Abstract

An altered acid–base balance following ascent to high altitude has been well established. Such changes in pH buffering could potentially account for the observed increase in ventilatory CO2 sensitivity at high altitude. Likewise, if [H+] is the main determinant of cerebrovascular tone, then an alteration in pH buffering may also enhance the cerebral blood flow (CBF) responsiveness to CO2 (termed cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity). However, the effect altered acid–base balance associated with high altitude ascent on cerebrovascular and ventilatory responsiveness to CO2 remains unclear. We measured ventilation  , middle cerebral artery velocity (MCAv; index of CBF) and arterial blood gases at sea level and following ascent to 5050 m in 17 healthy participants during modified hyperoxic rebreathing. At 5050 m, resting

, middle cerebral artery velocity (MCAv; index of CBF) and arterial blood gases at sea level and following ascent to 5050 m in 17 healthy participants during modified hyperoxic rebreathing. At 5050 m, resting  , MCAv and pH were higher (P < 0.01), while bicarbonate concentration and partial pressures of arterial O2 and CO2 were lower (P < 0.01) compared to sea level. Ascent to 5050 m also increased the hypercapnic MCAv CO2 reactivity (2.9 ± 1.1 vs. 4.8 ± 1.4% mmHg−1; P < 0.01) and

, MCAv and pH were higher (P < 0.01), while bicarbonate concentration and partial pressures of arterial O2 and CO2 were lower (P < 0.01) compared to sea level. Ascent to 5050 m also increased the hypercapnic MCAv CO2 reactivity (2.9 ± 1.1 vs. 4.8 ± 1.4% mmHg−1; P < 0.01) and  CO2 sensitivity (3.6 ± 2.3 vs. 5.1 ± 1.7 l min−1 mmHg−1; P < 0.01). Likewise, the hypocapnic MCAv CO2 reactivity was increased at 5050 m (4.2 ± 1.0 vs. 2.0 ± 0.6% mmHg−1; P < 0.01). The hypercapnic MCAv CO2 reactivity correlated with resting pH at high altitude (R2= 0.4; P < 0.01) while the central chemoreflex threshold correlated with bicarbonate concentration (R2= 0.7; P < 0.01). These findings indicate that (1) ascent to high altitude increases the ventilatory CO2 sensitivity and elevates the cerebrovascular responsiveness to hypercapnia and hypocapnia, and (2) alterations in cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and central chemoreflex may be partly attributed to an acid–base balance associated with high altitude ascent. Collectively, our findings provide new insights into the influence of high altitude on cerebrovascular function and highlight the potential role of alterations in acid–base balance in the regulation in CBF and ventilatory control.

CO2 sensitivity (3.6 ± 2.3 vs. 5.1 ± 1.7 l min−1 mmHg−1; P < 0.01). Likewise, the hypocapnic MCAv CO2 reactivity was increased at 5050 m (4.2 ± 1.0 vs. 2.0 ± 0.6% mmHg−1; P < 0.01). The hypercapnic MCAv CO2 reactivity correlated with resting pH at high altitude (R2= 0.4; P < 0.01) while the central chemoreflex threshold correlated with bicarbonate concentration (R2= 0.7; P < 0.01). These findings indicate that (1) ascent to high altitude increases the ventilatory CO2 sensitivity and elevates the cerebrovascular responsiveness to hypercapnia and hypocapnia, and (2) alterations in cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and central chemoreflex may be partly attributed to an acid–base balance associated with high altitude ascent. Collectively, our findings provide new insights into the influence of high altitude on cerebrovascular function and highlight the potential role of alterations in acid–base balance in the regulation in CBF and ventilatory control.

Introduction

The cerebral blood flow (CBF) response to CO2 (termed cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity) is an important determinant of brain [H+], and therefore central chemoreceptor activation (Chapman et al. 1979; Xie et al. 2006; Ainslie & Duffin, 2009). Accordingly, tight control of the cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity provides an important regulatory mechanism to minimise changes in brain [H+], and thereby stabilise breathing in the face of perturbations in partial pressure of arterial CO2 . Indeed, previous studies have reported a link between blunted cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and the occurrence of central sleep apnoea in patients with congestive heart failure (Xie et al. 2005) and also in the pathophysiology of obstructive sleep apnoea (Burgess et al. 2010; Reichmuth et al. 2010). Accordingly, a reduction in CBF responsiveness to CO2 may account, at least in part, for the development of periodic breathing commonly observed in newcomers to high altitude (Ainslie et al. 2007; Ainslie & Duffin, 2009). However, the effect of high altitude exposure on cerebrovascular function remains unclear. For example, studies have reported either reduced (Ainslie & Burgess, 2008) or unchanged (Jansen et al. 1999) CBF responsiveness to hypercapnia in newcomers to high altitude. In contrast, short duration (e.g. 60 min; Blaber et al. 2003) and moderate duration (e.g. >4 days; Jansen et al. 1999) exposure to high altitude enhanced hypocapnic cerebrovascular reactivity. Differences in experimental protocol (exposure duration), method of assessing CBF reactivity (steady-state vs. rebreathing; Ainslie & Duffin, 2009), degree and type of hypoxic exposure (simulated vs. high altitude), and limited sample size may explain the differences in the observed CBF reactivity following exposure to high altitude. These inconsistent results are difficult to reconcile, and thus further study is warranted to clarify the effect of high altitude on cerebrovascular reactivity.

. Indeed, previous studies have reported a link between blunted cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and the occurrence of central sleep apnoea in patients with congestive heart failure (Xie et al. 2005) and also in the pathophysiology of obstructive sleep apnoea (Burgess et al. 2010; Reichmuth et al. 2010). Accordingly, a reduction in CBF responsiveness to CO2 may account, at least in part, for the development of periodic breathing commonly observed in newcomers to high altitude (Ainslie et al. 2007; Ainslie & Duffin, 2009). However, the effect of high altitude exposure on cerebrovascular function remains unclear. For example, studies have reported either reduced (Ainslie & Burgess, 2008) or unchanged (Jansen et al. 1999) CBF responsiveness to hypercapnia in newcomers to high altitude. In contrast, short duration (e.g. 60 min; Blaber et al. 2003) and moderate duration (e.g. >4 days; Jansen et al. 1999) exposure to high altitude enhanced hypocapnic cerebrovascular reactivity. Differences in experimental protocol (exposure duration), method of assessing CBF reactivity (steady-state vs. rebreathing; Ainslie & Duffin, 2009), degree and type of hypoxic exposure (simulated vs. high altitude), and limited sample size may explain the differences in the observed CBF reactivity following exposure to high altitude. These inconsistent results are difficult to reconcile, and thus further study is warranted to clarify the effect of high altitude on cerebrovascular reactivity.

Alteration in acid–base balance during high altitude exposure has been well documented (Dempsey et al. 1974; Forster et al. 1975; Weiskopf et al. 1976). Importantly, such changes in pH buffering could potentially account for the increase in ventilatory CO2 sensitivity following ascent to high altitude (Mathew et al. 1983; Schoene et al. 1990). For example, if an altered pH buffering leads to a greater rise in arterial [H+] and presumably central [H+], for a given rise in  , then an individual at high altitude would have a higher ventilatory responsiveness to CO2 compared to sea level. Likewise, if cerebrovascular tone is determined by arterial [H+], rather than

, then an individual at high altitude would have a higher ventilatory responsiveness to CO2 compared to sea level. Likewise, if cerebrovascular tone is determined by arterial [H+], rather than  per se, then ascent to high altitude would also enhance the CBF responsiveness to changes in

per se, then ascent to high altitude would also enhance the CBF responsiveness to changes in  . Therefore, alterations in pH buffering may partly explain the well-reported elevations in central chemoreflex activity and potentially result in elevations in cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity. However, the influence of altered acid–base balance associated with high altitude exposure on the CBF responsiveness to CO2 has not been examined.

. Therefore, alterations in pH buffering may partly explain the well-reported elevations in central chemoreflex activity and potentially result in elevations in cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity. However, the influence of altered acid–base balance associated with high altitude exposure on the CBF responsiveness to CO2 has not been examined.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of high altitude ascent on the cerebrovascular reactivity and ventilatory responsiveness to CO2. We test the hypothesis that an altered acid–base balance associated with ascent to high altitude would enhance the cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and potentially account, at least in part, for the increase in ventilatory CO2 sensitivity in newcomers to high altitude.

Methods

Seventeen people participated in the study: eleven male and six female, aged 31 ± 9 years (mean ±s.d.), with body mass index of 23 ± 2 kg m−2. They were non-smokers, had no previous history of cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, or respiratory diseases and were not taking any cardiovascular medications. All participants were informed of the purposes and procedures of the study, and informed consent was given prior to participation. The study was approved by the Lower South Regional Ethics Committee of Otago and conformed to the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Experimental design

The participants were required to visit the laboratory on three occasions. After a full familiarisation with the experimental procedures outlined below (visit 1), the participants underwent two experimental trials, one at sea level (Dunedin, New Zealand; barometric pressure ∼755 ± 7 mmHg) and one at high altitude (5050 m; the Ev-K2-CNR Pyramid Laboratory, Khumbu Valley, Nepal, at the base of Mt Everest; barometric pressure ∼412 ± 1 mmHg). The trip from New Zealand to the Pyramid Laboratory, was done in two stages. First, the group flew to Kathmandu (1340 m), where they stayed for 7 days. They then flew to Lukla, located at 2860 m, and trekked to the Pyramid Laboratory over 8 days including two compulsory acclimatisation days, at 3450 m (day 4) and at 4252 m (day 7). Importantly, to avoid the confounding influence of altitude illness, experimental sessions were carried out between days 2 and 4 after arrival at 5050 m.

Experimental session

Before each experimental session, the participants were instructed to abstain from exercise and alcohol for 24 h and caffeine for 12 h, and they did not consume a heavy meal within 4 h of testing. Where possible, the participants were tested at the same time of day at sea level and 5050 m.

With the exception of arterial blood gas sampling, which was conducted following 10 min supine rest, all experiments were performed with participants semi-recumbent. In brief, each experimental testing session comprised procurement of an arterial blood gas sample, equipment instrumentation and a 5 min baseline data collection period. Following the 5 min baseline, participants underwent a modified rebreathing ventilatory response test.

Modified rebreathing

The participants wore a nose clip and breathed through a mouthpiece connected to a Y-valve which allowed switching from room air to a 6 l rebreathing bag filled with 7% CO2 and 93% O2. The modified rebreathing test began with a 2 min baseline room air breathing followed by 5 min voluntary hyperventilation. For this, participants were instructed and given verbal feedback to increase ventilation  (via depth and frequency) to lower and then maintain partial pressure of end-tidal CO2

(via depth and frequency) to lower and then maintain partial pressure of end-tidal CO2 at 22 ± 2 mmHg (sea level) and 17 ± 3 mmHg (5050 m). Participants were then switched to the rebreathing bag following an expiration. They were then instructed to take three deep breaths to ensure rapid equalisation of

at 22 ± 2 mmHg (sea level) and 17 ± 3 mmHg (5050 m). Participants were then switched to the rebreathing bag following an expiration. They were then instructed to take three deep breaths to ensure rapid equalisation of  between the rebreathing bag and the alveolar, arterial and mixed-venous compartments. The modified rebreathing tests were terminated when one of the following applied: (i)

between the rebreathing bag and the alveolar, arterial and mixed-venous compartments. The modified rebreathing tests were terminated when one of the following applied: (i)  reached 60 mmHg; (ii) partial pressure of end-tidal O2

reached 60 mmHg; (ii) partial pressure of end-tidal O2 could no longer be maintained above 160 mmHg; (iii)

could no longer be maintained above 160 mmHg; (iii)  exceeded 100 l min−1; or (iv) the participant reached the end of their tolerance. Further details about this test have been described elsewhere (Mohan & Duffin, 1997; Mohan et al. 1999; Duffin et al. 2000). In the current study,

exceeded 100 l min−1; or (iv) the participant reached the end of their tolerance. Further details about this test have been described elsewhere (Mohan & Duffin, 1997; Mohan et al. 1999; Duffin et al. 2000). In the current study,  progressively fell through the hyperoxic ranges during the modified rebreathing and the test was terminated when

progressively fell through the hyperoxic ranges during the modified rebreathing and the test was terminated when  was reduced <160 mmHg. Previous studies have established that hyperoxia (

was reduced <160 mmHg. Previous studies have established that hyperoxia ( ≥ 150 mmHg) silences the peripheral chemoreceptors (Cunningham et al. 1963; Gardner, 1980; Mohan & Duffin, 1997).

≥ 150 mmHg) silences the peripheral chemoreceptors (Cunningham et al. 1963; Gardner, 1980; Mohan & Duffin, 1997).

Measurements

Respiratory variables

and its components of tidal volume (VT) and breathing frequency (f) were measured using a heated pneumotachograph (Hans-Rudolph HR800) and expressed in units adjusted to Body Temperature Pressure Saturated (BTPS). The fractional changes in inspired and expired O2 and CO2 were used to calculate

and its components of tidal volume (VT) and breathing frequency (f) were measured using a heated pneumotachograph (Hans-Rudolph HR800) and expressed in units adjusted to Body Temperature Pressure Saturated (BTPS). The fractional changes in inspired and expired O2 and CO2 were used to calculate  and

and  using fast responding gas analysers (model CD-3A, AEI Technologies, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; ML206 and ML240, ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). The pneumotachograph was calibrated using a 3 l syringe (Hans-Rudolph 2700, Kansas City, MO, USA) and the gas analysers were calibrated using known concentrations of O2 and CO2 prior to each testing session.

using fast responding gas analysers (model CD-3A, AEI Technologies, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; ML206 and ML240, ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). The pneumotachograph was calibrated using a 3 l syringe (Hans-Rudolph 2700, Kansas City, MO, USA) and the gas analysers were calibrated using known concentrations of O2 and CO2 prior to each testing session.

Cerebrovascular and cardiovascular variables

Middle cerebral artery velocity (MCAv, an index of cerebral blood flow) was measured in the right middle cerebral artery using a 2 MHz pulsed Doppler ultrasound system (DWL Doppler, Sterling, VA, USA). The Doppler ultrasound probe was positioned over the right temporal window and held in place with an adjustable plastic headband. The signals were obtained using search techniques described elsewhere (Aaslid et al. 1982). Heart rate (HR) was determined using a three-lead ECG while beat-to-beat mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) was monitored using finger photoplethysmography (Finometer, TPD Biomedical Instrumentation, Paasheuvelweg, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Manual blood pressure measurements by auscultation were also made periodically to check and validate the automated recordings. Cerebrovascular conductance index (CVCi) was subsequently estimated by dividing mean MCAv by MAP within each breath cycle to reveal intrinsic vascular responses to CO2 (Claassen et al. 2007).

Arterial blood gas variables

Arterial blood variables (pH, partial pressure of arterial O2 , partial pressure of arterial CO2

, partial pressure of arterial CO2 , arterial O2 saturation

, arterial O2 saturation  , bicarbonate concentration [HCO3−], standard basic excess (SBE), haematocrit (Hct) and total haemoglobin concentration (ctHb)) from the radial artery were obtained after 10 min supine rest using a 25-gauge needle into a preheparinised syringe. Following standardised calibration, all blood samples were analysed using an arterial blood-gas analysing system (NPT7 series, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark).

, bicarbonate concentration [HCO3−], standard basic excess (SBE), haematocrit (Hct) and total haemoglobin concentration (ctHb)) from the radial artery were obtained after 10 min supine rest using a 25-gauge needle into a preheparinised syringe. Following standardised calibration, all blood samples were analysed using an arterial blood-gas analysing system (NPT7 series, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark).

With the exception of the arterial blood gases, all data were acquired at 200 Hz using an analog to digital converter (PowerLab, ADInstruments) with commercially available software (Chart v. 5.5.6, ADInstruments), and stored on computer for later analysis.

Data analysis

The modified rebreathing data were accumulated on a breath-by-breath basis and analysed using a specially designed program (Full Fit Rebreathing program, v. 3.1, Toronto, Canada). Breaths from the initial three-breath equilibration, as well as sighs, swallows and breaths incorrectly detected by the acquisition software were excluded from further analysis. Next, the breath-by-breath  values were plotted against time and fitted with a least squares regression line to minimise inter-breath variability (Mohan et al. 1999; Duffin et al. 2000). Subsequently,

values were plotted against time and fitted with a least squares regression line to minimise inter-breath variability (Mohan et al. 1999; Duffin et al. 2000). Subsequently,  , MCAv, CVCi, MAP and HR were plotted against the predicted

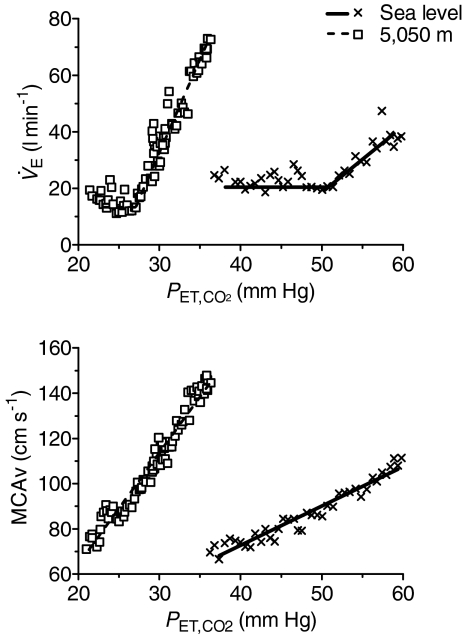

, MCAv, CVCi, MAP and HR were plotted against the predicted  (Fig. 1).

(Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Ventilation ( ) and middle cerebral artery velocity (MCAv) vs. end-tidal

) and middle cerebral artery velocity (MCAv) vs. end-tidal (

( ) from a representative individual during the modified rebreathing method at sea level and following ascent to 5050 m This graph depicts the typical breath-by-breath

) from a representative individual during the modified rebreathing method at sea level and following ascent to 5050 m This graph depicts the typical breath-by-breath  and MCAv vs.

and MCAv vs.  during modified rebreathing. The horizontal lines during modified rebreathing were used to calculate basal

during modified rebreathing. The horizontal lines during modified rebreathing were used to calculate basal  . The slopes represent linear regression used to calculate the ventilatory CO2 sensitivity and cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity during modified rebreathing.

. The slopes represent linear regression used to calculate the ventilatory CO2 sensitivity and cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity during modified rebreathing.

Ventilatory CO2 sensitivity

A full description of the analysis of the ventilatory slope during the modified rebreathing is described elsewhere (Mohan et al. 1999; Duffin et al. 2000). In brief, the  CO2 slope comprises two segments separated by one breakpoint. The first segment was fitted with a straight line and taken as a measure of the basal

CO2 slope comprises two segments separated by one breakpoint. The first segment was fitted with a straight line and taken as a measure of the basal  . Thereafter,

. Thereafter,  increased in conjunction with the predicted

increased in conjunction with the predicted  .

.

Cerebrovascular and cardiovascular CO2 reactivity

Linear regression was also applied to the MCAv, CVCi, MAP and HR changes during the modified rebreathing. Unlike the  response, there were no differential breakpoints observed in the MCAv, CVCi, MAP and HR response to CO2 in the majority (12 out of 17) of the participants; thus, in most cases, a single line was fitted (see methodological consideration; Fig. 1). Two regression lines were fitted in those participants (5 out of 17) with a distinct breakpoint in the MCAv response to CO2, and only the first slope was used for further analysis to enable comparison with the

response, there were no differential breakpoints observed in the MCAv, CVCi, MAP and HR response to CO2 in the majority (12 out of 17) of the participants; thus, in most cases, a single line was fitted (see methodological consideration; Fig. 1). Two regression lines were fitted in those participants (5 out of 17) with a distinct breakpoint in the MCAv response to CO2, and only the first slope was used for further analysis to enable comparison with the  response. In all of the above analysis, modelling was based on the sum of least squares for non-linear regression using LabVIEW software (Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm, LabVIEW 7.1, National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA).

response. In all of the above analysis, modelling was based on the sum of least squares for non-linear regression using LabVIEW software (Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm, LabVIEW 7.1, National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA).

Steady-state hypocapnic cerebrovascular reactivity

Steady-state hypocapnic cerebrovascular reactivity was estimated from the slope of the mean MCAv in the final minute of baseline and voluntary hyperventilation prior to the rebreathing.

Statistical analysis

The changes in resting arterial blood variables, respiratory, cerebrovascular and cardiovascular variables following ascent to 5050 m were assessed with Student's t test for paired data (SPSS v. 17.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Likewise, the changes in ventilatory, cerebrovascular and cardiovascular CO2 sensitivities following ascent to 5050 m were assessed with paired t tests. The interactions between these dependant variables of interest were assessed using Pearson's correlational analysis. Statistical significance for all two-tailed tests was established at an α-level of 0.05, and data are expressed as means ±s.d.

Results

All 17 participants were able to complete the entire experimental protocol at sea level and following ascent to 5050 m.

Baseline

At 5050 m, resting  was elevated by 2.8 ± 3.9 l min−1 (vs. sea level, P < 0.01; Table 1), mediated by a 3 ± 5 breath min−1 increase in f (P < 0.05; Table 1), while VT remained unchanged (P > 0.05).

was elevated by 2.8 ± 3.9 l min−1 (vs. sea level, P < 0.01; Table 1), mediated by a 3 ± 5 breath min−1 increase in f (P < 0.05; Table 1), while VT remained unchanged (P > 0.05).  and

and  were lowered by 61 ± 11 mmHg and 16 ± 4 mmHg, respectively, following ascent to 5050 m (vs. sea level, P < 0.01; Table 1). Ascent to 5050 m increased resting MCAv and HR by 31 ± 31% and 11 ± 13 beats min−1, respectively (vs. sea level, P < 0.01; Table 1), while no significant changes were observed with either MAP or CVCi (P > 0.05). High altitude ascent lowered

were lowered by 61 ± 11 mmHg and 16 ± 4 mmHg, respectively, following ascent to 5050 m (vs. sea level, P < 0.01; Table 1). Ascent to 5050 m increased resting MCAv and HR by 31 ± 31% and 11 ± 13 beats min−1, respectively (vs. sea level, P < 0.01; Table 1), while no significant changes were observed with either MAP or CVCi (P > 0.05). High altitude ascent lowered  by 61 ± 12 mmHg (P < 0.01; Table 1) and

by 61 ± 12 mmHg (P < 0.01; Table 1) and  by 12 ± 3 mmHg (P < 0.01) compared to sea level values. At 5050 m,

by 12 ± 3 mmHg (P < 0.01) compared to sea level values. At 5050 m,  , [HCO3−] and SBE were reduced by 18.5 ± 3.5%, 7.3 ± 3.1 mmol l−1 and 6.5 ± 3.2 units, respectively (P < 0.01; Table 1) compared to sea level, while pH and Hct were increased by 0.02 ± 0.03 units (P < 0.01) and 1.7 ± 2.4%, respectively (vs. sea level, P < 0.05).

, [HCO3−] and SBE were reduced by 18.5 ± 3.5%, 7.3 ± 3.1 mmol l−1 and 6.5 ± 3.2 units, respectively (P < 0.01; Table 1) compared to sea level, while pH and Hct were increased by 0.02 ± 0.03 units (P < 0.01) and 1.7 ± 2.4%, respectively (vs. sea level, P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline respiratory and cerebrovascular variables at sea level and following ascent to 5050 m

| Sea level | 5050 m | |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | ||

(l min−1) (l min−1) |

13.5 ± 1.8 | 16.3 ± 4.2** |

| f (breath min−1) | 15 ± 4 | 17 ± 4* |

| VT (l) | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

41 ± 3.4 | 26 ± 3** |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

108 ± 8 | 47 ± 6** |

| Cardiovascular | ||

| HR (b min−1) | 70 ± 11 | 80 ± 10** |

| MAP (mmHg) | 81 ± 14 | 90 ± 15 |

| Cerebrovascular | ||

| MCAv (cm s−1) | 66 ± 11 | 85 ± 17** |

| CVCi (cm s−1 mmHg−1) | 0.85 ± 0.24 | 0.96 ± 0.20 |

| Arterial blood gases | ||

| pH | 7.45 ± 0.04 | 7.47 ± 0.03* |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

42 ± 3 | 29 ± 3** |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

105 ± 11 | 44 ± 3** |

(%) (%) |

98.4 ± 0.05 | 79.9 ± 3.4** |

| [HCO3−] (mmol l−1) | 28.6 ± 3.1 | 21.3 ± 2.4** |

| SBE | 4.6 ± 3.1 | −1.9 ± 2.5** |

| Hct (%) | 45.0 ± 3.9 | 45.7 ± 3.9* |

| ctHb (g l−1) | 14.6 ± 1.2 | 14.9 ± 1.3 |

Values are expressed as means ±s.d. Different from sea level:

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01.

Modified rebreathing

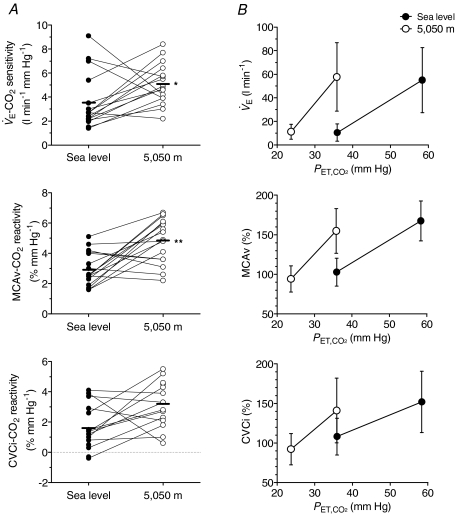

At 5050 m, the duration of the rebreathing test was shortened (vs. sea level, P < 0.05; Table 2) while the rate of CO2 rise was higher (P < 0.01) when compared to sea level. Ascent to 5050 m increased the  CO2 sensitivity by 1.5 ± 2.7 l min−1 mmHg−1 (3.6 ± 2.3 vs. 5.1 ± 1.7 l min−1 mmHg−1; P < 0.01; Fig. 2) compared to sea-level values. The ventilatory recruitment threshold was lowered by 16 ± 4 mmHg following ascent to high altitude (vs. sea level, P < 0.01; Table 2) while no change was observed in the basal

CO2 sensitivity by 1.5 ± 2.7 l min−1 mmHg−1 (3.6 ± 2.3 vs. 5.1 ± 1.7 l min−1 mmHg−1; P < 0.01; Fig. 2) compared to sea-level values. The ventilatory recruitment threshold was lowered by 16 ± 4 mmHg following ascent to high altitude (vs. sea level, P < 0.01; Table 2) while no change was observed in the basal  (P > 0.05; Table 2). Ascent to 5050 m elevated MCAv CO2 reactivity by 90 ± 92% (2.9 ± 1.1 vs. 4.8 ± 1.4% mmHg−1; P < 0.01; Fig. 2) while the CVCi CO2 reactivity remained unchanged (P > 0.05) when compared to sea-level values. Likewise, the HR CO2 sensitivity was elevated by 1.2 ± 1.4 beats min−1 mmHg−1 (0.3 ± 0.9 vs. 1.5 ± 1.4 beats min−1 mmHg−1; P < 0.01) following ascent to high altitude. No changes were observed in the MAP CO2 reactivity (1.0 ± 0.7 vs. 1.4 ± 0.8 mmHg mmHg−1; P > 0.05).

(P > 0.05; Table 2). Ascent to 5050 m elevated MCAv CO2 reactivity by 90 ± 92% (2.9 ± 1.1 vs. 4.8 ± 1.4% mmHg−1; P < 0.01; Fig. 2) while the CVCi CO2 reactivity remained unchanged (P > 0.05) when compared to sea-level values. Likewise, the HR CO2 sensitivity was elevated by 1.2 ± 1.4 beats min−1 mmHg−1 (0.3 ± 0.9 vs. 1.5 ± 1.4 beats min−1 mmHg−1; P < 0.01) following ascent to high altitude. No changes were observed in the MAP CO2 reactivity (1.0 ± 0.7 vs. 1.4 ± 0.8 mmHg mmHg−1; P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Modified rebreathing ventilatory test parameters

| Sea level | 5050 m | |

|---|---|---|

| Duration (s) | 338 ± 68 | 272 ± 53* |

| Rate of CO2 rise (mmHg min−1) | 4.2 ± 1.2 | 2.7 ± 0.4** |

| Ventilatory recruitment threshold (mmHg) | 44 ± 4 | 28 ± 2** |

(l min−1) (l min−1) |

10.5 ± 7.4 | 11.1 ± 6.3 |

Values are expressed as means ±s.d. Different from sea level:

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Alterations in ventilatory and cerebrovascular responsiveness to hypercapnia at sea level and following ascent to 5050 m A, individual slopes; B group data (means ±s.d.).  , ventilation; MCAv, middle cerebral artery velocity; CVCi, cerebrovascular vascular conductance index. **Different from sea level (P < 0.01).

, ventilation; MCAv, middle cerebral artery velocity; CVCi, cerebrovascular vascular conductance index. **Different from sea level (P < 0.01).

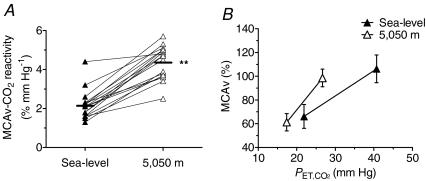

Voluntary hyperventilation lowered  and MCAv (P < 0.01; Table 3) and increased

and MCAv (P < 0.01; Table 3) and increased  by (P < 0.01) at both sea level and 5050 m. The MCAv response to hypocapnia was increased 115 ± 55% (2.0 ± 0.6 vs. 4.2 ± 1.0% mmHg−1; P < 0.01; Fig. 3) following ascent to high altitude.

by (P < 0.01) at both sea level and 5050 m. The MCAv response to hypocapnia was increased 115 ± 55% (2.0 ± 0.6 vs. 4.2 ± 1.0% mmHg−1; P < 0.01; Fig. 3) following ascent to high altitude.

Table 3.

Ventilatory, cerebrovascular and cardiovascular changes during steady-state hypocapnia

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

(l min−1) (l min−1) |

MCAv (cm s−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sea level | ||||

| Baseline | 41 ± 3 | 103 ± 9 | 13.4 ± 2.6 | 70 ± 11 |

| Hyperventilation | 22 ± 2** | 135 ± 4** | 35.6 ± 7.5** | 43 ± 8** |

| 5050 m | ||||

| Baseline | 26 ± 4** | 47 ± 6** | 17.9 ± 3.2 | 83 ± 14** |

| Hyperventilation | 17 ± 3‡ | 63 ± 6‡ | 39.1 ± 10.6‡ | 51 ± 7‡ |

Values are means ±s.d.

Different from sea level baseline (P < 0.01);

different from 5050 m baseline (P < 0.01).

Figure 3.

Alterations in hypocapnic cerebrovascular reactivity following ascent to 5050 m A, individual slopes; B, group data (mean ±s.d.). MCAv, middle cerebral artery velocity. Ascent to 5050 m enhanced the cerebrovascular responsiveness to hypocapnia (voluntary hyperventilatory). **Different from sea level (P < 0.01).

Relationships between selected variables

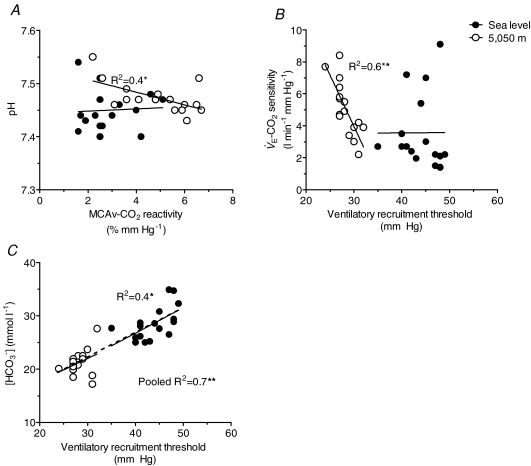

No significant relationships were observed between the  CO2 sensitivity and MCAv CO2 reactivity at sea level, following ascent to 5050 m, or from the pooled data (P > 0.05). Likewise, no significant correlations were observed between the changes in the

CO2 sensitivity and MCAv CO2 reactivity at sea level, following ascent to 5050 m, or from the pooled data (P > 0.05). Likewise, no significant correlations were observed between the changes in the  CO2 sensitivity and the changes in MCAv CO2 reactivity following ascent to 5050 m (P > 0.05). At 5050 m, MCAv CO2 reactivity correlated with resting pH (R2= 0.4; P < 0.01; Fig. 4A) while

CO2 sensitivity and the changes in MCAv CO2 reactivity following ascent to 5050 m (P > 0.05). At 5050 m, MCAv CO2 reactivity correlated with resting pH (R2= 0.4; P < 0.01; Fig. 4A) while  CO2 sensitivity correlated with the ventilatory recruitment threshold (R2= 0.6, P < 0.01; Fig. 4B). There were also significant correlations between resting [HCO3−] and the ventilatory recruitment threshold at both sea level (R2= 0.4; P < 0.05; Fig. 4C) and with data pooled from sea level and high altitude (R2= 0.7; P < 0.01).

CO2 sensitivity correlated with the ventilatory recruitment threshold (R2= 0.6, P < 0.01; Fig. 4B). There were also significant correlations between resting [HCO3−] and the ventilatory recruitment threshold at both sea level (R2= 0.4; P < 0.05; Fig. 4C) and with data pooled from sea level and high altitude (R2= 0.7; P < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Correlations between cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and ventilatory control with arterial blood gas variables Each point represents an individual subject at sea level and 5050 m. There were selective correlations between the cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity (MCAv CO2 reactivity) and pH at 5050 m, while no significant correlations were observed between MCAv CO2 reactivity with either bicarbonate concentration or partial pressure of arterial CO2. Ventilatory recruitment threshold correlated with [HCO3−] at sea level and pooled data and selectively correlated with ventilatory CO2 sensitivity ( CO2 sensitivity) at 5050 m. These findings indicate that the increase in MCAv CO2 reactivity and reduction in ventilatory recruitment threshold following ascent to 5050 m are related to an altered acid–balance balance. **Significant correlation (P < 0.01).

CO2 sensitivity) at 5050 m. These findings indicate that the increase in MCAv CO2 reactivity and reduction in ventilatory recruitment threshold following ascent to 5050 m are related to an altered acid–balance balance. **Significant correlation (P < 0.01).

Discussion

The major findings from the present study are that (1) ascent to high altitude enhances both ventilatory CO2 sensitivity and cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity; (2) hypercapnic cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity selectively correlates with pH at high altitude, and (3) there is a close link between the central chemoreflex threshold and bicarbonate concentrations. These findings indicate that alterations in pH buffering may partly account for the observed changes in ventilatory and cerebrovascular responsiveness to hypercapnia following ascent to high altitude.

Technological considerations

Assessment of CBF

In the present study, transcranial Doppler ultrasound was used to measure the middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity (MCAv) as an index of global CBF change following ascent to 5050 m and during alterations in  . The middle cerebral artery is commonly used as a index of global CBF because it carries approximately 80% of the blood volume to the respective hemisphere (Lindegaard et al. 1987). Whilst some previous studies (Roy et al. 1968; Milledge & Sorensen, 1972; Moller et al. 2002) have used direct measurement of global CBF, based on the Fick principle, the invasiveness of the arterial and internal jugular vein cannulation limits its use in repeat testing, and also for the assessment of cerebrovascular reactivity. Since transcranial Doppler ultrasound measures flow velocity and not CBF per se, the assessment of relative (normalised) changes in flow rather than absolute values is preferred. Nevertheless, research indicates that MCAv is a reliable and valid index of CBF (reviewed in Secher et al. 2008; Ainslie & Duffin, 2009) and mirrors the reported increases in CBF upon initial exposure to high altitude (4300–5260 m) as determined by the direct Fick method (e.g. Roy et al. 1968; Milledge & Sorensen, 1972; Moller et al. 2002). Moreover, since determinations of cerebrovascular reactivity are based on stimulus–response principles, direct CBF values are not as reliable or repeatable recordings with short (beat-to-beat) time resolution. For these reasons, transcranial Doppler ultrasound is a well-suited technique for field-based research.

. The middle cerebral artery is commonly used as a index of global CBF because it carries approximately 80% of the blood volume to the respective hemisphere (Lindegaard et al. 1987). Whilst some previous studies (Roy et al. 1968; Milledge & Sorensen, 1972; Moller et al. 2002) have used direct measurement of global CBF, based on the Fick principle, the invasiveness of the arterial and internal jugular vein cannulation limits its use in repeat testing, and also for the assessment of cerebrovascular reactivity. Since transcranial Doppler ultrasound measures flow velocity and not CBF per se, the assessment of relative (normalised) changes in flow rather than absolute values is preferred. Nevertheless, research indicates that MCAv is a reliable and valid index of CBF (reviewed in Secher et al. 2008; Ainslie & Duffin, 2009) and mirrors the reported increases in CBF upon initial exposure to high altitude (4300–5260 m) as determined by the direct Fick method (e.g. Roy et al. 1968; Milledge & Sorensen, 1972; Moller et al. 2002). Moreover, since determinations of cerebrovascular reactivity are based on stimulus–response principles, direct CBF values are not as reliable or repeatable recordings with short (beat-to-beat) time resolution. For these reasons, transcranial Doppler ultrasound is a well-suited technique for field-based research.

Modified rebreathing estimate of cerebrovascular CO2 responsiveness

In the present study, we observed a breakpoint in the MCAv response during the modified rebreathing method in 5 out of the 17 participants at sea level and in 4 out of 17 following ascent to 5050 m; in all these cases, this breakpoint was followed by either an increase or a decline in the MCAv CO2 slope. Interestingly, only two of these participants displayed such breakpoint at both sea level and following ascent to 5050 m. The cause of this MCAv breakpoint is unclear. Vovk et al. (2002) suggested that such breakpoints in the MCAv response during modified rebreathing could be due to the effect of the rising  overcoming the residual vasoconstrictory effect of prior hyperventilation-induced hypocapnia in the cerebral blood vessels. However, since the MCAv CO2 slope did not consistently increase following the breakpoint, it seems unlikely that the rise in

overcoming the residual vasoconstrictory effect of prior hyperventilation-induced hypocapnia in the cerebral blood vessels. However, since the MCAv CO2 slope did not consistently increase following the breakpoint, it seems unlikely that the rise in  during rebreathing could account for the observed breakpoint in the MCAv response.

during rebreathing could account for the observed breakpoint in the MCAv response.

Data variability

Variability of the baseline measurements was examined in a cohort (n= 12) of the same participants within another sea-level testing session undertaken at the same time of day. If the differences in CO2 responsiveness between sea level and high altitude were greater than the variability between the sea-level testing, this would support an altered physiological response following ascent to high altitude. At sea level, the between-day coefficient of variation was 61% for the  CO2 sensitivity and 31% for the MCAv CO2 reactivity. In addition, unpublished data from our laboratory revealed that the within-day coefficient of variance was 25% for the

CO2 sensitivity and 31% for the MCAv CO2 reactivity. In addition, unpublished data from our laboratory revealed that the within-day coefficient of variance was 25% for the  CO2 sensitivity and 37% for the MCAv CO2 reactivity. Therefore, the observed increases in both

CO2 sensitivity and 37% for the MCAv CO2 reactivity. Therefore, the observed increases in both  CO2 sensitivity (by 82%) and MCAv CO2 reactivity (by 90%) following ascent to 5050 m cannot be attributed to measurement variability.

CO2 sensitivity (by 82%) and MCAv CO2 reactivity (by 90%) following ascent to 5050 m cannot be attributed to measurement variability.

Enhanced ventilatory and cerebrovascular responsiveness to CO2 at high altitude

Previously, Mathew et al. (1983) reported an increase in the ventilatory responsiveness to hyperoxic rebreathing and a leftward shift in the x-intercept following exposure to 3500 m (1–3 weeks). Likewise, Schoene et al. (1990) found an increase in central chemoreflex during simulated ascent to 7315 m over a 40 day period. Meanwhile, central chemoreflex and threshold have been shown to remain unchanged following short duration isocapnic hypoxic exposure (20 min–3 h) (Mahamed & Duffin, 2001; Mahamed et al. 2003). In the present study, we observed a 1.3 l min−1 mmHg−1 increase in  CO2 sensitivity during hyperoxic modified rebreathing following ascent to 5050 m (Fig. 2). Moreover, we found a 15 mmHg reduction in the ventilatory recruitment threshold at 5050 m (Table 2). Since hyperoxia (

CO2 sensitivity during hyperoxic modified rebreathing following ascent to 5050 m (Fig. 2). Moreover, we found a 15 mmHg reduction in the ventilatory recruitment threshold at 5050 m (Table 2). Since hyperoxia ( mmHg) is known to silence the peripheral chemoreceptors (Cunningham et al. 1963; Gardner, 1980; Mohan & Duffin, 1997), we attribute these changes to an increase in the slope of the central chemoreflex and a reduction in the threshold for central chemoreflex activation at high altitude. In contrast to our findings, Somogyi et al. (2005) reported a leftward shift in the ventilatory recruitment threshold without any alterations in ventilatory CO2 sensitivity following 5 days at 3480 m. However, it should be noted that the findings from the Somogyi et al. (2005) study were based on data from five participants, whereas both Mathew et al. (1983) and the present study examined the effect of high altitude exposure on a much larger sample size (n= 20 and 17 respectively). Therefore, because of the known variability on the rebreathing response (Sahn et al. 1977; Mahamed & Duffin, 2001), the study of Somogyi et al. (2005) may have lacked sufficient statistical power to show the increase in ventilatory responsiveness to CO2 following ascent to high altitude.

mmHg) is known to silence the peripheral chemoreceptors (Cunningham et al. 1963; Gardner, 1980; Mohan & Duffin, 1997), we attribute these changes to an increase in the slope of the central chemoreflex and a reduction in the threshold for central chemoreflex activation at high altitude. In contrast to our findings, Somogyi et al. (2005) reported a leftward shift in the ventilatory recruitment threshold without any alterations in ventilatory CO2 sensitivity following 5 days at 3480 m. However, it should be noted that the findings from the Somogyi et al. (2005) study were based on data from five participants, whereas both Mathew et al. (1983) and the present study examined the effect of high altitude exposure on a much larger sample size (n= 20 and 17 respectively). Therefore, because of the known variability on the rebreathing response (Sahn et al. 1977; Mahamed & Duffin, 2001), the study of Somogyi et al. (2005) may have lacked sufficient statistical power to show the increase in ventilatory responsiveness to CO2 following ascent to high altitude.

In the present study, we observed a 90% increase in the modified rebreathing estimate of MCAv CO2 reactivity as well as a leftward shift in the slope MCAv response following ascent to 5050 m (Fig. 2). These findings are in contrast to some of our previous work (Ainslie & Burgess, 2008), where we observed a blunted MCAv response to modified rebreathing in five healthy participants at 3840 m. However, the participants examined in this previous study had spent ∼9 days at higher altitudes (>5000 m) prior to experimentation. Therefore, the effects of (relative) deacclimatisation could potentially explain the observed reduction in hypercapnic cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity. Importantly, the concomitant increases in both cerebrovascular and ventilatory responsiveness to CO2 observed in the present study during initial exposure to 5050 m suggest a common underpinning mechanism.

One potential mechanism which may account for the marked elevations in both  CO2 sensitivity and MCAv CO2 reactivity is an altered pH buffering associated with high altitude exposure (Dempsey et al. 1974; Forster et al. 1975; Weiskopf et al. 1976). In the present study, due to the incomplete compensatory metabolic acidosis counteracting the hypoxia-induced respiratory alkalosis (Severinghaus et al. 1963; Dempsey et al. 1974; Forster et al. 1975; Weiskopf et al. 1976), we observed an increase in arterial pH and a reduction in [HCO3−] following ascent to 5050 m (Table 1). Such alteration in acid–base balance could augment the

CO2 sensitivity and MCAv CO2 reactivity is an altered pH buffering associated with high altitude exposure (Dempsey et al. 1974; Forster et al. 1975; Weiskopf et al. 1976). In the present study, due to the incomplete compensatory metabolic acidosis counteracting the hypoxia-induced respiratory alkalosis (Severinghaus et al. 1963; Dempsey et al. 1974; Forster et al. 1975; Weiskopf et al. 1976), we observed an increase in arterial pH and a reduction in [HCO3−] following ascent to 5050 m (Table 1). Such alteration in acid–base balance could augment the  –H+ relationship, resulting in a greater rise in arterial and central [H+] for a given rise in

–H+ relationship, resulting in a greater rise in arterial and central [H+] for a given rise in  , thus enhancing the ventilatory CO2 sensitivity at high altitude. Furthermore, if the cerebral vessel walls respond to changes in arterial and/or arterial wall [H+] rather than

, thus enhancing the ventilatory CO2 sensitivity at high altitude. Furthermore, if the cerebral vessel walls respond to changes in arterial and/or arterial wall [H+] rather than  per se, then an altered pH buffering could also account for the observed increase in MCAv CO2 reactivity following ascent to 5050 m (Fig. 2). In support of these notions, the reduction in the central chemoreflex threshold associated with high altitude exposure was closely linked to the decrease in bicarbonate concentration (Fig. 4C). Meanwhile, we found the MCAv CO2 reactivity correlated negatively with arterial pH, but not with

per se, then an altered pH buffering could also account for the observed increase in MCAv CO2 reactivity following ascent to 5050 m (Fig. 2). In support of these notions, the reduction in the central chemoreflex threshold associated with high altitude exposure was closely linked to the decrease in bicarbonate concentration (Fig. 4C). Meanwhile, we found the MCAv CO2 reactivity correlated negatively with arterial pH, but not with  , at 5050 m (Fig. 4A). Although not establishing cause and effect, it would seem possible that cerebrovascular tone may be determined by arterial pH, rather than changes in

, at 5050 m (Fig. 4A). Although not establishing cause and effect, it would seem possible that cerebrovascular tone may be determined by arterial pH, rather than changes in  , at least at high altitude. Interestingly, Somogyi et al. (2005) provided evidence for an increase in the concentration of weakly dissociated protein anions such as albumin and phosphate following ascent to high altitude, while the strong ion difference remained unchanged. They proposed that this increase in weakly dissociated protein anions may account, in part, for the restoration of pH at high altitude. Whilst speculative, these findings support the idea that an altered pH buffering may account for the observed alterations in cerebrovascular and ventilatory responsiveness to CO2 following ascent to high altitude. The role of altered acid–base balance in cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and ventilatory control, either via renal compensation or altered weakly dissociated protein anion following ascent to high altitude, clearly warrants further investigation.

, at least at high altitude. Interestingly, Somogyi et al. (2005) provided evidence for an increase in the concentration of weakly dissociated protein anions such as albumin and phosphate following ascent to high altitude, while the strong ion difference remained unchanged. They proposed that this increase in weakly dissociated protein anions may account, in part, for the restoration of pH at high altitude. Whilst speculative, these findings support the idea that an altered pH buffering may account for the observed alterations in cerebrovascular and ventilatory responsiveness to CO2 following ascent to high altitude. The role of altered acid–base balance in cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and ventilatory control, either via renal compensation or altered weakly dissociated protein anion following ascent to high altitude, clearly warrants further investigation.

Enhanced cerebrovascular reactivity to hypocapnia with initial exposure to 5050 m

In contrast to the current study, we had previously reported that hypocapnic cerebrovascular reactivity was either blunted (Ainslie et al. 2008) or unchanged (Ainslie & Burgess, 2008) at 3840 m following ∼9 days at a higher altitude (>5000 m) compared to low altitude (1400 m). Moreover, it has been shown recently that a blunted hypocapnic cerebrovascular reactivity may play an important role in the pathogenesis of central sleep apnoea, by narrowing the difference between eupnoeic  and the apnoeic threshold (Xie et al. 2009). In a cross-sectional study, Jansen et al. (1999) reported a higher cerebrovascular reactivity to hypocapnia (

and the apnoeic threshold (Xie et al. 2009). In a cross-sectional study, Jansen et al. (1999) reported a higher cerebrovascular reactivity to hypocapnia ( ∼22 mmHg for ≥ 5 min) in healthy newcomers to high altitude (4243 m) compared to sea-level controls (n= 47) (Jansen et al. 1999). An important limitation of that study was that CBF was obtained over a non-steady-state period of 5–7 s (four to five cardiac cycles) using a hand-held probe, a procedure very prone to measurement artefacts that result in unreliable MCAv recordings. Nevertheless, the authors proposed that this augmented hypocapnic cerebrovascular reactivity could potentially be explained by a resetting of the total cerebral vasomotor reactivity (the sum of the fractional dilatation during hypercapnia and the fractional vasoconstriction during hypocapnia). Consistent with their findings (Jansen et al. 1999), we observed an 115% increase in the MCAv response during hypocapnia (voluntary hyperventilation) at 5050 m in the current study (Fig. 3).

∼22 mmHg for ≥ 5 min) in healthy newcomers to high altitude (4243 m) compared to sea-level controls (n= 47) (Jansen et al. 1999). An important limitation of that study was that CBF was obtained over a non-steady-state period of 5–7 s (four to five cardiac cycles) using a hand-held probe, a procedure very prone to measurement artefacts that result in unreliable MCAv recordings. Nevertheless, the authors proposed that this augmented hypocapnic cerebrovascular reactivity could potentially be explained by a resetting of the total cerebral vasomotor reactivity (the sum of the fractional dilatation during hypercapnia and the fractional vasoconstriction during hypocapnia). Consistent with their findings (Jansen et al. 1999), we observed an 115% increase in the MCAv response during hypocapnia (voluntary hyperventilation) at 5050 m in the current study (Fig. 3).

Implications

The MCAv CO2 reactivity estimated in the current study was similar in the hypercapnic and hypocapnic range at high altitude, while previous studies have reported a lower cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity during hypocapnia than hypercapnia (Xie et al. 2005; Peebles et al. 2007). From a teleological perspective, however, the ‘normal’ lower reactivity in the hypocapnic range compared to the hypercapnic range might be a protective mechanism to prevent cerebral ischaemia during transient drops in  , which are known to occur in a range of physiological (postural change, exercise) and pathophysiological (asthma, syncope, sleep apnoea, congestive heart failure, anxiety attacks) situations. Our findings indicate that this protective response to hypocapnia might be altered at high altitude (Fig. 4). The extent to which such changes in hypocapnic cerebrovascular reactivity may be a cause or consequence of neurological injury is unclear (Wilson et al. 2009). Therefore, the mechanism by which high altitude may alter intracranial vascular tone warrants further investigation. Nevertheless, an enhanced cerebrovascular responsiveness to hypocapnia would increase an individual's risk of cerebral ischaemia during reductions in

, which are known to occur in a range of physiological (postural change, exercise) and pathophysiological (asthma, syncope, sleep apnoea, congestive heart failure, anxiety attacks) situations. Our findings indicate that this protective response to hypocapnia might be altered at high altitude (Fig. 4). The extent to which such changes in hypocapnic cerebrovascular reactivity may be a cause or consequence of neurological injury is unclear (Wilson et al. 2009). Therefore, the mechanism by which high altitude may alter intracranial vascular tone warrants further investigation. Nevertheless, an enhanced cerebrovascular responsiveness to hypocapnia would increase an individual's risk of cerebral ischaemia during reductions in  and potentially may lead to impairment in cognitive function at high altitude (Hornbein et al. 1989).

and potentially may lead to impairment in cognitive function at high altitude (Hornbein et al. 1989).

In summary, findings from the present study demonstrate, for the first time, that both the cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and the central chemoreflex are enhanced following ascent to high altitude. Our data provide evidence to support the notion that arterial [H+], and presumably arterial wall [H+] may be the main determinant of CBF rather than  . Therefore, it appears that an altered acid–base balance may account, in part, for the observed increase in cerebrovascular and ventilatory responsiveness to CO2 following ascent to high altitude.

. Therefore, it appears that an altered acid–base balance may account, in part, for the observed increase in cerebrovascular and ventilatory responsiveness to CO2 following ascent to high altitude.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to Prof. J. Duffin who kindly provided his technical assistance and the rebreathing analysis program. Special thanks to our participants for giving up their time for this study. We extend our thanks to ADInstruments and Compumedics Ltd for the use of their laboratory equipment. This study was supported by the Otago Medical Research Foundation, SPARC New Zealand, the Peninsula Health Care p/l and Air Liquide p/l. This study was carried out within the framework of the Ev-K2-CNR Project in collaboration with the Nepal Academy of Science and Technology as foreseen in the Memorandum of Understanding between Nepal and Italy, and we thank the Italian National Research Council for their contribution.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- CVCi

cerebrovascular conductance index

- MCAv

middle cerebral artery velocity

- MAP

mean arterial blood pressure

- SBE

standard basic excess

ventilation

Authors contributions

All the authors were involved in the conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published.

References

- Aaslid R, Markwalder TM, Nornes H. Noninvasive transcranial Doppler ultrasound recording of flow velocity in basal cerebral arteries. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:769–774. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.57.6.0769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN, Barach A, Murrell C, Hamlin M, Hellemans J, Ogoh S. Alterations in cerebral autoregulation and cerebral blood flow velocity during acute hypoxia: rest and exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H976–983. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00639.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN, Burgess KR. Cardiorespiratory and cerebrovascular responses to hyperoxic and hypoxic rebreathing: effects of acclimatization to high altitude. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;161:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN, Duffin J. Integration of cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and chemoreflex control of breathing: mechanisms of regulation, measurement, and interpretation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R1473–1495. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.91008.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN, Ogoh S, Burgess K, Celi L, McGrattan K, Peebles K, Murrell C, Subedi P, Burgess KR. Differential effects of acute hypoxia and high altitude on cerebral blood flow velocity and dynamic cerebral autoregulation: alterations with hyperoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:490–498. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00778.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaber AP, Hartley T, Pretorius PJ. Effect of acute exposure to 3660 m altitude on orthostatic responses and tolerance. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:591–601. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00749.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess K, Fan JL, Peebles KC, Thomas K, Lucas S, Lucas RA, Dawson A, Swart M, Shepherd K, Ainslie P. Exacerbation of obstructive sleep apnea by oral indomethacin. Chest. 2010 doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1329. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RW, Santiago TV, Edelman NH. Effects of graded reduction of brain blood flow on chemical control of breathing. J Appl Physiol. 1979;47:1289–1294. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1979.47.6.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claassen JA, Zhang R, Fu Q, Witkowski S, Levine BD. Transcranial Doppler estimation of cerebral blood flow and cerebrovascular conductance during modified rebreathing. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:870–877. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00906.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham DJ, Hey EN, Patrick JM, Lloyd BB. The effect of noradrenaline infusion on the relation between pulmonary ventilation and the alveolar PO2 and PCO2 in man. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1963;109:756–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1963.tb13504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey JA, Forster HV, DoPico GA. Ventilatory acclimatization to moderate hypoxemia in man. The role of spinal fluid (H+ J Clin Invest. 1974;53:1091–1100. doi: 10.1172/JCI107646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffin J, Mohan RM, Vasiliou P, Stephenson R, Mahamed S. A model of the chemoreflex control of breathing in humans: model parameters measurement. Respir Physiol. 2000;120:13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster HV, Dempsey JA, Chosy LW. Incomplete compensation of CSF [H+] in man during acclimatization to high altitude (4,300 m) J Appl Physiol. 1975;38:1067–1072. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.38.6.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner WN. The pattern of breathing following step changes of alveolar partial pressures of carbon dioxide and oxygen in man. J Physiol. 1980;300:55–73. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbein TF, Townes BD, Schoene RB, Sutton JR, Houston CS. The cost to the central nervous system of climbing to extremely high altitude. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1714–1719. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198912213212505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen GF, Krins A, Basnyat B. Cerebral vasomotor reactivity at high altitude in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:681–686. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.2.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindegaard KF, Lundar T, Wiberg J, Sjoberg D, Aaslid R, Nornes H. Variations in middle cerebral artery blood flow investigated with noninvasive transcranial blood velocity measurements. Stroke. 1987;18:1025–1030. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.6.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahamed S, Cunningham DA, Duffin J. Changes in respiratory control after three hours of isocapnic hypoxia in humans. J Physiol. 2003;547:271–281. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahamed S, Duffin J. Repeated hypoxic exposures change respiratory chemoreflex control in humans. J Physiol. 2001;534:595–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00595.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew L, Gopinath PM, Purkayastha SS, Sen Gupta J, Nayar HS. Chemoreceptor sensitivity in adaptation to high altitude. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1983;54:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milledge JS, Sorensen SC. Cerebral arteriovenous oxygen difference in man native to high altitude. J Appl Physiol. 1972;32:687–689. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.32.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan R, Duffin J. The effect of hypoxia on the ventilatory response to carbon dioxide in man. Respir Physiol. 1997;108:101–115. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(97)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan RM, Amara CE, Cunningham DA, Duffin J. Measuring central-chemoreflex sensitivity in man: rebreathing and steady-state methods compared. Respir Physiol. 1999;115:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(99)00003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller K, Paulson OB, Hornbein TF, Colier WN, Paulson AS, Roach RC, Holm S, Knudsen GM. Unchanged cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism after acclimatization to high altitude. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:118–126. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200201000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peebles K, Celi L, McGrattan K, Murrell C, Thomas K, Ainslie PN. Human cerebrovascular and ventilatory CO2 reactivity to end-tidal, arterial and internal jugular vein PCO2. J Physiol. 2007;584:347–357. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.137075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichmuth KJ, Dopp JM, Barczi SR, Skatrud JB, Wojdyla P, Hayes D, Jr, Morgan BJ. Impaired vascular regulation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: Effects of CPAP treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0393OC. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SB, Guleria JS, Khanna PK, Talwar JR, Manchanda SC, Pande JN, Kaushik VS, Subba PS, Wood JE. Immediate circulatory response to high altitude hypoxia in man. Nature. 1968;217:1177–1178. doi: 10.1038/2171177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahn SA, Zwillich CW, Dick N, McCullough RE, Lakshminarayan S, Weil JV. Variability of ventilatory responses to hypoxia and hypercapnia. J Appl Physiol. 1977;43:1019–1025. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1977.43.6.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoene RB, Roach RC, Hackett PH, Sutton JR, Cymerman A, Houston CS. Operation Everest II: ventilatory adaptation during gradual decompression to extreme altitude. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990;22:804–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secher NH, Seifert T, Van Lieshout JJ. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism during exercise: implications for fatigue. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:306–314. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00853.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severinghaus JW, Mitchell RA, Richardson BW, Singer MM. Respiratory control at high altitude suggesting active transport regulation of Csf Ph. J Appl Physiol. 1963;18:1155–1166. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1963.18.6.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi RB, Preiss D, Vesely A, Fisher JA, Duffin J. Changes in respiratory control after 5 days at altitude. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2005;145:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vovk A, Cunningham DA, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH, Duffin J. Cerebral blood flow responses to changes in oxygen and carbon dioxide in humans. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;80:819–827. doi: 10.1139/y02-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiskopf RB, Gabel RA, Fencl V. Alkaline shift in lumbar and intracranial CSF in man after 5 days at high altitude. J Appl Physiol. 1976;41:93–97. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1976.41.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MH, Newman S, Imray CH. The cerebral effects of ascent to high altitudes. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:175–191. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie A, Skatrud JB, Barczi SR, Reichmuth K, Morgan BJ, Mont S, Dempsey JA. Influence of cerebral blood flow on breathing stability. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:850–856. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90914.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie A, Skatrud JB, Khayat R, Dempsey JA, Morgan B, Russell D. Cerebrovascular response to carbon dioxide in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:371–378. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-807OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie A, Skatrud JB, Morgan B, Chenuel B, Khayat R, Reichmuth K, Lin J, Dempsey JA. Influence of cerebrovascular function on the hypercapnic ventilatory response in healthy humans. J Physiol. 2006;577:319–329. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.110627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]