Abstract

Background

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is a common disorder that remains underdiagnosed in adult females. The Berlin Questionnaire is a validated tool for identifying people at risk for OSAS. The aim of this report was to evaluate the prevalence of common symptoms of OSAS in women and to estimate the risk for OSAS among females in the United States.

Methods

This is an analysis of data from the 2007 Sleep in America Poll of the National Sleep Foundation. The NSF Poll is an annual telephone survey of a representative sample of U.S. adults. The 2007 NSF Poll included 1254 women in the United States, with an oversample of pregnant and postpartum women. We used the Berlin Questionnaire to estimate the risk for OSAS among the U.S. female population. This instrument includes questions about self-reported snoring, witnessed apneas, daytime sleepiness, hypertension, and obesity. Also included were questions about sleep habits, sleep problems, menstrual cycle status, and other medical disorders.

Results

Twenty-five percent of the female population was found to be at high risk for OSAS. Among women at high risk, such common symptoms of OSAS as habitual snoring (61%), observed apneas (7%), and daytime sleepiness (24%) were highly prevalent. Sleep onset insomnia (32%) or maintenance insomnia symptoms (19%) and restless legs syndrome (RLS) symptoms (33%) or body movements (60%) also were frequently reported. The risk increased with age (p < 0.05), obesity (p < 0.001), and menopause (p < 0.001). The presence of chronic medical disorders was more frequently reported among women at high risk.

Conclusions

One in four women in America is at high risk of having OSAS. Awareness by the primary care medical community of this disorder in females should thus be increased.

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), a spectrum of disorders, is characterized by a snoring history and repetitive obstructions of the upper airway leading to sleep fragmentation and excessive daytime sleepiness.1 The least severe disorder of the spectrum is the upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS), characterized by repetitive increases in upper airway resistance not leading to apnea but having similar clinical presentation to snoring and daytime sleepiness.2

For about two decades after OSAS was first described, reports on the prevalence of snoring and sleep apnea suggested that these conditions were uncommon in the female population.3–6 More recently, epidemiological studies have reported that OSAS affects men in a 2-fold higher prevalence than women (4% vs. 2%).1,7 General population-based studies1,7–9 have shown that the prevalence of OSAS in females is higher than the prevalence reported by clinic-based population studies.3,4,5,10 This could be explained by differences in the clinical presentation of symptoms or a selection bias by the referring physicians.8,11 Examining the entire sleep apnea spectrum (OSAS and UARS) may decrease the difference in prevalence between males and females to 1.5:1, as it seems that UARS is more common among women.12 Reasons for gender-related differences are not fully explained; possible explanations include differences in upper airway anatomy,12 collapsibility, and resistance13 and differences of hormonal influence on upper airway dilator muscle activity.9

It has been suggested that only 10% of the U.S. population has been appropriately screened for the presence of OSAS.14 Moreover, it was estimated that >90% of women with sleep apnea may be undiagnosed.14 OSAS is a condition linked to high morbidity and mortality in both men and women.15 Thus, it is crucial to increase the awareness of the medical community about the high prevalence of OSAS in women.

In this report, we investigated self-reported symptoms of sleep apnea and estimated the risk for OSAS in females in a large sample representative of the U.S. population. We also investigated the association of high risk for OSAS in women with such known risk factors as age, obesity, hormonal status, and pregnancy, as well as the relationship of the risk for sleep apnea with common medical disorders.

Material and Methods

The analysis in this report is based on data provided from the 2007 National Sleep Foundation (NSF) annual Sleep in America Poll. The NSF is an independent, nonprofit organization. The questions used in the Poll are selected by an independent task force, and there is no commercial or industry influence on this Poll. The 2007 Poll surveyed sleep habits and sleep disorders in women in the United States.

A total of 1254 telephone interviews were conducted among a random sample of women aged 18–64, between September 12 and October 28, 2006. Quotas were established by region, with pregnant (n = 150) and postpartum women (n = 151) being oversampled. All households surveyed were within the continental United States. The survey averaged 23 minutes in length. A random sample of telephone numbers was purchased from SDR Consulting Inc. (Atlanta, GA). The data were weighted to reflect equal proportions of respondents by age and geographic distribution based on the U.S. Census.

The response rate for this study was 20% (number of completed interviews divided by the number of completed interviews plus the number of contacted households who refused participation or did not complete appointments, factored by the overall incidence of 69%). We used a combination of listed and random digit dial (RDD) sample, with an oversampling of pregnant and postpartum women (meaning we purchased additional sample targeted for these groups). We then set quotas based on population by the four Census regions of the United States.

The Berlin Questionnaire is a simple epidemiological instrument. It is a tool for identification of subjects who are at high risk for OSAS based on snoring behavior, daytime sleepiness, obesity, and hypertension.16 The questionnaire was developed in 1996 and has been validated in a community survey. It was found that the Berlin Questionnaire could predict a respiratory disturbance index (RDI) >5 with a sensitivity of 0.86, a specificity of 0.77, and a positive predictive value of 0.89.17 For higher levels of RDI, its sensitivity decreases to 0.54 for RDI >15 and 0.17 for RDI >30, but its specificity increases to 0.97 for both higher RDI levels.

The questionnaire is divided into three sections. Section 1 includes questions about snoring frequency and loudness and also the presence of witnessed cessations of breathing during sleep. In the second section, subjects are asked how often they have daytime sleepiness after sleep and whether they feel drowsy when they are driving a car. Section 3 includes information about weight and height in order to calculate the body mass index (BMI), as well as personal history of hypertension. A section is considered positive if there are two affirmative answers in sections 1 and 2 or one affirmative answer in section 3. Subjects who have positive scores in two of the three sections are classified as having high risk for OSAS.

The original article on the Berlin Questionnaire did not go into details about the exact wording of the questions. The questions used in the Poll were slightly different from those in versions of the questionnaire used in previous studies. In the published versions of the questionnaire assessing daytime sleepiness, the term “tired” was used to assess sleepiness in the daytime, whereas the NSF questionnaire used the term “sleepiness during the day so badly that it interferes with your daily activities.” It was thought that the term “tired” was not specific enough and might have been positive for people with chronic diseases not related to sleep disorders. Also, the NSF modification of the questionnaire was more specific regarding frequency of driving drowsy and the presence of obesity (BMI was actually calculated rather than asking only whether weight had changed). The questions from the Berlin Questionnaire that were used in the analysis of this report are presented in the Appendix.

Statistical analysis

The quantitive distribution of responses to questions on sleep-related symptoms and the subject's variables, such as age and BMI, was expressed by frequencies. The sample was divided by the Berlin Questionnaire score into two groups: the high-risk and the low-risk group. Comparisons of frequencies of responses between two groups, analysis of trend, calculation of the relative risks (RR), and sensitivity or specificity were made using the paired chi-square statistical test with Yates correction. Pregnant and postpartum women were included in the sample of this analysis, as the quotas were established by region. The level of statistical significance was 5% (p < 0.05). Computations were performed using SPSS 12.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Sample characteristics

The analysis sample of this report includes 1254 women; the demographic and anthropometric characteristics of the sample are listed in Table 1. Geographic distribution was consistent with the U.S. population, with 36% of the participants living in the South, 20% in the West, 26% in the Midwest, and 18% in the Northeast; 80.5% of women were Caucasian, and most reported that were married (70.5%), 11.7% were single, and 6.3% were living with someone. The majority were employed (64.1%), with 4.6% having more than one job, 43.2% working full-time, and 72% working a regular day shift.

Table 1.

Demographic and Anthropometric Characteristics of Participants in NSF Sleep in America 2007 Poll (n = 1254)

| Variable | % of responders |

|---|---|

| Sex | Female |

| Age, years | |

| 18–30 | 23.9 |

| 31–40 | 23.9 |

| 41–50 | 23.8 |

| 51–64 | 28.4 |

| White race | 80.5 |

| Married | 70.5 |

| Normal weight (BMI <25) | 40 |

| Overweight (BMI 25–30) | 36.4 |

| Obese (BMI >30) | 23.6 |

Prevalence of OSAS Symptoms

Classic OSAS symptoms

Snoring was reported commonly (51.5%) among the female population of the whole sample. Women at high risk for OSAS as estimated by the Berlin Questionnaire reported habitual snoring (61% vs. 19%, p < 0.01) and experienced apnea (7.2% vs. 0.6%, p < 0.001), daytime sleepiness (24% vs. 4.3%, p < 0.001), and drowsy driving (41% vs. 21.8 %, p < 0.001) more frequently than did women at low risk. Table 2 shows the prevalence of common OSAS symptoms in groups of women at low and high risk for sleep apnea.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Classic Symptoms of Sleep Disordered Breathing

| Symptom | Low risk (n = 936) | High risk (n = 318) |

|---|---|---|

| Snoring | 369 (39.4%) | 277 (87.1%) |

| Frequency | ||

| Every day/almost every day | 69 (19%) | 169 (61%) |

| A few days per week | 70 (19%) | 85 (30.7%) |

| A few days per month | 108 (29.2%) | 8 (2.9%) |

| Rarely | 81 (21.9%) | 8 (2.9%) |

| Refused/don't know | 41 (11.1%) | 7 (2.5%) |

| Loudness | ||

| Louder than breathing | 234 (63.4%) | 111 (40.1%) |

| As loud as talking | 66 (17.8%) | 85 (30.7%) |

| Louder than talking | 18 (4.9%) | 27 (9.7%) |

| Very loud | 20 (5.4%) | 41 (14.8%) |

| Refused/don't know | 31 (8.4%) | 13 (4.7%) |

| Witnessed stops of breathing | ||

| Every day/almost every day | 6 (0.6%) | 23 (7.2%) |

| A few days per week | 6 (0.6%) | 10 (3.1%) |

| A few days per month | 12 (1.3%) | 8 (2.5%) |

| Rarely | 54 (5.8%) | 41 (12.9%) |

| Never | 811 (86.6%) | 203 (63.8%) |

| Refused/don't know | 47 (5%) | 33 (10.3%) |

| Sleepiness | ||

| Every day/almost every day | 40 (4.3%) | 77 (24.2%) |

| A few days per week | 73 (7.8%) | 103 (32.4%) |

| A few days per month | 184 (19.6%) | 48 (15.1%) |

| Rarely | 351 (37.5%) | 47 (13.8%) |

| Never | 287 (30.6%) | 43 (13.5%) |

| Drowsy driving | ||

| >3 times per week | 22 (2.3%) | 28 (8.8%) |

| 1–2 times per week | 28 (2.9%) | 42 (13.2%) |

| 1–2 times per month | 156 (16.6%) | 60 (18.9%) |

| <1 time per month | 282 (30.1%) | 70 (22%) |

| Never | 428 (45.7%) | 105 (33%) |

| Do not drive | 20 (2.1%) | 11 (3.5%) |

| Car accident | 12 (1.3%) | 5 (1.6%) |

Insomnia

Among subjects with high risk for OSAS, the prevalence of insomnia symptoms was very high; 31.8% of high-risks responders on the Berlin Questionnaire reported difficulty in falling asleep almost every night in the past month in comparison to 15% (p < 0.05) of women at low risk. Of subjects at high risk of sleep apnea, 19% woke up too early and could not get back to sleep almost every night in comparison to 12% of women at low risk (p < 0.01). Also, 67% of women at risk for OSAS reported they were awake a great deal during the night.

Restless legs syndrome (RLS)

Symptoms of RLS, such as unpleasant feelings in the legs or an urge to move when lying down, reported to occur every night or a few nights a week were also more prevalent among subjects at high risk for OSAS than in women at low risk (33% vs. 13%, p < 0.01). Similarly, subjects at high risk had body movements and twitches more frequently than the rest of the sample (60% vs. 40%, p < 0.01).

Determinants of high risk for OSAS

The risk of OSAS was determined by responses to questions in the Poll that have been used in the Berlin Questionnaire. It was found that 25.4% (n = 318) of the female population in the United States are at a high risk for OSAS. Only 10% (31) of women at high risk for OSAS had been diagnosed with sleep apnea by their doctor.

Age

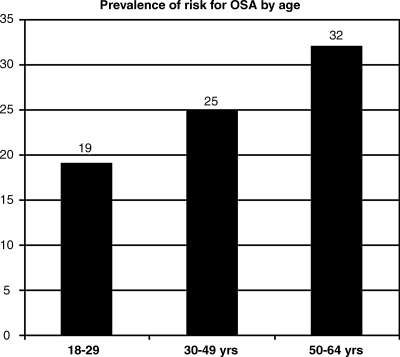

The risk for OSAS as determined by the Berlin Questionnaire score increased significantly with age (chi-square for trend = 5.6, p = 0.02). High risk for OSAS was found in 19% of women aged 18–29 years, 25% of those aged 30–49 years, and 32% of those aged 50–64 years (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

The prevalence of high risk for OSAS according to the Berlin Questionnaire among different age groups of women.

Weight

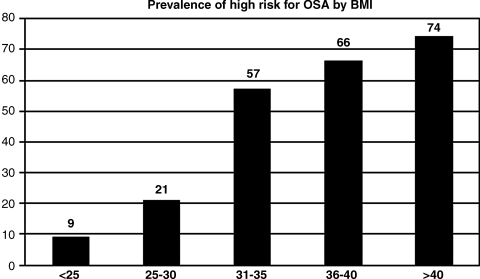

Risk for OSAS was increased significantly with obesity (chi-square for trend = 133, p < 0.001). Among those women with a normal BMI (BMI <25 kg/m2), 8.5% had a high risk score for OSAS and an RR of 0.27 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.20–0.36), whereas among overweight subjects (BMI 25–30 kg/m2), 21% had high risk score (RR = 0.77, CI 0.63-0.93). Among obese women (BMI > 30 kg/m2), 62% had a score compatible with risk for OSAS. The RR of a high score for OSAS increased with the BMI. Those with a BMI >30–35 had an RR of 3.91 (CI 2.96-5.16), those with a BMI >35–40 had an RR of 5.54 (CI 3.44-8.92), and those with a BMI >40 had an RR of 8.39 (CI 4.13-17.01) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

The prevalence of high risk for OSAS using the Berlin Questionnaire among different BMI groups in women.

Age and obesity

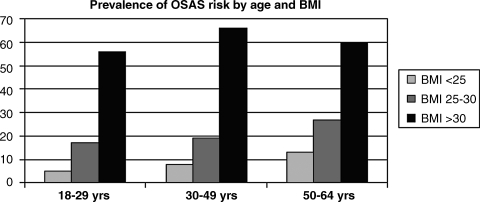

The prevalence of high risk for OSAS increased with higher BMI in all age groups (Fig. 3). The influence of obesity as defined by BMI >30 kg/m2 is more prominent in women <50 years old. The RR for a high score for OSAS risk in obese women aged 18–29 was 5.22 (CI 3. 24-8.39), in obese women aged 30–49 was 5.25 (CI 3.97-6.96), and in obese women aged 50–64 was 2.8 (CI 2.16-3.8). On the other hand, the influence of increased age (>50 years) was more prominent in normal weight women with an RR for a high Berlin score of 1.8 (CI 1.01-3.3) compared with 1.46 (CI 1.01-2.11) in overweight women. In obese women, the RR for increased age was 0.9.

FIG. 3.

The prevalence of high risk for OSAS according to the Berlin Questionnaire among different age groups with increasing BMI in women.

Reproductive status

The menstrual cycle status affects the risk for OSAS. Of women with regular cycles, 16% have high risk compared with 23% of those with irregular and unpredictable cycles and 33% of those who had not had a period in the last 12 months (chi-square for trend = 20.1, p < 0.001).

Menopause status influences the risk for OSAS; 35% of women who were postmenopausal were at high risk for OSAS compared with 21% of women who were perimenopausal and 23% of women who were not near menopause. The RR for OSAS among postmenopausal women was 1.6 (95% CI 1.31-2.01) in comparison to 0.78 (CI 0.52-1.61) for perimenopausal women and 0.86 for the rest of the women (CI 0.77-0.97).

Of pregnant women, 23% were found to have a high risk score on the Berlin Questionnaire. Risk for OSAS was also found to be associated with complications of pregnancy; 66% (6 of 9 pregnant women) who reported preeclampsia during pregnancy, 32% (6 of 19 women) with premature contractions, 25% (2 of 8) with gestational diabetes, and 33% (3 of 9) of those who reported preterm labor were among women at high risk for having OSAS.

Nineteen percent of postpartum women were found to be at high risk for OSAS; 31% of postpartum women reported loud snoring during pregnancy, with 11% of them snoring almost every night. Witnessed apneas or gasping were reported to occur every night or a few nights a week in 3.3% and 2.6% of postpartum women, respectively. Also, 21% of women with past pregnancies reported snoring during pregnancy, with 8% snoring almost every night. Observed apneas were reported to occur every night in 2.1% and a few nights a week in 3.1%. Among those who were snoring during pregnancy 45% reported that their snoring stopped after giving birth.

Comorbidities

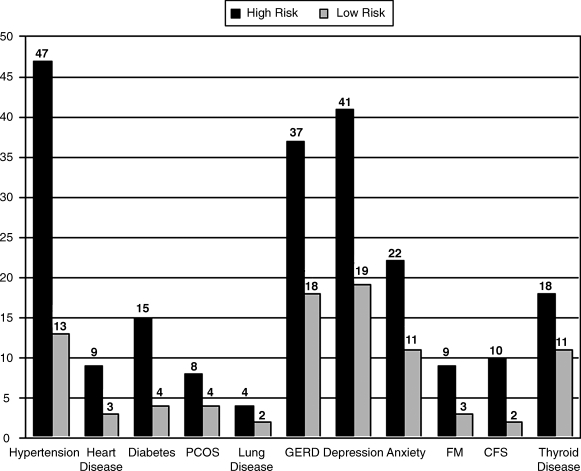

High risk for OSAS was associated with higher prevalence of chronic illnesses compared with low risk for OSAS. Heart disease, arterial hypertension, diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome, arthritis, and depression had higher prevalence among women who were at high risk for OSAS (Fig. 4) shows the relative associations.

FIG. 4.

The prevalence of medical comorbidities among women at high and low risk for OSAS.

Discussion

The most interesting finding of this analysis is that 1 in 4 women in the United States is at high risk for the presence of OSAS. Self-reported symptoms, such as habitual snoring, daytime sleepiness, and observed apnea, insomnia symptoms, and leg movements, are common in women at high risk for sleep apnea. The risk in women increases with advanced age, the presence of obesity, irregularity of the menstrual cycle, and menopause. Pregnant women had a similar risk for OSAS as nonpregnant women, and, more importantly in those pregnant women with high risk for OSAS, the reporting of pregnancy complications was very high. Women at high risk for OSAS have greater morbidity than women at low risk. Although many of our results also have been reported in previous studies, this analysis may help understand the lower prevalence of females in sleep medicine clinics, illustrating the possible atypical presentation of sleep apnea in women, and may help the medical community to increase its awareness about the significance of diagnosing sleep apnea in women. According to our results, OSAS prevalence in women may have increased in the United States in recent years. This report may enhance the need for future epidemiological studies.

Underrecognition of female cases of OSAS could be explained by a different clinical presentation.6 Several studies have investigated the gender-related differences in clinical presentation in order to explain the gender discrepancy in OSAS prevalence between general population and clinic-based studies. Redline et al.,7 in a general population study, reported that snoring and witnessed apnea were 2–3-fold more common in males. In contrast, data from the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study10 and the Sleep Heart Health study18 showed that women with sleep apnea report snoring, breathing cessation, and sleepiness equally with men. Clinical population studies11,19 also did not find significant gender-related differences in loud snoring and observed stops of breathing as symptoms at any level of apnea severity. Thus, data from both clinical and population-based studies suggest that the prevalence of common presenting symptoms of OSAS are not different between men and women and, therefore, cannot explain the reported lower prevalence of OSAS in the female population.

Our data showed that habitual snoring is common among women (19% of the whole sample). In a recent analysis from the 2005 NSF Sleep in America Poll,20 it was reported that habitual snoring was found in 13% of women and 19% of men. Thus, we found a higher prevalence among women that was equal to that reported previously among men. We also found that reported sleepiness at least a few days a week was also very common among females (23.3%).The 2005 NSF Poll analysis showed a similarly high prevalence of sleepiness in the general population (26%). Witnessed apneas every night were reported by 2.3% of women, similar to the prevalence reported in the 2005 Poll analysis (2% of women). Thus, the common symptoms of sleep apnea are also common in the female population and become significantly more prevalent among those women at high risk for sleep apnea. Witnessed apnea episodes, however, are less frequently reported than snoring among women at high risk. In clinical population studies,11,21 it has been shown that women with OSAS are less likely than men to report observed apneas, especially in milder forms of sleep apnea syndrome.19 This may be explained by a possibly different attitude of males to the sleep problems of their female bed partners. In conclusion, our data suggest that women at high risk for sleep apnea report symptoms of OSAS commonly and not differently from men, as has been shown in previous population studies.

It has been estimated that the prevalence of insomnia in the general population is about 10%,22 and female gender has been regarded as a risk factor for insomnia-like symptoms. About half of OSAS patients may have insomnia-like symptoms.23 We found that sleep onset insomnia, frequent awakenings, and maintenance insomnia were very common in the female population and that women at risk for the presence of sleep apnea had a higher prevalence of insomnia symptoms. Several studies have found that insomnia is much more likely to be the presenting symptom in women than in men. Although Krakow et al.24 found no gender difference in the frequency of insomnia symptoms in patients with sleep disordered breathing (SDB), Ambrogetti et al.21 showed that women had a 2-fold frequency of sleep onset insomnia compared with men. Shepertycky et al.11 showed that 1–5 women with OSAS had insomnia as the presenting symptom. In the community sample of the Sleep Heart Health Study,18 women more frequently than men had difficulty in falling or staying asleep, early morning awakenings, and leg cramps. Similarly, we found a strong association of unpleasant leg feelings and body movements with the estimated high risk for OSAS. These findings indicate that although women with OSAS frequently report the common symptoms, they may also have an atypical clinical presentation. Referring physicians should be aware of these features of clinical presentation in women and avoid relying only on the classic clinical symptoms. Atypical symptoms may explain the lower prevalence of female cases in clinic-based population studies. OSAS may not be different among genders, but there maybe some differences in particular aspects of presentation.

Risk factors for OSAS in women

We found that 1 in 4 women is at high risk for the presence of OSAS using the Berlin Questionnaire. This value is slightly higher than was found in the 2005 Poll for U.S. adults (21%) using similar methods,20 indicating a possible increase in the risk in women over these years. In our sample, 4% of women had been told by their doctors that they have OSA. This percentage, although not controlled with laboratory findings, is higher than the report from the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study1 reported in 1993, in which 2% of women met the minimal criteria for OSAS (AHI (apnea hypopnea index) >5 events per hour associated with daytime sleepiness). It is possible that OSAS is more prevalent in women today than it was previously. This could be attributed to the increase in obesity and age in the U.S. population or the increased diagnosis of female cases in sleep clinics.

OSAS is strongly associated with level of obesity.25 We found that high risk for OSAS was more prevalent among obese women and that the RR increased proportionally to obesity. Several population studies have demonstrated that the relationship of obesity to SDB is similar between men and women,15,26,27 although some have reported this relationship to be stronger in men than in women, who may develop SDB at much higher levels of obesity.28 Our findings showed a higher than 2-fold increase in high risk for OSAS in overweight subjects in comparison with normal weight women (8.5% vs. 21%, p < 0.01) and an almost linear relationship of obesity with high risk for OSAS, suggesting that obesity may be the major risk factor for OSAS in women.

The risk for significant SDB increases with age.25 It has been suggested that younger women are protected from developing sleep apnea by the action of the female hormones on upper airway function.29 Low levels of female sex hormones are associated with an increased probability for SDB in women who experience daytime sleepiness.30 Progesterone levels affect pharyngeal dilator muscle activity, and higher activity of the genioglossus has been observed during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.31 It has been reported that the majority of female OSAS patients are older than men and postmenopausal.32 In this report, we found that the risk for OSAS in women increases with age and that the RR for OSAS was almost 2-fold higher in postmenopausal women in comparison with perimenopausal women and those with normal menstrual cycle status. Menopause appears to be an important risk factor for OSAS.

Obesity seems to be more important than age in increasing the risk for OSAS, although in older women, its effect is smaller than in younger women. This finding may reflect the more important role of menopause in this age group (>50 years old). Younger women need to be more obese than older women in order to develop a high risk for OSAS.

Pregnancy may enhance the risk for sleep apnea by changes in the anatomy of the respiratory system, alterations in sleep architecture, and weight gain. On the other hand, increased levels of female hormones during pregnancy may protect women from developing SDB.33 Although it has been found that snoring increases during pregnancy,34 the true prevalence of OSAS in pregnancy is not known. We found that in pregnant women a similar proportion to that of the whole sample was at risk for OSAS. This indicates that the risk is not increased in pregnancy, perhaps because of protective mechanisms. Similarly, postpartum women and women with past pregnancies did not show greater prevalence of risk for OSAS in comparison to the whole sample of women. More interestingly, pregnant women who were found to be at risk for OSAS more frequently reported complications of pregnancy, such as preeclampsia, premature contractions, preterm labor, and gestational diabetes. This finding raises concerns about the role of SDB in adverse pregnancy outcomes. Although the true incidence of SDB-related preeclampsia remains to be determined, several reports have shown a relationship of snoring and SDB with this condition.35 Our findings support the hypothesis that although pregnant women may be protected from the development of SDB, existing SDB during pregnancy is associated with maternal complications.

Medical disorders and risk for OSAS in women

Women at high risk for SDB reported the occurrence of several medical disorders more frequently than did women at low risk. This has several clinical implications in the diagnosis and management of SDB. Several studies have shown that more women than men with OSAS have been diagnosed with depression in the initial presentation and that women are more likely to be treated for depression before the diagnosis of sleep apnea.11,36 This finding, along with the atypical symptoms observed in women, could partly explain the lower presentation of women in sleep clinics, as their physicians attribute their symptoms to other diagnoses.

Women with high risk for OSAS also more frequently reported arterial hypertension or heart disease than low-risk women, indicating a possible relationship of sleep apnea with increased cardiovascular morbidity.15 Women at risk reported a greater prevalence of diabetes and polycystic ovarian syndrome, a condition characterized by increased insulin resistance. Increased insulin resistance has been linked to the increased cardiovascular disease observed in SDB.37 However, higher morbidity rates among women at risk may be due to obesity rather than OSAS. The lack of comparison between groups matched for age and BMI does not allow us to exclude the confounding role of obesity.

Limitations of study

The major limitations of the study derive from its nature, as has been stated in the previous report of the NSF Poll.20 Data were collected from a telephone review and could be inaccurate. This could be more important in the calculation of BMI, as weight and height were self-reported. Ethnicity may play a significant role in the epidemiology of sleep apnea.25 Only 19% of participants described themselves as nonwhite, and this percentage is not representative of the U.S. population. Thus, the risk for sleep apnea may have been underestimated. It should be acknowledged that the Berlin Questionnaire determines high risk for OSAS depending on self-reported symptoms and obesity which are known predictors of OSAS. It would be more precise if symptoms were evaluated as predictors of SDB diagnosed by polysomnography. The use of a slightly different version of the Berlin Questionnaire may also have influenced the estimation of risk of OSAS. Finally, this analysis has a univariate nature when a multivariable analysis would better control for confounding factors.

Conclusions

We found that 1 in 4 women in the United States may be at risk for development of sleep apnea. OSAS is not rare in women, although they may have atypical clinical presentations that may mask the sleep apnea. Pregnancy does not seem to increase OSAS prevalence in women, but sleep apnea in pregnancy may lead to serious complications. The medical community should regard women and men equally for the possibility of having sleep apnea. The high morbidity reported for women at risk and the known relationship of OSAS to serious health consequences, especially in pregnancy, suggest that sleep clinics must expand recognition of female patients with OSAS.

Appendix: Berlin Questionnaire

The following questions were asked in the course of the telephone survey. Responses were recorded, and section sums were tallied. An individual was considered to have a high-risk Berlin score if two or more sections were positive.

Section 1

-

According to your own experiences or what others tell you, do you snore?

Yes (1)

No (0)

Don't know\refused (0)

-

Would you say that your snoring is … ?

Slightly louder than breathing (0)

As loud as talking (0)

Louder than talking (0)

Very loud and can be heard in adjacent rooms (1)

Don't know\refused (0)

-

How often do you snore?

Every night or almost every night ( 2)

A few nights a week (0)

A few nights a month (0)

Rarely\never (0)

Don't know\refused (0)

-

According to your own experiences or what others have told you, how often have you quit breathing during your sleep? Would you say … ?

Every night or almost every night ( 2)

A few nights a week (0)

A few nights a month (0)

Rarely\never (0)

-

Don't know\refused (0)

Add scores from questions 1 through 4.

If ≥2 check here _____

Section 2

-

How often do you have sleepiness during the day so badly that it interferes with your daily activities? Would you say … ?

Every day or almost every day ( 1)

A few days a week (1)

A few days a month (0)

Rarely\never (0)

Don't know\refused (0)

-

In the past year, have you had an accident or near accident because you dozed off or were too tired while driving?

Yes (1)

No (0)

Don't know\refused (0)

-

In the past year, how often have you driven a car or motor vehicle while feeling drowsy? Would you say you have driven drowsy … ?

3 or more times a week (1)

1 to 2 times a week (1)

1 to 2 times a month (0)

Rarely\never (0)

-

Don't know\refused (0)

Add scores from questions 1 through 3.

If ≥2 check here _____

Section 3

-

Do you have high blood pressure?

Yes (1)

No (0)

Don't know\refused (0)

What is your height?

What is your weight?

-

Body mass calculation (by the interviewer)

a. Is BMI >30 kg\m2?

i. Yes (1)

-

ii. No (0)

Add scores from questions 1 through 4.

If ≥1 check here _____

If ≥ two sections are checked, subject is at risk for sleep apnea.

Acknowledgments

M.K. is the recipient of National Institutes of Health grant ROI HL082672-01.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Young T. Palta M. Dempsey J. Scatrud J. Weber S. Badur S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Exar EN. Collop NA. The upper airway resistance syndrome. Chest. 1999;115:1127–1139. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.4.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Block AJ. Sleep apnea, hypopnea, and oxygen desaturation in normal subjects. A strong male predominance. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:513–517. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197903083001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guilleminault C. Eldridge FL. Tilkian A. Simmons FB. Dement WC. Sleep apnea syndrome due to upper airway obstruction. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:296–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guilleminault C. Quera-Salva MA. Partinen M. Jamieson A. Women and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1988;93:104–109. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kapsimalis F. Kryger M. Gender and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Part 1: Clinical features. Sleep. 2002;25:409–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redline S. Kump K. Tishler PV. Browner I. Ferrete V. Gender differences in sleep disordered breathing in a community-based sample. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:722–726. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.8118642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffstein V. Szalai P. Predictive value of clinical features in diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 1993;16:118–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bixler E. Vgontzas A. Lin HM, et al. Prevalence of sleep disordered breathing in women. Effect of gender. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:608–613. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.9911064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young T. Hulton R. Finn L. Salfan B. Palta M. The gender bias in sleep apnea diagnosis. Are women missed because they have different symptoms? Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2445–2451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shepertycky M. Banno K. Kryger M. Differences between men and women in the clinical presentation of patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 2005;28:309–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohensin V. Gender differences in the expression of sleep disordered breathing: the role of the upper airway. Chest. 2001;120:1442–1447. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.5.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trinder J. Kay A. Kleiman J. Dunai J. Gender differences in the airway resistance during sleep. J Appl Psysiol. 1997;83:1986–1997. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.6.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young T. Evans L. Finn L. Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20:705–706. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young T. Finn L. Peppard PE, et al. Sleep disordered breathing and mortality: Eighteen-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. Sleep. 2008;31:1071–1078. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Netzer NC. Stoohs RA. Netzer CM. Clark K. Strohl KP. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:485–491. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Netzer NC. Hoegel JJ. Loude D, et al. Prevalence of symptoms and risk of sleep apnea in primary care. Chest. 2003;124:1406–1414. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.4.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baldwin C. Kapur V. Holberg C. Rosen C. Nieto J. Associations between gender and measures of daytime sleepiness in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2004;27:305–311. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valipour A. Lothhaller H. Rauscher H. Zwick H. Burghuber OC. Lavie P. Gender-related differences in symptoms of patients with suspected breathing disorders in sleep. A clinical population study using the Sleep Disorders Questionnaire. Sleep. 2007;30:312–319. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiestand D. Britz P. Goldman M. Phillips B. Prevalence of symptoms and risk of sleep apnea in the US population. Results from the National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America 2005 Poll. Chest. 2006;130:780–786. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.3.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ambrogetti A. Olson LG. Saunders NA. Differences in the symptoms of men and women with obstructive sleep apnea. Aust NZ J Med. 1991;21:863–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1991.tb01408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roth T. Insomnia: Definition, prevalence, etiology and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(Suppl 5):S7–S10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavie P. Insomnia and sleep disordered breathing. Sleep Med. 2007;(Suppl 4):S21–S25. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krakow B. Melendrez D. Ferreira E, et al. Prevalence of insomnia symptoms in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Chest. 2001;120:1923–1929. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.6.1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young T. Peppard PE. Gottlieb J. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea. A population health perspective. State of the art. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1217–1239. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2109080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peppard PE. Young T. Plata M. Dempsey J. Skirted J. Longitudinal study of moderate weight change and sleep-disordered breathing. JAMA. 2000;284:3015–3021. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.23.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young T. Shahar E. Nieto FJ, et al. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:893–900. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.8.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newman A. Foster G. Livelier R. Nieto FJ. Redline S. Young T. Progression and regression of sleep disordered breathing with changes in weight. The Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2408–2413. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.20.2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Block AJ. Wynne JW. Boysen PG. Lindsey S. Martin C. Cantor B. Menopause, medroxyprogesterone and breathing during sleep. Am J Med. 1981;70:506–510. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90572-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Netzer NC. Elliason AH. Strohl KP. Women with sleep apnea have lower levels of sex hormones. Sleep Breath. 2003;7:25–29. doi: 10.1007/s11325-003-0025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Popovic RM. White DP. Upper airway muscle activity in normal women: Influence of hormonal status. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:1055–1062. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.3.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dancey RD. Hanly PJ. Soong C. Lee B. Hoffstein V. Impact of menopause on the prevalence and severity of sleep apnea. Chest. 2001;120:151–155. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pien GW. Schwab RJ. Sleep disorders in pregnancy. Sleep. 2004;27:1405–1417. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loube DI. Poceta JS. Morales MC. Peacock MD. Mitler MM. Self-reported snoring in pregnancy: Association with fetal outcome. Chest. 1996;109:885–889. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.4.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franklin KA. Holmgren PA. Jönsson F. Poromaa N. Stenlund H. Svanborg E. Snoring, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and growth retardation of the fetus. Chest. 2000;117:137–141. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith R. Ronald J. Delaive K. Wald R. Manfreda J. Kryger M. What are obstructive sleep apnea patients being treated for prior to this diagnosis? Chest. 2002;121:164–172. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vgontzas AN. Bixler EO. Chrousos GP. Sleep apnea as a manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9:211–224. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]