Abstract

A chelator fragment library based on a variety of metal binding groups was screened against a metalloproteinase. Lead hits were identified and an expanded library of select compounds was synthesized, resulting in numerous high-affinity hits against several metalloprotein targets. The findings clearly demonstrate that chelators can be used to generate libraries suitable for fragment-based lead design (FBLD) directed at important metalloproteins.

Keywords: chelators, fragment-based lead design, libraries, metalloproteins, zinc

Fragment-based lead design (FBLD), sometimes referred to as fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD), is an increasingly important strategy for the discovery of biologically active compounds.[1] FBLD generally uses libraries consisting of modest collections (100–1000 compounds) of small molecular fragments (MW <300 amu) that are screened against targets of interest.[2] Although such fragments do not bind as tightly (Kd values in the micro- to milli-molar range) as more complex molecules, including those used in high-throughput screening (HTS) approaches, they can provide ‘hits’ that serve as efficient starting structures for the development of potent inhibitors. Fragments that bind to a target are identified, after which one of two approaches is generally pursued: a) a single fragment can be elaborated in order to obtain a tight binder; or b) multiple fragments binding at adjacent and distinct sites can be connected by an appropriate linker to obtain a potent inhibitor. Compared to HTS, FBLD is purported to have several advantages, including a more efficient exploration of chemically diverse space and higher ligand efficiencies.

Although the application of FBLD to metalloprotein targets of medicinal interest has been described,[3] the design, synthesis, and use of general fragment libraries based on metal chelators for FBLD applications has not been widely reported.[4–7] This is surprising in light of the fact that several small-molecule chelators have been shown to effectively inhibit metalloproteins.[8, 9] Furthermore, FBLD using metal-chelating moieties should be particularly well suited for inhibitor discovery against metalloproteins because: a) chelators demonstrate binding affinities suitable for FBLD screening; b) chelators provide a diverse range of molecular platforms from which to develop lead compounds; and c) the propensity for chelators to bind metal ions allows for better prediction of their probable binding position within a protein active site in the absence of experimental structural data of the complex. Herein, we describe the preparation of an expanded chelator fragment library (eCFL) derived from a chelator fragment library (CFL), showing the usefulness of these libraries in identifying novel leads for metalloprotein inhibitors, including inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and anthrax lethal factor (LF).[10]

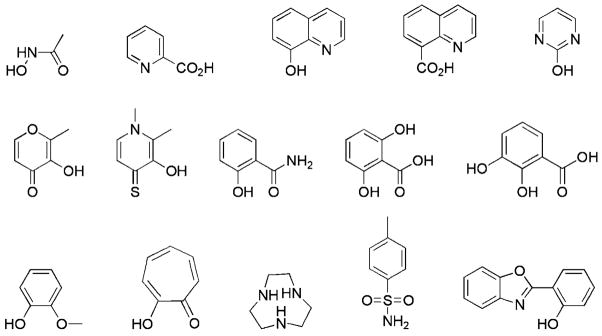

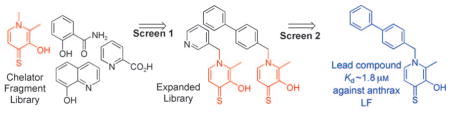

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) represent one of the most well-established targets in the realm of metalloproteins. These zinc(II)-dependent enzymes have been extensively studied, and the development of MMP inhibitors (MMPi) has played an important role in the discovery of inhibitors for other zinc(II)-dependent metalloproteins, such as anthrax lethal factor (LF), histone deacetylases (HDACs), and others.[10] Indeed, the earliest application of FBLD to a metalloprotein target was directed at MMP-3.[3] Therefore, we focused our preliminary library screening efforts on MMPs, as a representative system for identifying fragments that would bind zinc(II) metalloproteins. Based on widely-reported criteria for fragment libraries,[2] an initial chelator fragment library (CFL-1) was assembled. A modest library containing 96 structural cores was prepared from chelators with two to four donor atoms for binding metal ions and sufficient solubility for screening (Figure 1). The chelating groups included picolinic acids, hydroxyquinolones, pyrimidines, hydroxypyrones, hydroxypyridinones and salicylic acids, in addition to other compounds that are well-established components of metalloprotein inhibitors, such as hydroxamic acids and sulfonamides (Figure 1). The CFL-1 library was screened against MMP-2, at a fragment concentration of 1 mM, using a fluorescent based assay (see Supporting Information).[11] From the library, 31 compounds were found to be weak “hits” (>50 % inhibition); this high hit rate is consistent with the fact that all fragments are known metal chelators. Several of the hits were known from previous studies,[8, 9] thus validating the screening approach as positive controls. Importantly, several fragments identified have not been widely reported for use in metalloprotein inhibitors (figure S2, Supporting Information).

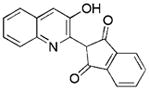

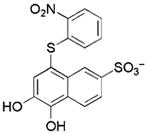

Figure 1.

Representative compounds from chelator fragment library 1 (CFL-1). For the full list of compounds, see the Supporting Information (figure S1).

Preliminary screening results obtained from CFL-1 prompted the development of an eCFL-1 geared toward the inhibition of specific zinc(II) metalloproteins. The components of eCFL-1 were based on one of the chelator hits (3-hydroxy-1,2-dimethylpyridine-4(1H)-thione) from CFL-1 against MMP-2. The expanded library was used to demonstrate that hits from the parent library (CFL-1) could be further elaborated to more advanced leads, just as in a traditional hit maturation approach. Derivatives of 3-hydroxy-1,2-dimethylpyridine-4(1H)-thione (3,4-HOPTO), which consists of an O,S atom donor set, and its O,O analogue 3-hydroxy-1,2-dimethylpyridine-4(1H)-one (3,4-HOPO), were used for the generation of eCFL-1 (figure S3, Supporting Information).

In order to prepare a reasonable number of 3,4-HOPO and 3,4-HOPTO derivatives, a robust microwave-assisted synthetic procedure was developed (scheme S1, Supporting Information).[12] Using reaction conditions adapted from Orvig et al.,[13] ~2.2 equiv of amine and 1 equiv of hydroxypyrone (or hydroxypyrothione) heterocycle were combined in HCl and irradiated in a microwave synthesizer, generating the desired products in <2 min. These conditions were used to produce 63 3,4-HOPO fragments and 24 3,4-HOPTO fragments. Isolated yields for these reactions ranged between 3–50 %. The 3,4-HOPO fragments outnumber those obtained for 3,4-HOPTO owing to their ease of isolation, as the 3,4-HOPO fragments generally precipitated from the reaction mixture upon cooling. In contrast, the 3,4-HOPTO reactions resulted in mixtures (as shown by TLC) and in most cases required flash silica column chromatography to isolate (see Experimental Section for details). Nevertheless, the resulting small fragment library (87 components) was suitable for screening in a 96-well plate format (see Supporting Information). The fragments in eCFL-1 possessed chemical properties that are consistent with reported FBLD libraries (MW between 139 and 353 amu with only 8 fragments >300 amu; number of H-bond donors and acceptors between 0 and 2).[2]

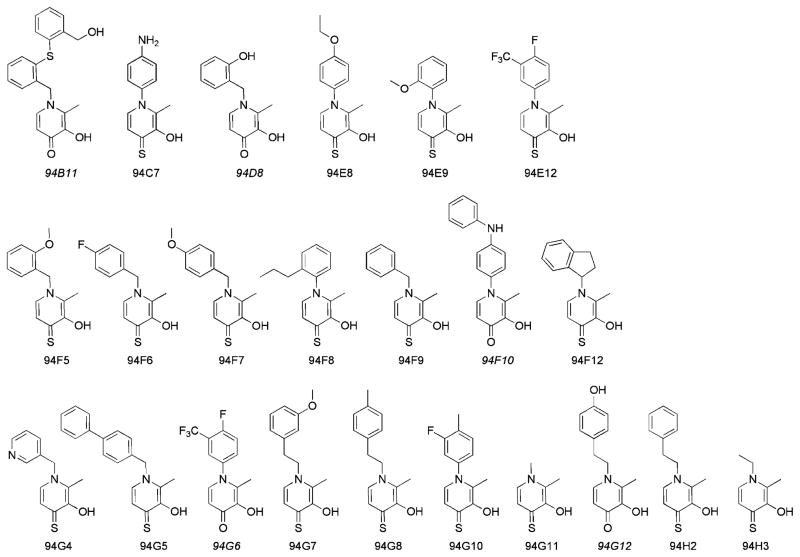

The eCFL-1 library was screened, using commercially-available fluorescence-based assays, against four zinc(II)-dependent metalloprotein targets: gelatinase-1 (MMP-2), gelatinase-2 (MMP-9), stromelysin-1 (MMP-3), and anthrax lethal factor (LF). All fragments were tested at a concentration of 50 μM; compounds that showed >50 % inhibition of metalloenzyme activity were classified as a hit against that enzyme (Figure 2). Dose response IC50 values for the resulting hits were then determined (Table 1).

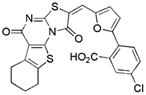

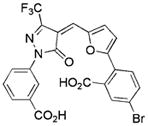

Figure 2.

Lead hits identified against zinc(II)-dependent metalloenzymes from a expanded library (eCFL-1) of 3,4-HOPO and 3,4-HOPTO fragments. 3,4-HOPO fragments are noted in italics.

Table 1.

IC50 values of lead fragments against metalloenzyme targets.a

| Compd | IC50b [μM] | Ligand Efficiencyc [kcalmol −1] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF | MMP-2 | MMP-3 | MMP-9 | ||

| 94B11 | 34 | × | × | × | – |

| 94C7 | × | 34 | × | × | – |

| 94D8 | 17 | × | × | × | – |

| 94E8 | × | 13 | 33 | 17 | 0.46 |

| 94E9 | 41 | × | × | × | – |

| 94E12 | 34 | 33 | × | 33 | 0.33 |

| 94F5 | × | 20 | × | 21 | 0.38 |

| 94F6 | × | 12 | 28 | 12 | 0.42 |

| 94F7 | × | 10 | 39 | 9 | 0.41 |

| 94F8 | 13 | 24 | × | 20 | 0.38 |

| 94F9 | × | 23 | × | 21 | 0.43 |

| 94F10 | 23 | × | × | × | – |

| 94F12 | 32 | 4 | × | 8 | 0.41 |

| 94G4 | × | 34 | × | 23 | 0.42 |

| 94G5 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0.37 |

| 94G6 | × | × | × | 36 | 0.33 |

| 94G7 | × | 17 | × | 18 | 0.37 |

| 94G8 | 38 | 30 | 38 | 19 | 0.38 |

| 94G10 | 21 | 35 | × | 31 | 0.39 |

| 94G11 | × | 35 | × | 41 | 0.65 |

| 94G12 | × | 29 | × | 30 | 0.37 |

| 94H2 | × | × | × | 30 | 0.39 |

| 94H3 | × | 36 | × | 34 | 0.60 |

IC50 values of > 50 μM are designated with an ×. Standard deviations from triplicate measurements for all values listed are <10 %. Ligand efficiencies for some fragments are also provided.

Gelatinase-1 (MMP-2), gelatinase-2 (MMP-9), stromelysin-1 (MMP-3), and anthrax lethal factor (LF).

Calculated for fragments against MMP-9.

The 87-fragment library generated a total of 17 hits against MMP-2, 18 hits against MMP-9, 5 hits against MMP-3, and 10 hits against LF (Table 1). Considering the overall modest number of compounds screened (87 in eCFL-1), this result is quite remarkable. Hits with similar affinities have generally been obtained with much greater effort by testing libraries consisting of >10 000 compounds in HTS campaigns.[14, 15] Between the two different fragment groups in eCFL-1, the 63 3,4-HOPO fragments produced only one hit against MMP-2 (94G12), two hits against MMP-9 (94G6, 94G12) and three hits against LF (94B11, 94D8, 94F10). There were no 3,4-HOPO hits identified against MMP-3. Of the 24 3,4-HOPTO fragments screened, 16 hits were found against MMP-2, 16 hits against MMP-9, 5 hits against MMP-3, and 7 hits against LF. The significant difference in the number of hits generated from the smaller 3,4-HOPTO set of fragments against these metalloenzymes highlights the importance the chelating group plays in these libraries. The O,S-chelator of the 3,4-HOPTO fragments produced at least five or more hits against each enzyme, despite being the smaller subset (~28 %) of eCFL-1.

With only one exception (94C7), all of the hits against MMP-2 were also found to be hits against the other gelatinase, MMP-9. The identification of common hits for MMP-2 and MMP-9 is consistent with the high degree of structural homology between the catalytic domains of these enzymes. A review of the literature shows that most MMP-9 inhibitors are also potent against MMP-2, but the reverse is not necessarily true due to the slightly larger S1′ pocket present in MMP-2.[16] Only five fragments, all based on the 3,4-HOPTO chelator, were shared hits across the three MMPs. Among these, only one 3,4-HOPTO fragment (94G5) was a hit against all four metalloenzymes tested. Four fragments were found to only be hits against LF (94B11, 94D8, 94E9, 94F10).

The most potent fragment identified against all the metalloenzymes was 94G5, which is comprised of a 3,4-HOPTO chelator and a biphenyl moiety. This fragment showed a particularly notable IC50 value of 3 μM against anthrax LF. Although a handful of very potent (<0.5 μM) LF inhibitors have been reported,[17] the activity of the 94G5 fragment against LF rivals many of the described inhibitors.[4,14, 15,18–21] Interestingly, the biphenyl substituent found in 94G5 is common to other LF[18, 22] and MMP inhibitors,[3, 23] although it is quite possible that the biphenyl group in 94G5 does not occupy the same subsite as this moiety in these previously reported inhibitors. Nonetheless, this finding validates the ability of the chelator fragment library approach to identify potent structures that are consistent with established chemical motifs for these metalloprotein targets.

The development of effective inhibitors of LF has proven to be particularly difficult.[24] Comparing the results obtained here against LF with those obtained from traditional HTS approaches further highlights the significance of these chelator fragment libraries. Table 2 compares the five most potent LF hits obtained from eCFL-1 to the top hits obtained from two previously reported HTS screens performed on libraries that each contained at least 10 000 compounds.[14, 15] These results show that eCFL-1, with only 87 components, generated hits that are comparable or superior in potency, ligand efficiency and drug-likeness to those obtained from labor- and cost-intensive HTS screens. Specifically, compared to the typical HTS campaigns reported, the proposed FBLD approach provided: 1) a much higher hit frequency (11 % for eCFL-1 versus <0.25 % for the HTS libraries), 2) ligand efficiencies[25] equal to or higher than those observed for the HTS hits; and 3) compounds that are generally more drug-like given their initial selection based on general drug-like criteria. In fact, the low-molecular weight of the fragments identified in eCFL-1 are still amenable to further elaboration (<307 amu), unlike most of the HTS hits,[14, 15] which are already near the conventional MW limits for a small-molecule therapeutic (Table 2).[26] Overall, this comparison shows that chelator-based fragment libraries are a much more efficient and effective way to explore the relevant chemical space for metalloprotein targets.

Table 2.

Comparison of leads identified for anthrax LF by chelator-based FBLD (this work) versus large library (≥ 10 000 compounds) HTS findings.

| Compda | IC50/Ki [μM]b | MW [amu] | ΔG [kcal mol−1] | Ligand Efficiency [kcal mol−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 94D8 | 17/4.3 | 231 | −7.4 | 0.43 |

| 94F8 | 13/3.3 | 259 | −7.5 | 0.42 |

| 94F10 | 23/5.9 | 292 | −7.2 | 0.33 |

| 94G5 | 3/0.8 | 307 | −8.4 | 0.38 |

| 94G10 | 21/5.4 | 249 | −7.2 | 0.42 |

|

1.7/0.6 | 218 | −8.6 | 0.53 |

|

3.9/3.8 | 289 | −7.4 | 0.34 |

|

5.9/2.1 | 392 | −7.8 | 0.30 |

|

0.8/0.8 | 510 | −8.4 | 0.25 |

|

1.7/1.6 | 549 | −7.9 | 0.23 |

Compounds identified in this study shown by alphanumeric code, compounds identified in reference HTS studies shown by structure

See Supporting Information for the determination of Ki values.

In summary, we have presented a new approach to fragment libraries based on known small-molecule chelators and derivatives of these metal-binding molecules. The chelator fragment library (CFL-1) produced several hits when screened against a matrix metalloproteinase. Two chelators from this library were used to prepare a modest expanded library of hydroxypyridinone and hydroxypyridinethione fragments that were screened against four zinc(II)-dependent metalloprotein targets. This screen revealed a high hit rate for hydroxypyridinethione fragments and generated leads with good activity against all the metalloenzymes, including anthrax LF. The results obtained show that these chelator libraries are particularly well suited for the application of FBLD against metalloprotein targets. Indeed, our findings demonstrate that this approach produces, with a relatively modest screening effort, high-quality hits that are superior to those obtained from traditional HTS campaigns where random libraries of tens of thousands of compounds are tested. These findings clearly demonstrate the potential of chelator-based libraries for targeting metalloproteins. Such libraries should be useful for identifying lead structures against a variety of metalloenzymes, well beyond the zinc(II)-dependent targets reported here. Efforts along these lines are underway and will be reported in due course.

Experimental Section

General synthetic procedure for eCFL-1

3,4-HOPO derivatives

A solution of 3-hydroxy-2-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one (maltol; 200 mg, 1.58 mmol) in HCl (0.38 M, 2 mL) in a 10 mL microwave reaction vessel was treated with amine (3.5 mmol, 2.2 equiv). The heterogenous reaction mixture was sealed and stirred at 65 °C for 5 min prior to one microwave cycle of 1.5 min at 165 °C, 250 psi (maxP), and 300 W. The product was precipitated from solution at 4 °C overnight, isolated by vacuum filtration, and dried in vacuo.

3,4-HOPTO derivatives

A solution of 3-hydroxy-2-methyl-4H-pyran-4-thione (thiomaltol; 200 mg, 1.41 mmol) in HCl (0.38 M, 2 mL) in a 10 mL microwave reaction vessel was treated with amine (3.1 mmol, 2.2 equiv). The heterogenous reaction mixture was sealed and stirred at 65 °C for 5 min prior to one microwave cycle of 1.5 min at 165 °C, 250 psi (max P), and 300 W. The reaction typically produced a yellow solution with a black, oily residue at the bottom of the tube. The reaction mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2×) and the organic phase was dried (MgSO4), vacuum filtered and evaporated in vacuo to give a dark residue. Purification by silica column chromatography (CH2Cl2 or 0–2 % MeOH in CH2Cl2) gave the desired product.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yongxuan Su (U.C.S.D.) for assistance with mass spectrometry measurements. This work was supported by the University of California, San Diego and the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL080049–04 and R03 AI070651–02 to S.M.C; R01 AI059572 and U01 AI070494 to M.P.).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cmdc.200900516.

Contributor Information

Maurizio Pellecchia, Email: mpellecchia@burnham.org.

Seth M. Cohen, Email: scohen@ucsd.edu.

References

- 1.Hajduk PJ. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6972. doi: 10.1021/jm060511h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Congreve M, Chessari G, Tisi D, Woodhead AJ. J Med Chem. 2008;51:3661. doi: 10.1021/jm8000373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olejniczak ET, Hajduk PJ, Marcotte PA, Nettesheim DG, Meadows RP, Edalji R, Holzman TF, Fesik SW. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:5828. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel V, Mazitschek R, Coleman B, Nguyen C, Urgaonkar S, Cortese J, Barker RH, Jr, Greenberg E, Tang W, Bradner JE, Schreiber SL, Duraisingh MT, Wirth DF, Clardy J. J Med Chem. 2009;52:2185. doi: 10.1021/jm801654y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sternson SM, Wong JC, Grozinger CM, Schreiber SL. Org Lett. 2001;3:4239. doi: 10.1021/ol016915f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flipo M, Beghyn T, Charton J, Leroux VA, Deprez BP, Deprez-Poulain RF. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:63. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salvino JM, Mathew R, Kiesow T, Narensingh R, Mason HJ, Dodd A, Groneberg R, Burns CJ, McGeehan G, Kline J, Orton E, Tang SY, Morrisette M, Labaudininiere R. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:1637. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobsen FE, Lewis JA, Cohen SM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3156. doi: 10.1021/ja057957s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puerta DT, Lewis JA, Cohen SM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8388. doi: 10.1021/ja0485513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobsen FE, Lewis JA, Cohen SM. ChemMedChem. 2007;2:152. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puerta DT, Griffin MO, Lewis JA, Romero-Perez D, Garcia R, Villarreal FJ, Cohen SM. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2006;11:131. doi: 10.1007/s00775-005-0053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cablewski T, Faux AF, Strauss CR. J Org Chem. 1994;59:3408. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z, Rettig SJ, Orvig C. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:509. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson SL, Chen LH, Pellecchia M. Bioorg Chem. 2007;35:306. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schepetkin IA, Khlebnikov AI, Kirpotina LN, Quinn MT. J Med Chem. 2006;49:5232. doi: 10.1021/jm0605132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sang QXA, Jin Y, Newcomer RG, Monroe SC, Fang X, Hurst DR, Lee S, Cao Q, Schwartz MA. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:289. doi: 10.2174/156802606776287045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forino M, Johnson S, Wong TY, Rozanov DV, Savinov AY, Li W, Fattorusso R, Becattini B, Orry AJ, Jung D, Abagyan RA, Smith JW, Alibek K, Liddington RC, Strongin AY, Pellecchia M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502733102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agrawal A, de Oliveira CAF, Cheng Y, Jacobsen JA, McCammon JA, Cohen SM. J Med Chem. 2009;52:1063. doi: 10.1021/jm8013212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson SL, Jung D, Forino M, Chen Y, Satterthwait A, Rozanov DV, Strongin AY, Pellecchia M. J Med Chem. 2006;49:27. doi: 10.1021/jm050892j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Numa MMD, Lee LV, Hsu CC, Bower KE, Wong CH. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:1002. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panchal RG, Hermone AR, Nguyen TL, Wong TY, Schwarzenbacher R, Schmidt J, Lane D, McGrath C, Turk BE, Burnett J, Aman MJ, Little S, Sausville EA, Zaharevitz DW, Cantley LC, Liddington RC, Gussio R, Bavari S. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:67. doi: 10.1038/nsmb711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis JA, Mongan J, McCammon JA, Cohen SM. ChemMedChem. 2006;1:694. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agrawal A, Romero-Perez D, Jacobsen JA, Villarreal FJ, Cohen SM. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:812. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200700290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson SL, Pellecchia M. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:317. doi: 10.2174/156802606776287072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hopkins AL, Groom CR, Alex A. Drug Discovery Today. 2004;9:430. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipinski CA. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2000;44:235. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(00)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.