Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated endogenously or from exogenous sources produce mutagenic DNA lesions. If not repaired, these lesions could lead to genomic instability and, potentially, to cancer development. NEIL2 (EC 4.2.99.18), a mammalian base excision repair (BER) protein and ortholog of the bacterial Fpg/Nei, excises oxidized DNA lesions from bubble or single-stranded structures, suggesting its involvement in transcription-coupled DNA repair. Perturbation in NEIL2 expression may, therefore, significantly impact BER capacity and promote genomic instability. To characterize the genetic and environmental factors regulating NEIL2 gene expression, we mapped the human NEIL2 transcriptional start site and partially characterized the promoter region of the gene using a luciferase reporter assay. We identified a strong positive regulatory region from nucleotide −206 to +90 and found that expression from this region was contingent on its being isolated from an adjacent strong negative regulatory region located downstream (+49 to +710 bp), suggesting that NEIL2 transcription is influenced by both these regions. We also found that oxidative stress, induced by glucose oxidase treatment, reduced the positive regulatory region expression levels, suggesting that ROS may play a significant role in regulating NEIL2 transcription. In an initial attempt to characterize the underlying mechanisms, we used in silico analysis to identify putative cis-acting binding sites for ROS-responsive transcription factors within this region and then used site-directed mutagenesis to investigate their role. A single-base change in the region encompassing nucleotides −206 to +90 abolished the effect of oxidative stress that was observed in the absence of the mutation. Our study is the first to provide an initial partial characterization of the NEIL2 promoter and opens the door for future research aimed at understanding the role of genetic and environmental factors in regulating NEIL2 expression.

Introduction

The human genome is constantly exposed to reactive oxygen species (ROS) which induce oxidative DNA lesions that may lead to mutations, genomic instability and, potentially, to the development of cancer (1,2). The DNA base excision repair (BER) pathway includes several proteins that function in a stepwise manner to repair these DNA lesions (2,3). The importance of maintaining the integrity of this pathway has been demonstrated by many epidemiological studies. For example, changes in the activity or protein structure of several BER enzymes, including 8-oxoguanine-DNA glycosylase (OGG1) and apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease, have been associated with elevated cancer risk (4). In addition, polymorphisms of the XRCC1 and ADPRT genes, which code for other important BER proteins, were associated with increased genetic damage and increased cancer risk (1,5–7).

The first step in the BER pathway is the recognition and removal of the damaged DNA base, usually by a glycosylase (3). In mammals, several BER glycosylases have been identified, including the monofunctional glycosylases endonuclease III homolog 1 and OGG1, and the newly discovered NEIL1 and NEIL2 proteins. The latter two belong to the Fpg/Nei family of BER enzymes (8–12). Recent studies have shown unique important properties of NEIL2 that set it apart from other BER glycosylases. For example, NEIL2 is active throughout the cell cycle, but its activity is enhanced in the presence of oxidative stress, further emphasizing its potential importance in removing oxidative DNA damage (8–14). Furthermore, there is a growing evidence suggesting that NEIL2 is involved in transcription-coupled DNA repair, which may have important health implications since the repair of oxidized bases from active sequences during transcription is critical to normal mRNA processing and stability (15). As such, NEIL2 may play a substantial role in maintaining genomic stability not only in highly proliferating cells but also in non-dividing cells that remain transcriptionally active, such as nerve cells (16). Therefore, factors affecting the level of expression of NEIL2 protein, or those that affect its structure and function, may lead to diverse and serious health consequences.

With the long-term goal of characterizing the genetic and the environmental factors involved in the regulation of NEIL2 expression, in this study, we partially characterized the promoter of the NEIL2 gene after mapping its transcriptional start site. We then identified a positive regulatory region within the NEIL2 promoter that was responsive to oxidative stress.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

MRC-5 cells (normal embryonic human lung fibroblasts) were acquired from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (lot no. 3929228; ATCC, Manassas, VA) and were cultured in flasks containing Eagle's minimal essential medium with Earle's basal salts and 2 mM L-glutamine supplemented with 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 1.5 g/litre sodium bicarbonate, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 10% foetal bovine serum. The cultures were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Twenty-four hours prior to transfection, cells were harvested from the flasks, counted and seeded in 6-well plates at a concentration of 3.5 × 105 cells per well.

Mapping of the NEIL2 transcriptional start site and in silico analysis for the identification of putative cis-acting binding sites in the promoter region

The FirstChoice RLM-RACE primer extension kit (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX) was used to identify the transcriptional start site. Briefly, total RNA was isolated from MRC-5 cells and a 10 μg of the total RNA was treated with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase and then treated with tobacco acid pyrophosphatase to specifically modify the full-length mRNA for adapter ligation. The 5′ RACE adapter (included with the primer extension kit) was ligated to the 5′ end of the full-length mRNA, which provided a template for primer extension during the subsequent reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifications. In the first reaction, the 5′ RACE outer primer (included with the kit) was used in combination with the NEIL2 gene-specific primers (RACE1, 5′-TCTTCCGAGTGCCCGAGGTG-3′ and RACE2, 5′-GGGGTTGTCTCCGCCGTTC-3′) that were designed based on GenBank mRNA (NM_145043) sequence data. A second PCR reaction was used to amplify the region using the same gene-specific primers and the 5′ RACE inner primer (included with the extension kit). The products of this latter reaction were sequence verified using the ABI Prism 3100 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and BLASTn software (National Center for Biotechnology Information).

Following the identification of the transcriptional start site, the transcription element search system (TESS, University of Pennsylvania), which allows the in silico identification of functional cis-acting binding sites within the DNA strand (17), was subsequently used to search for putative cis elements located within the proximity of the transcriptional start site. The TESS analysis was performed using the default basic and expert parameters. An initial search for all transcription factors was conducted, which was later restricted to ROS-responsive factors.

Cloning of the NEIL2 5′ upstream region into luciferase reporter vectors

The 5′ gene region of NEIL2 was isolated from genomic DNA through PCR. We used primers that were specifically designed to amplify the regions of interest (Table I). The resulting fragments were then cloned into the pCR2.1 vector, using the TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) and then sub-cloned into the KpnI/EcoRI restriction sites in the promoter-less luciferase expression plasmid, pGL3-Basic (Promega, Inc., Madison, WI) to create the three plasmids pSTEP1, pSTEP2 and p1200. The construct pSTEP3 was created by cloning a 661-bp fragment of the region from +49 to +710 into the BglII site of the pGL3-Basic vector (see Figure 1).

Table I.

Primer sequences for luciferase constructs

| Luciferase construct | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

| pSTEP1 | 5′-GAGCTGGTGGGCTGGGCTTGTTT-3′ | (5′-CACATTCAATAACGCGCATC-3′ |

| pSTEP2 | 5′-TAGCCGGGCGCCAGTAATCC-3′ | 5′-CACATTCAATAACGCGCATC-3′ |

| pP1200 | 5′-GAGCTGGTGGGCTGGGCTTGTTT-3′ | 5′-GAAGCTTTCCCCTCCCGACTTCTC-3′ |

| p1200A | 5′-GAGCTGGTGGGCTGGGCTTGTTT-3′ | 5′-CTTGTCTCAAGGACACAGTT-3′ |

| p1200B | 5′-CACCCATTGACTTTTCCC-3′ | 5′-TGTAGGTGGAGGCTGCGG-3′ |

| p1200C | 5′-TTTCCAGGGAATGAGCCCT-3′ | 5′-GAAGCTTTCCCCTCCCGACTTCTC-3′ |

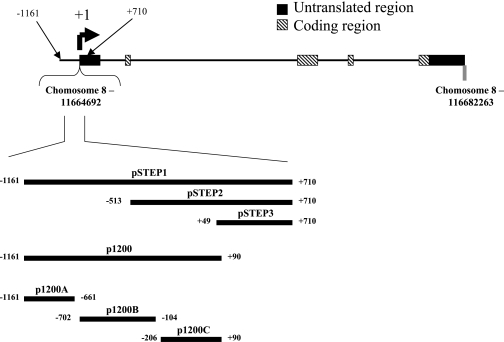

Fig. 1.

Schematic presentation of the NEIL2 gene and the relative locations of the promoter fragments isolated, cloned and sub-cloned into luciferase reporter vectors. The identified transcriptional start site is designated as +1.

Sub-clone constructs of the p1200 and pSTEP3 fragments

In addition to the constructs described above, three fragments were amplified from the p1200 construct (see Figure 1) using the primers shown in Table I. The fragment encompassing the 5′ region of the p1200 insert (from −1161 to −661) was used to create the p1200A construct. The central fragment (from −702 to −104) was used to create the p1200B construct. The 3′ region (from −206 to +90) was used to create the p1200C construct.

To evaluate the characteristics of the pSTEP3 fragment, we cloned this fragment into a pGL-control vector containing the strong, ubiquitous simian virus 40 promoter (pSV40). The pSV40-STEP3 construct was created by ligating the BglII fragment. The integrity of the cloned fragments was verified by direct sequencing. Plasmid DNA used for transfections was isolated using the Qiagen EndoFree Maxi prep (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). The stock DNA extract was diluted in endotoxin-free water to a final concentration of 1 μg/μl prior to transfection. In order to ensure plasmid integrity, all plasmid preparations were performed 3 days prior to transfection.

Site-directed mutagenesis and luciferase expression constructs

Using the p1200C as a template, we used the Quickchange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, Inc., La Jolla, CA) to introduce a single-base change at a location 104 bp 5′ of the transcriptional start site (denoted as −104 G to C). The PCR primer set 5′-GCCTCCACCTACAGGCGCGTCCCCTAAGGGG-3′ and 5′-CCCCTTAGGGGACGCGCCTGTAGGTGGAGGC-3′ were used in this process. This single-base change (bold and underlined) was predicted by TESS analysis to abolish the binding sites for the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB) and Sp-1 transcription factors (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

The DNA sequence, encompassing the pSTEP1 fragment, that includes the NEIL2 gene sequence flanking 5′ upstream and 3′ downstream of the identified transcriptional start site (+1). Putative consensus sequences for binding to regulatory factors are activator protein 1 (AP-1) (highlighted), CREB (italicized), NFκB (underlined) and PEA3 (bold and italicized). Mutation of a putative NFκB/Sp-1 site denoted in rectangle.

Transient transfection of MRC-5 cells with NEIL2 promoter constructs and luciferase assay

MRC-5 cells were transfected with the constructs described above for 4.5 h in a mixture of 1.0 μg DNA per well at a Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Inc.) concentration of 6 μg of Lipofectamine per microgram plasmid DNA. After transfection, cells were allowed to recover for 48 h and then were harvested in 1× Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega, Inc.). Luciferase reporter gene expression was detected using the Luciferase Detection Kit (Promega, Inc.). Briefly, cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and incubated in 200 μl of cell lysis buffer. Luciferase activity was measured according to the manufacturer's instructions and detected on a GENios Pro Microplate Reader (Tecan, Inc., Durham, NC). The total cellular protein concentration was determined using a Bradford-based assay from Bio Rad (Bio Rad Protein Assay, Bio Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The total recoverable cellular protein concentration was determined by calibration relative to a standard curve generated using known concentrations of aqueous bovine serum albumin between 0 and 24 mg/ml. Transfection efficiency was tested using co-transfection with Renilla luciferase (control reporter) and detected using the Dual Luciferase Reporter System (Promega, Inc.). Luminescence was measured in relative light units per microlitre. The relative luciferase activity in each sample was normalized to the total concentration of protein. Each experiment was repeated at least five times. Although extreme care was used to achieve optimal and reproducible experimental conditions, we found that luciferase expression varied from experiment to experiment based on cell passage number. Each experiment was therefore normalized to its own internal control and was performed on cells from the same passage.

Response of the p1200C construct to oxidative stress

MRC-5 cells were transfected with the p1200C construct (the fragment from −206 to +90 bp) and treated with the cellular oxidant glucose oxidase (GO) in presence of flavin adenine dinucleotide acquired from Roche Applied Science, Inc. (Basel, Switzerland) at a final concentration of 100 ng/ml. GO is a strong cellular hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) generator that creates an environment conducive to dynamic oxidative DNA damage, and at this concentration, it was shown to increase intracellular ROS in cultured cells by 2.4-fold after 1 h of treatment (16). Prior to treatment, cultures were allowed to recover for 24 h (after transfection) in fresh medium. Cells were treated with GO and luciferase expression levels determined at 1, 6 and 12 h after treatment. The experimental conditions used did not affect cell viability, as determined by trypan blue exclusion.

Statistical analysis

The Student's t-test and analysis of variance were used, when appropriate, to compare the means between treatment groups. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using NCSS 2004 (Kaysville, UT).

Results

Mapping of the NEIL2 transcriptional start site and identification of cis elements in the NEIL2 promoter region

Our results indicate that the guanine residue at location 11664692G on chromosome 8 is the transcriptional start site (designated as +1 in Figures 1 and 2). Using the TESS software (17), we were also able to identify, in silico, several potential binding sites for transcription factors in this region, including those for NFκB, a cAMP response element-binding protein and an activator protein 1 site (a heterodimer formed from C-jun and C-Fos) (Figure 2). The analysis of the sequence surrounding the transcriptional start site suggests that the NEIL2 gene is driven by a GC-rich, TATA-less promoter.

Partial characterization of the NEIL2 promoter region

To characterize the promoter of the NEIL2 gene, we isolated regions of DNA surrounding the identified transcriptional start site. These isolated DNA fragments were then cloned into luciferase reporter vectors and subsequently tested for their ability to drive luciferase expression in vitro. Relative luciferase expression from each construct was measured and then normalized to the co-transfected Renilla plasmid. As shown in Figure 3A, the largest construct of the NEIL2 promoter fragment pSTEP1 (the fragment from −1161 to +710 bp) did not drive expression. We therefore designed the p1200 construct (from −1161 to +90 bp), which contained the first 1251 of the −1161 to +710-bp fragment, including the transcription start site. This was equivalent to deleting the pSTEP3 fragment (+49 to +710 bp) located in the −1161 to +710 fragment. The p1200 construct showed a 5-fold higher expression level compared to the pSTEP1, suggesting that it contained positive regulatory elements (Figure 3B). Furthermore, because the −1161 to +90 fragment did not contain the +49 to +710 fragment, we hypothesized that the +49 to +710 region contained negative regulatory elements that repressed the induction of NEIL2 expression observed with the pSTEP1 and pSTEP2 constructs.

Fig. 3.

(A) Luciferase constructs containing DNA fragments of the 5′-regulatory region that were cloned upstream of the luciferase-coding sequence; (B) promoter activity (determined as described in Materials and methods). *P < 0.05.

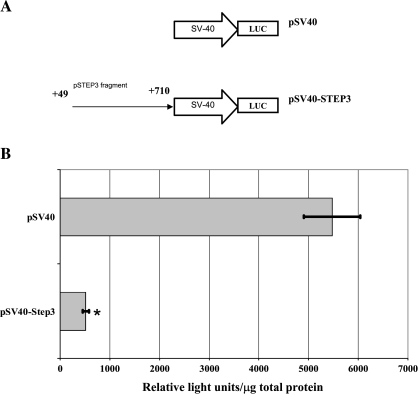

To characterize the repressive characteristics of the +49 to +710 fragment (pSTEP3), we cloned it into a pGL control vector containing the SV40 promoter (Figure 4A). Inserting the +49 to +710 fragment proximal to the SV40 promoter (pSV40-STEP3) resulted in a 91% decrease in SV40-driven luciferase expression (Figure 4B).

Fig. 4.

(A) Luciferase constructs containing the pSTEP3 DNA fragment inserted 5′ of a SV40 promoter; (B) promoter activity relative to a pSV40 control vector is shown in relative light units (RLUs) per millilitre, normalized to total protein in the sample. *P < 0.05.

We further characterized key regions responsible for positive regulation of the NEIL2 gene by sub-cloning segments of the −1161 to +90 fragment (p1200) into three constructs (p1200A, p1200B and p1200C; Figure 5A). While the relative promoter activity of the p1200C construct (containing the fragment from −206 to +90 bp and the transcriptional start site) was comparable to the relative promoter activity of the −1161 to +90 fragment (p1200), the relative promoter activity of the p1200A construct (the fragment from −1161 to −661 bp) was 5-fold lower than that of the p1200C (P < 0.01). In addition, the promoter activity of the fragment from −702 to −104 bp (p1200B) was 3-fold lower than that of p1200C (P < 0.01; Figure 5B).

Fig. 5.

(A) Luciferase sub-clone constructs containing fragments (A, B and C) of the p1200 DNA fragment inserted upstream of luciferase-coding sequence; (B) promoter activity (determined as described under Materials and methods). *P < 0.05.

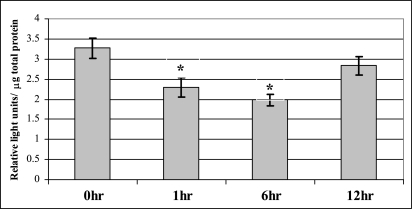

Response of the p1200C construct (−206 to +90 fragment) to oxidative stress

Because the fragment from −206 to +90 bp (p1200C) drove the highest level of luciferase expression, we examined the response of this fragment to oxidative stress induced by GO. The −206 to +90 fragment responded dramatically to GO treatment, with a significant transient decrease in luciferase expression at 1 h that persisted for up to 6 h after treatment (40% decrease; P < 0.01). At 12 h, expression completely recovered to the same level as the untreated (Figure 6).

Fig. 6.

Luciferase reporter activity in cells transfected with the p1200C constructs and then treated with GO (100 ng/ml) for 1, 6 and 12 h. Comparisons are between GO treated at 1, 6 and 12 h versus untreated. *P < 0.05.

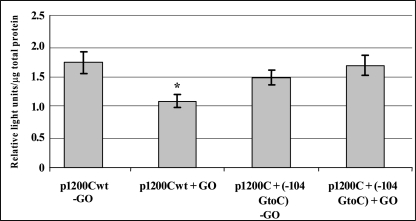

In silico analysis of the p1200C plasmid indicated the presence of a genomic sequence of a potential putative NFκB/Sp-1 site. Because both NFκB and Sp-1 transcriptional regulating proteins are known to be activated by ROS, perturbation of this site might affect the response to oxidative stress (18–20). Our data indicate that cells transfected with the p1200C plasmid containing a −104 G to C mutation within the sequence of the potential NFκB/Sp-1-binding site elicited a different response compared to cells transfected with the wild-type p1200C plasmid. In cells transfected with the mutated plasmid, there was no change in expression level observed following exposure to GO for 1 h (Figure 7).

Fig. 7.

Promoter activity for p1200C wild type and p1200C + mutation in NFκB/Sp-1 site (104 G to C) with and without 1 h GO treatments (determined as described in Materials and methods). *P < 0.05.

Discussion

This study is the first to provide an initial partial characterization of the NEIL2 promoter and the first to identify the transcriptional start site and important genetic factors regulating NEIL2 expression. Evaluation of the expression activities of several fragments of the promoter region revealed that the 1871-bp fragment from −1161 to +710 (pSTEP1 construct) did not drive expression in MRC-5 cells, even though it contained the transcriptional start site as well as several putative transcriptional element-binding sites. These findings suggest that this fragment may contain negative regulatory regions that suppress expression. In fact, sub-cloning of this fragment demonstrated that it contained both positive and negative regulatory regions.

The results from our sub-cloning studies indicate that the +49 to +710 fragment did not drive luciferase expression in the pSTEP3 construct. A possible explanation to this finding could be that this fragment lacks the transcriptional start site. However, when this fragment was placed in front of the full-length SV40 promoter, which contained a start site, it reduced the SV40-driven luciferase expression by 91%, strongly suggesting that it contains repression elements that may negatively impact NEIL2 gene expression. Further support to this conclusion stems from the fact that this fragment was common to both pSTEP1 and pSTEP2, both of which contained the start site, but still did not drive luciferase expression. In addition, the SV40 promoter is commonly used in the pGL3 control vector as a positive transfection control because it promotes strong reporter gene expression in various mammalian cell types (21). As such, repressing its expression would, presumably, require robust repression elements. Our results, therefore, strongly suggest that this region of the NEIL2 promoter retains strong repression motifs that regulate basal NEIL2 gene expression.

Our study showed that the fragment from −1161 to +90 bp (p1200) drove substantial luciferase expression, suggesting that it is likely to contain positive regulatory elements. Our in silico TESS analysis suggested the presence of putative cis-binding sites for various transcription factors within the −1161 to +90 fragment, particularly within the −206 to +90 region. The results from the experiments in which we used the three constructs (p1200A, p1200B and p1200C), each containing different regions of the −1161 to +90 insert (Figure 1), clearly indicate that the −206 to +90 fragment contained essential positive regulatory elements. Our results indicate that an in-depth examination of this region is needed to identify the specific elements responsible for driving expression from this construct.

Because the NEIL2 protein is involved in the repair of oxidative DNA damage, we hypothesized that NEIL2 gene expression would be responsive to ROS. Our results indicate that GO treatment of MRC-5 cells transiently transfected with the p1200C plasmid (the −206 to +90 fragment) was associated with down-regulation of expression. Transcriptional response to ROS is diverse and may include induction or repression of gene expression (20,22,23). For example, in some studies, ROS were shown to act as a cellular messenger that activates the transcription of some DNA repair genes (24), while in other studies ROS had no effect on expression levels of other DNA repair genes, including XRCC1, XRCC5 and ERCC5 (25). Consistent with our findings, it has been also shown that ROS can down-regulate gene transcription. For example, ROS have been shown to down-regulate the transcription of OGG1 (another BER protein), cytokines, tumor necrosis factor alpha as well as pro-inflammatory genes (20,22,23). Several motifs in the NEIL2 promoter that bind transcription factors could negatively be impacted in presence of oxidative stress (20). For example, the transactivation by the Sp-1 factor, the E26 transformation-specific (ETS) transcription factor and the upstream stimulatory factor (USF) are known to be inhibited in the presence of ROS (20). It is interesting to note that our TESS in silico analysis suggests the presence of putative USF-binding sites and several putative SP-1-binding sites in the −206 to +90 fragment (p1200C) located upstream but close to the transcriptional start site. A plausible explanation to our findings with the p1200C construct could, therefore, be that the oxidative conditions induced by GO resulted in inhibition of binding of transcriptional proteins, such as Sp-1, USF or ETS, to their respective sites on the DNA in a similar manner as discussed above, which resulted in reduced luciferase expression in cells transfected with the p1200C construct.

The results from our in silico analysis also revealed the potential presence of a dual motif for both a Sp-1 and NFκB-binding protein in the −206 to +90 fragment (Figure 2). Both of these transcription factors have been well characterized with respect to their role in regulating gene expression in cells under oxidative stress. Thus, our findings suggest that there could be at least two ROS-responsive transcription factors competing for binding at this site (19). The results from our site-directed mutagenesis studies of this region indicate that introducing a mutation at this site changes the response of this regulatory region to oxidative stress. While additional studies are still needed to identify the specific factors involved in this response, our studies indicate that sequence variations in the NEIL2 promoter region can significantly alter the transcriptional response to oxidative stress.

In conclusion, our study is the first to provide an initial partial characterization of the NEIL2 promoter and opens the door for future research aimed at understanding the role of genetic and environmental factors in regulating NEIL2 expression. Our study also identifies important gaps in knowledge that need to be addressed by future studies. An important issue is the biological effect of down-regulation of NEIL2 in response to oxidative stress, given the possible importance of this protein in transcription-coupled DNA repair. In rapidly proliferating tissues, reduced NEIL2 transcription may lead to increased oxidative stress and genomic instability. In non-dividing, but transcriptionally active cells, this may lead to a mutagenic cell state.

Funding

National Institutes of Environmental Health Science Center award (ES06676, CA98549) by a John Sealy Memorial Endowment Grant; pre-doctoral fellowships from National Institutes of Environmental Health Science (T32-07454) to C.J.K., C.M.R., C.E.H; Institute for Translational Sciences–Clinical Research Center at The University of Texas Medical Branch; National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health (1UL1RR029876-01).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Marinel M. Ammenheuser for her critical review of the manuscript. Conflict of interest statement: None declared.

References

- 1.Nohl H, Kozlov AV, Gille L, Staniek K. Cell respiration and formation of reactive oxygen species: facts and artefacts. Biochem. Soc., Trans. 2003;31:1308–1311. doi: 10.1042/bst0311308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fortini P, Pascucci B, Parlanti E, D'Errico M, Simonelli V, Dogliotti E. The base excision repair: mechanisms and its relevance for cancer susceptibility. Biochimie. 2003;8:1053–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiederhold L, Leppard JB, Kedar P, et al. AP endonuclease-independent DNA base excision repair in human cells. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zienolddiny S, Campa D, Lind H, Ryberg D, Skaug V, Stangeland L, Phillips DH, Canzian F, Haugen A. Polymorphisms of DNA repair genes and risk of non-small cell lung cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:560–567. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdel-Rahman SZ, El-Zein RA. The 399Gln polymorphism in the DNA repair gene XRCC1 modulates the genotoxic response induced in human lymphocytes by the tobacco-specific nitrosamine NNK. Cancer Lett. 2000;159:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00532-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdel-Rahman SZ, Soliman AS, Bondy ML, Omar S, El-Badawy SA, Khaled HM, Seifeldin IA, Levin B. Inheritance of the 194Trp and the 399Gln variant alleles of the DNA repair gene XRCC1 are associated with increased risk of early-onset colorectal carcinoma in Egypt. Cancer Lett. 2000;159:79–86. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00537-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Miao X, Liang G, et al. Polymorphisms in DNA base excision repair genes ADPRT and XRCC1 and risk of lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:722–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bandaru V, Sunkara S, Wallace SS, Bond JP. A novel human DNA glycosylase that removes oxidative DNA damage and is homologous to Escherichia coli endonuclease VIII. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2002;1:517–529. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hazra TK, Kow YW, Hatahet Z, Imhoff B, Boldogh I, Mokkapati SK, Mitra S, Izumi T. Identification and characterization of a novel human DNA glycosylase for repair of cytosine-derived lesions. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:30417–30420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200355200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hazra TK, Izumi T, Kow YW, Mitra S. The discovery of a new family of mammalian enzymes for repair of oxidatively damaged DNA, and its physiological implications. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:155–157. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morland I, Rolseth V, Luna L, Rognes T, Bjoras M, Seeberg E. Human DNA glycosylases of the bacterial Fpg/MutM superfamily: an alternative pathway for the repair of 8-oxoguanine and other oxidation products in DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4926–4936. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takao M, Kanno S, Kobayashi K, Zhang QM, Yonei S, van der Horst GT, Yasui A. A back-up glycosylase in Nth1 knock-out mice is a functional Nei (endonuclease VIII) homologue. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:42205–42213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206884200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das A, Wiederhold L, Leppard JB, et al. NEIL2-initiated, APE-independent repair of oxidized bases in DNA: evidence for a repair complex in human cells. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2006;5:1439–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Englander EW, Ma H. Differential modulation of base excision repair activities during brain ontogeny: implications for repair of transcribed DNA. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2006;127:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dou H, Mitra S, Hazra TK. Repair of oxidized bases in DNA bubble structures by human DNA glycosylases NEIL1 and NEIL2. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:49679–49684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson DM, III, Bohr VA. The mechanics of base excision repair, and its relationship to aging and disease. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2007;6:544–559. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schug J, Overton GC. Modeling transcription factor binding sites with Gibbs Sampling and Minimum Description Length encoding. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 1997;5:268–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Cooke MS. Oxidative DNA damage and disease: induction, repair and significance. Mutat. Res. 2004;567:1–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller K, Gawlik I. Effects of reactive oxygen species on the biosynthesis of 12 (S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid in mouse epidermal homogenate. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1997;23:321–330. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morel Y, Barouki R. Repression of gene expression by oxidative stress. Biochem. J. 1999;3:481–496. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wildeman AG. Regulation of SV40 early gene expression. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1988;66:567–577. doi: 10.1139/o88-067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun Y, Oberley LW. Redox regulation of transcriptional activators. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996;21:335–348. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathy-Hartert M, Martin G, Devel P, by-Dupont G, Pujol JP, Reginster JY, Henrotin Y. Reactive oxygen species downregulate the expression of pro-inflammatory genes by human chondrocytes. Inflamm. Res. 2003;52:111–118. doi: 10.1007/s000110300023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maunders H, Patwardhan S, Phillips J, Clack A, Richter A. Human bronchial epithelial cell transcriptome: gene expression changes following acute exposure to whole cigarette smoke in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2007;292:L1248–L1256. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00290.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Leeuwen DM, Gottschalk RW, van Herwijnen MH, Moonen EJ, Kleinjans JC, van Delft JH. Differential gene expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells induced by cigarette smoke and its constituents. Toxicol. Sci. 2005;86:200–210. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]