Abstract

Guard cells adjust their volume by changing their ion content due to intense fluxes that, for K+, are believed to flow through inward or outward Shaker channels. Because Shaker channels can be homo- or heterotetramers and Arabidopsis guard cells express at least five genes encoding inward Shaker subunits, including the two major ones, KAT1 and KAT2, the molecular identity of inward Shaker channels operating therein is not yet completely elucidated. Here, we first addressed the properties of KAT1-KAT2 heteromers by expressing KAT1-KAT2 tandems in Xenopus oocytes. Then, computer analyses of the data suggested that coexpression of free KAT1 and KAT2 subunits resulted mainly in heteromeric channels made of two subunits of each type due to some preferential association of KAT1-KAT2 heterodimers at the first step of channel assembly. This was further supported by the analysis of KAT2 effect on KAT1 targeting in tobacco cells. Finally, patch-clamp recordings of native inward channels in wild-type and mutant genotypes strongly suggested that this preferential heteromerization occurs in planta and that Arabidopsis guard cell inward Shaker channels are mainly heteromers of KAT1 and KAT2 subunits.

Keywords: Biophysics, Channels/Potassium, Membrane, Methods/Computer Modeling, Tissue/Organ Systems/Oocyte, Transport, Transport/Potassium, Plant, Guard Cells, Heteromerization

Introduction

Stomata are microscopic pores in the plant leaf epidermis that allow both diffusion of atmospheric CO2 toward the inner photosynthetic tissues and water vapor loss by transpiration. Regulation of stomatal aperture allows plants to cope with the conflicting needs of enabling CO2 entry for photosynthesis and of preventing excessive water loss and desiccation. Stomatal movement results from a change in turgor of the two guard cells surrounding the pore. An increase or decrease in turgor opens or closes the stoma, respectively. This osmoregulation process involves K+ transport into and from the guard cells, which are mediated mainly by potassium channels in the plasma membrane belonging to the Shaker family (1, 2). These potassium channels were found to play pleiotropic roles in guard cells, improving stomatal reactivity to external or internal signals (light, CO2 availability, or evaporative demand) and thus enhancing the ability of the plant to adapt to fluctuating and/or stressing natural environments (1).

Plant Shaker-like K+ channels are tetrameric proteins built of four α-subunits. Each subunit consists of a hydrophobic core flanked by cytosolic N- and C-terminal regions. The hydrophobic core is composed of six transmembrane segments (S1–S6). The loop between S5 and S6 (P domain) contributes to the permeation pathway of the channel and carries the hallmark GYG(D/E) motif of highly K+-selective channels. The fourth transmembrane segment (S4) contains positively charged amino acids and is involved in the voltage-sensing process of the Shaker-like K+ channels. Hyperpolarization-activated channels mediate inward K+ currents, and depolarization- activated ones mediate outward K+ currents (3). More generally, the activity of Shaker-like K+ channels is regulated at both the transcriptional and post-translational levels. Large variations in transcript levels have been observed in response to different environmental and hormonal factors such as light, abscisic acid, auxin, and salt stress (4). At the post-translational level, channel activity is controlled by intracellular factors such as H+ (5, 6) and cyclic nucleotides (7, 8). In addition, there is strong evidence that also interacting regulatory proteins, e.g. kinases and phosphatases, dynamically modify channel activity (9–15). Interestingly, the tetrameric structure of the channels provides another level of control of their functional properties. A functional channel can be formed not only by the assembly of four identical subunits (homomeric channels) but also by polypeptides encoded by different Shaker-like K+ channel genes (15–30). As in animal cells, where the diversity of voltage-gated K+ channels arises from the formation of heteromultimeric channels with properties distinct from those of their parent homomultimers (31), heteromerization could potentially yield in plant cells a large diversity of channels being distinctly sensitive to regulatory stimuli. In animal Shaker channel subunits, a domain located in the N-terminal region contributes to discriminating compatible and incompatible channel subunits (32). In contrast, in plant Shaker-like channels, such discrimination involves the cytoplasmic C terminus (22, 33–35).

In Arabidopsis, the Shaker-like K+ channel family comprises nine members, and among them, six are expressed in guard cells. Only one gene (GORK) encodes the outward-rectifying K+ conductance (36), whereas five genes (KAT1, KAT2, AKT1, AKT2, and AtKC1) encode inward-rectifying K+ channel subunits. Among these, KAT1 and KAT2 are predominantly expressed, whereas AKT2, AKT1, and AtKC1 are expressed only at lower levels (37–39). Comparison of the amino acid sequence of KAT1 and KAT2 revealed that they share an identity of 85% within the region from the first residue to the end of the putative cyclic nucleotide-binding domain. The S4 segments of both channels are identical, and the P domain of KAT2 differs from that of KAT1 only by a single residue. Yeast two-hybrid interaction tests and coexpression experiments in Xenopus oocytes have already demonstrated that KAT1 and KAT2 subunits have the potential to interact and to form heteromeric channels (19). However, it is not known whether they show any preference for homomeric or heteromeric assembly as has been reported for AtKC1 and AKT1 (27) and for KAT2 and AKT2 (20). Therefore, we investigated the features of KAT1 and KAT2 homomers and of heteromeric KAT1-KAT2 channels of defined stoichiometry and compared them with those of channels formed by unbiased assembly and with those of native inward-rectifying K+ channels in Arabidopsis guard cells. We provide evidence that, in heterologous expression systems as well as in vivo, assembly of heteromeric KAT1-KAT2 channels is favored above that of homomeric KAT1 and KAT2 channels, so the native inward conductance in Arabidopsis guard cells relies mainly on channels made of two KAT1 and two KAT2 subunits.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Biology

KAT1 and KAT2 cDNAs were modified by PCR mutagenesis to obtain three different constructs for each gene: the first by introducing a XhoI and a NdeI restriction site just upstream from the start and stop codons, respectively; the second by introducing a NdeI restriction site just upstream from the start codon and a NotI restriction site just downstream from the stop codon; and the last by introducing a XhoI restriction site just upstream from the start codon and a NotI restriction site just downstream from the stop codon. After appropriate enzymatic digestion, the modified sequences were then associated to form cDNAs encoding tandem subunits (KAT1-KAT1, KAT1-KAT2, KAT2-KAT1, and KAT2-KAT2) and were subcloned into the XhoI and NotI restriction sites of the modified transcription vector pGEMHE (a gift from D. Becker, Department of Molecular Plant Physiology and Biophysics, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany) under the control of the T7 promoter and between the noncoding 5′- and 3′-flanking regions of the Xenopus β-globin gene.

Expression in Xenopus Oocytes and Electrophysiology

In vitro transcriptions were performed using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Ultra kit (Ambion) following the manufacturer's instructions. Different capped and polyadenylated cRNA constructs were produced. Xenopus oocytes were purchased from the Centre de Recherche en Biochimie Macromoléculaire (CNRS, Montpellier, France). Stage V–VI oocytes were selected and kept in modified ND96 solution (2 mm KCl, 96 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 5 mm HEPES-NaOH, and 2.5 mm sodium pyruvate (pH 7.5)). Oocytes were injected with a final volume of 30 nl of various cRNAs using a 10–15-μm tip diameter micropipette and a pneumatic injector. Regarding co-injections, cRNA mixtures were systematically prepared at a determined concentration ratio before injection. Injected oocytes were then maintained at 19 °C for 3–5 days in modified ND96 solution. Whole-cell currents from oocytes were recorded 2–5 days after injections as described previously (40) using the two-microelectrode voltage-clamp technique. The bath solution contained, unless stated otherwise, 100 mm KCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 1.5 mm MgCl2, and 10 mm HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.5) and was continuously perfused through the chamber. For patch-clamp experiments, cell-attached patch-clamp recordings were performed on devitellinized oocytes as described previously (5, 6). Voltage-pulse protocol application, data acquisition, and data analysis were performed using pCLAMP Version 10.0 (Axon Instruments) and SigmaPlot Version 8.0. All experiments were performed at room temperature (20–21 °C). The dependence of open probability on membrane potential was derived from the I-V relationship of channel steady-state current by a previously described procedure (40).

Modeling Tetrameric Channel Assembly from Two Types of Monomers

In silico simulations were performed to predict the subunit composition of tetrameric channels assembled from a given stock of monomeric α-subunits of two types (e.g. KAT1 and KAT2). Channel formation was achieved in two steps: assembly of monomers to form dimers and then assembly of dimers to form tetramers. Both the pairing of subunits to form dimers and the subsequent pairing of dimers to form tetramers were considered to be random processes, but three different hypotheses were considered regarding the fate of the dimers between the two steps. In the first hypothesis (fully random assembly), all the formed dimers were assumed to participate in subsequent tetramer formation regardless of their subunit composition. In the second hypothesis (preference for homodimers), dimers were allowed either to dissociate or to participate in tetramer formation, but homodimers (e.g. KAT1-KAT1 and KAT2-KAT2) underwent the latter fate with a probability 10 times higher than heterodimers (KAT1-KAT2 and KAT2-KAT1). The third considered hypothesis (preference for heterodimers) was the reverse of the second one: formed heterodimers (KAT1-KAT2 and KAT2-KAT1) participated in tetramer formation with a probability 10 times higher than homodimers (KAT1-KAT1 and KAT2-KAT2). In practice, virtual drawings (i.e. in silico) were performed until exhaustion of an initial stock of 400 subunits of two types (e.g. KAT1 and KAT2), i.e. until 100 tetramers were formed. For a given monomer stock, 1000 random drawings were performed and averaged to yield a mean dimer stock (of 200 dimers) used subsequently in 1000 new random drawings to indicate the mean number of tetramers obtained for each type of the six possible combinations.

Guard Cell Protoplast Isolation and Electrophysiological Recordings

Plants were grown in compost for 5 weeks in a greenhouse. Guard cell protoplasts were enzymatically isolated from leaf abaxial epidermal peels using a digestion solution containing 1 mm CaCl2, 2 mm ascorbic acid, 1% (w/v) cellulase (“Onozuka” RS, Yakult Pharmaceutical), 0.1% (w/v) pectolyase (Y-23, Seishin Pharmaceutical), 450 mosm d-mannitol, and 1 mm MES3-KOH (pH 5.5). Epidermal peels were digested for 40 min at 27 °C. The released protoplasts were collected through a 50-μm pore diameter mesh; rinsed with solution containing 20 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, 100 mm potassium glutamate, 225 mm d-mannitol, and 10 mm MES-HCl (pH 5.5); allowed to sediment for at least 30 min; rinsed again; and then stored on ice in the same solution. Patch-clamp pipettes were pulled (P97, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) from borosilicate capillaries (Kimax-51, Kimble). The pipette solution contained 100 mm potassium glutamate, 2 mm MgATP, 5 mm EGTA, 1 mm CaCl2 (free Ca2+, 50 nm), 0.5 mm MgCl2, 300 mm d-mannitol, and 20 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.25). The bath solution had the same composition as the protoplast storage solution. Under these conditions, the pipette resistance was ≈12 megaohms. Patch-clamp recordings were performed using an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments). pCLAMP Version 9.0 (Axon Instruments) was used for voltage-pulse stimulation, data acquisition, and analysis. The voltage-clamp protocol consisted of stepping the membrane potential from a holding potential of −100 mV to −260 mV in −20-mV increments. Liquid junction potentials at the pipette/bath interface were measured and corrected off-line.

GFP Imaging

KAT1 and KAT2 cDNAs were amplified by PCR and cloned into plasmids pLoc and pFunct (41) for expression of GFP-tagged and untagged channel subunits, respectively. The resulting plasmids were introduced by cotransfection into tobacco mesophyll protoplasts (41). Protoplasts were visualized for GFP fluorescence under a Zeiss confocal microscope (LSM 510 AX70). Excitation was obtained with an HFT 488 nm beam splitter, and the emitted radiations were selected with two filters: 505/530-nm band pass for GFP and 585-nm long pass for chlorophyll.

RESULTS

Comparing Features of Channels Built of Single Subunits (KAT1 and KAT2), of Homotandems (KAT1-KAT1 and KAT2-KAT2), and of Heterotandems (KAT1-KAT2 and KAT2-KAT1)

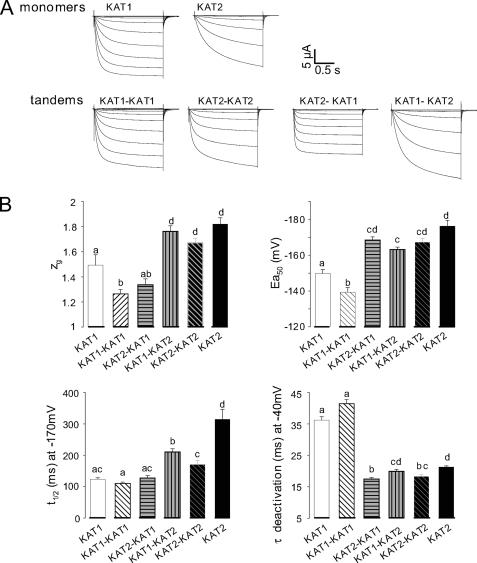

Tandem transcripts encoding fusion polypeptides, in which the C-terminal end of one channel subunit is covalently linked to the N terminus of another channel subunit, are a powerful tool to study heteromeric channels of predefined subunit composition (31, 42–44). We therefore generated KAT1-KAT1 and KAT2-KAT2 homotandems as well as KAT1-KAT2 and KAT2-KAT1 heterotandems (Fig. 1A) and expressed them in Xenopus oocytes. Homomeric tandem transcripts (KAT1-KAT1 and KAT2-KAT2) were used to check whether the covalent link between two subunits changed the channel properties in comparison with homomeric channels formed by single KAT1 or KAT2 subunits. When injected into separate oocyte subbatches, all these cRNAs yielded typical inward-rectifying K+ currents with delayed activation upon hyperpolarization below a negative voltage threshold (Fig. 2A). A first inspection of the currents indicated that KAT1 channels were activated faster than KAT2 channels regardless of whether these channels were formed by homotandems or by free subunits. Therefore, it seemed that the covalent link between subunits in tandems had little effect on channel behavior. To substantiate this conclusion, we analyzed the biophysical characteristics of the different channels. We measured the time constants for channel activation (t½) and deactivation (τ) and the single channel conductance and described the voltage-dependent gating of the channels by Boltzmann functions resulting in the typical parameters zg and Ea50 for the apparent gating charge and half-activation voltage, respectively (Fig. 2B). The above observation regarding homotandems seemed confirmed, whereas considering the studied parameters, heteromeric channels yielded by the KAT2-KAT1 or KAT1-KAT2 tandem showed characteristics similar to either KAT1 channels (zg, t½) or KAT2 channels (τ) or intermediate between KAT1 and KAT2 (Ea50). In addition, single channel conductance values for the different types of channels were very similar (Table 1). We concluded that the tandem strategy provides a mean for controlling subunit composition of tetrameric channels without unacceptable distortion of functional characteristics of the channels.

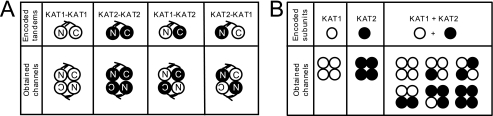

FIGURE 1.

Channel types resulting from expression of tandem or single transcripts encoding KAT1 (open circles) and KAT2 (closed circles) in oocytes. Shown is a schematic representation of various channel configurations that could be expressed in oocytes after the injection of tandem transcripts (A) or after the injection or co-injection of single transcripts encoding KAT1 or KAT2 channel α-subunits (B). N-subunits are those linked by their N-terminal end, whereas C-subunits are linked by their C terminus.

FIGURE 2.

Properties of currents recorded in oocytes injected with different cRNAs encoding single or tandem subunits. A, typical ionic currents recorded in oocytes injected with KAT1 or KAT2 cRNA or different tandem constructs (KAT1-KAT1, KAT2-KAT2, KAT2-KAT1, and KAT1-KAT2). Macroscopic currents were recorded with the voltage-clamp technique in 100 mm K+ external solution. In all recordings, the holding potential was −40 mV, and 1.7-s voltage pulses were applied to values ranging between +40 and −200 mV with −15-mV decrements. B, comparison of the functional properties of KAT1 (white bars), KAT2 (black bars), and KAT1 + KAT2 currents (gray bars). The gating parameters (zg and Ea50) were obtained from the best fit with a Boltzmann distribution of the open probability as described previously (39), and each value represents the mean ± S.E., with n = 22, 36, 25, 18, 50, and 46 oocytes expressing KAT2-KAT1, KAT1-KAT2, KAT1, KAT2, KAT1-KAT1, and KAT2-KAT2 cRNAs, respectively. t½ activation is the time for half-activation in response to a voltage step from −40 to −170 mV (mean ± S.E., with n = 16, 26, 11, 16, 31, and 42 oocytes expressing KAT2-KAT1, KAT1-KAT2, KAT1, KAT2, KAT1-KAT1, and KAT2-KAT2 cRNAs, respectively). τ deactivation is the time for half-deactivation derived by fitting decaying monoexponential functions to the tail currents (recorded on return to the holding potential; mean ± S.E., with n = 20, 30, 15, 11, 32, and 37 oocytes expressing KAT2-KAT1, KAT1-KAT2, KAT1, KAT2, KAT1-KAT1, and KAT2-KAT2 cRNAs, respectively). Two identical letters above the bars indicate no statistically different data sets (p > 0.95, Student's t test).

TABLE 1.

Channel unitary conductances

Open channel conductances were determined in the cell-attached configuration. When few channels remained active in the patch, some pulses to −110, −125, −150, and −160 mV allowed the determination of unitary currents. For each potential, the unitary current amplitudes were obtained from Gaussian fit to amplitude histograms. Unitary conductance values were obtained from linear fits to the single channel current-voltage curves within the −110 to −160 mV voltage range (data are given as means ± S.E., n = 3). Unitary conductance for KAT1 and KAT2 channels are those reported by Hoshi (7) and Pilot et al. (19), respectively. pS, picosiemens.

| Encoding transcript |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KAT1 | KAT2 | KAT1-KAT1 | KAT2-KAT2 | KAT1-KAT2 | KAT2-KAT1 | |

| pS | ||||||

| Unitary conductance | 5–6 | 6.7 | 6.2 | 6.8 | 7.4 | 7.0 |

Coexpression of KAT1 and KAT2 Subunits in Xenopus Oocytes Points to Preferences in Heteromeric Channel Assembly

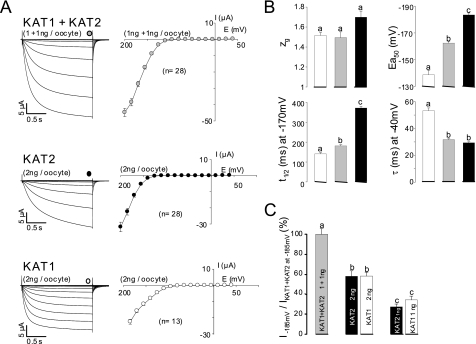

Upon coexpression of both KAT1 and KAT2 transcripts in the same batch of oocytes, it can be expected that a heterogeneous population of up to six different channel types will be formed (Fig. 1B). To assess whether actually all possible combinations are built, we injected oocytes from the same batch in parallel with either KAT1 transcripts (2 ng/oocyte) or KAT2 transcripts (2 ng/oocyte) or an equimolar mixture of both (1 ng of each/oocyte). Macroscopic currents recorded from these oocytes showed the well known features of fast activating KAT1 channels, slowly activating KAT2 channels, and intermediate KAT1-KAT2 heteromers (compare Fig. 3A with Fig. 2A). Regarding the parameters derived from the analyses of these macroscopic currents (zg, Ea50, t½, and τ), (KAT1 + KAT2)-co-injected oocytes displayed a pattern similar to that of tandem KAT1-KAT2 (or KAT2-KAT1)-injected ones. For example, the zg and t½ values were closer to those for KAT1 than to those for KAT2; the Ea50 values were intermediate between those for KAT1 and KAT2; and the τ values were closer to those for KAT2 than to those for KAT1. However, current levels (at −185 mV) in oocytes injected with 2 ng of KAT1 or KAT2 transcript were very similar to each other and about twice those in oocytes injected with 1 ng of KAT1 or KAT2 transcript (Fig. 3C). This suggested that the translation machinery of the oocytes was not saturated by these amounts of heterologous cRNAs and responded almost linearly. Coexpression of KAT1 and KAT2 produced some synergistic effect: injection of 1 ng of KAT1 + 1 ng of KAT2 yielded much larger currents compared with injection of 2 ng of any of these cRNAs (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these experiments and analyses suggest that (KAT1 + KAT2)-co-injected oocytes expressed mainly heteromeric channels with two subunits of each type. Therefore, we designed in the following experiments to evaluate our hypothesis of a preference for a 2:2 KAT1/KAT2 stoichiometry.

FIGURE 3.

Properties of currents recorded in oocytes injected with KAT1 or KAT2 or with both cRNAs. A, left panel, representative macroscopic current traces recorded with the voltage-clamp technique in a 100 mm K+ external solution from oocytes co-injected with equimolar amounts of each cRNA (1 ng each) or injected with 2 ng of either KAT2 or KAT1 cRNA. In all recordings, the holding potential was −40 mV, and voltage steps were applied to potentials ranging between +40 and −200 mV with −15-mV decrements. Right panel, steady-state current-voltage relationships. Total current (I; sampled at the times indicated by symbols over the traces) is plotted against the membrane potential. Data are means ± S.E. (with the number of oocytes indicated in parentheses). B, comparison of the functional properties of KAT1 (white bars), KAT2 (black bars), and KAT1 + KAT2 (gray bars) currents. Gating and kinetic parameters were determined in 100 mm K+ external solution. Each value represents the mean ± S.E. (n ≥ 8 oocytes). C, measurement of current intensities from oocytes injected with KAT1 or KAT2 or with both cRNAs. All current values were sampled at the end of a hyperpolarizing pulse of 1.7 s at −185 mV. Results are displayed as means ± S.E., with n = 28, 10, 28, 13, and 10 oocytes injected with KAT1 + KAT2 (1 ng each), KAT1 (2 ng), KAT2 (2 ng), KAT1 (1 ng), and KAT2 (1 ng) cRNAs, respectively. The current values were normalized with respect to the mean of currents recorded at −185 mV in oocytes co-injected with KAT1 + KAT2 cRNAs (1 ng each). The letters above each bar represent the results of a Student's t test; two identical letters indicate two corresponding results that are not statistically different (p > 0.95).

The “Preference for Heterodimers” Hypothesis Best Fits the Data

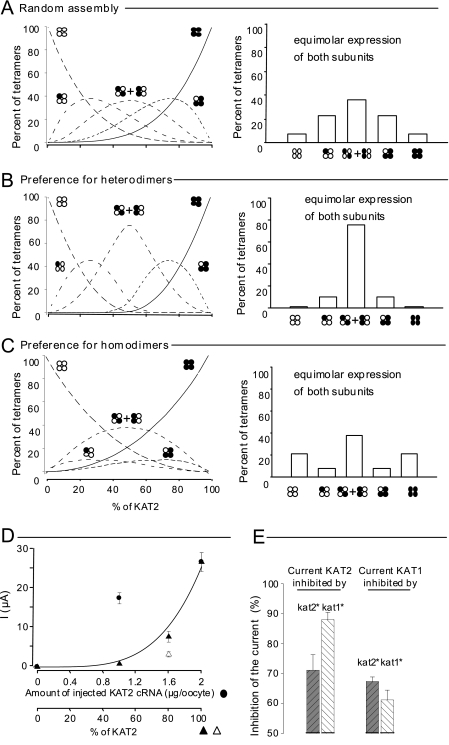

As diagramed in Fig. 1, coexpression of KAT1 and KAT2 subunits is expected to result in up to six types of channels. It has been reported previously that couples of plant Shaker-like subunits such as AtKC1 and AKT1 (15, 27) or KAT2 and AKT2 (20) would form heteromeric channels preferably to homomeric ones. It has been proposed that this results from a preference for heterodimers over homodimers after the first step of channel assembly. Here, in-line with these former data, three hypotheses were considered regarding channel assembly from expressed pools of KAT1 and KAT2 subunits (see details under “Experimental Procedures”). In this framework, the distribution of expressed channels between the six possible subunit combinations shown in Fig. 1 could be predicted in silico as a function of relative KAT2 expression defined as the percent of KAT2 in the total (KAT2 + KAT1) subunit pool. Thereby, in any of the three considered hypotheses, the fraction of homotetrameric KAT2 channels varies from 0% (i.e. only KAT1 is expressed) to 100% (i.e. only KAT2 is expressed). The formation frequency of homotetramers is then a function of the KAT2/(KAT2 + KAT1) ratio and depends on the hypothesis regarding the dimerization process (Fig. 4, compare A–C). At any KAT2/(KAT2 + KAT1) ratio, the frequency of homotetramers is the highest if homodimers are preferred and the lowest if heterodimers are preferred.

FIGURE 4.

KAT1 and KAT2 subunit interactions computer-modeled and revealed by a dominant-negative approach in Xenopus oocytes. A–C, in silico prediction of the percentage of different tetramers formed in oocytes from a given stock of KAT1 (white circles) and KAT2 (black circles) subunits. Three hypotheses were considered (see details under “Experimental Procedures”): random assembly (A), preference for heterodimers (B), and preference for homodimers (C). Six types of tetramers (indicated by clusters of four white or black circles; see Fig. 1B) were expected to assemble from the initial stock of single subunits. Left panels, distribution of the assembled tetramers in the six possible combinations (expressed as percent, y axis) as a function of the proportion of KAT2 in the initial stock of subunits (expressed as percent, x axis). Right panels, bar graph representations of the same tetramer distribution in the particular case of equimolar expression of KAT1 and KAT2 subunits (50% abscissa in left panels, corresponding to the situation expected in the upper part of A and in Fig. 3, B and C). D, two-electrode voltage-clamp recordings made on oocytes bathed with a 100 mm K+ external solution. Data represent current values sampled at the end of a hyperpolarizing pulse of 1.7 s to −185 mV. Currents were recorded in oocytes injected with different amounts of wild-type KAT2 cRNA (black circles; the dotted line represents a linear regression adjusted to these points) or co-injected with wild-type KAT2 cRNA mixed with either dominant-negative kat2* cRNA (black triangles) or dominant-negative kat1* cRNA (white triangle). The dominant-negative mutation (*) is in the selectivity filter GYGD → RRGD (not functional) (20). The solid line represents the theoretical increase in the macroscopic current when the molar ratio of wild-type KAT2 subunits increases and when the association between wild-type and dominant-negative subunits is achieved randomly (from A; fits well with the KAT2 + kat2* data (black triangles) but not the KAT2 + kat1* data (white triangle)). E, KAT2 (left) and KAT1 (right) current inhibition by dominant-negative kat1* (white bars) and kat2* (black bars) subunits. All oocytes were co-injected with 1.6 ng of wild-type cRNA (KAT1 or KAT2) and 0.4 ng of mutant cRNA (kat1* or kat2*). Current values were sampled at the end of a hyperpolarizing pulse of 1.7 s to −185 mV and were normalized by the KAT2 (or KAT1) currents recorded at −185 mV in oocytes injected with 2 ng of KAT2 (or KAT1) cRNA. Results are displayed as means ± S.E. (n = 6).

Regarding the four types of possible heteromeric channels, at an equimolar ratio of KAT1 and KAT2 subunits (50% KAT2) (Fig. 4, A–C, right panels, corresponding to experimental conditions tested in Fig. 3A, right panel), channels with two subunits of each type were most abundant only if heterodimers were preferred. They represented almost 80% of the expressed channels in this case (Fig. 4B) and only 40% in the case of random assembly (Fig. 4A) or preference for homodimers (Fig. 4C).

Cross-inhibition of KAT2 Current by Dominant-negative KAT1 Subunits (and the Reverse) Suggests Preferential Heteromerization

If one considers that the white symbols shown in Fig. 4 (A–C) represent dominant-negative subunits (i.e. kat2* or kat1*) (20) instead of wild-type KAT1 or KAT2 subunits, the same curves should represent the frequency of any type of channels resulting from the coexpression of KAT2 and kat2* (or KAT2 and kat1*). In any of these two cases, however, only homomeric KAT2 channels (i.e. channels with neither kat1* nor kat2* subunit) should be able to catalyze currents. Macroscopic current value plotted as a function of the KAT2 ratio should fit, in the case of KAT2 and kat2* coexpression, the tetrameric KAT2 kinetics in Fig. 4A because dimer formation from these subunits is expected to be a strictly random event. This was actually checked (Fig. 4D, black triangles and solid curve), as was the essentially linear increase in current expected upon increase of the injected amount of KAT2 transcript in the 0–2 ng/oocyte range (Fig. 4D, black circles and dotted line). If kat1* (instead of kat2*) was coexpressed with KAT2, the macroscopic current at 80% KAT2 was less than that for kat2* coexpression (compare white and black triangles). Based on the relative disposition of KAT2 channel curves in Fig. 4 (A–C), this suggests that KAT2-kat1* dimers would be preferred to KAT2-KAT2 dimers. In fact, both the greater inhibition of KAT2 current by kat1* than by kat2* and the greater inhibition of KAT1 current by kat2* than by kat1* (Fig. 4E) suggest a preference for heterodimerization between KAT1 and KAT2 subunits.

Native Inward K+ Conductances in Guard Cells from Different Arabidopsis Genotypes Suggest the Preferential Heteromerization of KAT1 and KAT2 Subunits in Planta

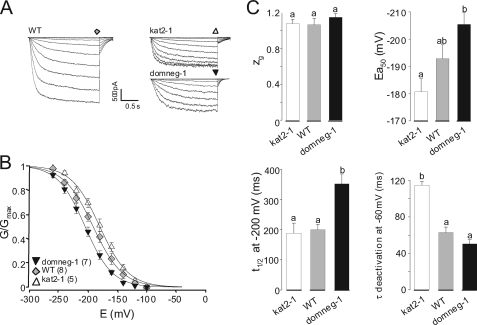

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed on guard cell protoplasts obtained from three different Arabidopsis genotypes (26): wild-type, kat2-1 (knock-out mutant, carrying a T-DNA insertion in the KAT2 gene), and domneg-1 (expressing the kat2* polypeptide (dominant-negative) in a wild-type background). All three genotypes displayed time- and voltage-dependent inward K+ currents at the guard cell membrane level (Fig. 5A). Currents recorded in protoplasts from mutant plants were, however, of smaller amplitude than those in wild-type protoplasts. The three gating curves (G/Gmax plotted against voltage) were significantly different (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, with respect to the four parameters investigated previously in oocytes (Fig. 3), the wild-type, kat2-1, and domneg-1 protoplasts ranged similarly to (KAT1 + KAT2)-, KAT1-, and KAT2-expressing oocytes, respectively (Figs. 3B and 5C, compare bar graphs).

FIGURE 5.

K+ conductances in guard cells from wild-type and mutant plants. A, representative macroscopic current traces recorded with the patch-clamp technique on guard cell protoplasts from wild-type (WT), kat2-1 (knock-out mutant disrupted in the KAT2 gene), or domneg-1 (expressing a dominant-negative kat2* construct in the wild-type background) plants. In all recordings, the holding potential was −100 mV. The membrane potential was clamped from −100 to −260 mV with −20-mV decrements. B, comparison of the gating properties of the inward K+ conductance in the different genotypes. G/Gmax data are displayed as means ± S.E. (with the number of repeats in parentheses). Solid lines are Boltzmann fits performed on mean data from each genotype. C, gating and kinetic parameters characterizing guard cell inward K+ conductance in each genotype. Boltzmann parameters (the equivalent gating charge, zg, and the half-activation potential, Ea50) result from the fits displayed in B; t½ activation is the time for half-activation in response to a voltage step from a holding potential of −100 mV to −200 mV; and τ deactivation is derived by fitting the tail currents with decaying monoexponential functions (recorded upon return to −60 mV). Results are means ± S.E., with n = 8, 5, and 7 for zg and Ea50; n = 11, 7, and 4 for t½; and n = 8, 3, and 3 for τ for the wild-type, kat2-1, and domneg-1 genotypes, respectively). Letters above each bar represent the results of a Student's t test; two identical letters indicate results that are not statistically different (p > 0.95).

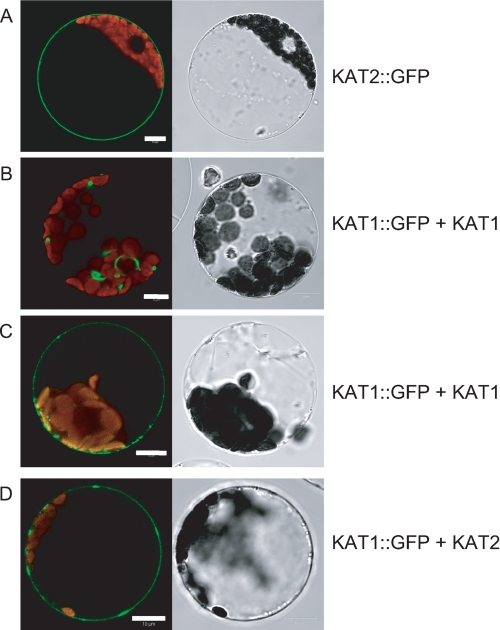

KAT2 Effect on KAT1 Subcellular Localization

KAT2-GFP has been demonstrated to be localized to the plasma membrane (20). When expressed alone (data not shown) or with untagged KAT1 (Fig. 6, B and C), KAT1-GFP remained mainly intracellular in aggregates around the nucleus, suggesting localization in the endoplasmic reticulum (observed in 50% of the protoplasts showing fluorescence) (Fig. 6B). However, also in the plasma membrane, a few fluorescent patches could be detected (observed in the remaining 50% of the protoplasts) (Fig. 6C). Such a subcellular localization for KAT1 has already been reported (45, 46). However, coexpression of KAT1-GFP with KAT2 resulted in a shift in the fluorescence to the plasma membrane (Fig. 6D) that was detected in 90% of the protoplasts. (The remaining 10% probably do not express both subunits.)

FIGURE 6.

Subcellular localization of KAT1-GFP in tobacco mesophyll protoplasts. A, protoplasts expressing KAT2-GFP alone (representative of 100% of GFP-stained protoplasts). B and C, protoplasts coexpressing KAT1-GFP and KAT1 (each representative of 50% of GFP-stained protoplasts). D, protoplasts coexpressing KAT1-GFP and KAT2 (representative of 90% of GFP-stained protoplasts). Left panels, protoplast sections analyzed for GFP fluorescence by confocal imaging; right panels, corresponding pictures obtained with transmitted light.

DISCUSSION

Evaluation of the Tandem Strategy

Biochemical analyses of Shaker channels purified from AKT1-transfected insect cells have revealed that only monomers, dimers, and tetramers can be isolated (no trimers), suggesting that plant Shaker channels, as their animal counterparts, did not result from stepwise sequential addition of monomers but rather from dimerization of dimers (35). Dimeric tandems made of two covalently linked subunits of plant Shaker channels have previously been used to address the role of the KDC1 subunit expressed in carrot, which is unable to form homomeric functional channels but can participate in heteromeric ones (21, 23, 47). In theory, use of tandem constructs allows the study of channel population with determined composition. Actually, forced dimerization of subunits can affect biophysical properties of channels (48). For this reason, the tandem strategy must be used cautiously.

First, we checked that both subunits in a tandem do participate in the formation of the tetrameric channel. This was done by constructing tandem cRNA encoding a wild-type subunit linked to a dominant-negative one (KAT2-kat2* for example) and injecting them in oocytes. If only one-half of such tandems would participate in the formed channels, then one-sixteenth of the channels obtained would include four wild-type subunits and catalyze currents. Actually, none of the tested constructs allowed currents to be recorded, even when large amounts of cRNA had been injected into oocytes (data not shown). This did not result from an unsuccessful expression of these constructs because they did inhibit currents catalyzed by their corresponding wild-type tandem (supplemental Fig. S2). Thus, it should be accepted that both halves of the tandems are involved in the formation of the same channel.

Second, the “linking effect” on channel properties was studied by comparing the functional properties of oocytes injected with wild-type homotandems and wild-type monomers. Despite the same subunit composition, channels differed slightly in voltage-dependent gating and kinetic parameters (Fig. 2B). Within channels made of KAT1-KAT1 or KAT2-KAT2 tandems, N and C termini are probably unable to interact with other parts of the channel as if they were not covalently linked. This is likely to influence channel voltage-dependent gating kinetics as has been reported for KAT1 (49, 50). Nevertheless, despite the slight distortion introduced by forced dimerization, the effect is small (Fig. 2B), and the use of the tandem strategy seems to be appropriate to obtain insights into the biophysical properties of heteromeric channels made of two KAT1 and two KAT2 subunits. Different linker lengths (from 2 to 20 amino acids) were used in previous studies to associate two Shaker or CNGC subunits in tandem (31, 42, 43, 51). Because the use of a short linker in a dimeric KAT1 construct has already been reported to not affect the biophysical properties of KAT1 channels (23, 47), the same strategy was used to generate all the tandems used. Our results demonstrate that our strategy could be used to study heteromerization between KAT1 and KAT2.

Preferential Heteromerization of KAT1 and KAT2

The coexpression of KAT1 and KAT2 subunits yielded macroscopic currents endowed with properties very similar to those of currents resulting from expression of KAT1-KAT2 (or KAT2-KAT1) tandems (Figs. 3B and 2B, respectively). As shown by in silico simulations, this suggested that, among the six possible tetrameric combinations (Fig. 1B), the 2KAT1–2KAT2 channel is preferentially expressed because heteromeric dimers are more stable (or more likely to be formed) than homomeric ones. Preferential KAT1-KAT2 heteromerization is further suggested by the fact that the kat1* (dominant-negative) mutant subunit inhibits KAT2 current more than the kat2* mutant subunit (Fig. 4E).

Preferential heteromerization has already been reported for AKT2 and KAT2 coexpressed in Xenopus oocytes (20) and for AKT1 and AtKC1 coexpressed in tobacco protoplasts (27). Here, a third example of preferential heteromerization is documented. The fact that KAT1 and KAT2 are both expressed in guard cells does strengthen the physiological significance of this preferential heteromerization, and therefore, the resulting functional properties become worth studying.

Functional Consequences of KAT1-KAT2 Heteromerization

Whether they resulted from tandem expression (Fig. 2) or from KAT1 and KAT2 coexpression (Fig. 3), heteromeric KAT1-KAT2 channels have seemingly inherited kinetics from the faster subunit type. This can be explained as follows. Starting from the closed state, conformational transitions for each subunit have to occur before a Shaker channel opens. Positive cooperativity among subunits has been shown during voltage-dependent activation of Shaker channels: any subunit undergoing first transition toward the active conformation drives the others to do so (52–54). In this context, it is not surprising to observe that KAT1 subunits (faster activation/lower t½ in homomeric channels) pass their t½ on the heteromeric KAT1-KAT2 channels. A reciprocal rationale holds for deactivation of heteromeric channels. Upon voltage-dependent deactivation, that a single subunit leaves the open state conformation is enough to close the channel (55, 56). It is then logical to observe that KAT2 subunits (faster deactivation/lower τ in homomeric channels) pass their τ on the heteromeric KAT1-KAT2 channels.

KAT1-KAT2 Synergy

Some synergistic effect of KAT1 and KAT2 coexpression was observed as evidenced by currents larger than those after expression of KAT1 or KAT2 alone (Fig. 3, A and C). Individual properties of heteromeric KAT1-KAT2 channels may hardly explain this finding (Fig. 2B and Table 1). Thus, this synergistic effect could rather rely on the number of channels found at the membrane, e.g. on channel trafficking. In plant cells, the KAT1 channel has been demonstrated to be located mainly in intracellular membranes (41, 45, 46), whereas in transiently transformed tobacco protoplasts, it has been shown that KAT2-GFP is fully localized to the cell membrane (20). As demonstrated for the pair AKT2::GFP + KAT2 (20), upon coexpression of KAT1::GFP with KAT2, most of the fluorescence is found at the cell membrane, indicating that KAT2 is able to increase the traffic of KAT1::GFP to the cell membrane through interactions within heteromeric KAT2 + KAT1::GFP channels (Fig. 6). This helper role of KAT2 regarding KAT1 explains the KAT1-KAT2 synergistic effect. Finally, the currents in protoplasts from wild-type plants are much larger than those from mutant plants, suggesting that the synergistic effect of KAT1 and KAT2 coexpression takes place in Arabidopsis guard cells.

Physiological Relevance of KAT1-KAT2 Heteromerization

When recorded on guard cell protoplasts prepared from kat2-1, domneg-1, and wild-type plants using the patch-clamp technique, macroscopic inward K+ currents displayed functional characteristics reminiscent of those recorded in Xenopus oocytes expressing KAT1, KAT2, and KAT1 + KAT2, respectively. In guard cells deprived of KAT2 (kat2-1 genotype), the dominantly expressed subunit was likely to be KAT1, and macroscopic currents would be catalyzed mainly by KAT1 channels. Data obtained in the two other genotypes bear evidence of in vivo preferential heteromerization for two reasons. First, currents recorded in domneg-1 protoplasts were similar to KAT2 currents in oocytes, suggesting a preferential association of kat2* subunits with KAT1 ones in guard cells (similar to oocyte data displayed in Fig. 3C), allowing homomeric KAT2 channels to dominate the inward K+ conductance in these protoplasts. Second, K+ currents recorded in wild-type protoplasts displayed gating and kinetic parameters similar to those in oocytes expressing both KAT1 and KAT2 or the KAT1-KAT2 tandem, suggesting that, as in the heterologous context, KAT1 and KAT2 subunits tend to form preferentially heteromeric channels in Arabidopsis guard cells. Furthermore, the fact that the activation curve of the guard cell membrane potassium currents was shifted toward more negative membrane potentials in the domneg-1 mutant and toward more positive potentials in the kat2-1 mutant compared with the activation curve of the wild-type plants (Fig. 5B) indicates that heteromeric channels associating KAT2 subunits with other Shaker subunits are more frequently formed than homotetrameric KAT2 channels. Indeed, expression of the kat2 dominant-negative construct would otherwise have qualitatively the same effect on the activation curve as KAT2 disruption.

In summary, these results corroborate the observation in oocytes, indicating that, in the native system, KAT1 and KAT2 subunits interact preferably with each other to form heteromeric channels. Up to now, the experiments done on transpirational water loss in kat2-1 and domneg-1 plants did not allow the demonstration of phenotypical differences between these mutants and wild-type plants (25, 26). Similar results were obtained with kat1-1 plants (37) and kat1-domneg plants (57). Under the conditions used in these experiments, it is likely that the inward potassium current level is not sufficiently affected, quantitatively and/or qualitatively, to display a macroscopic phenotype. The above-cited genotypes should be challenged by different environmental conditions to fully understand the physiological relevance of the present data.

Conclusions

Voltage-clamp recordings on protoplasts from Arabidopsis guard cells suggest that the inward K+ conductance is dominated by heteromeric KAT1-KAT2 channels. The relative level of expression of KAT1 and KAT2 should be studied under different conditions to understand completely the role of this preferential heteromerization in guard cells. Fine-tuning of K+ channel gating kinetics, namely by combining slightly different subunit types like KAT1 and KAT2 in heteromeric channels, could be in relation to the fact that voltage-gated channels expressed in guard cells are likely to be involved not only in net and long-term exchanges of solutes (here, K+ influx) but also in the control of membrane potential (steady polarization and electrical signaling) during stomatal movements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Cécile Fizames for in silico drawings.

This work was supported in part by doctoral fellowship grants from the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique/Région Languedoc-Roussillon (to A. L.) and CNRS (to F. P.), a Heisenberg fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to I. D.), Agence National de la Recherche Génoplante Grant GPLA06041G (to B. L. and J.-B. T.), and Agropolis Foundation Grant 0803-022 (to J.-B. T.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- MES

- 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lebaudy A., Véry A. A., Sentenac H. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581, 2357–2366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward J. M., Mäser P., Schroeder J. I. (2009) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 71, 59–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreyer I., Blatt M. R. (2009) Trends Plant Sci. 14, 383–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Véry A. A., Sentenac H. (2003) Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54, 575–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacombe B., Pilot G., Gaymard F., Sentenac H., Thibaud J. B. (2000) FEBS Lett. 466, 351–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacombe B., Pilot G., Michard E., Gaymard F., Sentenac H., Thibaud J. B. (2000) Plant Cell 12, 837–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoshi T. (1995) J. Gen. Physiol. 105, 309–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaymard F., Cerutti M., Horeau C., Lemaillet G., Urbach S., Ravallec M., Devauchelle G., Sentenac H., Thibaud J. B. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 22863–22870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michard E., Dreyer I., Lacombe B., Sentenac H., Thibaud J. B. (2005) Plant J. 44, 783–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michard E., Lacombe B., Porée F., Mueller-Roeber B., Sentenac H., Thibaud J. B., Dreyer I. (2005) J. Gen. Physiol. 126, 605–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu J., Li H. D., Chen L. Q., Wang Y., Liu L. L., He L., Wu W. H. (2006) Cell 125, 1347–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li L., Kim B. G., Cheong Y. H., Pandey G. K., Luan S. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 12625–12630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luan S. (2009) Trends Plant Sci. 14, 37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luan S., Lan W., Chul Lee S. (2009) Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12, 339–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geiger D., Becker D., Vosloh D., Gambale F., Palme K., Rehers M., Anschuetz U., Dreyer I., Kudla J., Hedrich R. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 21288–21295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dreyer I., Antunes S., Hoshi T., Müller-Röber B., Palme K., Pongs O., Reintanz B., Hedrich R. (1997) Biophys. J. 72, 2143–2150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baizabal-Aguirre V. M., Clemens S., Uozumi N., Schroeder J. I. (1999) J. Membr. Biol. 167, 119–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ache P., Becker D., Deeken R., Dreyer I., Weber H., Fromm J., Hedrich R. (2001) Plant J. 27, 571–580 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pilot G., Lacombe B., Gaymard F., Chérel I., Boucherez J., Thibaud J. B., Sentenac H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 3215–3221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xicluna J., Lacombe B., Dreyer I., Alcon C., Jeanguenin L., Sentenac H., Thibaud J. B., Chérel I. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 486–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naso A., Dreyer I., Pedemonte L., Testa I., Gomez-Porras J. L., Usai C., Mueller-Rueber B., Diaspro A., Gambale F., Picco C. (2009) Biophys. J. 96, 4063–4074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dreyer I., Porée F., Schneider A., Mittelstädt J., Bertl A., Sentenac H., Thibaud J. B., Mueller-Roeber B. (2004) Biophys. J. 87, 858–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naso A., Montisci R., Gambale F., Picco C. (2006) Biophys. J. 91, 3673–3683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Formentin E., Varotto S., Costa A., Downey P., Bregante M., Naso A., Picco C., Gambale F., Lo Schiavo F. (2004) FEBS Lett. 573, 61–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lebaudy A., Hosy E., Simonneau T., Sentenac H., Thibaud J. B., Dreyer I. (2008) Plant J. 54, 1076–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lebaudy A., Vavasseur A., Hosy E., Dreyer I., Leonhardt N., Thibaud J. B., Véry A. A., Simonneau T., Sentenac H. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 5271–5276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duby G., Hosy E., Fizames C., Alcon C., Costa A., Sentenac H., Thibaud J. B. (2008) Plant J. 53, 115–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeanguenin L., Lebaudy A., Xicluna J., Alcon C., Hosy E., Duby G., Michard E., Lacombe B., Dreyer I., Thibaud J. B. (2008) Plant Signal. Behav. 3, 622–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reintanz B., Szyroki A., Ivashikina N., Ache P., Godde M., Becker D., Palme K., Hedrich R. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 4079–4084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bregante M., Yang Y., Formentin E., Carpaneto A., Schroeder J. I., Gambale F., Lo Schiavo F., Costa A. (2008) Plant Mol. Biol. 66, 61–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Isacoff E. Y., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. (1990) Nature 345, 530–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu J., Yu W., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y., Li M. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 24761–24768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daram P., Urbach S., Gaymard F., Sentenac H., Chérel I. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 3455–3463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ehrhardt T., Zimmermann S., Müller-Röber B. (1997) FEBS Lett. 409, 166–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urbach S., Chérel I., Sentenac H., Gaymard F. (2000) Plant J. 23, 527–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosy E., Vavasseur A., Mouline K., Dreyer I., Gaymard F., Porée F., Boucherez J., Lebaudy A., Bouchez D., Véry A. A., Simonneau T., Thibaud J. B., Sentenac H. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 5549–5554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szyroki A., Ivashikina N., Dietrich P., Roelfsema M. R., Ache P., Reintanz B., Deeken R., Godde M., Felle H., Steinmeyer R., Palme K., Hedrich R. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 2917–2921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ivashikina N., Deeken R., Fischer S., Ache P., Hedrich R. (2005) J. Gen. Physiol. 125, 483–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leonhardt N., Kwak J. M., Robert N., Waner D., Leonhardt G., Schroeder J. I. (2004) Plant Cell 16, 596–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lacombe B., Thibaud J. B. (1998) J. Membr. Biol. 166, 91–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hosy E., Duby G., Véry A. A., Costa A., Sentenac H., Thibaud J. B. (2005) Plant Methods 1, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gordon S. E., Zagotta W. N. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 10222–10226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heginbotham L., MacKinnon R. (1992) Neuron 8, 483–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu D. T., Tibbs G. R., Siegelbaum S. A. (1996) Neuron 16, 983–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sutter J. U., Campanoni P., Tyrrell M., Blatt M. R. (2006) Plant Cell 18, 935–954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mikosch M., Hurst A. C., Hertel B., Homann U. (2006) Plant Physiol. 142, 923–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Picco C., Bregante M., Naso A., Gavazzo P., Costa A., Formentin E., Downey P., Lo Schiavo F., Gambale F. (2004) Biophys. J. 86, 224–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCormack K., Lin L., Iverson L. E., Tanouye M. A., Sigworth F. J. (1992) Biophys. J. 63, 1406–1411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marten I., Hoshi T. (1998) Biophys. J. 74, 2953–2962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marten I., Hoshi T. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 3448–3453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pascual J. M., Shieh C. C., Kirsch G. E., Brown A. M. (1995) Neuron 14, 1055–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoshi T., Zagotta W. N., Aldrich R. W. (1994) J. Gen. Physiol. 103, 249–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith-Maxwell C. J., Ledwell J. L., Aldrich R. W. (1998) J. Gen. Physiol. 111, 399–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith-Maxwell C. J., Ledwell J. L., Aldrich R. W. (1998) J. Gen. Physiol. 111, 421–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zagotta W. N., Hoshi T., Aldrich R. W. (1994) J. Gen. Physiol. 103, 321–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zagotta W. N., Hoshi T., Dittman J., Aldrich R. W. (1994) J. Gen. Physiol. 103, 279–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kwak J. M., Murata Y., Baizabal-Aguirre V. M., Merrill J., Wang M., Kemper A., Hawke S. D., Tallman G., Schroeder J. I. (2001) Plant Physiol. 127, 473–485 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.