regeneration of CMP-sialic acid. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:4698–4700. [Google Scholar]

- 809.Gilbert M, Bayer R, Cunningham AM, DeFrees S, Gao Y, Watson DC, Young NM, Wakarchuk WW. The synthesis of sialylated oligosaccharides using a CMP-Neu5Ac synthetase/sialyltransferase fusion. Nat Biotech. 1998;16:769–772. doi: 10.1038/nbt0898-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Johnson KF. Synthesis of oligosaccharides by bacterial enzymes. Glycoconj J. 1999;16:141–146. doi: 10.1023/a:1026440509859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nahalka J, Wu B, Shao J, Gemeiner P, Wang PG. Production of cytidine 5′-monophospho-N-acetyl-beta-D-neuraminic acid (CMP-sialic acid) using enzymes or whole cells entrapped in calcium pectate-silica-gel beads. Biotech Appl Biochem. 2004;40:101–106. doi: 10.1042/BA20030159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yu H, Chokhawala HA, Huang S, Chen X. One-pot three-enzyme chemoenzymatic approach to the synthesis of sialosides containing natural and non-natural functionalities. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2485–2492. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chokhawala HA, Yu H, Chen X. High-throughput substrate specificity studies of sialidases by using chemoenzymatically synthesized sialoside libraries. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:194–201. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yu H, Chokhawala HA, Varki A, Chen X. Efficient chemoenzymatic synthesis of biotinylated human serum albumin-sialoglycoside conjugates containing O-acetylated sialic acids. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:2458–2463. doi: 10.1039/b706507h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Linman MJ, Taylor JD, Yu H, Chen X, Cheng Q. Surface plasmon resonance study of protein-carbohydrate interactions using biotinylated sialosides. Anal Chem. 2008;80:4007–4013. doi: 10.1021/ac702566e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chokhawala HA, Huang S, Lau K, Yu H, Cheng J, Thon V, Hurtado-Ziola N, Guerrero JA, Varki A, Chen X. Combinatorial chemoenzymatic synthesis and high-throughput screening of sialosides. ACS Chem Biol. 2008;3:567–576. doi: 10.1021/cb800127n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Crocker PR, Paulson JC, Varki A. Siglecs and their roles in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:255–266. doi: 10.1038/nri2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bochner BS, Alvarez RA, Mehta P, Bovin NV, Blixt O, White JR, Schnaar RL. Glycan array screening reveals a candidate ligand for Siglec-8. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4307–4312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Campanero-Rhodes MA, Childs RA, Kiso M, Komba S, Le Narvor C, Warren J, Otto D, Crocker PR, Feizi T. Carbohydrate microarrays reveal sulphation as a modulator of siglec binding. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:1141–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kimura N, Ohmori K, Miyazaki K, Izawa M, Matsuzaki Y, Yasuda Y, Takematsu H, Kozutsumi Y, Moriyama A, Kannagi R. Human B-lymphocytes express alpha2–6-sialylated 6-sulfo-N-acetyllactosamine serving as a preferred ligand for CD22/Siglec-2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32200–32207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Varki A. Selectin ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:7390–7397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rosen SD, Bertozzi CR. Two selectins converge on sulphate. Leukocyte adhesion. Curr Biol. 1996;6:261–264. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00473-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kansas GS. Selectins and their ligands: current concepts and controversies. Blood. 1996;88:3259–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.McEver RP, Cummings RD. Role of PSGL-1 binding to selectins in leukocyte recruitment. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:S97–S103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rogers GN, Paulson JC, Daniels RS, Skehel JJ, Wilson IA, Wiley DC. Single amino acid substitutions in influenza haemagglutinin change receptor binding specificity. Nature. 1983;304:76–78. doi: 10.1038/304076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nicholls JM, Chan RW, Russell RJ, Air GM, Peiris JS. Evolving complexities of influenza virus and its receptors. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.von Itzstein M. The war against influenza: discovery and development of sialidase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:967–974. doi: 10.1038/nrd2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Harduin-Lepers A, Recchi MA, Delannoy P. 1994, the year of sialyltransferases. Glycobiology. 1995;5:741–758. doi: 10.1093/glycob/5.8.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Campbell JA, Davies GJ, Bulone V, Henrissat B. A classification of nucleotide-diphospho-sugar glycosyltransferases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1997;326:929–939. doi: 10.1042/bj3260929u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Coutinho PM, Deleury E, Davies GJ, Henrissat B. An evolving hierarchical family classification for glycosyltransferases. J Mol Biol. 2003;328:307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jeanneau C, Chazalet V, Auge C, Soumpasis DM, Harduin-Lepers A, Delannoy P, Imberty A, Breton C. Structure-function analysis of the human sialyltransferase ST3Gal I: role of N-glycosylation and a novel conserved sialylmotif. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13461–13468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311764200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Harduin-Lepers A, Vallejo-Ruiz V, Krzewinski-Recchi MA, Samyn-Petit B, Julien S, Delannoy P. The human sialyltransferase family. Biochimie. 2001;83:727–737. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chiu CP, Watts AG, Lairson LL, Gilbert M, Lim D, Wakarchuk WW, Withers SG, Strynadka NC. Structural analysis of the sialyltransferase CstII from Campylobacter jejuni in complex with a substrate analog. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:163–170. doi: 10.1038/nsmb720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chiu CP, Lairson LL, Gilbert M, Wakarchuk WW, Withers SG, Strynadka NC. Structural analysis of the alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase Cst-I from Campylobacter jejuni in apo and substrate-analogue bound forms. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7196–7204. doi: 10.1021/bi602543d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ni L, Chokhawala HA, Cao H, Henning R, Ng L, Huang S, Yu H, Chen X, Fisher AJ. Crystal structures of Pasteurella multocida sialyltransferase complexes with acceptor and donor analogues reveal substrate binding sites and catalytic mechanism. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6288–6298. doi: 10.1021/bi700346w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ni L, Sun M, Yu H, Chokhawala H, Chen X, Fisher AJ. Cytidine 5′-monophosphate (CMP)-induced structural changes in a multifunctional sialyltransferase from Pasteurella multocida. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2139–2148. doi: 10.1021/bi0524013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kakuta Y, Okino N, Kajiwara H, Ichikawa M, Takakura Y, Ito M, Yamamoto T. Crystal structure of Vibrionaceae Photobacterium sp. JT-ISH-224 alpha2,6-sialyltransferase in a ternary complex with donor product CMP and acceptor substrate lactose: catalytic mechanism and substrate recognition. Glycobiology. 2008;18:66–73. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Breton C, Snajdrova L, Jeanneau C, Koca J, Imberty A. Structures and mechanisms of glycosyltransferases. Glycobiology. 2006;16:29R–37R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Corfield T. Bacterial sialidases – roles in pathogenicity and nutrition. Glycobiology. 1992;2:509–521. doi: 10.1093/glycob/2.6.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Damager I, Buchini S, Amaya MF, Buschiazzo A, Alzari P, Frasch AC, Watts A, Withers SG. Kinetic and mechanistic analysis of Trypanosoma cruzi trans-sialidase reveals a classical ping-pong mechanism with acid/base catalysis. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3507–3512. doi: 10.1021/bi7024832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Amaya MF, Watts AG, Damager I, Wehenkel A, Nguyen T, Buschiazzo A, Paris G, Frasch AC, Withers SG, Alzari PM. Structural insights into the catalytic mechanism of Trypanosoma cruzi trans-sialidase. Structure. 2004;12:775–784. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wieser JR, Heisner A, Stehling P, Oesch F, Reutter W. In vivo modulated N-acyl side chain of N-acetylneuraminic acid modulates the cell contact-dependent inhibition of growth. FEBS Lett. 1996;395:170–173. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schmidt C, Stehling P, Schnitzer J, Reutter W, Horstkorte R. Biochemical engineering of neural cell surfaces by the synthetic N-propanoyl-substituted neuraminic acid precursor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19146–19152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mahal LK, Yarema KJ, Bertozzi CR. Engineering chemical reactivity on cell surfaces through oligosaccharide biosynthesis. Science. 1997;276:1125–1128. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Prescher JA, Dube DH, Bertozzi CR. Chemical remodelling of cell surfaces in living animals. Nature. 2004;430:873–877. doi: 10.1038/nature02791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Dube DH, Bertozzi CR. Glycans in cancer and inflammation–potential for therapeutics and diagnostics. Nat Rev. 2005;4:477–488. doi: 10.1038/nrd1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mahal LK, Charter NW, Angata K, Fukuda M, Koshland DE, Jr, Bertozzi CR. A small-molecule modulator of poly-alpha 2,8-sialic acid expression on cultured neurons and tumor cells. Science. 2001;294:380–381. doi: 10.1126/science.1062192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Krug LM, Ragupathi G, Ng KK, Hood C, Jennings HJ, Guo Z, Kris MG, Miller V, Pizzo B, Tyson L, Baez V, Livingston PO. Vaccination of small cell lung cancer patients with polysialic acid or N-propionylated polysialic acid conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:916–923. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wu J, Guo Z. Improving the antigenicity of sTn antigen by modification of its sialic acid residue for development of glycoconjugate cancer vaccines. Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17:1537–1544. doi: 10.1021/bc060103s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chefalo P, Pan Y, Nagy N, Guo Z, Harding CV. Efficient metabolic engineering of GM3 on tumor cells by N-phenylacetyl-D-mannosamine. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3733–3739. doi: 10.1021/bi052161r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chefalo P, Pan Y, Nagy N, Harding C, Guo Z. Preparation and immunological studies of protein conjugates of N-acylneuraminic acids. Glycoconj J. 2004;20:407–414. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000033997.01760.b9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hang HC, Bertozzi CR. Chemoselective approaches to glycoprotein assembly. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:727–736. doi: 10.1021/ar9901570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dube DH, Prescher JA, Quang CN, Bertozzi CR. Probing mucin-type O-linked glycosylation in living animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4819–4824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506855103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Codelli JA, Baskin JM, Agard NJ, Bertozzi CR. Second-generation difluorinated cyclooctynes for copper-free click chemistry. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11486–11493. doi: 10.1021/ja803086r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zeng Y, Ramya TN, Dirksen A, Dawson PE, Paulson JC. High-efficiency labeling of sialylated glycoproteins on living cells. Nat Methods. 2009;6:207–209. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Saxon E, Bertozzi CR. Cell surface engineering by a modified Staudinger reaction. Science. 2000;287:2007–2010. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Sarkar AK, Fritz TA, Taylor WH, Esko JD. Disaccharide uptake and priming in animal cells: inhibition of sialyl Lewis X by acetylated Gal beta1→4GlcNAc beta-O-naphthalenemethanol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3323–3327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sarkar AK, Rostand KS, Jain RK, Matta KL, Esko JD. Fucosylation of disaccharide precursors of sialyl Lewis X inhibit selectin-mediated cell adhesion. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25608–25616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Fritz TA, Esko JD. Xyloside priming of glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis and inhibition of proteoglycan assembly. Methods Mol Biol. 2001;171:317–323. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-209-0:317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Taylor ME, Drickamer K. Paradigms for glycan-binding receptors in cell adhesion. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:572–577. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lugovtsev VY, Smith DF, Weir JP. Changes of the receptor-binding properties of influenza B virus B/Victoria/504/2000 during adaptation in chicken eggs. Virology. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.08.014. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Varki A, Diaz S. The release and purification of sialic acids from glycoconjugates: methods to minimize the loss and migration of O-acetyl groups. Anal Biochem. 1984;137:236–247. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kamerling JP, Schauer R, Shukla AK, Stoll S, Van Halbeek H, Vliegenthart JF. Migration of O-acetyl groups in N,O-acetylneuraminic acids. Eur J Biochem. 1987;162:601–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb10681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Weiman S, Dahesh S, Carlin AF, Varki A, Nizet V, Lewis AL. Genetic and biochemical modulation of sialic acid O-acetylation on group B Streptococcus: phenotypic and functional impact. Glycobiology. 2009;19:1204–1213. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hedlund M, Padler-Karavani V, Varki NM, Varki A. Evidence for a human-specific mechanism for diet and antibody-mediated inflammation in carcinoma progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18936–18941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803943105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Pham T, Gregg CJ, Karp F, Chow R, Padler-Karavani V, Cao H, Chen X, Witztum JL, Varki NM, Varki A. Evidence for a novel human-specific xeno-auto-antibody response against vascular endothelium. Blood. 2009;114:5225–5235. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]