Abstract

Objective

While most septic patients have an underlying comorbidity, most animal models of sepsis use mice that were healthy prior to the onset of infection. Malignancy is the most common comorbidity associated with sepsis. The purpose of this study was to determine whether mice with cancer have a different response to sepsis than healthy animals.

Design

Prospective, randomized controlled study.

Setting

Animal laboratory in a university medical center.

Subjects

C57Bl/6 mice.

Interventions

Animals received a subcutaneous injection of either 250,000 cells of the transplantable pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line Pan02 (cancer) or phosphate-buffered saline (healthy). Three weeks later, mice given Pan02 cells developed reproducible, non-metastatic tumors. Both groups of mice then underwent intratracheal injection of either Pseudomonas aeruginosa (septic) or 0.9% NaCl (sham). Animals were sacrificed 24 hours post-operatively or followed seven days for survival.

Measurements and Main Results

Cancer and healthy mice appeared similar when subjected to sham operation, although cancer animals had lower levels of T and B lymphocyte apoptosis. Cancer septic mice had increased mortality compared to previously healthy septic mice subjected to the identical injury (52% vs. 28%, p=0.04). This was associated with increased bacteremia but no difference in local pulmonary infection. Cancer septic mice also had increased intestinal epithelial apoptosis. Although sepsis induced an increase in T and B lymphocyte apoptosis in all animals, cancer septic mice had decreased T and B lymphocyte apoptosis compared to previously healthy septic mice. Serum and pulmonary cytokines, lung histology, complete blood counts and intestinal proliferation were similar between cancer septic and previously healthy septic mice.

Conclusions

When subjected to the same septic insult, mice with cancer have increased mortality compared to previously healthy animals. Decreased systemic bacterial clearance and alterations in both intestinal epithelial and lymphocyte apoptosis may help explain this differential response.

Keywords: Sepsis, pneumonia, apoptosis, comorbidity, pancreatic cancer, cytokine

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis affects over 750,000 people in the United States annually and is a leading cause of death in critically ill patients (1). Since most patients who develop sepsis have one or more pre-existing comorbidities, sepsis should not be considered a disease which strikes randomly, but instead one that most commonly affects patients who already have some type of chronic illness (1).

Multiple chronic comorbidities increase mortality in patients with sepsis and in experimental models of the disease (1-4). Of these, cancer represents the most common comorbidity in septic patients. Cancer is also the comorbidity associated with the highest risk of death in sepsis, with mortalities of 37% in patients with non-metastatic disease and 43% in patients with metastatic disease (1;5). Of note, cancer patients are nearly ten times more likely to develop sepsis than patients without malignancy (6). The etiology behind the increased mortality seen in cancer patients who develop sepsis compared to healthy patients who develop sepsis appears to be multifactorial (6;7). Reasons include impaired leukocyte function secondary to the underlying malignancy itself and immunosuppression secondary to cancer treatment (chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immune modulators). Additionally, patients with cancer are prone to having additional chronic comorbid conditions. Among all cancer patients, those with pancreatic cancer have the highest incidence of sepsis, at a rate of over 14,000 cases per 100,000 patients (6).

There are limited models currently available to understand the interaction between cancer and sepsis. This is because most animal models of sepsis use mice that are healthy prior to the onset of infection despite the facts that a) this represents the patient population least likely to develop or die from sepsis, and b) most patients with sepsis have pre-existing comorbidities. It is unclear if healthy mice are appropriate surrogates for patients with pre-existing comorbidities. This may be one reason (of many) why positive experimental findings in animal models of sepsis almost never translate into positive clinical trials in patients (8-11). To better understand potential mechanisms responsible for why cancer increases mortality in sepsis, we developed a novel model of pneumonia in mice with cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cancer and sepsis models

Cancer was induced via injection of the transplantable mouse pancreas adenocarcinoma cell line Pan02 (12). Pan02 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% glutamine, 1% 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Cellgro, Herndon, VA), and then 250,000 viable cells were injected subcutaneously into the right inner thigh of C57Bl/6 mice (cancer group) (13;14). Control animals (healthy group) were handled identically, but were injected with an identical volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Mice were then housed in a barrier facility for three weeks during which time non-metastatic tumors formed in mice injected with Pan02 cells.

Both mice with cancer and healthy mice were then made septic by induction of pneumonia via direct intratracheal injection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) (15;16). Under isoflurane anesthesia, a midline cervical incision was made, and 40μl of bacteria diluted in 0.9% NaCl (final concentration 6×106 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml) was introduced into the trachea with a 29-gauge syringe. Following incision closure, mice received a 1ml subcutaneous injection of 0.9% saline to replace insensible fluid losses. Sham mice were treated identically except they were injected with 0.9% saline. This resulted in four groups of animals - healthy sham (PBS followed by 0.9% NaCl), cancer sham (Pan02 followed by 0.9% NaCl), previously healthy septic (PBS followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa), and cancer septic (Pan02 followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa). All animals were sacrificed for tissue harvest 24 hours after intratracheal injection or followed for seven day survival. Mice had free access to food and water and were maintained on a 12 hour light-dark schedule. All studies complied with the NIH Guidelines for the Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee.

Lung histology, weights, and apoptosis

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung sections were evaluated by a pathologist blinded to sample identity to determine the severity and distribution of pneumonia using a subjective grading scale (17). Severity grades for each specimen ranged from 0 to 4 (no histopathologic abnormality to most severe pneumonia) while distribution grades ranged from 0 to 3 (no abnormality to diffuse pneumonia).

Both lungs were weighed immediately after removal from the body to obtain a “wet” weight. The lungs were then dried overnight at 80°C and reweighed and a wet to dry weight ratio was calculated. Lungs from a different group of animals were stained for active caspase 3 (as described below) to quantify pulmonary apoptosis.

Cultures and cytokine analysis

The trachea was lavaged with 1ml of sterile 0.9% NaCl to obtain bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. Whole blood was collected retro-orbitally and either processed directly for culture or centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes. Both BAL and whole blood samples were serially diluted in sterile 0.9% NaCl and plated on blood agar plates. Samples were incubated overnight at 37°C, and colony counts were determined after 24 hours of incubation. Colony counts were expressed as CFU/ml of fluid and then converted to a logarithmic scale for statistical analysis.

BAL and whole cytokine concentrations were evaluated using a cytometric bead array (BD Mouse Inflammation Kit, San Jose, CA) according to manufacturer protocol. All samples were run in duplicate.

Complete blood counts, liver function and kidney function

Blood was obtained retro-orbitally and placed in blood tubes lined with EDTA. Samples were drawn on the same animals 3 days prior to intratracheal injection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa or 0.9% NaCl and 24 hours after surgery. Complete blood counts with differentials and quantification of serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine were performed by the Division of Comparative Medicine at Washington University.

Intestinal epithelial apoptosis

Apoptotic cells in the intestinal epithelium were quantified in 100 contiguous crypt-villus units per animal by H&E-staining and active caspase-3 staining (18). Apoptotic cells were identified on H&E-stained sections by morphologic criteria where cells with characteristic nuclear condensation and fragmentation were considered to be apoptotic.

For active caspase-3 staining, sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes. Slides were placed in Antigen Decloaker (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) and heated in a pressure cooker for 45 minutes. Slides were then blocked with 20% goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-active caspase-3 (1:100; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) overnight at 4°C. Sections were incubated with goat anti-rabbit biotinylated secondary antibody (1:200; Vector Laboratories) for 30 minutes at room temperature, followed by Vectastain Elite ABC reagent (Vector Laboratories) for 30 minutes. Slides were developed with diaminobenzidine, and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Intestinal villus length and proliferation

Villus length was measured using Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD) to measure the distance in μm from the crypt neck to the villus tip in 12 well-oriented jejunal villi per animal.

Proliferation was measured in jejunal crypt sections by quantitating the number of S-phase cells in 100 contiguous crypt/villus units. S-phase cells were labeled by injecting mice intraperitoneally with 5-bromo-2′deoxyuridine (BrdU, 5mg/mL; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) 90 minutes prior to sacrifice (16). Intestinal sections were then deparaffinized, rehydrated, and incubated in 1% hydrogen peroxide for 15 minutes. Antigen retrieval was performed using Antigen Decloaker with heating in a pressure cooker for 45 minutes. Slides were blocked with Protein Block (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 10 minutes and incubated with rat monoclonal anti-BrdU (1:500; Accurate Chemical & Scientific, Westbury, NJ) overnight at 4°C. This was followed by goat anti-rat secondary antibody (1:500; Accurate Chemical & Scientific) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Sections were then placed in streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (1:500; Dako) for 60 minutes at room temperature, developed with diaminobenzidine, and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Splenocyte apoptosis

Splenocyte apoptosis was quantified via flow cytometry using commercially available antibodies against active caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology) and via the TUNEL assay (Phoenix Flow Apo-BrdU Kit, San Diego, CA) (19). T- and B- cell populations were identified using fluorescein-labeled anti-mouse CD3 (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and PE-Cy5 conjugated anti-mouse CD45R/B220 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) respectively. Flow cytometric analysis (50,000 events/sample) was performed on FACScan (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) (20).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Analysis System version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Survival studies were analyzed using the Log-Rank test. Other variables were compared between the study groups using the Two Independent Sample t test or the Wilcoxon Two Sample Test, whichever was appropriate. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Non-normally distributed data are also presented as median, followed by range. A p value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

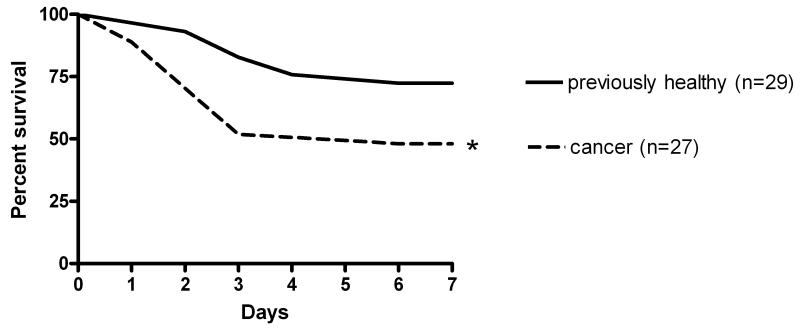

Effect of cancer on mortality from sepsis

Mice with cancer (n=27) had a higher seven-day mortality than previously healthy mice (n=29) when subjected to Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia (52% vs. 28%, p=0.04, Figure 1). Mice subjected to a sham operation with intratracheal injection of 0.9% NaCl all survived to seven days regardless of whether they had cancer or were healthy (n=10, data not shown).

Figure 1.

Effect of cancer on survival from sepsis. Mice were injected with Pan02 cells (cancer) or PBS (previously healthy). Three weeks later, all mice were given intratracheal Pseudomonas aeruginosa and then followed for 7 day survival. Cancer septic mice had significantly higher mortality than previously healthy mice subjected to the same bacterial insult (p=0.04).

Effect of cancer in sham-operated animals

Prior to evaluating potential mechanisms responsible for the mortality difference between septic mice with cancer and septic mice that were previously healthy, it was first necessary to determine what baseline differences existed in these animals independent of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. To examine this, mice with cancer given intratracheal injection of 0.9% NaCl three weeks after injection of Pan02 cells (cancer sham) were compared to mice given intratracheal injection of 0.9% NaCl three weeks after injection of PBS (healthy sham). All animals were sacrificed 24 hours after sham operation. Baseline data on all variables examined for septic animals (see below) were first evaluated in sham-operated mice. The one exception to this was that cultures were not performed in sham animals as there was no reason to assume sham animals would be actively infected.

No detectable differences were observed between cancer sham and healthy sham mice in body weights, liver function (assayed by AST, ALT levels), kidney function (assayed by BUN and creatinine levels), lung histology, wet to dry lung ratios, blood cytokine levels (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, and MCP-1), BAL cytokines (IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, and MCP-1), intestinal epithelial apoptosis, intestinal villus length, intestinal proliferation, hematocrit, white blood count, absolute neutrophil count, absolute lymphocyte count, and platelet count (data not shown). However, cancer sham mice had lower levels of T lymphocyte and B lymphocyte apoptosis compared to healthy sham mice. Cancer sham mice also had higher levels of TNF-α in BAL fluid (Table 1) compared to healthy sham mice.

Table 1. Differences in healthy sham and cancer sham mice.

| Parameter | Healthy Sham | Cancer Sham | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAL TNF-α (pg/ml) | 53±11 (n=8) 60 7-95 |

95±3 (n=8) 94 84-106 |

* 0.002 |

| CD3+ Splenocytes - TUNEL (% apoptotic cells) |

5.3±0.5 (n=12) 5.0 2.0-8,0 |

3.5±0.3 (n=10) 3.0 2.0-5.0 |

* 0.008 |

| B220+ Splenocytes - TUNEL (% apoptotic cells) |

4.7±0.4 (n=12) 4.5 2.0-7.0 |

3.0±0.3 (n=10) 3.0 2.0-5.0 |

* 0.008 |

Data are shown as:

Mean ± standard error (sample size)

Median ± minimum-maximum

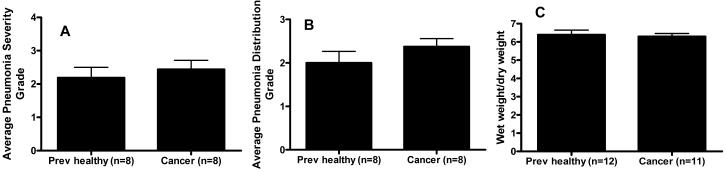

Effect of cancer on lungs of septic mice

All subsequent experiments compared mice with cancer given intratracheal injection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa three weeks after subcutaneous injection of Pan02 cells (cancer septic) to healthy mice given intratracheal injection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa three weeks after subcutaneous injection of PBS (previously healthy septic).

Histological evaluation of the lungs showed no difference in the severity or distribution of pneumonia between cancer septic and previously healthy septic mice (Figures 2A and 2B). Wet to dry lung weights were also similar in both groups (Figure 2C). BAL levels of IL-6 and IL-10 were higher in cancer septic mice than previously healthy mice while no significant differences were found between BAL levels of TNF-α, IL-12, or MCP-1 (Table 2). Of note, while there was a 2-fold variation in TNF-α levels in sham mice depending on whether an animal had cancer, TNF-α levels were greater than 70-fold higher in septic mice independent of whether they had cancer (compare Table 1 to Table 2). No differences in pulmonary apoptosis were noted between cancer septic and previously healthy septic mice (n=8/group, data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effect of cancer on pulmonary pathology following sepsis. The severity (A) and distribution (B) of pneumonia were similar following intratracheal injection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa regardless of whether an animal had cancer. Wet to dry lung ratios (C) also did not differ between the two groups of mice.

Table 2. Local and systemic cytokines in previously healthy septic and cancer septic mice.

| Bronchoalveolar lavage | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokine (pg/ml) |

Previously Healthy (n=10) |

Cancer (n=5-8) |

p-value |

| IL-12 | 2066±214 1842 1477-3760 |

2571±478 2163 1537-5759 |

ns |

| TNF-α | 4190±1582 565 103-10,000 |

6993±1554 10,000 387-10,000 |

ns |

| MCP-1 | 5292±1403 5287 5234-10,000 |

6467±1724 10,000 562-10,000 |

ns |

| IL-10 | 7±2 4 4-22 |

36±10 35 8-83 |

**p=0.003 |

| IL-6 | 1143±563 579 13-5864 |

5423±1660 4745 1361-11144 |

**p=0.008 |

| Blood | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokine (pg/ml) |

Previously Healthy (n=10) |

Cancer (n=11) |

p-value |

| IL-12 | 17±7 11 11-77.5 |

46±20 11 11-214.4 |

ns |

| TNF-α | 67±22 52 7-223 |

107±21 99 24-241 |

ns |

| MCP-1 | 1160±686 378 53-7195 |

1623±710 574 53-7930 |

ns |

| IL-10 | 2068±1516 17 17-15422 |

2539±1474 17 17-15182 |

ns |

| IL-6 | 2087±1317 479 30-13589 |

3364±1101 1322 411-10615 |

ns |

Data are shown as:

Mean ± standard error

Median ± minimum-maximum

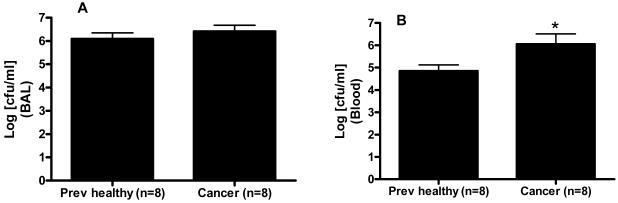

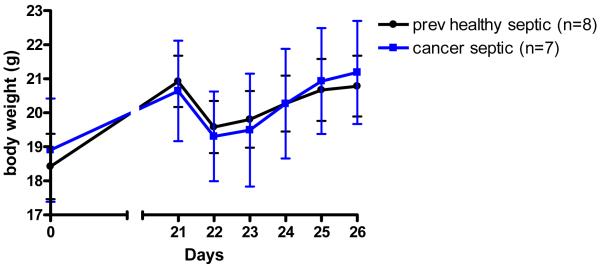

Effect of cancer on bacterial clearance, body weights, liver and kidney function in septic mice

Cultures of BAL fluid showed similar levels of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in both cancer septic and previously healthy septic mice (5.7×106 ± 1.7×106 vs. 3.3×106 ± 1.5×106 CFU/ml, Figure 3A). Despite similar levels of local infection, cancer septic mice had increased bacteremia compared to previously healthy septic mice (4.5×106 ± 1.8×106 vs. 2.5×105 ± 1.4×105 CFU/ml, Figure 3B). This was not associated with changes in systemic cytokine levels (Table 2), body weights (Figure 4), or liver or kidney function (data not shown) between the groups.

Figure 3.

Effect of cancer on bacterial burden following sepsis. BAL cultures (A) demonstrated similar levels of bacteria 24 hours following Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia regardless of whether an animal had cancer. In contrast, higher levels of bacteria were present in the bloodstream (B) of cancer septic mice than previously healthy septic mice (p=0.04).

Figure 4.

Effect of cancer on body weights before and after induction of sepsis. Animals were weighed at baseline and were then injected with either Pan02 cells or 0.9% NaCl. Three weeks later, animals were weighed again. Body weights were similar in both groups, regardless of whether they had cancer. Both cancer mice and healthy mice were then made septic via intratracheal injection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and were weighed daily for the next five days. All septic mice initially lost weight, but the presence of cancer did not affect body weight following pneumonia.

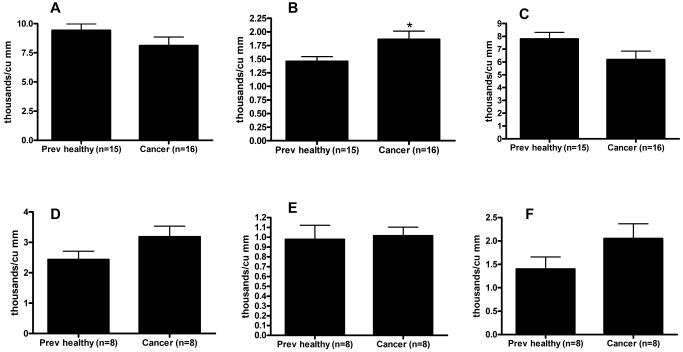

Effect of cancer on white blood cell counts in septic mice

Three days prior to intratracheal injection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, mice with cancer had a mild increase in absolute neutrophil count compared to healthy mice although their white blood count and absolute lymphocyte count were similar (Figures 5A-C). Sepsis significantly decreased white blood count, absolute neutrophil count, and absolute lymphocyte count compared to pre-operative levels (Figure 5D-F). However, these decreases were similar between cancer septic and previously healthy septic mice. Platelet count and hematocrit in septic mice were also unaffected by the presence of cancer (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Effect of cancer on blood counts before and after sepsis. White blood cell count (A) was similar in cancer mice and healthy mice three days prior to induction of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. A small increase in absolute neutrophil count (B) was seen in cancer mice (0.03) without a detectable difference in absolute lymphocyte count (C). White blood cell count, absolute neutrophil count and absolute lymphocyte count were all decreased 24 hours after the onset of sepsis (D-F); however, levels were unaffected by the presence or absence of cancer.

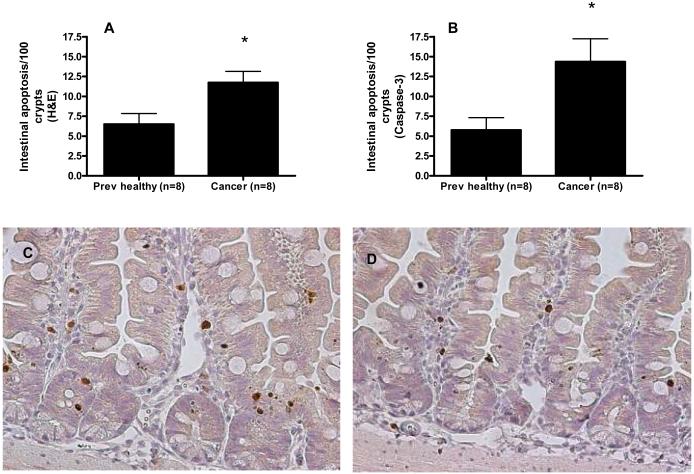

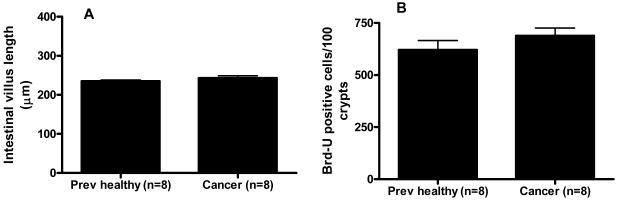

Effect of cancer on the intestinal epithelium in septic mice

Intestinal epithelial apoptosis was increased in cancer septic mice compared to previously healthy septic mice by both H&E (11.8 ± 1.4 cells/100 crypts vs. 6.5 ± 1.3 cells/100 crypts, Figure 6A) and active caspase-3 staining (14.3 ± 2.9 cells/100 crypts vs. 5.8 ± 1.6 cells/100 crypts, Figure 6B-D). In contrast, both villus length (Figure 7A) and crypt proliferation were similar between cancer septic mice and previously healthy septic mice (Figure 7B)

Figure 6.

Effect of cancer on gut epithelial apoptosis following sepsis. Gut epithelial apoptosis was increased by both H&E staining (A, p=0.02) and active caspase 3 staining (B, p=0.03) in cancer septic mice. Representative caspase 3-stained sections show increased crypt apoptosis in cancer septic mice (C) compared to previously healthy septic mice (D), magnification 200x (apoptotic cells stain brown).

Figure 7.

Effect of cancer on villus length and gut proliferation following sepsis. Both villus length (A) and number of proliferating crypt cells (B) were similar 24 hours following Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia regardless of whether an animal had cancer.

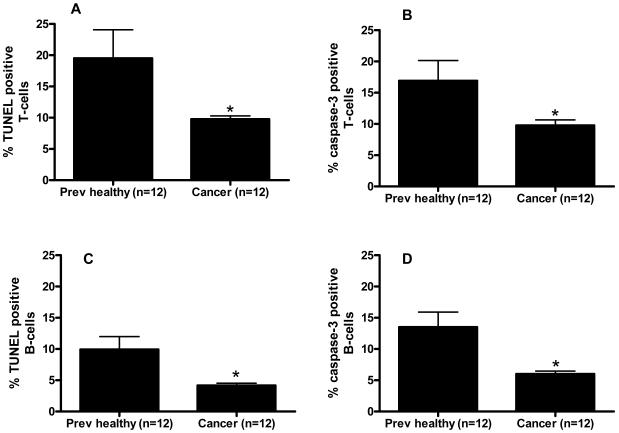

Effect of cancer on splenic apoptosis in septic mice

Cancer septic mice had decreased levels of T lymphocyte apoptosis compared to previously healthy septic mice by both the TUNEL assay (19.5 ± 4.6% positive cells vs. 9.8 ± 0.5% positive cells, Figure 8A) and active caspase-3 staining (16.9 ± 3.2% positive cells vs. 9.8 ± 0.9% positive cells, Figure 8B). A similar decrease in B lymphocyte apoptosis was noted in cancer septic mice as well by both the TUNEL assay (9.9 ± 2.1% positive cells vs. 4.2 ± 0.4% positive cells, Figure 8C) and active caspase-3 staining (13.5 ± 2.4% positive cells vs. 6.0 ± 0.5% positive cells, Figure 8D). It should be noted that although cancer decreased T and B lymphocyte apoptosis compared to previously healthy animals in both sham mice and septic mice, sepsis also independently induced a marked increase in splenocyte apoptosis regardless of whether an animal had cancer (compare Table 1 to Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Effect of cancer on splenic apoptosis following sepsis. T lymphocyte apoptosis was decreased by both the TUNEL assay (A, p=0.002) and active caspase 3 staining (B, p=0.006) in cancer septic mice. Similar results were seen for B lymphocyte apoptosis by both the TUNEL assay (C, p=0.008) and active caspase 3 staining (D, p=0.001).

DISCUSSION

Septic patients with cancer are significantly more likely to die than septic patients without cancer. The pre-existing pathology seen in a subset of hosts with cancer therefore adversely affects the outcome should the host become septic. Our mouse model of cancer and sepsis, which shows that cancer mice have significantly higher mortality than previously healthy mice given the identical septic insult, mimics the clinical scenario. The mechanisms underlying this change in mortality may be related to differences in systemic (but not local) bacterial clearance as well as gut epithelial and T and B lymphocyte apoptosis. In contrast, the differential mortality between cancer septic and previously healthy septic mice does not grossly appear to be due to differences in serum and pulmonary cytokine levels, nutritional intake, liver or kidney function, lung histology, complete blood counts and intestinal proliferation and length.

This study adds to our understanding of “two-hit” models of critical illness. There are multiple studies published recently where two physiologic insults that would not be lethal in isolation (such as peritonitis followed by development of pneumonia) combine to cause a disproportionate increase in mortality when the injuries are closely related temporally. Remick recently summarized this phenomenon by stating simply “getting sick when you are already sick is not good” (2). The model of cancer followed by sepsis presented herein can also be thought of as a “two-hit” model. However, instead of the combination of two acute insults, the first “hit” is a chronic comorbidity while the second “hit” is the septic insult. This fits well into the paradigm of “do not get sick when you are sick” (2) since becoming septic in the setting of any physiological perturbation (acute or chronic) appears to result in worse outcomes.

In order to determine what might account for the difference in mortality seen in septic mice with and without cancer, it was first necessary to determine if there were baseline differences between cancer mice and healthy mice subjected to a sham operation. The only significant differences noted were cancer sham mice had lower levels of T lymphocyte and B lymphocyte apoptosis (discussed below) as well as higher levels of TNF-α in BAL fluid. The fact that there were few detectable differences following sham operation was consistent with the fact that in the absence of sepsis, animals injected with either Pan02 cells or PBS appeared healthy (except for palpable tumors in the former) and grossly had similar levels of activity throughout the study.

Despite the relatively small differences between cancer and healthy mice following sham operation, there was a marked worsening in survival in cancer mice subjected to Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia compared to previously healthy mice subjected to the same insult. This suggests that even though cancer mice do not show large numbers of systemic differences under homeostatic conditions from healthy mice, they do not have the same ability to respond appropriately to a septic insult. This manifests itself in an inability to clear systemic infection. In the Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia model used, infection is introduced locally into the lungs but then spreads systemically into the bloodstream. The concentration of bacteria in the lungs of cancer septic and previously healthy septic mice was similar to each other as well as similar to the amount injected 24 hours earlier. In contrast, there was a nearly 20-fold difference in bacteremia in the animals (note: figure 3B has been log transformed). This implies a functional deficit in the immune system of cancer septic mice. While this was not apparent in the number or differential of white blood cells in the bloodstream, it is likely that leukocytes in cancer septic mice were not as efficient in initiating clearance of bacteria systemically, consistent with pre-existing immunosuppression caused by cancer.

Apoptosis has been theorized to play a central role in the pathophysiology of sepsis (21). Apoptosis in both the gut and in lymphocytes is elevated in animal and human autopsy studies of sepsis (22-24). Studies in which apoptosis is inhibited in either the intestine or in lymphocytes show that prevention of apoptosis in either tissue type improves survival following sepsis (15;25-28). The finding that cancer septic mice have increased intestinal epithelial apoptosis compared to previously healthy mice is consistent with past findings that the combination of an additional insult to sepsis can disproportionately increase gut apoptosis above and beyond what might be expected with either insult in isolation (29;30). Although additional studies need to be performed to verify the functional significance of this increased apoptosis, increased sepsis-induced gut epithelial apoptosis may represent a potential mechanism for increased mortality in cancer septic mice.

The T and B lymphocyte apoptosis findings under both basal conditions and septic conditions were unexpected. First, cancer mice had lower levels of apoptosis in both T and B lymphocytes in the spleen than healthy mice when subjected to sham operation. Cancer is frequently associated with alterations in apoptosis in the tumor. Although its effects on lymphocyte apoptosis distant to the tumor are not as well characterized, it was somewhat surprising that one of only a few detectable effects of Pan02-based tumors in mice given sham operation were that they prevented splenocyte apoptosis distant from the tumor. As has been demonstrated in multiple studies, sepsis induced an increase in splenic apoptosis. This increase was partially independent of cancer since both cancer septic and healthy septic mice had a 3-4 fold increase in lymphocyte apoptosis compared to cancer sham and healthy sham mice respectively. However, lymphocyte apoptosis was markedly lower in cancer septic mice than previously healthy septic mice. A large body of evidence in the literature suggests that increasing lymphocyte apoptosis is detrimental to the septic host possibly secondary to immunosuppression (31). It therefore might have been expected that cancer septic mice might have had a further increase in lymphocyte apoptosis (similar to what is seen with gut epithelial apoptosis) compared to previously healthy septic mice. Instead, the exact opposite was seen. The significance of this is unclear. Since the ratio of cancer to previously healthy lymphocyte apoptosis is similar in both sham and septic animals, it may be that lymphocyte apoptosis is functionally similar in both cancer septic and previously healthy septic mice. If this interpretation is correct, lymphocyte apoptosis is not responsible for the increased mortality in cancer septic mice. Alternatively, lymphocyte apoptosis may be beneficial in cancer septic mice since lower levels are associated with higher mortality. Theoretically, there might be a threshold of necessary lymphocyte apoptosis in these animals and levels that are too low may be as detrimental as levels that are too high. Further functional studies are necessary to investigate this unexpected finding.

This study has a number of limitations. The majority of patients with cancer have had the disease for months or years, while mice in our model have cancer for three weeks. Even though there is a 40-fold difference in lifespan between humans and mice, it is possible that the animals have not had time to develop chronic changes seen in patients with cancer. Similarly, patients develop cancer at a particular anatomic site whereas a model of injecting pancreatic cancer cells into the thigh of an animal cannot replicate “authentic” pancreatic cancer. Just as the host response can be different based upon the inciting organism in sepsis (32-34), cancers of different anatomic origin likely induce different host responses. The tumors induced by Pan02 cells are also not metastatic. While they induce clear loco-regional abnormalities (13;14), the basal systemic inflammatory milieu in metastatic disease may cause different effects in sepsis from those seen in non-metastatic disease. It is therefore unclear how generalizable our results are to sepsis in the setting of a) other non-pancreatic-based, non-metastatic cancers, b) metastatic cancer or c) comorbidities other than cancer. Next, the etiology behind differences in mortality between septic patients with cancer and previously healthy septic patients is multifactorial (6;7). The studies presented herein do not mimic patients who are increased risk for sepsis secondary to immunosuppression secondary to treatment for their cancer such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Rather, they are intended to model patients with impaired leukocyte function secondary to the underlying malignancy itself. However, we did not measure a number of elements of functional immunity at baseline which may have shown that cancer mice had detectable chronic immunosuppression prior to the onset of sepsis. Since all parameters examined except survival were studied solely at 24 hours, meaningful similarities and differences between cancer septic mice and previously healthy septic mice that occurred at other timepoints could not be observed.

Despite these limitations, we have demonstrated that cancer independently increases mortality in a murine model of sepsis. This is associated with increased bacteremia, increased intestinal epithelial apoptosis, and decreased splenic apoptosis. Further studies are needed to understand the functional significance of these differences. Performing future studies in animal models more similar to the human disease than currently used models may potentially help translation of pre-clinical findings into positive clinical trials.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Washington University Digestive Diseases Research Morphology Core. We also thank David J. Dixon, PhD for statistical review.

This work was supported by funding from National Institutes of Health (GM66202, GM072808, GM08795, GM044118, GM082008, P30 DK52574)

Reference List

- (1).Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Remick DG. Do not get sick when you are sick: the impact of comorbid conditions. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2147–2148. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000142943.99322.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).van Westerloo DJ, Schultz MJ, Bruno MJ, et al. Acute pancreatitis in mice impairs bacterial clearance from the lungs, whereas concurrent pneumonia prolongs the course of pancreatitis. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1997–2001. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000142658.22254.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Doi K, Leelahavanichkul A, Hu X, et al. Pre-existing renal disease promotes sepsis-induced acute kidney injury and worsens outcome. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1017–1025. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Williams MD, Braun LA, Cooper LM, et al. Hospitalized cancer patients with severe sepsis: analysis of incidence, mortality, and associated costs of care. Crit Care. 2004;8:R291–R298. doi: 10.1186/cc2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Danai PA, Moss M, Mannino DM, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in patients with malignancy. Chest. 2006;129:1432–1440. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.6.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Safdar A, Armstrong D. Infectious morbidity in critically ill patients with cancer. Crit Care Clin. 2001;17:531–570. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Rittirsch D, Hoesel LM, Ward PA. The disconnect between animal models of sepsis and human sepsis. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:137–143. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Poli-de-Figueiredo LF, Garrido AG, Nakagawa N, et al. Experimental models of sepsis and their clinical relevance. Shock. 2008;30:53–59. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318181a343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Fink MP. Animal models of sepsis and its complications. Kidney Int. 2008;74:991–993. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Deitch EA. Animal models of sepsis and shock: a review and lessons learned. Shock. 1998;9:1–11. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199801000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Corbett TH, Roberts BJ, Leopold WR, et al. Induction and chemotherapeutic response of two transplantable ductal adenocarcinomas of the pancreas in C57BL/6 mice. Cancer Res. 1984;44:717–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Viehl CT, Moore TT, Liyanage UK, et al. Depletion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells promotes a tumor-specific immune response in pancreas cancer-bearing mice. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1252–1258. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9015-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Liyanage UK, Goedegebuure PS, Moore, et al. Increased prevalence of regulatory T cells (T reg) is induced by pancreas adenocarcinoma. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2006;29:416–424. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000205644.43735.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Coopersmith CM, Stromberg PE, Dunne WM. Inhibition of intestinal epithelial apoptosis and survival in a murine model of pneumonia-induced sepsis. JAMA. 2002;287:1716–1721. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.13.1716. eet al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Coopersmith CM, Stromberg PE, Davis CG, et al. Sepsis from Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia decreases intestinal proliferation and induces gut epithelial cell cycle arrest. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1630–1637. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000055385.29232.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Robertson CM, Perrone EE, McConnell KW, et al. Neutrophil Depletion Causes a Fatal Defect in Murine Pulmonary Staphylococcus aureus clearance. J Surg Res. 2008;150:278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Vyas D, Robertson CM, Stromberg PE, et al. Epithelial apoptosis in mechanistically distinct methods of injury in the murine small intestine. Histol Histopathol. 2007;22:623–630. doi: 10.14670/hh-22.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Chang KC, Unsinger J, Davis CG, et al. Multiple triggers of cell death in sepsis: death receptor and mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis. FASEB J. 2007;21:708–719. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6805com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hotchkiss RS, Osmon SB, Chang KC, et al. Accelerated lymphocyte death in sepsis occurs by both the death receptor and mitochondrial pathways. J Immunol. 2005;174:5110–5118. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Hotchkiss RS, Nicholson DW. Apoptosis and caspases regulate death and inflammation in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:813–822. doi: 10.1038/nri1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Freeman BD, et al. Apoptotic cell death in patients with sepsis, shock, and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1230–1251. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Hiramatsu M, Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE, et al. Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) induces apoptosis in thymus, spleen, lung, and gut by an endotoxin and TNF-independent pathway. Shock. 1997;7:247–253. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199704000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Cobb JP, et al. Apoptosis in lymphoid and parenchymal cells during sepsis: findings in normal and T- and B-cell-deficient mice. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1298–1307. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199708000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Coopersmith CM, Chang KC, Swanson PE, et al. Overexpression of Bcl-2 in the intestinal epithelium improves survival in septic mice. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:195–201. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Knudson CM, et al. Overexpression of Bcl-2 in transgenic mice decreases apoptosis and improves survival in sepsis. J Immunol. 1999;162:4148–4156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Schwulst SJ, Muenzer JT, Peck-Palmer OM, et al. Bim siRNA decreases lymphocyte apoptosis and improves survival in sepsis. Shock. 2008;30:127–134. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318162cf17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Bommhardt U, Chang KC, Swanson PE. Akt decreases lymphocyte apoptosis and improves survival in sepsis. J Immunol. 2004;172:7583–7591. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7583. eet al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Turnbull IR, Buchman TG, Javadi P, et al. Age disproportionately increases sepsis-induced apoptosis in the spleen and gut epithelium. Shock. 2004;22:364–368. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000142552.77473.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Javadi P, Buchman TG, Stromberg PE, et al. High-dose exogenous iron following cecal ligation and puncture increases mortality rate in mice and is associated with an increase in gut epithelial and splenic apoptosis. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1178–1185. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000124878.02614.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Hotchkiss RS, Chang KC, Grayson MH. Adoptive transfer of apoptotic splenocytes worsens survival, whereas adoptive transfer of necrotic splenocytes improves survival in sepsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 100:6724–6729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031788100. eet al. 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Yu SL, Chen HW, Yang PC, et al. Differential gene expression in gram-negative and gram-positive sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:1135–1143. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200211-1278OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Ramilo O, Allman W, Chung W, et al. Gene expression patterns in blood leukocytes discriminate patients with acute infections. Blood. 2007;109:2066–2077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-002477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Feezor RJ, Oberholzer C, Baker HV, et al. Molecular characterization of the acute inflammatory response to infections with gram-negative versus gram-positive bacteria. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5803–5813. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5803-5813.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]