Abstract

Background: The antiestrogen tamoxifen may have partial estrogen-like effects on the postmenopausal uterus. Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) are increasingly used after initial tamoxifen in the adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal early breast cancer due to their mechanism of action: a potential benefit being a reduction of uterine abnormalities caused by tamoxifen.

Patients and methods: Sonographic uterine effects of the steroidal AI exemestane were studied in 219 women participating in the Intergroup Exemestane Study: a large trial in postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive (or unknown) early breast cancer, disease free after 2–3 years of tamoxifen, randomly assigned to continue tamoxifen or switch to exemestane to complete 5 years adjuvant treatment. The primary end point was the proportion of patients with abnormal (≥5 mm) endometrial thickness (ET) on transvaginal ultrasound 24 months after randomisation.

Results: The analysis included 183 patients. Two years after randomisation, the proportion of patients with abnormal ET was significantly lower in the exemestane compared with tamoxifen arm (36% versus 62%, respectively; P = 0.004). This difference emerged within 6 months of switching treatment (43.5% versus 65.2%, respectively; P = 0.01) and disappeared within 12 months of treatment completion (30.8% versus 34.7%, respectively; P = 0.67).

Conclusion: Switching from tamoxifen to exemestane significantly reverses endometrial thickening associated with continued tamoxifen.

Keywords: adjuvant treatment, aromatase inhibitors, breast cancer, endometrium, exemestane, tamoxifen

introduction

Tamoxifen, for many years the ‘gold-standard’ endocrine treatment of breast cancer, is associated with an increased incidence of uterine abnormalities such as endometrial hyperplasia, polyps, cysts and fibroids and an increased risk of uterine cancer and sarcoma [1, 2]. These effects are thought to be related to the agonistic pathway elicited by tamoxifen on uterine estrogen receptors.

Data from the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group overview [3] indicate that the incidence of uterine cancer in patients with primary breast cancer receiving adjuvant tamoxifen is increased by a factor of ∼3 (1.9 versus 0.6 per 1000 per year). Although the absolute risk of endometrial cancer in patients under tamoxifen is low, screening programmes using transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) have been proposed [4]. In postmenopausal women, an endometrial lining measuring <5 mm is considered an accurate cut-off in excluding endometrial disease. Abnormal endometrial thickness (ET) i.e. ≥5 mm occurs in 8% of asymptomatic postmenopausal women [5] but has been reported in up to 85% of asymptomatic postmenopausal breast cancer patients on tamoxifen [6–13]. Following tamoxifen discontinuation, ET tends to decrease [14] but in some patients abnormal thickness may be long lasting; two follow-up studies [15, 16] have reported abnormal thickness in 45% and 42% of patients after 12 and 30 months, respectively, from withdrawal of tamoxifen.

The relationship between ET and the presence of endometrial pathological abnormality varies, but most investigators agree that endometrial thickening has low specificity and low positive predictive value for histological abnormalities in tamoxifen-treated patients [9]. This effect is mainly due to tamoxifen-induced subepithelial stromal proliferation, entrapping gland lumens leading to cystic changes. This anatomical condition mimics endometrial hyperplasia at ultrasound, while the epithelium remains normal or atrophic in the majority of cases [17]. Such false-positive results, in a population known to be at risk for uterine cancer, may generate stress and anxiety among patients and clinicians and lead to unnecessary invasive procedures. Based on the limited availability of efficacious or cost-effective diagnostic tests, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommends routine yearly gynaecological examination with further evaluation limited to patients presenting with bleeding or vaginal discharge [18]. Despite this, active surveillance for endometrial pathological abnormalities is commonly practised among tamoxifen users [19].

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) are a class of compounds that inhibit the synthesis of estrogens from androgens. Third-generation nonsteroidal inhibitors (anastrozole and letrozole) and the steroidal inactivator exemestane induce >98% inhibition of whole-body aromatisation [20, 21] and have been shown to outperform tamoxifen as adjuvant therapy in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer [22–24]. Additionally, due to the lack of estrogenic activity, a potential advantage of their use in this setting might be the lack of adverse uterine effects.

The Intergroup Exemestane Study (IES) compared continued tamoxifen with a switch to exemestane after 2–3 years of tamoxifen to complete a total of 5 years treatment in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer. Improvements in disease-free and overall survival in patients who switched to exemestane have been reported [24, 25]. Improvements were achieved without compromising overall quality of life [26], and with limited detrimental effects on skeletal health [27]. While major gynaecological safety data were collected, uterine effects in asymptomatic patients could be overlooked. A sub-protocol was therefore designed to allow prospective assessment of uterine changes in a subset of IES participants. As all patients were postmenopausal and had been exposed to tamoxifen for 2–3 years, a high incidence of baseline abnormality was expected. Results of this sub-protocol up to 24 months after treatment, along with the incidence of gynaecological events in the main trial, are presented here.

patients and methods

study design

IES was an international double-blind phase III randomised trial conducted by the International Collaborative Cancer Group (ICCG) under the auspices of the Breast International Group. From 1998 to 2003, 4724 postmenopausal women previously diagnosed with estrogen receptor-positive or estrogen receptor-unknown breast cancer who received adequate local and adjuvant treatments and remained disease free after 2–3 years of tamoxifen were centrally randomly assigned to either continue tamoxifen (20 mg/day) or switch to exemestane (25 mg/day) to complete a total of 5 years adjuvant endocrine therapy [24, 25]. The endometrial sub-protocol was implemented in 26 of the 366 IES centres. The institutional review board or local ethics committee at each participating centre approved the sub-protocol.

eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria for the main study have been previously described [24]; briefly, patients were postmenopausal (≥55 years of age with amenorrhoea for >2 years or amenorrhoea for >1 year at the time of diagnosis) and had received adjuvant tamoxifen for at least 2 years but not >3 years and 1 month. Patients were excluded if they had used hormone replacement therapy (HRT) within 4 weeks before randomisation and if they were taking any other form of hormone therapy other than tamoxifen. Additionally, patients were eligible for the endometrial sub-protocol if they had an intact uterus and signed informed consent to participate in the sub-protocol. Patients with abnormal vaginal bleeding during the previous year were eligible if uterine malignancy had been adequately excluded by hysteroscopy and/or biopsy.

endometrial assessments

Patients underwent baseline TVUS in the month before randomisation. Follow-up examinations (including TVUS) were repeated in parallel to main study visits (±4 weeks) at months 6, 12, 24 and end of treatment (EoT). TVUS examinations at 12 and 24 months after treatment completion were added following a protocol amendment (May 2001). TVUS was also carried out at disease recurrence. The EoT examination could be omitted if within 6 months of a previous endometrial assessment.

ET and uterine volume were measured from the TVUS. The anteroposterior measurement of ET was obtained from the longitudinal axis view at the widest point of the endometrial–myometrial interface, recording the maximum width of the double layer (excluding anechoic endometrial fluid collection). The maximum longitudinal diameter (length) of the uterus was measured from the internal os to the fundus (D1). The largest diameters in the transverse (D2) and the anteroposterior (D3) planes were also recorded. Uterine volume was estimated as (D1 × D2 × D3)/2. Hard copies of all available TVUS scans were subject to independent review by a gynaecologist experienced in pelvic sonography.

study end points

The primary end point was the proportion of patients with ET ≥5 mm at 24 months after randomisation. Secondary end points included the proportion of patients with ET ≥5 mm at 6 and 12 months after randomisation and 12 and 24 months after EoT, ET as a continuous variable and uterine volume. Incidence of gynaecological symptoms, gynaecological procedures and serious gynaecological adverse events (AEs) were recorded as part of the main trial.

statistical considerations

The sample size was based on estimates of the proportion of postmenopausal patients with ET in women undergoing tamoxifen treatment and those undergoing no hormonal therapy. Target accrual was initially 114 patients to detect a 30% absolute difference in the proportion of patients with ET ≥5 mm 24 months after randomisation (from 50% in the tamoxifen group to 20% in the exemestane group) with 90% power and a two-sided significance level of 0.05.

Data on ET following cessation of tamoxifen [16] published in 2000 led the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) to re-evaluate these estimates and the sample size was increased to 176 patients (200 allowing for a 15% attrition rate) in order to detect a 25% difference in the proportion of patients with ET ≥5 mm (i.e. from 55% in the tamoxifen group to 30% in the exemestane group). The study has 73% power to detect such a difference based on the number of patients assessable for the primary end point.

Analyses were conducted on complete data, cleaned and processed by the ICCG Coordinating Data Centre (CDC), available on 26 November 2006 by use of Stata (version 9.2).

The primary comparison was based on patients who received at least 24 months of allocated treatment and underwent TVUS 22–26 months after randomisation (denoted assessable for primary end point population). All other analyses were carried out on all randomised patients on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis. Participants were censored at hysterectomy and relapse. TVUS was only included at particular visits if it fell within the predefined windows based on the date of TVUS. If the EoT examination was not carried out as it fell within 6 months of a previous visit, the 24-month TVUS was included as the EoT assessment.

Sensitivity analyses were carried out on the following populations: eligible patients only (i.e. excluding patients subsequently found to be ineligible for either the main trial or the sub-protocol); all treated patients; patients evaluable for the primary endpoint; and all patients assessed within tighter visit windows. These sensitivity analyses (not shown) confirmed the robustness of the primary analysis.

Differences in proportions between the two groups were compared using chi-square and Fisher's exact test as appropriate. One-sample paired t-tests were used to assess within-group changes in ET and uterine volume at each time point expressed as changes from baseline. Differences in mean changes (exemestane–tamoxifen) of these measures (where negative values indicate greater change in the tamoxifen group than in the exemestane group) were compared using two-sample t-tests. All analyses used a 5% significance level.

To account for the longitudinal nature of the ET data, a linear mixed model was fitted adjusting for randomised treatment, baseline ET and weight and timing of TVUS with consideration given to interactions and polynominal effects. The overall interpretation of the results was not altered. For simplicity, and to aid clinical review, results based on changes from baseline are reported.

The incidences of gynaecological and menopausal AEs in the main study were compared by treatment group. On-treatment analysis included AEs occurring between randomisation and 30 days after last study treatment, censoring patients at time of relapse or second primary cancer. AEs are presented if the incidence was ≥10% in either treatment group, if the difference between the groups was >1% or if the difference between the treatment groups was significant at the 1% level.

role of the funding source

The sub-protocol was developed by the IES TSC. The sponsor provided funding, had limited input in the study design and gave organisational and monitoring support to the CDC where the database was independently held. Transfers of frozen copies of the database were provided to the sponsor for submission to the regulatory authorities and fulfilment of regulatory responsibilities. All members of the TSC, including sponsor representatives, were given the opportunity to critically review the manuscript; however, editorial control was retained by the members of the steering committee independent of the sponsor. All analyses were conducted by the CDC in agreement with the trial's Independent Data Monitoring Committee and TSC. The corresponding author had access to all study data and took final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

results

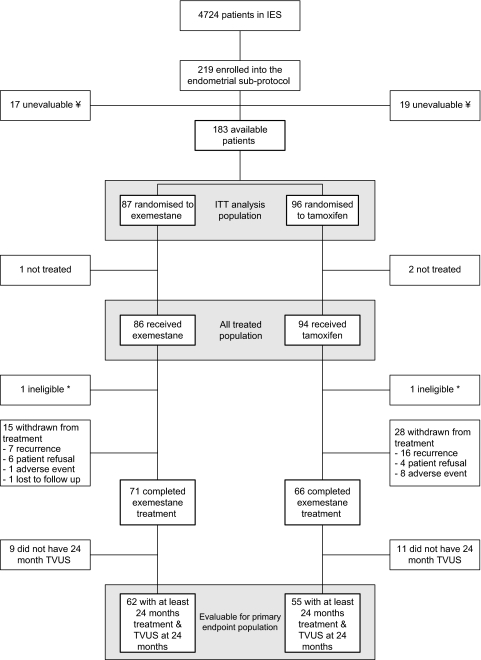

From 1999 to 2001, 219 patients (104 exemestane and 115 tamoxifen) were enrolled into the endometrial sub-protocol (Figure 1). Monitoring carried out by the sponsor highlighted a number of issues at one endometrial sub-protocol satellite site and the data were considered unreliable. All 36 patients from this site (17 exemestane and 19 tamoxifen) were therefore excluded from the analysis leaving 183 patients (87 exemestane and 96 tamoxifen) in the ITT population (including three patients who did not receive any treatment). Two patients were subsequently found to be protocol violators because they did not have baseline TVUS carried out within 30 days before randomisation but are included in the analyses presented here. The primary comparison included 117 assessable patients.

Figure 1.

Consolidated standards of reporting trials diagram. ¥Monitoring carried out by the sponsor highlighted a number of issues regarding the conduct of the endometrial sub-protocol at a satellite site. Based on these findings, patients at this satellite site have been excluded from the endometrial sub-protocol analysis (n = 36). *TVUS not carried out ≤30 days before randomisation. These patients were included in the analyses presented here. TVUS, transvaginal ultrasound; IES, Intergroup Exemestane Study; ITT, intention-to-treat.

TVUS scans for 89.7% study assessments were independently reviewed and, following a query to the local investigator, 11.3% of original ET measurements were amended.

At baseline, the two groups were well balanced with regard to demographic characteristics and prior treatment (Table 1), ET and uterine volume (Table 2). Gynaecological symptoms during tamoxifen treatment before randomisation were reported in 20% of women (18 exemestane and 19 tamoxifen). The overall median ET at baseline (randomisation) was 6.0 mm (inter-quartile range 3.5–9.0) and 62.6% of patients had increased (≥5 mm) ET.

Table 1.

Patient and tumour characteristics at study entry

| Exemestane (N = 87) |

Tamoxifen (N = 96) |

|||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| <60 | 37 | 42.5 | 41 | 42.7 |

| 60–69 | 35 | 40.2 | 42 | 43.8 |

| 70+ | 15 | 17.2 | 13 | 13.5 |

| Nodal status | ||||

| Negative | 47 | 54.0 | 56 | 58.3 |

| 1–3 nodes positive | 26 | 29.9 | 21 | 21.9 |

| 4+ nodes positive | 11 | 12.6 | 16 | 16.7 |

| Missing/unknown | 3 | 3.5 | 3 | 3.1 |

| Hormone receptor status | ||||

| ER positive; PgR positive | 35 | 40.2 | 41 | 42.7 |

| ER positive; PgR negative/unknown | 35 | 40.2 | 25 | 26.0 |

| ER unknown; PgR positive/unknown | 12 | 13.8 | 21 | 21.9 |

| ER negative; PgR positive | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.1 |

| ER negative; PgR negative/unknown | 5 | 5.8 | 7 | 7.3 |

| Tumour size | ||||

| <2 cm | 35 | 40.2 | 34 | 35.4 |

| 2–5 cm | 47 | 54.0 | 53 | 55.2 |

| >5 cm | 3 | 3.5 | 5 | 5.2 |

| Missing | 2 | 2.3 | 4 | 4.2 |

| Tumour grade | ||||

| G1 | 10 | 11.5 | 14 | 14.6 |

| G2 | 38 | 43.7 | 49 | 51.0 |

| G3 | 14 | 16.1 | 17 | 17.7 |

| Undifferentiated | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Not assessable | 8 | 9.2 | 3 | 3.1 |

| Missing/unknown/not assessed | 16 | 18.4 | 12 | 12.5 |

| Histological type | ||||

| Infiltrating lobular | 13 | 14.9 | 8 | 8.3 |

| Infiltrating ductal | 65 | 74.7 | 77 | 80.2 |

| Other | 9 | 10.3 | 11 | 11.5 |

| Type of surgery | ||||

| Mastectomy | 64 | 73.6 | 64 | 66.7 |

| Wide local excision | 17 | 19.5 | 24 | 25.0 |

| Other | 6 | 6.9 | 8 | 8.3 |

| Prior chemotherapy use | 43 | 49.4 | 50 | 52.1 |

| Duration of prior tamoxifen (months) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 26.8 (25.1–31.7) | 28.1 (25.6–32.4) | ||

| Weight at baseline (kg) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 72.0 (14.4) | 72.8 (11.6) | ||

| Years since last menses | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 13.0 (4.5–17.5) | 11.8 (5.3–16.3) | ||

| Prior HRT use | 15 | 17.2 | 11 | 11.5 |

ER, estrogen receptor; PgR, progesterone receptor; IQR, inter-quartile range; SD, standard deviation; HRT, hormone replacement therapy.

Table 2.

ET and uterine volume at baseline

| Exemestane | Tamoxifen | |

| ET (mm) | ||

| N | 84 | 95 |

| Median | 5.8 | 6.0 |

| IQR | 3.2–9.4 | 4.0–9.0 |

| Uterine volume (cm3) | ||

| N | 80 | 92 |

| Median | 38.4 | 44.2 |

| IQR | 24.9–61.6 | 31.1–60.6 |

ET, endometrial thickness; IQR, inter-quartile range.

Twenty-four-month TVUS scans were available for 117 (85%) of randomised patients who received at least 2 years of allocated treatment. ET ≥5 mm was found in 35.5% [95% confidence interval (CI) 23.6% to 47.4%] of patients switched to exemestane and in 61.8% (95% CI 49.0% to 74.7%) of those continuing tamoxifen (P = 0.004; Table 3). The difference in the proportion of patients with abnormal ET had emerged by 6 months after randomisation (43.5% exemestane versus 65.2% tamoxifen; P = 0.01) and persisted throughout the protocol treatment period. Within 12 months of treatment completion, there were no differences in the proportion of patients with abnormal ET (30.8% exemestane versus 34.7% tamoxifen; P = 0.67).

Table 3.

Proportion of patients with ET ≥5 mm (ITT population)

| Visit | Exemestane |

Tamoxifen |

Chi-square P value | ||

| N | ET ≥5 mm (%) | N | ET ≥5 mm (%) | ||

| Baseline | 84 | 52 (61.9) | 95 | 60 (63.2) | 0.86 |

| 6 months | 69 | 30 (43.5) | 69 | 45 (65.2) | 0.01 |

| 12 months | 61 | 19 (31.2) | 61 | 35 (57.4) | 0.004 |

| 24 months | 62 | 22 (35.5) | 55 | 34 (61.8) | 0.004a |

| EoT | 54 | 15 (27.8) | 53 | 33 (62.3) | <0.001 |

| EoT + 12 months | 52 | 16 (30.8) | 49 | 17 (34.7) | 0.67 |

| EoT + 24 months | 46 | 16 (34.8) | 38 | 13 (34.2) | 0.96 |

Proportion of patients with ET ≥5 mm at 24 months in the evaluable for primary end point population was identical to those in the ITT population.

ET, endometrial thickness; EoT, end of treatment.

A within-patient transition from abnormal ET at baseline to normal thickness after 24 months of allocated treatment was observed in 20 patients (53%) switched to exemestane and in six patients (19%) continuing tamoxifen (Table 4). Among patients with normal ET at baseline, four patients (17%) in the exemestane group and eight (35%) in the tamoxifen group developed endometrial thickening. Additional gynaecological investigations were not mandated by the protocol; therefore, we cannot correlate these changes in endometrial thickening with hysteroscopy or biopsy results.

Table 4.

Transition between abnormal (≥5 mm) and normal ET after 24 months of randomised treatment

| Exemestane |

Tamoxifen |

|||||

| Na | Normal ET at 24 months, n (%) | Abnormal ET (≥5 mm) at 24 months, n (%) | N | Normal ET at 24 months, n (%) | Abnormal ET (≥5 mm) at 24 months, n (%) | |

| Normal ET at baseline | 23 | 19 (83) | 4 (17) | 23 | 15 (65) | 8 (35) |

| ET (≥5 mm) at baseline | 38 | 20 (53) | 18 (47) | 32 | 6 (19) | 26 (81) |

Baseline TVUS unavailable for one patient.

ET, endometrial thickness; TVUS, transvaginal ultrasound.

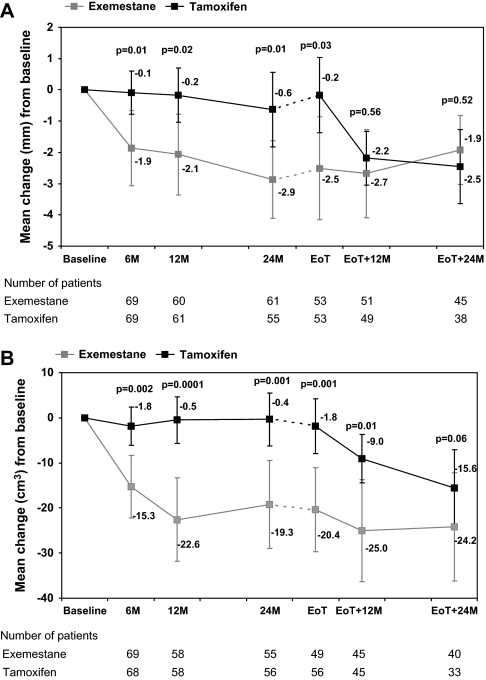

Patients who switched to exemestane had a rapid decrease of ET in the first 6 months (mean change from baseline −1.9 mm; 95% CI −3.1 to −0.6; P = 0.003; Figure 2A). Further, less pronounced reduction was observed between 6 and 24 months (mean change 24–6 months = −0.4 mm; 95% CI −1.3 to 0.5; P = 0.37). Patients who continued on tamoxifen had no significant changes of ET from baseline to 24 months after randomisation. At 12 and 24 months after EoT, no difference was observed between the two treatment groups in mean change from baseline.

Figure 2.

(A) Mean change [95% confidence interval (CI)] in endometrial thickness from baseline. (B) Mean change (95% CI) in uterine volume from baseline.

Uterine volume was significantly reduced after 6 months in patients switching to exemestane (mean change from baseline −15.3 cm3; 95% CI −22.4 to −8.2; P = 0.0001) while remaining similar in the tamoxifen group (mean change = −1.8 cm3; 95% CI −6.2 to 2.5; P = 0.40; Figure 2B). In consequence, 6 months after randomisation, the difference in mean change between the two treatment groups (−13.5 cm3; 95% CI −21.7 to −5.2) was highly significant (P = 0.002). Again, the observed difference was maintained after 12 and 24 months, with difference in mean changes of −22.1 cm3 (95% CI −32.8 to −11.4; P = 0.0001) and −18.9 cm3 (95% CI −30.4 to −7.5; P = 0.001), respectively. Mean change from baseline in uterine volume continued to differ between the treatment groups at 12 months after EoT (−16 cm3; 95% CI −28.7 to −3.3; P = 0.01) but no significant difference was seen 24 months after EoT.

Eight patients in the endometrial substudy (exemestane two and tamoxifen six) underwent hysterectomy (±salpingo-oophorectomy): one (tamoxifen) due to second primary ovarian cancer, three due to cervical cancer (exemestane two, tamoxifen one) and four (on tamoxifen) due to other gynaecological symptoms such as complex endometrial hyperplasia, fibroids and polyps. No endometrial cancers were reported in the sub-protocol population.

In the main IES trial, endometrial hyperplasia, uterine polyps/fibroids, uterine dilation and curettage and vaginal bleeding had a significantly higher incidence on treatment in the tamoxifen group compared with the exemestane group (Table 5). Twenty-five endometrial cancers have been reported: nine in the exemestane group (four on treatment and five after treatment) and 16 in the tamoxifen group (nine on treatment and seven after treatment) although this difference was not significant [24].

Table 5.

Number of gynaecological/menopausal adverse events reported on treatment (in whole IES population)

| Adverse event | Exemestane (N = 2320) |

Tamoxifen (N = 2338) |

P value | ||||||

| All CTC grades | UG | Total | % | All CTC grades | UG | Total | % | ||

| Gynaecological symptoms | 128 | 128 | 256 | 11.0 | 156 | 210 | 366 | 15.7 | <0.001 |

| Serious gynaecological symptoms | 70 | 55 | 125 | 5.4 | 90 | 103 | 193 | 8.3 | <0.001 |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.0 | 1 | 19 | 20 | 0.9 | <0.001 |

| Genital pruritis female | 19 | 0 | 19 | 0.8 | 21 | 7 | 28 | 1.2 | 0.2 |

| Hot flashes | 955 | 2 | 957 | 41.3 | 901 | 2 | 903 | 38.6 | 0.07 |

| Hysterectomy | 0 | 17 | 17 | 0.7 | 0 | 25 | 25 | 1.1 | 0.22 |

| Uterine D&C | 0 | 12 | 12 | 0.5 | 0 | 29 | 29 | 1.2 | 0.01 |

| Uterine polyps/fibroids | 1 | 23 | 24 | 1.0 | 1 | 64 | 65 | 2.8 | <0.001 |

| Vaginal discharge | 53 | 12 | 65 | 2.8 | 79 | 12 | 91 | 3.9 | 0.04 |

| Vulvovaginal dryness | 53 | 2 | 55 | 2.4 | 47 | 4 | 51 | 2.2 | 0.67 |

| Metrorrhagia/vaginal bleeding | 80 | 23 | 103 | 4.4 | 116 | 42 | 158 | 6.8 | 0.002 |

| Vaginal prolapse/uterine prolapse | 4 | 23 | 27 | 1.2 | 2 | 11 | 13 | 0.6 | 0.02 |

| Vaginitis/vaginitis atrophic/vaginal candidiasis/vaginal infection | 13 | 27 | 40 | 1.7 | 12 | 28 | 40 | 1.7 | 0.97 |

Serious gynaecological events and menopausal symptoms are presented if the incidence is ≥10% in either treatment group, if the difference between the groups is >1% or if the difference between treatment groups resulted in a P value of <0.01. Patients with prior hysterectomy were excluded from the denominator for uterine polyps, fibroids, D&C, endometrial cancer and hysterectomy.

IES, Intergroup Exemestane Study; CTC, Common Toxicity Criteria; UG, ungraded (classed as between grades 2 and 3); D&C, dilation and curettage.

discussion

The IES endometrial sub-protocol is the first randomised, double-blind study to investigate the sonographic endometrial effects of a switch to exemestane after initial tamoxifen as an adjuvant treatment of early breast cancer. Participants in the sub-protocol were postmenopausal (median 12 years since last menses) and gynaecologically asymptomatic; despite this, at randomisation, 63% had abnormal ET on TVUS, likely as a consequence of the previous 2–3 years of tamoxifen treatment. Switching to exemestane resulted in a significant decrease of ET: 51% of patients with abnormal ET at baseline had normal ET 24 months after switch. Uterine volume also significantly decreased after the switch. Patients randomised to continue on tamoxifen had no significant variations in ET or uterine volume until the completion of adjuvant hormone therapy.

Studies on the endometrial effects of switching to an AI after tamoxifen have indicated a reduction of ET associated with AI treatment [28–32]. However, the follow-up period in these studies did not extend to the post-treatment phase, thus the effects of tamoxifen cessation (in the absence of an AI) could not be assessed and compared with those of switching to AIs. In the IES, patients were prospectively followed for 2 years after the end of adjuvant hormone treatment. After the end of treatment, patients in the tamoxifen group obtained reductions in ET and uterine volume paralleling those observed in the exemestane group during the treatment phase. This indicates that the reduction of ET and uterine volume seen after switching to exemestane is largely due to cessation of the stimulatory effect of tamoxifen. Approximately one-third of the patients in both groups still had abnormal ET up to 2 years after the end of treatment, which equates to >4 years after withdrawal of tamoxifen in the exemestane group. Other reports on the effects of tamoxifen discontinuation show a reduction in mean ET after cessation of treatment, with a significant proportion of patients still having abnormal findings during follow-up [14–16].

It is unknown how many of the patients participating in our study had abnormal ET before starting adjuvant hormone therapy. While in a population of healthy postmenopausal women not on HRT the incidence of abnormal ET is expected to be low, among women with breast cancer, other factors, such as relative hyperestrogenism, may play a role and lead to endometrial stimulation independently of tamoxifen. In the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial comparing 5 years of adjuvant treatment with tamoxifen with 5 years of anastrozole or the combination, the baseline incidence of endometrial thickening (ET > 5 mm) among 260 patients participating in the endometrial sub-protocol was 21% [33]. In another study on 146 breast cancer patients scheduled to start adjuvant tamoxifen, baseline TVUS revealed thickened endometrium (≥5 mm) in 30% of cases [34]. Post-treatment data have not been reported for these studies.

The management of early breast cancer patients on hormone therapy represents a significant proportion of the workload of many oncologists: gynaecological side-effects of tamoxifen are a frequent occurrence and often result in additional investigations, procedures and referrals. As switching to exemestane results in a significant reduction in gynaecological problems, this approach may have potentially important impact on clinical practice. A significant and rapid decrease of ET and uterine volume was seen with exemestane, whereas in patients continuing on tamoxifen, ultrasound abnormalities tend to persist until treatment completion. This is consistent with the reduction of gynaecological adverse events observed in the main IES trial.

funding

Pfizer Inc.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients for their participation in the sub-protocol; the investigators, nurses, data managers, radiographers and other support staff at local sites; the trial sponsor and the members of the Steering Committee and the Independent Data Monitoring Committee. We especially thank Jos Hollway (Imperial College Healthcare National Health Service Trust, UK) for expert independent review of all TVUS scans; Kelly Mousa and Emma Hudson (ICCG) for central coordination of the sub-protocol and Antonia Ridolfi and Lucy Kilburn (Clinical Trials and Statistics Unit, Institute of Cancer Research) for their contribution to the statistical analysis. Authors’ disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: GB has received consultancy fees and honoraria from Pfizer, Novartis and Astra Zeneca and research funding from Pfizer and Novartis. RCC has received honoraria and research funding from Pfizer. JMB has received honoraria, travel awards and research funding from Pfizer. Investigators who contributed patients to the IES endometrial sub-protocol: L. E. Fein, Centro Oncologico De Rosario, Argentina; R. Orti, Hospital Italiano De Buenos Aires, Argentina; A. Nunez De Pierro, Hospital Fernandez, Buenos Aires, Argentina; M. Bruno, Alvarez Hospital, Buenos Aires, Argentina; V. Tzekova, University Hospital Queen Joanna, Sofia, Bulgaria; Z. Krajina, University Hospital Osijek, Croatia; K. Diedrich, Medizinische Universitaet Luebeck, Germany; T. Laube, Henneberg-Kliniken, Germany; U. Rhein and U. Retzke (previous Principal Investigator), Zentralklinikum Suhl Ggmbh, Germany; A. R. Bian, Centro Oncologico Multizonale, Thiene, Italy; R. Rosso, Istituti Tumori Di Genova, Italy; P. Conte, Universita’ Degli Studi Di Modena-Cattedra Di Oncologia Medica, Italy; M. R. Sertoli, Istituti Tumori Di Genova-Oncologia Medica Universitaria, Italy; M. Merlano and D. Perroni, Ospedale S. Croce, Cuneo, Italy; L. Vesentini, Cariono, Azienda Ospedaliera Oirm Sant'Anna-Divisione C, Torino, Italy; J. Jassem, Medical University of Gdansk, Poland; M. Pawlicki, Centrum Onkologii, Krakow, Poland; B. Utracka-Hutka, Centrum Onkologii, Gliwice, Poland; H. Karnicka-Mlodkowska, Szpital Im. Pck W Gdynia, Poland; K. Drosik, Wojewodzki Osrodek Onkologii, Opole, Poland; N. Gutulescu, The Oncology Institute Bucharest, Romania; S. Susnjar and L. Mitrovic (previous PI), Institute for Oncology and Radiology of Serbia, Belgrade, Serbia and Montenegro; M. Wagnerova, L. Pasteur University Hospital, Kosice, Slovakia; J. Cervek, Institute Of Oncology, Ljubljana, Slovenia and A. Nejim, Airedale General Hospital, Steeton, UK.

References

- 1.Machado F, Rodriguez JR, Leon JP, et al. Tamoxifen and endometrial cancer. Is screening necessary? A review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2005;26:257–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen I. Endometrial pathologies associated with postmenopausal tamoxifen treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94:256–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neven P, Vergote I. Should tamoxifen users be screened for endometrial lesions? Lancet. 1998;351:155–157. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith-Bindman R, Kerlikowske K, Feldstein VA, et al. Endovaginal ultrasound to exclude endometrial cancer and other endometrial abnormalities. JAMA. 1998;280:1510–1517. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.17.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salazar EL, Paredes A, Calzada L. Endometrial thickness of postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2005;21:312–316. doi: 10.1080/09513590500430450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner FJ, Konje JC, Brown L, et al. Uterine surveillance of asymptomatic postmenopausal women taking tamoxifen. Climacteric. 1998;1:180–187. doi: 10.3109/13697139809085539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Love CD, Muir BB, Scrimgeour JB, et al. Investigation of endometrial abnormalities in asymptomatic women treated with tamoxifen and an evaluation of the role of endometrial screening. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2050–2054. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mourits MJ, Van der Zee AG, Willemse PH, et al. Discrepancy between ultrasonography and hysteroscopy and histology of endometrium in postmenopausal breast cancer patients using tamoxifen. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73:21–26. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tesoro MR, Borgida AF, MacLaurin NA, et al. Transvaginal endometrial sonography in postmenopausal women taking tamoxifen. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:363–366. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertelli G, Venturini M, Del Mastro L, et al. Tamoxifen and the endometrium: findings of pelvic ultrasound examination and endometrial biopsy in asymptomatic breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;47:41–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1005820115535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen I, Rosen DJ, Shapira J, et al. Endometrial changes with tamoxifen: comparison between tamoxifen-treated and nontreated asymptomatic, postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:185–190. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1994.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lahti E, Blanco G, Kauppila A, et al. Endometrial changes in postmenopausal breast cancer patients receiving tamoxifen. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:660–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Love CD, Dixon JM. Thickened endometrium caused by tamoxifen returns to normal following tamoxifen cessation. Breast. 2000;9:156–157. doi: 10.1054/brst.1999.0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menada MV, Papadia A, Lorenzi P, et al. Modification of ultrasonographically measured endometrial thickness after discontinuation of adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2004;25:321–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen I, Beyth Y, Azaria R, et al. Ultrasonographic measurement of endometrial changes following discontinuation of tamoxifen treatment in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. BJOG. 2000;107:1083–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bornstein J, Auslender R, Pascal B, et al. Diagnostic pitfalls of ultrasonographic uterine screening in women treated with tamoxifen. J Reprod Med. 1994;39:674–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG committee opinion. No. 336: tamoxifen and uterine cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1475–1478. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200606000-00057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Althuis MD, Sexton M, Langenberg P, et al. Surveillance for uterine abnormalities in tamoxifen-treated breast carcinoma survivors: a community based study. Cancer. 2000;89:800–810. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000815)89:4<800::aid-cncr12>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geisler J, King N, Anker G, et al. In vivo inhibition of aromatization by exemestane, a novel irreversible aromatase inhibitor, in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:2089–2093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geisler J, Haynes B, Anker G, et al. Influence of letrozole and anastrozole on total body aromatization and plasma estrogen levels in postmenopausal breast cancer patients evaluated in a randomised, cross-over-designed study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:751–757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) Trialists’ Group. Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 100-month analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coates AS, Keshaviah A, Thurlimann B, et al. Five years of letrozole compared with tamoxifen as initial adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer: update of study BIG 1-98. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:486–492. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coombes RC, Kilburn LS, Snowdon CF, et al. Survival and safety of exemestane versus tamoxifen after 2–3 years’ tamoxifen treatment (Intergroup Exemestane Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:559–570. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, et al. A randomised trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1081–1092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fallowfield LJ, Bliss JM, Porter LS, et al. Quality of life in the Intergroup Exemestane Study: a randomised trial of exemestane versus continued tamoxifen after 2 to 3 years of tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:910–917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coleman RE, Banks LM, Girgis SI, et al. Skeletal effects of exemestane on bone-mineral density, bone biomarkers, and fracture incidence in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer participating in the Intergroup Exemestane Study (IES): a randomised controlled study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:119–127. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerber B, Krause A, Reimer T, et al. Anastrozole versus tamoxifen treatment in postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive breast cancer and tamoxifen-induced endometrial pathology. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(4):1245–1250. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Markovitch O, Tepper R, Fishman A, et al. Aromatase inhibitors reverse tamoxifen induced endometrial ultrasonographic changes in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;101(2):185–190. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morales L, Timmerman D, Neven P, et al. Third generation aromatase inhibitors may prevent endometrial growth and reverse tamoxifen-induced uterine changes in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(1):70–74. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garuti G, Cellani F, Centinaio G, et al. Prospective endometrial assessment of breast cancer patients treated with third generation aromatase inhibitors. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103(2):599–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garrone O, Ortu S, Occelli M, et al. Reversal of tamoxifen induced endometrial modifications by switching to letrozole: a prospective transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) study in early breast cancer patients. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;22:69. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duffy S, Jackson TL, Lansdown M, et al. The ATAC (‘Arimidex’, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) adjuvant breast cancer trial: baseline endometrial sub-protocol data on the effectiveness of transvaginal ultrasonography and diagnostic hysteroscopy. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):70–74. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garuti G, Grossi F, Centinaio G, et al. Pretreatment and prospective assessment of endometrium in menopausal women taking tamoxifen for breast cancer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;132(1):101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]