Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a major respiratory pathogen in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients, facilitates infection by other opportunistic pathogens. Burkholderia cenocepacia, which normally infects adolescent patients, encounters alginate elaborated by mucoid P. aeruginosa. To determine whether P. aeruginosa alginate facilitates B. cenocepacia infection in mice, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator knockout mice were infected with B. cenocepacia strain BC7 suspended in either phosphate-buffered saline (BC7/PBS) or P. aeruginosa alginate (BC7/alginate), and the pulmonary bacterial load and inflammation were monitored. Mice infected with BC7/PBS cleared all of the bacteria within 3 days, and inflammation was resolved by day 5. In contrast, mice infected with BC7/alginate showed persistence of bacteria and increased cytokine levels for up to 7 days. Histological examination of the lungs indicated that there was moderate to severe inflammation and pneumonic consolidation in isolated areas at 5 and 7 days postinfection in the BC7/alginate group. Further, alginate decreased phagocytosis of B. cenocepacia by professional phagocytes both in vivo and in vitro. P. aeruginosa alginate also reduced the proinflammatory responses of CF airway epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages to B. cenocepacia infection. The observed effects are specific to P. aeruginosa alginate, because enzymatically degraded alginate or other polyuronic acids did not facilitate bacterial persistence. These observations suggest that P. aeruginosa alginate may facilitate B. cenocepacia infection by interfering with host innate defense mechanisms.

Respiratory failure due to lung infection is the major cause of mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. CF airways are colonized by more than one opportunistic bacterial pathogen, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a major pathogen. The other opportunistic bacterial pathogens that are frequently isolated from CF airways include Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, the Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (7). Most individuals with CF experience a characteristic age-related pattern of pulmonary colonization and intermittent exacerbations involving H. influenzae and S. aureus, followed by P. aeruginosa (4, 5). Similarly, accumulating evidence suggests that P. aeruginosa can promote colonization by less commonly observed bacteria, such as S. maltophilia, Achromobacter xylosoxidans, and Mycobacterium abscessus (43). P. aeruginosa has also been implicated in promoting BCC pathogenesis by increasing the adherence of BCC to respiratory epithelial cells and upregulating the expression of BCC virulence factors (17, 31, 32).

Chronic P. aeruginosa infections are often associated with a mucoid phenotype due to the production of large quantities of the acidic exopolysaccharide alginate (5). Alginate is an important extracellular virulence factor and has been shown to impair host innate defenses related to phagocytes (1, 13, 15, 18, 26, 30). In CF airways, P. aeruginosa is found in the airway lumen, and hence one may expect large amounts of alginate in airways along with host products. Sputum samples from CF patients have been shown to contain 50 to 200 μg/ml alginate (23, 30). In fact, it is likely that there are much higher concentrations of alginate in CF airways, as sputum samples are mixed with host secretions and hence the concentration of alginate may be underestimated. Since BCC infection generally occurs in patients who have been chronically colonized with mucoid P. aeruginosa, we hypothesized that alginate in the airways may prevent detection of BCC by phagocytes and facilitate colonization of CF lungs by BCC. To test this hypothesis, we infected gut-corrected CF mice with Burkholderia cenocepacia strain BC7 suspended in either phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (BC7/PBS), P. aeruginosa alginate (BC7/alginate), or enzymatically degraded alginate (BC7/ED-alginate) and examined the persistence of bacteria and the associated lung inflammation. We also examined the effects of alginate on phagocytosis of B. cenocepacia by macrophages and neutrophils and the proinflammatory responses of airway epithelial cells to B. cenocepacia infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and growth conditions.

B. cenocepacia strains BC7 and BC45 were isolated from the sputum of CF patients and have been described previously (36, 37). Burkholderia multivorans and S. maltophilia were kindly provided by J. LiPuma (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). Nontypeable H. influenzae was provided by T. Murphy (University of Buffalo, Buffalo, NY) and has been described previously (38). B. cepacia ATCC 25416 was purchased from American Type Tissue Culture (Manassas, VA). A clinical strain of mucoid P. aeruginosa, isolate NH57338A, was provided by N. Hoffmann (University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark). All bacteria were maintained as glycerol stocks at −80°C, and bacteria used for infection were prepared as described previously (35) and suspended in PBS or purified Pseudomonas alginate at the concentration required. The actual concentration of bacteria in a suspension was determined by plating. For measurement of phagocytosis, bacteria were labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) as described previously (36).

Isolation and purification of alginate.

P. aeruginosa alginate was isolated from a single clinical strain of mucoid P. aeruginosa, isolate NH57388A, as described previously (11, 29). Purified alginate was treated with DNase I (10 U/ml) and RNase A (10 μg/ml) to remove contaminating RNA and DNA. Contaminating lipopolysaccharides in the alginate were removed by using an endotrap red kit (Lonza, Walkersville, MD). Finally, the alginate was precipitated and dissolved in sterile endotoxin-free PBS at a concentration of 8 mg/ml, based on the uronic acid content as measured by the carbazol method (2). The lipopolysaccharide content was determined by using an endpoint chromogenic Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay kit (Lonza) and was found to be <0.1 endotoxin unit/mg of alginate. The alginate preparation was treated with alginate lyase for 6 h at 37°C (Sigma Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, MO) to enzymatically degrade the alginate polymer into small oligomers to obtain ED-alginate, which was used as a control for alginate.

Infection of animals.

Ten- to 12-week-old strain Cftrtm1/Unc-TgN(FABPCFTR)iJaw/J homozygous cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) knockout mice were purchased from the Case Western Reserve University Animal Resource Center (Cleveland, OH). C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River. All mice were maintained in a specific-pathogen-free barrier facility in microisolator cages throughout the experiment. All procedures performed with the mice were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Michigan. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazene (41) and sham infected with 50 μl of PBS or PBS containing 180 μg of alginate or ED-alginate or were infected with BC7 (1 × 106 to 5 × 106 CFU) suspended in either PBS (BC7/PBS), P. aeruginosa alginate (BC7/alginate), or ED-alginate (BC7/ED-alginate) by the intratracheal route. In some experiments mice were infected with BC7 suspended in low-melting-point agarose, polygalacturonic acid, or seaweed alginate (Sigma Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, MO) at a concentration similar to that of P. aeruginosa alginate. Mice were sacrificed at predetermined times, as indicated below, by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital.

BAL.

Mice were sacrificed at predetermined times, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed as described previously (24, 33).

Bacterial load.

Lungs and spleens were harvested aseptically and homogenized in sterile PBS. Tenfold serial dilutions of lung or spleen homogenates were plated on B. cepacia isolation agar (BCSA) (9) to determine the bacterial load.

Analysis of lung cytokines and myeloperoxidase activity.

Lung homogenates were prepared in the presence of protease inhibitors and centrifuged, and the supernatants were used for cytokine analysis with a bioplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Lung myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was quantified as described previously (42).

Histopathology.

Lungs were inflation fixed via the trachea with 10% formalin overnight and embedded in paraffin. Lung sections (thickness, 5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

CF airway epithelial cells and infection.

Immortalized CF bronchial epithelial cells (IB3 cells) and C38 cells (IB3 cells expressing wild-type CFTR) (45) were kindly provided by P. Zeitlin (Johns Hopkins Medical Institute, Baltimore, MD) and were grown in LHC-8 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 5% serum as described previously (24). Cells were infected with BC7 at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 in the presence or absence of alginate and incubated for 6 h, and the interleukin-8 (IL-8) in the culture supernatants was measured by an ELISA (R&D Systems).

Phagocytosis assay.

Mouse alveolar macrophage cell line CRL-2019 MH-S (American Type Tissue Culture, Manassas, VA) was maintained in RPMI medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and l-glutamine. Phagocytosis of bacteria by alveolar macrophages was determined as described previously (25). Cells pretreated with cytochalasin D (2 μg/ml) were used to confirm that the fluorescent bacteria detected were intracellular bacteria and not extracellular bacteria. Numbers of intracellular bacteria were determined either by confocal microscopy or by flow cytometry.

To determine the effect of alginate on phagocytosis of bacteria in vivo, mice were infected with BC7/PBS or BC7/alginate, and BAL was performed 2 h postinfection. Cytospin preparations of BAL cells were prepared, stained with DiffQuik (Dade Behring, Newark, DE), and incubated with trypan blue to quench the fluorescence of extracellular bacteria. Neutrophils and macrophages were identified based on the shape of the nucleus and the size of the cells. Neutrophils contain a multilobar nucleus, and macrophages are relatively large cells with a U-shaped or rounded nucleus and could be differentiated from other BAL cells readily. The first 300 macrophages or neutrophils were examined for the presence of intracellular bacteria, and the results were expressed as the percentage of cells positive for whole intracellular bacteria.

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed below as means and standard deviations or as ranges of data with geometric means. Data were analyzed by using SigmaStat statistical software (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA). To compare groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey-Kramer post hoc analysis or ANOVA on Ranks with Dunn's post hoc analysis was performed, as appropriate. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Alginate facilitates B. cenocepacia persistence in mice.

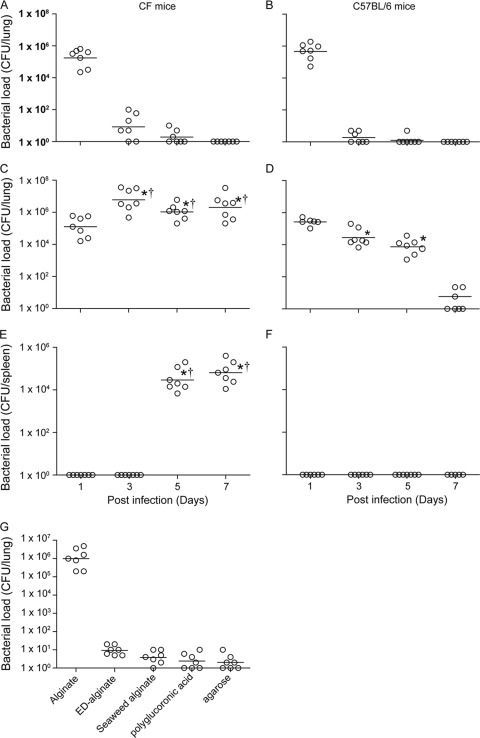

Gut-corrected chow-fed CFTR knockout (CF) mice or C57BL/6 mice were infected with BC7/PBS or BC7/alginate, and the lung bacterial load was determined at 1, 3, 5, or 7 days postinfection. Mice that were sham infected with PBS or alginate alone were used as controls, and as expected, none of these mice showed bacteria in their lungs (data not shown). Mice infected with BC7/PBS cleared all bacteria within 3 days irrespective of the mouse genotype (Fig. 1A and 1B). In contrast, CF mice infected with BC7/alginate and C57BL/6 mice infected with BC7/alginate showed persistence of bacteria for up to 7 days and 5 days, respectively (Fig. 1C and 1D). CF mice infected with BC7/alginate also showed bacteria in the spleen at 5 and 7 days postinfection, indicating that there was dissemination of bacteria (Fig. 1E and 1F). Approximately 30% of CF mice infected with BC7/alginate died during the course of infection, suggesting that CF mice are more vulnerable to infection. Due to increased mortality and severe inflammation in CF mice infected with BC7/alginate, the experiment was terminated at 7 days postinfection. These results suggest that suspension of BC7 in a P. aeruginosa alginate solution increases the capacity of bacteria to persist in both CF and normal mice. Since CF mice showed prolonged bacterial persistence and inflammation, we performed subsequent experiments with CF mice unless otherwise indicated.

FIG. 1.

P. aeruginosa alginate increases BC7 persistence in mice. Mice infected with BC7/PBS (A and B) or BC7/alginate (C to F) were sacrificed at predetermined time points, and 10-fold serial dilutions of lung (A to D) and spleen (E and F) homogenates were plated on BCSA to determine the bacterial load. Also, CF mice were infected with BC7 suspended in alginate, ED-alginate, seaweed alginate, polygalacturonic acid, or agarose, and the bacterial density in the lungs was measured at 5 days postinfection (G). The open circles indicate individual mice, and the bars indicate the geometric means calculated for three independent experiments with a total of seven mice per group (*, different from the BC7/PBS group at the same time point; †, significantly different from BC7/alginate-infected C57BL/6 mice at the same time point [P ≤ 0.05, as determined by ANOVA on Ranks with Dunn's post hoc analysis]).

To confirm the role of alginate in facilitating bacterial persistence, CF mice were infected with BC7 suspended in alginate enzymatically degraded with alginate lyase (ED-alginate), and the lung bacterial load was determined 5 days postinfection. Mice infected with BC7/alginate consistently showed bacteria in their lungs, as described above. Mice in the BC7/ED-alginate group showed very few bacteria in their lungs (Fig. 1G) compared to mice in the BC7/alginate group. These results confirmed that alginate, but not other contaminating factors present in the preparation, is responsible for promoting bacterial persistence.

To determine whether other polysaccharides could promote bacterial persistence like that seen with P. aeruginosa alginate, mice were infected with BC7 suspended in 0.15% seaweed alginate (BC7/seaweed alginate), polygalacturonic acid (BC7/polygalacturonic acid), or low-melting-point agarose (BC7/agarose), and the pulmonary bacterial load was measured at 5 days postinfection. The concentration of seaweed alginate and polygalacturonic acid used was based on the uronic acid content. As observed for the BC7/PBS or BC7/ED-alginate group, mice infected with BC7/seaweed alginate, BC7/polygalacturonic acid, or BC7/agarose showed a negligible number of bacteria in their lungs, indicating that the observed effect was specific for P. aeruginosa alginate (Fig. 1G). Based on these results, we used BC7 suspended in either PBS (control), P. aeruginosa alginate, or ED-alginate (control for alginate) in subsequent experiments.

Bacterial persistence corresponds to lung inflammation.

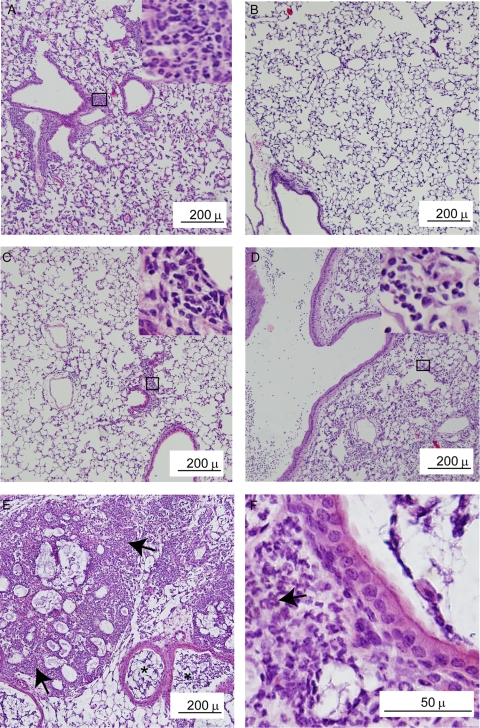

Histological evaluation of lung sections from CF mice treated with PBS did not reveal inflammation at any of the time points examined (data not shown). At 1 day postinfection, mice infected with BC7/PBS showed moderate lung inflammation with accumulation of neutrophils, particularly in peribronchiolar and perivascular areas (Fig. 2A), and there was mild or no inflammation at 5 days postinfection (Fig. 2B). Similar changes in inflammation were observed for mice infected with BC7/ED-alginate (data not shown). Mice treated with alginate alone showed very mild inflammation at 1 day postinfection, which resolved completely by day 5 (data not shown). In contrast, CF mice infected with BC7/alginate showed mild inflammation on day 1 (Fig. 2C). At 5 days postinfection, we observed moderate to severe neutrophilic inflammation (Fig. 2D), which progressed to pneumonic consolidation and tissue destruction by day 7 (Fig. 2E and 2F).

FIG. 2.

Mice infected with BC7/alginate show severe inflammation. Paraffin lung sections were prepared for mice infected with BC7/PBS (A and B) or BC7/alginate (C to F) at day 1 (A and C), day 5 (B and D), and day 7 (E and F) postinfection and stained with H&E. The insets in panels A, C, and D are magnifications of the areas in boxes to show neutrophil accumulation. Arrows in panels E and F point to areas of inflammation. The images are representative of the results for three individual animals at each time point.

The MPO activity (a surrogate marker for neutrophils) in the lungs of sham-infected animals (mice given PBS or alginate alone) was similar at all time points and hence was considered the baseline in comparisons of the MPO activities of BC7-infected animals. Mice in the BC7/PBS and BC7/ED-alginate groups showed peak MPO activity at 1 day postinfection, and the activity gradually decreased and returned to the basal levels by day 7 (Fig. 3A). The mice given BC7/alginate, however, showed less MPO activity at 1 day postinfection than the mice in the BC7/PBS or BC7/ED-alginate group, whose activity peaked at 5 days and persisted for up to 7 days postinfection. These observations were consistent with the histological observations described above.

FIG. 3.

Levels of inflammatory markers are increased in mice infected with BC7/P. aeruginosa alginate. CF mice infected with BC7/PBS, BC7/alginate, or BC7/ED-alginate were sacrificed at 1, 3, 5, or 7 days postinfection. MPO activity (A) was determined using whole-lung homogenates and was expressed as the fold increase compared with corresponding sham-treated animals. IL-1β (B), TNF-α (C), MIP-2 (D), and KC (E) levels in lung homogenates were measured by ELISA, and the results were corrected for the cytokine levels observed in corresponding sham-treated controls. The data are the means and standard deviations calculated from three independent experiments with a total of seven mice per group (*, different from BC7/PBS and BC7/ED-alginate groups at the same time point [P ≤ 0.05, as determined by ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post hoc analysis]).

BC7-infected mice showed significant increases in the levels of all of the proinflammatory cytokines measured (IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], KC, MIP-2) compared to the corresponding sham-infected groups at 1 day postinfection (Fig. 3B to 3E). However, at this time point, mice in the BC7/PBS or BC7/ED-alginate group had significantly higher levels of all cytokines than mice in the BC7/alginate group. While the cytokine levels for the BC7/PBS and BC7/ED-alginate groups returned to the basal levels by day 3 or 5, for the BC7/alginate group there were sustained increases in the levels of all of the cytokines measured up to day 7.

Alginate interferes with phagocytosis.

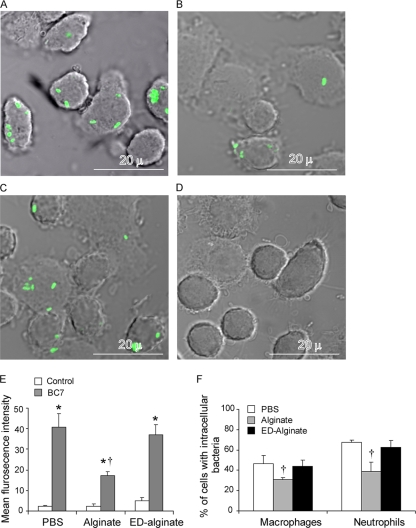

Alginate has been shown to prevent detection of P. aeruginosa by phagocytes (16). To assess whether alginate similarly protects BC7 from phagocytes, murine alveolar macrophages were incubated with FITC-labeled BC7 suspended in medium, medium containing alginate, or medium containing ED-alginate; then the extracellular fluorescence was quenched, and cells were examined for the presence of intracellular bacteria by confocal microscopy. Alveolar macrophages incubated with FITC-labeled BC7 suspended in alginate (Fig. 4B) contained fewer intracellular bacteria than cells incubated with FITC-labeled BC7 suspended in medium (Fig. 4A) or ED-alginate (Fig. 4C). Cytochalasin D inhibits phagocytosis, and as expected, cells pretreated with cytochalasin D did not contain fluorescent bacteria (Fig. 4D). These results indicate that the fluorescing bacteria observed in cells in the absence of cytochalasin D truly were intracellular bacteria. Quantification of phagocytosis by flow cytometry indicated that there were significantly fewer bacteria in the macrophages incubated with BC7/alginate than in the cells incubated with BC7/medium or BC7/ED-alginate (Fig. 4E), confirming our microscopic observations.

FIG. 4.

P. aeruginosa alginate attenuates phagocytosis in vitro and in vivo. (A to C) Alveolar macrophages were incubated with FITC-labeled BC7 suspended in medium (A), alginate (B), or ED-alginate (C) for 90 min. Unbound bacteria were removed, the fluorescence of extracellular bacteria was quenched, and cells were examined using a confocal microscope. (D) Alveolar macrophages were pretreated with cytochalasin D for 30 min, incubated with FITC-labeled BC7 suspended in medium, and examined for the presence of intracellular bacteria. Green indicates intracellular bacteria, and the images are representative of three independent experiments. (E) In some experiments, cells were detached from the wells and subjected to flow cytometry, and the results were expressed as the mean fluorescence intensity. (F) CF mice were infected with FITC-labeled BC7 suspended in either PBS, alginate, or ED-alginate, BAL was performed, fluorescence of extracellular bacteria was quenched, and the percentages of macrophages and neutrophils with intracellular bacteria were determined by fluorescence microscopy. The data are the means and standard deviations of four independent experiments performed in duplicate or triplicate (*, different from the corresponding untreated control [P = <0.05]; †, different from the BC7/PBS and BC7/ED-alginate groups [P ≤ 0.05, as determined by ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post hoc analysis]).

To examine whether alginate protects BC7 from phagocytes in vivo, animals were infected with FITC-labeled bacteria suspended in PBS, P. aeruginosa alginate, or ED-alginate, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells were collected 2 h postinfection, and the numbers of intracellular bacteria in neutrophils and macrophages were determined by microscopy. Both neutrophils and macrophages from mice infected with BC7/alginate contained fewer bacteria than cells from mice infected with BC7/PBS or BC7/ED-alginate (Fig. 4F). These results suggest that alginate interferes with ingestion of BC7 by both neutrophils and macrophages in vivo.

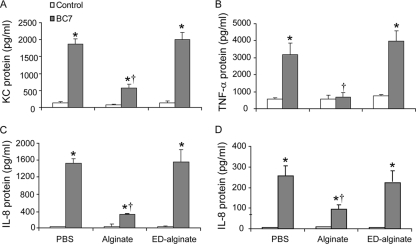

Alginate decreases proinflammatory responses in vitro.

To examine whether the reduction in phagocytosis is accompanied by an attenuated proinflammatory response, mouse alveolar macrophages, human CF bronchial epithelial cells (IB3 cells), and IB3 cells expressing wild-type CFTR (C38 cells) were incubated with bacteria suspended in medium, alginate, or ED-alginate, and cytokine levels were measured after 30 min of incubation for macrophages or after 6 h of incubation for airway epithelial cells. Macrophages or airway epithelial cells incubated with alginate or ED-alginate alone did not show an increase in cytokine production (Fig. 5). All three cell types expressed significant amounts of cytokines upon incubation with bacteria compared to the corresponding sham controls. Cells incubated with bacteria suspended in alginate showed low levels of cytokines compared to cells incubated with bacteria alone or with bacteria suspended in ED-alginate. These results suggest that alginate interferes with the normal proinflammatory response to bacterial infection in both macrophages and airway epithelial cells, likely reflecting the decrease in the timely clearance of infecting organisms.

FIG. 5.

P. aeruginosa alginate decreases proinflammatory responses of alveolar macrophages and human airway epithelial cells in vitro. Murine alveolar macrophages (A and B), IB3 cells (human CF bronchial epithelial cells) (C), or C38 cells (IB3 cells corrected for CFTR) (D) were incubated with BC7 in the presence or absence of alginate for 30 min (for macrophages) or 6 h (for epithelial cells), and cytokine levels in the media were measured. The data are the means and standard deviations of four independent experiments performed in triplicate (*, different from the corresponding untreated control [P = <0.05]; †, different from the BC7/PBS group [P ≤ 0.05, as determined by ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post hoc analysis]).

Presence of alginate in the lungs facilitates BC7 persistence.

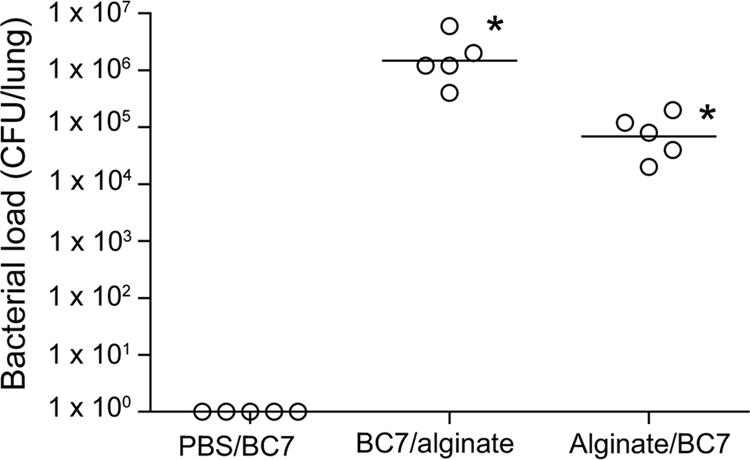

In CF lungs, BC7 encounters alginate only after it enters the airways; hence, we examined whether alginate present in the lungs can facilitate BC7 persistence. First alginate and then BC7 suspended in PBS (alginate/BC7) were instilled into lungs of CF mice by the intratracheal route, and the bacterial load was determined after 5 days. Control mice, which were treated with PBS instead of alginate (PBS/BC7), cleared all bacteria from their lungs, as observed previously. However, mice in the alginate/BC7 group showed bacteria in their lungs after 5 days (Fig. 6), indicating that the presence of alginate in the lungs facilitates BC7 persistence. Interestingly, the load was 1 log lower than that in the mice infected with BC7 suspended in alginate (BC7/alginate), suggesting that bacteria which do not interact with alginate may be killed readily by phagocytes.

FIG. 6.

Prior administration of alginate enhances BC7 persistence in mice. CF mice were treated with BC7 mixed with alginate (BC7/alginate), with PBS and then with BC7 suspended in PBS (PBS/BC7), or with alginate and then with BC7 suspended in PBS (Alginate/BC7). The pulmonary bacterial load was determined at 5 days postinfection. The open circles indicate results for individual animals, and the bars indicate geometric means calculated from two independent experiments.

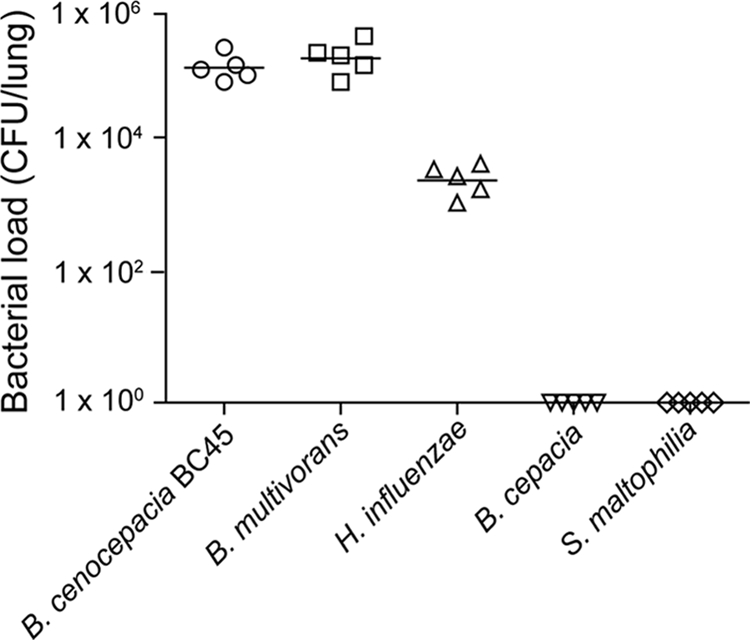

Alginate-facilitated bacterial persistence depends on the capacity of bacteria to cause infection.

To examine whether alginate facilitates the persistence of bacteria other than B. cenocepacia BC7, mice were infected with B. cepacia, B. multivorans, B. cenocepacia BC45, nontypeable H. influenzae, or S. maltophilia suspended in either PBS or alginate, and the pulmonary bacterial load was determined 5 days postinfection. None of the mice infected with bacteria suspended in PBS showed bacteria in their lungs (data not shown). On the other hand, in mice infected with bacteria suspended in alginate there was variable bacterial persistence depending on the species of bacteria (Fig. 7). While B. multivorans, B. cenocepacia BC45, and nontypeable H. influenzae persisted in the lungs, B. cepacia and S. maltophilia were cleared from the lungs. Mice infected with B. multivorans and B. cenocepacia BC45 had 2 logs more bacteria in their lungs than the mice infected with nontypeable H. influenzae. These results indicate that not all species of bacteria that infect CF patients are protected from the innate immune system by alginate and that the observed persistence of bacteria may also depend on the capacity of bacteria to successfully colonize the lungs.

FIG. 7.

P. aeruginosa alginate-facilitated bacterial persistence depends on the bacterial species. CF mice were infected with B. cepacia, B. multivorans, B. cenocepacia BC45, nontypeable H. influenzae, or S. maltophilia suspended in P. aeruginosa alginate. The bacterial load in the lungs was measured at 3 days postinfection. The symbols indicate results for individual animals, and the bars indicate geometric means calculated from two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrated that alginate, a virulence factor produced by P. aeruginosa with a mucoid phenotype, interferes with host innate immune defenses and facilitates infection by other opportunistic pathogens, including B. cenocepacia. Although a small number of CF patients harbor B. cenocepacia, a member of the BCC complex, the clinical prognosis is worse for these patients than for patients colonized with P. aeruginosa alone (40). Approximately one-third of the B. cenocepacia-infected CF patients show rapid clinical deterioration and develop fatal pneumonia and bacteremia known as “cepacia syndrome” (10). Infection with B. cenocepacia often occurs in adolescent or adult CF patients who already have been chronically colonized with mucoid P. aeruginosa, suggesting that mucoid P. aeruginosa may facilitate B. cenocepacia infection. In fact, it has been shown that exoproducts of P. aeruginosa modify the airway epithelial cell surface in a way that facilitates adherence of BCC (32). Addition of spent culture medium supernatants or acyl homoserine lactone extracts of P. aeruginosa to growth media enhances the production of protease, lipase, and siderophores by BCC (17, 31). Here we show that the alginate polymer produced by mucoid P. aeruginosa facilitates persistence of B. cenocepacia in the lungs of CF mice by protecting the bacteria from phagocytes and reducing the inflammatory response during the initial phase of infection. Further, we demonstrate that while normal mice cleared bacteria by day 7, CF mice developed severe inflammation and pneumonic consolidation and that there was dissemination of bacteria, resulting in death of 30% of the mice 7 days after infection.

P. aeruginosa alginate appears to be unique in facilitating persistence of bacteria in mice; suspension of bacteria in other acidic polysaccharides or agarose did not promote persistence of B. cenocepacia. Previously, seaweed alginate and agarose have been used to create chronic lung infections in lungs of CF and normal mice (3, 8, 20-22); however, this required mechanical entrapment of bacteria in the polymerized beads of seaweed alginate or agarose rather than suspension of bacteria in solution, which was used in the present study. Further, P. aeruginosa alginate-facilitated persistence also appears to depend on the capacity of bacteria to colonize CF lungs successfully as P. aeruginosa alginate did not promote colonization by B. cepacia or S. maltophilia.

The alginate used in this study had a uronic acid content of 87.1%, indicating that components other than alginate may also interfere with the host innate defense mechanisms. Recently, N-(3-oxo-dodecanoyl)homoserine lactone (C12) produced by P. aeruginosa was shown to impair NF-κB-regulated functions in macrophages exposed either to Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) or TLR4 ligands or to whole bacteria (12). The fact that enzymatically degraded alginate, which retained essentially all of the components except the intact alginate polymer, failed to facilitate bacterial persistence in vivo and to interfere with phagocytic function suggests that other components in the alginate preparation do not contribute to this effect.

In mice susceptible to P. aeruginosa lung infection (strain DBA/2) there is a delay in the inflammatory response and initiation of bacterial clearance compared to the response of resistant mice (strain BALB/c) (19). Following intratracheal infection, resistant mice showed a rapid influx of neutrophils (within 24 h) that was associated with clearance of bacteria. In contrast, Wilson et al. (44) showed that, despite a similar neutrophil influx in both susceptible DBA/2 and resistant C57BL/6 mice during the initial phase of infection, only resistant mice cleared the bacteria, suggesting that there is a requirement for other host factors. Further, these authors showed that, although macrophages from susceptible mice are initially more phagocytic than C57BL/6 macrophages, they are defective for clearing or controlling bacterial colonization, indicating that rather than delaying the neutrophilic response, defective macrophages contribute to the susceptibility of DBA/2 mice to bacterial infection. In the current study, we found that compared to mice infected with BC7/PBS or BC7/ED-alginate, mice infected with BC7/alginate showed less neutrophilic inflammation and MPO activity at 24 h postinfection and also that there were fewer bacteria in macrophages and neutrophils, indicating that P. aeruginosa alginate interferes with neutrophil infiltration as well as phagocytosis. This is probably due to the capacity of alginate to alter the surface characteristics of bacteria, thereby rendering them resistant to phagocytosis by neutrophils and macrophages (1, 13, 16, 18, 26).

Mucoid P. aeruginosa produces copious amounts of alginate. Therefore, it is conceivable that CF airways are enriched in alginate, although the alginate may be bound to a mucoid P. aeruginosa biofilm matrix. However, the recovery of alginate in CF sputum (23, 30) suggests that alginate may be available for interaction with other bacteria. Since administration of alginate to mouse airways prior to B. cenocepacia infection also promoted the persistence of bacteria, it is possible that alginate can interact with B. cenocepacia in vivo and protect it from innate immune defenses. Our results also suggest that CF mice are more vulnerable to B. cenocepacia infection as these mice develop severe lung inflammation and pneumonic consolidation and show dissemination of bacteria to the spleen, with 30% of the mice dying by 7 days after infection. We speculate that this sensitivity of CF mice may be due to a combination of the protective effect of alginate and defective killing of bacteria by neutrophils. It has been shown that CFTR-dependent chloride anion transport is essential for neutrophil MPO to produce hypochlorous acid and bactericidal activity (27, 28). Recently, polymorphisms in the Ifdr1 gene were detected in a cohort of CF patients, and experimental evidence suggested that IFDR1 regulates neutrophil effector function and is required for bacterial clearance (6). Deficiencies in clearing of bacteria by neutrophils may contribute to the observed severity of lung disease in CF mice.

A delay in the initiation of bacterial clearance may increase the virulence of infecting organisms, especially the organisms that are capable of invading mucosal cells and resisting normal endocytic clearance mechanisms. B. cenocepacia and B. multivorans can evade the normal endocytic pathway, reside and replicate within epithelial cells and macrophages (14, 34, 39), and thus benefit from the presence of P. aeruginosa alginate in the airway lumen of CF patients. Consistent with this, we observed that B. cenocepacia BC7, which was isolated from a patient who succumbed to “cepacia syndrome” (36, 37), persisted and caused pneumonic consolidation and bacteremia and also death in 30% of the infected CF mice in the presence of P. aeruginosa alginate. In summary, we demonstrate here that alginate produced by P. aeruginosa facilitates infection by other bacteria by interfering with the initial host innate immune responses and also that bacteria capable of causing persistent infection benefit from the presence of P. aeruginosa alginate.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Hoffmann (University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark) for providing mucoid P. aeruginosa and A. van Heeckeren (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH) for providing CFTR knockout mice [strain Cftrtm1/Unc-TgN(FABPCFTR)iJaw/J].

This work was supported by grants SAJJAN06I0, SAJJAN08G0, HL089772, and GOLDBE07G0 from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

Editor: B. A. McCormick

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 January 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cabral, D. A., B. A. Loh, and D. P. Speert. 1987. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa resists nonopsonic phagocytosis by human neutrophils and macrophages. Pediatr. Res. 22:429-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cesaretti, M., E. Luppi, F. Maccari, and N. Volpi. 2003. A 96-well assay for uronic acid carbazole reaction. Carbohydr. Polym. 54:59-61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cieri, M. V., N. Mayer-Hamblett, A. Griffith, and J. L. Burns. 2002. Correlation between an in vitro invasion assay and a murine model of Burkholderia cepacia lung infection. Infect. Immun. 70:1081-1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilligan, P. H. 1991. Microbiology of airway disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:35-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Govan, J. R., and V. Deretic. 1996. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol. Rev. 60:539-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gu, Y., I. T. Harley, L. B. Henderson, B. J. Aronow, I. Vietor, L. A. Huber, J. B. Harley, J. R. Kilpatrick, C. D. Langefeld, A. H. Williams, A. G. Jegga, J. Chen, M. Wills-Karp, S. H. Arshad, S. L. Ewart, C. L. Thio, L. M. Flick, M. D. Filippi, H. L. Grimes, M. L. Drumm, G. R. Cutting, M. R. Knowles, and C. L. Karp. 2009. Identification of IFRD1 as a modifier gene for cystic fibrosis lung disease. Nature 458:1039-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison, F. 2007. Microbial ecology of the cystic fibrosis lung. Microbiology 153:917-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heeckeren, A., R. Walenga, M. W. Konstan, T. Bonfield, P. B. Davis, and T. Ferkol. 1997. Excessive inflammatory response of cystic fibrosis mice to bronchopulmonary infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Clin. Invest. 100:2810-2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henry, D. A., M. E. Campbell, J. J. LiPuma, and D. P. Speert. 1997. Identification of Burkholderia cepacia isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis and use of a simple new selective medium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:614-619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isles, A., I. Maclusky, M. Corey, R. Gold, C. Prober, P. Fleming, and H. Levison. 1984. Pseudomonas cepacia infection in cystic fibrosis: an emerging problem. J. Pediatr. 104:206-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashef, N., Q. Behzdian-Jejad, S. Najar-Peerayen, K. Mousavi-Hosseini, M. Moazeni, H. Rezvan, and B. Adibi-Motlagh. 2005. Preliminary investigation on the isolation of alginate produced by mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ann. Microbiol. 55:279-282. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kravchenko, V. V., G. F. Kaufmann, J. C. Mathison, D. A. Scott, A. Z. Katz, D. C. Grauer, M. Lehmann, M. M. Meijler, K. D. Janda, and R. J. Ulevitch. 2008. Modulation of gene expression via disruption of NF-kappaB signaling by a bacterial small molecule. Science 321:259-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krieg, D. P., R. J. Helmke, V. F. German, and J. A. Mangos. 1988. Resistance of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa to nonopsonic phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages in vitro. Infect. Immun. 56:3173-3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamothe, J., K. K. Huynh, S. Grinstein, and M. A. Valvano. 2007. Intracellular survival of Burkholderia cenocepacia in macrophages is associated with a delay in the maturation of bacteria-containing vacuoles. Cell. Microbiol. 9:40-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Learn, D. B., E. P. Brestel, and S. Seetharama. 1987. Hypochlorite scavenging by Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate. Infect. Immun. 55:1813-1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leid, J. G., C. J. Willson, M. E. Shirtliff, D. J. Hassett, M. R. Parsek, and A. K. Jeffers. 2005. The exopolysaccharide alginate protects Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm bacteria from IFN-gamma-mediated macrophage killing. J. Immunol. 175:7512-7518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKenney, D., K. E. Brown, and D. G. Allison. 1995. Influence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoproducts on virulence factor production in Burkholderia cepacia: evidence of interspecies communication. J. Bacteriol. 177:6989-6992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meshulam, T., N. Obedeanu, D. Merzbach, and J. D. Sobel. 1984. Phagocytosis of mucoid and nonmucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 32:151-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morissette, C., C. Francoeur, C. Darmond-Zwaig, and F. Gervais. 1996. Lung phagocyte bactericidal function in strains of mice resistant and susceptible to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 64:4984-4992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morissette, C., E. Skamene, and F. Gervais. 1995. Endobronchial inflammation following Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in resistant and susceptible strains of mice. Infect. Immun. 63:1718-1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moser, C., S. Kjaergaard, T. Pressler, A. Kharazmi, C. Koch, and N. Hoiby. 2000. The immune response to chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection in cystic fibrosis patients is predominantly of the Th2 type. APMIS 108:329-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moser, C., M. Van Gennip, T. Bjarnsholt, P. O. Jensen, B. Lee, H. P. Hougen, H. Calum, O. Ciofu, M. Givskov, S. Molin, and N. Hoiby. 2009. Novel experimental Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection model mimicking long-term host-pathogen interactions in cystic fibrosis. APMIS 117:95-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mrsny, R. J., B. A. Lazazzera, A. L. Daugherty, N. L. Schiller, and T. W. Patapoff. 1994. Addition of a bacterial alginate lyase to purulent CF sputum in vitro can result in the disruption of alginate and modification of sputum viscoelasticity. Pulm. Pharmacol. 7:357-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newcomb, D. C., U. S. Sajjan, D. R. Nagarkar, Q. Wang, S. Nanua, Y. Zhou, C. L. McHenry, K. T. Hennrick, W. C. Tsai, J. K. Bentley, N. W. Lukacs, S. L. Johnston, and M. B. Hershenson. 2008. Human rhinovirus 1B exposure induces phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent airway inflammation in mice. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 177:1111-1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ojielo, C. I., K. Cooke, P. Mancuso, T. J. Standiford, K. M. Olkiewicz, S. Clouthier, L. Corrion, M. N. Ballinger, G. B. Toews, R. Paine III, and B. B. Moore. 2003. Defective phagocytosis and clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the lung following bone marrow transplantation. J. Immunol. 171:4416-4424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliver, A. M., and D. M. Weir. 1985. The effect of Pseudomonas alginate on rat alveolar macrophage phagocytosis and bacterial opsonization. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 59:190-196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Painter, R. G., R. W. Bonvillain, V. G. Valentine, G. A. Lombard, S. G. LaPlace, W. M. Nauseef, and G. Wang. 2008. The role of chloride anion and CFTR in killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by normal and CF neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 83:1345-1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Painter, R. G., V. G. Valentine, N. A. Lanson, Jr., K. Leidal, Q. Zhang, G. Lombard, C. Thompson, A. Viswanathan, W. M. Nauseef, G. Wang, and G. Wang. 2006. CFTR expression in human neutrophils and the phagolysosomal chlorination defect in cystic fibrosis. Biochemistry 45:10260-10269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pedersen, S. S., F. Espersen, N. Hoiby, and G. H. Shand. 1989. Purification, characterization, and immunological cross-reactivity of alginates produced by mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:691-699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedersen, S. S., A. Kharazmi, F. Espersen, and N. Hoiby. 1990. Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate in cystic fibrosis sputum and the inflammatory response. Infect. Immun. 58:3363-3368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riedel, K., M. Hentzer, O. Geisenberger, B. Huber, A. Steidle, H. Wu, N. Hoiby, M. Givskov, S. Molin, and L. Eberl. 2001. N-acylhomoserine-lactone-mediated communication between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia in mixed biofilms. Microbiology 147:3249-3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saiman, L., G. Cacalano, and A. Prince. 1990. Pseudomonas cepacia adherence to respiratory epithelial cells is enhanced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 58:2578-2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sajjan, U., M. Corey, A. Humar, E. Tullis, E. Cutz, C. Ackerley, and J. Forstner. 2001. Immunolocalisation of Burkholderia cepacia in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:535-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sajjan, U., S. Keshavjee, and J. Forstner. 2004. Responses of well-differentiated airway epithelial cell cultures from healthy donors and patients with cystic fibrosis to Burkholderia cenocepacia infection. Infect. Immun. 72:4188-4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sajjan, U., G. Thanassoulis, V. Cherapanov, A. Lu, C. Sjolin, B. Steer, Y. J. Wu, O. D. Rotstein, G. Kent, C. McKerlie, J. Forstner, and G. P. Downey. 2001. Enhanced susceptibility to pulmonary infection with Burkholderia cepacia in Cftr(−/−) mice. Infect. Immun. 69:5138-5150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sajjan, U., Y. Wu, G. Kent, and J. Forstner. 2000. Preferential adherence of cable-piliated Burkholderia cepacia to respiratory epithelia of CF knockout mice and human cystic fibrosis lung explants. J. Med. Microbiol. 49:875-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sajjan, U. S., M. Corey, M. A. Karmali, and J. F. Forstner. 1992. Binding of Pseudomonas cepacia to normal human intestinal mucin and respiratory mucin from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 89:648-656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sajjan, U. S., Y. Jia, D. C. Newcomb, J. K. Bentley, N. W. Lukacs, J. J. LiPuma, and M. B. Hershenson. 2006. H. influenzae potentiates airway epithelial cell responses to rhinovirus by increasing ICAM-1 and TLR3 expression. FASEB J. 20:2121-2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sajjan, U. S., J. H. Yang, M. B. Hershenson, and J. J. LiPuma. 2006. Intracellular trafficking and replication of Burkholderia cenocepacia in human cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 8:1456-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Speert, D. P. 2002. Advances in Burkholderia cepacia complex. Paediatr Respir. Rev. 3:230-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsai, W. C., M. B. Hershenson, Y. Zhou, and U. Sajjan. 2009. Azithromycin increases survival and reduces lung inflammation in cystic fibrosis mice. Inflamm. Res. 58:491-501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsai, W. C., R. M. Strieter, J. M. Wilkowski, K. A. Bucknell, M. D. Burdick, S. A. Lira, and T. J. Standiford. 1998. Lung-specific transgenic expression of KC enhances resistance to Klebsiella pneumoniae in mice. J. Immunol. 161:2435-2440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wahab, A. A., I. A. Janahi, M. M. Marafia, and S. El-Shafie. 2004. Microbiological identification in cystic fibrosis patients with CFTR I1234V mutation. J. Trop. Pediatr. 50:229-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson, K. R., J. M. Napper, J. Denvir, V. E. Sollars, and H. D. Yu. 2007. Defect in early lung defence against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in DBA/2 mice is associated with acute inflammatory lung injury and reduced bactericidal activity in naive macrophages. Microbiology 153:968-979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeitlin, P. L., L. Lu, J. Rhim, G. Cutting, G. Stetten, K. A. Kieffer, R. Craig, and W. B. Guggino. 1991. A cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial cell line: immortalization by adeno-12-SV40 infection. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 4:313-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]