Abstract

Behaviors beginning in childhood or adolescence may mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and involvement in prostitution. This paper examines five potential mediators: early sexual initiation, running away, juvenile crime, school problems, and early drug use. Using a prospective cohort design, abused and neglected children (ages 0–11) with cases processed during 1967–1971 were matched with non-abused, non-neglected children and followed into young adulthood. Data are from in-person interviews at approximate age 29 and arrest records through 1994. Structural Equation Modeling tested path models. Results indicated that victims of child abuse and neglect were at increased risk for all problem behaviors, except drug use. In the full model, only early sexual initiation remained significant as a mediator in the pathway from child abuse and neglect to prostitution. Findings were generally consistent for physical and sexual abuse and neglect. These findings suggest that interventions to reduce problem behaviors among maltreated children may also reduce their risk for prostitution later in life.

Keywords: child abuse, child neglect, prostitution, youth problem behavior

An extensive body of literature suggests that individuals involved in prostitution often come from abusive and neglectful childhood backgrounds (Bagley & Young, 1987; McClanahan, McClelland, Abram, & Teplin, 1999; Nixon, Tutty, Downe, Gorkoff, & Ursel, 2002; Potter, Martin, & Romans, 1999; Silbert & Pines, 1982; Simons & Whitbeck, 1991; Van Brunschot & Brannigan, 2002). However, the mechanisms that lead from childhood abuse and neglect to involvement in prostitution are not well understood (Cusick, 2006), largely because few studies have examined early behaviors that may mediate this relationship (Abramovich, 2005). Much of the early literature focused on psychological mechanisms that may link childhood sexual abuse to involvement in prostitution (e.g., James & Meyerding, 1977; Miller, 1986). Such conceptualizations, however, ignore risk associated with other forms of childhood abuse and neglect, as well as the range of social factors that are associated with engagement in prostitution. This paper expands upon previous work with a large prospective study that has documented a relationship between childhood abuse and neglect and involvement in prostitution in young adulthood (Widom & Ames, 1994; Widom & Kuhns, 1996; Wilson & Widom, in press) by using the same sample to examine youth problem behaviors (early sexual initiation, running away, juvenile crime, school problems, and drug use) as potential mediators of this relationship. Ecodevelopmental theory (Perrino, Gonzalez-Soldevilla, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2000; Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999) provides a theoretical framework for this investigation.

Ecodevelopmental theory integrates elements from social ecology (Bronfenbrenner, 1986), family systems (Henggeler & Borduin, 1990; Minuchin, 1974), and lifespan developmental theories (Baltes, Reese, & Nesselroad, 1977) and, as such, conceptualizes healthy and deviant development within the context of interacting processes including biology, family, peers, school, neighborhood, and the broader sociocultural environment. This theory has been used to describe risk for a number of adolescent problems, including sexual risk-taking (Perrino et al., 2000), drug use (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999), and antisocial behavior (Coatsworth, Pantin, McBride, Briones, Kurtines, & Szapocznik, 2000), and it is consistent with literature suggesting that involvement in prostitution results from a combination of developmental factors, such as abusive or neglectful parents, and situational factors, such as lack of employment or shelter (Dalla, 2000; McCaghy, 1985; McCarthy & Hagan, 1992; Silbert, Pines, & Lynch, 1982).

Ecodevelopmental theory views the family as the most proximal and powerful influence on the development of adaptive or maladaptive behavior patterns (Perrino et al., 2000) and suggests that family relationships impact other social contexts, such as peer groups and school, which further contribute to the development of deviant or healthy behavior (Perrino et al., 2000). From this perspective, childhood abuse and neglect may result in a cascading of negative effects across multiple domains of the developing child’s psychological and social functioning. For example, physiological changes in response to stress appear to have a global and adverse impact on neurological development, altering systems related to stress response, affect regulation, memory, social and emotional development, and cognition (De Bellis, 2001; Glaser, 2000). In turn, these neurological changes may impact academic success and social relationships and lead to involvement in deviant lifestyles at an early age. Failure in school, poor interpersonal skills and strained relationships, and/or involvement in risky activities such as crime and drug use may provide a context where trading sex is a normative, viable solution for meeting one’s needs. As Silbert and Pines (1982) concluded from their research with women involved in prostitution,

The primary picture emerging from both the quantitative and qualitative data of entrance into prostitution is one of juveniles running away from impossible situations at home, who are solicited for prostitution and start working for a pimp because they have no other means of support due to their young age, lack of education, and lack of the necessary street sense to survive alone. (pp. 488–489)

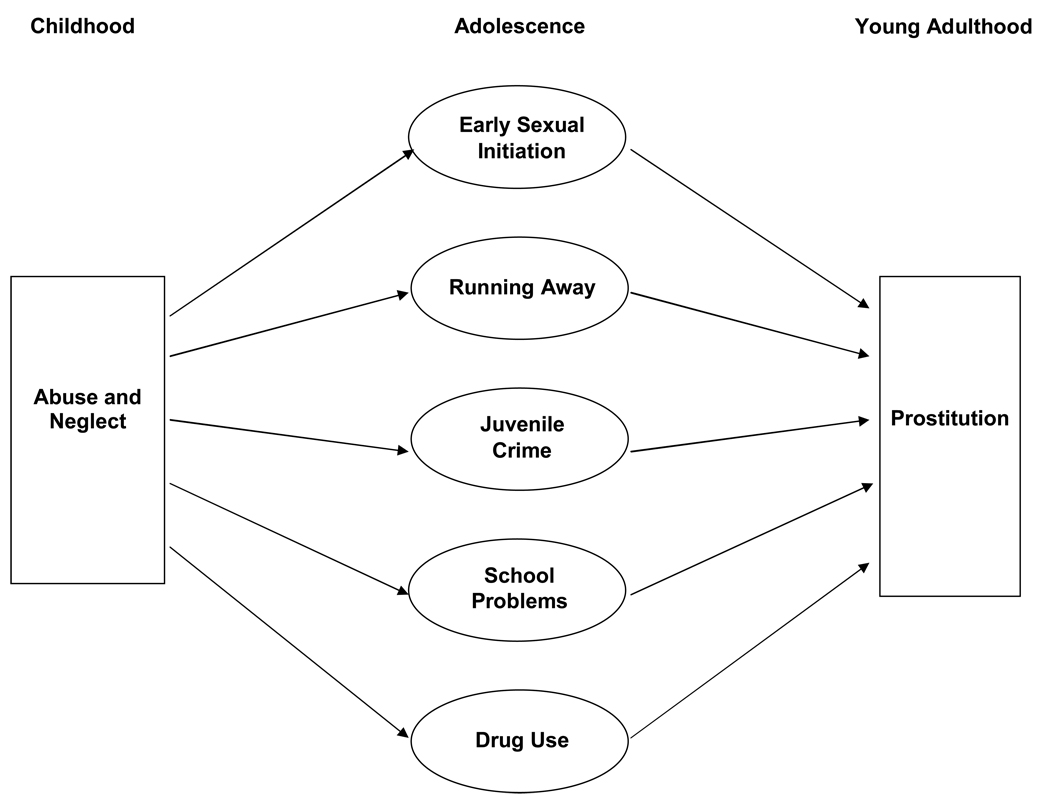

Consistent with ecodevelopmental theory, we expect that abusive and/or neglectful early family environments lead to problem behaviors in adolescence, which provide a facilitating context for involvement in prostitution by young adulthood. Ecodevelopmental theory suggests that evaluation of a single risk factor in isolation of related factors may over-estimate its effects (Perrino et al., 2000), and thus we evaluate a model including multiple pathways to involvement in prostitution. Specifically, we test a hypothetical model (see Figure 1) suggesting that five problem behaviors emerging in childhood and/or adolescence mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and involvement in prostitution: (1) early sexual initiation; (2) running away from home; (3) juvenile crime; (4) school problems; (5) and early drug use. Although we do not assess all of the ecological contexts that may contribute to risk for involvement in prostitution among victims of childhood abuse and neglect, the overarching theoretical framework for this work involves the assumption that risky family environments (e.g., child abuse and neglect) lead to a cascading of negative effects on other contexts (e.g., school, peer group) through disruptions of physiological and psychological processes. The mediating problems examined represent maladaptive behavior patterns resulting from these effects on multiple contexts of the child’s development. An extensive body of research suggests that these five youth behaviors are often associated with prostitution and with childhood abuse and neglect, but few attempts have been made to combine these literatures to build integrative developmental models describing mechanisms through which abused and neglected children may become involved in prostitution as they grow up. The literature review below describes empirical findings linking each of the five problem behaviors to involvement in prostitution or childhood abuse and neglect and discusses the ecological contexts of these linkages.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model linking childhood abuse and neglect to prostitution through five youth problem behaviors.

Potential Mechanisms Linking Childhood Maltreatment and Prostitution

Early Sexual Initiation

Studies have found that individuals who engage in prostitution tend to report earlier ages of sexual initiation than comparison groups (Potterat, Rothenberg, Muth, Darrow, & Phillips-Plummer, 1998; Van Brunschot & Brannigan, 2002), with the majority of individuals involved in prostitution reporting initiation of sexual activity before the age of 15 (Bagley & Young, 1987) and many by age 13 (Silbert & Pines, 1982; Van Brunschot & Brannigan, 2002). Likewise, victims of childhood maltreatment appear to initiate sexual activity at earlier ages than comparison groups (Lodico & DiClemente, 1994; Springs & Friedrich, 1992; Wilson & Widom, in press), and early sexual behavior may also be an indication of parental neglect (Van Brunschot & Brannigan, 2002). Prominent theories suggest that debased self-image (James & Meyerding, 1977) and emotional distancing from sex (Miller, 1986) among victims of sexual abuse may lead to early sexual behavior and subsequently to engagement in prostitution. A pattern of early sexual contact, including both abusive and consensual experiences, may also lead individuals to engage in prostitution by giving rise to a perception of sexual activity as a viable means for securing affection and intimacy as well as money, drugs, or other material objects (Dunlap, Golub, & Johnson, 2003). Less empirical or theoretical literature has addressed possible relationships between nonsexual forms of childhood maltreatment, early sexual behavior, and involvement in prostitution. However, nonsexual forms of childhood maltreatment may also lead to early and risky sexual behavior because of outcomes such as low self-esteem, desire for intimacy, and tendency to “act out” (Fiscella, Kitzman, Cole, Sidora, & Olds, 1998).

Running Away

A number of studies have reported a relationship between running away from home and involvement in prostitution or trading of sex for survival needs (Bagley & Young, 1987; Cusick, 2002; Halcon & Lifson, 2004; McCarthy & Hagan, 1992; Nadon, Koverola, & Schulderman, 1998; Tyler & Johnson, 2006; Van Brunschot & Brannigan, 2002). Runaway youths, lacking employment and financial resources, may resort to sex for money, drugs, shelter, or other “survival” purposes (Bagley & Young, 1987; McCarthy & Hagan, 1992; Tyler & Johnson, 2006). On the streets, moreover, the peer culture supports deviant activities such as trading sex (Chen, Tyler, Whitbeck, & Hoyt, 2004). Running away may be a response to an abusive or neglectful home environment for some youths (Abramovich, 2005; Bagley & Young, 1987; Rew, Fouladi, & Yockey, 2002; Rew, 2001; Silbert & Pines, 1982; Simons & Whitbeck, 1991), as evidenced by findings that victims of childhood abuse and neglect are more likely to run away from home than comparison groups (Kaufman & Widom, 1999; Yoder, Whitbeck, & Hoyt, 2001). In addition, several studies have found that runaway and homeless youths with histories of childhood abuse and neglect are more likely to engage in trading sex for money or other survival needs (Chen et al., 2004; McCarthy & Hagan, 1992; Tyler, Hoyt, & Whitbeck, 2000; Tyler & Johnson, 2006).

Juvenile Crime

Individuals may engage in prostitution as part of a generalized pattern of criminal behavior. Some conceptualizations of deviant juvenile behavior place sexual risk-taking as part of a broader syndrome of antisocial, destructive, and risky behaviors (Jessor, 1998), and prostitution is often associated with other criminal behavior (Cusick, 2002). For example, studies with youths living on the street have found correlations between trading sex and other criminal activities, such as theft and burglary (Chen et al., 2004; Simons & Whitbeck, 1991). Prospective evidence suggests that victims of childhood abuse and neglect are at risk for becoming involved in both juvenile and adult crime as they grow up (Widom, 1989a), and involvement in prostitution may occur as part of this broader syndrome of delinquent behavior (Widom & Kuhns, 1996).

School Problems

Individuals involved in prostitution report completing less education than comparison groups (Bagley & Young, 1987; Potter et al., 1999) and are more likely to have been expelled from school (Bagley & Young, 1987; Van Brunschot & Brannigan, 2002). In a study with women involved in street prostitution, the majority were not in school when they first became involved in prostitution despite being of school age, and 40% reported having problems when they were in school (Silbert & Pines, 1982). Low educational attainment puts individuals at a disadvantage in terms of getting jobs, and those with interrupted or incomplete education and history of school problems may be more likely to turn to prostitution out of financial desperation. Abused and neglected children are at risk for a variety of emotional, behavioral, and cognitive difficulties that interfere with their success at school (Veltman & Browne, 2001). Some research also supports an association between child maltreatment and school behavior problems such as truancy (Garnefski & Arends, 1998; Powers, Jaklitsch, & Eckenrode, 1989; Runtz & Briere, 1986).

Drug Use

Involvement in prostitution is often associated with drug use among adolescents and adults (Chen et al., 2004; Dalla, 2000; McClanahan et al., 1999; Potterat et al., 1998; Silbert & Pines, 1982). For example, one study found that women who engaged in prostitution were more likely than other women to report using and injecting drugs and beginning drug use before age 14 (Potterat et al., 1998). The direction of this association is not clear, however. Some research suggests that drug use precedes involvement in prostitution (McClanahan et al., 1999; Potterat et al., 1998; Silbert & Pines, 1982), and substance abusers may engage in prostitution to support their drug habit (Dalla, 2000; Dunlap et al., 2003). Other findings suggest that drug use begins or increases as a result of involvement in prostitution or survival sex (Chen et al., 2004; Cusick, 2002; Dalla, 2000; McClanahan et al., 1999; Silbert et al., 1982). Studies also report associations between childhood maltreatment and drug abuse in adolescence or adulthood (Brown & Anderson, 1991; Dembo, Williams, La Voie, Berry, Getreu, Kern, Genung, Schmeidler, Wish, & Mayo, 1990; Moran, Vuchinich, & Hall, 2004). Abused and neglected youths may initiate drug use as a way of coping with an aversive home environment (Harrison, Hoffmann, & Edwall, 1989b; Lindberg & Distad, 1985), to enhance self-esteem (Cavaiola & Schiff, 1989; Dembo, Williams, La Voie, Berry, Getreu, Wish, Schmeidler, & Washburn, 1989; Harrison et al., 1989b), to relieve symptoms of depression (Kazdin, Moser, Colbus, & Bell, 1985), or to obtain peer support (Singer, Petchers, & Hussey, 1989). Drug use may also develop as part of a general pattern of self-destructive behavior associated with low self-worth, poor self-concept, and self-blame (Lindberg & Distad, 1985). These traits, coupled with the motivation to support a drug habit, might make youths particularly vulnerable to involvement in prostitution.

The Present Study

Our primary hypothesis is that the five youth problem behaviors (early sexual initiation, running away, juvenile crime, school problems, and drug use) mediate the relationship between child abuse and neglect and involvement in prostitution (see Figure 1). We expect these relationships to be consistent for childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect.

Method

Overview

Data were collected as part of a large prospective cohort design study in which abused and neglected children were matched with non-abused, non-neglected children and followed into adulthood. Because of the matching procedure, the participants are assumed to differ only in the risk factor; that is, having experienced childhood sexual or physical abuse or neglect. Since it is not possible to assign subjects randomly to groups, the assumption of equivalency for the groups is an approximation. The control group may also differ from the abused and neglected individuals on other variables associated with abuse or neglect. For complete details of the study design and subject selection criteria, see Widom (1989a).

The initial phase of the study compared the abused and/or neglected children to the matched comparison group (total N = 1,575) on juvenile and adult criminal arrest records (Maxfield & Widom, 1996; Widom, 1989b). The second phase involved tracking, locating, and interviewing the abused and/or neglected and comparison groups during 1989 – 1995, approximately 20 years after incidents of abuse and neglect (N = 1,196). The interview consisted of a series of structured and semi-structured questionnaires and rating scales, including the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS-III-R), a standardized psychiatric assessment that yields Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III–R) diagnoses (Robins, Helzer, Cottler, & Goldring, 1989). The research presented in this paper draws on data collected during the follow-up interview and an updated criminal record review in 1994.

Participants and Design

The original sample of abused and neglected children (N = 908) was made up of substantiated cases of childhood physical and sexual abuse and neglect processed from 1967 to 1971 in the county juvenile (family) or adult criminal courts of a Midwestern metropolitan area. Cases of abuse and neglect were restricted to children 11 years of age or less at the time of the incident. A control group of children without documented histories of child abuse or neglect (N = 667) was matched with the abuse/neglect group on age, sex, race/ethnicity, and approximate family social class during the time that the abuse and neglect records were processed.

The control group represents a critical component of the study design. Children who were under school age at the time of the abuse and/or neglect were matched with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (± 1 week), and hospital of birth through the use of county birth record information. For children of school age, records of more than 100 elementary schools for the same time period were used to find matches with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (± 6 months), class in elementary school during the years 1967 to 1971, and home address, preferably within a five-block radius of the abused/neglected child. Overall, matches were found for 74% of the abused and neglected children. Non-matches occurred for a number of reasons. For birth records, non-matches occurred in situations when the abused and neglected child was born outside the county or state or when date of birth information was missing. For school records, non-matches occurred because of lack of adequate identifying information for the abused and neglected children or because the elementary school had closed and class registers were not available.

Of the original sample, 1,307 subjects (83%) were located and 1,196 (76%) participated in the first interview in 1989 – 1995. Of those not interviewed, 43 were deceased, 8 were unable to be interviewed, 268 were not found, and 60 refused to participate. The sample was an average of 29.2 years old (range = 19.0 – 40.7; S.D. = 3.8) and included 582 females (49%). Based on self reports of race/ethnicity, 61% of participants were White, non-Hispanic, 33% African American, 4% Hispanic, 1.5% American Indian, and less than 1% Pacific Islander or other. The sample was skewed toward the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum. The median occupational level (Hollingshead, 1975) for the group was semi-skilled workers, and only 13% held professional jobs. On average, participants completed 11.5 years of education (S.D. = 2.14), and 56.3% completed high school. Of the 1,196 participants, 520 were in the control group and 676 in the abuse and/or neglect group (543 cases of neglect, 110 cases of physical abuse, and 96 cases of sexual abuse). These numbers add up to more than 676 since some individuals experienced more than one type of abuse or neglect.

Procedures

Participants completed the interviews in their homes or, if preferred by the participant, another place appropriate for the interview. The interviewers were blind to the purpose of the study and to the inclusion of an abused and/or neglected group. Participants were also blind to the purpose of the study and were told that they had been selected to participate as part of a large group of individuals who grew up in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the procedures involved in this study, and subjects who participated gave written, informed consent. For individuals with limited reading ability, the consent form was presented and explained verbally.

Measures

Childhood Abuse and Neglect

Childhood physical and sexual abuse and neglect were assessed through review of official records processed during the years 1967 to 1971. Physical abuse cases included injuries such as bruises, welts, burns, abrasions, lacerations, wounds, cuts, bone and skull fractures, and other evidence of physical injury. Sexual abuse charges varied from relatively nonspecific charges of “assault and battery with intent to gratify sexual desires” to more specific charges of “fondling or touching in an obscene manner,” sodomy, incest, rape, etc. Neglect cases reflected a judgment that the parents’ deficiencies in child care were beyond those found acceptable by community and professional standards at the time and represented extreme failure to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, and medical attention to children.

Involvement in Prostitution

Involvement in prostitution was assessed with (1) official arrest records and/or (2) self reports of “ever having been paid for sex” on the DIS-III-R Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD) module. A single dichotomous variable (1 or 0) reflected involvement in prostitution.

Youth Problem Behaviors

Youth problem behavior variables -- early sexual initiation, running away, juvenile crime, school problems, and drug use -- are listed in Table 1 with descriptive statistics for the overall sample. Specific behaviors represented within each domain did not overlap (e.g., delinquent behaviors of running away and drug use were excluded from measures of juvenile crime).

Table 1.

Source and Descriptive Statistics of Youth Problem Behavior Variables

| Descriptives for overall sample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Variables | Source | Mean | S.D. | % | Range |

| Early sexual initiation | Sex before age 15 | Self report: DIS-III-R; CTS |

38.9 | 0 or 1 | ||

| Running away | Any arrest for running away | Official records | 4.7 | 0 or 1 | ||

| Running away before age 15 | Self report: DIS-III-R | 21.3 | 0 or 1 | |||

| Running away without returning home |

Self report: DIS-III-R | 1.4 | 0 or 1 | |||

| Number of times ran away before age 18 |

Self report: Wolfgang and Weiner (1989) | 1.42 | 3.49 | 0 – 20 | ||

| Juvenile crime | Number of juvenile arrests (non- status) |

Official records | .55 | 1.38 | 0 – 10 | |

| Arrested as a juvenile | Self report: DIS-III-R | 30.4 | 0 or 1 | |||

| Number of juvenile crimes committed by age 18 |

Self report: Wolfgang and Weiner (1989) | 1.85 | 2.70 | 0 – 16 | ||

| School problems | Any arrest for truancy | Official records | 1.7 | 0 or 1 | ||

| Misbehavior at school | Self report: DIS-III-R | 25.4 | 0 or 1 | |||

| Expulsions or suspensions | Self report: DIS-III-R | 45.2 | 0 or 1 | |||

| Frequent truancy | Self report: DIS-III-R | 35.0 | 0 or 1 | |||

| Drug Use | Drug use before age 15 | Self report: DIS-III-R | 23.5 | 0 or 1 | ||

| Number of drugs used as an adolescent |

Self report: DIS-III-R | 1.08 | 1.61 | 0 – 10 | ||

| Any drug-related juvenile arrest | Official records | 2.2 | 0 or 1 | |||

NOTE: Mean and standard deviation are reported for continuous variables, and percent prevalence is reported for dichotomous variables.

Early sexual initiation

Early sexual initiation was indicated by self-report of sex before age 15 in response to an item in the DIS-III-R APD module asking the age of first sexual relations and/or a subsequent interview question asking age of first sexual intercourse. A dichotomous variable was created to indicate the presence (1) or absence (0) of early sexual initiation. This variable refers only to whether the youth had these sexual experiences before age 15, not whether they were coercive or abusive or consensual with another youngster. Legally, of course, many of these sexual experiences would be considered abuse, even if they were consensual. It is also likely that some of these experiences reflect the sexual abuse that was documented in our sexual abuse cases.

Running away

Running away was represented by four observed variables (See Table 1): (1) self-report of having run away from home overnight before age 15 (0 or 1); (2) self report of running away without returning home (0 or 1); (3) self-report of the number of times a person ran away from home before age 18 (ranging from 0 to 20); and (4) officially recorded arrests for running away (0 or 1).

Juvenile crime

Juvenile crime was comprised of three observed variables: (1) number of officially documented juvenile arrests for non-status crimes (ranging from 0 to 10); (2) self-report on the DIS-III-R APD module of being arrested as a juvenile (0 or 1); and (3) number of crimes committed before age 18, self-reported on a measure adapted from Wolfgang and Weiner (1989). The number of crimes committed ranged from 0 to 16 and included such items as sexual and physical assault, carrying and/or using weapons, stealing, property damage, breaking and entering, auto theft, and disruption of neighborhood peace.

School problems

School problems were indicated by four observed variables: any officially documented arrest for truancy and self reports on DIS-III-R APD module of getting into trouble with a teacher or principal for misbehavior, being expelled or suspended, or frequent truancy (5 days or more in at least two school years) prior to the end of high school. Each variable in this domain was dichotomous (0 or 1).

Early drug use

Drug use was represented by three observed variables: (1) any official juvenile arrest for a drug-related offense; (2) self-report of use of any drugs before age 15 on the DIS-III-R drug use and abuse module (0 or 1); and (3) self-report on the DIS-III-R drug use and abuse module of the number of different drugs (marijuana, stimulants, sedatives, cocaine/crack, heroin, opiates, PCP, psychedelics, inhalants, other) used more than five times, beginning before age 18 (ranging from 0 to 10).

Statistical Analyses

Bivariate Relationships

Bivariate relationships between each of the mediating variables and both childhood abuse/neglect and involvement in prostitution were assessed, using logistic regression for dichotomous dependent variables and linear regression for continuous dependent variables. Logistic regression coefficients were converted to odds ratios (OR) through exponentiation; in the case of linear regression, standardized coefficients (β) were reported. Separate regressions assessed four criteria that are typically used to establish mediation (Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, 1998): (a) the predictor is related to the mediator; (b) the predictor is related to the outcome; (c) the mediator is related to the outcome, controlling for the predictor; and (d) the relationship between the predictor and the outcome is reduced when the mediator is included.

Structural Equation Model

Latent variable structural equation modeling (SEM) with Mplus 4 (Muthen & Muthen, 2006) was used to test a path model including all mediating variables (Figure 1) and controlling for race/ethnicity and gender. Only mediating variables supported by simple regressions were included in SEM analyses. The measurement model describing relationships between the observed mediating variables and latent constructs were first assessed. Then we assessed separate path models with each individual mediator, controlling for gender and race/ethnicity. Finally, we assessed the full structural path model for any abuse and/or neglect compared to controls and separately for each type of abuse or neglect. Race/ethnicity and gender were controlled by including paths from both variables to all youth problem behaviors and to prostitution.

Mplus 4 uses multivariate multiple regression to determine how well an entire model (measurement or structural) fits the data and provides multiple indices of overall model fit. A chi-square statistic (χ2) reflects the difference between the observed model relationships and estimated relationships based on the specified model; nonsignificant χ2 (p > .05) indicates a good fit. A Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) of .90 or higher indicate a good fit, and a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) of ≤ .05 is considered a close fit and < .08 adequate. Current recommendations support consideration of both the χ2 test and other indices of model fit (Barrett, 2007) since χ2 can be overly sensitive to discrepancies between observed and expected relationships with a large sample. Chi-square difference tests were used to assess alternate models with paths trimmed, with a significant χ2 indicating a significant reduction in model fit.

Individual factor loadings (measurement model) and path estimates (structural model) are reported in the form of standardized linear regression coefficients for continuous factor indicators or dependent variables, including latent constructs, and standardized probit regression coefficients for dichotomous dependent variables. Thus, the magnitudes of coefficients corresponding to continuous and dichotomous outcomes are not directly comparable. Probit coefficients represent change in the cumulative normal probability of the dependent variable associated with a one-unit increase in the predictor. Statistical significance was assessed with z-scores, and R2 provided a measure of effect size. Tests of indirect effects assessed the strength of mediated relationships. To handle missing data, we used full information maximum likelihood estimation, which uses all information available for each case and thus avoids biases and loss of power associated with traditional approaches to missing data (Allison, 2003; Curran & Hussong, 2003). Weighted least square parameter estimates were calculated using a diagonal weight matrix with standard errors and mean- and variance-adjusted χ2 test statistics that use a full weight matrix.

Results

Childhood Abuse and Neglect and Prostitution

Individuals with documented cases of child abuse and neglect were over twice as likely as controls to have engaged in prostitution (OR = 2.35, 95% CI = 1.54 – 3.58, p < .001). This relationship held for childhood physical abuse (OR = 2.45, 95% CI = 1.28 – 4.70, p < .01), sexual abuse (OR = 2.38, 95% CI = 1.20 – 4.72, p < .05), and neglect (OR = 2.45, 95% CI = 1.59 – 3.78, p < .001).

Childhood Abuse and Neglect and Youth Problem Behaviors

As shown in Table 2, individuals with documented histories of childhood abuse and neglect were at increased risk relative to controls for early sexual initiation, running away, juvenile crime, and school problems. For two low-frequency events, running away without returning home and arrests for truancy, there were zero cases in the control group. Thus, regression could not be conducted with these variables; however, cross-tabulations indicated significant group differences for both events (respectively, χ2 = 12.77, p< .001; χ2 = 14.64, p < .001). None of the drug-related outcomes was significantly associated with child abuse and neglect.

Table 2.

Relationships Between Youth Problem Behaviors and Childhood Abuse and Neglect and Prostitutions

| Predicting Youth Problem Behaviors | Predicting Prostitution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Controlling for Abuse/Neglect |

|||||||

| Abuse/Neglect | Control | OR (β) | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR a | 95% CI | |

| Early sexual initiation | 44.6 | 31.5 | 1.75*** | 1.37 – 2.22 | 4.37*** | 1.54 – 3.58 | 4.06*** | 2.69 – 6.13 |

| Running away | ||||||||

| Any arrest for running away | 6.5 | 2.3 | 2.95** | 1.54 – 5.64 | 3.17*** | 1.68 – 5.99 | 2.72*** | 1.43 – 5.19 |

| Running away (< age 15) | 28.3 | 12.1 | 2.87*** | 2.10 – 3.92 | 2.98*** | 2.01 – 4.42 | 2.60*** | 1.74 – 3.89 |

| Running away without returning home | 2.6 | 0 | NT | NT | 1.98 | .44 – 9.01 | 1.42 | .31 – 6.49 |

| Number of times ran away (< age 18) | 2.00 ± 4.27 | .67 ± 1.82 | (.19)*** | 1.13*** | 1.09 – 1.17 | 1.11*** | 1.07 – 1.54 | |

| Juvenile crime | ||||||||

| Self report of juvenile arrest | 36.3 | 22.7 | 1.94*** | 1.50 – 2.52 | 4.44*** | 3.00 – 6.57 | 4.09*** | 1.75 – 6.07 |

| Number of crimes committed (< age 18) | 1.97 ± 2.89 | 1.69 ± 2.42 | (.05)† | 1.21*** | 1.15 – 1.28 | 1.20*** | 1.14 – 1.27 | |

| Number of juvenile arrests | .70 ± 1.60 | .35 ± .98 | (.13)*** | 1.26*** | 1.14 – 1.39 | 1.22*** | 1.11 – 1.35 | |

| School problems | ||||||||

| Any arrest for truancy | 3.0 | 0 | NT | NT | 1.12 | .32 – 3.92 | 1.19 | .34 – 4.14 |

| Misbehavior at school | 29.5 | 20.0 | 1.68*** | 1.28 – 2.20 | 2.51*** | 1.71 – 3.69 | 2.32*** | 1.57 – 3.43 |

| Expulsions or suspensions | 48.8 | 40.5 | 1.40** | 1.11 – 1.76 | 3.82*** | 2.51 – 5.83 | 3.65*** | 2.39 – 5.58 |

| Frequent truancy | 39.4 | 29.2 | 1.58*** | 1.24 – 2.01 | 1.75** | 1.20 – 2.55 | 1.62* | 1.11 – 2.38 |

| Drug Use | ||||||||

| Drug use < age 15 | 25.3 | 21.2 | 1.25 | .95 – 1.65 | 3.44*** | 2.34 – 5.05 | 3.36*** | 2.28 – 4.95 |

| Number of drugs used (< age 18) | 1.12 ± 1.60 | 1.04 ± 1.57 | (.02) | 1.34*** | 1.22 – 1.46 | 1.34*** | 1.22 – 1.47 | |

| Any drug-related arrest (< age 18) | 2.8 | 1.3 | 2.12† | .88 – 5.08 | 4.09*** | 1.74 – 9.63 | 4.21*** | 1.74 – 10.17 |

NOTE: OR = odds ratio (dichotomous dependent variables); β = standardized linear regression coefficient (continuous dependent variables); CI = confidence interval; NT = Not tested because one group had zero cases. In first two columns, means and standard deviations are reported for continuous variables, and percentages are reported for dichotomous variables; statistical comparisons are between the childhood abuse and/or neglect group and the matched controls.

p < .10,

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

Youth Problem Behaviors and Prostitution

As seen in Table 2, nearly all youth problem behaviors were strongly associated with involvement in prostitution by young adulthood, in the expected positive direction. As the only exceptions, running away without returning home and arrests for truancy were not related to involvement in prostitution. Except for the number of drugs used by age 18, all associations with involvement in prostitution remained significant when abuse and neglect was controlled. Assessment of the four mediation criteria suggest that early sexual initiation, running away, juvenile crime, and school problems each partially mediate the relationship between childhood abuse and neglect and involvement in prostitution, since the direct relationship remained significant in individual regressions that included each of the problem behaviors.

Structural Equation Model

Measurement Model

Based on the results of regression analyses supporting partial mediation of the relationship between child abuse and neglect and prostitution, early sexual initiation, running away, juvenile crime, and school problems were included in SEM analyses. The drug use variables, running away without returning home, and arrests for truancy were dropped from SEM analyses. Thus, a four-factor model for the mediating variables were assessed, with latent variables for running away, juvenile crime, and school problems and a single observed indicator for early sexual initiation. For each latent variable, the loading of the highest-loading indicator was fixed at 1. The three latent variables were allowed to correlate with each other and with early sexual behavior.

The model yielded significant χ2 fit statistics, but χ2 is commonly high with large sample sizes. Other fit indices were acceptable (χ2 = 196.41, d.f. = 23, p < .001; CFI = .93, TLI = .93, RMSEA = .08), and all observed variables loaded strongly (p < .001) on their respective latent variables. The problem behaviors were all strongly correlated with each other (.59 for running away and juvenile crime, .54 for running away and school problems, .46 for running away and early sexual initiation, .78 for juvenile crime and school problems, .44 for juvenile crime and early sexual initiation, .45 for school problems and early sexual initiation). Therefore, a single factor comprised of all 10 observed variables was also assessed, but the single-factor model did not provide an acceptable fit based on any indices (χ2 = 454.26, d.f. = 27, p < .001; CFI = .84, TLI = .86, RMSEA = .12).

Structural Model

Before testing the full structural model, separate models were assessed for each mediating problem behavior, controlling for race/ethnicity and gender. As shown in Table 3, models with running away and school problems as mediators yielded acceptable overall fit indices. The CFI for the juvenile crime model indicated a good fit, but the TLI was higher and the RMSEA lower than acceptable fit criteria. The model for early sexual initiation was over-identified (i.e., all possible paths specified) and therefore overall fit indices could not be calculated.1 In all four models, paths to the respective problem behavior from abuse and neglect and from the problem behavior to prostitution were positive and significant. Indirect (i.e., mediational) effects of abuse and neglect through each problem behavior were statistically significant, but relatively modest.

Table 3.

Overall Fit Indices and Path Estimates for Structural Models for Each of 4 Adolescent Problem Behaviors

| Model Fit Indices | Path Estimates |

Indirect Effects |

Total Effects |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 (d.f.) sig. |

CFI | TLI | RMSEA | βa | β | β | ||

| Running away | 19.12 (7) | |||||||

| .01 | .99 | .97 | .04 | |||||

| Abuse/neglect to prostitution | .10† | .12*** | .22*** | |||||

| Abuse/neglect to running away | .30*** | |||||||

| Running away to prostitution | .38*** | |||||||

| Juvenile crime | 88.17 (8) | |||||||

| .00 | .91 | .84 | .09 | |||||

| Abuse/neglect to prostitution | .13** | .09*** | .22*** | |||||

| Abuse/neglect to juvenile crime | .19*** | |||||||

| Juvenile crime to prostitution | .44*** | |||||||

| School problems | 28.64 (8) | |||||||

| .00 | .96 | .93 | .05 | |||||

| Abuse/neglect to prostitution | .14** | .08*** | .21*** | |||||

| Abuse/neglect to school problems | .19*** | |||||||

| School problems to prostitution | .42*** | |||||||

| Early sexual initiation | .00 (0) b | |||||||

| .00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .00 | |||||

| Abuse/neglect to prostitution | .14** | .07*** | .22*** | |||||

| Abuse/neglect to early sexual initiation | .18*** | |||||||

| Early sexual initiation to prostitution | .41*** | |||||||

NOTE: χ2 = chi square statistic reflecting difference between specified model and observed model; d.f. = degrees of freedom; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation. Path estimates are direct effects.

β represents the standardized probit coefficient for dichotomous dependent variables (early sexual initiation, prostitution) and the standardized linear regression coefficient for continuous dependent variables (running away, juvenile crime, school problems).

Fit indices could not be calculated because the model is over-identified (i.e., includes all possible parameters).

p < .10,

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

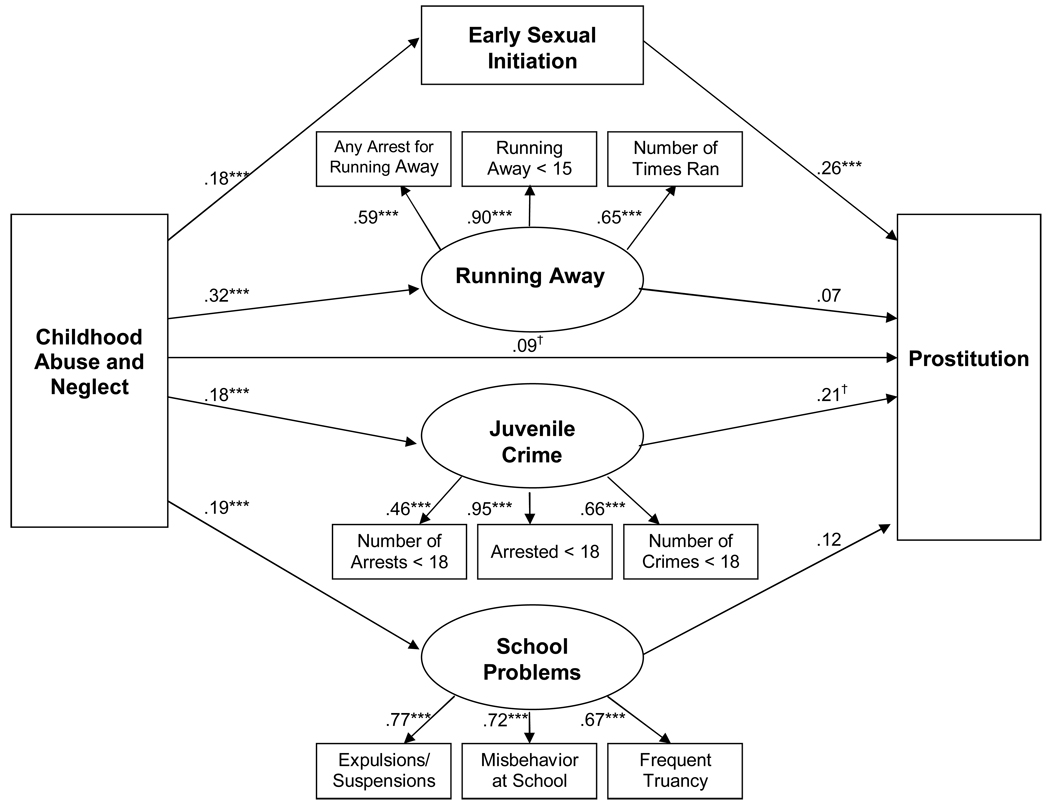

The full structural four-factor model included paths from abuse and neglect to early sexual initiation, to running away, to juvenile crime, and to school problems, from each of these behaviors to prostitution, and directly from abuse and neglect to prostitution. The mediating variables were allowed to correlate, and paths were included to control for race/ethnicity and gender. This model yielded fit indices within the acceptable range (χ2 = 310.92, d.f. = 43, p < .001; CFI = .91, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .07). R2s indicated that the model explained 33% of the variance in prostitution, 8% of the variance in early sexual initiation, 11% of the variance in running away, 21% of the variance in juvenile crime, and 16% of the variance in school problems. The full model with individual path estimates is depicted in Figure 2. Paths from abuse and neglect to early sexual initiation, running away, juvenile crime, and school problems were all significant and positive. Even when controlling for race/ethnicity and gender and the other youth problem behaviors, individuals with documented histories of abuse and/or neglect were at increased risk for each problem behavior. In predicting involvement in prostitution, however, only the path from early sexual initiation remained significant when all four problem behaviors were included. The path from juvenile crime to prostitution was marginally significant. The direct path from abuse and neglect to prostitution remained marginally significant in the full model, and its removal resulted in a marginally significant reduction of model fit (χ2 change = 2.89, d.f. = 1, p = .09). Total effects for this model were significant (β = .22, p < .0001). Total indirect effects were significant (β = .13, p < .0001), but the only significant indirect relationship was through early sexual initiation (β = .05, p < .01). Thus, early sexual initiation was the only youth behavior that mediated the relationship between child abuse and neglect and involvement in prostitution.

Figure 2.

Four-factor structural equation model linking childhood abuse and neglect to prostitution through youth problem behaviors. Numbers above the paths are standardized linear regression coefficients for continuous dependent variables and standardized probit regression coefficients for dichotomous variables. Gender and race/ethnicity are controlled.

*** p < .001 (2-tailed); † p < .10.

Models for Each Type of Childhood Abuse or Neglect

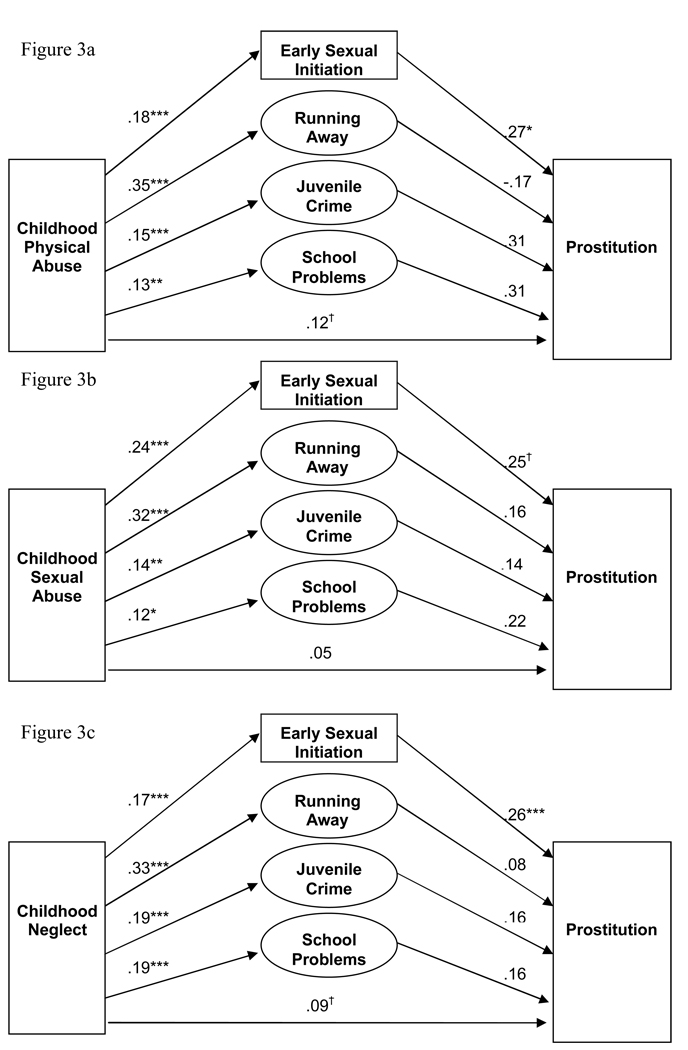

Physical abuse

Structural models for each type of childhood abuse and/or neglect are depicted in Figures 3a–c. The model for physical abuse yielded a slightly low TLI, but other fit indices were acceptable (χ2 = 185.57, d.f. = 36, p < .00; CFI = .90, TLI = .89, RMSEA = .08). This model explained 41% of the variance in prostitution, 9% of early sexual initiation, 13% of running away, 20% of juvenile crime, and 12% of school problems. As shown in Figure 3a, path estimates revealed a similar pattern as for abuse and neglect overall, with early sexual initiation as the only mediator that was significantly associated with involvement in prostitution. The direct path from physical abuse to prostitution was marginally significant and its removal from the model resulted in a marginally significant reduction in model fit (χ2 change = 2.81, d.f. = 1, p < .10). Total effects were significant (β = .20, p < .01), but neither direct (β = .12, p < .10) nor total indirect (β = .07, p < .10) reached significance on their own. Only the indirect effect through early sexual initiation was significant (β = .05, p < .05).

Figure 3.

a–c. Four-factor structural equation models linking specific types of childhood abuse and neglect to prostitution through youth problem behaviors. Figure 3a refers to physical abuse; Figure 3b refers to sexual abuse; and Figure 3c refers to neglect. Numbers above the paths are standardized linear regression coefficients for continuous dependent variables and standardized probit regression coefficients for dichotomous variables. Gender and race/ethnicity are controlled.

*** p < .001 (2-tailed); ** p< .01; * p < .05 † p < .10.

Sexual abuse

The model with sexual abuse yielded overall fit indices similar to the model with physical abuse (χ2 = 182.12, d.f. = 35, p < .001; CFI = .91, TLI = .89, RMSEA = .08) and explained 42% of the variance in prostitution, 12% of early sexual initiation, 10% of running away, 20% of juvenile crime, and 10% of school problems. As shown in Figure 3b, the path coefficients in this model reflected the pattern of results found for abuse and neglect overall. However, none of the mediators were significantly associated with prostitution; the path from early sexual initiation to prostitution remained the strongest of the set of mediators but was only marginally significant (β = .25, p < .10). The direct path from child sexual abuse to prostitution was not significant (β = .05, p > .10), and its removal did not impact model fit (χ2 change = .43, d.f. = 1, p > .10). The total indirect effects via the set of mediators were significant (β = .16, p < .001), but direct effects were not (β = .05, p > .10). The indirect effect through early sexual initiation was marginally significant (β = .06, p > .10). Here, it is important to note that the relatively small number of cases of sexual abuse (N = 96) reduced power to detect statistically significant effects in this model, which may be the reason that the relationship between early sexual initiation and prostitution did not reach significance.

Neglect

The model with neglect provided an adequate fit (χ2 = 264.54, d.f. = 43, p < .001; CFI = .92, TLI = .91, RMSEA = .07) and explained 35% of the variance in prostitution, 8% of early sexual initiation, 12% of running away, 20% of juvenile crime, and 15% of school problems. As shown in Figure 3c, the path estimates were consistent with findings for child abuse and neglect overall, revealing early sexual initiation as the strongest and only significant mediator in the full model (β = .26, p < .001). The direct path from child neglect to prostitution was marginally significant (β = .09, p < .10), and its removal marginally reduced model fit (χ2 change = 2.78, d.f. = 1, p < .10). Total indirect effects through the set of mediators were significant (β = .13, p < .001), and direct effects were marginally significant (β = .09, p < .10). The only significant effects for an individual mediator were through early sexual initiation (β = .05, p < .01).

Discussion

Findings from this study shed light on possible mechanisms linking childhood abuse and neglect to involvement in prostitution through youth problem behaviors. Victims of childhood abuse and neglect were at increased risk for multiple forms of youth problem behaviors -- early sexual initiation, running away, juvenile crime, and school problems -- compared to matched controls. Relative to other problem behaviors assessed here, initiation of sexual behavior before the age of 15 was the single strongest predictor of entry into prostitution.

These findings underscore the important role of early sexual initiation in leading to involvement in prostitution among abused and neglected children. These results support interventions to reduce sexual risk-taking and promote healthy sexual behavior among maltreated children as they grow up. It is important to note that at least some reports of early sexual initiation likely reflect instances of abuse, rather than voluntary sexual activity. In either case, however, it appears that early sexual contact among maltreated children indicates risk for later sexual risk-taking.

Importantly, findings from this study were generally consistent across the three types of child maltreatment assessed -- physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect. Most research has assessed childhood sexual abuse as a risk factor for early sexual initiation and prostitution. Our findings were stronger for victims of childhood physical abuse and neglect than sexual abuse. These results add to a growing body of literature revealing that outcomes for victims of childhood neglect are similar to (Maxfield & Widom, 1996; Widom, 1989b) or, in some cases, worse than (Bousha & Twentyman, 1984; Egeland, Sroufe, & Erickson, 1983) outcomes among victims of child abuse. Thus, victims of nonsexual forms of childhood maltreatment, as well as sexual abuse, would benefit from early evaluation and intervention to impede the development of early and health-compromising sexual behavior, such as engaging in prostitution.

Findings from this study suggest that romantic and sexual relationships may be the primary context leading to involvement in prostitution from childhood maltreatment. Disruption of early attachment relationships result in a maladaptive template for future relationships and unhealthy relationships with peers and romantic partners (Wolfe, Jaffe, & Crooks, 2006). Indeed, lack of positive family relationships can lead teenagers to early and unsafe sexual activity in their attempts to find emotional connection outside their families (Grotevant & Cooper, 1986; Whitbeck, Conger, & Kao, 1993). Romantic and sexual attractions can bring about strong emotions and considerable stress for teenagers (Collins, 2003; Furman & Shaffer, 2003; Welsh, Grello, & Harper, 2003) and often lead to intense fears of rejection and abandonment (Welsh et al., 2003). All adolescents have difficulty negotiating sexual situations (Carasso, 1998), but adolescents with histories of child abuse and neglect may be particularly vulnerable in such circumstances due to difficult family relationships and strong desires to maintain intimacy and avoid conflict with partners. At the same time, victims of child abuse and neglect are at increased risk for feelings of low self-efficacy, poor self-concept, and neurologically-based weaknesses in areas such as managing stress, processing emotions, and solving problems. Early sexual activity, whether consensual or coerced, may bring about and reinforce sexuality as a means of for securing relationships, receiving affection, and obtaining money or other objects (Browning & Laumann, 1997), thereby setting youths on a pathway of health-compromising sexual behavior.

Findings from this study lend support to the notion that youth problem behaviors, such as early sexual behavior, running away, juvenile crime, and school problems, overlap and co-occur for many youths (Huizinga, Loeber, & Thornberry, 1993; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Perrino et al., 2000). However, our results indicate that these behaviors also represent unique problems that should not be collapsed into one behavioral construct. The particular type of problem behavior engaged in, furthermore, may have important implications for outcomes later in life. In this study, early sexual initiation was the strongest risk factor for involvement in prostitution. Other youth behaviors may be associated with different outcomes. Furthermore, childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect each increased risk for several youth problem behaviors -- early sexual initiation, running away from home, juvenile crime, and school problems. Though early sexual behavior stood out as the most important risk factor for prostitution, all of these behaviors represent significant psychological and social problems, and our findings support interventions to reduce risk for these behaviors among victims of early maltreatment.

Results of this study do not indicate increased risk for youth substance use among victims of childhood abuse and neglect. There are number of reasons this research may have yielded different results than the extensive literature supporting a relationship between childhood maltreatment and substance use. On one hand, differences between this study design and most others (prospective versus cross-sectional, documented cases versus retrospective self-reports, and samples skewed toward the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum versus college student or middle class samples) make direct comparisons problematic. Although this paper represents the first examination of early onset drug use with this sample, other findings suggest that in this sample, risk for drug use problems associated with child abuse and neglect do not emerge until middle adulthood and exist primarily for women (Widom, Marmostein, & White, 2006). One interpretation of this finding is that high rates of substance use overall obscured differences between the abuse/neglect and control groups early in life, but that victims of abuse and neglect are less likely to than their peers to “mature out” of substance use as they age. Findings from this study do, however, suggest that early substance use indicates risk for prostitution. Previous findings with this sample suggest that substance use may represent a separate pathway to prostitution, independent of child abuse and neglect (Wilson & Widom, 2006).

Another possibility, however, is that the relationship between childhood maltreatment and substance abuse is more complex than the current analyses allowed. For example, abused and neglected youths may be at increased risk for using particular types of substances or for earlier use and more severe dependence. The marginally significant trend regarding juvenile arrests for substance-related offenses provides some suggestion that childhood abuse and neglect may increase risk for more serious drug problems resulting in contact with law enforcement, and we therefore encourage other researchers with large, prospective datasets to examine this relationship. Moreover, assessment of substance use during adolescence might provide a more sensitive measure of early drug use than our self-report measures, which are based on retrospective reports in young adulthood. While our results underscore the importance of targeting other problematic behaviors in working with maltreated youths, abused and neglected youth are a population in great need of intervention for a variety of risk behaviors, and their potential for substance use should not be ignored.2

This study provides several advantages. First, it employs a prospective matched cohort design, which provides an appropriate comparison group and determination of the correct temporal sequence of behaviors. Second, the sample is large and includes men and women, as opposed to the majority of studies in this area that focus exclusively on women (Abramovich, 2005). Third, assessment of involvement in prostitution is not limited to street prostitution and includes both self-reports and arrest records. Fourth, three different types of childhood maltreatment are examined -- physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect. Fifth, definitions of abuse and neglect are unambiguous. Sixth, we use documented cases of childhood maltreatment to minimize potential problems with reliance on retrospective self-reports. Seventh, we examine early behaviors that may predict involvement in prostitution and trace development beyond adolescence into young adulthood.

Despite its strengths, several limitations of this study must also be noted. First, although use of official records minimizes potential problems with reliance on retrospective self-reports, this strategy means that cases of abuse and neglect that did not come to the attention of authorities are not included. Second, our sample is skewed toward the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum, and therefore results cannot be generalized to cases of child abuse and neglect in middle class samples. Third, except for variables based on official records, youth problem behaviors were retrospectively reported by participants in young adulthood, and our model would be strengthened if replicated using data collected during childhood and adolescence.

Future research is needed to evaluate other potential mediators of the relationship between child abuse and neglect and involvement in prostitution that were not included in this analysis, such as self-efficacy or economic hardship. In addition, future research might examine outcomes of engagement in prostitution among victims of childhood abuse and neglect. Recent findings with the sample used in the present study suggested that engagement in prostitution increases risk for HIV in middle adulthood and provided some evidence that early sexual initiation and prostitution may mediate a link from childhood abuse and neglect to increased risk for HIV (Wilson & Widom, in press). Thus, a developmental pathway from childhood abuse and neglect, to risk behaviors in adolescence, and to prostitution by young adulthood may ultimately result in significant health problems such as HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases. It is also important that future research examine gender differences in the relationships reported in this paper since most research on engagement in prostitution has been with exclusively female samples, and therefore little is known about gender differences. We encourage other researchers with longitudinal data from younger cohorts of abused and neglected children to examine these issues.

In conclusion, results of this study contribute to our knowledge of the long-term effects of child maltreatment by providing prospective evidence that victims of childhood abuse and neglect are at increased risk for youth problem behaviors (early sexual initiation, running away, juvenile crime, and school problems) and that these behaviors partially mediate the pathway to involvement in prostitution by young adulthood. Our findings suggest that interventions to prevent problem behaviors, particularly early sexual initiation, among maltreated children may also reduce their risk for involvement in prostitution later in life. These findings add to a growing literature that indicates the need for public policy to support early intervention with children exposed to abuse and neglect, as well as other forms of trauma and violence. Rather than waiting until problems emerge, intervention before children become teenagers may help to reduce risk-taking behavior, thereby reducing risk for significant social and health problems, such as engagement in prostitution, later in life.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from NIMH (MH49467 and MH58386), NIJ (86-IJ-CX-0033, 89-IJ-CX-0007, and 93-IJ-CX-0031), NICHD (HD40774), NIDA (DA17842 and DA10060), NIAAA (AA09238 and AA11108), and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Points of view are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of the United States Department of Justice.

We also thank Sally Czaja for her consultation regarding statistical analyses.

Footnotes

This occurred because, unlike models with latent variables as mediators, the model with a single observed mediator did not have any degrees of freedom when all possible paths between variables were specified.

We appreciate and have incorporated in this discussion the thoughtful comments of a reviewer regarding early onset drug use in our sample.

References

- Abramovich E. Childhood sexual abuse as a risk factor for subsequent involvement in sex work: A review of empirical findings. In: Parsons JT, editor. Contemporary research on sex work. Hawthorne Press, Inc.; 2005. pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;117:545–557. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley C, Young L. Juvenile prostitution and child sexual abuse: A controlled study. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 1987;6:5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Reese HW, Nesselroad JR. Life-span developmental psychology: Introduction to research methods. Monterey, CA: Brooks-Cole; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett P. Structural equation modeling: Adjudging model fit. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:815–824. [Google Scholar]

- Bousha DM, Twentyman CT. Mother-child interactional style in abuse, neglect and control groups: Naturalistic observations in the home. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1984;93:106–114. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.93.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:723–742. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GR, Anderson B. Psychiatric morbidity in adult inpatients with childhood histories of sexual and physical abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:55–61. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning C, Laumann E. Sexual contact between children and adults: A life course perspective. American Sociological Review. 1997;62:540–560. [Google Scholar]

- Carasso MJ. Renegotiating HIV/AIDS prevention for adolescents. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 1998;21:203–216. doi: 10.1080/014608698265410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaiola A, Schiff M. Self-esteem in abused chemically dependent children. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1989;13:327–334. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(89)90072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Tyler KA, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Early sexual abuse, street adversity, and drug use among female homeless and runaway adolescents in the Midwest. Journal of Drug Issues. 2004;34:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, McBride C, Briones E, Kurtines W, Szapocznik J. Ecodevelopment correlates of behavior problems in young Hispanic females. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;6:126–143. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA. More than a myth: The developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Hussong AM. The use of latent trajectory models in psychopathology research. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:526–544. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusick L. Youth prostitution: A literature review. Child abuse review. 2002;11:230–251. [Google Scholar]

- Cusick L. Widening the harm reduction agenda: From drug use to sex work. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dalla RA. Exposing the "Pretty Woman" myth: A qualitative examination of the lives of female streetwalking prostitutes. The Journal of Sex Research. 2000;37:344–353. [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD. Developmental traumatology: The psychobiological development of maltreated children and its implications for research, treatment, and policy. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:539–564. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Williams L, La Voie L, Berry E, Getreu A, Kern J, Genung L, Schmeidler J, Wish ED, Mayo J. Physical abuse, sexual victimization and marijuana/hashish and cocaine use over time: A structural analysis among a cohort of high risk youths. Journal of Prison and Jail Health. 1990;9:13–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Williams L, La Voie L, Berry E, Getreu A, Wish E, Schmeidler J, Washburn M. Physical abuse, sexual victimization, and illicit drug use: Replication of a structural analysis among a new sample of high-risk youths. Violence and Victims. 1989;4:121–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E, Golub A, Johnson BD. Girls' sexual development in the inner city: From compelled childhood sexual contact to sex-for-things exchanged. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2003;12:73–96. doi: 10.1300/J070v12n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland BE, Sroufe LA, Erickson M. The developmental consequences of different patterns of maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1983;7:459–469. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(83)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Kitzman HJ, Cole RE, Sidora KJ, Olds D. Does child abuse predict adolescent pregnancy? Pediatrics. 1998;101:620–624. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.4.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Shaffer L. The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Arends E. Sexual abuse and adolescent maladjustment: Differences between male and female victims. Journal of Adolescence. 1998;21:99–107. doi: 10.1006/jado.1997.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser D. Child abuse and neglect and the brain-a review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2000;41:97–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, Cooper CR. Individuation in family relationships: A perspective on individual differences in development of identity and role-taking skill in adolescence. Human Development. 1986;29:82–100. [Google Scholar]

- Halcon LL, Lifson AR. Prevalence and predictors of sexual risks among homeless youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PA, Hoffmann NG, Edwall GE. Differential drug use patterns among sexually abused adolescent girls in treatment for chemical dependency. International Journal of the Addictions. 1989b;24:499–514. doi: 10.3109/10826088909081832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Borduin CM. Family therapy and beyond: A multisystemic approach to treating the behavior problems of children and adolescents. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks Cole Publishing; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four-factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Loeber R, Thornberry TP. Longitudinal study of delinquency, drug use, sexual activity, and pregnancy among children and youth in three cities. Public Health Reports. 1993;108:90–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James J, Meyerding J. Early sexual experience as a factor in prostitution. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1977;7:31–42. doi: 10.1007/BF01541896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. New perspectives on adolescent risk behavior. In: Jessor R, editor. New perspectives on adolescent risk behavior. Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor S. Problem behavior and psychosocial development -- A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman JG, Widom CS. Childhood victimization, running away, and delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1999;36:347–370. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin A, Moser J, Colbus D, Bell R. Depressive symptoms among physically abused and psychiatrically disturbed children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1985;94:298–307. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.94.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Bolger N. Data analysis in social psychology. In: Gilbert D, Fiske ST, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4th ed. Vol. 1. Boston: McGray Hill; 1998. pp. 233–265. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg FH, Distad LS. Survival responses to incest: Adolescents in crisis. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1985;9:521–526. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(85)90061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodico MA, DiClemente RJ. The association between childhood sexual abuse and prevalence of HIV-related risk behavior. Clinical Pediatrics. 1994;33:498–502. doi: 10.1177/000992289403300810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, Widom CS. The cycle of violence: Revisited six years later. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150:390–395. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaghy CH. Deviant behavior: Crime, conflict, and interest groups. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company; 1985. Prostitution; pp. 357–358. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy B, Hagan J. Mean streets: the theoretical significance of situational delinquency among homeless youths. The American Journal of Sociology. 1992;98:597–627. [Google Scholar]

- McClanahan SF, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Teplin LA. Pathways into prostitution among female jail detainees and their implications for mental health service. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:1606–1613. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.12.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EM. Street women. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin . Families and family therapy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Moran PB, Vuchinich S, Hall NK. Associations between types of maltreatment and substance use during adolescence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus (Version 4) 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Nadon SM, Koverola C, Schulderman EH. Antecedents to prostitution. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1998;13:206–221. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon K, Tutty L, Downe P, Gorkoff K, Ursel J. The everyday occurrence. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:1016–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Gonzalez-Soldevilla A, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. The role of families in adolescent HIV prevention: A review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3:81–96. doi: 10.1023/a:1009571518900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter K, Martin J, Romans S. Early developmental experiences of female sex workers: A competitive study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;33:935–940. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.1999.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potterat JJ, Rothenberg RB, Muth SQ, Darrow WW, Phillips-Plummer L. Pathways to prostitution: The chronology of sexual and drug abuse milestones. Journal of Sex Research. 1998;35:333–340. [Google Scholar]

- Powers JL, Jaklitsch B, Eckenrode J. Behavioral characteristics of maltreatment among runaway and homeless youth. Early Child Development and Care. 1989;42:127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Rew L, Fouladi RT, Yockey RD. Sexual health practices of homeless youth. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2002;34:139–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rew L, Taylor-Seehafer M, Thomas NY, Yockey RD. Correlates of resilience in homeless adolescents. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2001;33:33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Cottler L, Goldring E. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version III Revised (DIS-III-R) St. Louis, MO: Washington University; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Runtz M, Briere J. Adolescent acting out and childhood history of sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1986;1:326–334. [Google Scholar]

- Silbert MH, Pines AM. Entrance into prostitution. Youth & Society. 1982;13:471–500. [Google Scholar]

- Silbert MH, Pines AM, Lynch T. Substance abuse and prostitution. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1982;14:193–197. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1982.10471928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. Sexual abuse as a precursor to prostitution and victimization among adolescent and adult homeless women. Journal of Family Issues. 1991;12:361–379. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Petchers M, Hussey D. The relationship between sexual abuse and substance abuse among psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1989;13:319–325. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(89)90071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springs FE, Friedrich WN. Health risk behaviors and medical sequelae of childhood sexual abuse. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1992;67:527–532. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60458-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Coatsworth JD. An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model for risk and prevention. In: Glantz M, Hartel CR, editors. Drug abuse: Origins and interventions. Washington, DC: APA; 1999. pp. 331–366. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler K, Hoyt DR, Whitbeck LB. The effects of early sexual abuse on later sexual victimization among female homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15:235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Johnson KA. Trading sex: Voluntary or coerced? The experiences of homeless youth. The Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43:208–216. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brunschot EG, Brannigan A. Childhood maltreatment and subsequent conduct disorders: The case of female street prostitution. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2002;25:219–234. doi: 10.1016/s0160-2527(02)00103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veltman MWM, Browne KD. Three decades of child maltreatment research: Implications for the school years. Trauma, Violence and Abuse. 2001;2:215–239. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh DP, Grello CM, Harper MS. When love hurts: Depression and adolescent romantic relationships. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations: Theory, research, and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 185–212. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Conger RD, Kao M. The influence of parental support, depressed affect, and peers on the sexual behaviors of adolescent girls. Journal of Family Issues. 1993;14:261–278. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Child abuse, neglect and adult behavior: Research design and findings on criminality, violence, and child abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1989a;59:355–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. The cycle of violence. Science. 1989b;244:160–166. doi: 10.1126/science.2704995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Ames MA. Criminal consequences of childhood sexual victimization. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1994;18:303–318. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Kuhns JB. Childhood victimization and subsequent risk for promiscuity, prostitution, and teenage pregnancy: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:1607–1612. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Marmostein NR, White HR. Childhood victimization and illicit drug use in middle adulthood. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:394–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson H, Widom CS. An examination of risky sexual behavior and HIV among victims of child abuse and neglect: A thirty-year follow-up. Health Psychology. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.149. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, Widom CS. Substance abuse and prostitution among victims of child maltreatment: Pathway to HIV?; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Criminology; Los Angeles, CA. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Jaffe PG, Crooks CV. Adolescent risk behaviors: Why teens experiment and strategies to keep them safe. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgang ME, Weiner N. Unpublished interview protocol: University of Pennsylvania Greater Philadelphia Area Study. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder KA, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Event history analysis of antecedents to running away from home and being on the street. American Behavioral Scientist. 2001;45:51–65. [Google Scholar]