Abstract

First identified as a powerful vasoconstrictor, endothelin has an extremely diverse set of actions that influence homeostatic mechanisms throughout the body. Two receptor subtypes, ETA and ETB, which usually have opposing actions, mediate the actions of endothelin. ETA receptors function to promote vasoconstriction, growth, and inflammation while ETB receptors produce vasodilation, increases in sodium excretion, and inhibit growth and inflammation. Potent and selective receptor antagonists have been developed and have shown promising results in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases such as pulmonary arterial hypertension, acute and chronic heart failure, hypertension, renal failure and atherosclerosis. However, results are often contradictory and complicated because of the tissue-specific vasoconstrictor actions of ETB receptors and the fact that endothelin is an autocrine and paracrine factor whose activity is difficult to measure in vivo. Considerable questions remain regarding whether ETA selective or non-selective ETA/ETB receptor antagonists would be useful in a range of clinical settings.

Keywords: receptor localization, pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, chronic kidney disease

Shortly after it was discovered that the vascular endothelium releases a peptide capable of profound vasoconstriction, a considerable amount of attention was paid to the potential actions of endothelin in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. We have since learned a great deal about how this paracrine factor influences function in an extremely wide range of areas including neurotransmission, cell growth and epithelial transport, just to name a few. This myriad of activities has allowed the endothelin system to garner a tremendous amount of attention from the pharmaceutical industry with the development of numerous receptor specific and non-specific antagonists as well as efforts to identify drugs that inhibit endothelin synthesis. This work has led to new therapeutic approaches to pulmonary arterial hypertension and most likely other diseases in the not too distant future. In addition to this enormous drug discovery effort, it has also become clear that endothelin plays an important physiological role in maintaining blood pressure homeostasis, for example, by facilitating the excretion of a high salt diet. Because of the almost bewildering range of actions of the endothelin peptides, we limit this review to focus on the receptor-specific cardiovascular actions of endothelin.

ENDOTHELIN PEPTIDES

Endothelin-1, a 21-amino-acid long peptide first isolated from the supernatant of cultured endothelial cells, is perhaps the most potent vasoconstrictor substance known (1). The human endothelin family contains three 21-amino-acid long isopeptides, endothelin-1, endothelin-2 and endothelin-3 (ET-1, ET-2 and ET-3), which are each encoded by a separate, unique gene (2). The most extensively studied isopeptide, ET-1, is the major isopeptide of importance in the cardiovascular system (3, 4). Endothelial cells are a major source of ET-1, making this peptide fairly ubiquitous, and constitutive release of the peptide from the endothelium may contribute to basal vascular tone. ET-1 is also produced by a variety of other cell types including the inner medullary collecting duct and most other nephron segments, neurons of the central nervous system, postganglionic sympathetic neurons, and monocytes/macrophages. Under pro-inflammatory conditions, vascular smooth muscle cells and pulmonary epithelial cells can also produce ET-1. ET-2 and its mouse or rat analog vasoactive intestinal contractor appear to be predominantly expressed in the intestine, colon, ovary and uterus, but expression has also been reported in brain and kidney. High concentrations of ET-3 have been measured in rat brain, pituitary, lung and intestinal homogenates. ET-3 is also produced by monocytes/macrophages and by renal tubular cells, although in much smaller quantities than ET-1. The human heart reportedly expresses all three endothelin isoforms.

The mature endothelin peptides are formed following a series of proteolytic cleavages of their approximately 200-amino-acid long precursor peptides (5). Pre-pro-endothelins are converted within the cell firstly to the inactive pro-endothelin peptide after removal of the signal peptide, and then into 38–41 amino acid long “big endothelins”, a step catalyzed by furin in the case of ET-1. The big endothelins then undergo final conversion to the active form of the peptide by endothelin-converting enzyme (ECE). The two major ECE isoforms are ECE-1 and ECE-2, which are membrane-bound zinc metalloproteases that show 59% amino acid sequence homology and cleave big ET-1 with much greater efficiency than either big ET-2 or big ET-3. In addition, a big ET-3-selective enzyme, ECE-3, has been purified from bovine iris microsomes. There are several sub-isoforms of both ECE-1 and ECE-2, with these sub-isoforms differing in sub-cellular localization, allowing the conversion of big endothelins to mature endothelins to take place both on the cell surface and intracellularly, allowing secretion of mature endothelins from endothelial and possibly other cells (reviewed by (6) and (5)).

ENDOTHELIN RECEPTORS

The existence of multiple endothelin receptor subtypes was first hinted at by the characteristic biphasic blood pressure response to ET-1 in rats (1) and the differing pressor profiles of the three endothelin isoforms (2). In 1990, cloned cDNA sequences of two receptors for endothelin were published (7, 8). When cells were transfected with the cloned cDNA, 125I-labelled ET-1 was displaced from one receptor by all three peptides with ET-1 displaying the highest potency (7) whilst all three isopeptides displayed similar potencies in displacing 125I-labelled ET-1 from the other receptor (8). These two receptors are respectively what are now known as the ETA and ETB receptors and are classified on the basis of their rank order of potencies for the endothelins, being ET-1 = ET-2 ≫ ET-3 for the ETA receptor and ET-1 = ET-2 = ET-3 for the ETB receptor (9). These are the two receptors that mediate the effects of the endothelins in mammals, although additional receptor subtypes have been identified in a small number of other species (10, 11).

The amino acid sequences deduced from cloned ETA and ETB receptors predict that these receptors are heptahelical G-protein coupled receptors. In humans the ETA receptor is predicted to be 427 amino acids long, and shows approximately 64% sequence similarity to the predicted 442 amino acid long human ETB receptor (12). Endothelin receptors from several mammalian species display fairly high degrees of homology with the human ETA receptor (>90%) and ETB receptors (e.g. 97% for canine and 88% for rat) (9, 13).

Endothelin receptors are expressed by a wide variety of cells and tissues. A complex array of signaling molecules are employed by the receptors to achieve the diverse effects of endothelins on their target cells. Shraga-Levine and Sokolovsky (14) demonstrated using fibroblasts over expressing either one or the other of the two receptor subtypes, that ETA and ETB receptors couple to multiple classes of G proteins, and that this coupling varies depending upon both the receptor subtype and the ligand bound to the receptor in question. In the coming years, it is undoubtedly expected that further research in this complex but important area will gradually delineate the pathways that underlie the many physiological and pathophysiological actions of endothelins on different cells types.

ETA and ETB receptors in the vasculature

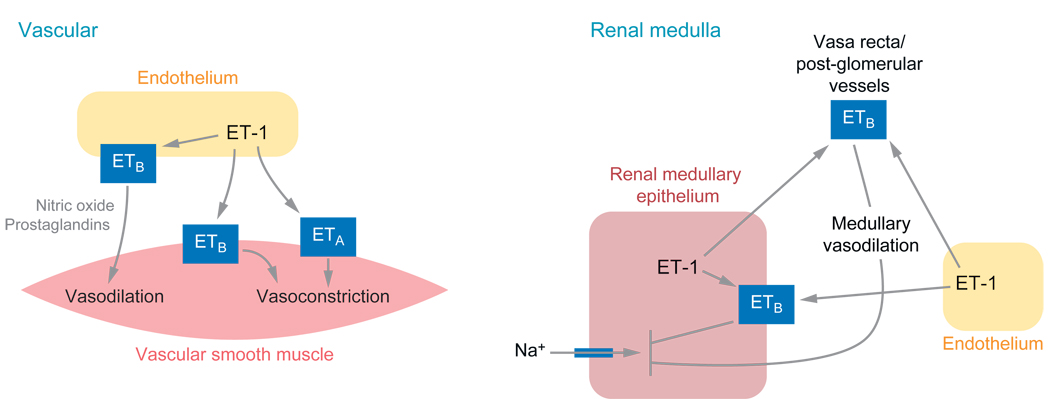

Both ETA and ETB receptors located on vascular smooth muscle mediate the potent vasoconstrictor effects that are characteristic of the endothelins (3). Although the precise signaling events responsible for endothelin-induced vasoconstriction in different vascular beds are still being actively investigated, it is commonly accepted that phospholipase C activation, inositol triphosphate generation and calcium mobilization from intra- and extra-cellular sources are involved. The ETB receptor exerts a dual role on vascular tone, as activation of ETB receptors located on the endothelium stimulates the production of nitric oxide and vasodilator cyclooxygenase metabolites, which exert vasorelaxant effects on the underlying smooth muscle (4). The predominant influence of endogenous endothelins on vascular tone and basal blood pressure is somewhat contentious. Acute ETA receptor blockade produces either a small decrease or no change in mean arterial pressure (15), perhaps suggesting that ETA receptors play relatively little role in determining basal vascular tone in healthy individuals. In contrast, acute and chronic ETB receptor blockade has consistently been shown to increase mean arterial pressure (16, 17), an effect that appears to involve enhanced ETA receptor activation but is also compounded by the loss of ETB receptor-mediated NO production. Thus it could be argued that the ETB receptor plays a more important role in the control of basal blood pressure and vascular tone than the ETA receptor, by protecting the vasculature against the potent vasoconstrictor effects of endogenous endothelins. There is also evidence that endogenously produced endothelins in healthy humans contribute to vascular tone with a limited degree of vasoconstriction. Supporting this contention includes the demonstration of increases in forearm blood flow in response to local infusion of the ECE inhibitor phosphoramidon (18) or non-selective endothelin receptor blockade (19). Further, systemic administration of combined ETA and ETB antagonists has been shown to produce mild decreases in total peripheral resistance and mean arterial pressure in healthy humans (20).

In addition to actions on vascular tone, endothelins also promote growth and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells, an effect that appears to be ETA receptor-mediated and involves activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases and perhaps the transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor (4). There is also direct and indirect evidence suggesting that endothelins stimulate oxidative stress in the vasculature, an effect that some studies have attributed primarily to the ETA receptor (21, 22). The deleterious vascular effects of endothelins, which have been the subject of much investigation in atherosclerosis, will be described in more detail below.

ETA and ETB receptors in the heart

Both ETA and ETB receptors are expressed in a heterogeneous manner throughout the human heart, with ETA receptors predominating on myocytes (reviewed by (23)). Endothelins have been reported to exert direct positive inotropic and, less frequently, positive chronotropic effects on the heart under various experimental conditions. The positive inotropic effects are thought to involve activation of protein kinase C and the Na+/H+ exchanger, resulting in sensitization of the myofilaments to Ca2+. The effects of endothelins on normal human cardiac function in vivo are somewhat unclear but may include a tonic ETA receptor-mediated contribution to left ventricular contractility. ET-1 has been shown to increase atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) mRNA and secretion from isolated atrial myocytes, apparently via ETA receptor activation (24). ETA receptor activation has also been reported to contribute to atrial stretch-induced release of ANP (25). As with vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelins have also been shown to stimulate hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes, an effect which has been shown in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes to be mediated by the ETA receptor and involves the actions of MAP kinases and reactive oxygen species (26).

ETA and ETB Receptors in The Lung

ETA receptors are expressed in the muscular media of human pulmonary arteries with stronger expression in proximal compared to distal arteries (27). The ETB receptor is also found on endothelial cells, the media, and the intima of pulmonary arteries. The expression of the ETB receptor in the intima is higher in proximal than in distal arteries, whereas medial ETB receptor expression is stronger in the distal vessels (27). These data on receptor expression obtained in rats seem to be confirmed by receptor binding studies in human lung tissue (28). Distal arteries possess both more binding sites in the media and a greater proportion of ETB receptors than proximal arteries (28). Furthermore, both ETA and ETB receptors were shown to mediate pulmonary smooth muscle cell proliferation in response to ET-1 (28).

ETA and ETB Receptors in The Kidney

As reviewed in detail by Kohan (29), most nephron segments can produce and bind endothelins. Autoradiographic studies of human kidneys have shown that binding of endothelin is greatest in the renal medulla, with lower levels of binding observed in the cortex (30, 31). The ratios of ETA to ETB receptors are similar in human cortex and medulla, varying from 1:2 to 20:80 depending on the technique used to quantify the receptors (31–33). In general, these receptor distributions are similar among various mammalian species.

The local endothelin system in the kidney plays an important role in the control of blood pressure through their effects on renal Na+ and water excretion. In the healthy kidney, endothelins are thought to act as diuretic and natriuretic agents, effects mediated predominantly via ETB receptors. Three main mechanisms are thought to contribute to the natriuretic and diuretic effects of endothelins. Firstly, endothelins inhibit Na+ and Cl− transport in several tubular segments, all of which predominantly express ETB receptors (29). Fluid and bicarbonate transport in the proximal tubule is inhibited by endothelins at least partly via suppression of Na+/K+ ATPase activity (34). Endothelin has been shown to inhibit Cl− reabsorption from cortical and medullary thick ascending limbs, which appears to be mediated, at least in the medulla, by an ETB receptor, NO-mediated mechanism (35, 36). There is also evidence that endothelin inhibits Na+/K+ ATPase activity in the collecting duct, an effect involving cyclooxygenase metabolites (37). Secondly, endothelin has been shown to inhibit vasopressin-induced water reabsorption by the collecting duct via ETB receptor-mediated inhibition of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) accumulation (38), although a recent study suggested that ETA receptors located on the collecting duct, albeit present in smaller numbers than ETB receptors, may somehow enhance collecting duct sensitivity to vasopressin (39). Finally, ETB receptor-activation increases renal medullary blood flow via NO and vasodilator cyclooxygenase metabolites (40), a hemodynamic mechanism thought to promote natriuresis. The ETB receptor-dependent enhancement of medullary blood flow may assume even greater importance during high dietary salt intake as rats maintained on a high salt diet display an enhanced ETB receptor-dependent increase of medullary blood flow in response to big ET-1 (41). A functionally intact endothelin system appears essential in order to increase sodium excretion appropriately and maintain a normal blood pressure during increases in dietary salt intake (17, 42, 43). This will be discussed further below, as dysfunction of this system is one possible cause of salt-sensitive hypertension.

ETB as a “Clearance” Receptor

Another important function of the ETB receptor is its action as a “clearance” receptor for endothelins. Following intravenous injection, ET-1 is rapidly removed from circulation, being retained in tissues (primarily the lungs, kidney and liver), and this effect is inhibited by ETB but not ETA receptor blockade (44). In further support of ETB receptor-mediated clearance of endothelin, plasma ET-1 concentrations are increased during ETB receptor blockade (45) and in rats genetically deficient in ETB receptors (42). The ability of the ETB receptor, but not the ETA receptor, to “clear” endothelins is not fully understood because studies have shown that ETA receptor selective antagonism can also elevate plasma ET-1 levels (46) and ETA binding kinetics are not too dissimilar to those of ETB receptors. The endothelin receptors bind ET-1 with extremely high affinity, with the half-life of dissociation from various tissues being > 30 hours in vitro (47). Although some studies have suggested that ET-1-ETB receptor complexes may be more stable than ET-1-ETA receptor complexes (48), the ETA receptor still binds endothelins extremely tight, with a half-time for dissociation of approximately 2 hours at 4°C even at acidic pH (49). Interestingly, this allows intact ET-1 to remain bound to the ETA receptor for as long as 2 hours even after the ligand-receptor complex has undergone endocytosis (49). An additional property which may underlie the apparently specific “clearance” function is that once ETB receptors bind endothelin, the receptors are internalized and targeted to the late endosomes/lysosomes for degradation, unlike ETA receptors which undergo recycling to the plasma membrane (50, 51). Finally, another possibility is that ETB receptors may simply be more readily accessible to circulating endothelins than are ETA receptors, perhaps because ETB receptors outnumber ETA receptors, or due to the close proximity of the pool of ETB receptors located on endothelial cells, resulting in more apparent changes in circulating ET-1 levels when the ETB receptor is blocked compared to the ETA receptor. Regardless of the mechanism involved, the role of the ETB receptor as a clearance receptor for endothelins should obviously be taken into consideration in the context of the treatment of cardiovascular diseases with endothelin receptor antagonists.

Dimerization of ETA and ETB receptors

Several unexpected interactions have been reported between ETA and ETB receptors in cells expressing both subtypes. For example, ETB receptors in the anterior pituitary gland appeared to only bind ET-1 during blockade of ETA receptors (52). Clearance of ET-1 by astrocytes and production of superoxide by rat aorta is blocked only by a combination of ETA and ETB receptor antagonists while being unaffected by administration of either agent alone (22, 53). Further, either ETA or ETB selective receptor antagonists can completely block the vasoconstrictor actions of ET-1 in renal afferent arterioles (54).

The existence of ETA-ETB heterodimers has been offered as a possible explanation for the aforementioned findings and these heterodimers may be the unidentified “atypical” endothelin receptor subtype reported in some studies (52, 55–57). Recently it was demonstrated that, at least in transfected cells, ETA and ETB receptors constitutively form heterodimers and homodimers (58, 59). Results thus far suggest that ETB receptors may internalize more slowly when present as ETA-ETB heterodimers, and that the heterodimers only dissociate following internalization after prolonged exposed to ETB receptor-selective agonists (58) whereas homodimers appear resistant to ligand-induced dissociation (59). Further studies will hopefully illuminate the functional consequences and significance of hetero- and homodimerization of endothelin receptors.

EVIDENCE FOR THE UTILITY OF ENDOTHELIN RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS

The considerable attention being paid to the endothelin system as a therapeutic target by many large and small pharmaceutical firms stems from the potential utility of endothelin receptor antagonists in the treatment of a wide range of cardiovascular diseases. There have been a number of very positive results in a variety of diseases, and in fact, the non-selective antagonist, bosentan, is currently on the market and being used clinically for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Despite intensive investigation, there remains considerable controversy as to whether ETA selective or non-selective, ETA/ETB receptor antagonists are preferable. In the end, this decision may be based on the particular disease and the specific pathology of the individual.

PULMONARY ARTERIAL HYPERTENSION

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a debilitating disease characterized by a sustained increase in pulmonary artery pressure due to elevated pulmonary vascular resistance. The prognosis of patients with untreated PAH is very poor and most patients die within 2–3 years after the diagnosis was made (60). The first significant improvements in prognosis were achieved with vasodilator therapy, such as with calcium channel blockers or prostaglandin administration. However, significant side effects and limited efficacy of these treatments highlight the need for new therapeutic options in this condition.

Circulating ET-1 levels were found to be elevated in patients with PAH, correlating with the severity of the condition (61). In addition, local pulmonary production of ET-1 was found to be strongly increased, both in animal models of PAH (62), in explanted lungs of adult patients with PAH (63) and in lung biopsies of pediatric patients with PAH (64). Pulmonary ETB receptors mediate clearance of about 50% of circulating ET-1 (65), and it has been suggested that pulmonary ET-1 clearance may be reduced in patients with PAH. However, it was shown recently that pulmonary clearance of ET-1 is intact in the majority of patients with PAH, indicating that elevated ET-1 levels are be mainly due to increased production rather than reduced clearance of circulating ET-1, although reduced clearance in other vascular beds cannot be ruled out (66).

In a hypoxia-induced model of PAH (27), ETA receptors in the media of distal arterial vessels were upregulated with no change of ETB receptor expression, whereas in the intima, ETB receptors were found to be upregulated (27). In contrast, expression of smooth muscle ETB receptors were shown to increase over time in an over circulation-induced model of PAH, which was associated with increased ETB receptor mediated vasoconstriction (67). In humans, binding sites for both receptor subtypes were found to be up-regulated in distal pulmonary arteries from patients with PAH (28).

In addition to these alterations in protein expression, functional changes of the pulmonary endothelin system have also been observed in models of PAH. The data are conflicting, and initial ETB receptor-mediated vasodilatory responses were found to be increased in some studies (68), but reduced in others (69). Likewise, the vasoconstrictor response to ET-1 mediated by smooth muscle ETA and ETB receptors was found to be enhanced in some (70) and reduced in other studies (71).

Pulmonary veins have attracted more attention recently, because it has been recognized that these post-capillary vessels contribute more to total pulmonary vascular resistance than previously assumed. Depending on the species studied, pulmonary veins contribute up to 50% of total pulmonary vascular resistance (72). ET-1 is a powerful vasoconstrictor of isolated human pulmonary veins, which show increased expression of big ET-1, ETA and ETB receptors in the media after exposure to hypoxia (73). This is in line with data showing increased ETB receptor-mediated vasoconstriction of pulmonary veins, but not arteries after hypoxia (74). Overall, these data indicate a substantial contribution of the local endothelin system in pulmonary veins to the degree of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension.

Interestingly, recent studies have shown that the signaling pathways utilized by ET-1 might change in rats exposed to prolonged hypoxia. Under normoxic conditions, ET-1 mediated vasoconstriction is largely calcium-dependent. However, the inhibitory effect of L-type calcium channel blockade on ET-1 mediated pulmonary vasoconstriction is reduced after prolonged hypoxia (75). Activation of tyrosine kinases and Rho kinase were recently shown to account for the ‘calcium sensitization’ of pulmonary arteries exposed to chronic hypoxia (76). Of note, Rho kinase inhibition has been demonstrated to effectively lower pulmonary vascular resistance in patients with PAH (77).

Oxidative stress has been shown to mediate some of the detrimental effects of ET-1 in the pulmonary circulation of the over circulation-induced model of PAH. By activating smooth muscle cell ETA receptors and perhaps also ETB receptors on endothelial cells, ET-1 increases the production of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide (21, 22, 78). These reactive oxygen species contribute to the proliferative response of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells to ET-1 and inhibit transcription of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and soluble guanylate cyclase (78, 79), further increasing pulmonary vascular resistance.

Endothelin Receptor Blockade in PAH

Endothelin receptor blockade has been uniformly shown to be an effective treatment strategy in a variety of animal models of PAH (Table 1). Two of these studies have directly compared the effectiveness of selective ETA receptor blockade versus nonselective ETA and ETB receptor blockade. In the first study, administration of the ETA selective antagonist ABT-627 or combined blockade of both receptors with ABT-627 and A-192621 had similar beneficial effects on right ventricular pressure and hypertrophy in monocrotaline-induced PAH (80). In the second study, the nonselective antagonist BSF420627, but not the ETA selective antagonist LU135252 reversed right ventricular hypertrophy and significantly increased survival in the same model (81). Differences in study design may explain the discrepancy of these findings. In the first study, treatment was started before induction of PAH, whereas treatment was started 2 weeks after induction of PAH in the second study, more realistically resembling the clinical scenario.

Table 1.

Endothelin receptor antagonists used in experimental studies of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

| Drug | Selectivity | ETAKi | ETBKi | Orally active (yes/no) |

Models investigated | Effect (+) beneficial (o) no effect (−) harmful |

Investigator, Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RO 47-0203 | ETA & ETB | 4.7 nM | 95 nM | Yes | Overcirculation | + | Rondelet, 2003 |

| (Bosentan) | Monocrotaline | + | Hill, 1997 | ||||

| Hypoxia | + | Holm, 1996 | |||||

| Hypoxia | + | Chen, 1995 | |||||

| Vascular Study | McCulloch, 1998 | ||||||

| SB217242 | ETA | 1.1 nM | 111 nM | Yes | Hypoxia | + | Underwood, 1998 |

| (Enrasentan) | Hypoxia | + | Underwood, 1997 | ||||

| Hypoxia | + | Underwood, 1999 | |||||

| Vascular Study | MacLean, 1998 | ||||||

| SB234551 | ETA | 0.1 nM | 500 nM | Yes | Vascular Study | MacLean, 1998 | |

| SB209670 | ETA & ETB | 0.2 nM | 12 nM | No | Vascular Study | McCulloch, 1998 | |

| Vascular Study | MacLean, 1998 | ||||||

| BSF420627 | ETA & ETB | 2.2 nM | 5.8 nM | Yes | Monocrotaline | + | Jasmin, 2001 |

| BQ123 | ETA | 22 nM | 18 µM | No | Overcirculation | + | Ivy, 1997 |

| Hypoxia | + | DiCarlo, 1995 | |||||

| Hypoxia | + | Oparil, 1995 | |||||

| Hypoxia | + | Bonvallet, 1994 | |||||

| Monocrotaline | + | Miyauchi, 1993 | |||||

| BQ-610 | ETA | 0.7 nM | 24 µM | No | Hypoxia | + | Ambalavanan, 2005 |

| Hypoxia | + | Ambalavanan, 2002 | |||||

| EMD122946 | ETA | 0.032 nM | 160 nM | No | Hypoxia | + | Ambalavanan, 2002 |

| TBC3711 | ETA | 0.08 nM | 26.3 µM | Yes | Hypoxia | + | Perreault, 2001 |

| TBC11251 | ETA | 1.4 nM | 9.8 µM | Yes | Monocrotaline | + | Tilton, 2000 |

| (Sitaxsentan) | |||||||

| TA-0201 | ETA | 0.015 nM | 41 nM | Yes | Monocrotaline | + | Ueno, 2000 |

| Monocrotaline | + | Ueno, 2002 | |||||

| BMS-193884 | ETA | 1.4 nM | 18.8 µM | Yes | Monocrotaline | + | Miyauchi, 2000 |

| ZD1611 | ETA | 8.6 nM | 5.6 µM | Yes | Hypoxia | + | Bialecki, 1999 |

| Hypoxia | + | Bialecki, 1998 | |||||

| FR 139317 | ETA | 1 nM | 7 µM | No | Vascular Study | McCulloch, 1998 | |

| ABT-627 | ETA | 0.034 nM | 63.3 nM | Yes | Monocrotaline | + | Nishida, 2004 |

| (Atrasentan) | Monocrotaline | + | Nishida, 2004 | ||||

| BMS 182874 | ETA | 55 nM | >200 µM | Yes | Vascular Study | McCulloch, 1998 | |

| YM598 | ETA | 0.697 nM | 569 nM | Yes | Hypoxia | + | Yuyama, 2005 |

| Monocrotaline | + | Yuyama, 2004 | |||||

| Monocrotaline | + | Fujimori, 2004 | |||||

| LU135252 | ETA | 1.4 nM | 140 nM | Yes | Monocrotaline | + | Jasmin, 2003 |

| (Darusentan) | Monocrotaline | + | Jasmin, 2001 | ||||

| Monocrotaline | + | Prie, 1998 | |||||

| Monocrotaline | + | Prie, 1997 | |||||

| Hypoxia | + | Blumberg, 2003 | |||||

| PD-155080 | ETA | 221.4 nM | 86.5 µM | Yes | Monocrotaline | + | Stessel, 2004 |

| PD-156707 | ETA | 0.17 nM | 133.8 nM | Yes | Overcirculation | + | Fratz, 2004 |

| Hypoxia | + | Sheedy, 1998 | |||||

| Hypoxia | + | Haleen, 1998 | |||||

| Vascular Study | Black, 2003 |

The non-selective ET antagonist, bosentan, was the first, and currently the only, ET antagonist currently on the market for the treatment of PAH. Food and Drug Administration approval was based in large measure by combined data from two extended clinical trials that showed survival rate of patients treated with bosentan of 86% after three years, as compared to a predicted 48% based on historical data from the National Institutes of Health (60). In addition, it was also shown that bosentan at a dose of 125 mg or lower is effective and safe in children (82).

To date, two clinical trials with newer ETA receptor-selective antagonists have been completed. Both sitaxsentan and ambrisentan led to improvements in the 6-minute walk test and several secondary endpoints (83, 84). The advantages of ambrisentan seems to be a lower, non-dose dependent incidence of liver toxicity, less interaction with other drugs and the option of once-daily dosing due to a long half-live (9 to 15 hours). In the subsequent phase III ARIES II trial, ambrisentan at doses of 2.5 and 5 mg qd improved exercise capacity without clinically significant increases in liver enzymes (http://www.myogen.com).

Selective ETA Receptor Blockade or Nonselective ETA and ETB Receptor Blockade?

Although ETB receptor deficiency has been shown to potentiate hypoxia-induced PAH in rats (85), both selective and nonselective endothelin receptor blockade effectively ameliorate the progression of PAH in clinical trials. So far, no clinical study has made a direct comparison of ETA selective versus nonselective ETA/ETB antagonists in patients with PAH. Based on the role of the renal tubular ETB receptor in mediating sodium excretion, differences in the use of diuretics and in the occurrence of edema might be anticipated. Rates of edema were not reported in the any of the bosentan trials, but patients treated with the ETA selective receptor antagonist sitaxsentan in the STRIDE-1 trial did not suffer a higher rate of peripheral edema than patients in the placebo group (21% versus 17%, n.s.).

CHRONIC HEART FAILURE

Circulating levels of ET-1 are elevated in patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) caused by a combination of increased production and reduced clearance of ET-1 (86). Furthermore, activation of the endothelin system contributes to peripheral vasoconstriction and impaired endothelial function in patients with CHF (87), and plasma ET-1 levels were shown to predict survival (88). In the majority of animal models, the expression of ET-1 in the left ventricle was found to be upregulated (89). Some studies found upregulation of either ETA or ETB receptors, and sometimes both receptors (89–92). In humans, left ventricular expression of ET-1 and ETA receptors were found to be increased, with no change in ETB receptors (93). Despite the upregulation of ETA receptors, the inotropic response to ET-1 is reduced in failing hearts, indicating reduced post-receptor signaling efficiency.

Endothelin Receptor Blockade in CHF

Most studies in animal models of CHF demonstrated beneficial effects of selective ETA receptor blockade on cardiac function and overall mortality, and the same is true for most studies with nonselective receptor blockade (Table 2). Only two of these animal studies compared selective versus nonselective blockade directly. Both studies found that the effects on hemodynamics and cardiac function were similar (94, 95).

Table 2.

Endothelin receptor antagonists used in experimental studies of heart failure

| Drug | Selectivity | ETAKi | ETBKi | Orally active (yes/no) |

Models investigated | Effect (+) beneficial (o) no effect (−) harmful |

Investigator, Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RO 47-0203 | ETA & ETB | 4.7 nM | 95 nM | Yes | Coronary ligation | + | Mulder, 1997 |

| (Bosentan) | Coronary ligation | + | Oie, 1998 | ||||

| Coronary ligation | + | Fraccarollo, 1997 | |||||

| RO 61-0612 | ETA & ETB | 0.3 nM | 10 nM | No | Coronary ligation | + | Clozel, 2002 |

| (Tezosentan) | Coronary ligation | + | Qiu, 2001 | ||||

| BQ 123 | ETA | 22 nM | 18 µM | No | Coronary ligation | + | Sakai, 1996 |

| SB 209670 | ETA & ETB | 0.2 nM | 12 nM | No | Coronary ligation | − | Oie, 2002 |

| YM598 | ETA | 0.697 nM | 569 nM | Yes | Coronary ligation | + | Miyauchi, 2004 |

| Coronary ligation | + | Fujimori, 2004 | |||||

| ABT-627 | ETA | 0.034 nM | 63.3 nM | Yes | J2N-k cardiomyopathy | + | Nishida, 2005 |

| (Atrasentan) | Coronary ligation | + | Mulder, 2000 | ||||

| LU135252 | ETA | 1.4 nM | 140 nM | Yes | ET-1 overexpression | 0 | Yang, 2004 |

| (Darusentan) | Rapid pacing | − | Schirger, 2004 | ||||

| Coronary ligation | 0 | Mulder, 2002 | |||||

| Rapid pacing | + | Moe, 1998 | |||||

| Coronary ligation | + | Mulder, 1998 | |||||

| Coronary ligation | 0 | Fraccarollo, 2002 | |||||

| LU420627 | ETA & ETB | 2 nm | 6 nm | yes | ET-1 overexpression | + | Yang, 2004 |

| Coronary ligation | − | Nguyen, 2001 | |||||

| FR139317 | ETA | 1 nM | 7 µM | No | Coronary ligation | + | Chen, 2001 |

| Rapid pacing | + | Ohnishi, 1998 | |||||

| TA-0201 | ETA | 0.015 nM | 41 nM | Yes | Cardiomyopathy | + | Yamauchi-Kohno, 1999 |

| Rapid pacing | + | Ohnishi, 1998 | |||||

| TAK-044 | ETA & ETB | 0.08 nM | 120 nM | No | Rapid pacing | + | Ohnishi, 1998 |

| A-127722 | ETA | 0.082 nM | 114 nM | Yes | Rapid pacing | + | Borgeson, 1998 |

| PD 156707 | ETA | 0.17 nM | 133.8 nM | Yes | Rapid pacing | + | Spinale, 1997 |

| Rapid pacing | + | McConnell, 2000 |

Early studies showed that endothelin blockade has beneficial hemodynamic effects in humans with CHF. Two recent clinical studies compared the hemodynamic effects of selective versus nonselective endothelin receptor blockade directly. In the first study (96), similar reductions of pulmonary and peripheral vascular resistance and increases in cardiac output were produced by the two types of antagonists, whereas in the second study (97), these effects were found to be more pronounced with selective ETA receptor blockade. In both studies, circulating ET-1 levels were only raised by nonselective receptor blockade. The clinical significance of a further increase in plasma ET-1 levels with nonselective blockade is unknown, but may be of minor importance when ETA receptors are fully blocked.

The ENCOR trial was the first trial to examine the effects of endothelin receptor blockade in patients with CHF (98). Treatment with the nonselective antagonist, enrasentan, unfortunately led to a deterioration in clinical status and a tendency to increase mortality, as compared with the placebo treated group. A more recent study also showed that enrasentan has adverse effects on left ventricular structure in patients with asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction (99). In the REACH-1 trial, patients with CHF were treated with bosentan, but the study was interrupted early because of a high incidence of elevated liver enzymes (100). In the subsequent ENABLE 1 and 2 trials, a lower dose of 125 mg bid reduced hepatotoxicity did not improve outcome as compared to placebo (101). Especially in the first 2 weeks of treatment, bosentan led to a high incidence of fluid retention and edema.

So far, two trials have examined the long-term effects of selective ETA receptor blockade in patients with CHF. In the HEAT trial, the hemodynamic effects of selective ETA receptor blockade with darusentan were determined before and after 3 weeks of treatment (102). Although there was a significant increase in cardiac output with active treatment, major safety concerns were raised following 4 deaths in the darusentan treated group. In addition, this study showed an increase in plasma ET-1 levels at the higher doses of darusentan, indicating that blockade of the ETA receptor can increase circulating ET-1 levels in CHF. The EARTH trial failed to detect a beneficial effect of 6 months treatment with darusentan on left ventricular remodeling in patients with CHF (103). At this point, it is not clear why, but the beneficial effects in the acute hemodynamic studies of either selective or non-selective ET antagonists do not appear to translate into clinical benefits during long-term treatment.

Endothelin Antagonists in Acute Heart Failure

Several small studies have shown beneficial effects of the non-selective ET receptor antagonist, tezosentan, on hemodynamic parameters in patients with acute heart failure. The larger VERITAS trial then examined the effect of tezosentan on the mortality of patients hospitalized with acute heart failure (104). Similar to the situation in chronic heart failure, the trial had to be discontinued prematurely because of lack of a beneficial effect on mortality (104).

Novel Aspects of Endothelin Action in CHF

A recent study suggested that the effects of endothelin receptor blockade, beneficial or harmful, may crucially depend on the stage of CHF when therapy is initiated (105). These investigators also reported that selective ETA receptor blockade during an early stage of CHF caused sustained sodium retention by activating the renin-angiotensin system (105). Another recent study describes a new genetic model of CHF in mice produced by cardiac-specific over-expression of ET-1 (106). The mice suffered cardiac hypertrophy, inflammation, dilation and subsequently death. It has to be noted, however, that the levels of ET-1 in the hearts of the transgenic mice were 10 times greater than in the control mice compared to 3-fold increases reported in humans with CHF (106). Although highly problematic given the negative findings in human CHF, this study raises the question of whether there could be a role for endothelin blockade in inflammatory cardiac disease, such as in the early stages of virally induced cardiomyopathies.

ESSENTIAL HYPERTENSION

Plasma ET-1 concentrations have been reported to be elevated in patients with essential hypertension in some but not all studies (reviewed in (107)). However, since secretion of ET-1 from endothelial cells is polar, with the majority of ET-1 likely to be secreted towards the media rather than lumen of blood vessels (108), plasma ET-1 concentrations may not give a reliable indication of local vascular exposure to ET-1.

Consistent with a role for ET-1 in hypertension, an enhanced contribution of endogenous ET-1 to forearm vascular tone in patients with essential hypertension has been reported (109). In patients with essential hypertension, forearm vasodilation in response to selective ETA receptor blockade or nonselective endothelin receptor blockade was found to be enhanced compared to normotensive subjects (109), although other studies did not find such a difference (19, 110). One study directly compared the vasodilatory response of ETA versus ETA/ETB blockade in the forearm vasculature of patients with essential hypertension and found that nonselective blockade had a greater vasodilatory effect than selective ETA receptor blockade in these patients (109), perhaps indicating a greater contribution of smooth muscle cell ETB receptors to vascular tone or impaired endothelial cell ETB receptor-mediated vasodilator production in patients with hypertension.

Despite these encouraging data, few studies have examined the long-term blood pressure lowering potential of endothelin receptor antagonists. In patients with essential hypertension, the non-selective antagonist, bosentan, and the ETA antagonist, darusentan, reduce blood pressure to a similar extent as enalapril (111, 112). However, these drugs are not used clinically to treat patients with essential hypertension, mainly because of the relatively high liver toxicity, greater incidence of other less severe side effects such as headache and peripheral edema as well as greater costs compared to established anti-hypertensive drugs.

Endothelin receptor blockade may have greater benefits in certain subgroups of patients with hypertension, such as diabetics, African-Americans and obese patients. In these subgroups, the contribution of ET-1 to vascular tone has been shown to be even more pronounced (113–115). Endothelin receptor blockade could also be of value in patients with resistant hypertension, where blood pressure remains uncontrolled despite therapy with 3 or more antihypertensive agents. Darusentan (Myogen) and Thelin (Encysive) are currently being evaluated for the treatment of resistant hypertension.

Although great progress has been made in the treatment of hypertension, blood pressure control is still achieved only in about 30% of patients (116). Control of blood pressure is particularly difficult in elderly subjects with isolated systolic hypertension. In contrast to the hypertension found in younger subjects, isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly is pathogenetically different, being strongly associated with increased arterial stiffness. Agents that interfere with the progression of arterial stiffness might be particularly suited to treat isolated systolic hypertension. In animal experiments, ET-1 has recently been shown to directly increase arterial stiffness, and conversely, ETA receptor blockade has been shown to directly decrease arterial stiffness (117). Thus, endothelin antagonists might be useful in the treatment of isolated systolic hypertension through direct effects on the vasculature. Due to the action of the ETB receptor to “clear” endothelin and to facilitate renal salt and water excretion (see above), it would appear preferable to treat hypertensive patients with ETA receptor antagonists rather than nonselective endothelin receptor antagonists.

Interestingly, some studies suggest that reduced renal production of ET-1 might contribute to the development of hypertension. Several lines of evidence demonstrate that urinary excretion of endothelin specifically reflects renal endothelin production. Renal endothelin production is increased in experimental animals given a high salt diet (17) and changes in sodium excretion are tightly correlated to urinary excretion of ET-1 in humans (118). Patients with hypertension, in particular those with salt-sensitive hypertension, were found to excrete less ET-1 in their urine than normotensive subjects, indicating reduced renal ET-1 production in the hypertensive subjects (119). Reduced production of ET-1 in the renal medulla has also been found in some animal models of hypertension (120, 121). Underlining the importance of the intrarenal endothelin system in the control of blood pressure and sodium and water homeostasis, mice with collecting duct-specific knockout of the ET-1 gene are hypertensive on a normal salt diet, and this hypertension is exacerbated by exposure to a high salt diet (43). Further, studies in rats have shown that blockade of ETB receptors or genetic ETB receptor deficiency leads to salt-sensitive hypertension (17, 42). These observations support the hypothesis that a deficiency in renal endothelin production or an impairment of its actions reduces the ability of the kidney to excrete excess Na+, leading to the development of salt-sensitive hypertension.

KIDNEY DISEASE

The renal circulation is particularly sensitive to the effects of intravenous infusion of ET-1 that reduces renal blood flow, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and sodium excretion in humans in the absence of changed in systemic hemodynamics and is mediated mainly by ETA receptors (122). After treatment with the ETA receptor antagonist, ABT-627, for one week, no change was observed in renal hemodynamics, indicating a minor role for endogenous endothelin in the regulation of renal vascular tone in healthy subjects (122).

In patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), selective blockade of ETA receptors increased renal blood flow and reduced blood pressure, filtration fraction, and proteinuria to a greater extent compared to healthy controls (123). Thus, patients with CKD appear to have increased ETA receptor-mediated renal vascular tone. In both patients with CKD and healthy controls, ETB receptor blockade reduced renal blood flow despite an increase in systemic blood pressure (123). Nonselective endothelin receptor blockade did not change renal blood flow in patients with CKD or in healthy controls (123). Taken together, these data indicate that ETB receptors have a predominantly vasodilatory action in the human renal circulation, in healthy subjects and in patients with CKD. Based on these results, selective ETA receptor blockade may be more beneficial than nonselective endothelin receptor blockade in patients with CKD.

ET-1 has also been implicated directly in the cellular pathology of several forms of renal disease. The renal endothelin system is activated in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and is considered to be a disease-modifying factor (124). ET-1 seems to promote cyst-formation, and furthermore, ETA receptor blockade has been shown to increase cyst formation in the Han:SPRD rat, an animal model of ADPKD (125). In most, but not all, models of renal disease, however, selective ETA receptor blockade as well as non-selective blockade have both been shown to be beneficial (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Endothelin receptor antagonists used in experimental studies of chronic kidney disease

| Drug | Selectivity | ETAKi | ETBKi | Orally active (yes/no) |

Models investigated | Effect (+) beneficial (o) no effect (−) harmful |

Investigator, Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RO 47-0203 | ETA & ETB | 4.7 nM | 95 nM | Yes | Ren-2 rat | + | Dvorak, 2004 |

| (Bosentan) | Ren-2 rat | Opocensky, 2004 | |||||

| Ren-2 rat | Vaneckova, 2005 | ||||||

| STZ rat | + | Cosenzi, 2003 | |||||

| STZ rat | + | Ding, 2003 | |||||

| Glomerulonephritis | + | Gomez-Garre, 1996 | |||||

| 5/6 nephrectomy | + | Benigni, 1996 | |||||

| RO 48-5695 | ETA & ETB | 0.7 nM | 5 nM | Yes | 5/6 nephrectomy | 0 | Clozel, 1999 |

| RO 46-2005 | ETA & ETB | 220 nM | 1 µM | Yes | 5/6 nephrectomy | + | Nabokov, 1996 |

| ABT-627 | ETA | 0.034 nM | 63.3 nM | Yes | Ren-2 rat | + | Vaneckova, 2005 |

| (Atrasentan) | Hypokalemia | + | Suga, 2003 | ||||

| LU 224332 | ETA & ETB | 3.5 nM | 7.2 nM | Yes | Transplant | 0 | Braun, 2000 |

| nephropathy | |||||||

| Han:SPRD rat | − | Hocher, 2003 | |||||

| STZ rat | + | Hocher, 2001 | |||||

| LU 302146 | ETA | 0.9 nM | 73 nM | Transplant | + | Adams, 2002 | |

| nephropathy | + | Knoll, 2003 | |||||

| LU 135252 | ETA | 1.4 nM | 140 nM | Yes | Transplant | + | Braun, 1999 |

| (Darusentan) | nephropathy | + | Orth, 1999 | ||||

| + | Orth, 1998 | ||||||

| SHR-SP | + | Trenkner, 2002 | |||||

| SHR | + | Brochu, 1999 | |||||

| 5/6 nephrectomy | + | Amann, 2001 | |||||

| 5/6 nephrectomy | − | Hocher, 2003 | |||||

| Han:SPRD rat | + | Hocher, 2001 | |||||

| STZ rat | 0 | Gross, 2003 | |||||

| STZ rat | + | Dhein, 2000 | |||||

| Ren-2 | 0 | Rothermund, 2003 | |||||

| Glomerulosclerosis | + | Ortmann, 2004 | |||||

| Sabra rat | + | Rothermund, 2003 | |||||

| SHR/N-cp | + | Gross, 2003 | |||||

| LU 420627 | ETA & ETB | 2 nM | 6 nM | Yes | Ren-2 | 0 | Rothermund, 2003 |

| BQ-123 | ETA | 22 nM | 18 µM | No | 2K1C | − | Hocher, 2000 |

| SHR-SP | + | Okada, 1995 | |||||

| FR139317 | ETA | 1 nM | 7 µM | No | 5/6 nephrectomy | 0 | Kohzuki, 1998 |

| 5/6 nephrectomy | + | Benigni, 1993 | |||||

| IgA-nephropathy | + | Nakamura, 1996 | |||||

| STZ | + | Nakamura, 1995 | |||||

| PAN-nephrosis | + | Ebihara, 1997 | |||||

| Lupus-nephritis | + | Nakamura, 1995 | |||||

| YM 598 | ETA | 0.697 nM | 569 nM | Yes | OLETF rats | + | Sugimoto, 2002 |

| PD 142893 | ETA & ETB | 31 nM | 54 nM | Yes | STZ | + | Benigni, 1998 |

| PD 155080 | ETA | 221.4 nM | 86.5 µM | Yes | 5/6 nephrectomy | 0 | Potter, 1997 |

| A-127722 | ETA | 0.082 nM | 114 nM | Yes | 5/6 nephrectomy | 0 | Pollock, 1997 |

| BMS-182874 | ETA | 55 nM | >200 µM | Yes | 5/6 nephrectomy | + | Nabokov, 1996 |

Podocytes have attracted increasing attention recently in the context of renal glomerular injury. Podocyte dysfunction leads to breakdown of the glomerular filtration barrier, proteinuria and subsequent kidney damage. ET-1 synthesis is increased in dysfunctional podocytes (126), which promotes contraction of podocytes and neighboring mesangial cells and further increases in protein filtration. ETA receptor blockade has recently been shown to reverse established glomerulosclerosis and proteinuria in a model of focal-segmental glomerulosclerosis by more than 50%(127). In addition to podocytes, increased ET production by tubular epithelial cells also has been shown to contribute to renal tubular injury (128). In line with these data, urinary ET-1 excretion is increased in patients with proteinuric kidney disease and decreases after treatment of the underlying renal disease, e.g. by immunosuppressive therapy (129).

With the exception of ADPKD and renal artery stenosis, endothelin receptor blockade may have beneficial effects in most forms of kidney disease although targeted clinical studies in patients with CKD are lacking. In a recent phase II trial, avosentan was shown to reduce proteinuria in patients with diabetic nephropathy by about 30%, even though these patients were already being treated with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker. The evaluation of avosentan has now moved into a large phase III trial (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT00120328), where the long-term effects on morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetic nephropathy will be investigated. Interestingly, a recent preliminary study by Sasser and colleagues demonstrated that 8 week treatment with atrasentan in an animal model of type I diabetes demonstrated reduced proteinuria and reduced renal inflammation (unpublished data). These findings are consistent with studies in heart failure mentioned above where ETA blockade reduced inflammation in the heart.

In addition to CKD, blocking the endothelin system may also be beneficial in acute renal failure (ARF). ET-1 and both receptors are upregulated after an ischemic insult to the kidney, in particular in areas of tubular damage (130). Whether the changes in the expression of the endothelin system are beneficial or detrimental for the recovery of kidney structure and function remains ill defined. Several experimental studies have attempted to define the role of endothelin in ARF with most studies reporting beneficial effects of ET receptor blockade (Table 4). However, one large study investigating the effect of nonselective endothelin receptor blockade with SB 290670 in patients with CKD undergoing coronary angiography reported that patients receiving SB 290670 were more likely to develop radiocontrast-induced ARF than those receiving placebo (131). The interest in endothelin antagonists in the prevention and treatment of ARF has considerably declined after these discouraging results although the question of whether ETA receptor-selective compounds may provide benefit has not been adequately investigated.

Table 4.

Endothelin receptor antagonists used in experimental studies of acute renal failure

| Drug | Selectivity | ETAKi | ETBKi | Orally active (yes/no) |

Models investigated | Effect (+) beneficial (o) no effect (−) harmful |

Investigator, Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RO 47-0203 | ETA & ETB | 4.7 nM | 95 nM | Yes | Post-ischemia | + | Jerkic, 2004 |

| (Bosentan) | Rhabdomyolysis | + | Karam, 1995 | ||||

| RO 61-0612 | ETA & ETB | 0.3 nM | 10 nM | No | Post-ischemia | + | Wilhelm, 2001 |

| (Tezosentan) | |||||||

| LU 135252 | ETA | 1.4 nM | 140 nM | Yes | Transplant rejection | + | Braun, 2000 |

| (Darusentan) | Post-ischemia | + | Knoll, 2001 | ||||

| Post-ischemia | Birck, 1998 | ||||||

| SB 234551 | ETA | 0.13 nM | 500 nM | Yes | Post-ischemia | + | Forbes, 2001 |

| SB 209670 | ETA & ETB | 0.2 nM | 12 nM | No | Post-ischemia | + | Huang, 2002 |

| Post-ischemia | − | Forbes, 2001 | |||||

| Post-ischemia | 0 | Forbes, 1999 | |||||

| Post-ischemia | + | Brooks, 1994 | |||||

| Post-ischemia | + | Gellai, 1995 | |||||

| Post-ischemia | + | Ajis, 2003 | |||||

| Radiocontrast | + | Brooks, 1996 | |||||

| Endotoxin | 0 | Wellings, 1995 | |||||

| UK-350926 | ETA | 0.1 nM | No | Post-ischemia | + | Huang, 2002 | |

| Post-ischemia | − | Ajis, 2003 | |||||

| ABT-627 | ETA | 0.034 nM | 63.3 nM | Yes | Post-ischemia | + | Kuro, 2000 |

| PD-156707 | ETA | 0.17 nM | 133.8 nM | Yes | Post-ischemia | 0 | Forbes, 1999 |

| A-127722 | ETA | 0.082 nM | 114 nM | Yes | Radiocontrast | + | Pollock, 1997 |

| L-754142 | ETA & ETB | 0.062nM | 2.25 nM | Yes | Post-ischemia | + | Krause, 1997 |

| BMS-182874 | ETA | 55 nM | >200 µM | Yes | Radiocontrast | + | Bird, 1996 |

| BQ-123 | ETA | 22 nM | 18 µM | No | Post-ischemia | 0 | Brooks, 1994 |

| Post-ischemia | + | Gellai, 1994 | |||||

| Post-ischemia | + | Chan, 1994 | |||||

| Cyclosporine | + | Fogo, 1992 | |||||

| TAK-044 | ETA & ETB | 0.08 nM | 120 nM | No | Post-ischemia | + | Kusumoto, 1994 |

ATHEROSCLEROSIS

It has been well documented that vascular endothelin production is elevated in atherosclerosis and influences the development of atherosclerotic lesions through a variety of mechanisms. In forearm blood flow studies in patients with atherosclerosis, there is increased ETB receptor dependent vasoconstriction compared to controls (132). Non-selective blockade of endothelin receptors produced a greater increase in forearm blood flow than ETA receptor-selective blockade in patients with atherosclerosis, suggesting enhanced ETB receptor mediated vasoconstriction (133). However, elevated ET-1 levels have been shown to impair endothelial function, and selective blockade of ETA receptors improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in the forearm circulation of patients with atherosclerosis (134). Since the brachial artery rarely develops atherosclerosis, the pathophysiological significance of these findings is not clear. Furthermore, in patients with coronary artery disease, intracoronary infusion of the ETA receptor antagonist, BQ-123, led to vasodilation and local improvement of endothelium-dependent vasodilation (135). This indicates that ET-1 contributes to coronary vascular tone and endothelial dysfunction in patients with coronary artery disease through actions via the ETA receptor. The role of coronary ETB receptors was not examined in this study.

In human atherosclerotic lesions, enhanced expression of ETB receptors in the intima and media was found, particularly in areas underlying an atherosclerotic plaque (136). While this increased expression of smooth muscle cell ETB receptors could explain the increased vasoconstrictor effects of sarafotoxin S6c in the human forearm vasculature (132), it is tempting to speculate that increased ETB receptor expression may be a consequence of increased ET-1 production in an attempt to facilitate clearance of the peptide.

Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease, and monocyte/macrophage infiltration of the vasculature is a key event in initiation and progression of atherosclerotic lesions. Endothelin stimulates production of inflammatory cytokines and influences several crucial steps in the inflammatory component of atherosclerosis. This includes increasing the release of various cytokines from monocytes (137) and enhancing the uptake of LDL cholesterol by these cells, promoting a phenotypic change into foam cells (138). ETB receptors, but not ETA receptors, were found on macrophages that infiltrated atherosclerotic vessels (139). Cytokines released from monocytes/macrophages, in turn, stimulate ET-1 production (140), providing positive feedback for further cytokine production.

Plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration has been shown to be an independent predictor of cardiovascular mortality and may also directly affect the progression of atherosclerosis by upregulating vascular expression of adhesion molecules, cytokines and chemokines. Interestingly, these effects seem to be dependent on the endothelial release of ET-1 (141). Bosentan was shown to inhibit CRP-induced upregulation of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and MCP-1 on endothelial cells. This effect most likely derives from blockade of ETB receptors, the subtype of endothelin receptors found on endothelial cells.

These data overall seem to suggest that ETB receptors have predominantly pro-atherosclerotic effects. However, several anti-atherosclerotic effects are also clearly mediated by ETB receptors because of its ability to release NO (142). Whether ETB receptor blockade is beneficial or harmful in patients with atherosclerosis is therefore difficult to predict. In several animal models, both ETA receptor selective and nonselective endothelin receptor blockade has been shown to inhibit the development of atherosclerotic lesions (138, 143–147). No studies so far have compared ETA receptor selective and nonselective strategies directly.

SIDE BAR

Endothelin as a modulator of the sympathetic nervous system?

Evidence to date suggests that both endothelin receptor subtypes, but particularly the ETB receptor, may have complex interactions with the sympathetic nervous system at the pre- and post-junctional level. Studies of vessel-nerve preparations found that endothelins can inhibit electrical stimulus-evoked sympathetic neurotransmitter release, but similar or slightly greater concentrations of ET-1 can also facilitate transmitter release and/or potentiate norepinephrine-induced vasoconstriction (148, 149). More recent interest has centered on findings that activation of neuronal ETB receptors increases O2− production (150, 151). Other studies have provided evidence that reactive oxygen species can enhance peripheral and centrally-mediated sympathetic nerve activity. In direct contrast with this yet-to-be confirmed ETB and O2−-mediated stimulatory effect, earlier studies reported that ETB receptor activation inhibits norepinephrine release from electrically stimulated renal sympathetic nerves in vivo, an effect apparently involving NO (152). While these seemingly disparate findings have yet to be reconciled and more investigation is needed, a combination of several key factors, including the source of the endothelin (e.g. endogenous generation versus pharmacological administration), the cell type(s) harboring the stimulated receptors, and the chemical mediators generated, likely determine the final effects of endothelins on sympathetic function.

SUMMARY

In general, the detrimental vascular effects of ET-1 such as growth and smooth muscle proliferation are mediated by the ETA receptor while ETB receptors have opposing effects to produce endothelial-dependent vasodilation, promote natriuresis by inhibiting renal sodium reabsorption, and clearing ET-1 from the circulation.

However, the question remains whether ETA selective or non-selective ETA/ETB receptor antagonists should be used to treat various clinical conditions because ETB receptors on vascular smooth muscle contribute to vasoconstriction in some circumstances and/or locations.

Although the expression of both ETA and ETB receptors in the pulmonary vasculature is increased in pulmonary arterial hypertension, it is not clear whether blocking the ETB receptor is beneficial or harmful in this setting since both ETA selective and non-selective ETA/ETB receptor antagonists are beneficial.

Surprisingly, clinical trials using either selective or non-selective antagonists for the treatment of heart failure actually produced detrimental effects despite the fact that many studies in animal models have been very promising.

Both ETA selective and non-selective ETA/ETB receptor antagonists effectively lower blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension and may improve renal function in diabetic nephropathy. However, vigorous pursuit of these indications has been slow to develop due, in large measure, to the existing availability of highly effective and less expensive antihypertensive drugs.

UNRESOLVED ISSUES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Non-selective ETA/ETB antagonists are currently being used for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension and selective ETA antagonists should be approved soon. This will allow resolution of the hotly debated question of whether one type of antagonist has a clinical advantage over the other.

The broad use of endothelin receptor antagonists to treat essential hypertension currently appears unlikely since there is little evidence of an advantage over current therapies. However, future studies may help determine whether these drugs should be used clinically to treat so-called resistant hypertension especially as a co-therapy.

Blockade of endothelin receptors has proven to be beneficial in a variety of animal models of other cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis and diabetic nephropathy; whether these promising results translate to the clinic remains to be determined.

Elucidating the yet unknown functional consequences of endothelin receptor hetero- and homodimerization should help clarify many physiological and pathophysiological issues related to the endothelin story.

Current knowledge of endothelin receptor-specific actions within the sympathetic nervous system is in its infancy, but is expected to be extremely important in modulating cardiovascular function in health and disease.

Figure 1.

Receptor-specific actions of endothelin that influence blood pressure control

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Dr Pollock is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association and is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL64776 and HL74167). Dr Schneider is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SCHN 769/1-1).

LITERATURE CITED

- 1. Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, Tomobe Y, Kobayashi M, et al. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 1988;332:411–415. doi: 10.1038/332411a0. Initial purification and characterization of endothelin

- 2.Inoue A, Yanagisawa M, Kimura S, Kasuya Y, Miyauchi T, et al. The human endothelin family: three structurally and pharmacologically distinct isopeptides predicted by three separate genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:2863–2867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubanyi GM, Polokoff MA. Endothelins: molecular biology, biochemistry, pharmacology, physiology, and pathophysiology. Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46:325–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kedzierski RM, Yanagisawa M. Endothelin system: the double-edged sword in health and disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:851–876. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeng AY. Utility of endothelin-converting enzyme inhibitors for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;4:1076–1081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Orleans-Juste P, Plante M, Honore JC, Carrier E, Labonte J. Synthesis and degradation of endothelin-1. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;81:503–510. doi: 10.1139/y03-032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arai H, Hori S, Aramori I, Ohkubo H, Nakanishi S. Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding an endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:730–732. doi: 10.1038/348730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Takuwa Y, Miyazaki H, Kimura S, et al. Cloning of a cDNA encoding a non-isopeptide-selective subtype of the endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:732–735. doi: 10.1038/348732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davenport AP. International Union of Pharmacology. XXIX. Update on endothelin receptor nomenclature. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:219–226. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karne S, Jayawickreme CK, Lerner MR. Cloning and characterization of an endothelin-3 specific receptor (ETC receptor) from Xenopus laevis dermal melanophores. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19126–19133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lecoin L, Sakurai T, Ngo MT, Abe Y, Yanagisawa M, Le Douarin NM. Cloning and characterization of a novel endothelin receptor subtype in the avian class. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3024–3029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adachi M, Yang YY, Furuichi Y, Miyamoto C. Cloning and characterization of cDNA encoding human A-type endothelin receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;180:1265–1272. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasuda N, Tsukui T, Masuda K, Kawarai S, Ohmori K, et al. Cloning of cDNA encoding canine endothelin receptors and their expressions in normal tissues. J Vet Med Sci. 2005;67:1075–1079. doi: 10.1292/jvms.67.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shraga-Levine Z, Sokolovsky M. Functional coupling of G proteins to endothelin receptors is ligand and receptor subtype specific. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2000;20:305–317. doi: 10.1023/A:1007010125316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollock DM, Opgenorth TJ. Evidence for endothelin-induced renal vasoconstriction independent of ETA receptor activation. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:R222–R226. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.1.R222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollock DM. Contrasting pharmacological ETB receptor blockade with genetic ETB deficiency in renal responses to big ET-1. Physiol Genomics. 2001;6:39–43. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.6.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pollock DM, Pollock JS. Evidence for endothelin involvement in the response to high salt. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;281:F144–F150. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.1.F144. Pharmacological evidence that endothelin participates in salt-dependent blood pressure control

- 18.Haynes WG, Webb DJ. Contribution of endogenous generation of endothelin-1 to basal vascular tone. Lancet. 1994;344:852–854. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92827-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin P, Ninio D, Krum H. Effect of endothelin blockade on basal and stimulated forearm blood flow in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;39:821–824. doi: 10.1161/hy0302.105222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haynes WG, Ferro CJ, O'Kane KP, Somerville D, Lomax CC, Webb DJ. Systemic endothelin receptor blockade decreases peripheral vascular resistance and blood pressure in humans. Circulation. 1996;93:1860–1870. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.10.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callera GE, Touyz RM, Teixeira SA, Muscara MN, Carvalho MH, et al. ETA receptor blockade decreases vascular superoxide generation in DOCA-salt hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:811–817. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000088363.65943.6C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loomis ED, Sullivan JC, Osmond DA, Pollock DM, Pollock JS. Endothelin mediates superoxide production and vasoconstriction through activation of NADPH oxidase and uncoupled nitric-oxide synthase in the rat aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:1058–1064. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell FD, Molenaar P. The human heart endothelin system: ET-1 synthesis, storage, release and effect. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:353–359. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01524-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leite MF, Page E, Ambler SK. Regulation of ANP secretion by endothelin-1 in cultured atrial myocytes: desensitization and receptor subtype. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H2193–H2203. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.6.H2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skvorak JP, Nazian SJ, Dietz JR. Endothelin acts as a paracrine regulator of stretch-induced atrial natriuretic peptide release. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:R1093–R1098. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.5.R1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng TH, Shih NL, Chen CH, Lin H, Liu JC, et al. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in reactive oxygen species-mediated endothelin-1-induced beta-myosin heavy chain gene expression and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Biomed Sci. 2005;12:123–133. doi: 10.1007/s11373-004-8168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soma S, Takahashi H, Muramatsu M, Oka M, Fukuchi Y. Localization and distribution of endothelin receptor subtypes in pulmonary vasculature of normal and hypoxia-exposed rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:620–630. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.4.3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davie N, Haleen SJ, Upton PD, Polak JM, Yacoub MH, et al. ET(A) and ET(B) receptors modulate the proliferation of human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:398–405. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.3.2104059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohan DE. Endothelins: renal tubule synthesis and actions. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1996;23:337–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb02834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davenport AP, Nunez DJ, Brown MJ. Binding sites for 125I-labelled endothelin-1 in the kidneys: differential distribution in rat, pig and man demonstrated by using quantitative autoradiography. Clin Sci (Lond) 1989;77:129–131. doi: 10.1042/cs0770129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karet FE, Kuc RE, Davenport AP. Novel ligands BQ123 and BQ3020 characterize endothelin receptor subtypes ETA and ETB in human kidney. Kidney Int. 1993;44:36–42. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karet FE, Davenport AP. Comparative quantification of endothelin receptor mRNA in human kidney: new tools for direct investigation of human tissue. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;26 Suppl 3:S268–S271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nambi P, Pullen M, Wu HL, Aiyar N, Ohlstein EH, Edwards RM. Identification of endothelin receptor subtypes in human renal cortex and medulla using subtype-selective ligands. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1081–1086. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.3.1324149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garvin J, Sanders K. Endothelin inhibits fluid and bicarbonate transport in part by reducing Na+/K+ ATPase activity in the rat proximal straight tubule. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1991;2:976–982. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V25976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Jesus Ferreira MC, Bailly C. Luminal and basolateral endothelin inhibit chloride reabsorption in the mouse thick ascending limb via a Ca(2+)-independent pathway. J Physiol. 1997;505(Pt 3):749–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.749ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plato CF, Pollock DM, Garvin JL. Endothelin inhibits thick ascending limb chloride flux via ET(B) receptor-mediated NO release. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;279:F326–F333. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.2.F326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeidel ML, Brady HR, Kone BC, Gullans SR, Brenner BM. Endothelin, a peptide inhibitor of Na(+)-K(+)-ATPase in intact renaltubular epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:C1101–C1107. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.257.6.C1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kohan DE, Padilla E, Hughes AK. Endothelin B receptor mediates ET-1 effects on cAMP and PGE2 accumulation in rat IMCD. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:F670–F676. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.265.5.F670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ge Y, Stricklett PK, Hughes AK, Yanagisawa M, Kohan DE. Collecting duct-specific knockout of the endothelin A receptor alters renal vasopressin responsiveness, but not sodium excretion or blood pressure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F692–F698. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00100.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gurbanov K, Rubinstein I, Hoffman A, Abassi Z, Better OS, Winaver J. Differential regulation of renal regional blood flow by endothelin-1. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:F1166–F1172. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.6.F1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vassileva I, Mountain C, Pollock DM. Functional role of ETB receptors in the renal medulla. Hypertension. 2003;41:1359–1363. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000070958.39174.7E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gariepy CE, Ohuchi T, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Yanagisawa M. Salt-sensitive hypertension in endothelin-B receptor-deficient rats. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:925–933. doi: 10.1172/JCI8609. First evidence that ETB receptor dysfunction results in salt-sensitive hypertension

- 43. Ahn D, Ge Y, Stricklett PK, Gill P, Taylor D, et al. Collecting duct-specific knockout of endothelin-1 causes hypertension and sodium retention. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:504–511. doi: 10.1172/JCI21064. Evidence that renal tubular endothelin participates in blood pressure regulation

- 44.Fukuroda T, Fujikawa T, Ozaki S, Ishikawa K, Yano M, Nishikibe M. Clearance of circulating endothelin-1 by ETB receptors in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:1461–1465. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plumpton C, Ferro CJ, Haynes WG, Webb DJ, Davenport AP. The increase in human plasma immunoreactive endothelin but not big endothelin-1 or its C-terminal fragment induced by systemic administration of the endothelin antagonist TAK-044. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:311–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verhaar MC, Grahn AY, Van Weerdt AW, Honing ML, Morrison PJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic effects of ABT-627, an oral ETA selective endothelin antagonist, in humans. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49:562–573. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waggoner WG, Genova SL, Rash VA. Kinetic analyses demonstrate that the equilibrium assumption does not apply to [125I]endothelin-1 binding data. Life Sci. 1992;51:1869–1876. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90038-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takasuka T, Akiyama N, Horii I, Furuichi Y, Watanabe T. Different stability of ligand-receptor complex formed with two endothelin receptor species, ETA and ETB. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1992;111:748–753. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chun M, Lin HY, Henis YI, Lodish HF. Endothelin-induced endocytosis of cell surface ETA receptors. Endothelin remains intact and bound to the ETA receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10855–10860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oksche A, Boese G, Horstmeyer A, Furkert J, Beyermann M, et al. Late endosomal/lysosomal targeting and lack of recycling of the ligand-occupied endothelin B receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:1104–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bremnes T, Paasche JD, Mehlum A, Sandberg C, Bremnes B, Attramadal H. Regulation and intracellular trafficking pathways of the endothelin receptors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17596–17604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000142200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harada N, Himeno A, Shigematsu K, Sumikawa K, Niwa M. Endothelin-1 binding to endothelin receptors in the rat anterior pituitary gland: possible formation of an ETA-ETB receptor heterodimer. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2002;22:207–226. doi: 10.1023/A:1019822107048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hasselblatt M, Kamrowski-Kruck H, Jensen N, Schilling L, Kratzin H, et al. ETA and ETB receptor antagonists synergistically increase extracellular endothelin-1 levels in primary rat astrocyte cultures. Brain Res. 1998;785:253–261. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Inscho EW, Imig JD, Cook AK, Pollock DM. ETA and ETB receptors differentially modulate afferent and efferent arteriolar responses to endothelin. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:1019–1026. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jensen N, Hasselblatt M, Siren AL, Schilling L, Schmidt M, Ehrenreich H. ET(A) and ET(B) specific ligands synergistically antagonize endothelin-1 binding to an atypical endothelin receptor in primary rat astrocytes. J Neurochem. 1998;70:473–482. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70020473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ehrenreich H. The astrocytic endothelin system: toward solving a mystery focus on "distinct pharmacological properties of ET-1 and ET-3 on astroglial gap junctions and Ca(2+) signaling”". Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C614–C615. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.4.C614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor TA, Gariepy CE, Pollock DM, Pollock JS. Unique endothelin receptor binding in kidneys of ETB receptor deficient rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R674–R681. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00589.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gregan B, Jurgensen J, Papsdorf G, Furkert J, Schaefer M, et al. Ligand-dependent differences in the internalization of endothelin A and endothelin B receptor heterodimers. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27679–27687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gregan B, Schaefer M, Rosenthal W, Oksche A. Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Analysis Reveals the Existence of Endothelin-A and Endothelin-B Receptor Homodimers. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44:S30–S33. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000166218.35168.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.D'Alonzo GE, Barst RJ, Ayres SM, Bergofsky EH, Brundage BH, et al. Survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Results from a national prospective registry. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:343–349. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-5-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]