Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the cellular immune profile and the expression of IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α in tissue biopsies of pyostomatitis vegetans (PV). Working hypothesis was that knowledge of the cellular immune profile and role of mediators such as IL-6, IL-8 AND TNF-alpha may contribute to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of this rare entity. Archival tissues from three patients with clinically and histologically confirmed PV were studied. Analysis of the immune profile of the cellular infiltrate and expression of IL-6 and IL-8 were evaluated by immunohistochemistry. ISH was performed to evaluate the expression of TNF-α. Biopsy tissues from erythema multiforme, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, lichen planus and normal buccal mucosa were analyzed as controls. All patients were affected by multiple mucosal ulcerations and yellow pustules mainly located in the vestibular, gingival and palatal mucosa. Histopathologically, all specimens showed ulcerated epithelium with characteristic intraepithelial and/or subepithelial microabscesses containing abundant eosinophils plus a mixed infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils. Cellular immune profile of the inflammatory infiltrate revealed a predominance of T-lymphocytes, mainly of cytotoxic (CD3+/CD8+) phenotype, over B-cells. CD20+ B-lymphocytes were also identified to a lesser degree among the lymphoid cells present in the lamina propria. Overexpression of IL-6 and TNF-α was found in both epithelial and inflammatory mononuclear cells. IL-8 expression was shown in the mononuclear cells scattered among the inflammatory infiltrate. Similar findings of overexpression of IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α were, however, found in control tissues. In PV lesions, the inflammatory infiltrate shows a predominance of cytotoxic lymphocytes. Expression of IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α, although not specific to PV, appears up-regulated thus these cytokines would represent a suitable therapeutic target. However, the complexity of the cytokine network and their numerous functions require further studies in order to confirm our findings.

Keywords: Pyostomatitis vegetans, Oro-facial granulomatosis, Inflammatory bowel diseases, Pyoderma gangrenosum, T-lymphocytes, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α

Introduction

Pyostomatitis vegetans (PV) is a rare non-infectious oral disease often co-existing with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) [1–5]. PV was first described by Hallopeau in 1898 under the term of “pyodermite vegetante” and later in 1949 by McCarthy who coined the term “pyostomatitis vegetans” (reviewed in Hegarty et al. [5]). Today these two entities are considered part of the spectrum of the same disease termed “pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans” and it is rare for them to be seen in the absence of IBD [4, 6–8]. Several authors, mainly in the dermatology field, consider PV to belong to the spectrum of pyoderma gangrenosum, a skin condition observed in association with IBD, vasculitis, rheumatoid arthritis and malignant hematologic diseases [9, 10].

About 50 cases of PV have been reported in the literature. Reported age ranges from 5 to 70 years with preference for young and middle-aged individuals with a male to female ratio of 3:1. The majority of reported patients are Caucasian [5]. Clinically, PV is characterized by multiple grey to yellow pustules which progress into oral mucosal erosions forming shallow “snail-track” ulcers. Most commonly affected sites are labial and vestibular mucosa, hard and soft palate and gingiva. When lesions are present on the oral labial folds they may acquire a verrucous appearance [2]. Burning and pain may be present [5].

Histopathologic appearance includes intra- and subepithelial abscesses containing numerous eosinophils and neutrophils. There may be hyperkeratosis and acanthosis and areas of acantholysis. The underlying connective tissues contain dense lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates [1, 2, 5].

Very little is known about the etiology of PV and its pathogenic interaction with IBD. The strict association of PV with IBD (it is considered a clinical marker of ulcerative colitis) and its histologic features speak in favour of an immunological component to PV that shares pathogenetic similarities with IBD [7, 8]. Also an abnormal immunologic response to a superimposition of bacterial infection or other unknown agents may play a pathogenetic role as it has been described for IBD [11].

New data gained over the last few years have brought novel insights about the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory diseases such as the regulation and the recruitment of white cells in skin and mucosal diseases. Important immune cells, such as dendritic cells, keratinocytes, T lymphocytes, plasma cells, monocytes/macrophages and granulocytes, and a vast array of cytokines and chemokines play a pivotal immunopathogenetic role [12–16]. In the case of PV it seems reasonable to speculate that lymphocyte antigen stimulation takes place in the oral mucosa with subsequent clonal proliferation in lymph nodes and recirculation to the oral mucosa with cytokine release and recruitment of neutrophils. The predominance of neutrophils and eosinophils in the infiltrate of established lesions of PV suggests that enhanced chemotaxis or reactivity of neutrophils is the basic pathologic problem [15].

The aims of this study were to examine the cellular immune profile and expression of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α of PV samples in order to explore some of the pathogenetic events at the tissue level. The working hypothesis was that knowledge of the cellular immune profile and role of mediators such as IL-6, IL-8 AND TNF-alpha may contribute to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of this rare entity.

Materials and Methods

Selection of Patients

Two men (age 16 and 60) and one woman (age 40) with clinically and histologically confirmed PV were retrospectively identified from the files of Reference Center for the Study of Oral Diseases—University Hospital of Careggi, Florence, Italy. In two patients PV was associated with ulcerative colitis and in one patient with Crohn disease (Table 1). In addition, biopsy tissues from one case each of erythema multiforme (EM), recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS), lichen planus (LP) and normal buccal mucosa were analyzed as controls. Patients with PV and controls were all caucasian. The diagnoses of EM, RAS and LP were all confirmed clinically and histologically. These samples were chosen as control tissues because of the similarity of the inflammatory infiltrate with that of PV. Control samples were selected from patients not affected by IBD. At the time of biopsy both PV and control patients were not under immunosuppressive treatment.

Table 1.

Cellular immune profile and IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α expression in three cases of PV

| Patient | Patients’ characteristics (Age/sex/assoc. disease) | CD3 | CD4 | CD8 | CD20 | CD79a | IL-6 | IL-8 | TNF-α | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC | EC | IC | EC | IC | EC | IC | EC | IC | EC | IC | EC | IC | EC | IC | EC | ||

| 1 | 60/M/UC | +++ | +a | − | − | ++ | +a | ++ | − | ++ | − | +++ | ++ | +++ | +a | +++ | + |

| 2 | 16/M/CD | +++ | +a | − | − | ++ | +a | + | − | − | − | ++ | + | ++ | − | ++ | + |

| 3 | 40/F/UC | +++ | +a | − | − | +++ | ++a | +++ | +a | + | − | ++ | + | +++ | − | +++ | + |

Score system: +++, more than 51% of positive cells; ++, 21–50% of positive cells; +, 1–20% of positive cells; −, negative

M male, F Female, UC ulcerative colitis, CD Crohn disease, IC inflammatory cells, EC epithelial cell

aPositivity limited to intraepithelial inflammatory cells

Immunohistochemistry

Five micron thick sections were cut from tissue blocks of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. All sections were deparaffinized in Bio-Clear (Bio Optica, Milan, Italy) and dehydrated using graded ethanol. To block endogenous peroxidase activity, the slides were treated with 3.0% hydrogen peroxidase in distilled water for 10 min. For the analysis of the immune profile of the cellular infiltrate, a representative section for each lesion was selected. As primary antibody we used the following commercial antibodies: polyclonal anti-CD3, mouse monoclonal anti-CD8, confirm™anti-CD20 (clone L26), mouse monoclonal anti-CD79a (clone JCB117) (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) and anti-CD4 (clone1F6, Diapath, Italy). All tissue sections then were placed on the Ventana automated stainer BenchMark XT™ ICH system where they were deparaffinized, rehydrated and processed for blocking the endogenous peroxidase and epitope retrieval. Consecutively, using the Ventana staining procedure, the primary antibodies were placed on the tissue sections and incubated for 32 min at 37°C using as revelation system the iVIEW DAB Detection Kit. After the staining run was complete, the tissue sections were removed from the stainer, counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted with Permount. A negative control sample was included with each run by omitting the primary antibody which yielded no signal. Tonsil tissue was used as positive control. The control sections were treated in parallel with the samples and in the same run. Additional sections from the same tissue blocks were deparaffinized in Bio-Clear (Bio-Optica, Milan, Italy), hydrated with grade ethanol concentration until distilled water, and placed in 3% hydrogen peroxide/H2O2 for blocking endogenous peroxidase. Antigen retrieval was obtained by microwave pretreatment in EDTA pH 8.0 which was followed by incubation with the monoclonal antibody anti IL-8 (dilution 1:100) and rabbit polyclonal anti IL-6 (dilution 1:100). Bound antibody was evaluated using streptavidin–biotin-peroxidase complex technique and 3,3′diaminobenzidine (DAB liquid, DAKO) as chromogen. The sections were lightly counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. Immunohistochemical specimens were graded semi-quantitatively under a light-field microscope at 100× magnification. The score system was as follows: +++, more than 51% positive cells; ++, 21–50% positive cells; +, 1–20% positive cells; −, negative.

In situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization (ISH) was done to evaluate the expression of TNF-α. Five micron thick sections were obtained from each biopsy specimen and deparaffinized with xylene, rehydrated in serially graded water–ethanol solution and rinsed in deionized water; they were then treated with proteinase K (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) (concentration 20 μg/ml in Tris–HCl pH 7.5) at room temperature for 5 min. The sections were immersed in pre-hybridization solution (50% formamide/4× SSC) to prevent background staining and then incubated with double FITC-human cytokine HybriProbe (Biognostik, Germany) overnight at 30°C. TNF-α probe was employed (20 units for 1,000 μl—HybriBuffer ISH). The detection and visualization procedure was made with anti-FITC/AP monoclonal antibody (Vector Laboratories, CA) and BCIP/NBT as substrate. The epidermis of discoid lupus scarring alopecia was used as positive control. Immunohistochemical specimens were graded semi-quantitatively under a light-field microscope at 100× magnification.

Results

Clinical and Histopathologic Findings

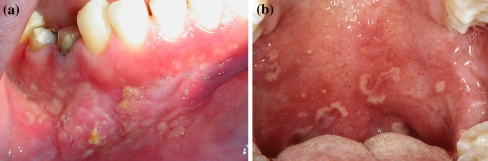

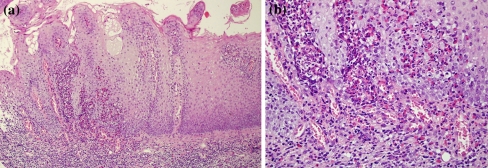

Patient’s clinical characteristics are given in Table 1. All patients were affected by long-standing multiple mucosal ulcerations and yellow pustules mainly located in the vestibular, gingival and palatal mucosa (Fig. 1a, b). Microscopic examination revealed in all specimens an ulcerated epithelium with characteristic intraepithelial and/or subepithelial micro abscesses containing abundant eosinophils plus a mixed infiltrate formed by lymphocytes, neutrophils and few plasma cells (Fig. 2a, b).

Fig. 1.

aPatient 1 Multiple mucosal ulcerations and yellow pustules are visible on the lower vestibular and gingival mucosa; bPatient 3 Ulcers and irregular yellow pustules on the soft palate

Fig. 2.

Patient 1a Hyperplastic epithelium with characteristic intraepithelial and/or subepithelial micro abscesses (H&E, original magnification ×10); b at higher magnification abundant eosinophils plus a mixed infiltrate mainly formed by mononuclear cells, neutrophils ad plasma cells are visible (H&E, original magnification ×40)

Immunohistochemical and In situ Hybridization Analysis

Cellular Immune Profile of the Inflammatory Infiltrate

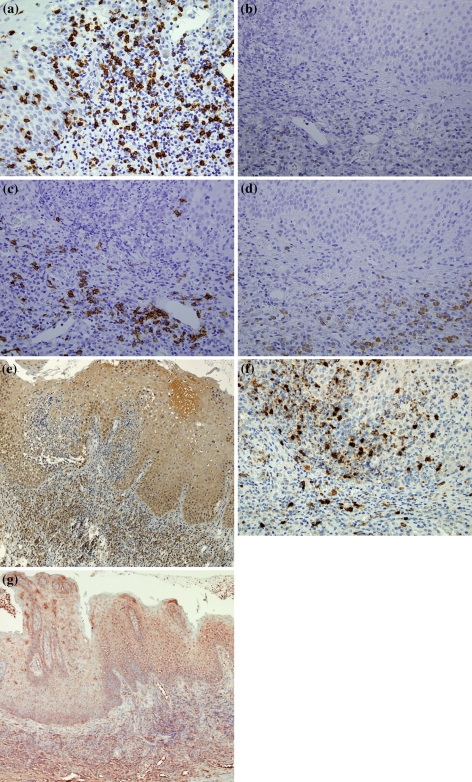

In cases of PV, the analysis of the cellular immune profile of the inflammatory infiltrate showed a predominance of T-lymphocytes, mainly of cytotoxic (CD3+/CD8+) phenotype, over B-cells. Cytotoxic (CD3+/CD8+) lymphocytes were also found in a scattered fashion within the epithelial lamina. CD20+ B-lymphocytes were also identified in lesser amount among the lymphoid cells present in the lamina propria, while they were virtually absent in the epithelial lamina. CD79a+ plasma cells were moderately present in the lamina propria infiltrate of two PV specimens. CD4+ lymphocytes were absent in all PV specimens (Fig. 3a–d). Detailed results of the IHC and ISH analysis for each specimen are given in Table 1.

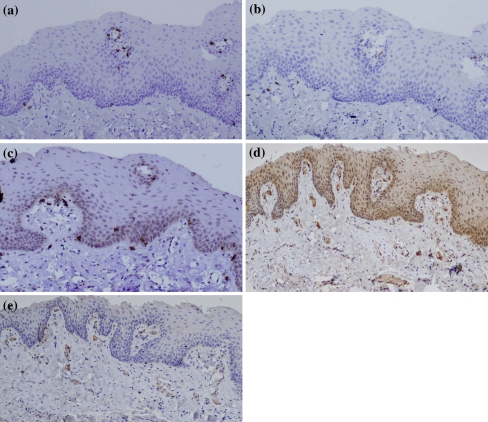

Fig. 3.

Patient 1a The inflammatory infiltrate shows a predominance of cytotoxic CD8+ T-lymphocytes (×40); b very few CD4+ T-lymphocytes are evident in the lamina propria (×40); c CD20+ B-lymphocytes (×40); d CD79a+ cells are well visible in the lamina propria (×40); e IL-6 positivity is present in the cytoplasm of inflammatory mononuclear cells and epithelial cells mainly of the lower third of the epithelial lamina (×10); f IL-8 expression is evident mainly in the cytoplasm of inflammatory mononuclear cells (×40); g By ISH analysis, TNF-α appears markedly expressed in the cytoplasm of both epithelial and inflammatory mononuclear cells (×10)

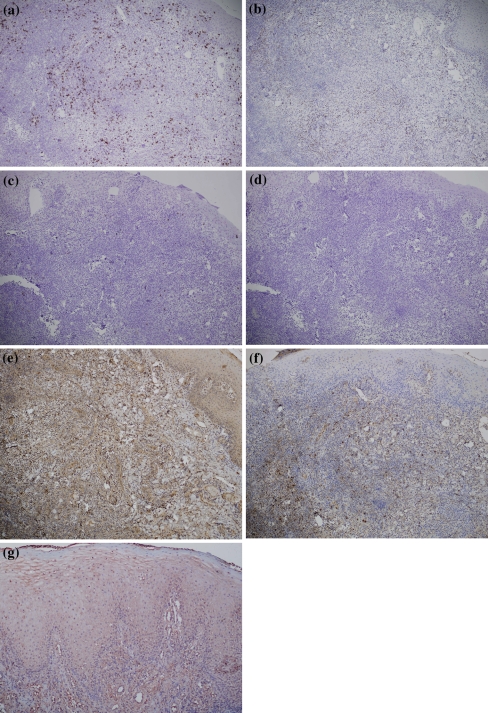

Analysis of control tissues has shown overlapping results with those seen in PV cases. A difference was the presence of CD4+ lymphocytes, in both the epithelial and lamina propria, in the LP and RAS tissue biopsies. The normal buccal mucosa showed, as expected, only positivity for few scattered cytotoxic CD8+ and CD4+ lymphocytes around capillaries. CD79a+ plasma cells were absent in all control specimens (Fig. 4a–d). Detailed results for each control specimen are given in Table 2.

Fig. 4.

Control tissue, Case 2a predominance of cytotoxic CD8+ T-lymphocytes in the inflammatory infiltrate (×10); b fewer CD4+ T-lymphocytes are present in the lamina propria (×10); c few scattered CD20+ B-lymphocytes are evident (×10); d CD79a+ cells are absent (×10); e IL-6 positivity is shown in the cytoplasm of inflammatory mononuclear cells and epithelial cells (×10); f IL-8 expression is evident among inflammatory mononuclear cells; g TNF-α appears expressed in both epithelial lamina and inflammatory infiltrate (×10)

Table 2.

Cellular immune profile and IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α expression in control tissues

| Patient | Patients’ characteristics (Age/sex/disease) | CD3 | CD4 | CD8 | CD20 | CD79a | IL-6 | IL-8 | TNF-α | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC | EC | IC | EC | IC | EC | IC | EC | IC | EC | IC | EC | IC | EC | IC | EC | ||

| 1 | 20/M/EM | ++ | +a | − | − | + | +a | − | − | − | − | ++ | + | − | − | ++ | + |

| 2 | 30/F/RAS | +++ | ++a | ++ | + | +++ | +a | + | − | − | − | ++ | + | ++ | − | ++ | + |

| 3 | 40/F/LP | +++ | +a | +++ | + | +++ | ++a | +++ | − | + | − | +++ | + | ++ | − | +++ | + |

| 4 | 30/F/NBM | +b | +a | +b | − | +b | − | − | − | − | − | +c | − | +c | − | − | − |

Score system: as in Table 1

M male, F Female, EM erythema multiforme, RAS recurrent aphthous stomatitis, LP lichen planus, NBM normal buccal mucosa, IC inflammatory cells, EC epithelial cell

aPositivity limited to intraepithelial inflammatory cells; b Few positive cells at the basal membrane level; c scattered positive cells around capillaries

IL-6

In each PV tissue sample, IHC analysis detected expression of IL-6 in the cytoplasm of inflammatory mononuclear cells and epithelial cells mainly in the lower third of the epithelial lamina (Fig. 3e). IL-6 positivity appeared stronger among mononuclear cells of the inflammatory infiltrate. In all control tissues, IL-6 expression was mainly present in the mononuclear cells of the inflammatory infiltrate and less conspicuous in the epithelial cells (Fig. 4e). The normal buccal mucosa appeared negative with the exception of very few positive cells around capillaries (Fig. 5d) (see also Tables 1, 2).

Fig. 5.

Control tissue, normal buccal mucosaa rare cytotoxic CD8+ T-lymphocytes around capillaries and at the basal membrane level (×10); b rare CD4+ T-lymphocytes at the basal membrane level (×10); c scattered CD20+ B-lymphocytes at the basal membrane level (×10); d IL-6 positivity around capillaries (×10); e IL-8 positivity around capillaries (×10)

IL-8

In all PV specimens, IL-8 expression was well evident mainly in the cytoplasm of mononuclear cells of the inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 3f). Only one case showed IL-8 positivity among scattered intraepithelial inflammatory cells. As the control tissues, IL-8 expression was negative in the EM specimen but evident in the inflammatory infiltrate of the RAS (Fig. 4f) and LP tissues. The normal buccal mucosa showed scattered positive cells at the basal membrane level (Fig. 5e).

TNF-α

Expression of TNF-α was found by ISH in the cytoplasm and nuclei of both epithelial cells and inflammatory mononuclear cells of PV specimens (Fig. 3g). As the control tissues, TNF-α expression was positive in all specimens of EM, RAS (Fig. 4g) and LP; instead, the normal buccal mucosa was negative.

Discussion

PV is an extraintestinal manifestation of IBD which appears to have an inflammatory basis similar to that observed in IBD. Autoimmunity and genetic factors are thought to play a central role in the pathogenesis of IBD and associated extra-intestinal manifestations. Genetic polymorphisms have a pivotal role in determining the susceptibility of developing Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis, but also determine the phenotype of the disease, including extraintestinal features. It appears that dysregulated immune response to colonic bacteria might trigger T-cell mediated responses (T-cells that are cross-reactive to auto antigens), cytokine production and, as a consequence, the development of colonic and possibly extra colonic injury [11]. T-cells play an important role in these conditions and our findings imply that these cells are trafficking to the oral mucosa under the influence of an antigenic stimulus. The heavy presence of CD8+ T lymphocytes, together with the presence of macrophages and neutrophils, appears to be responsible for the epithelial damage and ulceration which are common findings in PV. Activated CD8+ T lymphocytes (and possible keratinocytes) may release chemokines that attract additional lymphocytes and other immune cells into the developing PV lesion.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines play a pivotal role in the recruitment of other inflammatory cells such as neutrophils and eosinophils. At the tissue level we found that all PV samples showed overexpression of IL-6 which is a pro-inflammatory (and anti-inflammatory as well) cytokine that mainly regulates the differentiation of activated B-cells into plasma cells and, as consequence, immunoglobulin secretion. IL-6, which is dysregulated in several inflammatory human diseases, is produced by keratinocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts and by leukocytes infiltrating the skin or mucosal membranes [15]. We also observed overexpression of IL-8 in the cytoplasm of macrophages scattered among the inflammatory infiltrate; it is well known that this cytokine is a potent chemotactic polypeptide for neutrophils and may also be involved in angiogenesis [14, 17]. In the literature, there is evidence for a role of IL-8 in the pathogenesis of pyoderma gangrenosum, since overexpression of this chemotactic cytokine has been found immunohistochemically in dermal fibroblast from ulcers of patients affected by this disease [18, 19].

We provide evidence for abundant expression of TNF-α in both epithelial cells and the inflammatory infiltrate suggesting that this potent pro-inflammatory cytokine, which leads to recruitment of inflammatory cells to areas of inflammation, could synergistically contribute to the proinflammatory pathogenetic mechanism of PV. TNF-α is a pivotal mediator of skin and mucosal inflammation, and its expression is induced in the course of almost all inflammatory diseases. This cytokine is mainly produced by keratinocytes which are stimulated by irritants. Exposure to TNF-α causes Langerhans cells to migrate to draining lymph nodes, which allows for sensitization of naïve T cells [13, 16]. Evidence of overexpression of TNF-α in tissue biopsies of patients with pyoderma gangrenosum has been reported by Bister et al. [20].

However, our data in control tissues also show that overexpression of IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α can be seen in other oral diseases such as EM, RAS and LP. These findings evidently imply that these cytokines do not represent specific markers of PV but speak in favour of a more “generic” pathogenic role strictly linked to the initiation and maintenance of the mucosal inflammatory process.

Although our data partially explains some of the mechanisms implicated in the genesis of the local inflammatory response, they do not provide any clue on the initiation of the antigenic stimulation which triggers the development of PV lesions.

We speculate that anti-IL6, anti-IL-8 and anti-TNF-α drugs may have a therapeutic role in PV; there are, however, only anecdotal studies that have reported on the efficacy of drugs such as infliximab or other immunomodulator treatments [21–24]. It is important to stress the concept that IBD are often systemic diseases with an extraintestinal counterpart which points toward a pathogenesis linked to immunogenetic mechanisms. Indeed, in patients with PV, resolution of extraintestinal manifestations have been observed with treatment of bowel disease [2, 5, 7].

Conclusions

Mucosal inflammation in PV shares some pathogenic similarities with IBD. In particular, the inflammatory infiltrate shows a predominance of cytotoxic (CD3+/CD8+) lymphocytes. We provide evidence for a simultaneous overexpression of IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α, suggesting that these factors, although not specific to PV, could synergistically contribute to the proinflammatory mechanism of this rare oral condition. In addition, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8 being important regulatory factors of inflammation would represent a suitable therapeutic target. In recent years a vast expansion in the understanding of cytokines/chemokines biology has occurred. These substances and their receptors are now known to play a crucial part in directing the movement of mononuclear cells throughout the body, engendering the adaptive immune response and contributing to the pathogenesis of a variety of diseases. However, the complexity of the cytokines/chemokines network and their numerous functions require further studies in order to confirm our findings.

References

- 1.Hansen LS, Silverman S, Jr, Daniels TE. The differential diagnosis of pyostomatitis vegetans and its relation to bowel disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55:363–373. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(83)90191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ficarra G, Cicchi P, Amorosi A, Piluso S. Oral Crohn’s disease and pyostomatitis vegetans. An unusual association. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;75:220–224. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90097-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Storwick GS, Prihoda MB, Fulton RJ, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans: a specific marker for inflammatory bowel disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:336–341. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nigen S, Poulin Y, Rochette L, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans: two cases and a review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:250–255. doi: 10.1007/s10227-002-0112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hegarty AW, Barrett AM, Scully C. Pyostomatitis vegetans. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leibovitch I, Ooi C, Huilgol SC, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans of the eyelids. Case report and review of the literature. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1809–1813. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kethu SR. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:467–475. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200607000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markieewicz M, Sursh L, Margarone J, et al. Pyostomatitis vegetans: a clinical marker of silent ulcerative colitis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:346–348. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callen JP, Jackson JM. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an update. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2007;33:787–802. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powell FC, Hackett BC, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al., editors. Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine. 7. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008. pp. 296–302. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sartor RB. Mechanisms of diseases: pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Nature Clin Practice. 2006;3:390–407. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooklyn TN, Williams AM, Dunnill MGS, et al. T-cell receptor in pyoderma gangrenosum: evidence for clonal expansion and trafficking. Clin Lab Invest 2007. doi 10.1111/i.1365.2133.2007.08211x . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Dinarello CA. Historical insights into cytokines. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:S34–S45. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi Y. The role of chemokines in neutrophils biology. Frontiers Biosci. 2008;13:2400–2407. doi: 10.2741/2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modlin RL, Kim J, Maurer D, et al. Innate and adaptive immunity in the skin. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al., editors. Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine. 7. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008. pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tayal V, Kalra BS. Cytokines and anti-cytokines as therapeutics-an update. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;579:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charo IF, Ranshoff RM. The many roles of chemokines and chemokines receptors in inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:610–621. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oka M, Berking C, Nesbit M, et al. Interleukin-8 overexpression is present in pyoderma gangrenosum ulcers and leads to ulcer formation in human skin xenografts. Lab Invest. 2000;80:595–604. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oka M. Pyoderma gangrenosum and interleukin 8. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:279–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bister V, Makitalo L, Jeskanen L, et al. Expression of MMP-9, MMP-10 and TNF-α and lack of epithelial MMP-1 and MMP-26 characterize pyoderma gangrenosum. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:889–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bens G, Laharie D, Beylot-Barry M, et al. Successful treatment with infliximab and methotrexate of PV associated with Crohn’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:181–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brinkmeier T, Frosch PG. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans: a clinical course of two decades with response to cyclosporine and low-dose prednisolone. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:134–136. doi: 10.1080/00015550152384290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogge FJ, Pacifico M, Kang N. Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum with the anti-TNF-alpha drug-Etanercept. J Plastic Reconstr Aest Surg. 2008;61:431–433. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werchniak AE, Storm CA, Punkett RW, et al. Treatment of pyostomatitis vegetans with topical tacrolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:722–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]