Abstract

Do you feel overwhelmed when attempting to treat battered women with ongoing safety concerns? Could battered women in shelters benefit from psychotherapy in addition to the case management they traditionally receive? What type of treatment would be most beneficial for battered women in shelters? Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is the most prevalent disorder associated with intimate partner violence (IPV). PTSD is associated with severe impairment and loss of resources which can severely impact a sheltered battered woman’s ability to establish long-term safety for herself and her children. Conequently, we have developed a new treatment for sheltered battered women with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Helping to Overcome PTSD through Empowerment (HOPE). HOPE is a short-term cognitive-behavioral treatment in a preliminary stage of development for battered women with PTSD in domestic violence shelters. It focuses on stabilization, safety, and empowerment and teaches women skills to manage their PTSD symptoms which may interfere with their ability to access important community resources and establish safety for themselves and their children. A case example utilizing HOPE is offered. Future directions and clinical applications are discussed.

Keywords: battered women, intimate partner violence, PTSD, cognitive-behavioral treatment, trauma

Violence against women is a significant social problem with research suggesting that as many as 22 to 29% of women report histories of intimate partner violence (IPV) (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). Furthermore, IPV remains the leading cause of injuries to women (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000) with the costs of IPV exceeding $5.8 billion annually (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2003). IPV has been linked to increased medical, psychological, and social morbidity (Browne, Salomon, & Bassuk, 1999; Dutton et al., 2006). In recognition of these significant difficulties, shelters for battered women, which provide physical safety, as well as emotional support and case management, are prevalent throughout the country.

Battered women suffer from a host of mental health problems and show higher rates of mental health difficulties than non-victims (Jones, Hughes, & Unterstaller, 2001), including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, and depression (Roberts, Lawrence, Williams, & Raphael, 1998; Zlotnick, Johnson, & Kohn, 2006). Additionally, the IPV itself, and the psychological sequelae of IPV impacts not only the woman, but her children (Holden, 1998). Despite these adverse effects of IPV on women and their children and the importance of treatment for this vulnerable population, the majority of published reports on the treatment of battered women offer theoretical models that are not empirically tested (e.g., Dutton, 1992; Walker, 1994). Research on the efficacy of interventions with battered women primarily evaluate advocacy services (Sullivan & Bybee, 1999), support groups (Tutty, Bidgood, & Rothery, 1996), or couples therapy (Schlee, Heyman, & O'Leary, 1998), which contributes little to our understanding of efficacious interventions for the traumatic effects of the abuse, such as PTSD.

The Importance of Treating PTSD in Battered Women

The diagnosis of PTSD and its associated features are most consistent with the collection of symptoms frequently found in battered women (Jones et al., 2001). A meta-analysis confirmed that PTSD is one of the most prevalent disorders in battered women (Golding, 1999). Furthermore, PTSD is a chronic condition, associated with severe morbidity and impairment. Therefore, the presence of significant PTSD symptoms can be potentially devastating for battered women. For example, employment dysfunction may contribute to a woman’s decision to return to unsafe environments because of financial dependence on their abuser.

Despite the significant psychosocial impairment of PTSD on battered women, only one treatment, to date, has been developed for and tested in battered women (Kubany et al., 2004). Kubany’s treatment was tested in a group of community women who were out of their relationship for at least one month, had no intent of reconciling, were considered safe, had not been physically or sexually abused or stalked for 30 days, and whose last incident of abuse occurred an average of five years prior. However, the experience of battered women in shelters can be different from community women in that battered women in shelters typically enter shelter directly after an acute battering incident, face ongoing safety concerns, and are at high risk for returning to the abusive relationship.

The Benefit of a Shelter-Based Treatment

Shelters are an integral resource for battered women with approximately 2,000 community-based shelter programs throughout the United States, providing emergency shelter to approximately 300,000 women and children each year (National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 2006). Shelter programs offer multiple services to battered women, including support, advocacy, social service referrals, transitional housing, legal resources, resources for children, and mental health and substance abuse referrals. Research suggests that battered women who seek more forms of help while in shelter report less re-victimization (Berk, Newton, & Berk, 1986), suggesting that offering treatment, a key resource that may make women more amendable and capable of utilizing other resources could be critical in enhancing the potential benefits of other shelter services. It appears that a prime time to intervene is when a woman is a resident of a battered woman’s shelter, considering that many battered women seek help from shelters and have instituted a change in their life.

Reasons to Treat PTSD in Battered Women in Shelters

Battered women in shelters are more likely to report a greater severity of abuse and related injury and exhibit a higher risk for PTSD than do battered women not in shelters (Jones et al., 2001; Saunders, 1994). Further, battered women, as a result of their PTSD, are likely to have experienced cycles of resource loss. Conservation of resource theory (Hobfoll & Lilly, 1993) hypothesizes a downward, bidirectional spiral between loss of resources and PTSD, in which resource loss contributes to the development of PTSD, which, in return, leads to a further loss of resources that can exacerbate PTSD and result in diminished functioning in multiple life spheres, including establishing their safety and independence from their abusers. Furthermore, PTSD symptoms appear to be associated with battered women’s risk of and degree of re-victimization (Perez & Johnson, 2008). Given that cessation of violence is necessary for recovery from its traumatic effects (Dutton, 1992; Herman, 1992), and that PTSD is related to risk of future re-victimization, it seems imperative to address PTSD and its associated features as soon as they are identified. Such intervention may improve battered women’s ability to effectively use resources that help maintain their and their children’s safety. However, few shelter programs offer shelter-based treatment of PTSD for battered women (Hughes & Jones, 2000).

Existing Treatments for PTSD and Battered Women in Domestic Violence Shelters

Treatments already exist for persons in the acute aftermath of trauma (Bryant, Harvey, Dang, Sackville, & Basten, 1998) and for people with PTSD (Foa et al., 2005; Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin, & Feuer, 2002), however these treatments do not address battered women’s ongoing threat of re-victimization and have not been tested in chronically traumatized populations (Solomon & Johnson, 2002). Further, most of these studies exclude women with recent domestic violence and do not collect or report on information on IPV and IPV-related PTSD. Battered women have multiple stressors with which to cope in addition to PTSD, including immediate safety concerns, mourning the loss of an intimate relationship, accessing resources to improve their safety, lack of social support, and concerns related to their children (Jones et al., 2001). Thus, the primary goal with this population is different in that the PTSD needs to be addressed in a context that is consistent with battered women’s current needs and will not interfere with their ability to effectively use resources and establish physical safety.

Although exposure-based treatments are recommended as the first line treatment for PTSD, exposure to recent domestic violence or trauma is typically contraindicated in existing PTSD treatments. Battered women in shelters have multiple concerns that can lead to increased anxiety (e.g., homelessness, risk for future victimization), and overwhelming anxiety can impede the efficacy of exposure techniques (Jaycox & Foa, 1996). Furthermore, many of the symptoms of PTSD experienced by battered women represent fear reactions to the threat of ongoing victimization (Foa, Cascardi, Zoellner, & Feeny, 2000). Given these concerns and the recentness of their victimization, exposure interventions may not only be ineffective, but may re-traumatize women causing them to decompensate to a degree that further limits their ability to establish safety (Herman, 1992). Therefore, traditional PTSD treatments that incorporate exposure are contraindicated, as habituation to feared stimuli may increase their risk for further victimization. The only empirically supported treatment to date, for battered women with PTSD (Kubany et al., 2004), incorporates exposure techniques and therefore is contraindicated for battered women in domestic violence shelters.

Using Cognitive-Behavioral Theories to Direct Treatment with Sheltered Battered Women

Cognitive-behavioral theories propose that trauma survivors process the traumatic event based on their pre-existing beliefs about the self, others and the world (Brewin, Dalgleish, & Joseph, 1996; Ehlers & Clark, 2000; McCann, Sakheim, & Abrahamson, 1988). McCann and colleagues propose that these specific cognitions relate to beliefs about safety, trust, power/control, esteem, and intimacy (McCann et al., 1988). These cognitions have been hypothesized to underlie PTSD, and have been addressed directly in the treatment of PTSD (Resick et al., 2002). Unsuccessful information processing occurs when people are unable to assimilate the information with their prior belief systems, and this can lead to the symptoms characteristic of and associated with PTSD (Brewin et al., 1996). Although exposure to the traumatic memory is contraindicated for sheltered battered women, other integral elements of cognitive-behavioral treatments are relevant to battered women, including modification of cognitive appraisals of the trauma and/or it’s sequelae that maintain a sense of threat and PTSD symptoms reduction of use of maladaptive coping strategies that exacerbate PTSD symptoms and prevent successful information processing (Ehlers & Clark, 2000).

Focusing on Stabilization

Since more emphasis needs to be placed on stabilization than what is typically done in treatment of PTSD, a cognitive-behavioral treatment approach within a stage approach also appears imperative for battered women living in shelters. Herman (1992) developed a multistage model of recovery that addresses the complicated treatment needs of recently battered women: (1) establishing safety, (2) remembrance and mourning, and (3) reconnection. According to this model, the most urgent clinical need in the treatment of PTSD is the establishment of physical and emotional safety. Battered women come to shelters to establish physical safety and to access resources to improve the quality of battered women’s lives. Thus, a first-stage, present-centered treatment, emphasizing goals of safety, self-care, and protection, and the exchange of information on PTSD symptoms (Herman, 1992) meshes with the treatment needs of battered women in shelters. This stage approach encourages empowerment and is consistent with the existing theoretical literature on the treatment of battered women (Dutton, 1992). Theoretically, this treatment approach might improve battered women’s ability to utilize the resources available to them in the shelter.

In this paper, we provide a summary of our work so far in developing a new treatment for PTSD in battered women in shelters, Helping to Overcome PTSD through Empowerment (HOPE). In an effort to assist clinicians in treating a very challenging population, we provide a summary of the literature and research findings on which HOPE is based, as well as a case presentation illustrating HOPE in a battered women’s shelter.

Developing HOPE

In developing HOPE we have conducted a series of studies including (1) focus groups with over 30 battered women, (2) a series of cross-sectional studies with over 200 sheltered battered women (see Table 1), and (3) have treated over 50 women in either our open trial with HOPE or our ongoing randomized clinical trial. First, we investigated treatment utilization over the past 6 months in a subgroup of 164 African-American and White shelter residents (Johnson & Zlotnick, 2007). Results indicated that while 69% met criteria for IPV-related PTSD, only 22% of women received some type of psychotherapy and 40% received any type of mental health treatment over the last 6 months. Next, we investigated the impact of PTSD symptoms on battered women’s psychiatric and social morbidity in a sample of 177 residents of a domestic violence shelter (Johnson, Zlotnick, & Perez, in press). Results revealed that when controlling for the effects of IPV, PTSD severity significantly related to a higher degree of comorbidity, more psychiatric severity, poorer social adjustment, less effective use of community resources, and greater loss of personal and social resources. Furthermore, PTSD severity significantly mediated the relationships between IPV-severity and psychiatric severity and resource loss. Taken together, these two studies highlight the importance of providing treatment of IPV-related PTSD to sheltered battered women, especially given that a majority of the women have not received appropriate treatment and experienced a loss of critical resources.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of sheltered battered women (N = 227)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 111 | 48.9 |

| Caucasian | 93 | 41.0 |

| Other race | 23 | 10.1 |

| Hispanic | 19 | 8.4 |

| Highest Education Obtained | ||

| Less than high school | 56 | 24.7 |

| High school/GED | 71 | 31.3 |

| Completed some college | 79 | 34.8 |

| Graduated from college | 21 | 9.2 |

| On Public Assistance | 135 | 59.5 |

| Employed | 59 | 26.0 |

| Children in Shelter | 84 | 37.0 |

| Cohabitated with or married to abuser | 174 | 76.7 |

| Resource Needs* | ||

| Housing | 216 | 95.2 |

| Education | 162 | 71.4 |

| Transportation | 161 | 70.9 |

| Employment | 162 | 71.4 |

| Legal | 137 | 60.4 |

| Physical Health | 165 | 72.7 |

| Social Support | 149 | 65.6 |

| Financial | 162 | 71.4 |

| Home Services | 149 | 65.6 |

| Child Care | 61 | 26.9 |

| Current Psychiatric Disorders | ||

| IPV-related PTSD | 155 | 68.3 |

| Major Depression | 107 | 47.1 |

| Bipolar Disorder | 25 | 11.0 |

| Substance Use Disorder | 26 | 11.5 |

| Other Anxiety Disorder | 117 | 51.5 |

| Prior lifetime IPV | 164 | 72.2 |

| Prior lifetime trauma other than IPV | 222 | 97.8 |

Note. Data based on participant report on whether since shelter admittance they “needed to work on” a specific resource in the Effectiveness in Obtaining Resources Scale ( Sullivan & Bybee, 1999).

We also completed a series of focus groups with sheltered battered women to inform treatment development. Participants were asked to comment on the emotional difficulties they experienced, on the type of treatment they believed would have been useful, and on their responses to a rationale and description of HOPE. The women described a variety of mental health concerns at the time they were shelter residents, including feelings of helplessness, intrusive symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, avoidance of abuse related stimuli, intense fear, low self-esteem, depression, difficulties coping with stressors, and relationship concerns. Generally speaking, these women described a pattern of unhealthy relationships and concern over breaking the cycle of violence for both them and their children. In general, women responded favorably to the HOPE rationale and indicated that they would want to attend HOPE and that they believed it would be helpful. Women also emphasized the need for individual therapy, given the supportive milieu already provided in shelter. Many women suggested that treatment during shelter might provide the additional support women need to establish long-term safety for themselves and their children. These focus groups provided some initial support of the acceptability of HOPE.

HOPE for Battered Women with PTSD in Domestic Violence Shelters

Incorporating the literature on IPV, PTSD, and cognitive-behavioral theories, HOPE is a present-centered, first-stage, 9–12 session, individual cognitive-behavioral treatment that addresses the cognitive, behavioral, and interpersonal dysfunction associated with PTSD in battered women. HOPE was specifically designed for battered women with ongoing safety concerns and our experience thus far suggests that HOPE is unsuitable for women with significant pathology (i.e., suicidiality, a bipolor or psychotic disorder, and/or active substance dependence) who need more intensive and specialized treatment.

HOPE addresses McCann et al’s (1988) five schematic areas of dysfunction (i.e., safety, trust, power/control, esteem, intimacy). Additionally, HOPE adopts a multicultural approach in that the therapist is encouraged to address how cultural differences between the therapist and client may impact the therapeutic relationship as well as to explore ways in which clients’ cultural background has influenced their experience of abuse, PTSD, and resource utilization. HOPE is also delivered in-shelter, encourages collaboration with shelter staff, incorporates individual goals, and prioritizes immediate safety needs and empowerment and choice throughout treatment. HOPE includes a hierarchy of target behaviors that guide the content of treatment: (1) immediate physical and emotional risks, (2) PTSD symptoms, behaviors, and cognitions that interfere with achieving shelter and treatment goals, (3) PTSD symptoms and behavioral and cognitive patterns that interfere with quality of life, and (4) post-shelter goals and safety. Also, since sheltered battered women experience many competing demands and can be difficult to engage in therapy, engagement strategies were incorporated into early sessions (e.g., helping the client articulate their expectations for therapy; defining for the client how therapy can help her achieve her personal goals).

Throughout HOPE, women are encouraged to identify the aspects of any threats to their physical and emotional safety that are within their control and to skillfully address these threats. Also during the first two sessions, women identify and prioritize their personal goals, and these goals are used to individualize treatment and to further engage and empower women in the treatment (e.g., prioritize needs; determine relevant optional modules, tying personal goals to HOPE strategies). A safety plan is established by the third session and safety is evaluated at the beginning of every session to determine if further safety planning is required. Clients are provided with an “empowerment tool-box” that includes an exhaustive list of strategies that can help women (1) establish safety and empowerment, (2) manage symptoms, and (3) improve their relationships. Clients are encouraged to use this toolbox to help them better cope with their current stressors and symptoms. Each of the skills is then addressed more specifically in one of the ten core modules (see Table 2). Accomplishments are assigned between sessions to assist women in applying the empowerment tools to their daily lives. The first 4–5 sessions of HOPE typically focus on psychoeducation regarding IPV, PTSD, and safety planning, as well as in teaching women skills that empower them to establish their independence and to make informed choices. Then, while still maintaining the HOPE hierarchy of target behaviors, the last 6–7 sessions of HOPE emphasize established cognitive-behavioral skills to manage PTSD and its associated features. Table 2 summarizes the content of the primary HOPE modules. Optional modules also exist that address some of the co-occurring problems frequently found in battered women (i.e., crisis management, PTSD and substance use, grounding, nightmares and grief).

Table 2.

Overview of HOPE

| Domains Addressed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modules | Schema * | Cognitive | Behavioral | Interpersonal |

| Establishing Safety and Empowerment | ||||

| 1. Engagement Strategies | X | X | ||

| 2. Knowledge is Power: Psychoeducation re Abuse and PTSD |

Power/Control | X | X | |

| 3. Safety Planning | Safety | X | X | |

| 4. Empowering Yourself and Establishing Trust in Relationships |

Power/Control Trust |

X | X | X |

| Managing PTSD with Safe Coping | ||||

| 5. Rethinking Victim Thinking into Survivor Thinking |

Esteem | X | ||

| 6. Coping with Triggers Day and Night | Safety | X | X | |

| 7. Self-Soothing and Relaxation | Safety | X | X | |

| Improving Relationships | ||||

| 8. Establishing Boundaries | Intimacy | X | X | X |

| 9. Improving Relationships by Managing Anger |

Intimacy | X | X | X |

| 10. Termination/Establishing Long- term Support |

Safety | X | ||

Note. McCann et al’s (1988)five schematic areas of dysfunction

Issues in Delivering PTSD Treatment in Battered Women’s Shelters

HOPE was designed to be delivered in domestic violence shelters and to complement the supportive milieu, case management, and advocacy services traditionally offered in shelters. Our research suggests that battered women access a variety of residential facilities in addition to battered women’s shelters. Of the 227 women we have assessed, 37% reported prior use of homeless shelters and 22% prior stays in half-way houses. These facilities present very different issues for the delivery of treatment for IPV-related PTSD and research is still needed to determine what type of modifications might be required to successfully deliver HOPE in these other shelter environments.

Battered Women who seek shelter present with a variety of issues in addition to their recent IPV (see Table 1). Almost all of the women we have assessed to date have prior trauma histories and a majority present with multiple psychiatric diagnoses. Further, battered women have numerous resource needs including, but not limited to housing, employment, education, transportation, legal issues, health problems, and lack of childcare. Finally, many battered women’s shelters have strict guidelines regarding compliance with case plans and shelter rules (e.g., no alcohol or drug use), thus residents have extremely busy schedules and risk being prematurely exited from the shelter if they are not compliant with rules. Given battered women’s ongoing safety concerns and transportation issues, we designed HOPE to be delivered within the shelter setting. Further, we recommend the following additional considerations when offering HOPE in domestic violence shelters: (1) therapists require flexibility regarding scheduling and canceling appointments, (2) childcare must be available during sessions, (3) coordinate treatment plan with shelter case manager (e.g., inquiring about any concerns shelter staff may have regarding the resident and educating case manager on how PTSD may be interfering with residents’ performance on the case plan), and (4) in an effort to facilitate residents’ trust in the therapist and improve the client-therapist relationship, the therapist should not have any role in managing other shelter concerns and should not be required to report violation of shelter rules unless they pose an immediate threat to resident or staff safety.

For research purposes, the current version of HOPE was designed to be administered exclusively in shelter. We wanted to represent what we thought was most consistent with the realities of offering treatment in a shelter setting, especially considering that in most cases women typically don’t continue to have access to shelter resources after they leave. However, we also recognize that all shelters have different policies and procedures (e.g., some limit the length of stay). The frequency of HOPE sessions can easily be increased if it needs to be administered in a shorter time frame. Given these issues, it is extremely important that the client understand these time constraints and for the HOPE therapist to have an adequate system of referral for women who continue to require treatment after they leave shelter. Further, if a client leaves shelter suddenly, we recommend offering a termination session and to never terminate therapy if it is clinically contra-indicated (e.g., the client is in crisis).

Case Study: An Example of HOPE

We present the story of a woman who participated in HOPE to clarify the components of HOPE. Her case also highlights many of the complexities of working with battered women in shelters and the importance that the treating clinician approach therapy in a manner that is consistent with the client’s needs.

Jane1, a 29 year old married woman of Eastern European decent, was in the shelter for 17 days with her two children at the start of treatment. Jane reported that her husband first became abusive when she was pregnant. She described her husband as primarily emotionally and verbally abusive with several incidents of physical abuse throughout her 5 ½ years of marriage. Jane sought shelter after a physical altercation with her husband that led her to fear for her safety. This was her first attempt to leave her husband, and she never previously sought any assistance related to her martial abuse or any type of mental health services. Jane presented with significant IPV-related PTSD symptoms and no Axis I comorbidity.

Jane attended 12 bi-weekly sessions of HOPE over 7 weeks. Her first two sessions focused on increasing safety and breaking the cycle of abuse, psycho-education of abuse and PTSD, connecting her abuse and current difficulties, establishing treatment goals, and creating a treatment plan that included decreasing PTSD and associated symptoms, increasing self-esteem, and asking for help and setting boundaries when needed. Jane was introduced to the “empowerment tool-box” and encouraged to implement these tools between sessions.

Jane’s 3rd and 4th sessions focused on safety planning. At this time, Jane considered dropping the civil protective order (CPO) she had obtained towards her husband. Consistent with her cultural beliefs, she expressed concern that the CPO was interfering with her husband’s ability to maintain a relationship with their two children. Additionally, Jane expressed a strong desire to reconcile with her husband, but only if her husband “truly changed.” Therapy focused on assisting Jane in evaluating her safety, making a decision about the CPO, and identifying specific behaviors she expected from her husband before reconciling. Educational materials regarding power and control and trust were then applied to Jane’s decision-making and safety planning. Additionally, per the HOPE hierarchy, Jane’s safety, need for a CPO, and desire to reconcile with her husband were evaluated and discussed throughout the remainder of treatment.

Session 5 focused more specifically on power and control issues, especially targeting Jane’s goal to assert her personal power in positive ways by asking for help and setting boundaries in both her personal relationships and in utilizing shelter resources. Jane was encouraged to begin identifying aspects of her situation that were under her control and to use empowerment tools to help manage those issues. For example, Jane had difficulty asking her case manager or shelter staff for assistance when in her best interest (e.g., when she had difficulty setting up her children’s visitation with their father). Therapy focused on helping Jane apply her new interpersonal skills and work with her case manager on finding options that would be in compliance with the court ruling for supervised visitation. Further, Jane’s disruptive thoughts that she was somehow “weak” if she asked others for help and that other people’s needs superseded her own were gently challenged.

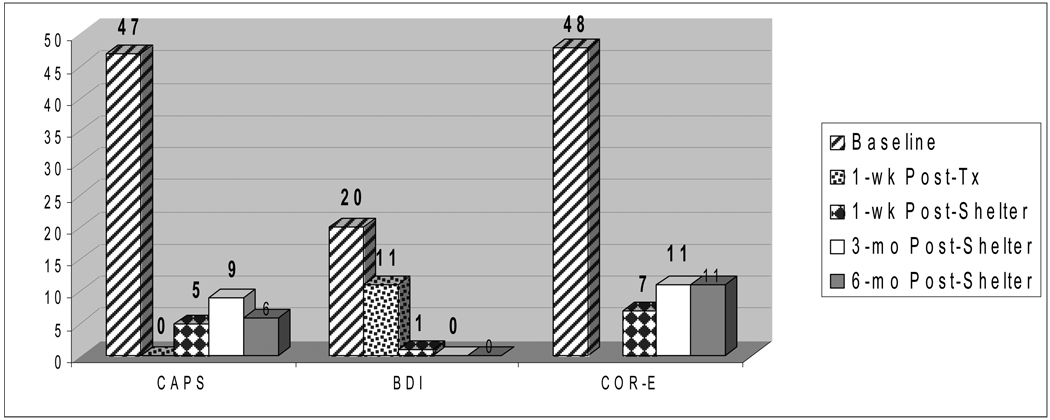

Sessions 6–12 incorporated traditional cognitive-behavioral techniques to assist Jane in managing her PTSD and associated symptoms. She was taught how to identify and challenge the disruptive thinking patterns resulting from her abuse and PTSD, as well as skills to manage her triggers, improve her sleep, self-soothe, and to safely express her anger. Throughout this time, her progress on her shelter and treatment goals was monitored. By session 12, Jane had her name on all housing lists, obtained childcare for her children, and was studying for a placement exam for the educational program she wanted to attend. Jane also expressed more self-confidence and reported improved ability and comfort in setting boundaries. Additionally, Jane decided to drop the CPO for her husband and continued to articulate a plan to reconcile once her husband displayed consistent behavioral change. At this time, long-term goals and a safety plan for after she left shelter were identified. Jane left shelter 6 weeks after completing HOPE. She reported that she had enrolled in school and was frustrated with the shelter environment. She had no success finding independent housing and decided to return to her husband. She continued to deny any further abuse at her 6-month follow-up and articulated a solid safety plan. At her post-treatment assessments, Jane no longer met diagnostic criteria for PTSD and showed improvement on her severity of PTSD symptoms, depression, and personal and social resource loss (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Jane’s PTSD severity (Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) (Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001)), depression severity (Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck, 1961)) and personal and social resource loss (Conservation of Resource-Evaluation) (COR-E) (Hobfoll & Lilly, 1993)) from baseline to 6 months after discharge from shelter. The COR-E was not administered at 1-wk post-treatment. Chart legend is in same order as chart bars. In psychosocial intervention research CAPS reduction ranges from 19–100% with a median of 50% (Weathers et al., 2001). For BDI scores below 9 are in normal range (Beck et al., 1961). No clinical cut-off scores exist for the COR-E.

HOPE: The Next Stage

HOPE was recently evaluated in an open trial of 18 battered women in which women received an average of 7 sessions while in shelter (Johnson & Zlotnick, 2006). Results of intent-to-treat and completer analyses indicate that women who received HOPE displayed significant and clinically meaningful decreases in PTSD symptoms, depressive symptoms, loss of personal and social resources, as well as in their degree of social impairment. HOPE participants also displayed a significant increase in their effective use of community resources and reported a high level of satisfaction with the program. These gains were maintained up to six months after women left shelter. Future research, with more rigorous methodology is ongoing that will help determine if HOPE is associated with significant improvement beyond standard shelter services.

Although extremely preliminary, our research thus far, suggests that HOPE has some potential in the treatment of PTSD in sheltered battered women. However, as demonstrated in this case, a large portion of women leave shelter prematurely, have ongoing contact with their abuser, and face multiple stressors after they leave shelter. Jane reported leaving the shelter and returning to her husband out of frustration and difficulties in obtaining safe and affordable housing. She also had a strong desire to keep her family in tact and felt that she “owed” it to her husband and children to give the marriage one more try. Consistent with Jane’s case, interim analyses we conducted with the first 43 participants of our ongoing randomized trial of HOPE found that 83% of women either reported further domestic violence, contact with their abuser, and/ or another significant trauma after leaving the shelter. Furthermore, many women do not stay in shelter long enough to complete HOPE. In our research, residents’ length of shelter stay ranged from 5 to 365 days (M = 61.16, SD = 55.41). Thus, we recently began asking women who completed HOPE if they wanted additional sessions after leaving shelter, and all so far (n = 11) have reported a desire for additional sessions. Given these findings, we are currently working to expand HOPE to include sessions after women leave the shelter. Such a treatment approach would potentially provide Jane the added support she needs to evaluate her ongoing safety, reinforce her newly acquired skills, continue working towards her goals, and prevent relapse of PTSD symptoms that could further interfere with her ability to evaluate her safety and to access sources of support.

Implications for Practice

Although further research is needed to test the efficacy of HOPE and caution is warranted when drawing any conclusions about HOPE, our work so far suggests that battered women from shelters can benefit from therapy and that their PTSD symptoms can be targeted during this period of crisis and instability. However, treatment at this time must be flexible and meet the unique needs of sheltered battered women. Further, it is imperative that the therapist’s expectations be realistic and consistent with the goals battered women have when seeking shelter. For example, treatment needs to focus on safety, reducing PTSD symptoms, and assisting the woman in obtaining the skills required to improve her resource utilization during and after she leaves shelter, rather than on encouraging women to leave or have no contact with her abuser. Thus, much of therapy at this stage can be more appropriately viewed as setting the foundation for future changes. Further, it is important that shelter treatment assists the woman in identifying and accessing her transitional needs (e.g., obtaining post-shelter safe and affordable housing and a source of income) which typically requires the therapist to work closely with the shelter case manager.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this manuscript was supported by NIMH grant K23 MH067648 and CTSTS pilot funds. We would like to thank Cynthia Cluster, Keri Pinna, Sara Perez, Brigette Shy, Kirsten DeLambo, Holly Harris, Kristen Walter, and the Battered Women’s Shelter of Summit and Medina Counties for their assistance in these projects.

Biographies

DAWN M. JOHNSON received her Ph.D. in counseling psychology from the University of Kentucky. She is clinic coordinator and full-time faculty at the Summa-Kent State Center for the Treatment and Study of Traumatic Stress (CTSTS) in Akron, OH. Her research interests include PTSD and interpersonal violence with an emphasis on the treatment of battered women with PTSD.

CARON ZLOTNICK received her Ph.D. in clinical psychology from the University of Rhode Island. She is Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. She is Director of Research for Women’s Behavioral Health at Women and Infants Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island and is also affiliated with Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island. The main focus of her research includes trauma, PTSD, and postpartum depression.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at http://www.apa.org/journals/pro/

This client provided written consent to have her case presented in a manuscript. Identifying information has been changed in order to protect the client’s anonymity.

Contributor Information

Dawn M. Johnson, Summa-Kent State Center for the Treatment and Study of Traumatic Stress

Caron Zlotnick, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

References

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk RA, Newton PJ, Berk SF. What a difference a day makes: An empirical study of the impact of shelters for battered women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1986;48:481–490. [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Dalgleish R, Joseph S. A dual representation theory of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Review. 1996;103:670–686. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne A, Salomon A, Bassuk SS. The impact of recent partner violence on poor women's capacity to maintain work. Violence Against Women. 1999;5:393–426. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Harvey AG, Dang ST, Sackville T, Basten C. Treatment of acute stress disorder: A comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:862–866. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA. Empowering and healing the battered woman: A model for assessment and intervention. NY: Springer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Green BL, Kaltman SI, Roesch DM, Zeffiro TA, Krause ED. Intimate Partner Violence, PTSD, and Adverse Health Outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:955–968. doi: 10.1177/0886260506289178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Clark DM. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2000;38:319–345. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Cascardi M, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC. Psychological and environmental factors associated with partner violence. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2000;1:67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahill SP, Rauch SAM, Riggs DS, Feeny NC, et al. Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: Outcome at academic and community clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:953–964. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14:99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Herman JL. Trauma and Recovery. New York: Basic Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Lilly RS. Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:128–148. [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW. Introduction: The development of research into another consequence of family violence. In: Holden GW, Geffner R, Jouriles EN, editors. Children exposed to marital violence: Theory, research and applied issues. Washington, D C: American Psychological Association; 1998. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes MJ, Jones L. Women, domestic violence, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Family Therapy. 2000;27:125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, Foa EB. Obstacles in implementing exposure therapy for PTSD: Case discussions and practical solutions. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 1996;3:176–184. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Zlotnick C. A cognitive-behavioral treatment for battered women with PTSD in shelters: Findings from a pilot study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:559–564. doi: 10.1002/jts.20148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Zlotnick C. Utilization of mental health treatment and other services in sheltered battered women. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1595–1597. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Zlotnick C, Perez S. The relative contribution of abuse severity and PTSD severity on the psychiatric and social morbidity of battered women in shelters: Behavior Therapy. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.08.003. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Hughes M, Unterstaller U. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in victims of domestic violence: A review of the research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2001;2:99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Hill EE, Owens JA, Iannce-Spencer C, McCaig MA, Tremayne KJ, et al. Cognitive trauma therapy for battered women with PTSD (CTT-BW) Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:3–18. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann L, Sakheim DK, Abrahamson DJ. Trauma and victimization: A model of psychological adaptation. Counseling Psychologist. 1988;39:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Atlanta, GA: Costs of intimate partner violence against women in the United States: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. [Retrieved 8/24/06, 2006];2006 http://www.ncadv.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Perez S, Johnson DM. Trauma-related symptomatology interferes with battered women's ability to establish long-term safety. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:635–651. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, Astin MC, Feuer CA. A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:867–879. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts GL, Lawrence JM, Williams GM, Raphael B. The impact of domestic violence on women's mental health. Australian New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 1998;22:796–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1998.tb01496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders DG. Posttraumatic stress symptom profiles of battered women: A comparison of survivors in two settings. Violence and Victims. 1994;9:31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlee KA, Heyman RE, O'Leary KD. Group treatment for spouse abuse: Are women with PTSD appropriate participants? Journal of Family Violence. 1998;13:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon SD, Johnson DM. Psychosocial treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: A practice-friendly review of outcome research. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;58:947–959. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan CM, Bybee DI. Reducing violence using community-based advocacy for women with abusive partners. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:43–53. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extant, nature, and consequences of intimate partner violence (NCJ-154348) Washington, DC: Department of Defense; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tutty LM, Bidgood BA, Rothery MA. Evaluating the effect of group process and client variables in support groups for battered women. Research in Social Work Practice. 1996;6:308–324. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JRT. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Johnson DM, Kohn R. Intimate Partner Violence and Long-Term Psychosocial Functioning in a National Sample of American Women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:262–275. doi: 10.1177/0886260505282564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]