Abstract

Background

Neurocognitive functioning in schizophrenia has received considerable attention because of its robust prediction of functional outcome. Psychiatric symptoms, in particular negative symptoms, have also been shown to predict functional outcome, but have garnered much less attention. The high degree of intercorrelation among all of these variables leaves unclear whether neurocognition has a direct effect on functional outcome or whether that relationship to functional outcome is partially mediated by symptoms.

Methods

A meta-analysis of 73 published English language studies (total n = 6519) was conducted to determine the magnitude of the relationship between neurocognition and symptoms, and between symptoms and functional outcome. A model was tested in which symptoms mediate the relationship between neurocognition and functional outcome. Functional outcome involved measures of social relationships, school and work functioning, and laboratory assessments of social skill.

Results

Although negative symptoms were found to be significantly related to neurocognitive functioning (p < .01) positive symptoms were not (p = .97). The relationship was moderate for negative symptoms (r=−.24, n = 4757, 53 studies), but positive symptoms were not at all related to neurocogniton (r = .00, n= 1297, 25 studies). Negative symptoms were significantly correlated with functional outcome (r =−.42, p<.01), and again the correlation was higher than for positive symptoms (r = −.03, p = .55). Furthermore, our findings support a model in which negative symptoms significantly mediate the relationship between neurocognition and functional outcome (Sobel test p <.01).

Conclusions

Although neurocognition and negative symptoms are both predictors of functional outcome, negative symptoms might at least partially mediate the relationship between neurocognition and outcome.

Keywords: Meta-analysis, Schizophrenia, Neurocognition, Positive symptoms, Negative symptoms, Mediation model, Sobel test, Functional outcome

1. Introduction

Perhaps one of the most contemporary and compelling issues in schizophrenia research today is the understanding of the relative contribution of neurocognitive deficits and psychiatric symptoms to functional outcome. Neurocognitive deficits continue to be widely accepted as a core feature of the disorder (Green et al., 2004; Bellack et al., 2007; Harvey et al., 2006) because they are present not only in chronic patients when they are acutely ill, but also during periods of symptom remission. Similar deficits have also been found in first episode patients (Saykin et al., 1994; Albus et al., 1996; Bilder et al., 2000; Hoff and Kremen, 2003; Hoff et al., 2005). Several literature reviews that have included cross-sectional and longitudinal data demonstrate that neurocognitive functioning is a strong predictor of community functioning, such as social functioning, work performance, and social skills (Green, 1996; Green et al., 2000). In general, these studies conclude that neurocognitive functioning more robustly predicts functional outcome than do symptoms, especially positive symptoms (reality distortion). In contrast to the recent emphasis of the impact of neurocognitive deficits on functional outcomes in schizophrenia, psychiatric symptoms have received relatively less attention as predictors but are nonetheless significantly associated with community outcomes.

Several cross-sectional studies have suggested that performance on neurocognitive tests is correlated with at least one of the three of the major symptom factors, positive, negative, or disorganization (Roy and DeVriendt, 1994; Davidson and McGlashan, 1997; Rund et al., 1997; Addington and Addington, 1999, 2000; Brazo et al., 2002, 2005). Most of the studies seem to have found a stronger cross-sectional relationship with negative symptoms than with positive symptoms, non-disorganizing type (Harvey et al., 1998; Heaton et al., 1994; Corrigan and Toomey, 1995; Harvey et al., 2006; Keefe et al., 2006a,b). A substantial body of literature suggests that symptoms of disorganization, when reported as a separate factor, are also strongly related to neurocognition and warrant a separate empirical study. In particular, attentional deficits and poor performance in verbal fluency have been linked to severity of negative symptoms (Nuechterlein et al., 1986; Kerns et al., 1999; Howanitz et al., 2000). In addition, there is some evidence to suggest that negative symptoms or deficit syndrome patients have particular impairments in reasoning and problem solving (executive functioning) and on tests of motor functions as compared to memory functions (Cuesta et al., 1995; Berman et al., 1997; Zakzanis, 1998; Bryson et al., 2001; Bozikas et al., 2004); (Brazo et al., 2005). One study linked the severity of negative symptoms to IQ (Carlsson et al., 2006) while contradictory results of other studies show that this finding is not consistent (Simon et al., 2003; Brazo et al., 2002; Bozikas et al., 2004). Some have argued that schizophrenia patients with the greatest cognitive impairments have the most prominent negative symptoms (Brazo et al., 2005; Villalta-Gil et al., 2006). Thus, at least on a cross-sectional basis, neurocognition is linked to psychiatric symptoms (Harvey et al., 2006).

Although psychiatric symptoms have received relatively less emphasis recently as predictors of functioning, they are nonetheless significantly associated with community outcomes (Addington and Addington, 1999; Dickerson et al., 1999a,b; Norman et al., 1999; Addington and Addington, 2000; Suslow et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2002; Dickinson and Coursey, 2002; Malla et al., 2002; Hoffmann et al., 2003; McGurk et al., 2003; Lysaker and Davis, 2004; Milev, 2005; Pencer et al., 2005; Hofer et al., 2006; Bowie et al., 2006; Bozikas et al., 2006). Interestingly, positive (non-disorganizing) symptoms appear to interfere less with social and work functioning than do negative symptoms, yet both symptom groups appear to make independent contributions to community functioning (Pogue-Geile and Harrow, 1984; Breier et al., 1991; Herbener and Harrow, 2004). For instance, negative symptoms have predicted deficits in community functioning for up to two years following baseline assessments (Breier et al., 1991; Beng-Choon et al., 1998; McGlashan and Fenton, 1992; Herbener and Harrow, 2004). Despite the number of theorists who conclude that neurocognitive deficits should take center stage in predicting functional outcomes, there are compelling arguments and data suggesting that the importance of symptoms, in particular negative symptoms, should not be overlooked (Brekke et al., 2005; Harvey et al., 2006). The consistency of the cross-sectional association between negative symptoms and neurocognitive functioning, combined with the results of studies that examine symptoms as predictors of functional outcome, warrants further investigation of these complex relationships. This line of research raises the question of whether negative symptoms might mediate some of the associations observed between neurocognitive performance and functional outcome in schizophrenia.

This meta-analysis was conducted to determine if the relationship between neurocognitive functioning and functional outcome is mediated by the extent of positive (non-disorganizing) or negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. We hypothesized that the meta-analysis would support a mediation hypothesis for negative symptoms based on the strength of the relationship between neurocognition and negative symptoms, and negative symptoms and outcome.

2. Methods

2.1. Review procedures

A literature search was conducted in scientific journals covering the period from 1977 to December 31, 2006. The following databases were used in the literature search: PsychInfo, PsychAbstracts, EBSCOhost, PubMed, and Social Sciences Citation index. Searches were restricted to articles published in the English language. The following key search terms in schizophrenia were used (some terms were combined): neurocognition, neuropsychology, working memory, verbal learning and memory, executive functions, problem solving, attention/vigilance, symptoms, skills assessment, social functioning, work performance, and functional outcome. The reference lists of published articles were also searched to locate additional studies that were relevant. We cannot be certain that we were able to locate all of the published English language papers that met our inclusion criteria, but we were able to obtain a sufficiently representative number of relevant papers for empirical analysis.

Using these methods, over 200 articles were identified as potentially relevant to this topic. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) study must have used empirical methods and been published in a peer reviewed journal; (2) contained descriptions of study measures and operational definitions of variables; (3) used structured assessments of symptoms with established scales or standardized methods of symptom assessment; (4) neurocognitive functioning was assessed using standardized batteries; (5) all participants in the study must have been diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder according to DSM criteria (6) statistics reported must have been correlation coefficients or other statistics that could be converted into correlations (e.g. F-statistic, t-statistic) so that an effect size and z score could be calculated, and (7) sample data from a study were not included or published previously in another paper.

One hundred and eleven articles were eliminated due to not meeting these criteria. An additional 26 were excluded because the statistics they reported could not be converted into effect sizes or correlations for statistical analyses. A total of 73 studies met all the criteria (Table 1) which included 6519 patients. There were three primary categories of studies (see Table 1), those that examined (1) the relationship between neurocognition and symptoms, (2) the relationship between symptoms and functional outcome, and (3) interrelationships of all three. Studies of both inpatients and outpatients were included. If a study included cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses, we included only the cross-sectional data into our meta-analysis. We considered an interval between observations of less than 90 days to be cross-sectional. For each of the 73 studies a record was created that included (1) a description of the neuropsychological tests, e.g., Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT), (2) symptom measures, e.g., Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS), Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), (3) measures of functional outcome, e.g., QOL, (4) study statistics, e.g., correlation coefficients, and (5) study characteristics, such as gender ratio, patient status, diagnosis, location.

Table 1.

Studies included in meta-analysis, domains of interest, and number and type of subjects.

| Author(s) | Domains investigated | Number and type of subjects |

|---|---|---|

| Bell and Mishara (2006) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 267 outpatients |

| Bowie et al. (2006) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 78 outpatients |

| Bozikas et al. (2006) | Symptoms, outcome | 40 outpatients |

| Hofer et al. (2006) | Symptoms, outcome | 60 outpatients |

| Keefe et al. (2006a) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 1493 inpatients |

| Klingberg et al. (2006) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 135 outpatients |

| Moore et al. (2006) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 138 inpatients |

| Rocca et al. (2006) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 70 outpatients |

| Villalta-Gil et al. (2006) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 113 outpatients |

| Caligiuri et al. (2005) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 43 outpatients |

| Pencer et al. (2005) | Symptoms, outcome | 138 outpatients |

| Rhinewine et al. (2005) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 45 inpatients |

| Rocca et al. (2005) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 78 outpatients |

| Wegener et al. (2005) | Symptoms, outcome | 24 inpatients |

| Bowie et al. (2004) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 392 inpatients |

| Bozikas et al. (2004) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 58 outpatients |

| Evans et al. (2004) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 112 outpatients |

| Gooding and Tallent (2004) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 36 outpatients |

| Müller et al. (2004) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 100 inpatients |

| Pantelis et al. (2004) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 97 inpatients |

| Rund et al. (2004) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 207 outpatients |

| Addington et al. (2003) | Symptoms, outcome | 177 outpatients |

| Aghevli et al. (2003) | Symptoms, outcome | 33 outpatients |

| Hoffmann et al. (2003) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 53 inpatients |

| McGurk et al. (2003) | Symptoms, outcome | 30 outpatients |

| Minzenberg et al. (2003) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 57 outpatients |

| Simon et al. (2003) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 38 inpatients |

| Cameron et al. (2002) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 52 outpatients |

| Daban et al. (2002) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 51 inpatients |

| Friedman et al. (2002) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 124 inpatients |

| Malla et al. (2002) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 66 outpatients |

| Park et al. (2002) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 28 outpatients |

| Schuepbach et al. (2002) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 34 outpatients |

| Shean et al. (2002) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 92 outpatients |

| Smith et al. (2002) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 46 inpatients |

| Startup et al. (2002) | Symptoms, outcome | 64 inpatients |

| Guillem et al. (2001) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 27 outpatients |

| Moritz et al. (2001a) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 25 inpatients |

| Moritz et al. (2001b) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 47 inpatients |

| Silver and Shlomo (2001) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 36 outpatients |

| Addington and Addington (2000) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 65 outpatients |

| Howanitz et al. (2000) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 35 inpatients |

| McDaniel et al. (2000) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 37 inpatients |

| McGurk et al. (2000) | Symptoms, outcome | 168 inpatients |

| Stratta et al. (2000) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 20 inpatients |

| Addington and Addington (1999) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 80 outpatients |

| Dickerson et al. (1999b) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 72 outpatients |

| Kerns et al. (1999) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 26 inpatients |

| Norman et al. (1999) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 50 outpatients |

| Park et al. (1999) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 34 inpatients; 30 outpatients |

| Salem and Kring (1999) | Symptoms, outcome | 17 outpatients |

| Addington and Addington (1998a) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 40 inpatients |

| Addington and Addington (1998b) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 40 inpatients |

| Basso et al. (1998) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 53 outpatients; 9 inpatients |

| Harvey et al. (1998) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 97 outpatients |

| Robert et al. (1998) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 78 patients |

| Zakzanis (1998) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 38 inpatients |

| Addington et al. (1997) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 72 inpatients |

| Berman et al. (1997) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 30 inpatients |

| Brebion et al. (1997) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 40 inpatients |

| Salokangas (1997) | Symptoms, outcome | 227 outpatients |

| Carter et al. (1996) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 18 outpatients |

| Ragland et al. (1996) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 30 outpatients |

| Van der Does et al. (1996) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 60 inpatients |

| Brekke et al. (1995) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 40 inpatients |

| Cuesta and Peralta (1995) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 40 inpatients |

| Cuesta et al. (1995) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 30 inpatients |

| Hammer et al. (1995) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 65 outpatients |

| Franke et al. (1992) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 73 inpatients |

| Addington et al. (1991) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 38 inpatients |

| Breier et al. (1991) | Neurocognition, symptoms, outcome | 58 outpatients |

| Liddle and Morris (1991) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 43 inpatients |

| Green and Walker (1985) | Neurocognition, symptoms | 44 inpatients |

2.2. Defining neurocognition, positive and negative symptoms, and functional outcome

For the current study, neurocognition was operationally defined as cognitive processes that are measurable with structured neuropsychological tests, such as verbal learning and memory (Table 2). Selection of neurocognitive domains for analysis was guided by the MATRICS initiative (Nuechterlein et al., 2004). The current study included 6 of the 7 MATRICS domains of cognitive functioning: speed of processing, attention/vigilance, working memory, verbal learning visual learning, and reasoning and problem solving, but not social cognition. Because social cognition may itself be a mediator between neurocognition and functional outcome (Brekke et al., 2005; Sergi et al., 2006), we excluded it from this examination of symptom mediators between neurocognition and functional outcome.

Table 2.

Neurocognitive domains, symptom assessments, and functional outcome measures.

| Neurocognitive domain |

Neurocognitive test | Description of tests |

|---|---|---|

| Verbal learning and memory |

Logical Memory WMS-R | Subject is given two short stories and asked to recall each story immediately after presentation and again after a 30-minute delay. |

| Paired Associates WMS-R | Subject is given 5 trials of paired word presentations and asked to recall the list immediately after presentation and again after a 30-minute delay. |

|

| California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) |

Test consists of an oral presentation of a 16-word list (list A) for five immediate recall trials, followed by a single presentation and recall of a second 16-word ‘interference’ list (list B). Free- and category-cued recall of list A is elicited immediately after recall of list B and again 20 min later. A recognition trial is also run. |

|

| Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT) |

A list of words each belonging to one of several semantic categories is presented verbally for three trials and then after a delay that the subject must recall |

|

| Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RVLT) |

The subject is given a list of 15 items and asked to recall them immediately over five trials. Subsequently, the subject is presented with an interference list. The subject is also given a story paragraph that contains the 15 words from initial list. |

|

| Buschke-List Learning Test | Multiple-trial list-learning task. | |

| Visual learning and memory |

Rey-Osterreith Complex Figures Test (Rey-O) |

The subject is asked to copy the stimulus figure. After a 3-minute and a 30-minute delay, the subject is asked to draw the figure from memory. |

| Visual Reproduction WMS-R |

The subject is asked to look at five figures for 10 s each. After the presentation of each figure, the stimulus is removed and the subject is asked to “draw the design” from memory. After 25 min, the subject is asked to draw as many of the designs as they can remember. |

|

| Benton Visual Memory Test (BVMT) |

Test of visual perception and visual memory using the presentation of 10 visual stimuli. | |

| Hooper Visual Orientation Test |

Subject is required to identify common objects that have been cut into parts and arranged illogically. | |

| Working memory | Digit Span Forward (WAIS) | Subject is instructed to repeat a string of numbers that increase in length over the task. |

| Digit Span Backwards (WAIS) | Subject is instructed to repeat a string of numbers in the reverse order presented. | |

| Spatial Span WMS-R | Subject is instructed to point to a series of blocks in the same or reverse order that is presented by the Examiner. | |

| Letter-Number Sequencing (WAIS-III) |

Subject is given a series of numbers and letters which must be repeated in numerical and alphabetical order. | |

| Digit Span Distractibility Test—Neutral |

Subjects hear short strings of digits with and without distracters and are asked to recall the digits in correct order. | |

| Reasoning and problem solving |

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) |

The subject is asked to sort a series of cards to one of four key cards that vary in shape, color and number of shapes. Feedback is provided. After 10 consecutive correct sorts, the test rules shift without warning to a new sorting rule. |

| Block Design (WAIS) | The subject is given a set of blocks and asked to arrange the blocks according to the stimulus picture presented | |

| Gorham's Proverbs— Interpretation |

The subject is given 12 proverbs for which he or she must provide an interpretation. | |

| Raven's Progressive Matrices | For each test item, the subject is asked to identify the missing segment required to complete a larger pattern. | |

| Speed of processing | Trail Making Test A & B | Part A requires the subject to connect series of numbered circles arrayed randomly on a sheet of paper using a pencil. In PART B the array consists of both numbers and letters, and the subject must connect them in alternating order |

| Stroop Test (Color-Word) | The subject is given words representing colors that are printed in different color ink. The subject is instructed to read the ink color as quickly as possible and later while ignoring the printed word. |

|

| Finger Tapping Test | Test that requires that the subject tap as rapidly as possible with the index finger on a small lever, which is attached to a mechanical counter. |

|

| Canceling Test of Zazzo | The subject is required to cancel target letters among an array of non-target letters. | |

| Controlled Oral World Association Test |

A measure of verbal fluency requiring the ability to generate words beginning with specific letters (F, A, and S) for 1 min each. |

|

| Chicago Word Fluency Test | Subjects are asked to generate as many words as possible that begin with an “S,” then a “C.” This is a timed task. | |

| Jones-Gorman Design Fluency Test |

Requires production of novel (original) abstract designs under a time constraint. | |

| Digit Symbol –(WAIS) | The subject is provided with numbers along with corresponding symbols and is required to reproduce symbols that correspond with a number on a grid. |

|

| Lexical Decision Task | Subjects are presented, either visually or auditorily, with a mixture of words and pseudo words. Their task is to indicate, usually with a button-press, whether the presented stimulus is a word or not. |

|

| Hayling Sentence | The test consists of two sets of 15 sentences each having the last word missing. The examiner reads each | |

| Completion Test | sentence aloud and the participant has to complete the sentences. | |

| Purdue Pegboard | The subject is asked to place pegs into a pegboard. | |

| Attention/vigilance | Continuous Performance Test (CPT) |

Subjects are told that they will see a series of letters presented on a screen. They are told to click a button (or computer mouse) only when they see the “target” stimulus. |

| Span of Apprehension (SOA) | Arrays of 3 or 12 letters are presented for 71 ms on a screen along with distracters. Subjects are instructed to report if they see a T or an F among the array of letters. |

|

| Digit Span Distractibility Test—Interference |

Subjects hear short strings of digits with and without distracters and are asked to recall the digits in correct order. |

| Symptom assessment scale | Description of measure |

| Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) |

An 18-item rating scale designed to assess psychiatric symptoms, including positive and negative symptoms, based on a semi-structured interview. |

| Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) |

A 29-item semi-structured scale that assesses observed and self-reported negative symptoms such as restricted affect, asociality, and amotivation |

| Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) |

A 35-item semi-structured scale that assesses observed and self-reported positive symptoms including formal thought disorder. |

| Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) |

A 30-item semi-structured measure that assesses psychiatric symptoms in domains such as positive, negative, and general symptoms in psychiatric patients. |

| Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale (CPRS) |

A 67-item self-report measure scored from 0 (no pathology) to 3 (maximum pathology) that assesses psychiatric symptoms such as hallucinations, anxiety, and depression. |

| Functional outcome scale | Description of measure |

| Quality of Life Scale (QLS) | A measure that is based on a semi-structured interview designed to assess quality of life in various domains of living. |

| Social Functioning Scale (SFS) | A measure of social functioning relevant to the functioning and impairments of individuals with schizophrenia. |

| Multnomah Community Ability Scale (MCAS) |

A 17-item instrument that assesses the community functioning of adult psychiatric patients social competence; adjustment to living; behavioral problems, and interference with daily living. |

| Work Behavior Inventory (WBI) | A standardized work performance assessment instrument specifically designed for patients with severe mental illness, consisting of 36 items divided into five subscales. |

| Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) |

A scale rated 0 through 100 used to subjectively rate symptom severity, and social and occupational functioning of psychiatric patients. |

| Social Behavior Scale (SBS) | A scale that rates 21 behavior areas such as hygiene, initiating conversations, etc., designed for use with long-stay patient populations or for community settings |

| Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale |

Designed to evaluate cognitive, and behavioral dysfunctions; cognitive and neurocognitive subscales. |

| Global Assessment of Social Functioning (GAS) |

A scale rated 0–100 based on the lowest level of recent functioning as determined by rater. |

| Life Skills Profile (LSP) | A 39-item measure designed specifically to assess general levels of function and disability in adults. |

| Disability Assessment Schedule (DAS) |

An instrument for a clinician's assessment of difficulty maintaining personal care, performing occupational tasks, and social functioning. |

| Social Adaptive Functioning Scale (SAFE) |

A scale that measures social-interpersonal, instrumental, and life skills functioning, rated based on observation, caregiver contact, and interaction with the patient. |

| Levels of Functioning Scale (LOFS) | Measures the quantity and quality of social relationships, occupational activity, and time spent in a psychiatric hospital. |

| WHOL-QOL Brief | A 26-item survey measuring the quality of life for a wide variety of populations. |

| Specific level of function (SLFS) | A 46-item clinician rated scale that documents functional deficits across psychosocial functional domains and addressing specific areas of a patient's needs. |

| Skills-based assessment | Description of measure |

| Facial Recognition Task (FRT) | This test requires matching a target face with up to three pictures of the same person presented in a six-stimuli array of faces. |

| Facial Discrimination Task (FDT) | This test consists of standardized black-and-white photographs of Caucasian actors exhibiting happy, sad, angry, and neutral faces that are used to measure emotion recognition skills. |

| Assessment of Interpersonal Problem-Solving Skills (AIPSS) |

A role-played simulation test that measures an examinee's ability to describe an interpersonal problem, derive a solution to the problem, and to enact a solution. |

| UCSD Performance Skills Assessment (UPSA) |

Performance based assessment of functional capacity in areas needed for independent living. |

The construct of symptoms included positive and negative symptom dimensions as measured by structured instruments (Table 2). Positive symptoms consisted of hallucinations and delusions (reality distortion) which were considered conceptually different from symptoms of disorganization (Dibben et al., 2009; Nieuwenstein et al., 2001). For the current analysis, we considered only the relationship between reality distortion and neurocognition, and reality distortion and functional outcome. We excluded a separate consideration of the relationship between symptoms of disorganization and neurocognition because this topic warrants an independent investigation. Therefore, studies or analyses were excluded that had combined disorganization with positive symptoms (reality distortion), e.g., the PANSS positive symptom factor which includes delusions, hallucinations, and conceptual disorganization, the total score from the SAPS which combined reality distortion, bizarre behavior, and formal thought disorder. For the definition of negative symptoms, we considered only those scales which measured negative symptoms, e.g., SANS, or had negative symptom items that were clustered together or were created through factor analysis, e.g., PANSS negative symptom factor.

The construct of functional outcome was divided into community functioning, skills assessment, and functional capacity (Table 2). Community functioning included work or school performance, social functioning, independent living, and quality of life. Social skill was measured in the laboratory using structured measures, e.g., a role-play test such as the Assessment of Interpersonal Problem-Solving Skills (AIPSS), and functional capacity, e.g., the University of San Diego Performance-Based Skills Assessment. Social skills and functional capacity are considered intermediate variables rather than direct measures functional outcome.

2.3. Data analysis procedures

For the main analysis we combined all 6 domains of neurocognitive functioning and created one composite neurocognitive variable to represent neurocognition. There were a sufficient number of studies for analysis in each of the separate domains that examined the relationship between neurocognition and symptoms, and also between symptoms with functional outcome. The relationship between neurocognition and functional outcome (estimated r =.30) was based on the meta-analysis by Green et al. (2000). Correlation matrices were constructed based on aggregated estimates of neurocognition, positive and negative symptoms, and functional outcomes. These 3 by 3 correlation matrices were derived by first transforming the observed (published) correlations in each study using Fisher’s r-to-z transformation. Where indicated, multiple results were averaged from the same domain, e.g., several tests of working memory were combined into a single observation for that study. The correlation coefficients were then combined into a single estimate of the population correlation by averaging them weighted by sample size (Hedges and Olkin, 1984). Based on these combined correlation coefficients, the studies were then tested for homogeneity by calculating a Q-statistic. Every neurocognitive domain proved to be heterogeneous at the .05% level. Some of the studies that contained multiple measures of the same neurocognitive variables showed evidence that the measures were heterogeneous even within studies. However, there were not enough examples of each particular test from different studies to conduct a random effects model controlling for both study and within-study measurement effects. As heterogeneity of measures is a known problem in the field, and because of the fact that the question of the adequate multivariate alpha level of a multi-Z study is not yet solved (Hafdahl, 2007), the decision was made to continue the analysis using all studies in our sample. Although the significance of the reported p-values may be exaggerated, the data presented here can at least be considered a preliminary analysis of the relationship between the variables of interest. The estimated correlation coefficients were then combined into the 3 by 3 correlation matrices of interest using the multi-Z method, and these combined meta-analytic correlation matrices are the basis of the reported correlations and follow-up analyses.

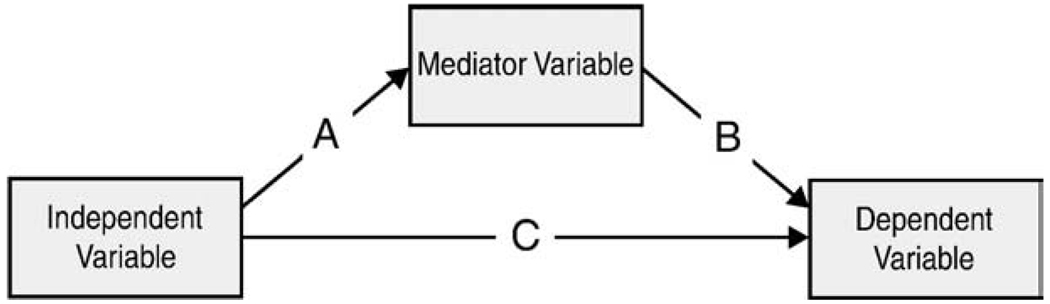

2.4. Testing mediation

For testing mediation, we followed the well-established procedures and conceptual understanding provided by Baron and Kenny (1986) (Fig. 1). The Sobel test (Preacher and Hayes, 2004) determines the significance of the indirect effect through the mediator by testing the hypothesis of no difference between the total effect (path c; neurocognition and functional outcome) and the indirect effect (path c′; neurocognition and symptoms, symptoms and outcome). The indirect effect of the mediator is the product of paths a and b; which is equivalent to (c–c′). As such a significant result of the Sobel test is evidence of partial mediation and does not make any claims about the absence or presence of complete mediation. The regression coefficients for the multiple regression predicting functional outcome from both neurocognitive variables and symptom ratings can be estimated from the pairwise correlation coefficients used to evaluate the strength of the indirect effect.

Deriving the estimate of the conditional correlations directly from the pairwise correlations makes it easier to account for different sample sizes underlying the different elements of the covariance matrix. This is done by calculating the standard error of the estimate of the regression coefficients based on the number of observations of a particular estimate. This approach is more straightforward than trying to determine the correct sample size of a structural equation model that has been fitted to data that are derived from a combined correlation matrix. Because of the lack of homogeneity of the neuropsychological tests (described above), three neurocognitive domains were chosen with the highest correlations for tests of indirect effects. These neurocognitive domains would most likely represent true effects in the population despite the fact that the significance of test statistics for these variables is potentially exaggerated. Even under conservative assumptions, such as assuming that the significance is 10 fold increased, a number of the results are still significant.

Fig. 1.

Typical mediation model.

3. Results

To provide a foundation for examining the variables of interest, we examined separately the relationship between neurocognition and symptoms, and the relationship between symptoms and functional outcomes. As the severity of illness might influence the functional relationship between these variables, we tested if these relationships differ between inpatient samples and out-patient samples. We considered the patient status as a proxy for severity of illness because we assume in-patient samples are in an acute phase of illness, while outpatients in general are stable. The results were identical for both types of patients in that negative symptoms were a significant mediator for both inpatients and outpatients. Therefore, all of the following results are presented for the combined sample which included both types of patients.

The cross-sectional relationship between neurocognition and positive symptoms (reality distortion) was not statistically significant (r=−.00, p = .97) as was the relationship between positive symptoms and community functioning (r =−.03, p = .55). Therefore, no test of mediation was performed (Table 3). In contrast, the effect size of the correlation between neurocognition and negative symptoms was moderate (r=−.24, p <.01) (Table 3). Negative symptoms were significantly related to functional outcome (r=−.42, p<.01) defined as community functioning and with skills assessment (r = −.28, p<.01)(Table 4). These significant relationships between neurocognition and negative symptoms, and between negative symptoms and functional outcome formed the basis for examining the mediation hypothesis.

Table 3.

The magnitude of relationships between neurocognition with symptoms, and symptoms with outcome is examined using average correlations across studies.

| Positive | Negative | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | n | Studies | r | p | n | Studies | |

| Neurocognitive domains | ||||||||

| Working memory | −.03 | = .54 | 357 | 8 | −.21 | <.01 | 2230 | 17 |

| Speed of processing | .04 | = .21 | 1040 | 18 | −.26 | <.01 | 3899 | 33 |

| Verbal learning and memory | .00 | = .93 | 531 | 10 | −.21 | <.01 | 2978 | 23 |

| Reasoning problem solving | .00 | = .94 | 797 | 16 | −.13 | <.01 | 3039 | 27 |

| Attention/vigilance | −.10 | = .15 | 199 | 4 | −.17 | <.01 | 2138 | 10 |

| Visual learning and memory | −.10 | = .20 | 179 | 4 | −.16 | <.01 | 454 | 8 |

| Composite of domains | .00 | = .97 | 1297 | 25 | −.24 | <.01 | 4929 | 53 |

| Outcome domains | ||||||||

| Community functioning | −.03 | = .55 | 549 | 9 | −.42 | <.01 | 2341 | 23 |

| Skills assessment | (no studies on this topic) | −.28 | <.01 | 269 | 5 | |||

Table 4.

The indirect effects of neurocognition on functioning mediated through negative symptoms were examined using a Sobel test of mediation.

| Neurocognition, symptom, and functioning variables examined |

Sobel | p |

|---|---|---|

| Speed of processing–negative symptoms–community functioning |

13.0 | <.01 |

| Verbal learning and memory–negative symptoms–community functioning |

9.9 | <.01 |

| Working memory–negative symptoms–community functioning |

8.5 | <.01 |

| Attention–negative symptoms–community functioning | 7.1 | <.01 |

| Reasoning and problem solving–negative symptoms– community functioning |

6.8 | <.01 |

| Visual learning and memory–negative symptoms–community functioning |

3.1 | <.01 |

|

Composite of domains–Negative symptoms–community functioning |

13.9 | <.01 |

| Speed of processing–negative symptoms–skill assessment | 10.1 | <.01 |

| Verbal learning and memory–negative symptoms–skill assessment |

8.2 | <.01 |

| Working memory–negative symptoms–skill assessment | 7.1 | <.01 |

| Reasoning and problem solving–negative symptoms–skill assessment |

6.3 | <.01 |

| Attention–negative symptoms–skill assessment | 6.3 | <.01 |

| Visual learning and memory–negative symptoms–skill assessment |

2.8 | <.01 |

| Composite of domains–Negative symptoms–skill assessment | 11.1 | <.01 |

Using the Sobel test for indirect effects, we examined the estimated strength of the indirect effect from independent variable to the dependent variable through the mediator, and the p-value to determine the level of significance (Table 4). We found support for the hypothesis that the relationship between neurocognition and community functioning and skills assessment was partially mediated by negative symptoms (Sobel test for indirect effects: z= 133.20, p<.01 and z = 4.33, p<.01, respectively). The relationship between neurocognitive domains and functional outcome (i.e., community functioning and skill assessment) was also partially mediated by negative symptoms (Table 4). As expected, and despite using the same methodology in calculating effect sizes, the estimated effect of negative symptoms on community functioning (estimated r=−.42) is much stronger than the estimated effect of positive symptoms (estimated r=−.03).

4. Discussion

We examined models that included neurocognition, positive symptoms, and negative symptoms as predictors of community-based functional outcomes and social skills in schizophrenia. Our meta-analyses showed there was strong cross-sectional evidence indicating that negative symptoms are related to community-based functional outcome and skill assessment. Using meta-analytic techniques, such as the Sobel test of mediation, yielded fairly strong evidence indicating that the relationship between neurocognition and functional outcome is at least partially mediated by negative symptoms. In this model, neurocognition is still a primary causal variable that influences outcome. However, we found that the total effects of neurocognition on outcome were at least partially mediated via an indirect path through negative symptoms. Therefore, neurocognition is proposed to have both direct and indirect effects on functional outcome.

Previous research has linked neurocognition to symptoms and symptoms to functional outcome, but in separate studies. In fact, there is a consistent and moderately strong relationship between neurocognition and negative symptoms. Harvey et al. (2006) suggested that cognitive deficits and negative symptoms share many features in common and are correlated, at least cross-sectionally. They point out that cognitive deficits and negative symptoms can have a similar type of onset, course, and are correlated with other aspects of schizophrenia, e.g., functional outcome. However, as far as we are aware, no prior meta-analysis has empirically tested a mediation model using the Sobel test to examine whether negative symptoms mediate between neurocognition and functional domains. The current results indicate that the relationship of negative symptoms to community-based functioning is relatively strong, but the relationship of positive symptoms to community-based functioning is relatively weak. Thus, positive symptoms (non-disorganizing type), such as hallucinations and delusions, do not consistently interfere with a person's ability to socialize or to perform at work. Patients might learn to compensate for positive symptom deficits in various ways, e.g., ignoring beliefs about aliens while working in retail clothing store. However, the data suggest that negative symptoms might be more closely linked to impairments in daily performance or skill acquisition. This relationship seems to hold for both inpatients and outpatients with schizophrenia.

Heterogeneity in the measurement of neurocognition was very evident in the studies included in this meta-analysis. Some neurocognitive tests were used very frequently, e.g., WCST. The constructs of executive functions, working memory, and attentional processes appeared to be oversampled as compared to constructs such as visual and spatial learning and memory. In addition, even within one domain of neurocognition, such as working memory, several tests were used, e.g., digit span measured auditory processing of working memory while spatial span tests measured visual working memory. In some cases, the same tests were classified in different studies as assessing different domains, probably because the tests demanded several different cognitive processes. For the current meta-analysis, we used the MATRICS classification scheme and definitions of domains (Nuechterlein et al., 2004) to place measures in domains based on the predominant cognitive process required.

There are several limitations to this study that warrant mention, some of which are common to all meta-analytic investigations (for a discussion, see: Rosenthal, 1991; Lipsey and Wilson, 2001). First, the study sample was not randomly selected. Additionally, neurocognition is not a homogenous concept and its measurement was influenced by how common a particular set of neurocognitive tests appear in the published literature. Therefore, the p-values that were averaged across studies are certainly not precise. The relationships in the studies in this meta-analysis are cross-sectional rather than longitudinal in design. For all of these reasons, and more, one cannot use meta-analysis or any correlational data, to infer causality. Further, the selection of which variables to place as predictors and which to test as a mediator was somewhat arbitrary. A theory driven approach was used to decide the direction that neurocognition is likely an underlying “causal” factor for the severity of negative symptoms. We do not believe that there is strong evidence suggesting that negative symptoms cause neurocognitive deficits. Similarly, the severity of symptoms most likely contributes to poor outcomes, but poor outcomes could conceivably contribute to a worsening of symptoms. In addition, we note the possibility of measurement overlap resulting in an inflated correlation between negative symptoms and outcome. With the SANS, there are definitions and anchor points for rating domains such as avolition at work or school that overlap with definitions of functional outcome. Despite the fact that each of these study limitations suggest that caution should be used in interpreting the results of the current study, our findings still provide some direction for future research on potential contributors to outcome. While we believe that this study can inform future outcomes research, we want to emphasize that a meta-analysis cannot replace focused empirical research.

The model of mediation that was tested in this study would benefit from further examination because it would, if validated through longitudinal observational and experimental designs, have implications for intervention. Considering the central role that neurocognitive deficits play in relationship to daily functioning in schizophrenia, it is not surprising that cognitive deficits have emerged as important targets for new treatments (Green and Nuechterlein, 1999; Carpenter and Gold, 2002; Carpenter, 2004; Gold, 2004). If the relationship between neurocognition and functional outcome is partially mediated by negative symptoms, then perhaps negative symptoms should be an additional treatment target as a means to improve functional outcome.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Lisa Guzik, B.A. for her contribution to the preparation of this manuscript

Footnotes

The findings from this meta-analysis were presented in part at the 10th bi-annual meeting of the International Congress on Schizophrenia Research, Colorado Springs, Colorado, March 28–April 1, 2007; Ventura, J., Hellemann, G.S., Thames, A.D, Koellner, V., and Nuechterlein, K.H. Negative Symptoms as a Mediator of the Relationship Between Neurocognition and Functional Outcome: A meta-analysis.

Role of funding source

There was no funding source.

Contributors

Joseph Ventura conceived the study design, data analysis plan, conducted literature searches, supervised the conduct of the study, and wrote the manuscript Dr. Hellemann conducted the data analysis and commented on all drafts of the manuscript. Ms. Thames performed literature searches, created tables, and commented on all drafts of the manuscript. Ms. Koeller conducted literature searches and organized study papers. Dr. Nuechterlein provided consultation of concepts we addressed and edited the final manuscript. All authors have contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has a financial conflict of interest.

References

- Addington J, Addington D. Facial affect recognition and information processing in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophrenia Research. 1998a;32(3):171–181. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Addington D. Visual attention and symptoms in schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up. Schizophrenia Research. 1998b;34(1–2):95–99. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Addington D. Neurocognitive and social functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1999;25(1):173–182. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Addington D. Neurocognitive and social functioning in schizophrenia: a 2.5 year follow-up study. Schizophrenia Research. 2000;44:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Addington D, Maticka-Tyndale E. Cognitive functioning and positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1991;5(2):123–134. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(91)90039-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Addington D, Gasbarre L. Distractibility and symptoms in schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 1997;22(3):180–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, van Mastrigt S, Addington D. Patterns of premorbid functioning in first-episode psychosis: initial presentation. Schizophrenia Research. 2003;62:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghevli MA, Blanchard JJ, Horan WP. The expression and experience of emotion in schizophrenia: a study of social interactions. Psychiatry Research. 2003;119(3):261–270. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albus M, Hubmann W, Wahlheim C, Sobizack N, Franz U, Mohr F. Contrasts in neuropsychological test profile between outpatients with first-episode schizophrenia. Acta Psychiutr Scand. 1996;94:87–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso MR, Nasrallah HA, Olson SC, Bornstein RA. Neuropsychological correlates of negative, disorganized and psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 1998;31(2–3):99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MD, Mishara AL. Does negative symptom change relate to neurocognitive change in schizophrenia? Implications for targeted treatments. Schizophrenia Research. 2006;81(1):17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellack AS, Green MF, Cook JA, et al. Assessment of community functioning in people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses: a white paper based on an NIMH-sponsored workshop. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33(3):805. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beng-Choon H, Nopoulos P, Flaum M, Arndt S, Andreasen NC. Two-year outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: predictive value of symptoms for quality of life. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1196–1201. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.9.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman I, Viegner B, Merson A, Allan E, Pappas D, Green AI. Differential relationships between positive and negative symptoms and neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 1997;25(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(96)00098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Robinson D, et al. Neuropsychology of first-episode schizophrenia: initial characterization and clinical correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:549–559. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Harvey PD, Moriarty PJ, Parrella M, White L, Davis KL. A comprehensive analysis of verbal fluency deficit in geriatric schizophrenia. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2004;19(2):289–303. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6177(03)00041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Reichenberg A, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Determinants of real-world functional performance in schizophrenia subjects: correlations with cognition, functional capacity, and symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):418. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozikas VP, Kosmidis MH, Anezoulaki D, Giannakou M, Karavatos A. Relationship of affect recognition with psychopathology and cognitive performance in schizophrenia. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2004 Jul;10(4):549–558. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704104074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozikas VP, Kosmidis MH, Kafantari A, Gamvrula K, Vasiliadou E, Petrikis P, Fokas K, Karavatos A. Community dysfunction in schizophrenia: rate-limiting factors. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2006;30(3):463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazo P, Marié RM, Halbecq L, et al. Cognitive patterns in subtypes of schizophrenia. European Psychiatry. 2002;17(3):155–162. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(02)00648-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazo P, Delamillieure P, Morello R, Halbecq L, Marié RM, Dollfus S. Impairments of executive/attentional functions in schizophrenia with primary and secondary negative symptoms. Psychiatry Research. 2005;133(1):45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brebion G, Smith MJ, Amador X, Malaspina D, Gorman JM. Clinical correlates of memory in schizophrenia: differential links between depression, positive and negative symptoms, and two types of memory impairment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154(11):1538–1543. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breier I, Schreiber JL, Dyer J, Pickar D. National Institute of Mental Health longitudinal study of chronic schizophrenia: prognosis and predictors of outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:239–246. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke JS, Raine A, Thomson C. Cognitive and psychophysiological correlates of positive, negative, and disorganized symptoms in the schizophrenia spectrum. Psychiatry Research. 1995;57:241–250. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02668-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke J, Kay DD, Lee KS, Green MF. Biosocial pathways to functional outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;80(2–3):213–225. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson G, Whelahan HA, Bell M. Memory and executive function impairments in deficit syndrome schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2001;102(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caligiuri MP, Hellige JB, Cherry BJ, Kwok W, Lulow LL, Lohr JB. Lateralized cognitive dysfunction and psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;80(2–3):151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AM, Oram J, Geffen GM, Kavanagh DJ, McGrath JJ, Geffen LB. Working memory correlates of three symptom clusters in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2002;110(1):49–61. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson R, Nyman H, Ganse G, Cullberg J. Neuropsychological functions predict 1 and 3-year outcome in first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatric Scandanavia. 2006;113:102–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter WT. Clinical constructs and therapeutic discovery. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;72(1):69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter WT, Gold JM. Another view of therapy for cognition in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51(12):969–971. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01399-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter C, Robertson L, Nordahl T, Chaderjian M, Kraft L, O'Shora-Celaya L. Spatial working memory deficits and their relationship to negative symptoms in unmedicated schizophrenia patients. Biological Psychiatry. 1996;40(9):930–932. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Toomey R. Interpersonal problem solving and information processing in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1995;21(3):395–403. doi: 10.1093/schbul/21.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta MJ, Peralta V. Cognitive disorders in the positive, negative, and disorganization syndromes of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 1995;58(3):227–235. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02712-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta MJ, Peralta V, Caro E, Leon J. Is poor insight in psychotic disorders associated with poor performance on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152(9):1380–1382. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.9.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daban C, Amado I, Bayle F, et al. Correlation between clinical syndromes and neuropsychological tasks in unmedicated patients with recent onset schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2002 Dec 15;113(1–2):83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, McGlashan TH. The varied outcomes of schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;42:34–43. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibben CR, Rice C, Laws K, McKenna PJ. Is executive impairment associated with schizophrenic syndromes? A meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2009 Mar;39(3):381–392. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson E, Boronow JJ, Ringel N, Parente E. Social functioning and neurocognitive deficits in outpatients with schizophrenia: a 2-year follow-up. Schizophrenia Research. 1999a;37(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson FB, Ringel N, Parente F. Predictors of residential independence among outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 1999b;50:515–519. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Coursey RD. Independence and overlap among neurocognitive correlates of community functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2002 Jul;56(1–2):161–170. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00229-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JD, Bond GR, Meyer PS, Kim HW, Lysaker PH, Gibson PJ, Tunis S. Cognitive and clinical predictors of success in vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;70(2–3):331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke P, Maier W, Hain C, Klingler T. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test: an indicator of vulnerability to schizophrenia? Schizophrenia Research. 1992;6(3):243–249. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(92)90007-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JI, Harvey PD, McGurk SR, et al. Correlates of change in functional status of institutionalized geriatric schizophrenic patients: focus on medical comorbidity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1388–1394. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JM. Cognitive deficits as treatment targets in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2004 Dec 15;72(1):21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooding DC, Tallent KA. Nonverbal working memory deficits in schizophrenia patients: evidence of a supramodal executive processing deficit. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;68(2–3):189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153(3):321–330. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Nuechterlein KH. Should schizophrenia be treated as a neurocognitive disorder? Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1999;25:309–318. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2000;26(1):119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Kern RS, Heaton RK. Longitudinal studies of cognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: implications for MATRICS. Schizophrenia Research. 2004 Dec 15;72(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillem F, Bicu M, Bloom D, Wolf MA, Desautels R, Lalinec M, Kraus D, Debruille JB. Neuropsychological impairments in the syndromes of schizophrenia: a comparison between different dimensional models. Brain and Cognition. 2001;46(1–2):153–159. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(01)80055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafdahl AR. Combining correlation matrices: simulation analysis of improved fixed-effects methods. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2007;32(2):180. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer MA, Katsanis J, Iacono WG. The relationship between negative symptoms and neuropsychological performance. Biological Psychiatry. 1995;37(11):828–830. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00040-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Howanitz E, Parrella M, White L, Davidson M, Mohs RC, Hoblyn J, Davis KL. Symptoms, cognitive functioning, and adaptive skills in geriatric patients with lifelong schizophrenia: a comparison across treatment sites. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1080–1086. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Green MF, Bowie C, Loebel A. The dimensions of clinical and cognitive change in schizophrenia: evidence for independence of improvements. Psychopharmacology. 2006;187(3):356–363. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton R, Paulsen JS, McAdams LA, Kuck J, Zisook S, Braff D, Harris MJ, Jeste DV. Neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenics: relationship to age, chronicity, and dementia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:469–476. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950060033003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV, Olkin I. Nonparametric estimators of effect size in metaanalysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;96(3):573–580. [Google Scholar]

- Herbener ES, Harrow M. Are negative symptoms associated with functioning deficits in both schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia patients? A 10-year longitudinal analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30(4):813. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer A, Rettenbacher MA, Widschwendter CG, Kemmler G, Hummer M, Fleischhacker WW. Correlates of subjective and functional outcomes in outpatient clinic attendees with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;256(4):246–255. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0633-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff AL, Kremen WS. Neuropsychology in schizophrenia: an update. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2003;16:149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff A, Svetina LC, Maurizio AM, Crow TJ, Spokes K. Familial cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2005;133(5B) doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann H, Kupper Z, Zbinden M, Hirsbrunner HP. Predicting vocational functioning and outcome in schizophrenia outpatients attending a vocational rehabilitation program. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2003;38(2):76–82. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0603-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howanitz E, Cicalese C, Harvey PD. Verbal fluency and psychiatric symptoms in geriatric schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2000;42(3):167–169. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RS, Bilder RM, Harvey PD, et al. Baseline neurocognitive deficits in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006a Apr 19; doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RS, Seidman LJ, Christensen BK, et al. Long-term neurocognitive effects of olanzapine or low-dose haloperidol in first-episode psychosis. Biological Psychiatry. 2006b Jan 15;59(2):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns JG, Berenbaum H, Barch DM, Banich MT, Stolar N. Word production in schizophrenia and its relationship to positive symptoms. Psychiatry Research. 1999;87(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingberg S, Wittorf A, Wiedemann G. Disorganization and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: independent symptom dimensions? European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;256(8):532–540. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0704-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle PF, Morris DL. Schizophrenic syndromes and frontal lobe performance. Br J Psychiatry. 1991 Mar;158:340–345. doi: 10.1192/bjp.158.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical Meta-analysis. Sage Pubns; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Davis LW. Social function in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: associations with personality, symptoms and neurocognition. Health Quality Life Outcomes. 2004;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malla AK, Norman RMG, Manchanda R, Townsend L. Symptoms, cognition, treatment adherence and functional outcome in first-episode psychosis. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:1109–1119. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel WF, Heindel CS, Harris DW. Verbal memory and negative symptoms of schizophrenia revisited. Schizophrenia Research. 2000;41(3):473–475. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH, Fenton WS. The positive–negative distinction in schizophrenia: review of natural history validators. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:63–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820010063008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk SR, Moriarty PJ, Harvey PD, Parrella M, White L, Davis KL. The longitudinal relationship of clinical symptoms, cognitive functioning, and adaptive life in geriatric schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2000;42(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Harvey PD, LaPuglia R, Marder J. Cognitive and symptom predictors of work outcomes for clients with schizophrenia in supported employment. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54(8):1129–1135. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.8.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milev P. Predictive values of neurocognition and negative symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal first-episode study with 7-year follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):495–506. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minzenberg M, Poole J, Vinogradov S, Shenaut G, Ober B. Slowed lexical access is uniquely associated with positive and disorganised symptoms in schizophrenia. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 2003;8(2):107–127. doi: 10.1080/135468000247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DJ, Savla GN, Woods SP, Jeste DV, Palmer BW. Verbal fluency impairments among middle-aged and older outpatients with schizophrenia are characterized by deficient switching. Schizophrenia Research. 2006;87(1–3):254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz S, Andresen B, Jacobsen D, Mersmann K, Wilke U, Lambert M, Naber D, Krausz M. Neuropsychological correlates of schizophrenic syndromes in patients treated with atypical neuroleptics. European Psychiatry. 2001a;16(6):354–361. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(01)00591-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz S, Heeren D, Andresen B, Krausz M. An analysis of the specificity and the syndromal correlates of verbal memory impairments in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2001b;101(1):23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(00)00241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller BW, Sartory G, Bender S. Neuropsychological deficits and concomitant clinical symptoms in schizophrenia. European Psychologist. 2004;9(2):96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenstein MR, Aleman A, de Haan EH. Relationship between symptom dimensions and neurocognitive functioning in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of WCST and CPT studies. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Continuous Performance Test. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2001 Mar–Apr;35(2):119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RMG, Malla AK, Cortese L, et al. Symptoms and cognition as predictors of community functioning: a prospective analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(3):400–405. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Edell WS, Norris M, Dawson ME. Attentional vulnerability indicators, thought disorder, and negative symptoms. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1986;12:408–426. doi: 10.1093/schbul/12.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2004 Dec 15;72(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Harvey CA, Plant G, et al. Relationship of behavioural and symptomatic syndromes in schizophrenia to spatial working memory and attentional set-shifting ability. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34(04):693–703. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Püschel J, Sauter BH, Rentsch M, Hell D. Spatial working memory deficits and clinical symptoms in schizophrenia: a 4-month follow-up study. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46(3):392–400. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00370-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Püschel J, Sauter BH, Rentsch M, Hell D. Spatial selective attention and inhibition in schizophrenia patients during acute psychosis and at 4-month follow-up. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51(6):498–506. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pencer A, Addington J, Addington D. Outcome of a first episode of psychosis in adolescence: a 2-year follow-up. Psychiatry Research. 2005;133(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogue-Geile ME, Harrow M. Negative and positive symptoms in schizophrenia and depression: a followup. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1984;10(3):371–387. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragland JD, Censits DM, Gur RC, Glahn DC, Gallacher F, Gur RE. Assessing declarative memory in schizophrenia using Wisconsin Card Sorting Test stimuli: the Paired Associate Recognition Test. Psychiatry Res. 1996 Mar 29;60(2–3):135–145. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(96)02811-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhinewine JP, Lencz T, Thaden EP, et al. Neurocognitive profile in adolescents with early-onset schizophrenia: clinical correlates. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;58(9):705–712. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert PH, Lafont V, Medecin I, Berthet L, Thauby S, Baudu C, Darcourt GUY. Clustering and switching strategies in verbal fluency tasks: comparison between schizophrenics and healthy adults. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 1998;4(06):539–546. doi: 10.1017/s1355617798466025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca P, Bellino S, Calvarese P, Marchiaro L, Patria L, Rasetti R, Bogetto F. Depressive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: different effects on clinical features. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2005;46(4):304–310. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca P, Castagna E, Marchiaro L, Rasetti R, Rivoira E, Bogetto E. Neuropsychological correlates of reality distortion in schizophrenic patients. Psychiatry Research. 2006;145(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic Procedures for Social Research. Sage Pubns; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Roy MA, DeVriendt X. Positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a current overview. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;39(7):407–414. doi: 10.1177/070674379403900704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rund BR, Melle I, Friis S, Larsen TK, Midbøe LJ, Opjordsmoen S, Simonsen E, Vaglum P, McGlashan T. Neurocognitive dysfunction in first-episode psychosis: correlates with symptoms, premorbid adjustment, and duration of untreated psychosis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004 Mar;61(3):466–472. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rund BR, Landro NI, Orbeck AL. Stability in cognitive dysfunctions in schizophrenic patients. Psychiatry Research. 1997;69:131–141. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(96)03043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem JE, Kring AM. Flat affect and social skills in schizophrenia: evidence for their independence. Psychiatry Research. 1999;87(2–3):159–167. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salokangas RK. Living situation, social network and outcome in schizophrenia: a five-year prospective follow-up study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1997;96(6):459–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saykin AJ, Shtasel DL, Gur RE, Kester DB, Mozley LH, Stafiniak P, Gur RC. Neuropsychological deficits in neuroleptic naive patients with first episode schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:124–131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950020048005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuepbach D, Keshavan MS, Kmiec JA, Sweeney JA. Negative symptom resolution and improvements in specific cognitive deficits after acute treatment in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2002;53(3):249–261. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergi MJ, Rassovsky Y, Nuechterlein KH, Green ME. Social perception as a mediator of the influence of early visual processing on functional status in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006 Mar;163(3):448–454. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver H, Shlomo N. Perception of facial emotions in chronic schizophrenia does not correlate with negative symptoms but correlates with cognitive and motor dysfunction. Schizophrenia Research. 2001;52(3):265–273. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon AE, Giacomini V, Ferrera E, Mohr S. Is executive function associated with symptom severity in schizophrenia? European Archives Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2003;253:216–218. doi: 10.1007/s00406-003-0421-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shean G, Burnett T, Eckman FS. Symptoms of schizophrenia and neurocognitive test performance. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58(7):723–731. doi: 10.1002/jclp.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TE, Hull JW, Huppert JD, Silverstein SM. Recovery from psychosis in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: symptoms and neurocognitive rate-limiters for the development of social behavior skills. Schizophrenia Research. 2002;55:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Startup M, Jackson MC, Bendix S. The concurrent validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;41(4):417–422. doi: 10.1348/014466502760387533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratta P, Daneluzzo E, Bustini M, Prosperini P, Rossi A. Processing of context information in schizophrenia: relation to clinical symptoms and WCST performance. Schizophrenia Research. 2000;44(1):57–67. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suslow T, Schonauer K, Ohrmann P, Eikelmann B, Reker T. Prediction of work performance by clinical symptoms and cognitive skills in schizophrenic outpatients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2000;188:116–118. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200002000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Does AJW, Dingemans P, Linszen DH, Nugter MA, Scholte WF. Symptoms, cognitive and social functioning in recent-onset schizophrenia: a longitudinal study. Schizophrenia Research. 1996;19(1):61–71. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(95)00046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalta-Gil V, Vilaplana M, Ochoa S, Haro JM, Dolz M, Usall J, Cervilla J. Neurocognitive performance and negative symptoms: are they equal in explaining disability in schizophrenia outpatients? Schizophrenia Research. 2006;87(1–3):246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener S, Redoblado-Hodge MA, Lucas S, Fitzgerald D, Harris A, Brennan J. Relative contributions of psychiatric symptoms and neuropsychological functioning to quality of life in first-episode psychosis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39(6):487–492. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakzanis KK. Neuropsychological correlates of positive vs. negative schizophrenic symptomatology. Schizophrenia Research. 1998;29(3):227–233. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(97)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]