Abstract

Epigenetics is a rapidly growing field and holds great promise for a range of human diseases, including brain disorders such as Rett syndrome, anxiety and depressive disorders, schizophrenia, Alzheimer disease and Huntington disease. This review is concerned with the pharmacology of epigenetics to treat disorders of the epigenome whether induced developmentally or manifested/acquired later in life. In particular, we will focus on brain disorders and their treatment by drugs that modify the epigenome. While the use of DNA methyl transferase inhibitors and histone deacetylase inhibitors in in vitro and in vivo models have demonstrated improvements in disease-related deficits, clinical trials in humans have been less promising. We will address recent advances in our understanding of the complexity of the epigenome with its many molecular players, and discuss evidence for a compromised epigenome in the context of an ageing or diseased brain. We will also draw on examples of species differences that may exist between humans and model systems, emphasizing the need for more robust pre-clinical testing. Finally, we will discuss fundamental issues to be considered in study design when targeting the epigenome.

Keywords: epigenetics, epigenome, brain disorders, DNA methylation, histone modifications, histone acetylation, histone deacetylase inhibitors

The complexity of the epigenome

Epigenetics refers to modifications that result in heritable changes in gene expression that are independent of changes in the genetic sequence (Probst et al., 2009). This includes DNA methylation, histone modifications and more recently RNA interference – particularly through non-coding microRNA (miRNA) (Volpe et al., 2002). Epigenetics was originally thought to have a role predominantly in development and cell differentiation, enabling cells with identical genomes to take on distinct phenotypes based on epigenetic programming (Holliday, 1990). It is now known that these modifications have far more diverse roles in ‘genomic regulation’, are reversible and can be manipulated by environmental cues and therapeutics. Of particular interest in this review is the role of epigenetic defects or ‘epi-mutations’, which may dictate susceptibility to or be involved in the pathogenesis of diseases in the human brain. This review will not cover the extensive work being carried out in the field of cancer biology related to epigenetics as this area has already been thoroughly reviewed in excellent previous articles (Kim et al., 2006; Rasheed et al., 2007; Jain et al., 2009).

DNA methylation

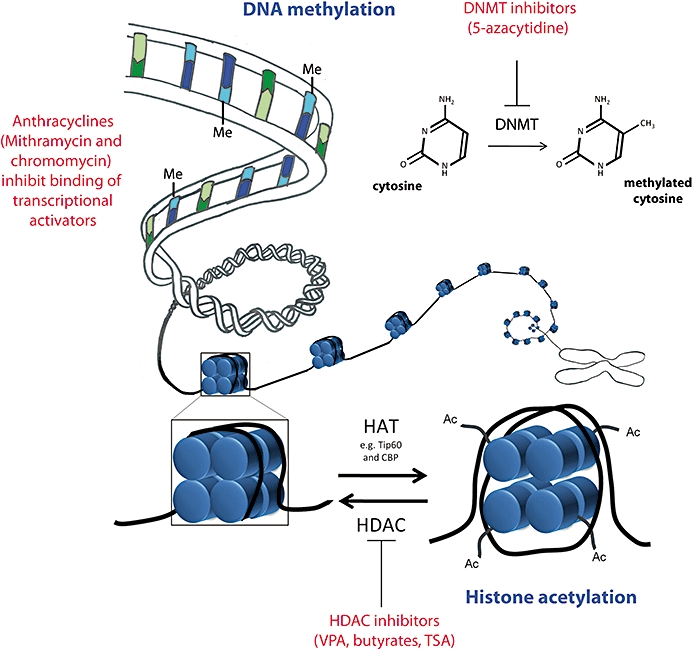

DNA methylation and histone modifications are two major forms of epigenetic modifications (see Figure 1). DNA methylation occurs at the five carbon positions of cytosine residues that are often found in CpG-rich regions of the genome (Saxonov et al., 2006). CpG dinucleotides occur at a considerably low frequency throughout the human genome, but are concentrated in regions termed CpG islands found in promoter regions of some genes. A CpG island is defined as a 200 bp region of DNA where the GC content is greater than 60% (Jones and Takai, 2001; McKay et al., 2004). DNA methyl transferases (DNMTs) catalyse the transfer of methyl groups from S-adenosyl-methionine to cytosine residues (Wu and Santi, 1985; 1987; Bestor and Verdine, 1994). Folate and vitamin B12 are essential cofactors for the methylation cycle (Reynolds, 2006). Methylated cytosine residues interfere with the binding of transcription factors and transcription machinery, and are usually associated with silencing gene expression (Razin and Riggs, 1980). For some time, it was believed that DNA methylation is an irreversible modification; however, akin to excision repair processes, it has been proposed that repair enzymes like glycolases can replace methylated cytosines with unmethylated cytosines (Jost et al., 1995). It has been shown that methylated cytosine residues are recognized by methyl DNA binding complexes consisting of methyl CpG binding protein 1 and 2 (MeCP1, MeCP2), also known as methyl CpG binding domain proteins 1–3 (MBD1–3), which further recruit co-repressor complexes and histone deacetylase (HDAC) enzymes (Eden et al., 1998; Jones et al., 1998; Nan et al., 1998; Fuks et al., 2000; Rountree et al., 2000) (see below). This particular interaction between methylated CpG islands and co-repressor (and/or co-activator) complexes which contain histone-modifying enzymes such as HDACs demonstrates that cross talk occurs between DNA methylation and histone modifications (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Drugs that can alter epigenetic modifications. DNA methyl transferases (DNMTs) catalyse the transfer of methyl groups from S-adenosyl methionine to cytosine residues within CpG-rich regions of the genome. DNA methylation generally leads to transcriptional silencing. 5-Aza, a DNMT inhibitor can prevent DNA methylation and potentially enable the reactivation of aberrantly silenced genes in the context of disease. Anthracyclines, chromomycin and mithramycin can inhibit transcriptional activators such as Sp1 and Sp2 by competing for their cognate methyl-cytosine binding sites and thus preventing the activation and up-regulation of genes controlled by Sp1/Sp2. The highly regulated interplay between the activity of histone acetyl transferases (which increase acetylation) and histone deacetylases (which decrease acetylation) controls histone acetylation homeostasis. Histone deacetylation closes up the chromatin structure, while histone acetylation generally makes chromatin more accessible for gene activation. Histone deacetylase inhibitors, such as valproic acid, trichostatin A and the butyrates, tilt the balance to increased histone acetylation, and the resulting open chromatin conformation is generally more conducive to increased gene expression.

Histone modifications

Histone modifications include phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, ubiquitination, ADP ribosylation, carbonylation, SUMOylation, glycosylation and biotinylation. They occur at the N-terminal tail of histone molecules within a nucleosome, and have been recently described in detail in three excellent reviews (Mai, 2007; Keppler and Archer, 2008a,b;). A nucleosome consists of 146 base pairs of DNA wound round a histone octamer, made up of the four core histones (a tetramer of H3 and H4, and two dimers of H2A and H2B) of which there are many different isotypes (Kornberg and Thomas, 1974). For example, in eukaryotic genomes, histone H3 alone has been shown to have three distinct allelic variants (H3.1, H3.2 and H3.3), which exist in varying doses in different cell types (Hake et al., 2006). This review will focus predominantly on histone acetylation and methylation. However, may the reader note that there are over 150 different combinations of histone modifications known for histone H3 alone (Garcia et al., 2007), rendering the complexity of the histone code to pose a substantial dilemma for therapeutic intervention and design. Furthermore, specific modifications on histones are recognized by specific subsets of molecules, for example, acetylated histones recruit chromatin remodelling molecules containing chromo- and bromodomains. The list of such molecules is also phenomenally large and diverse, thus adding to the dilemma of specificity in drug design. These chromatin remodelling molecules marry cytosolic signal transduction pathways with epigenetic and transcriptional changes occurring in the cell's nucleus.

Histone phosphorylation offers an attractive theory for a direct link between the regulation of gene expression through the histone code and the activity of protein kinases and protein phosphatases (which add and remove, respectively, phosphate groups from serine, tyrosine and/or threonine residues) involved in cellular signalling. Phosphorylation adds a single negative charge to the histone, creating a repulsive force between histone molecules and DNA and is generally linked with gene activation. Interestingly, it has been shown that extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) initiate the cascade of histone H3 phosphorylation via downstream mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 and 2 (Msk1/2) (Soloaga et al., 2003), giving credibility to the view that kinase-regulated chromatin remodelling may play a critical role in transcriptional regulation (Keppler and Archer, 2008b).

Histone acetylation usually also neutralizes the positive charge of histone tails, decreasing their affinity for DNA, by disrupting the structured arrangement of histone molecules (and nucleosome monomers) and relaxing the chromatin structure, making it more accessible to transcription machinery binding (Zhang et al., 1998). Histone acetylation is achieved by a histone acetyl transferase (HAT) adding an acetyl group to a lysine residue (Roth et al., 2001). Conversely, HDACs remove these acetyl groups and are generally associated with chromatin inactivation (Marks et al., 2003; de Ruijter et al., 2003). However, there is increasing evidence, obtained by use of DNA microarrays to profile changes in gene expression of cell lines treated with HDAC inhibitors, demonstrating that the effect of HDAC activity on gene expression is not global, because only 1–7% of genes show altered expression (Marks et al., 2000; Zhu et al., 2001; Glaser et al., 2003), and similar results have also been reported in in vivo studies (Shafaati et al., 2009). HAT/HDAC enzymes acetylate/deacetylate a diverse range of different molecular substrates other than histones, therefore, manipulating their function with drugs will not only influence histones, but also the many other substrates dependent on their function. To date, 18 different HDACs have been discovered in humans and have been categorized into four main classes: class I (HDAC1, 2, 3 and 8), class II (HDAC4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10), class III sirtuins (SIRT1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7) and class IV (HDAC11) based on their homology to yeast HDACs (reviewed in detail by Mai, 2007). The class III sirtuins require the cofactor nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) for their active site (Michan and Sinclair, 2007), whereas all remaining HDAC classes are independent of NAD+, but, instead, contain zinc (Zn2+)-dependent active sites. The cellular localization and tissue-specific expression for each different HDAC also vary and in some instances interactions between different HDAC classes are required to activate their deacetylase function. For example, HDAC 4, 5 and 7 (class II HDACs) all lack the ability to deacetylate histones on their own; they require interaction with HDAC3 (class I) to be active (Fischle et al., 2002). The continued improvement in specificity of drugs targeting these enzymes is essential, especially given recent accounts demonstrating the potential for HDAC inhibitors to have many off target effects, including cell cycle arrest, differentiation and apoptosis (Vrana et al., 1999; Sandor et al., 2000; Hirsch and Bonham, 2004; Mai, 2007).

Histone methylation is performed by histone methylases and demethylases (Bannister and Kouzarides, 2005) at lysine, and occasionally serine residues and these residues can be mono-, di- or tri- methylated. Unlike histone acetylation and phosphorylation, histone methylation has been linked to both activation and repression of gene expression, depending on the particular residue undergoing methylation. For example, polycomb repressor complexes have been shown to associate with trimethylated histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27Me3) to achieve transcriptional silencing (Hansen et al., 2008), while trithorax molecules associate with histone H3K4Me3 to activate genes (Francis and Kingston, 2001; Santos-Rosa et al., 2002). Histone H3K9Me3 is also involved in gene repression, and the maintenance of stable heterochromatin (Sarraf and Stancheva, 2004; Schotta et al., 2004).

The extensive cross-talk between different histone modifications (within and between different histone tails) raises important issues about the action and specificity of drugs targeting epigenetic marks on histones. Combination drug therapy targeting multiple histone modifications may ultimately be required to produce effective and specific epigenetic medications.

Micro RNA

miRNAs are single-stranded transcribed non-coding RNAs, approximately 19–25 nucleotides in length and play a critical role in the regulation of messenger RNA (mRNA) translation (Bartel, 2004). They represent a third tier of epigenetic modifications, which potentially contribute to gene dysregulation and brain diseases. The biogenesis of miRNA involves multi-step processing and is dependent on the activity of several different enzymes and molecular interactions (Bartel, 2004). Biogenesis begins in the nucleus where several kilobase-long stretches of primary miRNA are transcribed from the genome and contain a polyadenylated tail at the 3′ end and a 7-methyl guanylate cap at the 5′ end of the miRNA. Through the action of Drosha (a nuclear RNase III enzyme) and its essential cofactor Pasha, it is processed into approximately 70 nucleotide (nt) long hairpin-shaped premature mRNAs (Cullen, 2004). Premature miRNAs contain a 2 nt long 3′ overhang which facilitates its export to the cytoplasm via a RanGTP/exportin-5-dependent mechanism (Bohnsack et al., 2004). The premature miRNA is then cleaved near the hairpin loop by a cytoplasmic RNase III enzyme called Dicer, releasing a RNA duplex which is approximately 22 base pairs long, with a characteristic 2 nt long 3′ overhang at both ends which contributes to the formation of the miRNA-induced RISC silencing complex (Macrae et al., 2006). The resulting single-stranded miRNA-activated RISC complex contains the argonaute catalytic component (Tomari et al., 2004), which drives the interaction and complimentary binding of miRNA with mRNA, and consequently interferes with mRNA translation to protein (Hammond, 2005).

Human miRNAs have been shown to have a very high copy number per cell. Some miRNAs can have 1000–30 000 (or more) copies per cell, whereas a large majority of mRNAs generally register less than 100 copies per cell (Sheng et al., 1994; Carter et al., 2005). This disproportionate expression is indicative of the potential for miRNA to modify the expression of an exceptionally large number of genes. Each miRNA can regulate hundreds if not thousands of mRNA targets, a theory strongly reinforced by the discovery of ‘miRNA recognition elements’ present in 3′ untranslated regions (3′UTR) of numerous mRNAs that are regulated by a single miRNA (Lewis et al., 2003; 2005; John et al., 2004; Kiriakidou et al., 2004; Lim et al., 2005). Furthermore, another recent study demonstrated that less abundantly expressed miRNAs were able to induce rapid changes in synaptic plasticity (Kye et al., 2007). It is noteworthy that the clinical implications of an abnormality or disturbance to the already complex system of miRNA-mediated regulation are substantial, especially if the abnormality occurs during the development of the central nervous system. Evidence supporting this notion comes from aberrant miRNA-mediated regulation in Tourette's syndrome (Abelson et al., 2005) and fragile X mental retardation (Jin et al., 2004). Specific examples of miRNA dysregulation in Huntington disease (HD), Alzheimer disease (AD) and schizophrenia (SZCD) can be found in the relevant sections of this review.

Pharmacology of epigenetics

In the following section, we discuss the different classes of drugs that act on various components of the epigenome. Over the past few years, it has become apparent that a number of drugs and dietary constituents, some widely used clinically, have actions on various components of the epigenome. These include various HDAC inhibitors, DNMT inhibitors, cofactors that are essential for the enzymatic activity of epigenetic modifiers and compounds that compete with typical substrates for the active sites of such enzymes (see also Figure 1).

HDAC inhibitors

As mentioned previously, HDACs catalyse the transfer of acetyl groups to lysine residues (within many different molecules, not just histone N-terminal tails). Histone acetylation homeostasis (see Figure 1) is maintained by a complex interplay between the redundant activities of different HDAC and HAT enzymes (Marks et al., 2003; de Ruijter et al., 2003). Mutation or inhibition of one enzyme therefore results in the relative overactivity of the other (Xu et al., 2007). By reducing deacetylation, HDAC inhibitors tilt the balance towards increased acetylation of substrates. HDAC inhibition has been associated with the up-regulation of a number of putatively protective genes and molecular pathways which appear to have a broad acting role in neuroprotection (Abel and Zukin, 2008). Commonly used HDAC inhibitors are valproic acid (VPA), trichostatin A and sodium and phenyl butyrate. VPA, which is more commonly known for its function as an anti-convulsant mood-stabilizing drug, has been shown to have roles in up-regulation and down-regulation of genes (Lagace et al., 2004; Blaheta et al., 2005). Long-term treatment with VPA has been shown to have neuroprotective effects on neurones which may, at least in part be due to the more recently discovered role of VPA acting as an HDAC inhibitor (Gottlicher et al., 2001; Phiel et al., 2001). HDAC inhibitors such as VPA have many other actions on brain cells, some of which may reduce brain injury and enhance brain repair in neurodegenerative disorders. For example, HDAC inhibitors can reduce brain inflammation by inducing microglia apoptosis (Dragunow et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2007b), and also promote neurotrophin production by astrocytes (Chen et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2008c). VPA may also directly or indirectly induce DNA demethylation through HDAC inhibition (Detich et al., 2003; Dong et al., 2007). Increased histone acetylation generally opens up the chromatin structure, enabling easier accessibility for transcriptional machinery and, therefore, as a general rule of thumb, treatment with HDAC inhibitors would be expected to promote increased gene expression. Although the roles of sirtuins are not discussed in this review, the reader is directed to two excellent reviews on this topic. These HDACs are not affected by conventional HDAC inhibitors because they have a different active site (NAD+ versus Zn2+), and there is growing interest in their role, especially in the ageing brain and in AD (Kim et al., 2007a), and in novel drug design targeting this subset of HDACs (Lavu et al., 2008; Brooks and Gu, 2009).

DNA methylation modifiers

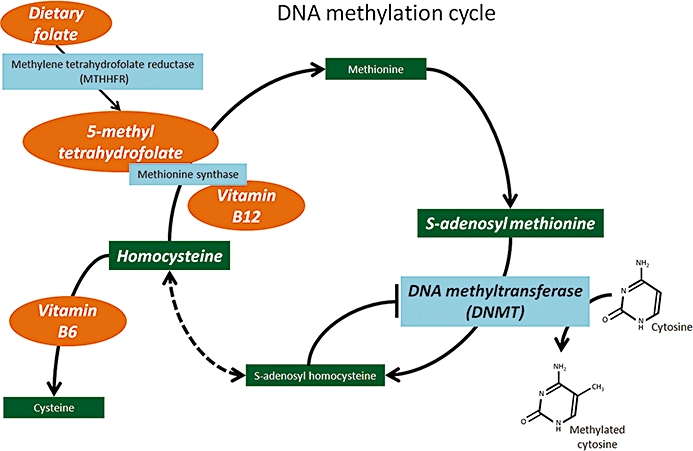

Maintenance of DNA synthesis, repair and DNA methylation are all processes largely dependent on the availability of micronutrients and vitamins, which serve as essential cofactors. Folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12 and S-adenosyl methionine will be discussed in this review. Maternal deficiency in these nutrients during pregnancy increases the risk of neural tube defects such as spina bifida (Steegers-Theunissen et al., 1994; Daly et al., 1995) due to compromised DNA methylation processes. DNMTs catalyse the transfer of methyl groups from S-adenosyl methionine to cytosine residues within CpG-rich regions of the genome (see Figure 2). This reaction is dependent on the clearance of by-products, and replenishment of substrates and cofactors. The by-product of this reaction, S-adenosyl homocysteine, is converted to homocysteine, which in turn is either catabolized or recycled to form methionine. The remethylation of homocysteine to methionine is catalysed by methionine synthase (Jensen and Ryde, 2003), an enzyme that requires vitamin B12 and 5-methylhydrofolate. Dietary folate needs to be continually replenished as it is consumed in conversion to its main circulating form, 5-methyl tetrahydrofolate, via methyltetrahydrofolate reductase, and it has been shown that dietary folate depletion can reduce genomic DNA methylation (Jacob et al., 1998). The alternate catabolic clearance of homocysteine to cysteine requires vitamin B6 as an essential cofactor for conversion. A deficiency in these cofactors results in reversal of the cycle, whereby homocysteine is reconverted to S-adenosyl homocysteine, which inhibits DNMT/DNA methylation. Elevated homocysteine levels can impair DNA repair mechanisms and induce oxidative stress, leading to death or dysfunction of cells in the nervous system (Kruman et al., 2002; Seshadri et al., 2002; Shea and Rogers, 2002). In mouse models, it has been demonstrated that dietary folate stimulates the clearance of homocysteine and may therefore hold promise in protecting cells against disease processes (Rampersaud et al., 2000; Shea and Rogers, 2002).

Figure 2.

Dietary components that can alter epigenetics. The enzymes involved in the DNA methylation cycle are dependent on the availability of essential cofactors: folate, and vitamins B12 and B6. In their abundance, DNA methyl transferases (DNMTs) readily transfer methyl groups to cytosine residues; however, in the absence of appropriate cofactors, methionine is converted back to its precursors, homocysteine and S-adenosyl homocysteine. Excess S-adenosyl homocysteine levels inhibit DNMT activity, thus they can reduce/prevent DNA methylation and compromise gene silencing. The cycle can be potentially rescued by supplementation with these essential vitamins, to clear elevated homocysteine levels and restore DNA methylation processes.

DNMT inhibitors such as 5-azacytidine (5-Aza) reduce DNA methylation (Jones et al., 1983). It has been shown that this inhibition is achieved through the covalent sequestration of DNMTs as opposed to the direct removal of methyl groups from DNA (Juttermann et al., 1994). However, some studies have shown that DNMT inhibitors can induce hypomethylation and promote gene activation (Ley et al., 1983; Escher et al., 2005).

Anthracyclines

Anthracyclines are more commonly known for their role as anti-tumour antibiotics. Mithramycin and chromomycin have been shown to interfere with the binding of transcriptional activators to the cognate CpG-rich promoter regions, and to inhibit the expression of genes that activate oxidative stress and apoptotic pathways (Chatterjee et al., 2001). CpG-rich regions are prime targets for DNA methylation; therefore, given that anthracyclines target these areas, they also fall under the category of epigenetic modifiers.

In the following discussion, we draw on examples of different epigenetic modifiers used in the context of different brain disorders to discuss the effectiveness and limitations of each treatment, and address important considerations in epigenetic therapeutics. Epigenetics is involved in a range of brain disorders including Rett syndrome, anxiety and depressive disorders, SCZD, AD, HD and many others. In this review, we will focus our discussion on HD, AD and SCZD.

Evidence for epigenetic dysregulation in brain disorders

The normal state of the epigenome in the human brain and how this is altered in brain diseases are not well understood. It is known that epigenetic modifications are highly complex and tightly regulated via the interplay of enzymes with opposing actions. However, how a balance in the opposing activity of the different enzymes, for example, HATs and HDACs, is maintained to achieve tightly regulated patterns of histone acetylation is poorly understood. If epigenetic dysregulation does truly play a part in the pathogenesis of brain disorders and neurodegeneration, then it would be fair to expect a change in the activity and/or expression of epigenetic modifiers (those regulating histone modifications, DNA methylation and non-coding RNA) and corresponding alterations in their substrates. Substantial evidence for this reasoning was provided by the discovery of neurological disorders caused by mutations in genes encoding epigenetic players (Cho et al., 2004). For example, Rett syndrome is caused by a mutation in the gene encoding MeCP2, which binds methylated DNA and recruits co-repressor complexes (Kriaucionis and Bird, 2003). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome is caused by heterozygous mutations in the gene encoding CBP [cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) binding protein] (Petrij et al., 1995), which is a histone acetyltransferase (Ogryzko et al., 1996). Mutations in the ATRX gene which encode a chromatin remodelling complex, causes several X-linked mental retardation syndromes (Gibbons and Higgs, 2000). Autism may also be epigenetically regulated (Schanen, 2006; Crespi, 2008). Environmental events such as maternal care can also have marked influences on brain function through epigenetic mechanisms (McGowan et al., 2009), indicating that many brain disorders (including those mediated by the environment) may involve epigenetic modifications. It is beyond the scope of this review to detail all of this work. Rather, we will focus on the role of epigenetics in the pathogenesis of HD, AD disease and SCZD, and will discuss the therapeutic role and potential of epigenetic manipulation in corresponding model systems and clinical trials (where possible). The lessons learnt in these disorders are also applicable to other brain disorders that involve epigenetic modifications.

HD

HD is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder caused when the CAG repeat length, in the huntingtin gene, extends beyond the normal range of 17–29 CAG repeats, resulting in aberrant polyglutamine tract expansion in the huntingtin protein (Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group, 1993). The resulting mutant huntingtin protein (polyQ) is considerably resistant to proteolytic cleavage and susceptible to aggregation (Dyer and McMurray, 2001). There is increasing evidence suggesting that polyQ induces toxicity through the aggregation and inactivation of its sequestered targets (Nucifora et al., 2001), and the consequent interference in multiple cellular pathways (Kaltenbach et al., 2007). For example, polyQ aggregates can interfere with the proteasome–ubiquitin pathway, and reduce the availability of proteasomes for the degradation of key proteins involved in cell death. This causes the elevation of key cell death players such as p53 and caspase activation (Jana et al., 2001). They can also cause dysregulation of transcription through histone monoubiquitylation (Kim et al., 2008). A characteristic of the disease is the loss of medium spiny projection neurones in the neostriatum and typical clinical presentation includes progressive motor dysfunction, cognitive decline, behavioural and emotional disturbances and weight loss. Patients are given anti-dopaminergic neuroleptics to alleviate symptoms; however, to date a cure is lacking (Adam and Jankovic, 2008; Phillips et al., 2008).

Transcriptional dysregulation appears to play a significant role in the pathophysiology of HD (Sugars and Rubinsztein, 2003;Hodges et al., 2006) and may correlate with epigenetic dysregulation (Steffan et al., 2000). Steffan and colleagues showed that polyQ sequestered and decreased CBP HAT activity with direct consequences for the epigenome. Their transgenic Drosophila model exhibited marked histone hypoacetylation, which corresponded with the transcriptional repression resulting from CBP inactivation (Steffan et al., 2000). They further demonstrated that HDAC inhibition prevented polyQ-induced toxicity and neurodegeneration (Steffan et al., 2001), and proposed a novel target for HD therapy. Jiang et al. (2006) also demonstrated that the reduced activity of CBP is directly linked to the cellular toxicity caused by polyQ. Drosophila models of HD have also been used to test inhibitors of HDAC sirtuins and RpD3 (human class I HDAC equivalent) (Pallos et al., 2008). These studies demonstrated that a greater level of neuroprotection occurred when both classes of enzymes were simultaneously inhibited (Pallos et al., 2008). A variety of these drugs have been tested in transgenic (R6/2 or N171-82Q) HD mice expressing exon 1 of the human huntingtin gene (Mangiarini et al., 1996). The following is an overview of the results obtained when these mice were used to test the therapeutic potential of drugs that could be employed to manipulate the epigenetic dysregulation observed in these HD models.

HD transgenic models generally exhibit decreased histone acetylation, which correlates with patterns of reduced gene expression. In this context, the therapeutic potential of treatment with HDAC inhibitors, such as butyrates, is based on the rationale that the relative overactivity of HATs can increase and restore histone acetylation levels. Butyrates are the most clinically studied HDAC inhibitors because they readily cross the blood–brain barrier (Egorin et al., 1999). Gardian et al. (2005) showed that mice treated with phenyl butyrate had increased histone H3 and H4 acetylation. In addition, phenyl butyrate increased the survival rate of these mice in a dose-dependent manner. Ferrante et al. (2003) observed that sodium butyrate treatment induced hyperacetylation, which corresponded with the activation of specific down-regulated genes, reduced neural and brain atrophy and improved motor performance. Overall, these studies indicate that HDAC inhibitors show great therapeutic promise for use in HD.

Conversely, there are a number of studies that demonstrate further the complexity of the relationship between histone modifications and gene expression changes. Thomas and colleagues observed that treatment with HDAC inhibitors in transgenic HD mice induced histone hyperacetylation, but decreased the expression of specific genes associated with cell death (Thomas et al., 2008). One explanation for the paradoxical changes in gene expression induced by butyrate may be due to the up-regulation of a repressor which in turn reduces the expression of the genes it regulates. Alternatively, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that a combination of many different adjacent histone modifications define the histone code and work together to dictate the accessibility of chromatin remodelling enzymes. Modification of a single histone may be dependent on adjacent histone modifications to effect changes in gene expression. This offers an alternative explanation for the disparity in the results obtained with regard to histone acetylation being linked to both gene activation and repression (Ellis et al., 2008).

HDAC inhibitors have been demonstrated to induce significant improvements in acetylation deficits and gene regulation in both in vitro (Steffan et al., 2000; Hazeki et al., 2002; Igarashi et al., 2003) and in vivo HD models. Rodent HD models, in particular, have been found to show significant improvements in survival and motor deficits (Ferrante et al., 2003; Hockly et al., 2003; Gardian et al., 2005; Sadri-Vakili et al., 2007; Thomas et al., 2008). Rodent HD models generally demonstrate histone hypoacetylation, and HDAC inhibitors have been shown to restore acetylation levels, induce both gene activation and repression and to improve neuroprotection. The patterns of histone modifications in human HD subjects are less well defined. The following provides an overview of the studies in which gene and epigenome changes in HD brain have been investigated, and the effects of therapeutic intervention on epigenome modifiers in blood and results from early-phase clinical trials.

Similar to the rodent models, human HD brain studies provide evidence for both increased and decreased gene expression. Luthi-Carter and colleagues, using microarray techniques, performed a detailed analysis of the 30 mRNAs that are increased and 30 that are decreased in different regions of HD human PM brain (Hodges et al., 2006). Ryu and colleagues compared the methylation status of histone H3 lysine 9 in the striatum and superior frontal cortex of post-mortem brain tissue from HD patients and normal controls. They showed that lysine 9 is hyper-trimethylated in HD brain (Ryu et al., 2006); H3K9Me3 generally indicates transcriptional repression (Wang et al., 2003). In line with changes in histone methylation, they found increased expression of ERG-associated protein with SET domain (ESET), a histone methyltransferase, in HD brain. A recent study by Anderson et al. (2008) provided interesting evidence for the potential role of histone hyperacetylation in human HD brain, in contrast to the hypoacetylation observed in rodent models. They observed significant increases in HAT 1 (HAT1) and in histone H3 family 3B mRNA expression in HD brain striatum and cortex respectively. They also showed gene repression in specific gene clusters such as Chr1p34, Chr17q21 and ChrXp11.2 – all of which encode HDAC genes (HDAC 1, 5 and 6 respectively). In line with previous evidence, they showed significant data for both up- and down-regulation of mRNA expression in HD compared to normal control brain. The results provide interesting evidence of a role for increased histone acetylation in human HD brain, indicative of potential species differences between transgenic rodent models and the human disease state.

Several drugs that can modify the epigenome have been tested in the clinic on patients with HD. These include VPA, sodium butyrate and phenyl butyrate. VPA is a drug commonly used for the treatment of epilepsy and bipolar disorder. Borovecki and colleagues (Borovecki et al., 2005; Runne et al., 2007) assessed mRNA profiles of a specific subset of genes from peripheral blood samples as biomarkers that correlated with HD symptoms and HDAC inhibitor treatment. In this study, microarray analysis of blood samples was used to identify distinct expression profiles in control, pre-symptomatic and symptomatic HD patients. They showed that HD symptomatic patients had an increased expression of mRNA particularly in a subset of 12 genes that were consequently used as biomarkers to measure drug effects. Treatment with phenyl butyrate significantly reduced the expression of these genes in 10 out of 12 HD patients to levels seen in matched controls. Case studies of the use of VPA in HD patients with choreatic hyperkinesia have demonstrated that the drugs are tolerated well, but in general show no improvement in clinical status (Lenman et al., 1976; Shoulson et al., 1976; Tan et al., 1976; Bachman et al., 1977; Caraceni et al., 1977; Pearce et al., 1977; Symington et al., 1978). There is one study where it was found that VPA improved the motor score of HD patients with myoclonic hyperkinesia in a dose-dependent manner (Saft et al., 2006). While myoclonus is a rare feature of HD, one cannot rule out the possibility that the properties of an HDAC inhibitor may have a role in this specific subset of patients. A recent phase 2 clinical trial tested lithium (glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibitor) administered with or without VPA (HDAC inhibitor) in HD patients, to investigate the potential of this combination therapy to alter and improve the expression levels of neurotrophic factors (such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor; BDNF, which is reduced in HD brain). This trial has been completed; however, the results have not yet been published (NCT00095355). The rationale for this study came from in vitro data where this combination of drugs was found to increase the expression of BDNF in cultured neurones (Yasuda et al., 2009). Other early-phase clinical trials have demonstrated that sodium phenyl butyrate is safe to use and tolerated well in HD patients (Hogarth et al., 2007). However, changes in disease outcome are yet to be published from pending clinical trials (NCT00212316).

As discussed previously, complimentary binding of miRNA to mRNA interferes with mRNA translation to protein. This is a highly regulated process, and a considerable number of molecular players are involved in facilitating the actions of miRNA. There is increasing evidence suggesting that dysregulation in miRNA expression and its regulatory molecules may play a role in neurodegeneration. The miRNA pathway has been shown to modulate polyQ-induced toxicity and neural degeneration. Bilen et al. (2006) showed that Dicer inactivation and the resulting decrease in miRNA levels exacerbated polyQ-related neurotoxicity in human cells. They also showed that the expression of a construct encoding miRNA ban was able to suppress the degeneration associated with polyQ-mediated toxicity, whereas loss of ban enhanced degeneration. Other evidence for a role for miRNA dysregulation in HD comes from studies linked to the transcription repressor, RE1 silencing transcription factor (REST). REST is involved in silencing neuronal gene expression, and under normal physiological conditions is sequestered by Huntington protein and prevented from translocating to the nucleus. In HD brain, however, polyQ is unable to bind REST, resulting in its translocation to the nucleus, enabling it to mediate the dedifferentiation of cells of the neuronal phenotype (Zuccato et al., 2003). This group went on to demonstrate that there is a loss of several neuronal-specific precursor miRNAs in rodent HD models and in post-mortem HD brain, resulting in increased levels of their target mRNAs (Zuccato et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2008). A recent study by Packer et al. (2008) demonstrated that several neuronal-specific mature miRNAs such as miR9 and miR9*, encoded upstream of REST binding sites, become dysregulated with disease progression in HD cortices compared to normal control. Interestingly, these two studies showed opposite trends in the dysregulation of miRNA in disease (Johnson et al. showed decreased miRNA expression, while Packer et al. showed increased miRNA expression). Potential explanations for this disparity include differences in the disease grade of post-mortem brains between studies and also differences in post-translational modifications (Obernosterer et al., 2006) influencing the regulation and expression levels of miRNA (precursor versus mature) in the different studies.

Overall, there has been a great deal of work investigating the role of epigenetic processes in HD. The results are complicated and at times contradictory, but there is ample evidence that alterations in epigenetic pathways are involved in the aetiology of HD. Most studies, in which either cell lines or transgenic animals expressing polyQ have been used, show evidence of reduced histone acetylation. HDAC inhibitors generally provide positive outcomes in these models (i.e. ‘disease’ amelioration), although, so far, their effects in humans with HD have been much less impressive. Some human studies hint at increased histone acetylation; however, this runs counter to the work using cell lines and transgenic animals. It will be vital in future studies to investigate and compare specific histone modifications in the model systems, and the human condition to determine which, if any, of the models are valid. However, as repeatedly pointed out in this review, epigenetic modifications are very complex and changes in gene expression are not in any simple way related to changes in histone acetylation. An understanding of this complexity may provide future opportunities to treat the epigenetic ‘lesions’ in HD.

AD

AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder resulting in severe dementia, with a decline in a broad range of memory and cognitive functions. Specific anatomical changes correspond with the cognitive decline that takes place in the AD brain. The main region that becomes compromised is the medial temporal lobe (Braak and Braak, 1995). There is marked atrophy of neuronal populations within this region and the connections it forms with other areas of the brain, and this is reflected in the enlargement of the fluid-filled ventricles and thinning of brain gyri. This part of the brain also presents the highest density of histopathological hallmarks related to AD: neurofibrillary tangles (paired helical filaments associated with aberrantly hyperphosphorylated tau, NFT) and β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques (Giannakopoulos et al., 1998). There is a diverse range of genetic, dietary, environmental, inflammatory and age-related factors that have been shown to dictate susceptibility to sporadic AD. Less than 1% of all cases are familial cases of AD caused by mutations in either amyloid precursor protein (APP) (Goate et al., 1991) or presenilin (PSEN) genes (Clark et al., 1995).

The amyloid hypothesis is the dominant theory for the pathogenesis of AD (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002). The APP is a transmembrane protein, which undergoes sequential proteolytic cleavage. The first cleavage is by either α-secretase or β-secretase, which liberates almost the entire (extracellular) ectodomain, releasing soluble APP domains αAPPs and βAPPs respectively. The major neuronal β-secretase is also known as BACE1 (Vassar et al., 1999). The second cleavage is performed by γ-secretase which is a PSEN (either PSEN1 or PSEN2)-dependent enzyme (Citron et al., 1997; De Strooper et al., 1998), and produces the APP intracellular domain (AICD, also known as an APP C-terminal fragment, APP-CT) and either a 3 kDa protein (p3, when in combination with α-secretase) or Aβ peptides (when in combination with β-secretase cleavage). Aβ peptides are major constituents of AD amyloid plaques (Zheng and Koo, 2006). Given that APP is encoded by a gene found on chromosome 21, the pathological change observed due to the over-expression of APP in (trisomy 21) Downs syndrome brain reaffirms that APP gene dosage is an important factor in the neuropathology of AD. All familial AD-related APP mutations have been positioned near the secretase cleavage sites and are believed to interfere with APP processing, resulting in increased Aβ synthesis. There is increasing evidence that the dysregulation of epigenetic mechanisms may also influence the expression of APP.

Yoshikai and colleagues considered APP to be a potential gene to be controlled by methylation (Yoshikai et al., 1990). They showed that the APP promoter region had a high GC content (72%). Rogaev et al. (1994) looked at whether variable methylation status influenced the expression of APP in different regions of the brain (neocortex, cerebellum) and other tissues. They were able to demonstrate tissue-specific and brain region-specific patterns of methylation of the APP promoter. West et al. (1995) found differences in methylation status of the APP gene between a patient with AD, Picks disease and a normal control individual. Tohgi et al. (1999) also looked at the methylation status of DNA extracted from the parietal cortex in post-mortem brains from 10 neurologically normal individuals. They observed decreasing amounts of methylcytosine within the APP promoter with increasing age (a known risk factor for AD), in agreement with several other studies (Wilson and Jones, 1983; Wilson et al., 1987; Cooney, 1993). Another early study raised interesting questions about the potential genomic redistribution of methylated cytosine residues in AD which may influence a select population of critical brain-specific genes (Schwob et al., 1990). A recent study compared promoter methylation of genes encoding critical components of epigenetic machinery in late-onset AD patient brain tissue to controls using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. They found significant inter-individual variation particularly in genes that participate in methylation homeostasis (MTHFR and DNMT1) in AD patients compared to the median methylation patterns of healthy control individuals, and they suggested that this may contribute to AD predisposition (Wang et al., 2008a). However, this group also failed to replicate the hypomethylation of the APP gene observed in previous studies. Another study using immunostaining-based techniques investigated changes in key epigenetic markers in post-mortem AD compared to control brain tissue. They showed that immunoreactivity for methylcytosine, DNMT1 and components of the methylation co-repressor complex was markedly decreased in AD cases, and these results strengthen the argument for loss of methylation of APP playing a role in AD (Mastroeni et al., 2008). Furthermore, a group evaluated the effect of 5-Aza in peripheral leucocytes from normal, aged and AD patients. They showed that the many sites that were originally methylated became more readily and rapidly unmethylated in cells from AD patients compared to control and aged subjects, suggesting that epigenomic regulation may be compromised in AD patients more than in control subjects (Payao et al., 1998).

Folate and vitamin B12 are essential cofactors required to regenerate methionine (precursor to S-adenosyl methionine, the methyl donor for DNA methylation) from homocysteine. Elevated levels of homocysteine have been observed in AD patients, and are associated with folate and vitamin B12 deficiency (Seshadri et al., 2002; Morris, 2003). Kruman and colleagues showed that folate deficiency and elevated homocysteine levels in APP mutant mice impaired DNA repair mechanisms in hippocampal neurones, sensitizing them to oxidative damage induced by Aβ (Kruman et al., 2002). In addition to this, Shea and Rogers (2002) showed that oxidative stress is increased in the brains of APOE ε4 positive mice, and they showed that this effect can be suppressed by the addition of folate. The ε4 allele of the APOE gene is a known risk factor for both early-onset familial and late-onset sporadic AD cases (Corder et al., 1993; Saunders et al., 1993). Folate deficiency can also arise from polymorphisms in 5′ 10′ methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), also a risk factor for AD (Friso et al., 2002). The resulting elevated homocysteine levels and corresponding decrease in S-adenosyl methionine in AD (Tchantchou et al., 2006) may decrease APP promoter methylation and augment the increased expression of APP, and in this way fuel increased Aβ load. Several recent studies have tested the benefits of high-dose supplements of folate, vitamin B12 and vitamin B6 (Aisen et al., 2003; 2008;), and demonstrated that treatment reduced the elevated homocysteine levels in treated patients. However, no significant benefits were observed in cognitive function. A recent study by Chan et al. (2008) employed a more novel approach using a cocktail of folate, vitamin B6, α-tocopherol, S-adenosyl methionine, N-acetyl cysteine and acetyl-l-carnitine in early-stage AD patients, and reported significant improvements in all scoring systems (dementia rating scale, neuropsychiatric inventory and activities of daily living) for all patients.

Bertram et al. (2007) performed meta-analysis on each known polymorphism for all known AD susceptibility genes based on available genotype data from at least three independent case-control samples. A polymorphism in the MTHFR gene (A1298C) was among one of the susceptibility genes with statistically significant allelic odds ratios in accordance with previous association findings (Anello et al., 2004). It is noteworthy that exclusion of the first study (out of three) from the meta-analysis for MTHFR made the odds ratio statistically insignificant, indicating the need for a greater sample size for this variant. However, the exact role of MTHFR remains controversial, given that in other studies no significant associations were found between AD risk and MTHFR polymorphisms (Prince et al., 2001; Fernandez and Scheibe, 2005; da Silva et al., 2006). Evidence for epigenetic dysregulation in AD also comes from studies showing that the products of amyloidogenic APP processing (in particular the APP-CTs produced from β- and γ-secretase coupled cleavage) may interact with molecular players involved in chromatin modification. For example, APP-CTs produced from the amyloidogenic pathway have been shown to colocalize with Fe65 (Sumioka et al., 2005) and Tip60 (Cao and Sudhof, 2001; von Rotz et al., 2004; Telese et al., 2005; Slomnicki and Lesniak, 2008). FE65 is an adapter protein, which contains two PTB domains. The PTB2 domain interacts with AICD (McLoughlin and Miller, 2008) and is involved in facilitating the proteolytic cleavage of AICD and its translocation to the nucleus (Wiley et al., 2007). This process is mediated by other transcription factors, including Tip60, which also possesses HAT activity and consequently, upon translocation to the nucleus, increases histone acetylation (Cao and Sudhof, 2001). Kim et al. (2004), using in vitro models (PC12 cells and rodent primary cortical neurones), demonstrated that APP-CTs induced histone H3 and H4 hyperacetylation, and up-regulated the expression of cytotoxic genes. They also showed that this effect is exacerbated by the administration of the HDAC inhibitor sodium butyrate (Kim et al., 2004). It may be that the genes up-regulated downstream of Tip60-mediated histone acetylation are involved in driving apoptosis (Ikura et al., 2000). The use of HAT inhibitors may hold great therapeutic potential for AD treatment, given the evidence for increased histone acetylation in AD brain. This is supported by studies showing that the risk of developing AD is significantly reduced in a population that consumes large quantities of curcumin (Chandra et al., 1998; 2001;), a HAT inhibitor that has been shown to interfere with the formation of amyloid plaques in AD rodent models (Lim et al., 2001; Ono et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2005; Ishrat et al., 2009). Two clinical trials (NCT00088710 and NCT00164749) have been completed where the therapeutic efficacy of curcumin was evaluated in probable AD patients. However, the results have not yet been released. The exact role of the AICD–Fe65–Tip60 interactions remains controversial, particularly in light of recent reports where Fe65 and its interaction with AICD are shown to have important roles in the response to DNA damage. Their interaction is shown to assist Tip60-TRRAP to DNA damaged sites (Stante et al., 2009), whereby increased histone acetylation opens up the chromatin structure to enable DNA repair.

The use of HDAC inhibitors in humans has so far not been successful. A recent clinical trial demonstrated significant worsening of agitation and aggression in AD patients receiving VPA compared to placebo (Herrmann et al., 2007). In addition to this, the effectiveness of VPA in treating behavioural symptoms in elderly dementia patients with agitation and aggressive behaviours has been limited; low doses of VPA fail to reduce agitation in all patients, and high doses in some patients with unacceptable adverse effects (Lott et al., 1995; Kasckow et al., 1997; Narayan and Nelson, 1997; Porsteinsson et al., 1997; 2001; 2003; Herrmann, 1998; Kunik et al., 1998; Tariot et al., 2001; 2005; Sival et al., 2002; Forester et al., 2007). As with HD, it is evident that the level of epigenetic dysregulation underlying AD is complicated by the sheer number of different molecular players and different mechanisms involved. While HDAC inhibition may have limited benefits in AD patients and dementia, alternative methods to manipulate the general DNA hypomethylation observed in AD may hold greater therapeutic promise.

There is growing evidence suggesting that nutritional deficiencies may also influence epigenetic dysregulation and contribute to the pathogenesis of AD. As proposed by Lahiri et al. (2008), environmental cues such as diet, metal exposure, maternal care and intrauterine exposures (Zhang et al., 2007) may perturb gene regulation during early development and increase susceptibility to developing pathological deficits much later in life (Mattson and Shea, 2003; Fusco et al., 2007). An example of how maternal intrauterine environment can influence and induce epigenetic changes in offspring that present pathologically later in life are evident in a recent study by Zhang and colleagues (Barik, 2007; Zhang et al., 2007). They demonstrate that neonatal cocaine exposure in pregnant rats causes aberrant DNA methylation at an enhancer region of the PKCε gene. This prevents the binding of AP1 transcription factor and leads to abrogation of the expression of PKC in the foetal heart tissue, predisposing the offspring to increased risk of heart disease. This particular example strengthens the notion that early life experiences and developmental exposures could also condition offspring susceptibility to other complex disorders such as AD or anxiety disorders later in life. For example, Basha and colleagues demonstrated that developmental exposure of neonates to lead (Pb) caused a delayed over-expression of APP and increased Aβ load 20 months after Pb exposure had ceased (Basha et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2008b). A similar study in aged monkeys also showed that the effects of developmental Pb exposure caused a reduction in DNA methyltransferase activity in adulthood, as well as increased expression of AD-related genes (Wu et al., 2008a). Such environmental cues could alter DNA methylation, and this could be a mechanism whereby perturbed early life events predispose individuals to epigenetic dysregulation and the development of AD in later life.

As mentioned previously, miRNAs recognize specific binding sites on the 3′UTR of mRNA sequences, and depending on the extent of their complementary binding, miRNAs can regulate the translation of mRNA to protein. The exact role of miRNA-mediated regulation of genes implicated in the pathogenesis of AD is currently not well understood; however, this is a rapidly growing area of research. Significant clues supporting a role for miRNA in AD come from the disproportionate levels of inexpression of mRNA and protein of the neuronal specific β-secretase, BACE1 (Fukumoto et al., 2002; Holsinger et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2003) in AD brain. In a recent study, the role of the BACE1 3′UTR and whether it is targeted and regulated by miRNAs was investigated (Boissonneault et al., 2009). It was demonstrated that the 3′UTR of BACE mRNA contains specific binding sites recognized by miR-298 and miR-328. These miRNAs were shown to regulate the translation of BACE1 mRNA in two different neuronal cell types in vitro. Wang et al. (2008b) found that miR-107 also targets the 3′UTR of BACE1 mRNA. Alterations in the expression of non-coding RNA (Faghihi et al., 2008) or of miR-106a and miR-520c (Patel et al., 2008), or miRNAs belonging to the miR-20a family (Hebert et al., 2009) or miR-29a/b-1 cluster (Hebert et al., 2008) have been implicated in the regulation of APP and/or BACE1 expression (and their potential dysregulation in the context of AD). Another group recently showed that aberrant miRNA-mediated processing of mRNA can lead to abnormal levels of mRNA and consequent neuronal dysfunction in AD brain hippocampus post-mortem when compared to normal fetal and adult brain hippocampi (Lukiw, 2007; Sethi and Lukiw, 2009). Altered miRNA expression in the cerebrospinal fluid of AD patients was found to correlate with altered patterns in AD brain and could be used in the future as a potential biomarker for diagnosis and/or for measuring treatment efficacy (Cogswell et al., 2008). While this is a rapidly growing field, the exact role of miRNA in AD pathogenesis awaits thorough characterization.

Schizophrenia

SCZD is a severe psychiatric disorder for which the pathophysiology remains largely unknown. One recent review reports that compromised epigenetic regulation of gene expression may determine an individual's susceptibility to gene–environment interactions which contribute to onset of the disease (Dean et al., 2009). SCZD is a complex group of disorders, and a large body of evidence implicates a substantial genetic component playing a role in its pathogenesis (Egan et al., 2001; Stefansson et al., 2002; Harrison and Weinberger, 2005). However, studies of discordant SCZD in identical twins also argue for the involvement of potential epigenetic factors in the pathogenesis of SCZD (Goldberg et al., 1990; Weinberger et al., 1992; Cannon et al., 2000). It may be that some epigenetic signals have partial meiotic stability depending on exposure to specific environmental cues, which lead to the transmission of disease from one generation to the next. This type of regulation may explain the ambiguity of inherited SCZD and may reflect the dissimilarity of epigenetic forms of inheritance to Mendelian patterns of inheritance. Evidence supporting this notion comes from studies showing that elevated homocysteine levels in the intrauterine environment of a developing fetus may predispose individuals to SCZD (Brown et al., 2007). Brown and colleagues showed that elevated homocysteine levels in the third trimester in utero increased the risk for SCZD through altered macromolecule methylation contributing to epigenetically based disruption of neurodevelopment during fetal life.

DNA methylation is sensitive to environmental cues (Jaenisch and Bird, 2003). It has been shown that genes which have an important role in synaptic plasticity and GABAergic function are repressed in the SCZD brain. These include decreases in reelin (an extracellular matrix protein) and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD67, an important enzyme involved in GABA synthesis) in a specific subset of telencephalic GABAergic interneurones in post-mortem brain of schizophrenia patients (Akbarian et al., 1995; Impagnatiello et al., 1998). Phenotypic traits associated with reelin haplo-insufficiency in heterozygous reeler mice are suggested to be analogous to the psychosis vulnerability observed in SCZD (Tueting et al., 1999). It has also been shown that SCZD patients have elevated homocysteine levels, and their corresponding promoters are hypermethylated (Abdolmaleky et al., 2005; Grayson et al., 2006; Huang and Akbarian, 2007; Mill et al., 2008). These alterations are probably due to the threefold significant increase in levels of DNMT1 in complimentary areas of SCZD brain (Veldic et al., 2004; Grayson et al., 2005). A shift in histone methylation patterns from transcriptionally active (H3K4Me3) to repressed (H3K27Me3) may also play a role in regulating the expression of another important GABAergic gene, glutamate decarboxylase 1 (GAD1) (Benson et al., 1994; Addington et al., 2005; Lundorf et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2007), which is also implicated in the pathogenesis of SCZD. Chen and colleagues demonstrated in vitro that the DNMT inhibitor, 5-Aza reversed reelin promoter hypermethylation and induced a 60-fold increase in mRNA levels. They also reported that the HDAC inhibitors VPA and TSA induced the activation and expression of endogenous reelin (Chen et al., 2002). Sharma et al. (2008) recently reported that HDAC1 expression levels are significantly higher in the prefrontal cortices from post-mortem brain of SCZD patients compared to normal controls.

HDAC inhibitors have also shown promise in in vivo and in vitro models. VPA, for example, in the reeler and epigenetic (methionine-induced) mouse model reverses hypermethylation of reelin and GAD67 gene promoters, and increases histone H3 acetylation and reverses behavioural changes (Tremolizzo et al., 2002; 2005; Dong et al., 2007). Kundakovic et al. (2009) showed that HDAC and DNMT inhibitors were effective in the disruption of co-repressor complexes and in the activation of reelin and GAD67 in vitro. An interesting study by Satta and colleagues revealed that smoking addiction in schizophrenic patients may represent nicotine self-medication as an attempt to correct nicotinic acetylcholine receptor dysfunction. They showed that nicotine administration decreases DNMT1 mRNA levels, and increases GAD67 expression through the activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on cortical and hippocampal GABAergic interneurones (Satta et al., 2008). The chromatin of schizophrenic patients has been shown to be more resistant to alteration by HDAC inhibitors compared to bipolar patients (Sharma et al., 2006). While such drugs induce significant improvements in GAD67 and reelin expression in reeler mice, their effects are substantially less pronounced in human patients. However, in light of this, HDAC inhibitors appear to act as an adjuvant, softening the chromatin and enabling patients to benefit significantly more from conventional drugs (Gavin et al., 2009). For example, the co-administration of VPA with antipsychotics (clozapine, and sulpride) accelerates the demethylation of reelin and GAD67 genes (Dong et al., 2008; Guidotti et al., 2009). A very recent study provides interesting evidence for the use of S-adenosyl methionine in ameliorating aggressive symptomatology in a subpopulation of schizophrenic patients with low catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) enzyme activity (Strous et al., 2009). This study showed that S-adenosyl methionine treatment, a primary methyl group donor for COMT (and DNMT), increased COMT activity in patients with low-activity COMT polymorphism and reduced aggression, and in female patients also reduced depressive symptoms. However, the advantageous effects of methionine may be limited only to this subpopulation of SCZD patients as there is also evidence showing that SCZD symptomatology is exacerbated by treatment with large doses of methionine, while the same treatment has no behavioural or cognitive effects on normal subjects (Cohen et al., 1974).

The miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional gene silencing is thought to have a role in the pathophysiology of SCZD. A recent study showed that the levels of miR-181b are significantly up-regulated in the superior temporal gyrus (STG) of SCZD post-mortem brains compared to non-psychiatric controls (Beveridge et al., 2008). STG contains primary and secondary auditory visual cortices which are thought to be regions involved in the generation of auditory hallucinations and is shown to have a reduced volume in SCZD brain (Rajarethinam et al., 2000). The increase in miR-181b expression was inversely proportional to the observed decrease in levels of SCZD-associated target genes such as those encoding the ionotropic AMPA glutamate receptor subunit and the calcium sensor gene visinin-like 1. These genes have been shown to have important roles in the development of synaptic plasticity (Carroll et al., 2001) and the response of hippocampal neurones to glutamate stimulation (Spilker et al., 2002) respectively. Another recent study (Zhu et al., 2009) showed that miR-346 is reduced in SCZD post-mortem brain. It is encoded by a gene found in an intron of the glutamate receptor ionotropic delta 1 gene that has also been associated with SCZD (Guo et al., 2007). In this study, miR-346 is predicted to target other SCZD susceptibility genes with high frequency, and therefore the observed reduction in miR-346 expression is indicative of the potential for dysregulation in its target genes (Zhu et al., 2009). This notion was also reinforced by the observation that miR-195 negatively regulated the expression of BDNF, which in turn regulates the expression of GABAergic markers such as neuropeptide Y and somatostatin, suggesting that alterations in miRNA-mediated regulation of these genes may also have a role in the pathophysiology of SZCD (Mellios et al., 2009). In combination, these results suggest that altered miRNA levels may underlie the dysregulation in cortical gene expression observed in SCZD brain (Eastwood et al., 1995; Vawter et al., 2002).

The pathoaetiology of SZCD may be linked to alterations in the expression and/or function of miRNAs. Hansen et al. (2007) analysed genetic variants of miRNA expressed in the brain of SCZD patients compared to control subjects. They found a nominal association between SCZD and single nucleotide polymorphisms located in miR-206 and miR-198, and suggest that such allelic differences may alter that interaction between miRNA and mRNA, and contribute to the phenotypic variation observed under the SCZD disease umbrella. Perkins et al. (2007) demonstrated that seven human miRNAs were significantly reduced in post-mortem prefrontal cortex of SCZD brain compared to normal controls.

Increasing evidence suggests that schizophrenia, instead of defining a discrete disease, may probably define a syndrome encompassing a complex group of diseases that may arise from common aetiology, but shared additional traits (Allen et al., 2009), based on the specific subset of genes dysregulated within a given group of patients. Dean et al. (2009) proposed that the specific subsets of genes is probably regulated by specific epigenetic mechanisms. These epigenetic mechanisms may be abrogated by certain environmental cues (e.g. intrauterine exposures, dietary deficiencies, gene polymorphisms or an accumulation of all of these) early in life, predisposing individuals to a specific endophenotype later in life. Such observations may provide an explanation for why one subpopulation (low activity COMT polymorphism) of SCZD patients benefit from the administration of S-adenosyl methionine, while another subpopulation (hypermethylated reelin and GAD67) may benefit from DNMT and/or HDAC inhibition.

Concluding remarks

The preceding discussion shows that epigenetic processes are involved in a range of psychiatric and neurological disorders. Some of these disorders although manifesting later in life (e.g. SCZD, AD) may partly have developmental origins that are mediated by epigenetic modifications, which may be amenable to pharmacological intervention. However, whether the pharmacological manipulation of individual components of the epigenome will provide successful therapeutic outcomes is unclear, particularly because current treatments are unable to target specific genomic sites, and this may increase the risk of off-target responses. Future studies using class and subtype-specific HDAC inhibitors (as well as drugs which modify other histone marks such as methylation and phosphorylation), alone and also in combination, may provide greater specificity of action and generate better therapeutic outcomes with fewer side effects. The possibility of epi-genotyping individuals from blood samples or identifying epigenetic biomarkers to first define an individual's epigenome may allow for the tailoring of epigenetic drugs to specific epigenomes. Clearly, the pharmacology of epigenetics is in its infancy. However, the widespread impact of epigenetic modifications in diseases of the brain (and other organs) suggests that this will be a rich source of therapeutic intervention in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Research Centre for Growth and Development to M.D., and by a Seelye Trust PhD Scholarship to P.N.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- 5-Aza

5-azacytidine

- Aβ

β-amyloid plaques

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- CBP

cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB)

- COMT

catechol-o-methyltransferase

- DNMT

DNA methyl transferase

- ERK1/2

extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2

- ESET

ERG-associated protein with SET domain

- GAD67

glutamic acid decarboxylase

- HAT

histone acetyl transferase

- HD

Huntington disease

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- MAPKs

p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases

- MBD1-3

methyl CpG binding domain proteins 1–3

- MeCP1, MeCP2

methyl CpG binding protein 1 and 2

- Msk1/2

mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 and 2

- MTHFR

5′ 10′ methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase

- NAD+

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NFT

neurofibrillary tangles

- SCZD

schizophrenia

- TSA

trichostatin A

- VPA

valproic acid

Conflict of interest

The authors know of no conflict of interest relevant to this review article.

References

- Abdolmaleky HM, Cheng KH, Russo A, Smith CL, Faraone SV, Wilcox M, et al. Hypermethylation of the reelin (RELN) promoter in the brain of schizophrenic patients: a preliminary report. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;134B:60–66. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel T, Zukin RS. Epigenetic targets of HDAC inhibition in neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abelson JF, Kwan KY, O'Roak BJ, Baek DY, Stillman AA, Morgan TM, et al. Sequence variants in SLITRK1 are associated with Tourette's syndrome. Science. 2005;310:317–320. doi: 10.1126/science.1116502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam OR, Jankovic J. Symptomatic treatment of Huntington disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:181–197. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington AM, Gornick M, Duckworth J, Sporn A, Gogtay N, Bobb A, et al. GAD1 (2q31.1), which encodes glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD67), is associated with childhood-onset schizophrenia and cortical gray matter volume loss. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:581–588. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aisen PS, Egelko S, Andrews H, Diaz-Arrastia R, Weiner M, DeCarli C, et al. A pilot study of vitamins to lower plasma homocysteine levels in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:246–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aisen PS, Schneider LS, Sano M, Diaz-Arrastia R, van Dyck CH, Weiner MF, et al. High-dose B vitamin supplementation and cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:1774–1783. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbarian S, Kim JJ, Potkin SG, Hagman JO, Tafazzoli A, Bunney WE, Jr, et al. Gene expression for glutamic acid decarboxylase is reduced without loss of neurons in prefrontal cortex of schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:258–266. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950160008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen AJ, Griss ME, Folley BS, Hawkins KA, Pearlson GD. Endophenotypes in schizophrenia: a selective review. Schizophr Res. 2009;109:24–37. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AN, Roncaroli F, Hodges A, Deprez M, Turkheimer FE. Chromosomal profiles of gene expression in Huntington's disease. Brain. 2008;131:381–388. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anello G, Gueant-Rodriguez RM, Bosco P, Gueant JL, Romano A, Namour B, et al. Homocysteine and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroreport. 2004;15:859–861. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200404090-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman DS, Butler IJ, McKhann GM. Long-term treatment of juvenile Huntington's chorea with dipropylacetic acid. Neurology. 1977;27:193–197. doi: 10.1212/wnl.27.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Reversing histone methylation. Nature. 2005;436:1103–1106. doi: 10.1038/nature04048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barik S. The thrill can kill: murder by methylation. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:1203–1205. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.035196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basha MR, Wei W, Bakheet SA, Benitez N, Siddiqi HK, Ge YW, et al. The fetal basis of amyloidogenesis: exposure to lead and latent overexpression of amyloid precursor protein and beta-amyloid in the aging brain. J Neurosci. 2005;25:823–829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4335-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DL, Huntsman MM, Jones EG. Activity-dependent changes in GAD and preprotachykinin mRNAs in visual cortex of adult monkeys. Cereb Cortex. 1994;4:40–51. doi: 10.1093/cercor/4.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram L, McQueen MB, Mullin K, Blacker D, Tanzi RE. Systematic meta-analyses of Alzheimer disease genetic association studies: the AlzGene database. Nat Genet. 2007;39:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestor TH, Verdine GL. DNA methyltransferases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:380–389. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge NJ, Tooney PA, Carroll AP, Gardiner E, Bowden N, Scott RJ, et al. Dysregulation of miRNA 181b in the temporal cortex in schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1156–1168. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilen J, Liu N, Burnett BG, Pittman RN, Bonini NM. MicroRNA pathways modulate polyglutamine-induced neurodegeneration. Mol Cell. 2006;24:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaheta RA, Michaelis M, Driever PH, Cinatl J., Jr Evolving anticancer drug valproic acid: insights into the mechanism and clinical studies. Med Res Rev. 2005;25:383–397. doi: 10.1002/med.20027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack MT, Czaplinski K, Gorlich D. Exportin 5 is a RanGTP-dependent dsRNA-binding protein that mediates nuclear export of pre-miRNAs. RNA. 2004;10:185–191. doi: 10.1261/rna.5167604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissonneault V, Plante I, Rivest S, Provost P. MicroRNA-298 and microRNA-328 regulate expression of mouse beta-amyloid precursor protein-converting enzyme 1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1971–1981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807530200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovecki F, Lovrecic L, Zhou J, Jeong H, Then F, Rosas HD, et al. Genome-wide expression profiling of human blood reveals biomarkers for Huntington's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11023–11028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504921102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Staging of Alzheimer's disease-relatedneurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16:271–278. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00021-6. discussion 278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks CL, Gu W. How does SIRT1 affect metabolism, senescence and cancer? Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:123–128. doi: 10.1038/nrc2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS, Bottiglieri T, Schaefer CA, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Liu L, Bresnahan M, et al. Elevated prenatal homocysteine levels as a risk factor for schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:31–39. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, Huttunen MO, Lonnqvist J, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Pirkola T, Glahn D, et al. The inheritance of neuropsychological dysfunction in twins discordant for schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:369–382. doi: 10.1086/303006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Sudhof TC. A transcriptionally [correction of transcriptively] active complex of APP with Fe65 and histone acetyltransferase Tip60. Science. 2001;293:115–120. doi: 10.1126/science.1058783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraceni T, Calderini G, Consolazione A, Riva E, Algeri S, Girotti F, et al. Biochemical aspects of Huntington's chorea. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1977;40:581–587. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.40.6.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RC, Beattie EC, von Zastrow M, Malenka RC. Role of AMPA receptor endocytosis in synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:315–324. doi: 10.1038/35072500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter MG, Sharov AA, VanBuren V, Dudekula DB, Carmack CE, Nelson C, et al. Transcript copy number estimation using a mouse whole-genome oligonucleotide microarray. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R61. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-7-r61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A, Paskavitz J, Remington R, Rasmussen S, Shea TB. Efficacy of a vitamin/nutriceutical formulation for early-stage Alzheimer's disease: a 1-year, open-label pilot study with an 16-month caregiver extension. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;23:571–585. doi: 10.1177/1533317508325093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra V, Ganguli M, Pandav R, Johnston J, Belle S, DeKosky ST. Prevalence of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias in rural India: the Indo-US study. Neurology. 1998;51:1000–1008. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.4.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra V, Pandav R, Dodge HH, Johnston JM, Belle SH, DeKosky ST, et al. Incidence of Alzheimer's disease in a rural community in India: the Indo-US study. Neurology. 2001;57:985–989. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.6.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Zaman K, Ryu H, Conforto A, Ratan RR. Sequence-selective DNA binding drugs mithramycin A and chromomycin A3 are potent inhibitors of neuronal apoptosis induced by oxidative stress and DNA damage in cortical neurons. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:345–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PS, Peng GS, Li G, Yang S, Wu X, Wang CC, et al. Valproate protects dopaminergic neurons in midbrain neuron/glia cultures by stimulating the release of neurotrophic factors from astrocytes. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:1116–1125. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PS, Wang CC, Bortner CD, Peng GS, Wu X, Pang H, et al. Valproic acid and other histone deacetylase inhibitors induce microglial apoptosis and attenuate lipopolysaccharide-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity. Neuroscience. 2007;149:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.06.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Sharma RP, Costa RH, Costa E, Grayson DR. On the epigenetic regulation of the human reelin promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:2930–2939. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho KS, Elizondo LI, Boerkoel CF. Advances in chromatin remodeling and human disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citron M, Westaway D, Xia W, Carlson G, Diehl T, Levesque G, et al. Mutant presenilins of Alzheimer's disease increase production of 42-residue amyloid beta-protein in both transfected cells and transgenic mice. Nat Med. 1997;3:67–72. doi: 10.1038/nm0197-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RF, Hutton M, Fuldner RA, Froelich S, Karran E, Talbot C, et al. The structure of the presenilin 1 (S182) gene and identification of six novel mutations in early onset AD families. Nat Genet. 1995;11:219–222. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogswell JP, Ward J, Taylor IA, Waters M, Shi Y, Cannon B, et al. Identification of miRNA changes in Alzheimer's disease brain and CSF yields putative biomarkers and insights into disease pathways. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;14:27–41. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-14103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SM, Nichols A, Wyatt R, Pollin W. The administration of methionine to chronic schizophrenic patients: a review of ten studies. Biol Psychiatry. 1974;8:209–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney CA. Are somatic cells inherently deficient in methylation metabolism? A proposed mechanism for DNA methylation loss, senescence and aging. Growth Dev Aging. 1993;57:261–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261:921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]