Abstract

Background: Brain metastases reduce survival because therapeutic options are limited. This phase II study evaluated the efficacy of single-agent therapy with alternating weekly, dose-dense temozolomide in pretreated patients with brain metastases prospectively stratified by primary tumor type.

Methods: Eligible patients had bidimensionally measurable brain metastases from histologically/cytologically confirmed melanoma, breast cancer (BC), or non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Prior chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT) were allowed. Patients received temozolomide 150 mg/m2/day (days 1–7 and 15–21 every 28- or 35-day cycle).

Results: In the intent-to-treat population (N = 157; 53 melanoma, 51 BC, and 53 NSCLC), one patient had complete response, nine (6%) had partial responses, and 31 (20%) had stable disease in the brain. Median progression-free survival was 56, 58, and 66 days for melanoma, BC, and NSCLC, respectively. Median overall survival was 100 days for melanoma, 172 days for NSCLC, and not evaluable in the BC group. Thrombocytopenia was the most common adverse event causing dose modification or treatment discontinuation. Grade 4 toxic effects were rare.

Conclusions: This alternating weekly, dose-dense temozolomide regimen was well tolerated and clinically active in heavily pretreated patients with brain metastases, particularly in patients with melanoma. Combining temozolomide with WBRT or other agents may improve clinical outcomes.

Keywords: brain metastases, breast cancer, dose dense, melanoma, NSCLC, temozolomide

introduction

It is estimated that 8%–10% of patients with advanced cancer will develop symptomatic brain metastases at some point during the course of their disease [1–3]. Brain metastases are particularly frequent in cancers of the lung (40%–50%), breast (15%–25%), and in melanoma (5%–20%) and increasingly are being diagnosed because of advancements in imaging techniques and better control of primary systemic disease resulting in improved survival [3]. Brain metastases are associated with a poor prognosis; without treatment, median survival is 1–2 months [4]. Standard of care for brain metastases is whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT), stereotactic radiosurgery, or surgery [3]. Median survival achieved with WBRT is 3–4 months [3]. A pioneering study (N = 1200) evaluating prognostic factors associated with survival in patients with brain metastases treated with radiation therapy concluded that survival ranged from 7.1 months in patients with Karnofsky performance status (KPS) ≥70, <65 years old, controlled systemic disease, and brain as the only site of metastases [Recursive Partitioning Analysis (RPA) class I], compared with 4.2 months in patients categorized as RPA class II, to 2.3 months in patients with KPS <70 with uncontrolled systemic disease (RPA class III) [5, 6]. Numerous trials have explored systemic chemotherapy, including temozolomide, taxane/platinum regimens, vinorelbine/gemcitabine, and topotecan either alone or in combination with WBRT [7–9]. Median overall survival (OS) in these studies ranged from 4.5 to 6.6 months, and most of these patients had brain metastases from lung cancer. Clinical benefit data in patients with brain metastases originating from other malignancies are limited.

Temozolomide is a second-generation, oral alkylating agent with excellent central nervous system (CNS) bioavailability and proven activity against primary brain tumors [10–13]. In addition, temozolomide is well tolerated, and hematologic toxicity is usually noncumulative. O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) is a key DNA repair enzyme responsible for tumor resistance to alkylating agents [14, 15]. Based on studies by Tolcher et al. [16] showing that dose-dense regimens of temozolomide (including the alternating weekly regimen) deplete MGMT levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, it has been hypothesized that dose-dense temozolomide may deplete MGMT in tumor cells and increase antitumor activity. Accordingly, several clinical trials have evaluated dose-dense temozolomide regimens in patients with primary brain tumors [17, 18].

Previous studies of systemic chemotherapy for brain metastases have largely enrolled patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) along with small numbers of patients with breast cancer (BC) and melanoma [7, 8, 19–23]. No systematic studies have examined the benefit of temozolomide in patients prospectively stratified by primary malignancy. The present study examined clinical benefit and safety of an alternating weekly (7/14-day), dose-dense temozolomide regimen in patients with brain metastases from melanoma or from breast or lung cancer that were not amenable to surgery or radiosurgery. Patients were prospectively stratified by their primary tumor type.

methods

patients

inclusion criteria.

Patients with a cytologic/histologic diagnosis of NSCLC (first or second line), malignant melanoma (first or second line), or BC and one or more measurable brain metastases ≥1 cm in diameter were eligible. Eligible patients must have completed previous anticancer therapy at least 4 weeks before study entry. All enrolled patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of zero to two and acceptable hematologic (leukocytes ≥ 3.5 × 109 cells/l; platelets ≥ 100 × 109 cells/l), liver (bilirubin ≤ 25 μM), and renal (creatinine ≤ 150 μM; creatinine clearance ≥ 60 ml/min) function. After the third and only substantial amendment, inclusion criteria were extended to include irradiated brain metastases. The final and approved protocol and informed consent were reviewed and approved by the local ethics committee. The study was conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

exclusion criteria.

Before the third amendment, patients were excluded if they had received prior WBRT for brain metastases; however, after the third amendment, WBRT for brain metastases was allowed if completed ≥2 months before study entry. Patients with brain metastases amenable to neurosurgery/radiosurgery were excluded; however, residual or progressive malignant disease after neurosurgery was allowed. Patients with diabetes precluding administration of adequate doses of dexamethasone and patients requiring chronic anticonvulsant therapy were also excluded.

study design

This was a multicenter, open-label, two-step, phase II trial, and patients were prospectively stratified by primary tumor type. The primary end point was clinical benefit, defined as best radiologic response [including complete response (CR), partial response (PR), or stable disease (SD)] achieved during the study period. Secondary end points included progression-free survival (PFS), neurological progression-free survival (NPFS), OS, and safety.

assessments.

Baseline measurements of the brain included either magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with or without gadolinium enhancement, or computed tomography (CT). In cases where a brain lesion diagnosis was not equivocal, a radiolabeled leukocyte brain scan (HexaMethylPropylene Amine Oxime 99Tc brain single-photon emission computed tomography) was carried out to rule out infectious disease and improve diagnostic accuracy. At baseline, after the first 2 months of treatment, and every 3 months thereafter, clinical and radiologic (CT or MRI) evaluation of brain and other sites of disease was carried out until disease progression. Other baseline measurements included physical examination, hematology, and biochemistry. During study treatment, a CT or an MRI of the brain was carried out every two cycles until disease progression. After the third amendment, a radiologic confirmation of response after 4 weeks was introduced in case of response or SD. Tumor response was evaluated on the basis of World Health Organization response criteria [24]. The best response during study treatment was reported. Response duration was monitored, and responses maintained for at least 4 weeks as evaluated by a sequential CT scan or MRI were recorded. Adverse events (AEs) were graded according to the National Cancer Institute—Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) v3.0.

treatment.

Patients received temozolomide orally, in a fasting state, at a starting dose of 150 mg/m2 once daily for seven consecutive days repeated every other week [days 1–7 and 15–21 of every 28-day cycle (schedule A)]. The treatment schedule was altered for all patients enrolled after the third amendment to include seven additional days of rest from days 22 to 35, increasing the cycle length to 35 days (schedule B). Treatment was continued until either unacceptable toxicity or disease progression. Dexamethasone was administered daily at a dose of 2–16 mg i.m. or i.v. for the first 2 months; thereafter, an optimal dose of dexamethasone necessary to maintain stable neurological symptoms was administered. In the event of an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) <1500 cells/μl or a platelet count <100 000/μl at any time while on therapy, treatment was delayed until recovery to ANC ≥1500 cells/μl and platelet count ≥100 000/μl. The dose was reduced to 125 mg/m2/day if ANC was <500 cells/μl for 5 days, if ANC was <500 cells/μl with fever and/or platelet count <25 000/μl, or if therapy was delayed by ≥2 weeks. In the event of NCI-CTCAE grade 3 or 4 non-hematologic toxicity, including gastrointestinal toxicity unresponsive to standard therapy, dosing was delayed until toxicity resolved to baseline or grade 1. Dose reduction to the next lower dose level was also recommended.

statistical analysis.

Following the Simon optimal two-stage design for phase II studies, the trial was designed to refuse a clinical benefit rate ≤10% (minimal benefit rate required to continue study after completion of first step) and to provide 90% statistical power for assessing therapeutic activity of a clinical benefit rate of 25% with an alpha error <0.05. Double data entry was used to eliminate input error. All data were analyzed using SAS 9.1. The statistical analysis was carried out by Quintiles, Milan, Italy. Continuous variables were summarized by descriptive statistics, and categoric variables were summarized using counts of subjects and percentages, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). PFS and OS were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method. Only patients who received at least one dose of study treatment were included in the analysis [modified intent-to-treat population (mITT)].

results

patients

During the first step of the trial, 63 patients were enrolled (21 for each tumor type). The clinical benefit (PR plus SD) was 24% (40% for melanoma, 19% for BC, and 24% for NSCLC); therefore, the trial continued to the second step. In total, 162 patients (54 melanoma, 53 BC, and 55 NSCLC) were enrolled across 25 study centers in Italy from December 2000 to October 2005. Eighty-three patients (37 melanoma, 22 breast, and 24 NSCLC) were enrolled from December 2000 to October 2002 and were treated on a 28-day cycle (schedule A). After the third amendment, 79 patients (17 melanoma, 31 breast, and 31 NSCLC) were enrolled and treated on a 35-day cycle (schedule B). Of these, 157 patients received at least one dose of study drug and were included in the mITT analysis. Five patients (one with melanoma, two with BC, and two with NSCLC) were never treated and were not included in the analysis. Baseline characteristics of the mITT population are shown in Table 1. In the mITT population, 98 (62%) patients had received prior chemotherapy for systemic disease and 41 (26%) patients had received prior radiotherapy for the treatment of brain metastases. Overall, 47 (30%) of the patients had received one prior chemotherapy regimen, 19 (12%) had received two prior regimens, and 32 (20%) had received three or more prior regimens. Patients with BC were more heavily pretreated compared with the other cohorts.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics (modified intent-to-treat population)

| Characteristic | Melanoma (n = 53) | Breast cancer (n = 51) | NSCLC (n = 53) |

| Age, years, mean ± standard deviation | 51.1 ± 11.0 | 53.9 ± 11.7 | 59.1 ± 7.6 |

| Sex | |||

| Male, n (%) | 34 (64) | 1 (2) | 37 (70) |

| Body surface area, mean ± standard deviation | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 29 (55) | 17 (33) | 23 (43) |

| 1 | 18 (34) | 24 (47) | 25 (47) |

| 2 | 6 (11) | 10 (20) | 5 (10) |

| Prior therapy for systemic disease, n (%) | |||

| Chemotherapy | 21 (40) | 41 (80) | 36 (68) |

| Radiotherapy | 2 (2) | 20 (39) | 12 (23) |

| Whole-brain radiotherapy, n (%) | 14 (26) | 12 (24) | 15 (28) |

| No. of prior chemotherapy regimens, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 32 (60) | 10 (20) | 17 (32) |

| 1 | 13 (24) | 13 (25) | 21 (40) |

| 2 | 4 (8) | 6 (12) | 9 (17) |

| ≥3 | 4 (8) | 22 (43) | 6 (11) |

NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer.

The total number of delivered cycles (both schedules) was 356. The primary reason for study withdrawal was disease progression, accounting for 66% of patients on both schedules (Table 2). Overall, 18% of the patients discontinued study treatment because of AEs.

Table 2.

Reason for study withdrawal

| No. of patients (%) | |||

| Melanoma (n = 53) | Breast cancer (n = 51) | NSCLC (n = 53) | |

| Relapse or progressive disease | 38 (72) | 33 (65) | 33 (62) |

| Serious adverse events | 9 (17) | 8 (16) | 12 (23) |

| Investigator's decision | 2 (4) | 3 (6) | 4 (8) |

| Withdrawal of consent | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | 1 (2) |

| Other reason | 3 (6) | 4 (8) | 3 (6) |

NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer.

efficacy assessments

The overall objective response rate was 6% (one CR and nine PR), and 31 (20%) patients in the mITT population had SD (Table 3). The disease control rate was 32% (95% CI 20% to 46%) for melanoma (9% PR, 23% SD), 20% (95% CI 10% to 33%) for BC (4% PR, 16% SD), and 26% (95% CI 15% to 40%) for NSCLC (2% CR, 4% PR, 21% SD). However, the majority of responses and SD were transient; only 13 (32%) of the objective responses or SD were confirmed at a 4-week follow-up scan. Response rate and disease control rate were similar regardless of treatment schedule in patients with BC or NSCLC. In patients with melanoma, the response rate was marginally higher in patients treated on schedule A. Disease control rate was also higher in patients who did not receive prior WBRT. Among melanoma patients, the disease control rate was 34% in patients who did not receive prior WBRT compared with 22% in patients who did receive prior WBRT; among BC patients, disease control was achieved only in patients who did not receive prior WBRT (23% versus 0%); and in NSCLC patients, the disease control rate was 29% in patients who did not receive prior WBRT compared with 18% in those who did. Because of the high number of missing data, a formal analysis of neurological symptoms could not be carried out.

Table 3.

Brain tumor response by tumor type and treatment schedule

| Schedule A, n (%) [CI] | Schedule B, n (%) [CI] | Overall, n (%) [CI] | Total, n (%) | |||||||

| Melanoma (n = 36) | BC (n = 22) | NSCLC (n = 23) | Melanoma (n = 17) | BC (n = 29) | NSCLC (n = 30) | Melanoma (n = 53) | BC (n = 51) | NSCLC (n = 53) | N = 157 | |

| CR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (<1) |

| PR | 4 (11) | 1 (5) | 1 (4) | 1 (6) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 5 (9) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 9 (6) |

| SD | 9 (25) | 5 (23) | 5 (22) | 3 (18) | 3 (10) | 6 (20) | 12 (23) | 8 (16) | 11 (21) | 31 (20) |

| Disease control (CR + PR + SD) | 13 (36) [21–54] | 6 (27) [11–50] | 6 (26) [10–48] | 4 (24) [7–50] | 4 (14) [4–32] | 8 (27) [12–46] | 17 (32) [20–46] | 10 (20) [10–33] | 14 (26) [15–40] | 41 (26) |

| PD | 23 (64) [46–79] | 16 (73) [50–89] | 17 (74) [52–90] | 13 (77) [50–93] | 25 (86) [68–96] | 22 (73) [54–88] | 36 (68) [54–80] | 41 (80) [67–90] | 39 (74) [60–85] | 116 (74) |

CI, confidence interval; BC, breast cancer; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

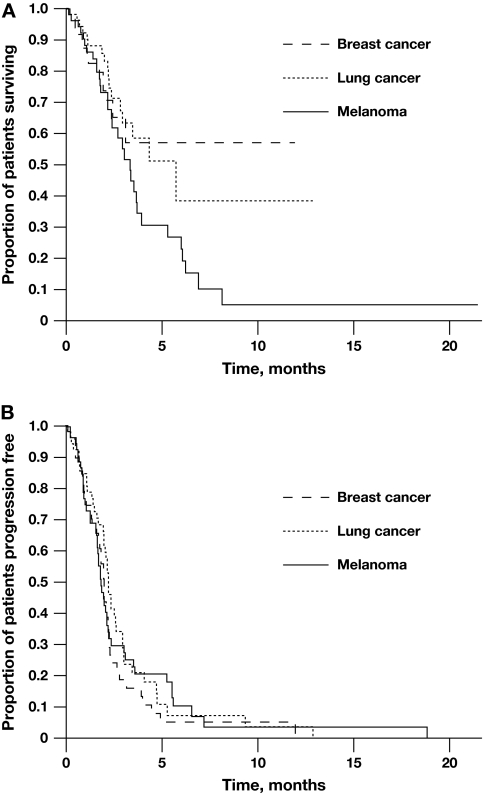

Median PFS ranged from 1.9 months in the melanoma group to 2.2 months in the NSCLC group (Figure 1A). Median NPFS was similar and ranged from 2.1 to 2.5 months across all groups and showed no significant difference with modification of the treatment schedule. Median OS ranged from 3.3 months in the melanoma group to 5.7 months in the NSCLC group (Figure 1B). Median OS was not reached in the BC group.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of progression-free (A) and overall survival (B) by tumor type.

safety

The most commonly reported AEs were lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, nausea, vomiting, headache, and asthenia (Table 4). The frequency of all AEs was lower with schedule B. Thrombocytopenia resulted in dose reduction or treatment discontinuation in 30 (19%) patients and occurred at a lower frequency in patients treated on schedule B. Lymphopenia was the most common grade 3 toxicity. Grade 4 hepatic toxicity and grade 4 leukopenia were rare and occurred in ≤2% of patients.

Table 4.

Common adverse events (all grades)

| Schedule A, n (%) | Schedule B, n (%) | All histologies, n (%) (N = 157) | |||||

| Melanoma (n = 36) | BC (n = 22) | NSCLC (n = 23) | Melanoma (n = 17) | BC (n = 29) | NSCLC (n = 30) | ||

| Lymphopenia | 15 (42) | 7 (32) | 10 (44) | 1 (6) | 6 (21) | 6 (20) | 45 (29) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 12 (33) | 6 (27) | 15 (65) | 1 (6) | 6 (21) | 6 (20) | 46 (29) |

| Nausea | 12 (33) | 5 (23) | 5 (22) | 1 (6) | 3 (10) | 2 (7) | 28 (18) |

| Vomiting | 12 (33) | 6 (27) | 3 (13) | 2 (12) | 4 (14) | 4 (13) | 31 (20) |

| Headache | 7 (19) | 6 (27) | 3 (13) | 3 (18) | 3 (10) | 4 (13) | 26 (17) |

| Asthenia | 7 (19) | 6 (27) | 7 (30) | 2 (12) | 1 (3) | 7 (23) | 30 (19) |

BC, breast cancer; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer.

discussion

This study represents the first large, multicenter study of a dose-dense temozolomide regimen in patients with brain metastases, in which patients were prospectively stratified by primary tumor type. Although this study, designed in 2000, has certain limitations because data were not collected on control of systemic disease at baseline, and patients were not stratified by RPA class, the results are no less important. The rationale for the treatment regimen was based on several considerations. First, temozolomide effectively crosses the blood–brain barrier and has demonstrated good clinical activity against primary brain tumors [11–13]. Second, dose-dense temozolomide regimens may overcome resistance to alkylating agents.

The results of the present study demonstrated that this regimen has activity in patients with brain metastases from all three tumor types, particularly melanoma. In addition, antitumor activity appeared to be greater in patients who had not received prior irradiation for brain metastases and in patients who were less heavily pretreated with chemotherapy for systemic disease. Patients with BC had the lowest disease control rate but were also more heavily pretreated than patients with melanoma or NSCLC. The main limitation of this regimen was that patients progressed quickly, and both PFS and OS were relatively short. In addition, the regimen caused dose-limiting thrombocytopenia in a subset of patients, which is consistent with data reported in other studies with this regimen [18, 25]. This is not surprising given that the majority of patients had received prior chemotherapy for systemic disease. This prompted lengthening of the cycle to allow a longer recovery period; the amended treatment cycle reduced the frequency of all AEs without compromising the survival benefit.

The limited activity and transient nature of the tumor responses observed across tumor types in this study has been documented in other trials of systemic chemotherapy for the treatment of brain metastases (Table 5) [7, 8, 19, 20, 25–28]. There do not appear to be substantial differences in the median OS achieved with different temozolomide schedules and other experimental systemic chemotherapy regimens. However, because of the relatively small numbers of patients in some studies and variable prior treatment history, it is difficult to compare results across studies. None the less, the survival data from the present study are similar to those reported in other trials of systemic chemotherapy.

Table 5.

Summary of efficacy of systemic therapy in patients with brain metastases

| Study | Primary tumor type | Treatment | N | Disease control ratea (%) | OS (months) |

| Agarwala et al. [26] | Melanoma | TMZ, 5 days | 151 | 32 | 3.8 |

| DeCOG/ADO [25] | Melanoma | TMZ, alternating weekly | 45 | 15 | 4.3 |

| Bernardo et al. [19] | NSCLC | Vinorelbine + GEM + carboplatin | 20 | 70 | 8.3 |

| Cortes et al. [20] | NSCLC | PAC + cisplatin | 25 | 38b | 5.3 |

| Trudeau et al. [27] | Breast | TMZ, alternating weekly | 19 | 16 | Not reported |

| Christodoulou et al. [28] | Mixed | TMZ, 5 days + cisplatin | 32 | 47 | 5.5 |

| Abrey et al. [7] | Mixed | TMZ, 5 days | 34 | 50 | 6.6 |

| Christodoulou et al. [8] | Mixed | TMZ, 5 days | 24 | 21 | 4.5 |

| Present study | Melanoma | TMZ, alternating weekly | 53 | 32 | 3.3 |

| NSCLC | 53 | 26 | 5.7 | ||

| Breast | 51 | 20 | Not reached |

OS, overall survival; TMZ, temozolomide; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; GEM, gemcitabine; PAC, paclitaxel.

Disease control rate = complete response + partial response + stable disease.

Intracranial response rate.

In patients with BC, a variety of regimens have been investigated for the treatment of brain metastases including topotecan, temozolomide, cisplatin, and vinorelbine plus mitoxantrone [8, 22, 28–30]. Trials of single-agent topotecan in patients with metastatic BC demonstrated very modest clinical activity, and further trials using this agent were not recommended [31]. Single-agent temozolomide using the standard 5-day regimen did not produce any objective responses in patients with brain metastases from BC [27]. In the present study, although the disease control rate was lowest in the BC group, two patients achieved a PR. Overall, the results of the present study indicate that single-agent temozolomide is active, but it is probably not the optimal strategy for treating brain metastases, particularly for BC.

More favorable outcomes have been achieved when temozolomide was combined with radiotherapy, and there is evidence to indicate that temozolomide may have a radiosensitizing effect [32, 33]. Studies combining temozolomide with WBRT reported response rates ranging from 55% to 96% with median survival ranging from 15 to 36 weeks [34]. In a phase II trial of temozolomide (75 mg/m2/day) administered concurrently with WBRT for 4 weeks followed by six cycles of 200 mg/m2/day × 5 days every 28-day cycle in patients with brain metastases from breast and lung cancer, Antonadou et al. [35] reported a median survival of 36 weeks. More recently, a phase II trial of temozolomide plus WBRT followed by temozolomide maintenance (standard 5-day schedule) reported a median OS of 52 weeks in patients with brain metastases from NSCLC and other solid tumors, including BC [30]. Similarly, Addeo et al. [36] demonstrated that concomitant WBRT and temozolomide plus the standard 5-day maintenance temozolomide schedule was well tolerated and produced an encouraging objective response rate (45%) and a significant improvement in quality of life. The ongoing SWS-SAKK-70/03 and RTOG-0320 randomized trials are investigating WBRT with or without dose-dense temozolomide in patients with brain metastases from NSCLC. It is hoped that these studies will provide further clarification of the benefit of combining WBRT with a dose-dense temozolomide regimen.

Combinations of WBRT with chemotherapy have also been reported to yield high response rates in patients with brain metastases from BC; however, this often fails to translate into improved survival. In one study, WBRT plus topotecan resulted in a 72% objective response rate, but median OS was only 17 weeks [22]. Similar results were obtained in a recent phase III trial of WBRT with or without efaproxiral in patients with brain metastases from breast or lung cancer; median OS in the efaproxiral plus WBRT arm was 23 and 18 weeks for breast and lung cancer patients, respectively [37].

Clinical strategies to control brain metastases must also consider the biologic characteristics of the tumor and control of extracranial disease. In fact, the long-term survival (>20 months) achieved in patients with brain metastases from HER2-positive BC who were treated with trastuzumab-based therapy may be attributed to better control of extracranial disease [38, 39]. Several studies have also shown that small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g. lapatinib, gefitinib, and erlotinib), which have systemic activity in tumors with specific molecular phenotypes, are a viable option for treating brain metastases [40–42]. Lapatinib has demonstrated activity against brain metastases from HER2-positive BC, whereas gefitinib and erlotinib were particularly effective in patients with brain metastases from primary lung tumors harboring epidermal growth factor receptor amplifications or mutations [40, 42]. Combining temozolomide with other therapeutic agents that have demonstrated activity against systemic metastatic disease could potentially enhance the clinical benefit in pretreated patients with brain metastases.

In summary, this alternating weekly (7/14-day), dose-dense temozolomide regimen is well tolerated and has antitumor activity in patients with brain metastases from melanoma, BC, and NSCLC and compares favorably with other temozolomide-dosing schedules, particularly in patients with melanoma; however, single-agent temozolomide is probably not the optimal therapeutic strategy, especially in patients with NSCLC or BC. The combination of temozolomide with WBRT or other agents with CNS and systemic antitumor activity may improve clinical outcome of patients with brain metastases. Larger studies of dose-dense temozolomide plus concomitant WBRT are ongoing.

funding

Schering-Plough International; Oncologia Ca'Granda Onlus (OCGO) Fondazione and Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) to S.S. and I.S. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Schering Plough.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jerome Sah and Jeffrey Riegel, of ProEd Communications, Inc.®, for medical editorial assistance with this manuscript. We also thank Stefania Gori for critical scientific revision of this manuscript and Massimo Corsaro, Simona Orecchia, and Hazem Osman from Schering-Plough for scientific and administrative support during the trial.

List of other participants: Agostara Biagio, Ospedale Oncologico M. Ascoli, Palermo; Boiardi Amerigo, Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milano; Aitini Enrico, Ospedale Carlo Poma, Mantova; Cartenì Giacomo, Azienda Ospedaliera Cardarelli, Napoli; Daniele Bruno, Unità Operativa Oncologia Medica, Benevento; Desogus Alberto, Ospedale Oncologico ‘Businco’, Cagliari; Dogliotti Luigi, Azienda Ospedaliera San Luigi, Orbassano (Torino); Ferrau' Francesco, Ospedale San Vincenzo, Taormina; Foa Paolo, Azienda Ospedaliera S. Paolo, Milano; Iacobelli Stefano, Presidio Ospedaliero S.S. Annunziata, Chieti; Iaffaioli Vincenzo, Istituto dei Tumori Fondazione Pascale, Napoli; Lelli Giorgio, Arcispedale Sant'Anna, Ferrara; Maiello Evaristo, Ospedale Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, San Giovanni Rotondo (Foggia); Manzione Luigi, Ospedale San Carlo, Potenza; Nardi Mario, Azienda Ospedaliera Bianchi Melacrino Morelli, Reggio Calabria; Pinotti Graziella, Ospedale Di Circolo Fondazione Macchi, Varese; Romanini Antonella, Ospedale Santa Chiara, Pisa; Rosso Riccardo, Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Genova; Soffietti Riccardo, Azienda Ospedaliera S. Giovanni Battista, Torino.

Presented in part in: Danova M, Bajetta E, Crinò L et al. Multicenter phase II study of temozolomide therapy for brain metastases in patients with malignant melanoma, breast cancer, or non-small cell lung cancer: Final results. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26 (Suppl): 97s (Abstr 2032).

The authors indicate no potential conflict of interest.

Contributors—conception and design: S. Siena; provision of study materials or patients: S. Siena, LC, MD, SDP, SC, S. Salvagni, IS, MV, and EB; collection and assembly of data: S. Siena, LC, MD, SDP, SC, S. Salvagni, IS, MV, and EB; data analysis and interpretation: S. Siena and MD; manuscript writing: S. Siena, MD, and IS; final approval of manuscript: S. Siena, LC, MD, SDP, SC, S. Salvagni, IS, MV, and EB.

References

- 1.Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Sloan AE, Davis FG, et al. Incidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2865–2872. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schouten LJ, Rutten J, Huveneers HA, Twijnstra A. Incidence of brain metastases in a cohort of patients with carcinoma of the breast, colon, kidney, and lung and melanoma. Cancer. 2002;94:2698–2705. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eichler AF, Loeffler JS. Multidisciplinary management of brain metastases. Oncologist. 2007;12:884–898. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-7-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lagerwaard FJ, Levendag PC, Nowak PJ, et al. Identification of prognostic factors in patients with brain metastases: a review of 1292 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:795–803. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00442-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaspar L, Scott C, Rotman M, et al. Recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) of prognostic factors in three Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) brain metastases trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:745–751. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaspar LE, Scott C, Murray K, Curran W. Validation of the RTOG recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) classification for brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:1001–1006. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00547-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abrey LE, Olson JD, Raizer JJ, et al. A phase II trial of temozolomide for patients with recurrent or progressive brain metastases. J Neurooncol. 2001;53:259–265. doi: 10.1023/a:1012226718323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christodoulou C, Bafaloukos D, Kosmidis P, et al. Phase II study of temozolomide in heavily pretreated cancer patients with brain metastases. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:249–254. doi: 10.1023/a:1008354323167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedde J-P, Ko Y, Metzler U, et al. A phase I/II trial of topotecan and radiation therapy for CNS-metastases of patients with solid tumors. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;22(Suppl):111. (Abstr 444) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danson SJ, Middleton MR. Temozolomide: a novel oral alkylating agent. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2001;1:13–19. doi: 10.1586/14737140.1.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newlands ES, O'Reilly SM, Glaser MG, et al. The Charing Cross Hospital experience with temozolomide in patients with gliomas. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:2236–2241. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yung WK, Prados MD, Yaya-Tur R, et al. Multicenter phase II trial of temozolomide in patients with anaplastic astrocytoma or anaplastic oligoastrocytoma at first relapse. Temodal Brain Tumor Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2762–2771. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bignami M, O'Driscoll M, Aquilina G, Karran P. Unmasking a killer: DNA O(6)-methylguanine and the cytotoxicity of methylating agents. Mutat Res. 2000;462:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roos WP, Batista LF, Naumann SC, et al. Apoptosis in malignant glioma cells triggered by the temozolomide-induced DNA lesion O6-methylguanine. Oncogene. 2007;26:186–197. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolcher AW, Gerson SL, Denis L, et al. Marked inactivation of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase activity with protracted temozolomide schedules. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:1004–1011. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandes AA, Tosoni A, Cavallo G, et al. Temozolomide 3 weeks on and 1 week off as first-line therapy for recurrent glioblastoma: phase II study from gruppo italiano cooperativo di neuro-oncologia (GICNO) Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1155–1160. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wick A, Felsberg J, Steinbach JP, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of temozolomide in an alternating weekly regimen in patients with recurrent glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3357–3361. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernardo G, Cuzzoni Q, Strada MR, et al. First-line chemotherapy with vinorelbine, gemcitabine, and carboplatin in the treatment of brain metastases from non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase II study. Cancer Invest. 2002;20:293–302. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120001173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cortes J, Rodriguez J, Aramendia JM, et al. Front-line paclitaxel/cisplatin-based chemotherapy in brain metastases from non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncology. 2003;64:28–35. doi: 10.1159/000066520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franciosi V, Cocconi G, Michiara M, et al. Front-line chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide for patients with brain metastases from breast carcinoma, nonsmall cell lung carcinoma, or malignant melanoma: a prospective study. Cancer. 1999;85:1599–1605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedde JP, Neuhaus T, Schuller H, et al. A phase I/II trial of topotecan and radiation therapy for brain metastases in patients with solid tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:839–844. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong ET, Berkenblit A. The role of topotecan in the treatment of brain metastases. Oncologist. 2004;9:68–79. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-1-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, Winkler A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer. 1981;47:207–214. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810101)47:1<207::aid-cncr2820470134>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schadendorf D, Hauschild A, Ugurel S, et al. Dose-intensified bi-weekly temozolomide in patients with asymptomatic brain metastases from malignant melanoma: a phase II DeCOG/ADO study. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1592–1597. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agarwala SS, Kirkwood JM, Gore M, et al. Temozolomide for the treatment of brain metastases associated with metastatic melanoma: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2101–2107. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trudeau ME, Crump M, Charpentier D, et al. Temozolomide in metastatic breast cancer (MBC): a phase II trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada–Clinical Trials Group (NCIC-CTG) Ann Oncol. 2006;17:952–956. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christodoulou C, Bafaloukos D, Linardou H, et al. Temozolomide (TMZ) combined with cisplatin (CDDP) in patients with brain metastases from solid tumors: a Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group (HeCOG) Phase II study. J Neurooncol. 2005;71:61–65. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-9176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onyenadum A, Gogas H, Markopoulos C, et al. Mitoxantrone plus vinorelbine in pretreated patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Chemother. 2007;19:582–589. doi: 10.1179/joc.2007.19.5.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kouvaris JR, Miliadou A, Kouloulias VE, et al. Phase II study of temozolomide and concomitant whole-brain radiotherapy in patients with brain metastases from solid tumors. Onkologie. 2007;30:361–366. doi: 10.1159/000102557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorusso V, Galetta D, Giotta F, et al. Topotecan in the treatment of brain metastases. A phase II study of GOIM (Gruppo Oncologico dell'Italia Meridionale) Anticancer Res. 2006;26:2259–2263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang JE, Khuntia D, Robins HI, Mehta MP. Radiotherapy and radiosensitizers in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2007;5:894–902. 907–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Nifterik KA, van den Berg J, Stalpers LJ, et al. Differential radiosensitizing potential of temozolomide in MGMT promoter methylated glioblastoma multiforme cell lines. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1246–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.07.2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langer CJ, Mehta MP. Current management of brain metastases, with a focus on systemic options. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6207–6219. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antonadou D, Paraskevaidis M, Sarris G, et al. Phase II randomized trial of temozolomide and concurrent radiotherapy in patients with brain metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3644–3650. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Addeo R, Caraglia M, Faiola V, et al. Concomitant treatment of brain metastasis with whole brain radiotherapy [WBRT] and temozolomide [TMZ] is active and improves quality of life. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suh JH, Stea B, Nabid A, et al. Phase III study of efaproxiral as an adjunct to whole-brain radiation therapy for brain metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:106–114. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gori S, Rimondini S, De Angelis V, et al. Central nervous system metastases in HER-2 positive metastatic breast cancer patients treated with trastuzumab: incidence, survival, and risk factors. Oncologist. 2007;12:766–773. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-7-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirsch DG, Ledezma CJ, Mathews CS, et al. Survival after brain metastases from breast cancer in the trastuzumab era. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2114–2116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.249. author reply 2116–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ceresoli GL, Cappuzzo F, Gregorc V, et al. Gefitinib in patients with brain metastases from non-small-cell lung cancer: a prospective trial. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1042–1047. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin NU, Dieras VD, Paul D, et al. EGF105084, a phase II study of lapatinib for brain metastases in patients (pts) with HER2+ breast cancer following trastuzumab (H) based systemic therapy and cranial radiotherapy (RT) J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:35. doi: 10.1007/s10147-012-0444-2. (Abstr 1012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pan M, Santamaria M, Wollman DB. CNS response after erlotinib therapy in a patient with metastatic NSCLC with an EGFR mutation. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:603–607. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]