Abstract

Objectives

To examine the association between Helicobacter pylori infection and non-ulcer dyspepsia, and to assess the effect of eradicating H pylori on dyspeptic symptoms in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis of (a) observational studies examining the association between Helicobacter pylori infection and non-ulcer dyspepsia (association studies), and (b) therapeutic trials examining the association between eradication of H pylori and dyspeptic symptoms in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia (eradication trials).

Data sources

Randomised controlled trials and observational studies conducted worldwide and published between January 1983 and March 1999.

Main outcome measures

Summary odds ratios and summary symptom scores.

Results

23 association studies and 5 eradication trials met the inclusion criteria. In the association studies the summary odds ratio for H pylori infection in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia was 1.6 (95% confidence interval 1.4 to 1.8). In the eradication trials the summary odds ratio for improvement in dyspeptic symptoms in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia in whom H pylori was eradicated was 1.9 (1.3 to 2.6).

Conclusions

Some evidence shows an association between H pylori infection and dyspeptic symptoms in patients referred to gastroenterologists. An improvement in dyspeptic symptoms occurred among patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia in whom H pylori was eradicated.

Introduction

Although drugs for acid suppression are the mainstay empirical treatment for ulcer-like dyspeptic symptoms1–3 controversy surrounds the role of empirical eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori.4,5 Although there is strong evidence of an association between H pylori infection, chronic gastritis, and peptic ulcer disease,6,7 the relation between dyspeptic symptoms and gastritis caused by H pylori is not well described.8,9 Systematic reviews examining the relation between non-ulcer dyspepsia and H pylori have based their conclusions on qualitative assessments of selected articles10–15 without any quantitative summary estimate of an association. Only one estimate for H pylori infection among patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia has been quoted in the literature,16 but this was not based on a systematic selection of articles, no sensitivity analyses of the estimate were included, and there was no assessment for statistical heterogeneity.

If primary care strategies are to be developed for managing non-ulcer dyspepsia or dyspeptic symptoms then evidence needs to be firmly established for a relation between non-ulcer dyspepsia and H pylori infection and for an improvement in dyspeptic symptoms with eradication of H pylori.

We aimed to review the literature for both observational studies and therapeutic trials. We also aimed to provide quantitative summary estimates for an association between H pylori infection and non-ulcer dyspepsia and for change in dyspeptic symptoms in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia in whom H pylori was eradicated.

Methods

Identification of studies

We conducted a Medline search of non-review articles in English from January 1983 to March 1999 with the MeSH headings “dyspepsia,” “non-ulcer dyspepsia,” “gastritis,” “Helicobacter pylori,” and “Campylobacter pylori.”

Study eligibility was assessed by RLJ and EB who independently reviewed all 654 abstracts. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. On the basis of the abstract, specific criteria were used to retrieve observational studies examining the association between H pylori and non-ulcer dyspepsia (association studies). These criteria included a description of a patient or patient group and a control or non-diseased group and an indication that dyspepsia, non-ulcer dyspepsia, or symptoms of dyspepsia was a separate outcome of the study. The study designs were of a prevalence, case-control, or cohort type.

Similarly, abstracts from studies examining H pylori eradication and dyspeptic symptoms were retrieved using predefined criteria. These criteria included the symptoms of dyspepsia defined as an outcome measure of the study, all subjects with non-ulcer dyspepsia or dyspeptic symptoms who harboured H pylori, and treatment modalities that have shown some efficacy in the eradication of H pylori. Only randomised trials were included.

Data extraction

We assessed the association studies with a modified version of a quality assessment form for observational studies,17 and we assessed the H pylori eradication trials with an existing quality assessment system for clinical trials.18 The methods sections were cut out and coded so that the assessors were blind to the study results, title, authors, publication date, and journal. Agreement between the assessors was evaluated with the κ statistic.19,20

Data from all articles were abstracted by RLJ and EB independently. The results sections were cut out and coded so that the assessors were blind to the methods, title, authors, publication date, and journal. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. For each association study the number of subjects with non-ulcer dyspepsia or dyspeptic and control subjects with or without H pylori infection were extracted from each study and entered into 2×2 tables. The eradication trials gave the number of subjects with improvement in dyspeptic symptoms and those with no improvement or worsening symptoms both for those in whom H pylori was eradicated and for those in whom it was not. This allowed the construction of 2×2 tables.

Statistical analysis

We calculated an overall point estimate of the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval with the Mantel-Haenszel statistic,21 which is based on the assumption of a fixed effect model.22 Homogeneity was assessed with the Breslow-Day method.23 The data were entered and analysed with a statistical package.24

Results

The review of abstracts identified 84 potentially eligible studies. Thirty five were eliminated because they did not satisfy the retrieval criteria. This left 26 articles dealing with the association between H pylori infection and non-ulcer dyspepsia (association studies) and 23 articles examining dyspeptic symptoms in relation to H pylori eradication therapy (eradication trials).

Observational association studies

Study characteristics and quality scores

Three studies did not provide information on H pylori infection in the control group and could not be included in the pooled analysis. The box summarises the study characteristics of the 23 association studies (see website). Many studies defined non-ulcer dyspepsia as upper abdominal pain or discomfort with no organic disease identified (16 studies) lasting more than 4 weeks.12 Most studies included patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia referred to a specialty or gastroenterology clinic16 and based the H pylori assessment on the results of endoscopic biopsy.15 The rate of H pylori infection in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia was 55.2% (range 9.4 (18.4) to 87.5) and in controls was 40.4% (range 4.7 (22.3) to 83.3).

Study characteristics (number of trials) of the 23 association studies

Case selectionReferred cases (16)w1 w2 w4 w5 w8-w12 w14-w20

Random community sample (4)w7 w13 w21 w23

Control selection

Hospital based (4)w4 w5 w11 w16

Community based (13)w1 w3 w6 w8-w10 w12 w14 w15 w18-w20 w22

Random community sample (4)w7 w13 w21 w23

H pylori assessment

Serology (7)w1-w3 w6 w7 w22 w23

Urea breath test (1)w9

Endoscopically obtained biopsy (15)w4 w5 w8 w10-w21

Definition of non-ulcer dyspepsia

Duration more than 4 weeks (12)w1 w2 w4-w6 w8-w11 w13-w15 w18-w22

No organic disease found on investigation (16)w1 w4-w6 w8-w11 w13-w15 w18-w22

Upper abdominal or epigastric pain or discomfort (16)w1 w2 w4-w7 w11-w18 w21 w22

Symptoms related to meals (9)w1 w4-w6 w11 w12 w14 w15 w18

Other symptoms such as heartburn, nausea, or vomiting (12)w2 w5-w7 w12-w15 w17 w18 w21 w23

Not defined (5)w3 w8 w10 w19 w20

Exclusion criteria

History of:Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (6)w3 w5 w6 w12 w14 w15Peptic ulcer disease (9)w3 w8 w9 w12-w14 w16 w20 w21Irritable bowel syndrome (5)w4 w6 w7 w12 w15

Concomitant non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (8)w2 w5 w6 w9 w12 w17 w18 w20

Previous eradication therapy for H pylori (8)w2 w3 w5 w11 w12 w15 w16 w18

Out of a possible 100 the mean (SD) quality score for the 23 association studies was 44.2 (11.1), median 41. Most studies lost points on lack of control for confounding and poor definitions of dyspepsia. There was excellent agreement between the two quality assessors (κ=0.84).19

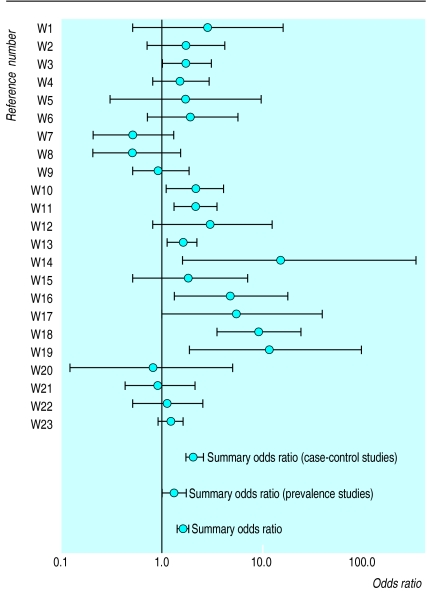

Summary estimates

Figure 1 shows the odds ratios and summary odds ratio for each association study. Twenty three studies were pooled giving a summary odds ratio of 1.6 (95% confidence interval 1.4 to 1.8) for H pylori infection related to non-ulcer dyspepsia (P<0.001). The test for homogeneity was statistically significant (P<0.001). The summary odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for symptoms of abdominal pain (three studies), abdominal distension, flatulence, bloating, or belching (four), and nausea and vomiting (three) were respectively 1.2 (0.96 to 1.4), 1.2 (0.67 to 21.0), and 0.8 (0.4 to1.4). All were statistically non-significant.

Figure 1.

Odds ratios and summary odds ratios for association studies

Sensitivity analysis

The table shows the influence of study design, quality scores, and control of confounders on pooled estimates. Summarised estimates were statistically homogeneous for prevalence studies, studies with quality scores above the median, and studies that controlled for confounding.

Eradication trials

Study characteristics and quality assessment scores

Five eradication trials provided data on change in dyspeptic symptoms in patients in whom H pylori had or had not been eradicated (see website).w24-w28 This change was defined as an improvement, or no change or worsening of dyspeptic symptoms. The 18 other eradication trials could not be included in a pooled analysis because they did not provide data on change in symptoms in relation to H pylori eradication.

Two trials detailed the duration of dyspeptic symptoms. Dyspepsia was defined according to published criteria—pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen in association with other symptoms such as bloating, nausea, or vomiting, relation with meals, worse at night, and reflux. All eradication trials recruited patients from specialty or gastroenterology clinics, and four trials assessed H pylori infection from endoscopically obtained biopsies. Three trials used single regimen therapy, and two trials used triple regimen therapy. The single therapy trials followed patients for less than 8 weeks whereas the triple therapy trials assessed H pylori eradication and change in dyspeptic symptoms at 12 months.

Out of a possible 100 the mean (SD) quality score for the five eradication trials was 48.4 (16.1), median 42. Most studies lost points for no description of randomisation or blinding, no assessment of treatment compliance, and poor presentation of results. There was good agreement between the two quality assessors (κ =0.7).19

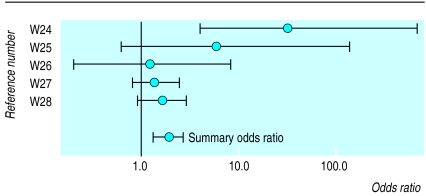

Summary estimates

We compared the change in dyspeptic symptoms in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia in whom H pylori had or had not been eradicated. Figure 2 shows the odds ratios and summary odds ratio for each eradication trial. The odds ratio for symptomatic improvement was 1.9 (1.3 to 2.6) for patients in whom H pylori was eradicated (P=0.001). This estimate was statistically homogeneous (P=0.046).

Figure 2.

Odds ratios and summary odds ratios for eradication trials

Sensitivity analysis

The table shows the influence of H pylori therapeutic regimen and study quality on the summary estimates. The summary odds ratio for single therapy regimens was higher than for triple therapy regimens. Quality scores for the two trials examining triple therapy regimens were above the median as opposed to the three trials examining single therapy regimens.

Discussion

The association studies included in our meta-analysis showed a small yet statistically significant increased risk of non-ulcer dyspepsia in people infected with H pylori. Patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia in whom H pylori was eradicated were almost twice as likely to show an improvement in their dyspeptic symptoms than patients in whom H pylori was not eradicated.

Association studies

The overall summary estimate for the association studies was fairly robust with respect to quality score, the control of confounders, and study design. Interestingly, a higher summary odds ratio was produced from the case-control studies than from the prevalence studies. This may reflect differences in the severity or frequency of dyspeptic symptoms. The prevalence studies utilised structured questionnaires in the general populations to identify subjects with non-ulcer dyspepsia whereas the case-control studies identified such subjects from patients seeking medical treatment. The risk of H pylori infection increases with advancing age, lower occupational status, and lower socioeconomic status,25 and controlling for these factors should reduce the heterogeneity of summary estimates. Statistical heterogeneity was reduced among association studies that controlled for confounding and also among studies with quality scores above the median. The design of the association study did not explain statistical heterogeneity.

Eradication regimens

Triple regimen therapies are the currently accepted treatment for H pylori eradication.26 Although the number of trials in the sensitivity analysis was small, pooling the triple regimens produced a lower summary odds ratio than the single therapy regimens (see table). Although H pylori eradication was achieved at the time improvements in dyspeptic symptoms were assessed the magnitude of this improvement may have been affected by the regimens used. Colloidal bismuth salicylate is known to improve symptoms irrespective of H pylori infection, as does omeprazole.27,28 The triple regimens were also used in trials with higher quality scores and longer follow up intervals. Perceived improvements in dyspeptic symptoms may decrease over time and this may explain the lower estimate in the triple than single regimen trials. Therefore, the type of regimen used, the duration of follow up, and the quality of the trial limits the generalisability of this estimate. Further trials that use currently acceptable eradication regimens and that monitor dyspeptic symptoms over longer time intervals are required.

Definitions

Dyspepsia

Inconsistent definitions of dyspepsia may contribute to the conflicting evidence provided by trials of H pylori eradication. The definition of dyspepsia has been refined over the years to represent pain or discomfort centred in the upper abdomen described as bloating, distension, fullness, or nausea but not acid regurgitation or heartburn.29 These symptoms should be present for at least a month. Dyspeptic symptoms have generally been poor in discriminating functional from organic disease.30,31 Non-ulcer dyspepsia refers to the presence of dyspeptic symptoms in the absence of an identifiable organic disease.32 Depending on the symptoms used to define dyspeptic patients the benefits of treatments may be either augmented or diminished.33

Symptoms and scores

Similarly, different symptoms and scores have been used to assess treatment response in trials of H pylori eradication. Although virtually all scores include upper abdominal pain or discomfort there are a variety of other symptoms included. Likert scales are subject to different interpretations by respondents, leading to misclassification bias.34 In addition to this the weights of scales used in the trials of H pylori eradication ranged from three to seven levels. Validated dyspeptic symptom scores would enable comparisons between different treatment modalities assessed in trials, including trials of H pylori eradication.

Limitations

Meta-analyses have their limitations.35–37 Publication bias tends to lead to the inclusion of studies that only show a positive result. There are limitations to Medline searches as our search failed to identify 16 articles, which were found only when searching the references of papers. A potential for a selection bias exists since the studies included in our meta-analysis did not include information published in textbooks, non-English language articles, and abstract only publications.

Our estimate is slightly lower than the only other quoted one for H pylori infection and non-ulcer dyspepsia (2.3, 1.9 to 2.7).16 Several reasons may explain the difference. Firstly, we included 23 rather than 19 articles with our estimate. Secondly, we restricted the article selection to those published in the English language only whereas the other estimate included two non-English language studies and one abstract. Finally, we selected articles in a systematic manner and evaluated them for methodological quality, and we undertook sensitivity analyses and estimated statistical heterogeneity; none of which was completed in the other study.

What is already known on this topic

Although infection with Helicobacter pylori is strongly associated with peptic ulcer disease the relation with non-ulcer dyspepsia is controversial

The adoption of empirical eradication regimens for non-ulcer dyspepsia is difficult given the little information about their efficacy

Recently published randomised controlled trials allow an estimation of the change in dyspeptic symptoms among patients

What this paper adds

This meta-analysis found a small yet statistically significant relation between H pylori infection and non-ulcer dyspepsia

Eradication of H pylori was associated with an almost twofold improvement in dyspeptic symptoms among patients referred to specialty clinics

This quantitative estimate may be used in primary care trials to determine the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of empirical eradication of H pylori in non-ulcer dyspepsia

Most of the association studies and all the eradication trials recruited patients from secondary or tertiary care populations, therefore the findings may not be generalisable to primary care patients who have less severe disease and symptoms.38 Although eradication therapy for H pylori may be beneficial for patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia seen either in specialty clinics or by gastroenterologists this magnitude of symptomatic improvement may not be seen in primary care patients. Only a randomised trial of patients seen and managed by primary care physicians would solve this problem.

In addition, both the clinical and economic costs of H pylori eradication need to be considered. Metronidazole resistance is found worldwide, with resistance rates of over 70% in developing nations.39,40 Resistance rates for clarithromycin approach 10%.41 There is preliminary evidence of a protective association between H pylori infection and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease,42 with a reduction in efficacy of proton pump inhibitors after cure of H pylori.43 Although H pylori eradication is cost effective for patients with peptic ulcer disease,44,45 the economic benefits in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia is equivocal.46–48

Conclusions

A quantitative estimate gives a sense of the magnitude of the relation between a risk factor and a disease. We found that people infected with H pylori are about one and a half to twice as likely to have non-ulcer dyspepsia compared with controls. Eradicating H pylori results in almost a twofold improvement in dyspeptic symptoms. It is not yet known whether the magnitude of these estimates is large enough to influence clinical guidelines or clinicians, but the summary effect size estimates from our meta-analysis could help with sample size calculations for future studies. Such studies should include primary care patient populations where the efficacy of empirical therapy for dyspeptic patients with H pylori infection may be examined.

Supplementary Material

Table.

Sensitivity analysis of trials of Helicobacter pylori and non-ulcer dyspepsia that met inclusion criteria for meta-analysis

| Pooled group | No of studies | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Association studies | |||

| Summary estimate | 23 | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) | <0.001 |

| Study design: | |||

| Prevalence | 5 | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7) | 0.095 |

| Case-control | 17 | 2.0 (1.7 to 2.5) | 0.002 |

| Quality score: | |||

| >Median | 12 | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.8) | 0.068 |

| <Median | 11 | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.9) | <0.001 |

| Controlled for confounders | 7 | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.6) | 0.05 |

| Eradication trials | |||

| Summary estimate | 5 | 1.9 (1.3 to 2.6) | 0.046 |

| Treatments: | |||

| Single regimen | 3 | 15.4 (2.2 to 16.7) | 0.12 |

| Triple regimen | 2 | 1.4 (1.0 to 2.3) | 0.70 |

Footnotes

Funding: The Adam Linton fellowship is sponsored by the Ontario Medical Association.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Zar S, Mendall MA. Clinical practice—strategies for management of dyspepsia. Br Med Bull. 1998;54:217–228. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talley NJ. Modern management of dyspepsia. Aust Fam Physician. 1996;25:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiba N, Hunt RH, Goeree R, O’Brien BJ, Bernard L. A Canadian physician survey of dyspepsia management. Can J Gastroenterol. 1998;12:83–90. doi: 10.1155/1998/175926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talley NJ. What role does Helicobacter pylori play in dyspepsia and non-ulcer dyspepsia? Arguments for and against H. pylori being associated with dyspeptic symptoms. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(suppl 6):67–77S. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)80016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis S. Triple therapy and Helicobacter pylori. Aust Fam Physician. 1996;25:53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institutes of Health. Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. NIH Consensus Statement. 1994;12:1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soll AH. Medical treatment of peptic ulcer disease. Practice guidelines. JAMA. 1996;275:622–629. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.8.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel P, Khulusi S, Mendall MA, Lloyd R, Jazrawi R, Maxwell JD, et al. Prospective screening of dyspeptic patients by Helicobacter pylori serology. Lancet. 1995;346:1315–1318. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czinn SJ, Bertram TA, Murray PD, Yand P. Relationship between gastric inflammatory response and symptoms in patients infected with Helicobacter pylori. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26(suppl 181):33–37. doi: 10.3109/00365529109093205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJO, Sherman PM. Helicobacter pylori infection as a cause of gastritis, duodenal ulcer, gastric cancer and nonulcer dyspepsia: a systematic overview. Can Med Assoc J. 1994;150:177–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talley NJ. A critique of therapeutic trials in Helicobacter pylori—positive functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1174–1183. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJO. A systematic overview (meta-analysis) of outcome measures in Helicobacter pylori gastritis trials and functional dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28(suppl 199):40–43. doi: 10.3109/00365529309098356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Cleary C, Talley NJ, Peterson TC, Nyren O, Bradley LA, et al. Drug treatment of functional dyspepsia: a systematic analysis of trial methodology with recommendations for design of future trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:660–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Morain C, Gilvarry J. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28(suppl 196):30–33. doi: 10.3109/00365529309098340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJO, Sherman PM. Indications for treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: a systematic overview. Can Med Assoc J. 1994;50:189–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong D. Helicobacter pylori infection and dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31(suppl 215):38–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabriel SE, Jaakkimainen L, Bombardier C. Risk for serious gastrointestinal complications related to use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:787–796. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-10-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chambers TC, Smith H, Jr, Blackburn B, Silverman B, Schroeder B, Reitman D, et al. A method for assessing the quality of a randomized control trial. Controlled Clin Trials. 1981;2:31–49. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(81)90056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd edn. New York: Wiley; 1981. p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Analytical Software. Statistix for Windows. Tallahassee, FL: Borland International; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Institute. 1959;22:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Toronto: Academic Press; 1985. Parametric estimation of effect size from a series of experiments; pp. 107–145. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petitti DB. Monographs in epidemiology and biostatistics. Vol. 24. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994. Meta-analysis decision analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis. Methods for quantitative synthesis in medicine; pp. 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Cochrane Collaboration. Review manager, version 4.0 for Windows. Oxford: The Cochrane Collaboration; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malaty HM, Kim JG, Kim SD, Graham DY. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korean children: inverse relation to socioecomonic status despite a uniformly high prevalence in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:257–262. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiba N, Rao BV, Rademaker JW, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of antibiotic therapy in eradicating Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1716–1727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goves J, Oldring JK, Kerr D, Dallara RG, Roffe EJ, Powell JA, et al. First line treatment with omeprazole provides an effective and superior alternative strategy in the management of dyspepsia compared to antacid/alginate liquid: a multicentre study in general practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:147–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.0284f.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phull PS, Halliday D, Price AB, Jacyna MR. Absence of dyspeptic symptoms as a test for Helicobacter pylori eradication. BMJ. 1996;312:349–350. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7027.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talley NJ, Colin-Jones D, Koch KL, Koch M, Nyren O, Stanghellini V. Functional dyspepsia: a classification with guidelines for diagnosis and management. Gastroenterol Int. 1991;4:145–160. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Tesmer DL, Zinsmeister AR. Lack of discriminant value of dyspepsia subgroups in patients referred for upper endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1378–1386. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90142-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mansi C, Savarino V, Mela GS, Picciotto A, Mele MR, Celle G. Are clinical patterns of dyspepsia a valid guideline for appropriate use of endoscopy? A report on 2253 dyspeptic patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1011–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heatley RV, Rathborne BJ. Dyspepsia: a dilemma for doctors? Lancet. 1987;332:779–781. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92509-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson WG. Dyspepsia: is a trial of therapy appropriate? Can Med Assoc J. 1995;153:293–299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDowell I, Newell C. Measuring health. A guide to rating scales and questionnaires. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1987. pp. 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Egger M, Davey Smith G. Meta-analysis bias in location and selection of studies. BMJ. 1998;316:61–66. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7124.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stern JM, Simes RJ. Publication bias: evidence of delayed publication in a cohort study of clinical research projects. BMJ. 1997;315:640–645. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davey Smith G, Egger M. Meta-analysis: unresolved issues and future developments. BMJ. 1998;316:221–225. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7126.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warndorff DK, Knottnerus JA, Huijnen LGJ, Starmans R. How well do general practitioners manage dyspepsia? J Roy Coll Gen Pract. 1989;39:499–502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alarcon T, Domingo D, Lopez-Brea M. Antibiotic resistance problems with Helicobacter pylori. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999;12:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(99)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoffman PS. Antibiotic resistance mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori. Can J Gastroenterol. 1999;13:243–249. doi: 10.1155/1999/838072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ducons JA, Santolaria S, Guirao R, Ferrero M, Montoro M, Gomollon F. Impact of clarithromycin resistance on the effectiveness of a regimen for Helicobacter pylori: a prospective study of 1-week lansoprazole, amoxycillin and clarithromycin in active peptic ulcer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:775–780. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu JC, Sung JJ, Ng EK, Go MY, Chan WB, Chan FK, et al. Prevalence and distribution of Helicobacter pylori in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a study from the East. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1790–1794. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Connor HJ. Review article: Helicobacter pylori and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease—clinical implications and management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:117–127. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fendrick AM, McCort JT, Chernew ME, Hirth RA, Patel C, Bloom BS. Immediate eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with previously documented peptic ulcer disease: clinical and economic effects. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2017–2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Brien B, Goeree R, Hunt R, Wilkinson J, Levine M, William A. Cost effectiveness of alternative Helicobacter pylori eradication strategies in the management of duodenal ulcer. Can J Gastroenterol. 1997;11:323–331. doi: 10.1155/1997/290183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sonneberg A. Cost-benefit analysis of testing for Helicobacter pylori in dyspeptic subjects. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1773–1777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ebell MH, Warbasse L, Brenner C. Evaluation of the dyspeptic patient: a cost-utility study. J Fam Pract. 1997;44:545–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ofman JJ, Etchason J, Fullerton S, Kahn KL, Soll AH. Management of strategies for Helicobacter pylori-seropositive patients with dyspepsia: clinical and economic consequences. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:280–291. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-4-199702150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.