Abstract

Aims

To examine how a rural community profoundly affected by escalating rates of largely AIDS-related deaths of young and middle-aged people makes sense of this phenomenon and its impact on their everyday lives.

Methods

Data were collected in Agincourt subdistrict, Limpopo Province. Twelve focus groups were constituted according to age and gender and met three times (a total of 36 focus-group discussions [FGDs]). The FGDs explored sequentially people’s expectations of their lives in the “new” South Africa, their interpretations of the acceleration of death amongst the young and middle-aged, and their understandings of HIV/AIDS. Discussions were recorded, fully transcribed, and thematically analysed.

Results

Respondents acknowledged escalating death rates in their community, yet few referred directly to HIV/AIDS as the cause. Rather, respondents focused on the social and cultural causes of death, including the erosion of cultural norms and traditions such as cultural taboos on sex. There are many competing versions of what HIV/AIDS is, what causes it and how it is spread, ranging from scientific explanations to conspiracy theories. Findings highlight the relationship between AIDS and other traditional diseases with some respondents suggesting that AIDS is a new form of other longstanding illnesses.

Conclusions

This study points to the centrality of cultural explanations in understanding “bad death” (AIDS death) in the Agincourt area. Physical illness is understood to be a symptom of “cultural damage”. Implications of this for public health practice and research are outlined.

Keywords: Culture, death, generation, HIV/AIDS illness, indigenous health beliefs, public health, rural, sex, South Africa

Introduction

Despite the recent acceleration of AIDS epidemics in parts of Asia and Eastern Europe, South Africa still has the highest percentage of people infected with HIV in the world. It has also been the country with the most contested and complex politics of AIDS [1,2]. With the country’s President, Thabo Mbeki, taking up a position of AIDS denialism and the Minister of Health sceptical about the merits of antiretroviral treatment (promoting alternative therapies of vitamins, olive oil, lemon juice and beetroot), it is no wonder that there are many signs of uncertainty, confusion and conflict over the nature and effects of HIV/AIDS.

Yet, at the same time, the fact of escalating death rates is inescapable. The exact statistics have been questioned by those sceptical about the scientific orthodoxy, but the everyday experiences of South Africans across the cities, towns, and rural areas of the country bear witness to the increasing prominence of death and dying in the lives of the country’s people. This assertive salience of death, moreover, has come in the midst of the country’s celebrations of the promise of new life since the demise of apartheid in 1994: newfound opportunities and entitlements, hopes, and aspirations, previously denied to the country’s black majority by the tenets of apartheid’s discriminatory practices.

It was in this post-apartheid context, with its symbolically charged conjunction of life and death, and the political controversies surrounding the spread of HIV/AIDS, that we undertook research into the meanings of life and death in a rural area in Limpopo Province. Despite the enormity and prominence of the issue of death in post-apartheid South Africa, there has been little research conducted into the ways in which communities are living with it. This project aimed to examine how a rural community profoundly affected by escalating rates of “bad death” – that is, the deaths of young and middle-aged people, rather than the elderly, whose deaths are expected and unthreatening – made sense of this phenomenon and its impact on their everyday lives.

Research setting

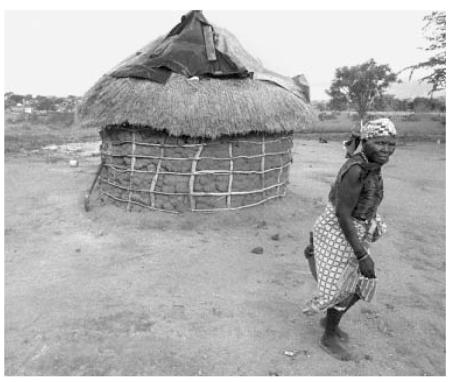

The Agincourt subdistrict of Bushbuckridge District, Limpopo Province comprises 21 villages and a population of some 70,000 people. It is situated in the rural northeast of South Africa, adjacent to the country’s border with Mozambique. The area is densely populated (170 persons per square kilometre), arid with low rainfall, and does not adequately support subsistence agriculture. Recent development activities have brought electricity to most villages and construction of a large dam; yet a minority can afford to purchase electricity, and piped water to households is not yet accessible. Labour migration is extensive as local employment opportunities are scarce: around 60% of men and 20% of women 35–54 years of age migrate from the area to work, or seek work, elsewhere [3]. The proportion of female-headed households is 29%. While primary school education is virtually universal, not all children continue to secondary school and only some 3% go on to any form of post-secondary education [4].

The MRC/Wits University Unit in Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research (Agincourt) has been monitoring births, deaths, and migrations in the Agincourt sub-district since 1992. During this period, mortality has worsened significantly for both sexes, with a rapid decline in life expectancy of 12 years in females and 14 years in males since 1997. The increases are most prominent in children under five years and younger adult (20–49) age groups, in which increases of two- and fivefold respectively have been observed in the past decade. Increases are more marked in females in most adult age groups [5].

Estimates of HIV seroprevalence, based on anonymous testing of pregnant women at antenatal clinics in the two provinces adjacent to the study site, indicate an increase for the area from about 1.7% in 1992 to 25% in 2003 (average for Mpumalanga and Limpopo Provinces) [6]. Within the Agincourt sub-district are five clinics and a health centre – all offer voluntary counselling and testing services although uptake is low – while three district hospitals are situated 25 to 60 km away. At the time of the study antiretroviral therapy was not available in public health services in the area. Most people access plural healthcare from allopathic health professionals, and traditional and faith healers [7].

Public health challenges: pointers from the literature

Since the onset of the epidemic, public health practitioners in South Africa have been central to the development of appropriate HIV/AIDS education and prevention campaigns [8-10]. Historically, the biomedical model has dominated public health efforts, overwhelmingly influencing explanations of the cause, appropriate intervention, and treatment of HIV/AIDS [11]. Heald argues that the acceptance of biomedical models of the disease has been so much at the forefront that other understandings have been subdued [12]. The language of AIDS, Heald suggests, is the language of Western science and policy. The consequences of this are many. AIDS intervention and prevention campaigns have often ignored the social and cultural contexts in which they have been implemented. The absence of local social knowledge around sexual norms and taboos has often resulted in short-sighted and limited interventions [12,13]. For example, the “safer-sex” model of prevention through urging greater condom use assumes that, once given the facts, people will change their sexual practices to avoid HIV. This ignores social (including gender) circumstances [14-17]. Efforts to incorporate peer education and community-based models of HIV/AIDS prevention have offset the focus of top-down, individual approaches [18-20]. So too have public health projects that co-locate HIV/AIDS programmes within broader sexual and reproductive health and primary healthcare initiatives [21,22]. Yet, the paradox of high AIDS awareness and high-risk sexual behaviour (practices) remains largely unchanged [23].

Clearly, then, the prospect of an effective public health intervention would depend on ethnographically dense renditions of local knowledge in respect of AIDS and its impact, proliferating pain, suffering, and death. The study we undertook was mindful of this challenge, and its methodological implications.

Study design

The study was an interdisciplinary venture, synthesizing perspectives and insights from public health and the social sciences. It was planned as evolving through two phases of qualitative research. This paper deals only with the first phase of the project, running for 14 months from early 2003. The research involved 36 focus groups, structured by age and gender. Two lay fieldworkers, one male and one female, well trained and highly skilled in qualitative data collection, facilitated the focus-group discussions (FGDs). Groups were conducted in the vernacular, and then translated into English. The discussions were recorded, fully transcribed, and thematically analysed. The focus groups were constituted according to criteria of age and gender, to produce six groups of men and six groups of women, from a number of rural villages in the Agincourt community. These sets of male and female groups were in turn structured by age, giving two groups aged 18–21; two groups aged 22–35; and another two aged 45–60, for each gender. Additional criteria that informed the sampling for the FGDs were that the young group comprised school-going youth who did not yet have children, the middle-aged group comprised adults with at least one child, while the older group had members with grand-children. All participants in the focus groups were asked to fill out a brief questionnaire, listing inter alia age, religious affiliations, and level of education.

Each group comprised 6–8 members, and each met three times, with the same membership throughout. Each discussion was constituted around a distinct theme. The first dealt with the participants’ expectations of life in the “new” democratic South Africa (i.e. post-1994); the second focused on their versions of the acceleration of death in their communities, and their responses to it; and the third dealt with the ways in which HIV/AIDS was understood and spoken – or not spoken – about. The sequencing was deliberate, starting with the least sensitive and contentious conversation and building up to a discussion about AIDS, known to be the site of powerful silences and anxiety. The intention was to allow for some rapport and familiarity to build up in each group through the three meetings, to promote a more open engagement with the AIDS issue than had the group simply plunged into it directly.

Key findings

Expectations of life in a time of AIDS

All the FGDs emphasized that life had been conspicuously different since 1994. For some, these changes were positive ones associated with bold aspirations to a prosperous and successful future; for others, the shifts were more ominous signs of social dislocation and deepening despair. It was the middle-aged and older men and women, in particular, whose musings on their lives and future prospects were typically more sombre. Having initially had high expectations of better lives under the new democratic dispensation, many of these men and women voiced their sadness and disillusionment with their lot. “Today we suffer as a result of the present government”, remarked one of the older men (pilot FGD 2, older men). “Freedom”, from this perspective, had brought worsening poverty, generational conflict, and moral disorder, all of which were closely connected to “different kinds of diseases [which are] difficult to understand” (FGD 28, older men). For the women, many of whom were shouldering the material and emotional burdens of caring for sick children and grandchildren, financial anxieties loomed large: “it is difficult to live if you do not have money” (FGD 34, older women). The men, typically, were particularly preoccupied with the ways in which their authority and social position were being eroded by the rights allocated to women and children in the country’s democratization process. A recurring theme throughout the FGDs with both the men and women in the middle and older age groups was their lament at the erosion of “tradition”, and the consequent damage done to the social body, along with the individuals within it.

The younger men and women expressed a stronger sense of their agency and capacity to shape a new future for themselves. But even so, their response to their new-found “liberation” was surprisingly ambivalent. While exulting in the opportunities that had been denied to their parents, many were nevertheless concerned that their democratic rights were being “misused”, resulting in a “lack of respect” for established norms and patterns of authority (FGD 4, young men).

Overall, then, the FGDs yielded an overwhelming perception of a society in the throes of dramatic changes but with discrepant, as well as internally ambivalent, renditions of these changes – as life-giving or life-sapping. And their different evocations of the manner of life since 1994 led, in turn, to different explanations for the recent profusion of death – as discussed below. But either way, these discussions of life in the post-apartheid milieu evoked an environment within which illness and subsequent death proliferates. Despite the advent of democracy in South Africa and its promise of “a better life for all” – in the perceptions of some, as a consequence of democratization – a heightened sense of the fragility of life infuses the experience of everyday life in Agincourt.

Understandings of the acceleration of “bad” death

In no FGD did any participant deny or dispute the recent escalation of death in their community; indeed, every FGD confirmed that the phenomenon was well known, and a source of often grave concern for people in the area.

Each series of FGDs raised the question of rising death rates before moving on explicitly to asking people about AIDS. There were two main reasons for this sequencing. The first was to assess the extent to which AIDS was spontaneously mentioned as the cause of the deaths, and the second was to postpone the overt engagement with AIDS until last, in the hope that the two prior discussions in each group would have established enough of a sense of mutual rapport to transcend the dominant social taboos on open and explicit discussion of the epidemic.

It is significant, then, that the explanations for the changing death rate seldom referred directly to AIDS as its cause. For some respondents, these changes had no coherent or clear explanation. “We really are puzzled by the way in which death occurs”, admitted one of the middle-aged male respondents, evoking agreement from some of the others in his group. “We do not know what to do because death is hunting for us in many ways” (FGD 17, middle-aged men). This uncertainty, and sense of the mysteriousness of these new patterns of mortality, was linked, too, to expressions of anxiety, fear (FGD 26, older men), and, in some instances, a suspicion that the public health services were now deliberately setting out to kill people.

The majority of respondents, however, did volunteer explanations for the rampant “bad death” in their communities. A few respondents – mostly women – referred to the variety of illnesses from which people currently suffer, including AIDS (FGD 33, older women), stressing the extent to which the multiplicity of diseases was a recent phenomenon.

Now there are … many kinds of illnesses; in the past there were no diseases. We are dying today. (FGD 34, older women)

Now there are many diseases and all these diseases occurred after [the 1994] elections. (FGD 34, older women)

Women also referred to poor diet, lack of exercise, and the absence of nutritious foods (a consequence of the fact that people are less inclined nowadays to grow their own and rely more on the nutritionally inferior canned or processed foods) (FGD 23, middle-aged women).

Far more striking, however, was the extent to which the explanations given by the respondents focused on the social and cultural causes of “bad” deaths, rather than biological or physical ones. Indeed, in the main, the FGDs were far less interested in, and preoccupied by, the immediate problems of bodily illness and the problems of treatment; death was understood and explained through an avowedly social lens – a “bad” death being first and foremost a symptom of a cultural and moral condition. Indeed, bodily illness was rendered as a symptom of a more fundamental social problem, and therefore explanations of death were similarly derived from accounts of the (social and moral) quality of life in the community.

For many of those who revel in the fecundity of life in the “new” South Africa, death is explained as a necessary price to be paid for the joys of freedom. As one young woman put it, “we have the freedom to be delinquent” (FGD 9, young women). Or, in the words of a young man:

We tell ourselves that if AIDS exists, then it means we will be infected, therefore we do not take precautions. We do as we wish. I practise sex like nobody’s business and I feel proud of myself…. I deliberately practise sex without using a condom and the result is that AIDS will spread like wildfire and once more it will kill me. (FGD 6, young men)

For others, more fearful of the disruptive effects of the social and political changes, there is resignation to death as an inevitable consequence of a society losing its way:

Gone is the past. When [our parents] tell us that something is taboo, we simply yawn and continue to live our own way; we do not want to live according to the way our parents lived in the past, so we find ourselves dying in large numbers because we lost our humanity. (FGD 5, young men)

A similar refrain echoed through the FGDs with older respondents:

People think they have freedom whereas the freedom they have is leading them to death. (FGD 26, older men)

We no longer respect the olden day’s rule, which is the reason for death to have increased, because we have lost our culture. (FGD 33, older women)

This erosion of cultural norms and “traditions” was understood to link directly to current patterns of death in several ways. Because the youth flouted the authority of their parents and wives no longer deferred to their husbands, the society had become more promiscuous. This surfeit of sex was in turn directly associated with the profusion of death – either because the respondents understood that the HI virus was sexually transmitted, or via the idea that people were dying from “traditional” diseases caused by the violation of cultural taboos on sex during mourning. The fact that cultural norms allegedly lacked their prior purchase was then invoked as a reason for the breach of these taboos, resulting in the death of those party to it.

The idea of cultural death, then, was the most frequently cited, and copiously discussed, reason given for the escalation of bodily deaths. Less prominent, but often mentioned nevertheless, was the practice of witchcraft. Some of the younger men seemed reluctant to engage directly in this conversation, alluding to the problem rather than grappling with it explicitly and fully. In one of the FGDs with young men, one respondent made the point, “there is witchcraft, black magic. This is another serious problem in our area.” One of the other group members responded, “you know there you are really talking, my brother”. A pause ensued. The facilitator tried to open up the issue more fully, but the conversation shifted (pilot FGD 1, young men).

References to witchcraft were more fulsome in the FGDs with middle-aged and older men:

There are evil people who bewitch young people because they envy them; should they notice that you are successful, they bewitch you, and that is the end.

If I can tell you the truth I can say that witchcraft is much in existence. (FGD 17, middle-aged men)

Uncertainties and contestations surrounding HIV/AIDS

As with the discussion of “bad death”, many respondents declared themselves mystified by the question of HIV/AIDS:

Really I do not know what causes it. (FGD 24, middle-aged women)

AIDS is difficult to understand. (FGD 30, older men)

The pervasive and virulent stigma attaching to AIDS in the area compounds the fear and mysteriousness surrounding the epidemic, by stifling opportunities for open public discussion on the subject. By the third in the series of FGDs, however, the large majority of group members were willing to volunteer their own understandings of what the illness was, how it spread, and what its effects were. Indeed, one of the most striking, if not unexpected, findings of the study was the multiplicity of versions of what HIV/AIDS is and what causes it. These ranged from the scientific orthodoxy on the subject, through versions of AIDS as a “traditional” sickness caused by the breach of customary taboos, conspiracy theories of AIDS as a plot by whites – particularly white doctors – to infect blacks, and the idea of AIDS as an effect of the witchcraft alleged to be rife in the area.

Given various efforts at public health education on community radio, in local schools, and in clinics in the area, along with programmes and messaging on national television, it is unsurprising that it was the younger respondents in the focus groups who were most likely to reproduce the version of HIV as a sexually transmitted virus that attacks the body’s immune system, eventually causing death. Less predictable, however, was the relative infrequency with which this version of HIV/AIDS was adduced. During the course of the 36 FGDs, only seven respondents volunteered this version of the illness and, of the seven, only one was not a member of the young focus groups. Moreover, even in these cases, the course of the conversations tended to cast doubt on the authority of this body of information in the everyday lives of those who could reproduce it. For example, at the outset of the AIDS FGD with one of the groups of young women, one respondent – the first to speak – was quick to recite the orthodoxy:

AIDS is a virus that lives in a human body; you can get infected from this virus through sexual intercourse; but this virus is called HIV. So when you sleep with a person who is HIV positive you can simply get infected. Moreover this virus causes AIDS. (FGD 12, young women)

Later on in the FGD, however, it became clear that she had doubts about the persuasiveness of this version of AIDS.

… this guy who is believed to be suffering from AIDS: his girlfriend died of AIDS but he still looks healthy…. Why is he not sick? This gives us doubts pertaining to AIDS; it confuses me. (FGD 12, young women)

The limited appeal of the scientific orthodoxy was also evident in the responses of two other members of this group, who came up with a more syncretic view, fusing the Western scientific understanding of AIDS as caused by a sexually transmitted virus, with indigenous notions of sexuality and sexual health linked to the transfer of bodily fluids:

When a person sleeps with many people, the fluids form a virus that causes AIDS, which troubles many people. The dirty fluids form illnesses…. A person who sleeps with different people should clean her private parts thoroughly because failure to do so may result into [sic] serious diseases including AIDS. (FGD 12, young women)

Many other versions of the disease were totally unconnected to the idea of a sexually transmitted virus (even if sexual transgressions were considered integral to a person’s propensity to get sick). In one of these alternative versions, a group of older women adduced a version of AIDS linked to the proliferation of worms in a woman’s body as the symptom and vector of contamination:

I just heard that AIDS is tiny worms that get into the human body and kill the affected person…. This thing was not there in the old days. It is a recent thing and it kills a lot of people. They say it is caused by sex but what surprises me is that sex has long been part of our parents’ and our grandparents’ lives, and AIDS was not there. (FGD 24, middle-aged women)

The FGDs also exposed a plethora of conspiracy theories of AIDS – not a surprising finding given the extent of scepticism, disbelief, and/or ignorance in respect of the current science of AIDS, and the ways in which these dispositions articulate with the anxieties provoked by political transition. One FGD with older men was particularly prolific in this vein:

Doctors work with funeral undertakers; the more people they infect with AIDS, the more money they get from funeral undertakers. (FGD 30, older men)

AIDS was brought by whites; they made condoms and contaminated them with AIDS. (FGD 30, older men)

Other versions of the disease located it, more inchoately, in the very fabric of everyday life, as a symptom of the contamination of the natural world:

We get AIDS from the tap water that we drink and from food; all these trees breathe out AIDS; our beds have AIDS, our pillows too; the air we breathe contains AIDS. (FGD 30, older men)

In the midst of this multiplicity of versions of HIV/AIDS, however, the most extended and animated discussions in the FGDs on AIDS focused on the relationship between AIDS and “traditional” diseases, with many respondents exchanging views about the extent to which AIDS was a new form of, or simply a renaming of, a familiar and long-standing traditional illness – tindzhaka in particular. For many of the respondents, young and old, AIDS was an anglicized version of what had long been known as tindzhaka – an illness caused by the breach of cultural taboos on sex during mourning. As one of the older women put it, “it is the disease of the past and they now changed the name to English and call it AIDS” (FGD 31, older women).

While the issue of tindzhaka was raised repeatedly during the FGDs, it was difficult to glean one consistent version of its symptoms and effects. A series of key informant interviews were therefore conducted with traditional healers, in pursuit of a deeper understanding of this illness. Yet the accounts yielded by these interviews were themselves plural. Whereas all the healers interviewed agreed that tindzhaka was curable and AIDS was not, their versions of tindzhaka varied. For example, one account tied the illness very closely to a sexual breach following a death in the family:

Tindzhaka is a result of breaking the rule when there is death in a family. Like now a woman might have given birth to a first, second, third, fourth, and fifth son. In order to prevent tindzhaka the last born needs to be the first one to begin [to have sex]. It is Saturday and we are through with the funeral. We call all our children, “listen very well my children, now the funeral is over, so tonight you should sleep with your wives, the youngest one should begin followed by the second youngest, you should proceed in that order until the first born”. The parents should be the last to perform sex. The one wearing the mourning clothes should abstain until the cleansing period. (Interview with female Inyanga)

Another account was more elastic, locating the origins of the illness in the conjunction of taboos on eating and sex in the aftermath of a family death:

According to me tindzhaka is a disease that affects people who disrespect family or tradition laws. For instance, if my father-in-law passes away, I should not eat food at his funeral and come back and sleep with my wife. I should at least abstain from having sex with her until after five days; after that period the food I ate there will no longer be in my body. (Interview with male Inyanga)

A more extended analysis of the variations and nuances within different versions of tindzhaka, and its relationship to AIDS, is beyond the scope of this paper. Rather, it is exactly the imprecision and uncertainties associated with people’s understandings of tindzhaka, as well as its articulation with HIV/AIDS, that are significant here, as markers of both the haziness and the plasticity that attach to popular understandings of the epidemic.

Discussion

The findings presented in this paper and their relationship to relevant literature are not exhaustive; space constraints have necessitated the omission, inter alia, of findings on sexual risk-taking, the origins and effects of AIDS stigma, and the responses to various treatment options. This limits the scope of the discussion we can present here. Still, there are several noteworthy features of the data we have assembled.

In the midst of high levels of stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS, at both national and local levels, AIDS and AIDS-related deaths are not comfortable subjects of public conversation. So, unsurprisingly, it typically took some time for the members of the various FGDs to engage with the nature and effects of the illness. By the end of each series of focus groups, however, the FGDs had succeeded in enabling a reasonably expansive discussion of death and AIDS in Agincourt. Moreover, in each focus group, there was a consensus that the illness (whether or not it was called AIDS, and whether or not it was deemed wholly new or an old disease by another name) was rife in the area, and constituted a major social, familial, and personal problem, in Agincourt and in South Africa more widely.

Some versions of the illness disconnected it from sex and sexual transmission (such as explanations referring to the quality of food, water, air, contamination by doctors, etc.) but, in the main, people’s perceptions recognized a link with sex. Even in versions of AIDS that merged or aligned it with tindzhaka, a sexual transgression was at the heart of the problem – alongside the perception that dangerous or bad sex was both a vector and a symptom of social and cultural disorder. Yet, if there is agreement on the centrality of sex in relation to AIDS, the meanings attached to sex and the various versions of its relationship to the illness are deeply embedded in local cosmologies and belief systems.

Indeed, the most significant finding of this study is arguably the power of cultural “tradition” in popular versions of the “bad death” that has beset the Agincourt area in recent years. Questionnaires filled in by the focus-group members established that many were regular churchgoers, or members of church groups. Yet the idea of God’s vengeance for moral transgression was seldom mentioned as an explanation for the escalating death rate – even in the case of respondents who made references to a divine power in their accounts of life and death. Rather, the emphasis fell overwhelmingly on the ways in which cultural lapses – the death of “traditions” – have caused new patterns of biological death. This demonstrates, in turn, one of the principal conclusions of this research, namely that in order to appreciate popular understandings of AIDS-related deaths in the Agincourt area, it is critically important to recognize the close relationship between the health of the social body and the health of the individual body, within the local worldview. One of the recurring themes in all the FGDs, irrespective of age and gender, was the repeated contention that (physical) illness multiplies in a society that has become (culturally) ill.

In the case of HIV/AIDS, the physical illness is read as a symptom of the cultural damage inflicted by the country’s transition to democracy – principally through the allocation of new-found rights and freedoms to women and children that are seen as flouting patriarchal “traditions”, and undermining the corner-stones of moral order in the community. In ways which mythologize and romanticize the history of apartheid, the FGDs cumulatively created a narrative of the country’s past and present, with 1994 as a critical moment of rupture, in which the “traditional” stability in gender and generational relations was rudely subverted by the experience of “freedom”.

These conclusions have a number of salient implications for the practice of public health, and the allied research efforts to contain the spread of the AIDS epidemic.

The research findings underline the distinction between a person’s ability to reproduce information about AIDS that derives from the scientific orthodoxy on the subject, and the beliefs that guide his or her thinking and action. Information can be recited by rote, without necessarily being internalized as the basis on which to interpret experiences and make choices. The FGDs demonstrated the extent to which the receipt of public health information can coexist alongside a series of incommensurate beliefs concerning the conditions of health, the causes of disease, and the nature of AIDS in particular. This finding, therefore, should caution against public health interventions that deduce the success of a prevention message from respondents’ abilities to recite the scientific orthodoxy concerning AIDS – without exploring further the extent to which this view has been internalized as the basis of choice and action.

Showing that our respondents’ explanations of HIV/AIDS defy conventional public health explanations also has significant implications for ongoing prevention and intervention initiatives. Chopra & Ford suggest that public health challenges such as HIV/AIDS require strategies that better engage families and communities in preventing disease [22]. They argue for the need to move away from the traditional model, which increases resources, “to a centralized bureaucracy that tries to increase the supply of services including health promotion messages”. The findings we present here underscore recent conclusions in the health-promotion literature to reject “generalized models of how people or villages should behave” [22].

But our findings also highlight the need to understand cultural explanations in terms of representations of AIDS treatment, particularly medication. Cultural background and its effects on beliefs concerning medication is part of a growing body of research on culture and the management of chronic conditions including HIV/AIDS [24,25]. Our findings reveal that in this community Western medicine (and potentially anti-retroviral therapy) is viewed by some with fear and scepticism. AIDS presents health professionals with a growing challenge to establish therapeutic partnerships with patients (and their families). Recent studies on medicine-taking behaviour suggest that patient/family-centred therapeutic regimes that incorporate social and cultural understandings of illness and treatment are effective in the management of chronic conditions [25-27].

Finally, this study underscores that local and provincial health services need to be cognizant of how the views expressed of doctors conspiring to transmit the HI virus directly to patients probably reflect a more general mistrust and suspicion of health workers and the health services. Efforts to dispel mistrust are required, as health services move towards improving the uptake of voluntary counselling and testing, and gear up for a more accessible roll-out of antiretroviral therapy. It is hoped that effective management and therapeutic partnerships will draw many into treatment. However, the relationship between availability of effective treatment and community beliefs is, at this point, fluid and unpredictable.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Andrew Mellon Foundation, USA. Ethical clearance is from the University of the Witwatersrand’s Committee on Human Subjects (Medical). The authors thank the MRC/Wits-Agincourt management team for their support of this project.

Footnotes

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed according to the usual Scand J Public Health practice and accepted as an original article.

References

- [1].Posel D. Sex, death and the fate of the nation: reflections on the politicisation of sexuality in post-apartheid South Africa. Africa. 2005;75:125–53. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Schneider H. On the fault-line: The politics of AIDS policy in contemporary South Africa. African Studies. 2002;61:145–68. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Collinson MA, Lurie M, Kahn K, Wolff B, Johnson A, Tollman SM. Health consequences of migration: evidence from South Africa’s rural north-east (Agincourt) In: Tienda M, Findley S, Tollman SM, Preston-Whyte E, editors. Africa on the move: Migration and urbanisation in comparative perspective. Witwatersrand University Press; Johannesburg: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tollman SM, Herbst K, Garenne M, Gear JSS, Kahn K. The Agincourt Demographic and Health Study: Site description, baseline findings and implications. S Afr Med J. 1999;89:858–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kahn K, Garenne ML, Collinson MA, Tollman SM. Mortality trends in a new South Africa: Hard to make a fresh start. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35(Suppl 69):26–34. doi: 10.1080/14034950701355668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Department of Health . Summary report: National HIV and Syphilis Antenatal Seroprevalence Survey in South Africa 2003. Directorate Health Systems Research, Research Coordination and Epidemiology, Department of Health; Pretoria: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lewando-Hundt G, Stuttaford M, Ngoma B. The social diagnostics of stroke-like symptoms: healers, doctors and prophets in Agincourt, Limpopo Province, South Africa. J Biosoc Sci. 2004;36:433–43. doi: 10.1017/s0021932004006662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wilson D, Lavelle S. AIDS prevention in South Africa: A perspective from other African countries. S Afr Med J. 1993;83:668–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Abdool-Karim Q, Sraim S, Soldan K, Zondi M. Reducing the risk of HIV infection amongst South African sex workers. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1521–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.11.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Peterson I, Swartz L. Primary Health Care in the era of HIV/AIDS: Some implications for health systems reform. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:1005–13. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Walker L, Reid G, Cornell M. Waiting to Happen: HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Double Storey/Juta; Cape Town: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Heald S. It’s never as easy as ABC: Understandings of AIDS in Botswana. Afr J AIDS Res. 2002;1:1–10. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2002.9626539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wolf A. AIDS or Kanyera? Concepts of sexuality and the discourse on morality in Malawi. Paper presented at the AIDS in Context Conference; 4–7 April; Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Campbell C. Selling sex in a time of AIDS: The psychosocial context of condom use by sex workers on a southern African mine. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:479–94. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Leclerc-Madlala S. Virginity testing: Managing sexuality in a maturing HIV/AIDS epidemic. Med Anthropol Q. 2001;15:533–52. doi: 10.1525/maq.2001.15.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].MacPhail C, Campbell C. “I think condoms are good but, aai, I hate those things”: Condom use among adolescents and young people in a southern African township. Soc Sci Med. 2001;51:1613–27. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gilbert L, Walker L. Treading the path of least resistance: HIV/AIDS and social inequalities – a South African case study. Soc Sci Med. 2001;54:1093–1110. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Campbell C, MacPhail C. Peer education, gender and the development of critical consciousness: Participatory HIV prevention by South African youth. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:331–45. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gregson S, Terceira N, Mushati P, Nyamukapa C, Campbell C. Community group participation: Can it help young women to avoid HIV? An exploratory study of social capital and school education in rural Zimbabwe. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:2119–32. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Morisky DE, Ang A, Coly A, Tiglao TV. A model HIV/AIDS risk reduction programme in the Phillipines: A comprehensive community-based approach through participatory action research. Health Promotion Int. 2004;19:69–76. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Berer M. HIV/AIDS, sexual & reproductive health: Intersections and implications for national programmes. Health, Policy & Planning. 2004;19:62–70. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chopra M, Ford N. Scaling up health promotion interventions in the era of HIV/AIDS: challenges for a rights based approach. Health Promotion Int. 2005;20:383–90. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dai018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Marais H. Buckling. The impact of AIDS in South Africa. University of Pretoria; Pretoria: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Horne R, Graupner L, Frost S, Weinman J, Wright SM, Hamkins M. Medicine in a multi-cultural society: The effect of cultural background on beliefs about medications. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:1307–13. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bissell P, May CR, Noyce PR. From compliance to concordance: Barriers to accomplishing a re-framed model of health care interactions. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:851–62. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Power R, Koopman C, Volk J, Israelski DM, Stone L, Chesney MA, Spiegal D. Social support, substance use, and denial in relationship to antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected persons. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2003;17:245–52. doi: 10.1089/108729103321655890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].McCoy D, Chopra M, Loewenson R, Aitken JM, Ngulube T, Muula A, et al. Expanding access to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: Avoiding the pitfalls and dangers, capitalising on opportunities. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:18–22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.040121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]