Abstract

Across numerous model systems, aging skeletal muscle demonstrates an impaired regenerative response when exposed to the same stimulus as young muscle. To better understand the impact of aging in a human model, we compared changes to the skeletal muscle transcriptome induced by unaccustomed high-intensity resistance loading (RL) sufficient to cause moderate muscle damage in young (37 yr) vs. older (73 yr) adults. Serum creatine kinase was elevated 46% 24 h after RL in all subjects with no age differences, indicating similar degrees of myofiber membrane wounding by age. Despite this similarity, from genomic microarrays 318 unique transcripts were differentially expressed after RL in old vs. only 87 in young subjects. Follow-up pathways analysis and functional annotation revealed among old subjects upregulation of transcripts related to stress and cellular compromise, inflammation and immune responses, necrosis, and protein degradation and changes in expression (up- and downregulation) of transcripts related to skeletal and muscular development, cell growth and proliferation, protein synthesis, fibrosis and connective tissue function, myoblast-myotube fusion and cell-cell adhesion, and structural integrity. Overall the transcript-level changes indicative of undue inflammatory and stress responses in these older adults were not mirrored in young subjects. Follow-up immunoblotting revealed higher protein expression among old subjects for NF-κB, heat shock protein (HSP)70, and IL-6 signaling [total and phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3 at Tyr705]. Together, these novel findings suggest that young and old adults are equally susceptible to RL-mediated damage, yet the muscles of older adults are much more sensitive to this modest degree of damage—launching a robust transcriptome-level response that may begin to reveal key differences in the regenerative capacity of skeletal muscle with advancing age.

Keywords: resistance exercise, aging, microarray, inflammation

while skeletal muscle is recognized as an exceptionally plastic tissue, aging skeletal muscle demonstrates an impaired capacity for regeneration when exposed to the same injury stimulus as young muscle, as shown definitively in rodent models (13, 14, 39). This creates a concern for older adults as they transition toward frailty and/or attempt to recover from surgery, because sarcopenia (i.e., age-related skeletal muscle atrophy) is exacerbated in these patients and they are unable to restore affected muscle mass to presurgery levels despite intensive physical intervention (48).

Postnatal skeletal muscle repair and regeneration following acute injury (e.g., high-intensity exercise bout, trauma, surgery, drug-induced necrosis) involves a complex array of coordinated activities that is incompletely understood. On the other hand, it is widely accepted that muscle progenitor cell [satellite cell (SC)] recruitment is a key component of the process, indicating that at least some aspects of developmental (secondary) myogenesis are recapitulated during postnatal muscle regeneration (35, 54). The nominally quiescent SCs reside just outside of the myofiber sarcolemma beneath the basal lamina and are thus architecturally positioned to respond rapidly to cues from the circulation, the extracellular matrix, and secreted factors exiting nearby myofibers (28). The appropriate regeneration response involves SC proliferation; progression along a myogenic lineage to differentiated, fusion-competent myoblasts; and fusion to injured, repairing myofibers as nuclear donors or, with overt damage (e.g., trauma, surgery), myoblasts fuse with one another to form multinucleated myotubes that then develop into replacement myofibers. These SC functions and their molecular regulation are described in a number of excellent reviews (10, 35, 51, 54). Although the precise mechanisms are not fully understood, SC function is clearly impaired with advancing age as shown in both human (8) and rat (4) primary SCs. Furthermore, in vivo aging rodent studies have demonstrated that SC recruitment is impaired during atrophy countermeasures (23) and SC-mediated regeneration following damage is less effective (13, 14), which is at least partially caused by the aging SC niche (14). Concurrent to the initiation of regenerative mechanisms after skeletal muscle injury is an induction of inflammatory and stress responses (19, 27, 55) including an infiltration of macrophages (2, 12). These responses may “jump-start” regeneration; however, prolonged or hyperelevated proinflammatory cytokine signaling impedes the process (42). Furthermore, inhibiting the conversion of invading macrophages to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype impairs muscle regeneration (52). A better understanding of the principal mechanisms driving skeletal muscle regeneration is essential to fully appreciate key alterations in the aging muscle that cause disruption.

Microarray analysis allows for comprehensive and simultaneous assessment of all skeletal muscle transcripts and provides a unique opportunity to identify age-dependent changes in the skeletal muscle transcript profile after a stressor or injury stimulus [e.g., unaccustomed resistance loading (RL)] that might have otherwise been unidentified. While a few transcript profiling studies of resistance exercise-mediated changes have been published (31, 38, 41, 50, 60), none has tested differential age responses to contraction-mediated damage across the entire transcriptome, because these studies were conducted in younger men only (38, 60), were long-term training studies (41, 50), or did not assess changes in the whole transcriptome (31).

The purpose of this study was therefore to determine, by genomewide microarray analysis including functional gene networks and pathways analysis, whether young and old adults respond differentially to a standardized bout of unaccustomed RL sufficient to induce moderate muscle damage. Our overarching hypothesis was that any age differences in the transcriptome-level response may reveal key factors responsible for the muscle regeneration impairment among the old.

METHODS

Forty-six young and older men and women were studied (subject characteristics in Table 1). Health history and physical activity questionnaires were completed by all participants during screening. Participants in the older group also passed a comprehensive physical exam and a diagnostic, graded exercise stress test with 12-lead ECG. Subjects were excluded for any musculoskeletal or other disorders that might have affected their ability to complete the RL bout and testing for the study; obesity [body mass index (BMI) > 30.0 kg/m2]; knee extensor resistance training within the past 5 yr; and treatment with exogenous testosterone or other pharmacological interventions known to influence muscle mass or muscle recovery. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and the Birmingham Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center. All subjects provided written informed consent before participation.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics and serum levels of creatine kinase and inflammatory cytokines before and 24 h after resistance loading

| Old |

Young |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-RL | Post-RL | Pre-RL | Post-RL | |

| Subject characteristics | ||||

| Age, yr | 73 ± 1* | 37 ± 1 | ||

| Weight, kg | 72.4 ± 2.1 | 76.6 ± 2.6 | ||

| LBM, kg | 43.97 ± 1.90* | 50.35 ± 2.30 | ||

| Creatine kinase, U/l | 117.3 ± 23.0 | 171.1 ± 31.5† | 128.4 ± 14.8 | 187.7 ± 26.6† |

| IL-6, pg/ml | 1.44 ± 0.21 | 1.78 ± 0.25† | 1.12 ± 0.14 | 1.40 ± 0.21† |

| TNF-α, pg/ml | 4.11 ± 0.63 | 4.21 ± 0.68 | 3.68 ± 0.39 | 3.75 ± 0.40 |

| IL-8, pg/ml | 10.88 ± 1.48 | 10.90 ± 1.33 | 10.58 ± 2.68 | 11.21 ± 2.41 |

Values are means ± SE for 22 and 24 (subject characteristics), 20 and 19 (creatine kinase levels) and 19 and 20 (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-8 levels) old and young subjects, respectively. RL, resistance loading; LBM, lean body mass.

Different from young, P < 0.05.

Different from baseline, P < 0.05.

Unaccustomed resistance loading bout.

Mechanical overload of the knee extensor muscle group was accomplished by a standardized RL bout designed specifically to induce moderate myofiber wounding, because subjects were untrained and unaccustomed to the RL. The RL bout consisted of 9 sets of ∼10 repetitions of bilateral, concentric-eccentric knee extension contractions against a constant external load on a conventional weight-stack knee extension machine. Subjects were instructed and encouraged throughout to perform the concentric phase of each repetition as rapidly as possible, followed by their best attempt to control the eccentric lowering phase. The external resistance set for each subject was equivalent to 40% of bilateral maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVC) force determined by a load cell and regression procedures as we have previously described (46). As demonstrated by >1,000 tests in our laboratory of combined bilateral MVC and dynamic one-repetition maximum (1RM) knee extension strength testing, the external load equivalent to 40% MVC approximates 60% 1RM (data not shown). The “intensity” of each contraction based solely on external load would therefore be considered moderate. However, key features of this protocol that increased overall intensity included the explosive concentric phase of each repetition and brief rest periods (<90 s) between sets. We have previously shown (46) by electrogoniometry that 10 successive repetitions of this protocol induce velocity-dependent muscle fatigue, particularly among old subjects.

Muscle biopsy and tissue preparation procedures.

Percutaneous needle biopsy of the vastus lateralis was taken with a 5-mm Bergstrom biopsy needle under local anesthetic (1% lidocaine) by previously described methods (11, 21). Muscle biopsies were performed in the morning after an overnight fast at baseline (pre-RL) and 24 h after RL (post-RL) in the resting state. The post-RL muscle biopsy was taken from the contralateral leg to avoid any residual effects of the pre-RL biopsy. Each biopsy was quickly blotted with gauze and dissected to remove any visible connective and/or adipose tissue. Muscle samples were divided into ∼30-mg portions, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Blood draws (10 ml from an antecubital vein) were performed in the fasting state at the same two time points, and serum was isolated and stored at −80°C.

RNA isolation and microarray analysis.

Genomic microarrays were performed on 16 subjects (8 young, 8 old) before and after RL; groups were balanced by sex (4 men, 4 women per age group). Total RNA was isolated and further purified from the frozen muscle samples with TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) and RNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), respectively, according to the manufacturers‘ instructions. RNA concentration was determined with a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop ND-1000). An aliquot from each sample of total RNA was shipped to either the Agilent Center for Excellence (Santa Clara, CA) or Cogenics (Morrisville, NC) for microarray analysis. Before sample processing, RNA quantity and quality of each sample were determined by spectrophotometry and an Agilent Bioanalyzer, respectively. The transcript profile of each purified RNA sample was determined with Agilent human 4X44K single-color arrays (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) containing >41,000 gene transcripts and the standard single-color array protocol at Agilent’s Center for Excellence and Cogenics. For standardization, pre- and post-RL samples within each subject were analyzed in the same batch and each batch included samples from both young and old subjects.

Immunoblotting.

Standard immunoblotting was performed with established methods in our laboratory (3, 33) on samples from 32 subjects (16 young, 16 old); groups were balanced by sex (8 men, 8 women per age group). Muscle protein lysate was extracted from frozen muscle samples (average 30–35 mg) as detailed previously (3, 32, 33). Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) technique with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Samples were run on 4–12% Bis-Tris (Invitrogen) SDS-PAGE gel matrices with 30 μg of total protein loaded into each well, which was determined as ideal by preliminary experiments. Samples within subjects across time were loaded in adjacent lanes. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes at 100 mA for 12 h. Primary antibodies of selected proteins of interest based on microarray results and gene network analyses included total signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3, phospho-STAT3(Ser727), phospho-STAT3(Tyr705), total NF-κB p50, total IκBα, phospho-IκBα(Ser32/36), phospho-Iκκα/β(Ser176/180), heat shock protein (HSP)27, and HSP70 (Cell Signaling Technologies, Beverly, MA). Appropriate primary antibody concentrations were determined in preliminary experiments and were 1:1,000 (vol/vol). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was used at 1:50,000 (wt/vol), followed by chemiluminescent detection in a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc imaging system with band densitometry performed with Bio-Rad Quantity One (software package 4.5.1, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Parameters for image development were consistent across all membranes by predefined saturation criteria as described previously (3).

Serum cytokines and creatine kinase.

Circulating concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-1β, IL-8, and TNF-α were determined by ELISA on 39 subjects [20 young (10 men, 10 women); 19 old (9 men, 10 women)] with MS2400 Human Pro-Inflammatory 4-Plex II Ultra-Sensitive Kits (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD) and standard procedures. Samples were measured in triplicate. Serum creatine kinase (CK) activity was determined in 39 subjects [19 young (10 men, 9 women); 20 old (10 men, 10 women)] by a standard enzymatic rate method with the SYNCHRON DxC 800 system in the UAB Hospital Chemistry Laboratory. The baseline muscle biopsy was taken a minimum of 1 wk before the 24-h post-RL biopsy to prevent any residual effects of the baseline biopsy on circulating CK or cytokine levels.

Data analysis.

Baseline differences between the older and younger adults in subject characteristics and protein expression were determined by independent t-tests. A 2 × 2 (age × RL) repeated-measures ANOVA was used to test age, time, and age × time interaction effects for serum cytokines, CK levels, and muscle protein expression/phosphorylation with age and in response to RL (pre-RL vs. post-RL). Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) tests were performed post hoc as appropriate. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

Microarray data analysis was performed as follows. Normalization of raw data and comparative analysis between expression profiles were carried out with Genespring GX 10.0 (Agilent Technologies). The raw data were normalized with quantile normalization and filtering of the transcripts by “present” and “marginal” flags. A “present,” “absent,” or “marginal” was designated to a transcript based on signal intensity and background noise. A transcript was kept if it had a “present” or “marginal” call for 100% of the arrays in at least one of the two treatment groups (pre-RL or post-RL). This reduced the number of transcripts from 41,078 to 25,597 in the older adults and to 25,337 in the younger adults. A paired t-test was used to determine RL-mediated differences in gene expression within each age group (old and young) at a stringent P value of <0.001 to minimize type I errors. To provide biologically meaningful information to the transcript profile changes, all differentially expressed transcripts were functionally annotated with the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrative Discovery (DAVID, david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov) and Gene Ontology (GO, www.geneontology.org), and their interacting roles in networks, cellular functions, and canonical pathways were further analyzed with Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) 5.0 (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA).

RESULTS

There was a 46% increase in serum CK 24 h after RL in both the older and younger adults (P < 0.001, Table 1), indicating that the RL bout achieved the goal of modest damage to the quadriceps. Importantly, the degree of myofiber membrane wounding as indexed by serum CK was nearly identical in the two age groups. Additionally, post-RL there was an increase in circulating IL-6 in both the older and younger adults (P < 0.005, Table 1). There were no changes in circulating TNF-α or IL-8 levels (P > 0.05, Table 1). The multiplex plate that was used to determine changes in serum cytokine levels was not sensitive enough to sufficiently detect IL-1β in all samples.

Transcript profile results and functional annotation.

Average fold changes of the genes found to be differentially expressed (P < 0.001) within each age group after RL are summarized in Supplemental Table S1.1 After unaccustomed RL, 351 genes were differentially expressed (128 downregulated and 223 upregulated) among the older adults. Of these, 318 were unique transcripts (for internal validation, the Agilent chip contains more than one probe set targeting the same gene in some cases—thus we discarded redundant results). By contrast, only 91 transcripts (87 unique) were differentially expressed after RL in the younger group (36 downregulated and 55 upregulated). Furthermore, of the 318 in old and 87 in young subjects that were altered by RL, only 2 transcripts were commonly differentially expressed after RL in both young and old subjects: profilin 1 (PFN1; +1.2-fold in old, +1.1-fold in young) and tubulin α-8 (TUBA8; +1.6-fold in old, +1.2-fold in young). Using DAVID and GO databases, we functionally annotated the 318 and 87 unique differentially expressed transcripts for the older and younger adults, respectively, and these results are displayed in Supplemental Table S1.

Among old subjects, 25 of the differentially expressed genes were found to be associated with inflammation and stress. Of note, only four genes fell into this functional classification among young subjects. Stress responses in the older group included downregulation (range −1.4-fold to −2.1-fold) for several members of the antioxidant metallothionein family (MT1X, MT1G, MT1H, MT1B, MT1A), while four HSP family members were upregulated 1.3- to 1.6-fold (HSPA9, HSPE1, HSPB1, HSPH1). Among older adults, 11 proteolysis-related genes were differentially expressed after RL (7 upregulated +1.2 to +1.5-fold, 4 downregulated −1.2 to −1.5-fold) compared with only 3 among young adults. In older adults these included four components of the ubiquitin-proteasome—an E2 conjugating enzyme (UBE2G1), ubiquitin-specific peptidases 54 and 28 (USP54, USP28), and ubiquitin family domain containing 1 (UBFD1)—as well as two autophagy-related genes (ATG3, ATG4A). Among genes involved in transcriptional processes, altered expression was found for 17 genes in old and 5 in young adults. In the older adults, 10 of the 11 differentially expressed genes involved in translation were upregulated including the δ-subunit of eIF2B (+1.3-fold), eIF4E (+1.4-fold), and ribosomal protein S6 kinase-like 1 (RPS6KL1, +1.5-fold), while no changes in this functional group were seen among young adults. Nine of the differentially expressed genes among old adults were functionally grouped under structural integrity, including myosin binding protein H (MYBPH), which showed the most robust change across all transcripts (+4.1-fold). Under the broad grouping of genes related to cell cycle/cell proliferation, 13 genes were differentially expressed in old and 8 in young adults, yet none were common in both age groups.

Network analysis.

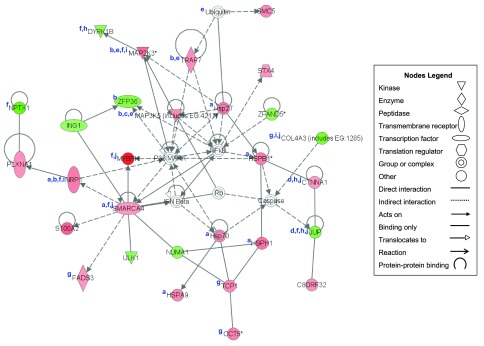

IPA was used to further characterize the age-specific responses to RL by clustering and scoring functional networks of differentially expressed transcripts. The maximum number of nodes allowed in an IPA network is 35. Among the older adults, we focused on the network with the highest score of 49 (P = 10−49) in which 29 of the 35 possible transcripts were differentially expressed after RL (Fig. 1 and Table 2). In agreement with the largest list of transcripts grouped via functional annotation, the two “hubs” of this network (NF-κB and p38 MAPK) gave a strong indication that inflammation and stress lay at the center of the primary skeletal muscle responses to unaccustomed RL among older adults. The translated protein products of transcripts within this network play key roles in stress and cellular compromise (HSPH1, HSPA9, HSP70, HSP27, HSPB1, SMARCA4, PLXNA1, NRP1); inflammation and immune responses (ZFP36, TRAF7, MAP2K3, MAP3K5, NRP1); necrosis (MAP3K5); protein synthesis (CTNNA1, JUP); protein degradation (TRAF7, ubiquitin, MAP2K3, MAP3K5); skeletal and muscular development (DYRK1B, MAP2K3, MYBPH, NRP1, SMARCA4, JUP, PLXNA1, NPTX1); cell growth and proliferation (TCP1, CCT5, FADS3, COL4A3); myoblast-myotube fusion and cell-cell adhesion (DYRK1B, CTNNA1, JUP); fibrosis and connective tissue function (PLXNA1, NRP1, COL4A3, MAP2K3); and structural integrity (MYBPH, SMARCA4, COL4A3, CTNNA1, JUP).

Fig. 1.

Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) Network 1 (score = 49) clustered 29 (of 35 in the network) of the resistance loading (RL)-mediated differentially expressed genes in older adults (n = 8) that are directly and indirectly interacting and relevant to stress and cellular compromise (a); inflammation and immune responses (b); necrosis (c); protein synthesis (d); protein degradation (e); skeletal and muscular development (f); cell growth and proliferation (g); myoblast-myotube fusion and cell-cell adhesion (h); fibrosis and connective tissue function (i); and structural integrity (j). Red, upregulated; green, downregulated; white, not differentially expressed but related to this network. *Transcript represented by multiple probe sets. EG, Entrez Gene No. or GeneID. Two heat shock proteins (HSPs) inserted into the network by IPA, HSP27 and HSP70, are synonymous with the differentially expressed HSPB1 and HSPA9, respectively. Such redundant entries occur by default in IPA's automated networking function if a gene within, or synonymous with, a larger “group” enters the network (HSPA9 is synonymous with, or within, the HSP70 group, which contains 11 members; HSPB1 is synonymous with, or within, the HSP27 group, which contains 4 members).

Table 2.

Summary of resistance loading-mediated differentially expressed genes (P < 0.001) in older adults (n = 8) identified in Network 1

| Name | Description | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|

| C8ORF32 | Chromosome 8 open reading frame 32 | 1.2 |

| CCT5 | Chaperonin containing TCP1, subunit 5 (ε) | 1.4 |

| COL4A3 | Collagen, type IV, α3 (Goodpasture antigen) | −1.7 |

| CTNNA1 | Catenin (cadherin-associated protein), α1, 102 kDa | 1.2 |

| DYRK1B | Dual-specificity tyrosine-(Y)-phosphorylation regulated kinase 1B | −1.4 |

| FADS3 | Fatty acid desaturase 3 | 1.2 |

| HSPA9 | Heat shock 70-kDa protein 9 (mortalin) | 1.3 |

| HSPB1 | Heat shock 27-kDa protein 1 | 1.5 |

| HSPH1 | Heat shock 105-kDa/110-kDa protein 1 | 1.6 |

| ING1 | Inhibitor of growth family, member 1 | −1.2 |

| JUP | Junction plakoglobin | −1.5 |

| MAP2K3 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3 | 1.7 |

| MAP3K5 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 5 | 1.4 |

| MYBPH | Myosin binding protein H | 4.1 |

| NPTX1 | Neuronal pentraxin I | −2.4 |

| NRP1 | Neuropilin 1 | 1.5 |

| NUMA1 | Nuclear mitotic apparatus protein 1 | −1.3 |

| PLXNA1 | Plexin A1 | 1.3 |

| S100A2 | S100 calcium binding protein A2 | 1.8 |

| SMARCA4 | SWI/SNF-related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 4 | 1.2 |

| SMC5 | Structural maintenance of chromosomes 5 | 1.3 |

| STX4 | Syntaxin 4 | 1.2 |

| TCP1 | T-complex 1 | 1.3 |

| TRAF7 | TNF receptor-associated factor 7 | 1.3 |

| ULK1 | Unc-51-like kinase 1 | −1.3 |

| ZFAND5 | Zinc finger, AN1-type domain 5 | −1.4 |

| ZFP36 | Zinc finger protein 36, C3H type, homolog | −1.5 |

| Caspase* | Caspase | NA |

| IFN Beta* | Interferon β | NA |

| NF-κB* | Nuclear factor-κB | NA |

| P38 MAPK* | p38-Mitogen-activated protein kinase | NA |

| Rb* | Retinoblastoma | NA |

| Ubiquitin* | Ubiquitin | NA |

Nondifferentially expressed transcript identified by Ingenuity Pathways Analysis as either a hub or a connecting node that connects other nodes within the network. NA, not applicable.

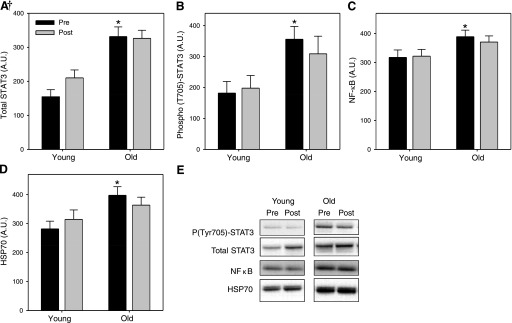

Protein-level analysis.

Proteins were selected for follow-up immunoblotting based on microarray results that suggested stress- and cytokine-mediated inflammation among old subjects after RL. While no RL-mediated changes in protein content or phosphorylation state were found at the 24 h time point, some remarkable age differences in the resting muscle were identified and are described below. These age differences in protein expression at baseline suggest that the muscles of old adults are “primed” for a stress response and therefore may have a heightened sensitivity to cellular stress and inflammation.

IL-6 signaling is transduced largely via phosphorylation and activation of the transcription factor STAT3. While circulating IL-6 increased similarly (∼25%) in old and young subjects after RL, STAT3 mRNA increased (1.4-fold) among old subjects only. We therefore quantified total and phosphorylated STAT3 protein in muscle lysate and found remarkably higher baseline levels of both total (+114%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A) and phosphorylated (Tyr705 +96%, P < 0.005) (Fig. 2B) STAT3 protein in old versus young subjects. Phosphorylation at Tyr705 induces STAT3 dimerization and nuclear localization. Ser727 phosphorylation, also required for transcriptional activation, was not different by age (not shown). STAT3 total protein increased 35% in young subjects after RL (P < 0.05) but remained substantially lower than the total STAT3 levels seen among old subjects.

Fig. 2.

Effects of age and RL on protein content or phosphorylation [optical density, arbitrary units (AU)] of the selected target proteins including: signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT3) (A); phospho-STAT3 (B); NF-κB (C); and 70-kDa heat shock protein (HSP70) (D). E: representative immunoblots. Immunoblotting was performed with samples from 16 young and 16 older adults. *Different from young at baseline, P < 0.05; †age × RL interaction, P < 0.05.

Muscle transcript-level changes suggested the potential for increased RL-mediated muscle TNF activity including a 1.3-fold upregulation of TNF receptor-associated factor 7 (TRAF7) in older adults and a 1.2-fold upregulation of TRAF and TNF receptor-associated protein (TTRAP) in young adults. Furthermore, NF-κB, a transcription factor largely responsible for mediating the stress-activated catabolic effects of TNF-α downstream of the TNF receptor, emerged as a central hub in Network 1 for the older adults. We therefore assessed protein levels of NF-κB (p50) and found 26% higher protein content in old versus young adults (P < 0.05) at baseline (Fig. 2C) but no age differences in the phosphorylation states of IκBα and Iκκα/β (not shown).

The transcriptome response of older adults revealed robust upregulation of several HSP family members, suggesting a reaction to cellular stress. Consequently we assayed muscle protein lysate for two of the HSPs appearing in Network 1—70-kDa (HSPA9 or HSP70) and 27-kDa (HSPB1 or HSP27) HSPs—after finding transcript-level increases of +1.3 and +1.5-fold, respectively, post-RL among older adults. Similar to the transcription factors mediating inflammation (STAT3, NF-κB), HSP70 protein content was greater (41%) among old versus young adults at baseline (P < 0.01, Fig. 2D). There were no age differences for HSP27 (not shown). Representative immunoblots are shown in Fig. 2E.

DISCUSSION

Differentially expressed genes in older and younger adults, increased serum CK, and increased circulating IL-6 suggest that the unaccustomed high-intensity RL bout was sufficient to induce moderate damage in the skeletal muscle and initiate changes in the skeletal muscle transcriptome, particularly among older adults. We find it remarkable that, after the same mechanical stress, 318 genes were differentially expressed among old versus only 87 genes among young adults, with the two age groups showing similar changes in only two genes. These age differences in response to RL occurred despite similar degrees of myofiber membrane wounding as indexed by nearly identical percent increases in serum CK. The value of this finding should not be overlooked, as it indicates that the myofibers of older adult muscle were not more susceptible to mechanical membrane damage, yet they responded to the insult with a remarkably different gene expression profile that may help us begin to understand why regenerative function is impaired in the old as shown in rodent models (13, 14, 39).

Follow-up analyses centered on the a priori assumption that mechanical load-induced transcriptome changes unique to the old may underlie causes of age-related regeneration impairment, thus identifying attractive candidates for targeted studies. We therefore focused on the IPA network with the highest score (i.e., significance) among the old only. The two hubs of this network, NF-κB and p38 MAPK, suggest that inflammation and stress lay at the center of the primary skeletal muscle responses among the old.

Repair and regeneration.

Skeletal muscle regeneration following injury appears dependent on the recruitment of resident SCs and/or other stem cell populations capable of differentiation along the myogenic lineage to fusion-competent myoblasts (15). These myoblasts then fuse as nuclear donors to damaged myofibers or, at sites of necrosis or severe damage, fuse to one another to form myotubes that differentiate into replacement fibers (10). We identified a few differentially expressed transcripts in the older adults 24 h after RL that may negatively impact SC-mediated processes during the subsequent recovery period (e.g., 48–96 h). For example, neuronal pentraxin 1 (NPTX1) and DYRK1B/Mirk (minibrain-related kinase) were downregulated −2.4 and −1.4 fold, respectively. NPTX1 is transcriptionally activated by the myogenic transcription factor MyoD in proliferating myoblasts (59), while DYRK1B is a Rho-induced kinase highly expressed in skeletal muscle that promotes myoblast fusion (18), and its expression normally increases coordinate with myogenin during myogenesis. Cell-cell adhesion is modulated by catenin α1 (CTNNA1) and one of its binding partners, junction plakoglobin (JUP). Although CTNNA1 increased slightly (1.2-fold), JUP was downregulated (−1.5-fold). Furthermore, calpastatin, a calpain inhibitor, inhibits fusion and is normally downregulated during differentiation (6, 7) but was increased (1.3-fold). Collectively the differential expression of these genes at 24 h—among only the older adults—may negatively impact myoblast differentiation and fusion later during recovery when these processes are expected to be more prominent (e.g., 48–96 h).

Inflammatory and stress responses.

We interpret several transcript-level alterations found only in the older adults to be suggestive of undue stress and inflammatory signaling within the muscle, which may be partially responsible for muscle regeneration impairment. Pavlath (43) showed quite clearly in mice that overt inflammation impairs regeneration, as IFN-γ-mediated muscle inflammation induced expression of class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) in regenerating myofibers and attenuated regeneration. Analyzing a small number of target transcripts, two human studies indicate that aging alters the expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory genes in response to unaccustomed RL (20, 27). In the present study, the two main hubs within Network 1, NF-κB and p38 MAPK (Fig. 1), are intracellular intermediates of cytokine/stress signaling that are linked to numerous differentially expressed transcripts in Network 1. TNF-α and IL-1, two well-recognized proinflammatory cytokines with both systemic and local tissue effects, share common signaling pathways (NF-κB, SAPK/JNK, p38 MAPK). The upregulation after RL of TRAF7, a TNF receptor signal transducer and component of the ubiquitin ligase complex mediating protein degradation, along with higher levels of NF-κB protein in old versus young muscle despite no age differences in circulating TNF-α or IL-1, suggests heightened sensitivity in the older muscles to cytokine levels and/or cellular stresses. This concept is supported by recent evidence in rat primary SCs from old (vs. young) animals showing increased susceptibility to TNF-α induced proapoptotic signaling (36). Furthermore, in mice aging has been associated with greater stress-induced muscle expression of TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 (40). Muscle expression of TNF-α or IL-1 is also elevated in aging humans (25), and in aging rats increased TNF-α signaling (via NF-κB) induces apoptotic signaling, primarily in type II myofibers (47). Both TNF-α and IL-1 suppress protein synthesis in myoblasts and do so via a common second messenger, ceramide (53). Additional rodent data provide evidence that TNF-α promotes muscle protein degradation by increasing expression of the E3 ubiquitin ligase MuRF1 (1) and concomitantly impairs muscle protein synthesis by inhibiting mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated translation initiation (34). In the present study, PANX1, which regulates the release of IL-1 isoforms α and β (44), was robustly upregulated among old (2.9-fold) adults. Like TNF, IL-1 has been shown to induce muscle atrophy and inhibit protein synthesis, at least in part by blunting the expression of the ε-subunit of eIF2B (eIF2Bε) (16). Finally, MAP kinases in Network 1 that were upregulated include MAPKK3 (MAP2K3; 1.7-fold) and MAPKKK5 (MAP3K5; 1.4-fold); both are intermediates in the transduction of several cytokine-mediated inflammatory and cell stress responses including SAPK/JNK signaling, necrosis, and caspase-mediated apoptosis. The upregulation of MAP3K5 in muscle after unaccustomed RL persists for at least 48 h (38).

Increased expression of IL-6 is a common finding following mechanically induced muscle damage (55). There is some debate as to whether IL-6 signaling is beneficial or inhibitory during the acute response to mechanical stress. In mice, IL-6 has recently been shown to increase the expression of HSP72 and HSP25 in response to stress (29), suggesting an acute protective effect. On the other hand, chronic exposure to elevated muscle IL-6 induces atrophy (26), blunts growth (9), and is commonly considered a potential contributor to age-related sarcopenia. Congruent with the TNF/NF-κB results, our muscle protein-level analyses indicate much greater IL-6-associated signaling within muscle among older adults, despite no age differences in circulating IL-6. STAT3, the key transcription factor in IL-6 mediated JAK/STAT3 signaling as well as glucocorticoid receptor signaling, was upregulated 1.4-fold. Furthermore, a higher overall STAT3 protein level and state of STAT3 phosphorylation (Tyr705) among older adults suggests greater inflammatory signaling in the old even at rest. These findings again suggest that the older muscle may be more sensitive to any given amount of IL-6. Antimyogenic effects of IL-6 may be mediated at least partially by induced expression of the muscle E3 ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1/MAFbx and TNF-α (9). Recently in humans it has also been noted that acute mechanical stress robustly activates skeletal muscle STAT3 signaling (56), and, relevant to the present study, the investigators found that STAT3 phosphorylation was fivefold greater in old versus young while protein expression of the STAT3 antagonist suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-3 was repressed in the old (57).

Numerous members of the HSP family were upregulated among older adults as highlighted in Network 1. HSPs may play a role in degrading damaged proteins and maintaining cellular integrity after mechanical load-induced muscle injury. That we found higher HSP70 protein in the resting muscles of older adults and a greater HSP response to RL at the mRNA level suggests that the muscles of the old may be more actively remodeling to maintain integrity at rest, and may sense a greater need for HSP-mediated protection in response to the mechanical perturbation imposed by RL. Among young adults, the single HSP transcript that was upregulated (heat shock 70-kDa protein 1-like, HSPA1L) in the present study has been reported to be robustly induced in young men 3 h after a bout of 300 maximal eccentric contractions (38). Why this particular HSP transcript was unchanged in old subjects and appears to be consistently upregulated in young subjects after RL is unclear at this point. Overall, however, a far greater HSP response at the mRNA level was found among the old.

Five metallothionein (MT) isoforms (1A, 1B, 1G, 1H, and 1X) were downregulated (1.4- to 2.1-fold) in the older adults after RL. MTs play a protective role against oxidative stress, apparently as free radical scavengers, as heavy metal “buffers,” and/or by upregulating the expression of antioxidant enzymes (37). Five additional transcripts that function in metal ion binding were downregulated only among the old, including phosphodiesterase 11A (PDE11A), which was down 2.5-fold (see Supplemental Table S1). In prior studies of young men, seven MTs were upregulated after endurance exercise, presumably from the oxidative stress (37); however, when young men underwent a single bout of high-intensity eccentric RL, only one MT was differentially expressed and was downregulated (38). The oxidative nature of endurance exercise compared with RL suggests that the MTs may perhaps play different roles in stress management during recovery. Why MT expression was downregulated 24 h after RL among old subjects only is as yet unclear; however, this may be yet one more indication that the RL stimulus was much more of a stress in the old since the present literature suggests that a substantially higher degree of mechanical stress is required to elicit MT downregulation in the young (38).

Protein metabolism.

Among older adults we found significantly increased mRNA expression of factors involved in translation, including eIF2Bδ (1.3-fold), eIF4E (1.4-fold), and ribosomal protein S6 kinase-like 1 (RPS6KL1; 1.5-fold); on the other hand, expression of the upstream negative regulator—protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A)—was concurrently increased (1.4-fold). PP2A inhibits protein synthesis by dephosphorylating the mTOR targets 4EBP1 and p70S6K1, and, in fact, there is some evidence that mTOR's kinase action on these two targets may not be direct but rather results from restraining PP2A via mTOR phosphorylation (inhibition) of PP2A (45). Additionally, PP2A may impair protein synthesis by directing ubiquitination of p70S6K1 (58). AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling is also known to counteract Akt/mTOR signaling, and the γ-2 subunit of AMPK (PRKAG2) increased 1.5-fold among the old. The chaperone HSP27, also upregulated among the old, inhibits protein synthesis by binding eIF4G and thus preventing assembly of the eIF4F cap-binding initiation complex (17).

Among older subjects, several components of the Ub-proteasome system were differentially expressed after RL, including the peptidases USP28 (+1.5-fold) and USP54 (−1.3-fold), an E2 conjugating enzyme (UBE2G1; −1.4-fold), and UBFD1 (−1.2-fold). At this point the nature of these transcript-level changes in the translational machinery and Ub-proteasome system among only the older subjects is unclear, yet these data provide further evidence that the RL bout was interpreted by the muscles of old subjects as a much more potent stimulus of transcriptional activity.

Structural integrity of skeletal muscle.

Some noteworthy genes that were differentially expressed only in older subjects after RL support the concept that the muscles of older subjects may have experienced a degree of stress far exceeding that in young subjects despite being exposed to the exact same stressor. For example, gene expression of MyBPH was robustly elevated (4.1-fold) in the old only, as was myosin head domain containing 1 (MYOHD1; 1.4-fold). MyBPH is an integral myosin binding partner in the A band of myofibrils that interacts with the myosin rods and titin to provide structural integrity to the contractile apparatus. Reduced MyBPH expression is associated with muscle weakness in age-related disorders (30). Interestingly, localization of MyBPH to the contractile apparatus is directed by its C terminal domain consisting of two fibronectin type III motifs (24), and our microarray analysis also revealed a 1.6-fold increase among the old in the expression of fibronectin type III domain containing 3B (FNDC3B). As shown in mice, MyBPH is upregulated in the young after more intense eccentric loading (5), again suggesting age differences in the degree of mechanical stress required to activate many of these transcriptional responses (with young muscles requiring greater stress than old). MyBPH expression is modulated by the transcription factor SMARCA4 (SWI/SNF-related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 4), which was also significantly upregulated in the old only. Interestingly, SMARCA4 is activated by glucocorticoid receptor signaling and, in turn, regulates the expression of notable muscle-specific genes including myogenin, troponin T, and MyBPH. A strain on muscle integrity among the old was also suggested by significant downregulation (−1.7-fold) of both type IV collagen α3 (COL4A3) and α4 (COL4A4) mRNA expression and 1.6-fold upregulation of TUBA8. Type IV collagen, a major constituent of basement membranes, is degraded by matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) in response to muscle damage (49). These findings suggest that the muscles of the older subjects may have been attempting to launch a compensatory effort to maintain structural integrity—a response to this degree was apparently not sensed as necessary among the younger subjects.

Limitations.

While we feel that the results revealed from this study reveal valuable information on postexercise inflammatory and regenerative responses in older adults, there are limitations. We recognize that changes in the skeletal muscle transcript profile in response to exercise are transient (38) and that the single time point of 24 h after RL limits our ability to detect early, more transient changes. Differential responses between older and younger adults could therefore be partially due to timing; however, previous transcript profiling studies in younger adults do not demonstrate such marked stress and inflammatory responses even at earlier time points after RL (38, 60). Microarray analysis of RNA isolated from tissues of mixed cellularity such as skeletal muscle is complicated by the loss of cellular and spatial information defining the signal origin (22). While the bulk of RNA isolated from muscle tissue is derived from myonuclei, age differences in the abundance of other contributing cell types could be an important factor that was not controlled. This possible confounder, however, should have been minimized since our analysis focused on within-subject changes in response to RL (rather than cross-sectional age group comparisons). Microarray technology itself is not without inherent limitations, including background noise and the sensitivity and specificity of probes (22). We took great care to control for these issues by employing quantile normalization and by filtering (flagging) the transcripts based on signal intensity and background noise. Finally, the number of samples/subjects analyzed via microarray did not allow us to statistically test interactions between age and RL, and the conservative significance value of P < 0.001 for within-group testing certainly constrained the number of significant findings. It is clear, however, that the RL-mediated changes in the transcript profile between the older and younger adults were different.

Summary.

We have described, for the first time, marked age differences in the genomewide transcriptome response to a standardized, unaccustomed bout of RL. Together, the numerous age differences noted strongly suggest that the threshold of mechanical stress required to induce changes in the molecular signature of skeletal muscle is much lower in the old. The muscles of old (vs. young) adults were much more sensitive to an equal and modest degree of damage—launching a robust transcriptome-level response that may begin to reveal key differences in the regenerative capacity of skeletal muscle with advancing age. With nearly fourfold more genes differentially expressed in old versus young adults in response to RL, we found the muscle transcriptome of the old to be responsive across a wide array of functional gene groupings including inflammation and stress, repair, structural integrity, protein metabolism, apoptosis, and proliferation among others. These novel data provide an important basis for future investigations aimed to target age differences in specific cellular processes that may help us to better understand the impact of aging on muscle regenerative function.

GRANTS

This research was supported by a VA Merit Review Award (M. M. Bamman) and National Institutes of Health Grants 5R01-AG-017896 (M. M. Bamman), 5P50-HL-077100 (L. J. Dell'Italia), 2T32-DK-062710 (A. E. Thalacker-Mercer), and GCRC M01-RR-00032.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the participants for their efforts, and we thank S. C. Tuggle for administering the resistance loading stimulus.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adams V, Mangner N, Gasch A, Krohne C, Gielen S, Hirner S, Thierse HJ, Witt CC, Linke A, Schuler G, Labeit S. Induction of MuRF1 is essential for TNF-alpha-induced loss of muscle function in mice. J Mol Biol 384: 48–59, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arnold L, Henry A, Poron F, Baba-Amer Y, van Rooijen N, Plonquet A, Gherardi RK, Chazaud B. Inflammatory monocytes recruited after skeletal muscle injury switch into antiinflammatory macrophages to support myogenesis. J Exp Med 204: 1057–1069, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bamman MM, Ragan RC, Kim JS, Cross JM, Hill VJ, Tuggle SC, Allman RM. Myogenic protein expression before and after resistance loading in 26- and 64-yr-old men and women. J Appl Physiol 97: 1329–1337, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barani AE, Durieux AC, Sabido O, Freyssenet D. Age-related changes in the mitotic and metabolic characteristics of muscle-derived cells. J Appl Physiol 95: 2089–2098, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barash IA, Mathew L, Ryan AF, Chen J, Lieber RL. Rapid muscle-specific gene expression changes after a single bout of eccentric contractions in the mouse. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C355–C364, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barnoy S, Glaser T, Kosower NS. Calpain and calpastatin in myoblast differentiation and fusion: effects of inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1358: 181–188, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barnoy S, Glaser T, Kosower NS. The calpain-calpastatin system and protein degradation in fusing myoblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta 1402: 52–60, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bigot A, Jacquemin V, Debacq-Chainiaux F, Butler-Browne GS, Toussaint O, Furling D, Mouly V. Replicative aging down-regulates the myogenic regulatory factors in human myoblasts. Biol Cell 100: 189–199, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bodell PW, Kodesh E, Haddad F, Zaldivar FP, Cooper DM, Adams GR. Skeletal muscle growth in young rats is inhibited by chronic exposure to IL-6 but preserved by concurrent voluntary endurance exercise. J Appl Physiol 106: 443–453, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boonen KJ, Post MJ. The muscle stem cell niche: regulation of satellite cells during regeneration. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 14: 419–431, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chakravarthy MV, Davis BS, Booth FW. IGF-I restores satellite cell proliferative potential in immobilized old skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 89: 1365–1379, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chazaud B, Brigitte M, Yacoub-Youssef H, Arnold L, Gherardi R, Sonnet C, Lafuste P, Chretien F. Dual and beneficial roles of macrophages during skeletal muscle regeneration. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 37: 18–22, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, Smythe GM, Rando TA. Notch-mediated restoration of regenerative potential to aged muscle. Science 302: 1575–1577, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, Wagers AJ, Girma ER, Weissman IL, Rando TA. Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature 433: 760–764, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Conboy IM, Rando TA. Aging, stem cells and tissue regeneration: lessons from muscle. Cell Cycle 4: 407–410, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cooney RN, Maish GO, Gilpin T, 3rd, Shumate ML, Lang CH, Vary TC. Mechanism of IL-1 induced inhibition of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle. Shock 11: 235–241, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cuesta R, Laroia G, Schneider RJ. Chaperone hsp27 inhibits translation during heat shock by binding eif4g and facilitating dissociation of cap-initiation complexes. Genes Dev 14: 1460–1470, 2000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deng X, Ewton DZ, Pawlikowski B, Maimone M, Friedman E. Mirk/dyrk1b is a rho-induced kinase active in skeletal muscle differentiation. J Biol Chem 278: 41347–41354, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dennis RA, Trappe TA, Simpson P, Carroll C, Huang BE, Nagarajan R, Bearden E, Gurley C, Duff GW, Evans WJ, Kornman K, Peterson CA. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms are associated with the inflammatory response in human muscle to acute resistance exercise. J Physiol 560: 617–626, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dennis RA, Przybyla B, Gurley C, Kortebein PM, Simpson P, Sullivan DH, Peterson CA. Aging alters gene expression of growth and remodeling factors in human skeletal muscle both at rest and in response to acute resistance exercise. Physiol Genomics 32: 393–400, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Evans WJ, Phinney SD, Young VR. Suction applied to a muscle biopsy maximizes sample size. Med Sci Sports Exerc 14: 101–102, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Forster T, Roy D, Ghazal P. Experiments using microarray technology: limitations and standard operating procedures. J Endocrinol 178: 195–204, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gallegly JC, Turesky NA, Strotman BA, Gurley CM, Peterson CA, Dupont-Versteegden EE. Satellite cell regulation of muscle mass is altered at old age. J Appl Physiol 97: 1082–1090, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gilbert R, Cohen JA, Pardo S, Basu A, Fischman DA. Identification of the a-band localization domain of myosin binding proteins c and h (mybp-c, mybp-h) in skeletal muscle. J Cell Sci 112: 69–79, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Greiwe JS, Cheng B, Rubin DC, Yarasheski KE, Semenkovich CF. Resistance exercise decreases skeletal muscle tumor necrosis factor alpha in frail elderly humans. FASEB J 15: 475–482, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Haddad F, Zaldivar F, Cooper DM, Adams GR. IL-6-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. J Appl Physiol 98: 911–917, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hamada K, Vannier E, Sacheck JM, Witsell AL, Roubenoff R. Senescence of human skeletal muscle impairs the local inflammatory cytokine response to acute eccentric exercise. FASEB J 19: 264–266, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hawke TJ, Garry DJ. Myogenic satellite cells: physiology to molecular biology. J Appl Physiol 91: 534–551, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huey KA, Meador BM. Contribution of IL-6 to the Hsp72, Hsp25, and alphabeta-crystallin responses to inflammation and exercise training in mouse skeletal and cardiac muscle. J Appl Physiol 105: 1830–1836, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hundley AF, Yuan L, Visco AG. Skeletal muscle heavy-chain polypeptide 3 and myosin binding protein h in the pubococcygeus muscle in patients with and without pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 194: 1404–1410, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jozsi AC, Dupont-Versteegden EE, Taylor-Jones JM, Evans WJ, Trappe TA, Campbell WW, Peterson CA. Molecular characteristics of aged muscle reflect an altered ability to respond to exercise. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 11, Suppl: S9–S15, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kosek DJ, Kim JS, Petrella JK, Cross JM, Bamman MM. Efficacy of 3 days/wk resistance training on myofiber hypertrophy and myogenic mechanisms in young vs. older adults. J Appl Physiol 101: 531–544, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kosek DJ, Bamman MM. Modulation of the dystrophin-associated protein complex in response to resistance training in young and older men. J Appl Physiol 104: 1476–1484, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lang CH, Frost RA. Sepsis-induced suppression of skeletal muscle translation initiation mediated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. Metabolism 56: 49–57, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Le Grand F, Rudnicki MA. Skeletal muscle satellite cells and adult myogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19: 628–633, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lees SJ, Zwetsloot KA, Booth FW. Muscle precursor cells isolated from aged rats exhibit an increased TNF-alpha response. Aging Cell 22: 222–223, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mahoney DJ, Parise G, Melov S, Safdar A, Tarnopolsky MA. Analysis of global mRNA expression in human skeletal muscle during recovery from endurance exercise. FASEB J 19: 1498–1500, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mahoney DJ, Safdar A, Parise G, Melov S, Fu M, MacNeil L, Kaczor J, Payne ET, Tarnopolsky MA. Gene expression profiling in human skeletal muscle during recovery from eccentric exercise. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R1901–R1910, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marsh DR, Criswell DS, Carson JA, Booth FW. Myogenic regulatory factors during regeneration of skeletal muscle in young, adult, and old rats. J Appl Physiol 83: 1270–1275, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Meador BM, Krzyszton CP, Johnson RW, Huey KA. Effects of IL-10 and age on IL-6, IL-1beta, and TNF-alpha responses in mouse skeletal and cardiac muscle to an acute inflammatory insult. J Appl Physiol 104: 991–997, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Melov S, Tarnopolsky MA, Beckman K, Felkey K, Hubbard A. Resistance exercise reverses aging in human skeletal muscle. PLoS ONE 2: e465, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moresi V, Pristera A, Scicchitano BM, Molinaro M, Teodori L, Sassoon D, Adamo S, Coletti D. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibition of skeletal muscle regeneration is mediated by a caspase-dependent stem cell response. Stem Cells 26: 997–1008, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pavlath GK. Regulation of class I MHC expression in skeletal muscle: deleterious effect of aberrant expression on myogenesis. J Neuroimmunol 125: 42–50, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pelegrin P. Targeting interleukin-1 signaling in chronic inflammation: focus on P2X7 receptor and pannexin-1. Drug News Perspect 21: 424–433, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Peterson RT, Desai BN, Hardwick JS, Schreiber SL. Protein phosphatase 2a interacts with the 70-kDa s6 kinase and is activated by inhibition of fkbp12-rapamycin associated protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 4438–4442, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Petrella JK, Kim JS, Tuggle SC, Hall SR, Bamman MM. Age differences in knee extension power, contractile velocity, and fatigability. J Appl Physiol 98: 211–220, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Phillips T, Leeuwenburgh C. Muscle fiber specific apoptosis and TNF-alpha signaling in sarcopenia are attenuated by life-long calorie restriction. FASEB J 19: 668–670, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reardon K, Galea M, Dennett X, Choong P, Byrne E. Quadriceps muscle wasting persists 5 months after total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the hip: a pilot study. Intern Med J 31: 7–14, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Roach DM, Fitridge RA, Laws PE, Millard SH, Varelias A, Cowled PA. Up-regulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 leads to degradation of type IV collagen during skeletal muscle reperfusion injury; protection by the MMP inhibitor, doxycycline. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 23: 260–269, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roth SM, Ferrell RE, Peters DG, Metter EJ, Hurley BF, Rogers MA. Influence of age, sex, and strength training on human muscle gene expression determined by microarray. Physiol Genomics 10: 181–190, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rudnicki MA, Le Grand F, McKinnell I, Kuang S. The molecular regulation of muscle stem cell function. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 73: 323–331, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ruffell D, Mourkioti F, Gambardella A, Kirstetter P, Lopez RG, Rosenthal N, Nerlov C. A CREB-C/EBPbeta cascade induces M2 macrophage-specific gene expression and promotes muscle injury repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 17475–17480, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Strle K, Broussard SR, McCusker RH, Shen WH, Johnson RW, Freund GG, Dantzer R, Kelley KW. Proinflammatory cytokine impairment of insulin-like growth factor I-induced protein synthesis in skeletal muscle myoblasts requires ceramide. Endocrinology 145: 4592–4602, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tajbakhsh S. Skeletal muscle stem cells in developmental versus regenerative myogenesis. J Intern Med 266: 372–389, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tomiya A, Aizawa T, Nagatomi R, Sensui H, Kokubun S. Myofibers express IL-6 after eccentric exercise. Am J Sports Med 32: 503–508, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Trenerry MK, Carey KA, Ward AC, Cameron-Smith D. Stat3 signaling is activated in human skeletal muscle following acute resistance exercise. J Appl Physiol 102: 1483–1489, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Trenerry MK, Carey KA, Ward AC, Farnfield MM, Cameron-Smith D. Exercise-induced activation of STAT3 signaling is increased with age. Rejuvenation Res 11: 717–724, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang ML, Panasyuk G, Gwalter J, Nemazanyy I, Fenton T, Filonenko V, Gout I. Regulation of ribosomal protein s6 kinases by ubiquitination. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 369: 382–387, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wyzykowski JC, Winata TI, Mitin N, Taparowsky EJ, Konieczny SF. Identification of novel MyoD gene targets in proliferating myogenic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol 22: 6199–6208, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zambon AC, McDearmon EL, Salomonis N, Vranizan KM, Johansen KL, Adey D, Takahashi JS, Schambelan M, Conklin BR. Time- and exercise-dependent gene regulation in human skeletal muscle. Genome Biol 4: R61, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.