Abstract

The autoinducer-3 (AI-3)/epinephrine (Epi)/norepinephrine (NE) interkingdom signaling system mediates chemical communication between bacteria and their mammalian hosts. The three signals are sensed by the QseC histidine kinase (HK) sensor. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is a pathogen that uses HKs to sense its environment and regulate virulence. Salmonella serovar Typhimurium invades epithelial cells and survives within macrophages. Invasion of epithelial cells is mediated by the type III secretion system (T3SS) encoded in Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1), while macrophage survival and systemic disease are mediated by the T3SS encoded in SPI-2. Here we show that QseC plays an important role in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium pathogenicity. A qseC mutant was impaired in flagellar motility, in invasion of epithelial cells, and in survival within macrophages and was attenuated for systemic infection in 129x1/SvJ mice. QseC acts globally, regulating expression of genes within SPI-1 and SPI-2 in vitro and in vivo (during infection of mice). Additionally, dopamine β-hydroxylase knockout (Dbh−/−) mice that do not produce Epi or NE showed different susceptibility to Salmonella serovar Typhimurium infection than wild-type mice. These data suggest that the AI-3/Epi/NE signaling system is a key factor during Salmonella serovar Typhimurium pathogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Elucidation of the role of this interkingdom signaling system in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium should contribute to a better understanding of the complex interplay between the pathogen and the host during infection.

Prokaryotes and eukaryotes achieve cell-to-cell signaling utilizing chemical signals. The signaling systems allow intra- and interspecies and intra- and interkingdom communication (48). The autoinducer-3 (AI-3)/epinephrine (Epi)/norepinephrine (NE) interkingdom signaling system allows communication between bacteria and their mammalian hosts. AI-3 is produced by many bacterial species (80), and Epi and NE are host stress hormones (36, 56). This system was first described as a system activating virulence traits in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) (55, 75). The signals are sensed by histidine sensor kinases (HKs), two of which have been identified: QseC, which senses AI-3, Epi, and NE (24), and QseE, which senses Epi, sulfate, and phosphate (67).

QseC is found in several bacteria, including Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, which causes human gastroenteritis. However, this organism causes also systemic infection in murine models (8, 28). QseC's homolog in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium shares 87% sequence identity with EHEC's QseC (66), and a Salmonella serovar Typhimurium qseC mutant can be complemented with the EHEC qseC gene, demonstrating that the HKs of these two organisms are functionally interchangeable (59). QseC of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium is important for efficient colonization of swine (9). There have been contradictory reports concerning the role of Epi/NE in QseC-mediated motility in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (9, 60), and the variations can be accounted for by the labile nature of the Epi/NE signals in vitro (4; http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/sigma-aldrich/home.html). Transcriptome studies of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium also revealed a role for Epi and QseC in the antimicrobial peptide and oxidative stress resistance responses (50). QseC's response to its signals can be inhibited by the α-adrenergic antagonist phentolamine (24) and the small molecule LED209. LED209 inhibits QseC in three different pathogens, EHEC, Salmonella serovar Typhimurium, and Francisella tularensis, and prevents pathogenesis in vitro and in vivo (66).

The second bacterial adrenergic HK, QseE, senses Epi, sulfate, and phosphate to activate expression of virulence genes in EHEC. Together with QseG and QseF, QseE has been implicated in pedestal formation directly related to EHEC pathogenesis (67, 68). A QseE homolog is also present in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium and shares 87% sequence identity with EHEC's QseE. However, the role of QseE in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium pathogenesis remains unknown.

Salmonella serovar Typhimurium pathogenesis is a complex process. The role of flagellar motility in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium pathogenesis is controversial. This motility was reported previously to not play a role in Salmonella virulence in vivo (53). However, flagella induce inflammation via Toll-like receptor 5 during Salmonella infection of the intestinal mucosa (32, 35, 77). During its evolution, Salmonella serovar Typhimurium acquired many pathogenicity islands (57). The main pathogenicity islands involved in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium infection are Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) and SPI-2, which encode type III secretion systems (T3SSs) essential for Salmonella serovar Typhimurium virulence (38-40, 62, 71). The SPI-1-encoded T3SS is required for efficient invasion of the intestinal epithelium (39), while the SPI-2-encoded T3SS is essential for Salmonella serovar Typhimurium replication and survival within macrophages and systemic infection in mice (23, 43, 62). In Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, the flagellar sigma factor FliA regulates SPI-1 expression and affects bacterial invasion of epithelial cells. However, this phenotype has not been observed in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (29).

The SPI-1 locus encodes effectors and regulators, such as HilA, HilD, HilC, and InvF. SPI-1 contains three operons, the prg-org, inv-spa, and sic-sip operons. The prg-org and inv-spa operons encode the needle complex, and the sic-sip operon encodes the translocon that embeds itself in the host cell membrane. Additional effectors are encoded in other SPIs in the Salmonella serovar Typhimurium chromosome (30). HilD mediates transcriptional cross talk between SPI-1 and SPI-2, providing sequential activation of the loci. This mechanism allows Salmonella serovar Typhimurium to invade using the SPI-1-encoded T3SS and survive within the cellular vacuole using the SPI-2-encoded T3SS (17). InvF, encoded by the first gene of the inv-spa operon, is an AraC-type transcriptional activator required for SPI-1 expression.

The SPI-1 effectors SopE, SopE2, and SopB in a pathogen, as well as the Rho GTPases Cdc42, Rac1, and RhoG in a host, are required for orchestrated and efficient invasion. Together, these molecules lead to actin cytoskeletal reorganization, membrane ruffling, and bacterial internalization by macropinocytosis. The presence of SopB, together with the effectors mentioned above, leads to chloride secretion through lipid dephosphorylation (85), and SopB indirectly stimulates Cdc42 and RhoG through its phosphoinositide phosphatase activity (16, 42, 64, 85). SopB also promotes intestinal disease by increasing the intracellular concentration of d-myo-inositol 1,4,5,6-tetrakisphosphate, which stimulates cellular chloride secretion and fluid flux (85). Although SipA is not required for cell invasion, it helps initiate actin polymerization at the site of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium entry by decreasing the critical concentration and increasing the stability of actin filaments (44, 58, 86).

The effector SifA (encoded outside SPI-2) is secreted through the SPI-2 T3SS and is essential for inducing tubulation of the Salmonella serovar Typhimurium phagosome. SifA binds to the mammalian kinesin-binding protein SKIP. SifA coexpressed with SseJ induces tubulation of mammalian cell endosomes, indicating that SifA likely mimics or activates a RhoA family of GTPases (63).

SPI-3 (containing the mgtBC genes), together with SPI-2, is required for intramacrophage survival, virulence in mice, and growth in magnesium-depleted medium. The mgtC gene is transcriptionally controlled by the PhoP-PhoQ regulatory system (15), which is responsive to Mg2+, antimicrobial peptides, and pH and is the major regulator of virulence in Salmonella (6, 22).

The BasRS two-component system, also known as PmrAB, is an important regulator of the Salmonella serovar Typhimurium virulence genes. PmrAB regulates genes that modify lipopolysaccharide, conferring resistance to cationic microbial peptides, such as polymyxin B, and subsequently aiding survival within the host (41). Expression of pmrAB is also indirectly regulated by the PhoPQ system, and QseC has been linked to regulation of pmrAB (59, 60).

Here we show that QseC plays an important role in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium pathogenicity in vitro and in vivo. A qseC mutant shows diminished flagellar motility, invasion of epithelial HeLa cells, survival within J774 macrophages, and virulence in a systemic murine infection. Additionally, Dbh−/− mice (which are unable to produce Epi and NE) infected with the Salmonella serovar Typhimurium wild type (WT) and the qseC mutant have different infection kinetics than WT mice. These findings suggest that the AI-3/Epi/NE signaling system plays an important role in interkingdom signaling during Salmonella serovar Typhimurium infection in vivo. QseC globally regulates transcription expression of SPI-1, the SPI-2 effector sifA, SPI-3, and flagellar genes in vitro and in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains were grown aerobically in LB or N-minimal medium (17, 23, 27, 54) at 37°C. Recombinant DNA and molecular biology techniques were performed as previously described (69). All oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description or relevant genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| SL1344 | Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium prototype | 46 |

| CGM220 | qseC mutant λ Red generate | 66 |

| CGM222 | qseC complemented strain (in XhoI/HindIII pBADMycHisA) | This study |

| TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80lacZΔM15) hsdR17 | Stratagene |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBADMycHisA | Cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pBlueScript KSII | Cloning vector | Stratagene |

| TOPO PCR Blunt | PCR blunt cloning vector with topoisomerase | Invitrogen |

| pKD3 | pANTSγ derivative containing FRT-flanked chloramphenicol resistance | 26 |

| pKD46 | l red recombinase expression plasmid | 26 |

| pKD20 | TS replication and thermal induction of FLP synthesis | 19 |

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

|---|---|---|

| sipA | TTTAGTAGCCGCCTGCGATAA | GCCGTGGTACCGTCTACCA |

| sopB | CGGGTACCGCGTCAATTTC | TGGCGGCGAACCCTATAAA |

| invF | CAGGACTCAGCAAAACCCATTT | TTATCGATGGCGCAGGATTAG |

| sifA | GTTGTCTAATGGAACCGATAATATCG | CTACCCCCTCCCTTCGACAT |

| mgtB | ACTTCATTGCGCCCATACACT | CGTCAGGGCCTCACGATAGA |

| fliA | TTGGTGCGTAATCGTTTGATG | CTGGAAGTCGGCGAATCG |

| flhDC | GTCAAACCGGAAATGACAAACTAA | ACCCTGCCGCAGATGGT |

| motA | TTACCGCCGCGACGATA | CCAACAGTCTGGCGATGGT |

| basS | CGGTAAAAAGGCGTTCATTGTC | CGTCTCGGCGATCAATCAA |

| qseB | CCACTGGCCCTAAAACCAAAA | GGCAGCACGCGACCTTT |

| rpoA | GCGCTCATCTTCTTCCGAAT | CGCGGTCGTGGTTATGTG |

| qseC-Lambda Red | TGACGCAACGTCTCAGCCTGCGCGTCAGGCTGACGCTTATTTTCCTGATTGTGTAGGCTGGGAGCTGCTTC | CCAACTTACTACGGCCTCAAATCCACCTTCCGCGGCGTTGCCAAACGACACATATGAATATCCTCCTTA |

| qseC-pBADMycHisA | CTCGAGATAAATTGACGCAACGTCTCAGC | AAGCTTCGCCAACTTACTACGGCCTCAAA |

Construction of the qseC mutant.

An isogenic nonpolar Salmonella serovar Typhimurium SL1344 qseC mutant was constructed using λ red mutagenesis (26). This qseC mutant (CGM220) was complemented with the qseC gene cloned (XhoI and HindIII) in the pBADMycHisA (Invitrogen) vector, generating strain CGM222.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Overnight cultures were grown aerobically in LB or N-minimal medium at 250 rpm to late exponential growth phase (optical density at 600 nm, 1.0) for the in vitro assays in the absence or presence of 50 μM NE. The in vivo expression levels were measured by directly extracting the Salmonella serovar Typhimurium RNA from the spleens and livers of infected animals. Negative control PCRs were performed with RNA extracted from livers and spleens of uninfected animals to ensure that there was no cross-reactivity of our primers with mammalian mRNA. RNA was extracted from three biological samples using a RiboPure bacterial RNA isolation kit (Ambion) by following the manufacturer's guidelines. The primers used in the real-time assays were designed using Primer Express v1.5 (Applied Biosystems) (Table 2). Real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed in one step using an ABI 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). For each 20-μl reaction mixture, 10 μl 2× SYBR master mixture, 0.1 μl Multiscribe reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems), and 0.1 μl RNase inhibitor (Applied Biosystems) were added. The amplification efficiency of each primer pair was verified using standard curves prepared with known RNA concentrations. The rpoA (RNA polymerase subunit A) gene was used as the endogenous control. Data collection was performed using the ABI Sequence Detection 1.3 software (Applied Biosystems). Data were normalized to levels of rpoA and analyzed using the comparative critical threshold (CT) method described previously (81). The levels of expression of the target genes at the different growth phases were compared using the relative quantification method (81). Real-time data are expressed below as fold changes compared to WT levels. Error bars in the figures indicate the standard deviations of the ΔΔCT values (81). Statistical significance was determined by using Student's t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. All raw qRT-PCR data can be found in the supplemental tables.

HeLa cell invasion assays.

Epithelial HeLa cells were infected with Salmonella serovar Typhimurium at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100:1 for 90 min to examine bacterium-cell interactions at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2, as previously described (33, 34, 65). The cells were treated with 40 μg/ml of gentamicin for 1 h to kill extracellular bacteria and lysed with 1% Triton X-100. Bacteria were diluted and plated on LB medium plates to determine the number of CFU (33, 34, 65).

Macrophage infection.

J774 murine macrophages were infected with opsonized Salmonella serovar Typhimurium with normal mouse serum at 37°C for 15 min and washed. The macrophages were infected using an MOI of 100:1 for 30 min to examine bacterium-cell interactions at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. The cells were treated with 40 μg/ml of gentamicin for 1 h to kill extracellular bacteria and lysed with 1% Triton X-100. Bacteria were diluted and plated on LB medium plates to determine the number of CFU (28, 33, 65).

Motility assays.

The motility assays were performed at 37°C using LB broth containing 0.3% agar (76). The transcriptional expression of the flagellum genes, flhDC, fliA, and motA, was measured by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) using RNA extracted directly from halos cut out of the LB motility agar.

Survival of mice with Salmonella serovar Typhimurium.

Mice (129x1/SvJ 7, 9 weeks old, female) were infected intraperitoneally (IP) with 1 × 108 CFU of E. coli K-12 strain DH5α (K-12 was used as a negative infectivity control to ensure that there were no issues with organ perforation during IP injection and that the death of mice was not due to endotoxic effects), Salmonella serovar Typhimurium WT strain SL1344, or the qseC mutant (CGM220). Ten mice were infected IP with each strain using the same IP method and 1 × 108 CFU, and the experiments were repeated at least twice to ensure reproducibility. Mice were returned to their cages and monitored daily for signs of morbidity (anorexia, rapid shallow breathing, scruffy fur, decreased muscle tone, and lethargy) and death. At 7 days postinfection the remaining animals were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation. Systemic colonization of organs was performed as previously described (28), and after 20 h of IP infection the mice were sacrificed to remove the spleens and livers. These organs were harvested and homogenized, and the homogenates were plated on LB agar plates for bacterial cell counting to determine tissue colonization (CFU) (28, 62).

Mixed IP infection with the Salmonella serovar Typhimurium WT and the qseC mutant was performed using one-half of the WT strain inoculum usually used and one-half of the qseC inoculum usually used (1 × 104 CFU of each strain or a total of 2 × 104 CFU). The eight mice used were sacrificed at 20 h postinfection, and organs were collected and plated to determine the bacterial loads. The ratio of ΔqseC mutant counts to WT counts was used to determine the competitive index (12, 28, 70).

Dbh knockout mice.

Dopamine β-hydroxylase knockout (Dbh−/−) mice, maintained with a mixed C57BL/6J and 129 SvEv background, were generated at Emory University as previously described (2), shipped to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, and infected IP with the WT and the qseC mutant as described above. Littermate Dbh+/− heterozygous mice were used as controls because they had normal NE and Epi levels (78).

RESULTS

QseC affects flagellar motility.

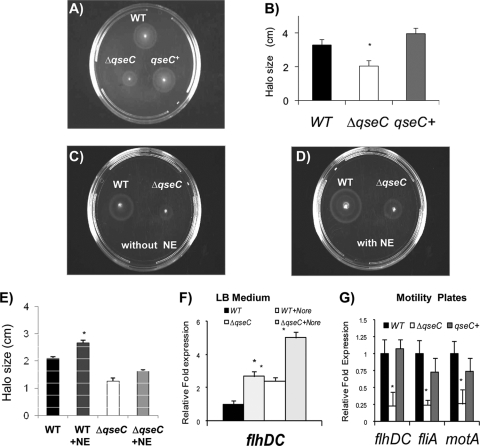

The QseC system directly activates flagellar expression in EHEC by regulating transcription of the flhDC genes that encode the flagellar master regulators (25, 76). Moreover, Bearson and Bearson (9) have shown that NE enhances motility and flagellar gene expression via QseC in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (9). Contradictory data concerning NE/Epi enhancement of motility were reported by Merighi et al. (60), suggesting that Epi did not play a role in enhancement of motility in WT Salmonella serovar Typhimurium. However, it is worth noting that in vitro NE and Epi are photosensitive and labile compounds that quickly decompose in solution (4). The labile nature of these compounds could be responsible for the variation described in the previous motility studies. Since both Bearson and Bearson and Merighi et al. (9, 60) reported decreased motility of qseC mutants, we first investigated the motility phenotype of our qseC mutant, and congruent with both previous reports, we observed decreased motility compared to the WT and the phenotype was rescued by complementation (Fig. 1A and 1B). Although NE has been shown to increase expression of flagellum genes in WT Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (9), there have been no reports of QseC regulation of the flagellum regulon in this species. In agreement with the report of Bearson and Bearson (9), we observed that NE significantly increased motility of the WT strain (Fig. 1C, 1D, and 1E) but that in the presence of NE the motility of the qseC mutant was still decreased (Fig. 1C, 1D, and 1E). Surprisingly, in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium cultures grown in LB medium, transcription of flhDC was 2-fold greater in the qseC mutant than in the WT (Fig. 1F). We hypothesized that QseC-dependent flagellar gene expression may be differentially regulated in LB medium and in motility agar. To test this hypothesis, we assessed expression of the flagellar genes flhDC, fliA, and motA in the WT, qseC mutant, and complemented strains by performing qRT-PCR with RNA extracted from cultures grown in motility agar. Under these conditions, we observed diminished transcription of all of the flagellar genes in the qseC mutant (transcription of flhDC was significantly decreased 4-fold, transcription of fliA was significantly decreased 4-fold, and transcription of motA was significantly decreased 3-fold), and this phenotype was rescued by complementation (Fig. 1G), explaining the decreased motility observed for the qseC mutant (Fig. 1A and B).

FIG. 1.

QseC regulation of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium's flagella in vitro. (A) Motility assay performed in plates containing LB medium with 0.3% agar after 8 h. (B) Sizes of motility halos after 8 h. (C) Motility assay performed with the WT and ΔqseC strains using LB medium without NE after 8 h. (D) Motility assay performed with the WT and ΔqseC strains in LB medium with 50 μM NE after 8 h. (E) Sizes of motility halos after norepinephrine (NE) addition at 8 h. (F) Transcription of flhDC in the WT strain and the ΔqseC mutant in LB medium with and without 50 μM norepinephrine (Nore). (G) Transcription of flagellar genes (flhDC, fliA, and motA) in WT, ΔqseC, and complemented strains in motility agar. Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test based on comparison with the expression in the WT strain (*, P < 0.001). qseC+, complemented strain.

Consistent with previous reports (9, 24), NE increased expression of flhDC during growth in the WT and in the qseC mutant (in both strains expression was increased 2-fold) in LB medium (Fig. 1F). There are two potential explanations for the differential regulation of flhDC by QseC under different environmental conditions (LB medium versus motility plates). (i) Transcriptional regulation of flhDC is complex and can vary within a species due to the presence of insertion sequences in the regulatory region of flhDC (7). To add to this complexity, QseB binds to different sites according to its phosphorylated state and can act as a repressor and activator within the same promoter (47). The flhDC regulatory region in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium lacks one of the QseB binding sites present in the EHEC flhDC regulatory region (21), which may account for the differential and environment-dependent regulation of these genes in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium compared to EHEC. (ii) Salmonella serovar Typhimurium NE-dependent flhDC expression in LB broth may also occur through a second receptor. Salmonella serovar Typhimurium harbors a QseE homolog, and QseE senses Epi/NE (67). Cross-signaling between the QseBC and QseEF systems has also been observed (47). Different receptors may play a role in NE modulation of flhDC expression under different environmental conditions, since transcription of flhDC in LB medium is increased in the qseC mutant (Fig. 1F), while it is decreased in motility agar (Fig. 1G).

Furthermore it is also worth noting that FlhDC is the master flagellar regulator and that transcriptional regulation of flhDC is sensitive to several environmental conditions and cell state sensors (20). The promoter of flhDC defines the flagellar class 1 promoter and is a crucial point at which the decision to initiate or prevent flagellar biosynthesis occurs. This promoter is controlled by a number of global regulators, such as cyclic AMP receptor protein (74, 83), heat shock proteins DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE (72), and H-NS (11, 82), as well as by several environmental signals, such as temperature, high concentrations of inorganic salts, carbohydrates, or alcohols, growth phase, DNA supercoiling, phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylglycerol synthesis, and cell cycle control (21).

QseC plays a role in invasion of epithelial cells and intramacrophage survival.

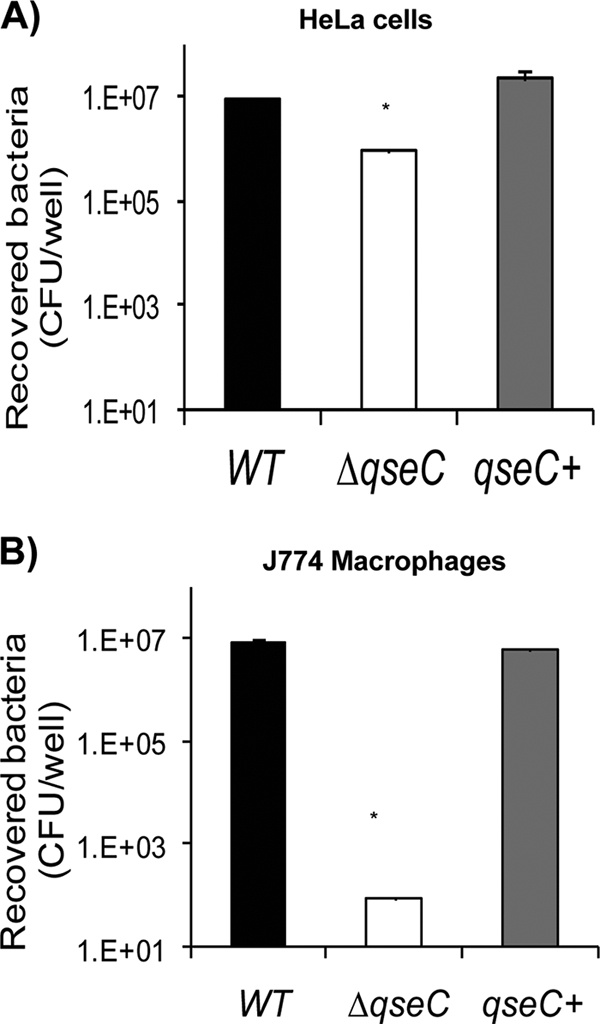

Next we investigated whether QseC affected Salmonella serovar Typhimurium invasion of HeLa cells and survival within J774 macrophages. There was a significant 1-order-of-magnitude decrease in HeLa cell invasion by the qseC mutant compared to the WT (Fig. 2A), and there was a 5-order-of-magnitude decrease in survival of the qseC mutant compared to the WT in J774 macrophages (Fig. 2B). Both phenotypes were rescued by complementation (Fig. 2A and B). These data suggest that expression of both SPI-1- and SPI-2-encoded T3SSs and/or effectors is regulated by QseC.

FIG. 2.

Involvement of QseC in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium invasion of HeLa cells and intramacrophage survival. (A) Invasion of HeLa epithelial cells by WT, ΔqseC, and complemented strains. (B) Intramacrophage survival (J774 macrophages) of WT, ΔqseC, and complemented strains. Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test based on comparison with the WT strain (*, P < 0.001). qseC+, complemented strain.

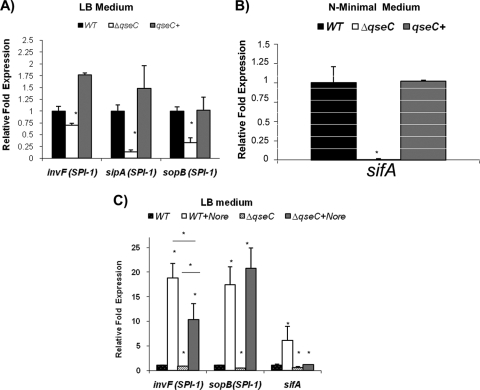

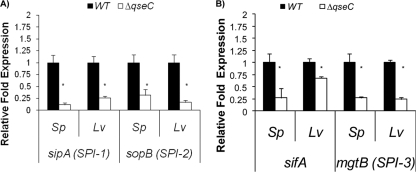

HeLa cell invasion is an SPI-1-dependent phenotype, while SPI-2 is involved in intramacrophage survival (37-39). Expression of the SPI-1 genes invF, sipA, and sopB was assessed by qRT-PCR under conditions conducive to SPI-1 expression (LB medium) (17). Transcription of these genes was significantly decreased in the qseC mutant; expression of invF was decreased 2-fold, expression of sipA was decreased 5-fold, and expression of sopB was decreased 2.5-fold. Expression of all of these genes was rescued by complementation (Fig. 3A). Transcription of the gene encoding the SPI-2 T3SS effector SifA under conditions optimal for SPI-2 expression (N-minimal medium, which is a low-phosphate and low-magnesium medium [17]) was strikingly reduced in the qseC mutant (it was 100-fold lower than transcription in the WT) and was also rescued by complementation (Fig. 3B). These results are congruent with the decreased ability of the qseC mutant to invade epithelial cells and survive within macrophages (Fig. 2).

FIG. 3.

QseC regulates transcriptional expression of SPI-1 and sifA in vitro. (A) Transcription of SPI-1 genes in WT, ΔqseC, and complemented strains in LB medium. (B) Transcription of sifA in WT, ΔqseC, and complemented strains in N-minimal medium. (C) Transcription of invF (SPI-1), sopB (SPI-1), and sifA in WT and ΔqseC strains in LB medium in the absence and presence of 50 μM NE. In all cases expression levels were compared to WT expression levels without NE. In addition, a second analysis of the expression of invF was performed by comparing the expression in the WT strain with NE and the expression in the ΔqseC mutant with NE, as indicated. Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test (*, P < 0.001). Nore, norepinephrine; qseC+, complemented strain.

Because QseC is one of the sensors for Epi/NE (24), we investigated whether NE could activate expression of the genes mentioned above in a QseC-dependent manner. NE increased expression of invF (18-fold), sopB (17-fold), and sifA (6-fold) in WT Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (Fig. 3C). However, only NE-induced sifA expression was completely dependent on QseC (Fig. 3C). NE-induced expression of invF was significantly decreased but not eliminated in the qseC mutant, and there was a significant 2-fold decrease in the qseC mutant with NE compared to the WT with NE (Fig. 3C). Meanwhile, NE-induced expression of sopB was similar in the WT and the qseC mutant (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that in vitro induction of sifA transcription by NE is completely QseC dependent, which is congruent with our previous studies (66). However, NE-induced transcription of invF is only partially dependent on QseC (there was a significant 2-fold decrease in the qseC mutant with NE compared to the WT with NE), while transcription of sopB in vitro can be induced by NE even in the absence of QseC, suggesting that another NE receptor, maybe QseE, could play a role in this regulation.

QseC in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium systemic infection of mice.

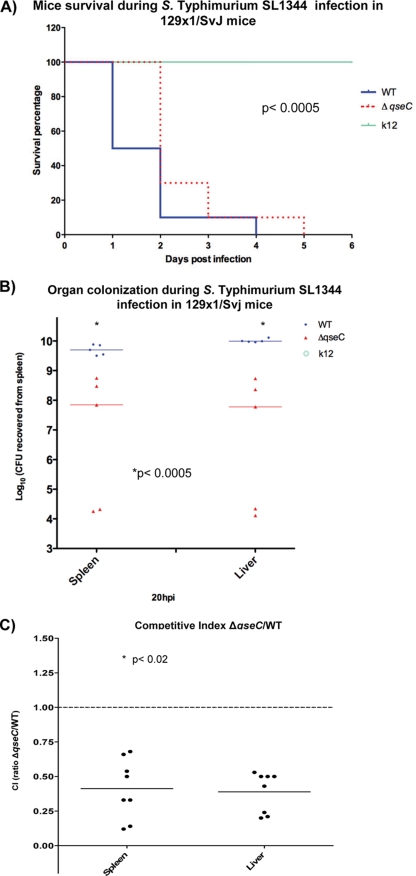

Inasmuch as QseC regulates expression of the SPI-1 and sifA genes (Fig. 3) and plays an important role in epithelial cell invasion and intramacrophage survival (Fig. 2), one would expect that a qseC mutant would be attenuated for murine infection. Indeed, we found previously that a qseC mutant was attenuated for systemic infection of mice by performing survival studies (66). Here we conducted further murine infection experiments to assess in more detail this attenuation for infectivity. We used the systemic (intraperitoneal [IP] infection) typhoid-like model with 129x1/SvJ mice, which are Nramp1+/+ (79) and more resistant to Salmonella serovar Typhimurium infection (18). This murine strain was chosen because we obtained knockout mice that do not produce either epinephrine or norepinephrine in this background (see Fig. 7 and 8) and we needed consistency in the genetic background of the animals to compare and contrast data. As a negative control we also performed IP infection using E. coli K-12 (Fig. 4A and B; see Fig. 7) to ensure that endotoxic effects were not responsible for the morbidity and mortality observed in the animals. After infection with WT Salmonella serovar Typhimurium, 50% of the mice were still alive at day 1 postinfection, while 100% of the qseC mutant-infected mice were still alive at this time (Fig. 4A). By day 2 only 10% of the WT strain-infected mice were still alive, while 30% of the qseC mutant-infected mice were still alive. All WT strain-infected mice were dead by day 4 postinfection, while all qseC mutant-infected mice were dead by day 5 (Fig. 4A). Colonization of the spleens and livers of mice (at 20 h postinfection) was significantly less (2 orders of magnitude less) for the qseC mutant than for the WT (Fig. 4B). We also determined a competitive index for the WT and the qseC mutant in mice. Competition studies were performed to avoid issues concerning individual variation between different mice when the abilities of the strains to become established in the spleens and livers of the animals were scored. As an initial control, an in vitro competition experiment with the WT and the qseC mutant was performed to ensure that the qseC mutant did not have growth defects (data not shown). Figure 4C shows that the WT strain outcompeted the qseC mutant, further indicating that the qseC mutant was attenuated for systemic murine infection.

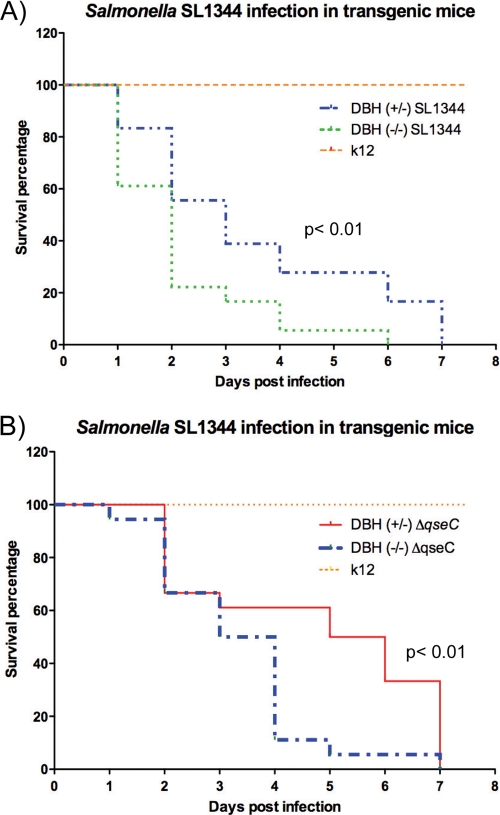

FIG. 7.

Salmonella serovar Typhimurium infection in Dbh−/− knockout mice. (A) Survival plots for Dbh+/− and Dbh−/− mice infected IP with WT Salmonella serovar Typhimurium strain SL1344. (B) Survival plots for Dbh+/− and Dbh−/− mice infected IP with the ΔqseC mutant. Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test.

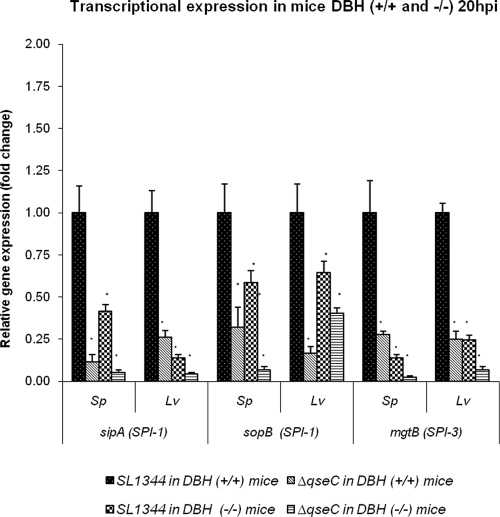

FIG. 8.

Differential transcriptional expression of SPI-1 and SPI-3 in Dbh−/− mutant mice. Transcription of sipA, sopB, and mgtB in spleens and livers harvested from WT and Dbh−/− mice 20 h after IP infection with the WT and the ΔqseC mutant. Statistical significance was based on a comparison of expression levels to expression levels in WT Salmonella serovar Typhimurium in Dbh+/+ mice and was determined by Student's t test (*, P < 0.001). Sp, spleens; Lv, livers; hpi, hours postinfection.

FIG. 4.

QseC's role in murine systemic infection. (A) Survival curves for 129x1/SvJ mice infected intraperitoneally (IP) with WT Salmonella serovar Typhimurium, the ΔqseC isogenic mutant, and E. coli K-12 as control (P < 0.0005, as determined using Student's t test and comparing the qseC mutant to the WT at every time point on the survival curve until 5 days postinfection). (B) Organ loads of WT Salmonella serovar Typhimurium and the ΔqseC isogenic mutant during systemic dissemination in 129x1/SvJ mice at 20 h postinfection (hpi) (P < 0.0005). (C) Competitive index (CI) for the qseC mutant and WT strain SL1344 in 129x1/SvJ mice 20 h postinfection (ratio of ΔqseC systemic dissemination to WT systemic dissemination). Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test (P < 0.02).

QseC-dependent gene regulation in vivo.

The attenuation of the qseC mutant during systemic infection could have been a result of the QseC regulation of SPI-1 genes and sifA (Fig. 3). However, in vitro conditions do not exactly reflect the complexity of the in vivo environment. Hence, we investigated the role of QseC in the regulation of these virulence genes during infection. We harvested the spleens and livers of 129x1/SvJ mice infected with either the WT or the qseC mutant (three mice each) 20 h postinfection, extracted the RNA, and performed qRT-PCR using rpoA as an internal control. Transcription of the SPI-1 genes sipA (4-fold) and sopB (3-fold) in both spleens and livers and transcription of the sifA gene (4-fold in spleens and 1.4-fold in livers) were significantly decreased in the qseC mutant from infected animals (Fig. 5). We also examined transcription of the SPI-3 mgtB gene, which is known to be important for intramacrophage survival (14, 15). Transcription of the mgtB gene was also decreased (4-fold) in the qseC mutant in both spleens and livers (Fig. 5B). These data suggest that QseC activates expression of the SPI-1, sifA, and SPI-3 genes in vitro (Fig. 3) and in vivo (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

QseC regulates transcriptional expression in vivo of SPI-1, sifA, and SPI-3. (A) Transcription of sipA and sopB in spleens and livers harvested from 129x1/SvJ mice 20 h after IP infection with the WT or the ΔqseC mutant. (B) Transcription of sifA and mgtB in spleens and livers harvested from 129x1/SvJ mice 20 h after IP infection with the WT or the ΔqseC mutant. Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test (*, P < 0.001). Sp, spleens; Lv, livers.

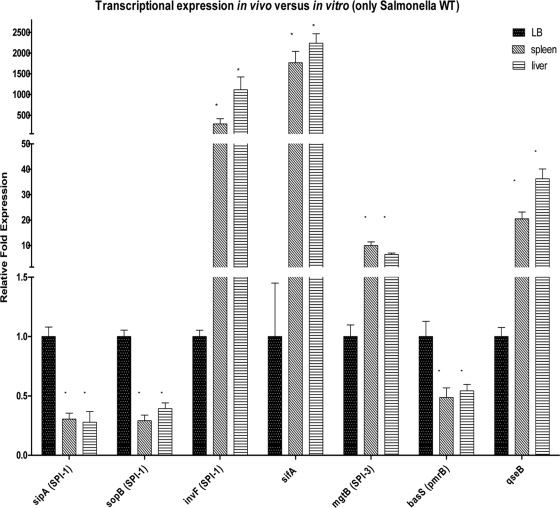

We also compared expression of these genes in the Salmonella serovar Typhimurium WT strain in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 6) and observed that the transcription of the SPI-1 genes sipA and sopB was significantly decreased in vivo compared to the transcription in vitro. Given that our in vivo assessment was performed with livers and spleens and that SPI-1's major role seems to be a role in the invasion of the intestinal epithelia, these results were not unexpected. One exception is the expression of invF, which is an SPI-1 gene and is highly upregulated in vivo. InvF is a transcriptional factor, and given the cross regulation of SPI-1 and SPI-2 by the SPI-1-encoded HilD regulator (17), it is possible that in vivo invF is needed to control other genes in Salmonella involved in systemic disease. Expression of sifA, mgtB, and qseB was significantly upregulated in vivo, reflecting of the role of these genes in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium systemic infection.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of transcriptional expression in WT strain SL1344 in vitro (LB broth) and in vivo (spleens and livers). All statistical and expression analyses were performed by comparing expression levels to LB broth expression levels. Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test (*, P < 0.001).

Role of NE/Epi in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium infection in vivo.

Since QseC is important for systemic infection of mice by Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (Fig. 4) and since QseC senses AI-3, Epi, and NE (24), we assessed the role of QseC-sensing Epi and NE during infection of mice by Salmonella by using Dbh−/− mice that lack NE and Epi (3). It is worth noting that although NE and Epi are not required for normal development of the immune system of these mice, they play an important role in the modulation of T-cell-mediated immunity to infection. Specifically, these mice have impaired Th1 T-cell responses to infection (3). Th1 T cells are important in controlling intracellular pathogens (51, 61, 73). Consequently, Dbh−/− mice are more susceptible to intracellular pathogens (Listeria monocytogenes and Mycobacterium tuberculosis) (3).

To assess whether the Dbh−/− knockout mice were more susceptible to Salmonella serovar Typhimurium infection, we infected Dbh−/− and Dbh+/− control mice with the WT strain. Congruent with previous reports, the Dbh−/− mice were more susceptible to Salmonella serovar Typhimurium infection than the Dbh+/− mice (Fig. 7A). By day 2 postinfection 80% of the Dbh−/− mice were dead, while only 45% of the Dbh+/− were dead. All of the Dbh−/− mice were dead by day 6, while all of the Dbh+/− mice were dead by day 7 (Fig. 7A). We next infected Dbh−/− and Dbh+/− mice with the qseC mutant and observed that during the first 3 days, the levels of mortality due to the qseC mutant were similar for the two mouse strains (Fig. 7B). These results highlight an important difference compared with infection by WT Salmonella serovar Typhimurium, in which the defect in the Th1 immune response to infection by intracellular pathogens in the Dbh−/− mice impairs control of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium of infection (Fig. 7A). On day 3 20% of the WT-infected Dbh−/− mice were still alive, while 40% of the WT-infected Dbh+/− mice were still alive (Fig. 7A). Meanwhile, 70% of both the Dbh−/− and Dbh+/− mice infected with the qseC mutant were still alive on day 2 postinfection, and on day 3 60% of the Dbh+/− mice and 50% of the Dbh−/− mice were still alive (Fig. 7B). However, from day 4 to day 7, Dbh−/− mice were more susceptible to infection by the qseC mutant than Dbh+/− mice, and the scenario was similar to that observed with mice infected with WT Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (Fig. 7A and 7B). These data are congruent with data for infection of 129x1/SvJ mice (Nramp1+/+) (Fig. 4), where attenuation due to a qseC mutation was observed only until day 3 postinfection, suggesting that QseC-independent regulation is involved in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium pathogenesis at later time points. These results suggest that QseC, Epi, and NE play a significant role in the infection of mice by Salmonella serovar Typhimurium.

In vivo QseC-Epi/NE-dependent gene regulation.

Although Dbh−/− mice are more susceptible to intracellular pathogens due to an immune deficiency, these mice could yield valuable information concerning QseC-dependent Epi/NE signaling during Salmonella serovar Typhimurium infection. To assess QseC-Epi/NE-dependent regulation in vivo, we performed qRT-PCR using RNA extracted from the livers and spleens of control and Dbh−/− mice infected with WT and ΔqseC mutant Salmonella serovar Typhimurium. Expression of the SPI-1 genes sipA and sopB and the SPI-3 gene mgtB in the livers and spleens was significantly diminished in the absence of Epi/NE or QseC and was even further reduced in Dbh−/− mice infected with ΔqseC Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (Fig. 8). These results suggest that NE/Epi facilitates expression of these genes in vivo and that QseC is involved in this regulation (Fig. 8). The data also show that during murine infection Epi/NE modulates virulence gene expression in Salmonella and that this modulation is QseC dependent.

DISCUSSION

The complex interaction between a bacterial pathogen and its mammalian host relies on signaling through proteins, bacterial effectors, or toxins delivered to host cells, as well as chemicals (48). Here we show the intersection of the two signaling systems in vitro and in vivo in the important pathogen Salmonella serovar Typhimurium. Salmonella serovar Typhimurium is a food-borne pathogen that after ingestion invades the gastrointestinal epithelia, reaching the mesenteric lymph nodes. It then can establish a systemic infection, replicating in the spleen and liver of the host (35, 39, 45, 49, 84). During pathogenesis, bacteria encounter several different microenvironments in the host (10), and several bacteria, including Salmonella serovar Typhimurium, effectively adapt by utilizing HKs (5). QseC is an HK that senses the bacterial signal AI-3 and the host hormones Epi/NE (24). The concentrations of NE are much higher in lymphoid organs than in the blood, suggesting that NE plays a physiological role in immune modulation (1, 31). NE/Epi is known to have profound systemic effects and plays important roles in energy balance, behavior, cardiovascular tone, thermoregulation, and the stress response (52). Hence, a pathogen's ability to sense these two signals may allow precise modulation of virulence gene expression, while the physiological state of the host is gauged.

Here we show that QseC is a global regulator of virulence genes of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 1 to 8). A qseC mutant exhibits decreased expression of the SPI-1, sifA, and SPI-3 genes and a decreased ability to invade epithelial cells and replicate within macrophages, and it is attenuated for systemic infection of mice (Fig. 1 to 8). In contrast to our results, Merighi et al. (60) reported that a qseC mutant did not exhibit attenuation for the invasion of epithelial cells. These conflicting data could be due to differences in methodology; Merighi et al. preincubated Salmonella serovar Typhimurium with epithelial cells at 4°C for 30 min and then at 37°C for 1 h before they added gentamicin (60), while we incubated bacteria at 37°C for 90 min before gentamicin was added, as previously described (33, 34, 65), without performing the 4°C preincubation step used in the studies of Merighi et al. However, the cell invasion defect that we observed is congruent with the downregulation of SPI-1 gene expression that we observed in the qseC mutant (Fig. 3).

The qseC mutant was attenuated for systemic infection of mice (Fig. 4) (66), congruent with the reduced expression of the sifA gene in the qseC mutant (Fig. 3B) (66) and the 5-order-of-magnitude decrease in the intramacrophage survival of the qseC mutant (Fig. 2B). The SifA effector is secreted by the SPI-2 TTSS and has been shown to be important for systemic infection of mice and intramacrophage survival (13). Our results also show that expression of sifA and mgtB (an SPI-3 gene also important for intramacrophage survival [14, 15]) is downregulated in the qseC mutant compared to the WT in the spleens and livers of infected mice (Fig. 5).

To further address the interaction between Epi/NE and Salmonella serovar Typhimurium pathogenesis, we utilized Dbh−/− mice that do not produce the Epi/NE signals. These mice were more susceptible to Salmonella serovar Typhimurium infection than control mice (Fig. 7A). Although this may seem to be a conundrum given that Epi/NE enhances Salmonella serovar Typhimurium pathogenesis in vitro and a qseC sensor mutant is attenuated for murine infection (Fig. 4), one has to take into consideration the finding that Epi/NE is important for Th1 T-cell activation, which mediates the defense against intracellular pathogens (3). Hence, the greater susceptibility of the Dbh−/− mice to Salmonella serovar Typhimurium infection is likely due to a defective Th1 immune response. However, it is still possible to utilize these animals to gain important insights into the role of Epi/NE during systemic Salmonella serovar Typhimurium infection. It is noteworthy that there was not any difference in the infectivity of the qseC mutant in Dbh−/− and Dbh+/− mice until 3 days postinfection (Fig. 7B), suggesting that early in infection QseC sensing of Epi/NE may play an important role in the kinetics of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium infection of mice. These data are further corroborated by the observations that transcription of Salmonella's SPI-1 and SPI-3 genes in vivo is decreased in the absence of Epi/NE and that QseC is involved in this regulation (Fig. 8).

The transcription of the sipA, sopB, and mgtB genes in WT Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (which contains QseC and produces AI-3) in the spleens and livers of Dbh−/− mice (which do not produce Epi/NE) is significantly decreased compared to the expression of these genes in WT Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (which contains QseC and produces AI-3) in the spleens and livers of WT mice (which produce Epi/NE) (Fig. 8). These data suggest that during murine infection, the presence of Epi/NE in the livers and spleens of mice activates expression of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium virulence genes.

QseC senses AI-3, Epi, and NE (24). To address QseC's involvement in sensing Epi/NE in vivo, we infected WT mice (which produce Epi/NE) and Dbh−/− mice (which do not produce Epi/NE) with the qseC mutant and compared the expression of the sipA, sopB, and mgtB genes to the expression of these genes in WT Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (which contains QseC and makes AI-3) infecting WT mice. During infection of WT mice, the host signal Epi/NE is present, as is the bacterial AI-3 signal produced by the qseC mutant. We observed that under these conditions transcription of all three of these genes was decreased in the qseC mutant compared to the transcription in WT Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (Fig. 8), suggesting that the ability to sense the three signals is involved in the transcriptional activation of these virulence genes during murine infection. Transcription of sipA (in livers and spleens), sopB (in spleens), and mgtB (in livers and spleens) is decreased even further in the qseC mutant infecting Dbh−/− mice, suggesting that both QseC and Epi/NE are necessary for full activation of these genes in vivo. Although we show that QseC is an important sensor of these cues, it is clear that other bacterial adrenergic sensors exist. NE-induced transcription of the SPI-1 genes (Fig. 3C) is not completely dependent on QseC. We have identified a second adrenergic receptor in EHEC, QseE (67), and Salmonella serovar Typhimurium contains a homolog of this protein. The QseC-independent NE gene regulation could occur through this second sensor and would impart further kinetics and refinement to this signaling cascade. Further support for a role for a secondary adrenergic sensor in this regulation can be obtained if transcription of sipA and mgtB in the qseC mutant in the livers and spleens of WT mice is compared with transcription of these genes in the livers and spleens of Dbh−/− mice (Fig. 8). Transcription of these genes in the qseC mutant is further decreased during infection of Dbh−/− mice, suggesting that a second adrenergic receptor (maybe QseE) may be responsible for the residual QseC-independent Epi/NE activation of these genes in WT mice. In this study we assessed the contribution of interkingdom chemical signaling to Salmonella serovar Typhimurium pathogenesis by combining the powerful genetics of murine models and a genetically tractable pathogen. Further understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying these signaling events in the bacteria and the host should allow us to examine interkingdom signaling in more depth.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant UO1-AI053067 and by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 December 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ader, R., N. Cohen, and D. Felten. 1995. Psychoneuroimmunology: interactions between the nervous system and the immune system. Lancet 345:99-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmer, B. M., M. G. Thomas, R. A. Larsen, and K. Postle. 1995. Characterization of the exbBD operon of Escherichia coli and the role of ExbB and ExbD in TonB function and stability. J. Bacteriol. 177:4742-4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alaniz, R. C., S. A. Thomas, M. Perez-Melgosa, K. Mueller, A. G. Farr, R. D. Palmiter, and C. B. Wilson. 1999. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase deficiency impairs cellular immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:2274-2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnett, C. D., J. Wright, and N. Zenker. 1978. Synthesis and adrenergic activity of benzimidazole bioisosteres of norepinephrine and isoproterenol. J. Med. Chem. 21:72-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashby, M. K. 2004. Survey of the number of two-component response regulator genes in the complete and annotated genome sequences of prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 231:277-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bader, M. W., S. Sanowar, M. E. Daley, A. R. Schneider, U. Cho, W. Xu, R. E. Klevit, H. Le Moual, and S. I. Miller. 2005. Recognition of antimicrobial peptides by a bacterial sensor kinase. Cell 122:461-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker, C. S., B. M. Pruss, and P. Matsumura. 2004. Increased motility of Escherichia coli by insertion sequence element integration into the regulatory region of the flhD operon. J. Bacteriol. 186:7529-7537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumler, A. J., R. M. Tsolis, P. J. Valentine, T. A. Ficht, and F. Heffron. 1997. Synergistic effect of mutations in invA and lpfC on the ability of Salmonella typhimurium to cause murine typhoid. Infect. Immun. 65:2254-2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bearson, B. L., and S. M. Bearson. 2008. The role of the QseC quorum-sensing sensor kinase in colonization and norepinephrine-enhanced motility of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microb. Pathog. 44:271-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beier, D., and R. Gross. 2006. Regulation of bacterial virulence by two-component systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:143-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertin, P., E. Terao, E. H. Lee, P. Lejeune, C. Colson, A. Danchin, and E. Collatz. 1994. The H-NS protein is involved in the biogenesis of flagella in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 176:5537-5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beuzon, C. R., and D. W. Holden. 2001. Use of mixed infections with Salmonella strains to study virulence genes and their interactions in vivo. Microbes Infect. 3:1345-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beuzon, C. R., S. Meresse, K. E. Unsworth, J. Ruiz-Albert, S. Garvis, S. R. Waterman, T. A. Ryder, E. Boucrot, and D. W. Holden. 2000. Salmonella maintains the integrity of its intracellular vacuole through the action of SifA. EMBO J. 19:3235-3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanc-Potard, A. B., and E. A. Groisman. 1997. The Salmonella selC locus contains a pathogenicity island mediating intramacrophage survival. EMBO J. 16:5376-5385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanc-Potard, A. B., F. Solomon, J. Kayser, and E. A. Groisman. 1999. The SPI-3 pathogenicity island of Salmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 181:998-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchwald, G., A. Friebel, J. E. Galan, W. D. Hardt, A. Wittinghofer, and K. Scheffzek. 2002. Structural basis for the reversible activation of a Rho protein by the bacterial toxin SopE. EMBO J. 21:3286-3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bustamante, V. H., L. C. Martinez, F. J. Santana, L. A. Knodler, O. Steele-Mortimer, and J. L. Puente. 2008. HilD-mediated transcriptional cross-talk between SPI-1 and SPI-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:14591-14596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canonne-Hergaux, F., S. Gruenheid, G. Govoni, and P. Gros. 1999. The Nramp1 protein and its role in resistance to infection and macrophage function. Proc. Assoc. Am. Physicians 111:283-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cherepanov, P. P., and W. Wackernagel. 1995. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158:9-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chilcott, G. S., and K. T. Hughes. 2000. Coupling of flagellar gene expression to flagellar assembly in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:694-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chilcott, G. S., and K. T. Hughes. 1998. The type III secretion determinants of the flagellar anti-transcription factor, FlgM, extend from the amino-terminus into the anti-sigma28 domain. Mol. Microbiol. 30:1029-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho, U. S., M. W. Bader, M. F. Amaya, M. E. Daley, R. E. Klevit, S. I. Miller, and W. Xu. 2006. Metal bridges between the PhoQ sensor domain and the membrane regulate transmembrane signaling. J. Mol. Biol. 356:1193-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cirillo, D. M., R. H. Valdivia, D. M. Monack, and S. Falkow. 1998. Macrophage-dependent induction of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system and its role in intracellular survival. Mol. Microbiol. 30:175-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke, M. B., D. T. Hughes, C. Zhu, E. C. Boedeker, and V. Sperandio. 2006. The QseC sensor kinase: a bacterial adrenergic receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:10420-10425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clarke, M. B., and V. Sperandio. 2005. Transcriptional regulation of flhDC by QseBC and sigma (FliA) in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1734-1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deiwick, J., T. Nikolaus, S. Erdogan, and M. Hensel. 1999. Environmental regulation of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1759-1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Detweiler, C. S., D. M. Monack, I. E. Brodsky, H. Mathew, and S. Falkow. 2003. virK, somA and rcsC are important for systemic Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection and cationic peptide resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 48:385-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eichelberg, K., and J. E. Galan. 2000. The flagellar sigma factor FliA (σ28) regulates the expression of Salmonella genes associated with the centisome 63 type III secretion system. Infect. Immun. 68:2735-2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellermeier, J. R., and J. M. Slauch. 2007. Adaptation to the host environment: regulation of the SPI1 type III secretion system in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:24-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felten, D. L., S. Y. Felten, D. L. Bellinger, S. L. Carlson, K. D. Ackerman, K. S. Madden, J. A. Olschowki, and S. Livnat. 1987. Noradrenergic sympathetic neural interactions with the immune system: structure and function. Immunol. Rev. 100:225-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feuillet, V., S. Medjane, I. Mondor, O. Demaria, P. P. Pagni, J. E. Galan, R. A. Flavell, and L. Alexopoulou. 2006. Involvement of Toll-like receptor 5 in the recognition of flagellated bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:12487-12492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fierer, J., L. Eckmann, F. Fang, C. Pfeifer, B. B. Finlay, and D. Guiney. 1993. Expression of the Salmonella virulence plasmid gene spvB in cultured macrophages and nonphagocytic cells. Infect. Immun. 61:5231-5236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finlay, B. B., S. Ruschkowski, and S. Dedhar. 1991. Cytoskeletal rearrangements accompanying salmonella entry into epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 99:283-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freed, N. E., O. K. Silander, B. Stecher, A. Bohm, W. D. Hardt, and M. Ackermann. 2008. A simple screen to identify promoters conferring high levels of phenotypic noise. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furness, J. B. 2000. Types of neurons in the enteric nervous system. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 81:87-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galan, J. E. 1996. Molecular and cellular bases of Salmonella entry into host cells. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 209:43-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galan, J. E. 1996. Molecular genetic bases of Salmonella entry into host cells. Mol. Microbiol. 20:263-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galan, J. E., and R. Curtiss III. 1989. Cloning and molecular characterization of genes whose products allow Salmonella typhimurium to penetrate tissue culture cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:6383-6387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Groisman, E. A., and H. Ochman. 1993. Cognate gene clusters govern invasion of host epithelial cells by Salmonella typhimurium and Shigella flexneri. EMBO J. 12:3779-3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gunn, J. S., S. S. Ryan, J. C. Van Velkinburgh, R. K. Ernst, and S. I. Miller. 2000. Genetic and functional analysis of a PmrA-PmrB-regulated locus necessary for lipopolysaccharide modification, antimicrobial peptide resistance, and oral virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 68:6139-6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hardt, W. D., L. M. Chen, K. E. Schuebel, X. R. Bustelo, and J. E. Galan. 1998. S. typhimurium encodes an activator of Rho GTPases that induces membrane ruffling and nuclear responses in host cells. Cell 93:815-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hensel, M., J. E. Shea, S. R. Waterman, R. Mundy, T. Nikolaus, G. Banks, A. Vazquez-Torres, C. Gleeson, F. C. Fang, and D. W. Holden. 1998. Genes encoding putative effector proteins of the type III secretion system of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 are required for bacterial virulence and proliferation in macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 30:163-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Higashide, W., S. Dai, V. P. Hombs, and D. Zhou. 2002. Involvement of SipA in modulating actin dynamics during Salmonella invasion into cultured epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 4:357-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hobbie, S., L. M. Chen, R. J. Davis, and J. E. Galan. 1997. Involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in the nuclear responses and cytokine production induced by Salmonella typhimurium in cultured intestinal epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 159:5550-5559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoiseth, S. K., and B. A. Stocker. 1981. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature 291:238-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hughes, D. T., M. B. Clarke, K. Yamamoto, D. A. Rasko, and V. Sperandio. 2009. The QseC adrenergic signaling cascade in enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hughes, D. T., and V. Sperandio. 2008. Inter-kingdom signaling: communication between bacteria and host. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:111-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Humphries, A. D., M. Raffatellu, S. Winter, E. H. Weening, R. A. Kingsley, R. Droleskey, S. Zhang, J. Figueiredo, S. Khare, J. Nunes, L. G. Adams, R. M. Tsolis, and A. J. Baumler. 2003. The use of flow cytometry to detect expression of subunits encoded by 11 Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium fimbrial operons. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1357-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karavolos, M. H., H. Spencer, D. M. Bulmer, A. Thompson, K. Winzer, P. Williams, J. C. Hinton, and C. M. Khan. 2008. Adrenaline modulates the global transcriptional profile of Salmonella revealing a role in the antimicrobial peptide and oxidative stress resistance responses. BMC Genomics 9:458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lapaque, N., T. Walzer, S. Meresse, E. Vivier, and J. Trowsdale. 2009. Interactions between human NK cells and macrophages in response to Salmonella infection. J. Immunol. 182:4339-4348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levi-Montalcini, R., and P. U. Angeletti. 1966. Second symposium on catecholamines. Modification of sympathetic function. Immunosympathectomy. Pharmacol. Rev. 18:619-628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lockman, H. A., and R. Curtiss III. 1990. Salmonella typhimurium mutants lacking flagella or motility remain virulent in BALB/c mice. Infect. Immun. 58:137-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lundberg, U., U. Vinatzer, D. Berdnik, A. von Gabain, and M. Baccarini. 1999. Growth phase-regulated induction of Salmonella-induced macrophage apoptosis correlates with transient expression of SPI-1 genes. J. Bacteriol. 181:3433-3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lyte, M., B. P. Arulanandam, and C. D. Frank. 1996. Production of Shiga-like toxins by Escherichia coli O157:H7 can be influenced by the neuroendocrine hormone norepinephrine. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 128:392-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lyte, M., and S. Ernst. 1992. Catecholamine induced growth of gram negative bacteria. Life Sci. 50:203-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marcus, S. L., J. H. Brumell, C. G. Pfeifer, and B. B. Finlay. 2000. Salmonella pathogenicity islands: big virulence in small packages. Microbes Infect. 2:145-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McGhie, E. J., R. D. Hayward, and V. Koronakis. 2001. Cooperation between actin-binding proteins of invasive Salmonella: SipA potentiates SipC nucleation and bundling of actin. EMBO J. 20:2131-2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Merighi, M., A. Carroll-Portillo, A. N. Septer, A. Bhatiya, and J. S. Gunn. 2006. Role of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium two-component system PreA/PreB in modulating PmrA-regulated gene transcription. J. Bacteriol. 188:141-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Merighi, M., A. N. Septer, A. Carroll-Portillo, A. Bhatiya, S. Porwollik, M. McClelland, and J. S. Gunn. 2009. Genome-wide analysis of the PreA/PreB (QseB/QseC) regulon of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. BMC Microbiol. 9:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meurens, F., M. Berri, G. Auray, S. Melo, B. Levast, I. Virlogeux-Payant, C. Chevaleyre, V. Gerdts, and H. Salmon. 2009. Early immune response following Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhimurium infection in porcine jejunal gut loops. Vet. Res. 40:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ochman, H., F. C. Soncini, F. Solomon, and E. A. Groisman. 1996. Identification of a pathogenicity island required for Salmonella survival in host cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:7800-7804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ohlson, M. B., Z. Huang, N. M. Alto, M. P. Blanc, J. E. Dixon, J. Chai, and S. I. Miller. 2008. Structure and function of Salmonella SifA indicate that its interactions with SKIP, SseJ, and RhoA family GTPases induce endosomal tubulation. Cell Host Microbe 4:434-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patel, J. C., and J. E. Galan. 2006. Differential activation and function of Rho GTPases during Salmonella-host cell interactions. J. Cell Biol. 175:453-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pfeifer, C. G., S. L. Marcus, O. Steele-Mortimer, L. A. Knodler, and B. B. Finlay. 1999. Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes are induced upon bacterial invasion into phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells. Infect. Immun. 67:5690-5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rasko, D. A., C. G. Moreira, R. Li de, N. C. Reading, J. M. Ritchie, M. K. Waldor, N. Williams, R. Taussig, S. Wei, M. Roth, D. T. Hughes, J. F. Huntley, M. W. Fina, J. R. Falck, and V. Sperandio. 2008. Targeting QseC signaling and virulence for antibiotic development. Science 321:1078-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reading, N. C., D. A. Rasko, A. G. Torres, and V. Sperandio. 2009. The two-component system QseEF and the membrane protein QseG link adrenergic and stress sensing to bacterial pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:5889-5894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reading, N. C., A. G. Torres, M. M. Kendall, D. T. Hughes, K. Yamamoto, and V. Sperandio. 2007. A novel two-component signaling system that activates transcription of an enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli effector involved in remodeling of host actin. J. Bacteriol. 189:2468-2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 70.Shea, J. E., C. R. Beuzon, C. Gleeson, R. Mundy, and D. W. Holden. 1999. Influence of the Salmonella typhimurium pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system on bacterial growth in the mouse. Infect. Immun. 67:213-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shea, J. E., M. Hensel, C. Gleeson, and D. W. Holden. 1996. Identification of a virulence locus encoding a second type III secretion system in Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:2593-2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shi, W., Y. Zhou, J. Wild, J. Adler, and C. A. Gross. 1992. DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE are required for flagellum synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 174:6256-6263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Siegemund, S., N. Schutze, S. Schulz, K. Wolk, K. Nasilowska, R. K. Straubinger, R. Sabat, and G. Alber. 2009. Differential IL-23 requirement for IL-22 and IL-17A production during innate immunity against Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis. Int. Immunol. 21:555-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Silverman, M., and M. Simon. 1974. Characterization of Escherichia coli flagellar mutants that are insensitive to catabolite repression. J. Bacteriol. 120:1196-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sperandio, V., A. G. Torres, B. Jarvis, J. P. Nataro, and J. B. Kaper. 2003. Bacteria-host communication: the language of hormones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:8951-8956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sperandio, V., A. G. Torres, and J. B. Kaper. 2002. Quorum sensing Escherichia coli regulators B and C (QseBC): a novel two-component regulatory system involved in the regulation of flagella and motility by quorum sensing in E. coli. Mol. Microbiol. 43:809-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stecher, B., M. Barthel, M. C. Schlumberger, L. Haberli, W. Rabsch, M. Kremer, and W. D. Hardt. 2008. Motility allows S. Typhimurium to benefit from the mucosal defence. Cell. Microbiol. 10:1166-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thomas, S. A., and R. D. Palmiter. 1998. Examining adrenergic roles in development, physiology, and behavior through targeted disruption of the mouse dopamine beta-hydroxylase gene. Adv. Pharmacol. 42:57-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Threadgill, D. W., D. Yee, A. Matin, J. H. Nadeau, and T. Magnuson. 1997. Genealogy of the 129 inbred strains: 129/SvJ is a contaminated inbred strain. Mamm. Genome 8:390-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Walters, M., M. P. Sircili, and V. Sperandio. 2006. AI-3 synthesis is not dependent on luxS in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 188:5668-5681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Walters, M., and V. Sperandio. 2006. Autoinducer 3 and epinephrine signaling in the kinetics of locus of enterocyte effacement gene expression in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 74:5445-5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yanagihara, S., S. Iyoda, K. Ohnishi, T. Iino, and K. Kutsukake. 1999. Structure and transcriptional control of the flagellar master operon of Salmonella typhimurium. Genes Genet. Syst. 74:105-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yokota, T., and J. S. Gots. 1970. Requirement of adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic phosphate for flagella formation in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 103:513-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang, S., R. L. Santos, R. M. Tsolis, S. Stender, W. D. Hardt, A. J. Baumler, and L. G. Adams. 2002. The Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium effector proteins SipA, SopA, SopB, SopD, and SopE2 act in concert to induce diarrhea in calves. Infect. Immun. 70:3843-3855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhou, D., L. M. Chen, L. Hernandez, S. B. Shears, and J. E. Galan. 2001. A Salmonella inositol polyphosphatase acts in conjunction with other bacterial effectors to promote host cell actin cytoskeleton rearrangements and bacterial internalization. Mol. Microbiol. 39:248-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhou, D., M. S. Mooseker, and J. E. Galan. 1999. Role of the S. typhimurium actin-binding protein SipA in bacterial internalization. Science 283:2092-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.