Abstract

Background: Substantial numbers of cancer patients use complementary medicine therapies, even without a supportive evidence base. This study aimed to evaluate in a randomized controlled trial, the use of Medical Qigong (MQ) compared with usual care to improve the quality of life (QOL) of cancer patients.

Patients and methods: One hundred and sixty-two patients with a range of cancers were recruited. QOL and fatigue were measured by Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Fatigue, respectively, and mood status by Profile of Mood State. The inflammatory marker serum C-reactive protein (CRP) was monitored serially.

Results: Regression analysis indicated that the MQ group significantly improved overall QOL (t144 = −5.761, P < 0.001), fatigue (t153 = −5.621, P < 0.001), mood disturbance (t122 =2.346, P = 0.021) and inflammation (CRP) (t99 = 2.042, P < 0.044) compared with usual care after controlling for baseline variables.

Conclusions: This study indicates that MQ can improve cancer patients’ overall QOL and mood status and reduce specific side-effects of treatment. It may also produce physical benefits in the long term through reduced inflammation.

Keywords: cancer, fatigue, inflammation, mood, quality of life

introduction

Over the past 50 years, the prognosis associated with a diagnosis of cancer has markedly improved due to developments in multidisciplinary care [1]. Nonetheless, cancer is a profoundly stressful disease, posing both physical and psychological threats to the patient. The emotional distress of a diagnosis of cancer and the persistent side-effects of treatment significantly compromise patients’ quality of life (QOL) [2, 3].

A desire for more ‘holistic’ care [4] has led individuals diagnosed with cancer to seek out supportive and complementary medicine (CM) therapies to serve as adjuncts to standard medical care. For example, in Australia, 52% of cancer patients report having used CM [5], while in the United States, figures of up to 83% have been reported [6]. Despite the high rate of CM use in cancer patient populations, there is little available evidence from randomized trials to inform health professionals and patients in regard to the safety and efficacy of many CM therapies.

One CM therapy that is frequently used by cancer patients, but is yet to be thoroughly evaluated, is Medical Qigong (MQ). Qigong, a mind–body practice first developed over 5000 years ago, is an important part of traditional Chinese medicine [7]. MQ is a mind–body practice that uses physical activity and meditation to harmonize the body, mind and spirit. It is on the basis of the theory that discomfort, pain and sickness are a result of blockage or stagnation of energy flow in the energy channel in the human body. According to this theory, if there is a free flow and balance of energy, health can be improved and/or maintained and disease can be prevented [8]. Within western medicine, MQ can be understood within the mind–body medicine model, developed after the scientific discovery of the ‘relaxation response’ [9] and the development of the theory of psychoneuroimmunology [10]. Within this model, the efficacy of MQ is seen as having its source in an integrated hypothalamic response, resulting in homeostasis of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. This in turn causes reduced emotional and physical tension and improved immune function.

Several studies have indicated that MQ has many health benefits, such as decreased heart rate [11], decreased blood pressure [12], lowered lipid levels [13], decreased levels of circulating stress hormones [14] and enhanced immune function [15, 16]. Within the cancer literature, several uncontrolled studies have indicated that MQ may also have an impact on survival [8]. A review of the literature conducted by Chen et al. [8] indicated that MQ interventions can improve physical well-being (PWB) and psychological well-being in cancer populations and are cost effective because they can be run as group therapy. Unfortunately, most research evaluating Qigong has suffered from a lack of appropriate randomization and utilization of control groups. Studies have also tended to focus on limited numbers of biological and physical outcomes. To address this paucity of data in the literature, a small pilot study was conducted in 2007 to determine the effect of MQ on PWB and psychological well-being of cancer patients [17]. Using a randomized controlled design, we showed that MQ could improve the QOL of cancer patients; however, due to a small sample size more robust conclusions could not be drawn [17].

These encouraging preliminary data led us to conduct a larger randomized controlled trial of Qigong. The primary hypothesis of this study was that the MQ group would experience significant improvements in QOL compared with the control group. On the basis of the mind–body model, it was expected that the MQ group would also show greater reduction in fatigue and mood and decreased levels of inflammation by 10 weeks of follow-up. Inflammation was included as a marker of impact on the cancer itself. Several studies have indicated that chronic inflammation is associated with cancer incidence, progression and even survival [4–6].

patients and methods

The study population consisted of 162 adult patients diagnosed with cancer recruited from three large, university teaching hospitals. Patients who had a confirmed diagnosis of malignancy of any stage, were aged ≥18 years and had an expected survival length of >12 months were eligible for the trial. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a diagnosis of a major medical or psychiatric disorder (other than cancer), had a history of epilepsy, brain metastasis, delirium or dementia, had medical contraindications for exercise (e.g. significant orthopedic problem or cardiovascular disease) or were already practicing Qigong.

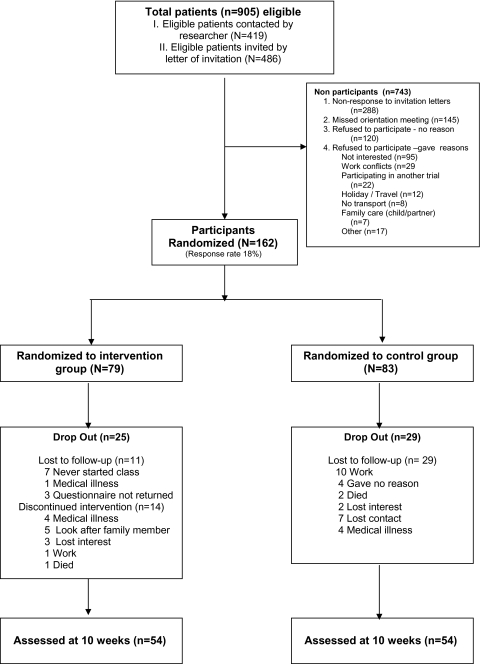

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through the trial. In the first phase of recruitment, from July 2006 to August 2007, trained recruiters approached cancer patients, whose oncologists identified them to be eligible, in the patient waiting room at the Medical Oncology Department of the participating hospitals. Eighty-one participants were recruited. In the second phase of recruitment from August 2007 to May 2008, those patients considered by their medical oncologist to be eligible received an invitation letter from their medical oncologist through the post. Another 81 participants were recruited. In both phases of recruitment, interested patients were invited to attend an information session about the study at which patients were further screened for exclusion criteria. After giving written consent, patients completed the baseline QOL measure and gave blood and were randomly assigned into the intervention and control groups. During the study, a total of nine MQ programs were offered at three hospitals. The number of participants in each group varied from 7 to 20 depending on the number recruited at each phase. Randomization, by computer, was stratified by treatment at baseline (currently undergoing or completed cancer treatment). Blinding the participants to the allocation was not possible due to the nature of intervention. The study received ethics approval from the University of Sydney and the participating hospitals.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of patients flow in this trial.

outcome measurement

QOL, fatigue, mood, and an inflammatory biomarker [C-reactive protein (CRP)] were measured at baseline preintervention and at 10 weeks postintervention. The primary outcome of QOL was measured with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General (FACT-G) [18]. This well-validated and widely used measure is a 27-item patient self-reported instrument designed to measure multidimensional QOL in ‘heterogeneous’ cancer patients. The FACT-G consists of four subscales assessing PWB, emotional well-being (EWB), social well-being (SWB), and functional well-being (FWB) with higher scores reflecting better QOL. Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) was assessed by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Fatigue (FACT-F) subscale. High scores on this 13-item scale reflect greater fatigue [19]. Mood was measured by the total score of the Profile of Mood State [20], which has six subscales with high scores reflecting more negative mood states. Inflammation was assessed by the serum CRP. This is recognized as a primary marker of inflammation and has been found in several studies to be an independent predictor of cancer prognosis [7, 8]. CRP measurement was determined in the Biochemistry Department of participating hospitals by particle-enhanced immunological agglutination using a Roche (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany)/Hitachi analyzer (Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

intervention

Patients assigned to the intervention group received usual medical care and were invited to attend an MQ (group therapy) program, held in the hospital where they were treated. The MQ program was run for 10 weeks with two supervised 90-min sessions per week. Participants were also encouraged to undertake home practice every day for at least half an hour.

The MQ intervention program was a modified traditional Qigong program, developed and delivered by the first author (BO), an experienced MQ instructor. The instructor is a Chinese medicine practitioner with >20 years experience of Qigong who trained in traditional Qigong in Korea, Daoist Qigong in China and Buddhist Qigong in Australia and has received clinical training in mind–body medicine at the Harvard Medical School. The program was modified from traditional Qigong practice by the instructor to specifically target the needs of cancer patients to control emotions and stress as well as to improve physical function. Each session consisted of 15-min discussion of health issues, 30-min gentle stretching and body movement in standing postures to stimulate the body along the energy channels, 15-min movement in seated posture (Dao Yin exercise for face, head, neck, shoulders, waist, lower back, legs, and feet), 30-min meditation including breathing exercises on the basis of energy channel theory in Chinese medicine, including natural breathing, chest breathing, abdominal breathing, breathing for energy regulation, and relaxation and feeling the Qi (nature’s/cosmic energy) and visualization.

To assess home practice, a diary was given to the participants to complete and return at the end of the 10-week program. Participants were advised to report or discuss any adverse effects with the MQ instructor, however none were reported.

Participants assigned to the control group received usual care and completed all outcome measures in the same time frame as the intervention group. Usual care comprised appropriate medical intervention, without the offer of additional CM. Participants were advised to undertake normal activities but were asked to refrain from joining an outside Qigong class. As the intervention was offered to these participants after the last outcome measurement, no patient joined an outside class.

statistical power and analyses

A total of 64 patients per arm were required to detect a clinically important difference [0.5 standard deviation (SD) effect size] between the intervention and control groups on the primary outcome measure of FACT-G, with 80% power, a type I error rate of 5% (two sided) and an (SD) of 15. To allow for dropouts (30%) and within-site clustering (intra-cluster correlation coefficient 0.03, design effect 1.10), 84 patients were required in each treatment group.

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS 15 and STATA 10.0. Descriptive statistics (frequency, mean, and SD) were used to describe and summarize baseline data. Chi-square tests and Mann–Whitney tests were carried out to investigate differences between the control and intervention groups, and completers and dropouts. To conduct an intention-to-treat analysis, missing data were dealt with by multiple imputations adjusted for gender, age, status of cancer treatment (completed anticancer treatment or undergoing anticancer treatment), week 0 baseline scores and intervention status. After multiple imputations, linear regression analyses were conducted to examine between-group differences in the outcome variables of QOL, fatigue, side-effects of treatment and symptoms, mood status and inflammation biomarker (CRP) at week 10 after controlling for the corresponding baseline variables.

results

A total of 162 adult patients participated in the study. Baseline characteristics (Table 1) were well balanced between intervention and control groups. The mean age of participants in this study was 60 years at baseline (SD = 12 years) ranging from 31 to 86 years. The most common primary cancer diagnosis among participants was breast cancer (34%) followed by colorectal cancer (12%). There were no significant differences in measurements of QOL, fatigue, mood status and inflammation biomarkers between intervention and control groups at baseline (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants at baseline

| Intervention (n = 79) | Control (n = 83) | Test statistic | df | P value | |

| Mean age (SD) | 60.1 (11.7) | 59.9 (11.3) | t = 0.210 | 159 | 0.834 |

| Gender, n (%) | χ2 = 0.314 | 1 | 0.575 | ||

| Female | 48 (60.8) | 45 (54.2) | |||

| Male | 31 (39.2) | 38 (45.8) | |||

| Martial status, n (%) | χ2 = 0.016 | 1 | 1.000 | ||

| Currently married or de facto relationship | 54 (70.1) | 54 (71.1) | |||

| Never married | 8 (10.4) | 7 (9.2) | |||

| Separated/divorced | 8 (10.4) | 11 (14.5) | |||

| Widowed | 7 (9.1) | 4 (5.3) | |||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | χ2 = 2.850 | 1 | 0.108 | ||

| Caucasian | 57 (77.0) | 49 (64.5) | |||

| Asian | 10 (13.5) | 17 (22.4) | |||

| Indigenous Australian | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.3) | |||

| Other | 6 (8.1) | 9 (11.8) | |||

| Educational level, n (%) | χ2 = 0.792 | 2 | 0.420 | ||

| Primary | 1 (1.3) | 7 (9.2) | |||

| Secondary | 35 (45.5) | 34 (44.7) | |||

| Undergraduate | 19 (24.7) | 19 (25.0) | |||

| Postgraduate | 22 (28.6) | 16 (21.1) | |||

| Primary cancer diagnosis, n (%) | χ2 = 0.702 | 1 | 0.473 | ||

| Breast cancer | 26 (37.7) | 21 (30.9) | |||

| Lung cancer | 6 (8.7) | 3 (4.4) | |||

| Prostate cancer | 6 (8.7) | 4 (5.9) | |||

| Colorectal cancer/bowel cancer | 8 (11.6) | 8 (11.8) | |||

| Other | 23 (33.3) | 32 (47.1) | |||

| Completion of cancer treatment, n (%) | χ2 = 0.030 | 1 | 0.861 | ||

| Completed | 40 (52.6) | 40 (54.1) | |||

| In progress | 36 (47.4) | 34 (45.9) |

n values vary due to missing data. n < 10 collapsed for χ2 test.

SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Baseline outcome measurement of participants

| Variables | Mean (SD) |

Test statistic | df | P value | |

| Intervention | Control | ||||

| QOL measured by FACT-Ga | |||||

| Physical well-being | 20.24 (5.48) | 20.63 (5.49) | −0.439 | 157 | 0.661 |

| Social well-being | 23.41 (6.47) | 23.63 (7.15) | −0.208 | 153 | 0.836 |

| Emotional well-being | 17.72 (4.13) | 17.21 (4.99) | 0.689 | 156 | 0.492 |

| Functional well-being | 17.42 (5.73) | 17.81 (6.06) | −0.420 | 157 | 0.675 |

| Total QOL | 78.93 (16.16) | 79.21 (18.21) | −0.103 | 150 | 0.918 |

| Fatigue measured by FACT-Fa | |||||

| Fatigue | 33.35 (11.45) | 33.09 (11.57) | 0.141 | 158 | 0.888 |

| Mood status measured by POMSb | |||||

| Tension and anxiety | 10.23 (7.02) | 11.20 (7.39) | −0.826 | 150 | 0.410 |

| Depression | 9.33 (9.99) | 12.32 (12.87) | −1.555 | 142 | 0.122 |

| Anger and hostility | 7.55 (6.92) | 10.07 (9.38) | −1.826 | 141 | 0.070 |

| Lack of vigour | 18.34 (6.87) | 16.55 (6.92) | 1.585 | 147 | 0.115 |

| Fatigue | 10.10 (6.66) | 10.15 (7.01) | −0.052 | 149 | 0.959 |

| Confusion | 7.75 (5.51) | 8.21 (5.93) | −0.494 | 151 | 0.622 |

| Total mood status | 62.85 (35.43) | 68.34 (41.75) | −0.813 | 129 | 0.418 |

| Inflammation | |||||

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 9.90 (23.78) | 12.25 (25.71) | −0.503 | 110 | 0.616 |

A higher score reflects a positive effect.

A lower score reflects a positive effect.

SD, standard deviation; QOL, quality of life; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General; FACT-F, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Fatigue; POMS, Profile of Mood State.

Dropout was relatively high but equivalent between the groups (32% in the intervention arm and 35% in the control). There were no significant differences between completers and dropouts on demographic or disease characteristics. Completers attended on average 8 of the 10 scheduled sessions. Only 50% of participants kept the home diary and returned it at the end of the program, making the calculation of home compliance difficult. Missing data were uncommon in outcome measures.

Within- and between-group changes in QOL, fatigue, mood and inflammation are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Effects of Medical Qigong (intention-to-treat analysis using multiply imputed data) within- and between-group differences

| Variables | Within group (week 10–week 0) |

Between groups (intervention and control) |

||||

| Mean difference from baseline (95% CI), independent samples t-test |

Mean difference between groups (95% CI), independent samples t-test | Regression statistics |

||||

| Medical Qigong group (n = 79) | Control group (n = 83) | t value | df | P values | ||

| QOL measured by FACT-Ga | ||||||

| Physical well-being | 3.06 (1.97 to 4.14) | 0.98 (0.04 to 1.91) | 2.08 (0.66 to 3.50) | −3.720 | 152 | <0.001 |

| Social well-being | 2.29 (1.25 to 3.32) | −0.97 (−2.00 to 0.06) | 3.26 (1.81 to 4.71) | −4.663 | 148 | <0.001 |

| Emotional well-being | 1.60 (0.86 to 2.35) | 0.05 (−0.75 to 0.85) | 1.55 (0.47 to 2.63) | −3.677 | 150 | <0.001 |

| Functional well-being | 2.46 (1.51 to 3.42) | −0.13 (−0.94 to 0.68) | 2.60 (1.35 to 3.84) | −4.467 | 151 | <0.001 |

| Total QOL | 8.86 (6.41 to 11.32) | −0.13 (−2.48 to 2.22) | 9.00 (5.62 to 12.36) | −5.761 | 144 | <0.001 |

| Fatigue measured by FACT-Fa | ||||||

| Fatigue | 6.34 (4.38 to 8.30) | 0.64 (−0.74 to 2.02) | 5.70 (3.32 to 8.09) | −5.621 | 153 | <0.001 |

| Mood status measured by POMSb | ||||||

| Tension and anxietyc | −1.71 (−2.94 to −0.48) | −0.47 (−1.84 to 0.90) | −1.24 (−3.06 to 0.58) | 2.239 | 136 | 0.027 |

| Depressionc | −1.01 (−2.62 to 0.59) | 1.54 (−0.52 to 3.61) | −2.56 (−5.14 to 0.01) | 2.215 | 108 | 0.029 |

| Anger and hostilityc | −0.05 (−1.30 to 1.21) | −0.30 (−1.83 to 1.24) | 0.25 (−1.71 to 2.20) | 1.359 | 104 | 0.177 |

| Lack of vigorc | −3.81 (−4.91 to −2.72) | 0.53 (−0.65 to 1.71) | −4.34 (−5.93 to −2.75) | 4.839 | 139 | <0.001 |

| Fatiguec | −2.42 (−3.79 to −1.05) | −1.30 (−2.63 to 0.03) | −1.12 (−3.01 to 0.77) | 2.632 | 126 | 0.010 |

| Confusionc | −0.76 (−1.68 to 1.17) | 0.11 (−0.90 to 1.12) | −0.87 (−2.23 to 0.49) | 1.929 | 137 | 0.056 |

| Total mood status | −8.73 (−14.62 to −2.84) | 1.91 (−5.25 to 9.07) | −10.64 (−19.81 to −1.47) | 2.346 | 122 | 0.021 |

| Inflammation biomarkerb | ||||||

| C-reactive protein (mg/l)c | −3.60 (−9.03 to 1.82) | 19.57 (5.37 to 33.76) | −23.17 (−37.08 to −9.26) | 2.042 | 99 | 0.044 |

Higher scores reflect positive effect of intervention.

Lower scores reflect positive effect of intervention.

Logarithmic transformations were used in the model.

CI, confidence interval; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General; QOL, quality of life; FACT-F, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Fatigue; POMS, Profile of Mood State.

Participants in the MQ group reported larger improvements in QOL than those in the usual care group at 10-week follow-up when controlling for baseline scores (t144 = −5.761, P < 0.001). QOL subdomain analyses also showed that changes in scores were significantly larger for all subdomains of QOL [PWB (t152 = −3.720, P < 0.001), SWB (t148 = −4.663, P < 0.001), EWB (t150 = −3.677, P < 0.001) and FWB (t151 = −4.467, P < 0.001)] in the intervention compared with the control group.

Participants in the MQ group had significantly larger improvements in scores on fatigue (t153 = −5.621, P < 0.001) measured by the FACT-F than those in the control group at 10 weeks. Participants in the MQ intervention had a greater reduction in mood disturbance than those in the control group overall (t122 = 2.346, P = 0.021) and on four subscales: tension and anxiety, depression, lack of vigor and fatigue. However, there were no differences between intervention and control groups on the remaining two subscales: anger and hostility, and confusion. Finally, participants in the MQ group had significant differences in the level of the inflammation biomarker (CRP) (t99 = 2.042, P = 0.044) than the control group at week 10.

discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the first randomized controlled trial with adequate statistical power which has been used to measure the impact of MQ in patients with cancer. The findings provide evidence for the impact of MQ on QOL, fatigue, mood status and inflammation in patients with cancer, major issues for cancer patients.

Our major findings were that scores on total QOL and all domains (PWB, SWB/family well-being, EWB and FWB) measured by the FACT-G were significantly improved in participants who completed the Qigong intervention at 10-week follow-up compared with the usual care control group. These results are consistent with the study of Tsang et al. [21] of MQ in elderly patients with chronic illness. It is sometimes the case that interventions may lead to improvements in outcomes that, while statistically significant, may not be clinically relevant and important. This does not appear to be the case in this study, where individuals in the MQ intervention scored an average of 8.23 points higher on the FACT-G measure of QOL than individuals in the usual care control group at 10-week follow-up. A 5- to 10-point difference on the FACT-G is considered to represent both a clinically and a socially important difference in QOL and functioning in cancer patients [22].

Another significant finding from this study was the positive effects of MQ on inflammation as measured by the CRP. While the precise mechanism through which MQ is able to decrease inflammation is unclear, one possible pathway is through MQ’s effect on the immune system. A number of studies have indicated that MQ leads to improved immune function [23, 24]. These findings indicate a need for further research on the impact of MQ on biological changes, such as immune function, cytokines and inflammation, in order to more fully understand these effects.

In this study, patients in the MQ intervention group experienced significantly less CRF than those in the usual care control group. A change of >3 points on the FACT-F measure of CRF is considered to represent a clinically important change in fatigue in a cancer population [25]; patients in the MQ intervention group reported a 6.34-point change in CRF as measured by that scale. Thus, the reduction in CRF reported was clinically as well as statistically significant. Results are consistent with other research which has found that MQ can lead to improvements in CRF [26] and to research that has linked mindfulness-based stress reduction [27], relaxation breathing exercises [26] and yoga [28] to reduction of CRF in a range of cancer populations. Physical exercise is also often recommended by cancer care professionals as a method of minimizing CRF and improving QOL. However, recent randomized controlled trials have reported that fatigue and QOL were not improved with physical exercise [29, 30]. The current study finding indicates that management of CRF and QOL may be more effective if improvements in psychological and emotional functioning are targeted as well as physical functioning, as in the case of the MQ intervention. More research may be necessary to clarify the relationship between CRF, QOL, MQ and physical exercise.

Moreover, participation in the MQ intervention led to better total mood status among cancer patients, specifically reduced tension, anxiety and depression and increased vigor. This is supported by previous research which found an effect of MQ on mood in elderly patients with chronic illness [21], although another study found no impact of Qigong on mood in patients with cancer [31]. There may be differences in the delivery of Qigong which account for these divergent results, emphasizing the need for very clear descriptions of intervention content in evaluation studies.

Finally, no adverse effects of MQ were reported by the cancer patients in this trial, which is reassuring. Safety of MQ practice for cancer patients is also supported by previous literature [32].

Although these results are positive and promising, there are some limitations to the study and methodological approach that should be taken into account when interpreting the results. First, inclusion of a control group receiving usual care means that the significant results may have been due to the additional attention received rather than the intervention. A usual care control group was chosen rather than a placebo sham group due to the early stage of this research. If a difference was detected between the groups, a subsequent larger study was planned to control for the effect of attention, and indeed this is now in the planning stage.

Secondly, contrary to recommendations for drug trials, neither the participants nor the instructors were blind to condition. Due to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to make use of a blinding protocol. As such, it is possible that the benefits reported from the MQ intervention were due to experimental bias and confounding factors (e.g. extra care versus non-extra care), participants’ expectancy (placebo effects) and social interactions. To reduce the likelihood that patients who knew they were in the intervention arm of the study would provide socially desirable responses, a third independent person distributed and collected the pre and post intervention questionnaires and carried out all data entry.

In this study, the completion rate was relatively low (76%) compared with other similar studies (85%) [30, 33]. Some studies that reported a low dropout rate (15%) recruited early-stage breast cancer patients [33], while studies that have reported a high dropout rate (35%) have recruited cancer patients with all stages of disease [34], similar to the current study. Dropout rate may be more dependent on the health status of participants than on other factors.

Participation in this study was voluntary and that may have created a potential selection bias, with those patients interested in Qigong participating and those with no interest in Qigong declining. This may limit the generalizability of the findings but does not invalidate the results for this sample.

Moreover, this study investigated the short-term benefits of the MQ intervention but not the longer term. It may be worthwhile to investigate whether the benefit is sustained in the long term with participants who continue to practice MQ at home.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study are positive and provide evidence that MQ is safe and effective in improving QOL, fatigue, mood status and reducing symptoms, side-effects and inflammation in cancer patients. Further studies examining long-term benefits of MQ, including a potential association between improvement in QOL and survival rate, may provide additional information that may assist patients with cancer and clinicians in providing optimal comprehensive cancer care.

funding

University of Sydney Cancer Research Fund. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the University of Sydney.

disclosure

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank support of study to the medical oncologists of Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Concord Hospital and Royal North Shore Hospital. The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of the biostatistician, Prof. Judy Simpson, who provided statistical assistance and especially to thank the participants who made this study possible.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2007. edition. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearman T. Quality of life and psychosocial adjustment in gynecologic cancer survivors. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:33. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trask P. Quality of life and emotional distress in advanced prostate cancer survivors undergoing chemotherapy. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:37. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan C, Ho PS, Chow E. A body-mind-spirit model in health: an Eastern approach. Soc Work Health Care. 2001;34:261–282. doi: 10.1300/j010v34n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller M, Boyer MJ, Butow PN, et al. The use of unproven methods of treatment by cancer patients. Frequency, expectations and cost. Support Care Cancer. 1998;6:337–347. doi: 10.1007/s005200050175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassileth BR, Deng G. Complementary and alternative therapies for cancer. Oncologist. 2004;9:80–89. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-1-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peiwen L. Management of Cancer with Chinese Medicine. St Alban, UK: Donica Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen K, Yeung R. Exploratory studies of Qigong therapy for cancer in China. Integr Cancer Ther. 2002;1:345–370. doi: 10.1177/1534735402238187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benson H, Klipper MZ. The Relaxation Response. London: Collins; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ader R, Felten DL, Cohen N. Psychoneuroimmunology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee MS, Rim YH, Jeong D-M, et al. Nonlinear analysis of heart rate variability during Qi therapy (external Qigong) Am J Chin Med. 2005;33:579–588. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X05003181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee M-S, Lee MS, Kim H-J, Moon S-R. Qigong reduced blood pressure and catecholamine levels of patients with essential hypertension. Int J Neurosci. 2003;113:1691–1701. doi: 10.1080/00207450390245306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee MS, Kim HJ, Choi ES. Effects of qigong on blood pressure, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and other lipid levels in essential hypertension patients. Int J Neurosci. 2004;114:777–786. doi: 10.1080/00207450490441028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryu H, Lee HS, Shin YS, et al. Acute effect of qigong training on stress hormonal levels in man. Am J Chin Med. 1996;24:193–198. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X96000256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manzaneque JM, Vera FM, Maldonado EF, et al. Assessment of immunological parameters following a qigong training program. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:CR264–CR2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryu H, Jun CD, Lee BS, et al. Effect of qigong training on proportions of T lymphocyte subsets in human peripheral blood. Am J Chin Med. 1995;23:27–36. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X95000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh B, Butow P, Mullan B, Clarke S. Medical Qigong for cancer patients: pilot study of impact on quality of life, side effects of treatment and inflammation. Am J Chin Med. 2008;36:459–472. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X08005904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, et al. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNair D, Loor M, Droppleman L. Profile of Mood Status (Revised) San Diego, CA: EdITS/Educational and Industrial Testing Services; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsang HWH, Fung KMT, Chan ASM, et al. Effect of a qigong exercise programme on elderly with depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:890–897. doi: 10.1002/gps.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:139–144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeh M, Lee T, Chen H, Chao T. The influences of Chan-Chuang qi-gong therapy on complete blood cell counts in breast cancer patients treated with chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29:149–155. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200603000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo S, Tong T. First World Conference for Academic Exchange of Medical Qigong. edition. Beijing, China: 1988. Effect of vital gate qigong exercise on malignant Tumor. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cella D, Eton DT, Lai JS, et al. Combining anchor and distribution-based methods to derive minimal clinically important differences on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) anemia and fatigue scales. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:547–561. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00529-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim S-D, Kim H-S. Effects of a relaxation breathing exercise on fatigue in haemopoietic stem cell transplantation patients. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:51–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlson LE, Garland SN. Impact of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on sleep, mood, stress and fatigue symptoms in cancer outpatients. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12:278–285. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1204_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danhauer S, Tooze J, Farmer D, et al. Restorative yoga for women with ovarian or breast cancer: findings from a pilot study. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2008;6:47–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Mackey JR, et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4396–4404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mutrie N, Campbell AM, Whyte F, et al. Benefits of supervised group exercise programme for women being treated for early stage breast cancer: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;334:517. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39094.648553.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee T-I, Chen H-H, Yeh M-L. Effects of chan-chuang qigong on improving symptom and psychological distress in chemotherapy patients. Am J Chin Med. 2006;34:37–46. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X06003618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lam W-Y. Masters Thesis. Hong Kong University; 2004. A randomised, controlled trial of Guolin qigong in patients receiving transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Speca M, Carlson LE, Goodey E, Angen M. A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: the effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:613–622. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raghavendra RM, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR, et al. Effects of an integrated yoga programme on chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis in breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care. 2007;16:462–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]