Abstract

Cresols, monomethyl derivatives of phenol, are high production chemicals with potential for human exposure. The three isomeric forms of cresol are used individually or in mixtures as disinfectants, preservatives, and solvents or as intermediates in the production of antioxidants, fragrances, herbicides, insecticides, dyes, and explosives. Carcinogenesis studies were conducted in groups of 50 male F344/N rats and 50 female B6C3F1 mice exposed to a 60:40 mixture of m and p cresols (m-/p-cresol) in feed. Rats and mice were fed diets containing 0, 1500, 5000, or 15,000 ppm and 0, 1000, 3000, or 10,000 ppm, respectively. Survival of each exposed group was similar to that of their respective control group. Mean body weight gains were depressed in rats exposed to 15,000 ppm and in mice exposed to 3000 ppm and higher. A decrease of 25% over that of controls for the final mean body weight in mice exposed to 10,000 ppm appeared to be associated with lack of palatability of the feed. A marginally increased incidence of renal tubule adenoma was observed in the 15,000 ppm-exposed rats. The increased incidence was not statistically significant, but did exceed the range of historical controls. No increased incidence of hyperplasia of the renal tubules was observed; however, a significantly increased incidence of hyperplasia of the transitional epithelium associated with an increased incidence of nephropathy was observed at the high exposure concentration. The only significantly increased incidence of a neoplastic lesion related to cresol exposure observed in these studies was that of squamous cell papilloma in the forestomach of 10,000 ppm-exposed mice. A definitive association with irritation at the site-of-contact could not be made because of limited evidence of injury to the gastric mucosa at the time of necropsy. However, given the minimal chemical-related neoplastic response in these studies, it was concluded that there was no clear evidence of carcinogenicity in male rats or female mice exposed to the cresol mixture.

Keywords: carcinogenicity, cresols, m-cresol, p-cresol, forestomach papilloma, renal tubule adenoma

1. Introduction

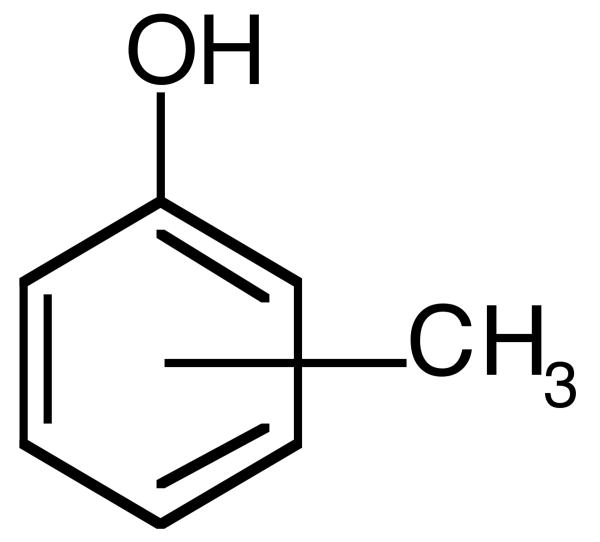

Cresols, monomethyl derivatives of phenol, exist as three isomers (ortho, meta, and para or o, m, and p; see Figure 1 for general structure) and are produced commercially by chemical synthesis or by distillation from petroleum or coal tar (Kirk-Othmer, 2004). Volumes of U.S. production and import are in the 100's of millions of lbs/year (ATSDR, 2006). Cresol isomers are used individually or in mixtures in the production of disinfectants, preservatives, dyes, fragrances, herbicides, insecticides, explosives, and as antioxidants used to stabilize lubricating oil, motor fuels, rubber, polymers, elastomers, and food. Mixtures of cresols are used in wood preservatives and in solvents for synthetic resin coatings, degreasing agents, ore flotation, paints, and textile products. Cresols occur naturally in oils of some plants and are formed during combustion of cigarettes, petroleum-based fuels, coal, wood, and other natural materials (IPCS, 1995). Various foods and beverages contain cresols (Lehtonen, 1982; Ho et al. 1983; Suriyaphan et al., 2001; Kilic and Lindsay, 2005; Guillén et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2002) and cresols have been detected in air, sediment, soil, surface and groundwater, primarily near point sources (McKnight et al., 1982; Bezacinsky et al. 1984; Jay and Stieglitz, 1995; Nielsen et al., 1995; Jin et al., 1999; Schwarzbauer et al., 2000; Thornton et al., 2001; Atagana et al., 2003; Tortajada-Genaro et al., 2003).

Figure 1.

Structure of cresols

High production and wide distribution of cresols in the environment indicate the potential for widespread exposure to humans. However, levels of exposure certainly vary among individuals depending on their occupation, lifestyle, and location. The USEPA has reported an estimated ambient concentration of cresol in the atmosphere of ca. 32 ng/m3 and concentrations have been detected in contaminated soil and groundwater as high as 55 mg/kg and 16 mg/L, respectively (ATSDR, 2006).

In humans, cresols or their metabolites are detected in tissues and urine following inhalation, dermal, or accidental and intentional oral exposure (Green, 1975; Yashiki et al., 1990; Wu et al., 1998; IPCS, 1995). Cresols are also detected in humans following absorption of other phenolic chemicals, e.g. toluene (Woiwode et al., 1981; Dills et al., 1997; Pierce et al., 2002). p-Cresol forms endogenously from metabolism of tyrosine by gut microflora (Bone et al., 1976). In rats, m and p cresols administered by gavage were absorbed, detected in blood, and distributed to major tissues such as brain, kidney, liver, lung, muscle, and spleen (Morinaga et al, 2004). Cresols primarily are conjugated to glucuronic acid or undergo sulfation and are excreted in urine of rabbits, rats, and humans (Williams, 1938; Bray et al., 1950; Ogata et al., 1995; Lesaffer et al., 2003; Morinaga et al., 2004). p-Cresol may be metabolized through reactive pathways as indicated by detection of p-hydroxybenzoic acid in the urine of p-cresol-dosed rabbits (Bray et al., 1950) and p-cresol-derived glutathione conjugates in rat or human microsomal preparations (Thompson et al., 1995; Yan et al., 2005).

Cresols are known respiratory irritants in animals and humans (ATSDR, 2006). Further, Vernot et al. (1977) determined that technical grade cresol (and individual isomers) were corrosive to the skin of rabbits. Burns and fatalities have been recorded in humans accidentally or intentionally exposed to cresol-containing products (Green, 1975; Yashiki et al., 1990; Monma-Ohtaki et al., 2002, ATSDR, 2006). Oral LD50's ranged from 344-828 mg/kg in mice and 1350-2020 mg/kg in rats receiving the isomers as 10% solutions, to 121-207 mg/kg for neat solutions administered to rats (IPCS, 1995). In 28-day toxicity studies conducted by the NTP (1992) male and female F344/N rats and B6C3F1 mice (n=5/group) were fed diets containing up to 30,000 ppm of either individual cresols or a mixture consisting of 60:40 m- and p- cresols (m-/p-cresol). All rats survived, but some mice, including all receiving the highest concentration of p-cresol, died or were moribund before the end of the study. Clinical signs of toxicity, typically consisting of hunched posture, thin appearance, and rough hair coat were observed only at the higher exposure concentrations and were more prevalent in mice. The major histopathological effect of cresol exposure was hyperplasia in the nasal cavities, specific to male and female rats and mice receiving either p- or m-/p-cresol. Hyperplasia of the esophagus and forestomach was observed in some male and female rats and one male mouse exposed to m-/p-cresol. In 13-week studies, survival was near 100% for groups of rats (n=20/group) receiving concentrations up to 30,000 ppm of either o-cresol or m-/p-cresol and mice (n=10/group) receiving up to 20,000 ppm or 10,000 ppm, of o-cresol or m-/p-cresol, respectively (NTP, 1992). Clinical signs of toxicity were minimal and all groups gained weight. Increased incidence of hyperplasia of the respiratory epithelium was observed in male and female rats and male mice exposed to m-/p-cresol. Hyperplasia of the forestomach was observed at increased incidence only in male and female mice exposed to o-cresol.

The carcinogenic potential of cresols has not been adequately evaluated. However, results of two separate studies indicate that cresols are tumor promoters in rodents. An increased incidence of skin papillomas was observed in mice receiving any of the three cresol isomers by dermal administration twice weekly for 12 weeks, following an initial application of the tumor initiator dimethyl benzanthracene (Boutwell and Bosch, 1959). Yanysheva et al. (1993) observed an increased incidence of forestomach papillomas and carcinomas in mice associated with repeated oral administration (over 30 weeks) of o-cresol with benzo[a]pyrene. m-/p-Cresol was negative for genotoxicity in various strains of Salmonella typhimurium with or without hamster or rat S9 (NTP, 1992). Exposure to o-cresol and m-/p-cresol did not increase the frequencies of micronucleated erthrocytes in male or female mice in the 13-week studies conducted by the NTP (1992).

In the present studies the carcinogenic potential of cresol was investigated in male F344/N rats and female B6C3F1 mice. The 60:40 mixture of m and p cresols, used in the NTP (1992) 13-week studies, was chosen as the test chemical. The mixture represented the ratio of the two isomers distilled from coke-oven tars in the U.S. (Kirk-Othmer, 1997) and was chosen over o-cresol due to the broader spectrum of histopathological effects associated with m-/p-cresol in the 13-week studies (NTP, 1992). An oral route of exposure was chosen for cresols in the prechronic and present studies to mimic potential long-term exposure of humans to cresols in contaminated groundwater. However, the cresols were administered in feed, rather than drinking water, due to solubility and palatability problems of the higher exposure concentrations in water. The non-traditional carcinogenesis study protocol omitting female rats and male mice from the present studies was based on a retrospective analysis of several hundred National Cancer Institute and NTP carcinogenicity bioassays (Huff et al., 1991). In those studies, 91% of 161 chemicals with positive responses were identified in male rats and/or female mice. It is generally accepted that the possibility of observing a positive carcinogenic response only in female rats and/or male mice (9% in the previous studies) would preclude omitting these groups from a 2-year bioassay. However, phenol and toluene are structurally similar to cresols and both of these well-studied chemicals have been found to be negative for carcinogenicity in traditional NTP 2-year bioassays (using male and female rats and mice) (NTP, 1980, NTP, 1990). Therefore, the probability of observing a carcinogenic response specific to cresol-exposed female rats and/or male mice was considered to be negligible. The omission of these groups from the present studies reduced the number of animals needed to conduct these studies and provided an opportunity to evaluate the modified protocol for use in carcinogenicity testing of specific chemicals.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemical

A mixture of 60:40 m- and p-cresols (m-/p-cresol; CAS # 1319-77-3) was obtained from Merichem Company (Houston, TX). The identity and purity (> 99.5%) of the chemical was determined using infared spectrometry, GC/MS, and NMR. Periodic GC analysis of the bulk chemical indicated no degradation over the course of the 2-year studies. The dose formulations were prepared monthly by mixing m-/p-cresol with NTP-2000 feed (Zeigler Brothers, Gardners, PA). The prepared dosed-feed was stored in plastic bags in the dark at 25° C or less for up to 42 days. All stored dose formulations were periodically analyzed using GC and all were found to be within 10% of their target concentrations. Stability of the chemical in feed was confirmed for the maximum time in storage and for at least 4 days under simulated animal room conditions.

2.2. Experimental animals and housing conditions

All rodent studies were conducted by Battelle Columbus Laboratories (Columbus, OH) in facilities accredited by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC, Rockville, MD) and in accordance with the United States Public Health Service policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the National Academies of Sciences Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the Battelle Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male F344/N rats and female B6C3F1 mice were obtained from Taconic Laboratory Animals and Services (Germantown, NY). Animals were quarantined (11 and 12 days for rats and mice respectively) in environmentally controlled rooms for exposure to the dosed feed at approximately 6 weeks old. The environment consisted of a temperature of 22 ± 2° C, relative humidity of 50 ± 15%, and a 12-h light/dark cycle. Rats were housed 2-3/cage and mice were housed 5/cage. Male mice from the same source were included in the study rooms with the female mice to ensure normal estrous cycling. Feed (NTP-2000 w/wo m-/p-cresol) and water were provided for ad libitum consumption.

2.3. Experimental design

Groups of 50 male F344/N rats were fed diets containing 0, 1500, 5000, or 15000 ppm for 105 weeks. Groups of 50 female mice were fed diets containing 0, 1000, 3000, or 10000 ppm for 106-107 weeks. The highest exposure concentrations were chosen based on observations of minimal toxicity at these levels in previous 13-week studies of cresols (NTP 1992). During the 2-year studies, animals were observed twice daily for signs of moribundity and mortality. Body weights were recorded initially, weekly for the first 13 weeks, 4-week intervals afterwards, and at termination. Clinical observations were recorded during week five, 4-week intervals afterwards, and at the end of the studies. Following CO2 asphyxiation, necropsies were performed and organs and tissues were examined for grossly visible lesions. All major tissues, including each of the paired organs (e.g. kidney) were fixed and preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin, processed and trimmed, embedded in paraffin, sectioned to a thickness of 4 to 6 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for microscopic examination. In the rat, an extended evaluation of renal lesions was performed by obtaining 3-4 additional sections from both kidneys, embedding the tissues in separate paraffin blocks, and step sectioning them at 1 mm intervals. All histopathological evaluations were performed by a veterinary pathologist and reviewed by quality assessment pathologists and the members of the NTP Pathology Working Group.

2.4. Statistical methods

The probability of survival was estimated by the product-limit procedure of Kaplan and Meier (1958). Dose-related effects on survival were determined using a method described by Cox (1972) and Tarone's (1975) life table test. The Poly-k test (Bailer and Portier, 1988; Portier and Bailer, 1989; Piegorsch and Bailer, 1997) was used to assess the prevalence of neoplasm and nonneoplastic lesions.

3. Results

3.1 Male F344/N rats

No significant differences in survival were observed between the control and cresol-exposed groups, with approximately 65% of the animals surviving to study termination (range = 62-68%). The mean body weights of rats receiving 1500 and 5000 ppm did not significantly differ from controls over time; however, the mean body weight of rats exposed to 15,000 ppm cresols was only 85% that of controls by the end of the study (420 vs. 495 g). The difference in mean weight gain was apparent within one week of study initiation (129 vs. 139 g) and remained lower throughout the rest of the study. In contrast, feed consumption in the 15,000 ppm group was lower than controls in the first week (11.3 g/day vs. 15.4 g/day) but recovered to near control levels by week 2 (15.4 g/day vs. 16.0 g/day). Survival and growth curves as well as feed consumption data for rats and mice (described below) can be assessed at http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ (see report #TR550 and accompanying data). Average daily doses for the three cresol-exposed groups were calculated as 70, 230, and 720 mg/kg. No overt signs of toxicity attributable to cresol exposure were observed in any of these groups.

The kidney was a target for cresol-related effects in the male F344/N rat. An increased incidence of renal tubule adenoma was observed in rats exposed to 15,000 ppm (Table 1). The increased incidence of the lesion, detected in 3 of 50 animals (6%) following the standard evaluation of kidney sections, was not significant, but did exceed the historical incidence (0-2%) for renal tubule adenoma in control male rats of feed studies. An examination of additional sections of the kidneys of the 15,000 ppm group resulted in detection of a renal tubule adenoma in one additional animal. This finding resulted in a p value just outside the range of statistical significance for increased incidence of this benign tumor in the kidney of male F344/N rats. No increased incidence of renal tubule hyperplasia was observed in these rats. However, a significant increase in hyperplasia of the transitional epithelium and a slight increase in severity of nephropathy were observed in rats exposed to 15,000 ppm.

Table 1.

Incidences of neoplasms and nonneoplastic lesions of the kidney in male F344/N rats

| Exposure concentration (ppm) | 0 | 1500 | 5000 | 15,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number examined | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Single sections (Standard evaluation) | ||||

| Renal tubule, hyperplasia | 2a (1.0) b | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.0) |

| Renal tubule, adenoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3c |

| Pelvis, transitional epithelium, hyperplasia | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 8* (1.9) |

| Nephropathy | 47 (1.4) | 48 (1.4) | 46 (1.7) | 49 (2.1) |

| Step sections (Extended evaluation) | ||||

| Renal tubule, hyperplasia | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Renal tubule, adenoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Single and step sections (combined) | ||||

| Renal tubule, hyperplasia | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Renal tubule, adenoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4d |

Animals with lesions.

Average severity of lesions: 1 = minimal, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = marked.

p = 0.109; Exceeds the range of historical controls (0-2%).

Not significantly different (p = 0.054) from controls.

Significantly different (p ≤ 0.01) from the control group.

The nose was a major site for cresol-related nonneoplastic changes in the male F344/N rat (Table 2). Inflammation, hyperplasia of goblet cells, and hyperplasia and metaplasia of the respiratory epithelium were detected at significantly increased incidence in the nasal cavity. These lesions occurred primarily in Level I of the three levels of the nasal cavity routinely examined in NTP toxicity and carcinogenicity studies. Level I is excised just posterior to the upper incisors and contains naso- and maxilloturbinates lined by ciliated respiratory type epithelium (Uraih and Maronpot, 1990).

Table 2.

Incidences of nonneoplastic lesions in male F344/N rats

| Exposure concentration (ppm) | 0 | 1500 | 5000 | 15,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number examined | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Nose, | ||||

| Inflammation | 17a (1.5)b | 19 (1.6) | 19 (1.3) | 28* (1.4) |

| Goblet cell, hyperplasia | 23 (1.1) | 40** (1.1) | 42** (1.2) | 47** (1.6) |

| Respiratory epithelium, hyperplasia | 3 (1.0) | 17** (1.0) | 31**(1.0) | 47**(1.2) |

| Respiratory epithelium, metaplasia | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 8** (1.0) | 40** (1.5) |

| Liver, eosinophilic focus | 14 | 14 | 13 | 23* |

Animals with lesions.

Average severity of lesions: 1 = minimal, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = marked.

Significantly different (p ≤ 0.05) from controls.

Significantly different (p ≤ 0.01) from controls.

No increased incidences of neoplastic or nonneoplastic lesions were observed in other tissues, with the exception of liver. The incidence of eosinophilic focus, was significantly increased in the 15,000 ppm group (Table 2).

3.2. Female B6C3F1 mice

As in male rats, no significant differences in survival between control and cresol-exposed mice were observed. Survival at the terminal timepoint ranged from a low of 82% in controls to a high of 90% in the 3000 ppm mice. In contrast to rats, cresol affected mean body weights in two groups. Both the 3000 and 10,000 ppm groups weighed significantly less than controls at sacrifice. Mean body weights of the two groups were similar to controls in the initial months of the study, e.g. the range = 25-28 g at day 85, but declined relative to controls afterwards (data not shown). The final mean body weights were 52 g, 51 g, 46 g, and 39 g for the control, 1000, 3000, and 10,000 ppm groups, respectively. Overall, the 10,000 ppm group consumed 13% less feed than controls in the study (data not shown). Feed consumption in the 1000 and 3000 ppm groups was similar to that of controls. Calculated daily doses to the three cresol-exposed groups of mice (100, 300, and 1040 mg/kg) were higher than those for rats. As in male rats, no overt signs of toxicity were observed in cresol-exposed female mice.

The forestomach was a primary site for cresol-related effects in the female B6C3F1 mouse (Table 3). Squamous cell papilloma was observed in one animal each in the 1000 and 3000 ppm groups and occurred at a significantly increased incidence (10 of 50) in the 10,000 ppm group. Hyperplasia of the forestomach epihelium was observed in two mice of the high-dose group, but the increased incidence was not significant and the severity of these lesions was considered to be minimal to mild. Neither hyperplasia, nor other histopathological effects were observed in the forestomach of the other groups.

Table 3.

Neoplastic and nonneoplastic lesions of the forestomach in female B6C3F1 mice

| Exposure concentration (ppm) | 0 | 1000 | 3000 | 10,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number examined | 50 | 50 | 49 | 50 |

| Epithelium, hyperplasia | 0a | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.5)b |

| Squamous cell papilloma | 0 | 1 | 1 | 10* |

Animals with lesions.

Average severity of lesions: 1 = minimal, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = marked.

Significantly different (p < 0.001) from controls.

The other major sites for cresol-related effects in the female B6C3F1 mouse were in the respiratory system (Table 4). As in the male rat, a dose-related increase in hyperplasia of the epithelium of the nasal cavity was detected. This lesion was significantly increased in the 3000 and 10,000 ppm groups. Squamous metaplasia in the respiratory epithelium occurred in two mice exposed to 10,000 ppm, but the increase was not significant. These lesions were primarily detected in Level I of the nasal cavity as described above. In the lung, hyperplasia of the bronchiole was observed in a majority of the mice exposed to m-/p-cresol. The lesion was not detected in any of the control mice, but increased in frequency and severity (from minimal to moderate) with increasing exposure concentration. Although not significant, hyperplasia of the alveolar epithelium was observed in three mice exposed to 10,000 ppm.

Table 4.

Incidences of nonneoplastic lesions in female B6C3F1 mice

| Exposure concentration (ppm) | 0 | 1000 | 3000 | 10,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number examined | 50 | 50 | 49 | 50 |

| Nose, | ||||

| Respiratory epithelium, hyperplasia | 0a | 0 | 28* (1.3)b | 45* (2.2) |

| Respiratory epithelium, metaplasia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.0) |

| Lung, | ||||

| Bronchiole, hyperplasia | 0 | 42* (1.0) | 44* (2.0) | 47* (3.0) |

| Alveolar epithelium, hyperplasia | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 3 (2.7) |

| Thyroid gland, follicle, degeneration | 7 (2.0) | 24* (1.8) | 24* (1.8) | 21* (1.8) |

| Liver, eosinophilic focus | 1 | 0 | 2 | 12* |

Animals with lesions.

Average severity of lesions: 1 = minimal, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = marked.

Significantly different (p ≤ 0.1) from controls.

There were increased incidences of follicular degeneration of the thyroid gland and eosinophilic focus of the liver in cresol-exposed mice (Table 4). The incidence of the thyroid lesion was increased relative to controls in all cresol-exposed groups. The severity of follicular degeneration was considered to be mild and did not increase with increased exposure concentration. The liver lesion was observed at increased incidence only in the 10,000 ppm group. Increased incidences of neoplastic or non-neoplastic lesions were not detected in any other tissues examined in cresol-exposed mice.

4. Discussion

The present 2-year studies were conducted by the NTP to evaluate and characterize the potential carcinogenicity of cresols in rats and mice. The need was based on the lack of chronic toxicity data and the potential for human exposure to cresols.

No differences in survival of cresol-exposed rats or mice relative to controls were observed in these studies, nor were any clinical findings related to cresol exposure observed in either species. However, the final mean body weights of some cresol-exposed groups were less than controls. The 15,000 ppm rats consumed significantly less feed than the controls in the first week of cresol exposure; presumably due to lack of palatability of the feed. However, rats seemed to develop a tolerance to the high exposure concentration as evidenced by the rebound of feed consumption to near that of controls by the second week of the study. Mice appeared to be more sensitive than rats to cresols in feed. The 10,000 ppm mice weighed 25% less than controls at the end of the study; a result that would not have been predicted from the data obtained from similarly dosed mice in the NTP 13-week study (NTP 1992). The severe reduction in weight gain in this group correlated with a significant drop in feed consumption over the course of the study. As in rats, these results are attributed to lack of palatability of the feed containing high amounts of cresols. Cresols are known respiratory irritants in humans and animals (ATSDR 2006) and the high exposure concentration may have been irritating to respiratory, and other biological membranes. The apparent greater sensitivity of the 10,000 ppm mice over that of the 15,000 ppm rats may be explained by the greater relative dose, 1040 mg/kg/day to the mice, compared to 720 mg/kg/day to the rats. It is unlikely that the female mice would have consumed greater amounts of cresols in feed; therefore, 10,000 ppm probably was at, or near the maximum dose that could be tolerated by this route of administration.

Exposure concentration-related effects in the nose of both rats and mice and the lung of mice indicated that cresols were irritating to these tissues. Increased incidences of goblet cell hyperplasia, inflammation, squamous cell metaplasia, and respiratory epithelium hyperplasia were observed in rats. Respiratory epithelium hyperplasia and hyperplasia of the bronchioles were observed at increased incidences in cresol-exposed mice. Such lesions are considered to be an adaptive response and are among those commonly observed in NTP inhalation studies of chemicals known to be irritants (NTP, 2000). It is possible that the nonneoplastic lesions observed in the present studies are due to inhalation exposure of the cresols, specifically p-cresol, volatilizing from the feed during consumption, and not from systemic exposure following oral absorption. Cresols are volatile, as directly demonstrated by their recovery in the headspace of sample vials following acid hydrolysis of human urine at room temperature (Fustinoli et al., 2005). Further, the results of the 28-day studies conducted by the NTP (NTP, 1992) suggest that exposure to p-cresol, not m-cresol resulted in nasal irritation in the present study. It may be that p-cresol is the most irritating of the three isomers or it could be speculated that the increased toxicity of p-cresol to the respiratory tract was metabolism-dependent. A minor pathway of p-cresol metabolism observed in rabbits was oxidation to p-hydroxybenzoic acid through p-hydroxybenzaldehyde (Bray et al., 1950). However, no hydroxybenzoic acids were detected following administration of either o- or m-cresol in the study. The complement of enzymes necessary for biotransformation of p-cresol to an aldehyde are present in the rodent nasal mucosa (Bogdanffy, 1990) and it could be assumed that p-hydroxybenzaldehyde is a more potent irritant than the parent cresol. Aldehydes such as acetaldehyde and formaldehyde are well-known irritants of the respiratory system of humans and animals following inhalation exposure (ATSDR, 1999; USEPA, 1994).

The only cresol-related neoplastic effect observed in rats in the present study was a minimal increase in renal tubule adenoma following exposure to 15,000 ppm. The lesions were small and unremarkable and the increased incidence was not statistically significant. Further, no cresol-related hyperplasia of the renal tubule was detected in these rats. Most rats, including controls, exhibited chronic progressive nephropathy, a common spontaneous lesion in the aging F344/N rat (Seely et al., 2002). The significantly increased incidence of hyperplasia of the transitional epithelium in the 15,000 ppm rats was thought to be secondary to the slight increase in the severity of nephropathy in these animals over that of controls. Increased severity of nephropathy has been associated with marginal increases in renal tubule cell neoplasms in previous NTP studies and the slight increase in incidence of adenomas observed here may correlate with the effect (Seely et al., 2002). Alternatively, m-/p-cresol potentially could damage renal tubule cells by a mechanism similar to that proposed for hydroquinone (HQ) (Lau et al., 2001). HQ is nongenotoxic, but markedly increases the number of tubular cell adenomas when administered to F344/N male rats at nephrotoxic doses. The authors attributed the effect to a minor metabolite, 2,3,5-tris(glutathione-S-yl) HQ, a potent toxic and redox-active species. The formation of benzoquinones from m- and p-cresol and quinone methide from p-cresol is inferred from identification of specific glutathione conjugates formed in microsomal incubations (Thompson et al., 1995; Yan et al., 2005). However, the formation of potentially reactive quinone-like metabolite(s) in rats exposed to high doses of cresol should be negligible compared to that following administration of nephrotoxic doses of HQ to rats.

In the current 2–year studies, an increased incidence of squamous cell papilloma was observed in the forestomach of mice exposed to m-/p-cresol. Many mutagenic chemicals produce tumors in the forestomach and exposure to some nongenotoxic chemicals is associated with tumorigenesis in this tissue (Harrison, 1992). For instance, butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) is considered to be nongenotoxic, but produces a low incidence of carcinoma in the forestomach of rodents (Ito et al., 1983). Evidence indicates that cresols, including the m-/p-cresol mixture have little or no genotoxic potential (NTP, 1992; IPCS, 1995; ATSDR, 2006). Repeated exposure to nongenotoxic irritants can damage squamous epithelium leading to regeneration involving atypical cellular proliferation capable of progressing to benign and malignant tumors (Harrison 1992). In the present study, the etiology of the papillomas could not be adequately correlated to the mechanism of chemical irritation, given the limited evidence of injury to the gastric mucosa in these animals. However, regenerative changes apparently due to irritation were observed in the esophagus and forestomach of some cresol-exposed animals in the subchronic studies conducted by the NTP (1992). Therefore, it is plausible that the papillomas observed in the present study were associated with regenerative changes that were resolved over time. No other neoplasms associated with cresol exposure were observed in this, or any other tissue in female mice.

In conclusion, under the conditions of these studies, no clear evidence of carcinogenicity was observed in rats or mice exposed to a 60:40 mixture of m- and p-cresols in feed. The tumorigenic response in male rats was not significant and evidence of tumorigenic activity was observed in female mice only at a site-of-contact. The nontraditional study design (omission of female rats and male mice) used here appeared to be adequate for detecting neoplastic responses in rodents exposed to cresols. In these studies, neoplasms, all benign, were detected at increased incidence at only one target site in either male rats or female mice and it is unlikely, given the chemical characteristics and biological fate of cresols, that hormonal differences would result in an appreciable difference in neoplastic response in the female rat or male mouse.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. The authors thank Drs. June Dunnick and Michelle Hooth of the NTP for their critical review of the manuscript.

References

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Toxicological Profile for Formaldehyde. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Draft Toxicological Profile for Cresols. 2006 http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp34.pdf. [PubMed]

- Atagana HI, Haynes RJ, Wallis FM. Optimization of soil physical and chemical conditions for the bioremediation of creosote-contaminated soil. Biodegradation. 2003;14:297–307. doi: 10.1023/a:1024730722751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailer AJ, Portier CJ. Effects of treatment-induced mortality and tumor-induced mortality on tests for carcinogenicity in small samples. Biometrics. 1988;44:417–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezacinsky M, Pilatova B, Jirele V, Bencko V. To the problem of trace elements and hydrocarbons emissions from combustion of coal. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1984;28:129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanffy MS. Biotransformation enzymes in the rodent nasal mucosa: The value of a histochemical approach. Environ Health Perspect. 1990;85:177–186. doi: 10.1289/ehp.85-1568341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone E, Tamm A, Hill M. The production of urinary phenols by gut bacteria and their possible role in causation of large bowel cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 1976;29:1448–1454. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/29.12.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutwell RK, Bosch DK. The tumor-promoting action of phenol and related compounds for mouse skin. Cancer Res. 1959;19:413–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray HG, Thorpe WV, White K. Metabolism of derivatives of toluene. Biochemistry. 1950;46:275–278. doi: 10.1042/bj0460275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;B34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Dills RL, Bellamy GM, Kalman DA. Quantitation of o-, m- and p-cresol and deuterated analogs in human urine by gas chromatography with electron capture detection. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1997;703:105–113. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(97)00407-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fustinoni S, Mercadante R, Campo L, Scibetta L, Valla C, Foà V. Determination of urinary ortho- and meta-cresol in humans by headspace SPME gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B. 817:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MA. A household remedy misused-Fatal cresol poisoning following cutaneous absorption (A case report) Med Sci Law. 1975;15:65–66. doi: 10.1177/002580247501500114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillén MD, Errecalde MC, Salméron J, Casas C. Headspace volatile components of smoked swordfish (Xiphias gladius) and cod (Gadus morhua) detected by means of solid phase microextraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2006;94:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PTC. Propionic acid and the phenomenon of rodent forestomach tumorigenesis: A review. Food Chem Toxicol. 1992;30:333–340. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(92)90012-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CT, Lee KN, Jin QZ. Isolation and identification of volatile flavor compounds in fried bacon. J Agric Food Chem. 1983;31:336–342. [Google Scholar]

- Huff J, Haseman J, Rall D. Scientific concepts, value, and significance of chemical carcinogenesis studies. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1991;31:621–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.31.040191.003201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) Environmental Health Criteria 168: Cresols. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ito N, Fukushima S, Hagiwara A, Shibata M, Ogiso T. Carcinogenicity of butylated hydroxyanisole in F344 rats. JNCI. 1983;70:343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay K, Stieglitz L. Identification and quantification of volatile organic components in emissions of waste incineration plants. Chemosphere. 1995;30:1249–1260. [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Yang X, Yu H, Yin D. Identification of ammonia and volatile phenols as primary toxicants in a coal gasification effluent. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1999;63:399–406. doi: 10.1007/s001289900994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- Kilic M, Lindsay RC. Distribution of conjugates of alkylphenols in milk from different ruminant species. J Dairy Sci. 2005;88:7–12. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72656-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology (Kirk-Othmer) John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1997. [November 6, 2006]. Tar and pitch; pp. 1–31. Published online 2000, < www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com>. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology (Kirk-Othmer) Alkylphenols. 5th. Vol. 2. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2004. pp. 203–233. [Google Scholar]

- Lau SS, Monks TJ, Everitt JI, Kleymenova E, Walker CL. Carcinogenicity of a nephrotoxic metabolite of the “nongenotoxic” carcinogen hydroquinone. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:25–33. doi: 10.1021/tx000161g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtonen M. Phenols in whisky. Chromatographia. 1982;16:201–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lesaffer G, De Smet R, Belpaire FM, Van Vlem B, Van Hulle M, Cornelis R, Lameire N, Vanholder R. Urinary excretion of the uraemic toxin p-cresol in the rat: Contribution of glucuronidation to its metabolization. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:1299–1306. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight DM, Pereira WE, Ceazan ML, Wissmar RC. Characterization of dissolved organic materials in surface waters within the blast zone of Mount St Helens, Washington. Org Geochem. 1982;4:85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Monma-Ohtaki J, Maeno Y, Nagao M, Iwasa M, Koyama H, Isobe I, Seko-Nakamura Y, Tsuchimochi T, Matsumoto T. An autopsy case of poisoning by massive absorption of cresol a short time before death. Forensic Sci Int. 2002;126:77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(02)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morinaga Y, Fuke C, Arao T, Miyazaki T. Quantitative analysis of cresol and its metabolites in biological materials and distribution in rats after oral administration. Leg Med. 2004;6:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morville S, Scheyer A, Mirabel P, Millet M. Spatial and geographical variations of urban, suburban and rural atmospheric concentrations of phenols and nitrophenols. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2006;13:83–89. doi: 10.1065/espr2005.06.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Toxicology Program (NTP) Technical Report Series No. 203. NIH Publication No. 80-1759. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD, and Research Triangle Park, NC: 1980. Bioassay of Phenol for Possible Carcinogenicity (CAS No. 108-95-2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Toxicology Program (NTP) Technical Report Series No. 371. NIH Publication No. 90-2826. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health; Research Triangle Park, NC: 1990. Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Toluene (CAS No. 108-88-3) in F344/N Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Inhalation Studies) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Toxicology Program (NTP) Toxicity Report Series No. 9. NIH Publication No. 92-1328. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health; Research Triangle Park, NC: 1992. Toxicity Studies of Cresols (CAS Nos. 95-48-7, 108-39-4, and 106-44-5) Administered in Feed to F344/N Rats and B6C3F1 Mice. [Google Scholar]

- National Toxicology Program (NTP) Technical Report Series No. 500. NIH Publication No. 01-4434. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2000. NTP Technical Report on the Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Naphthalene (CAS No. 91-20-3) in F344/N Rats (Inhalation Studies) [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen PH, Albrechtsen HJ, Heron G, Christensen TH. In situ and laboratory studies on the fate of specific organic compounds in an anaerobic landfill leachate plume, 1. Experimental conditions and fate of phenolic compounds. J Contam Hydrol. 1995;20:27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ogata N, Matsushima N, Shibata T. Pharmacokinetics of wood creosote: Glucuronic acid and sulfate conjugation of phenolic compounds. Pharmacology. 1995;51:195–204. doi: 10.1159/000139335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piegorsch WW, Bailer AJ. Statistics for Environmental Biology and Toxicology, Section 6.3.2. Chapman and Hall; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce CH, Chen Y, Dills RL, Kalman DA, Morgan MS. Toluene metabolites as biological indicators of exposure. Toxicol Lett. 2002;129:65–76. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(01)00472-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portier CJ, Bailer AJ. Testing for increased carcinogenicity using a survival-adjusted quantal response test. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1989;12:731–737. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(89)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzbauer J, Littke R, Weigelt V. Identification of specific organic contaminants for estimating the contribution of the Elbe river to the pollution of the German Bight. Org Geochem. 2000;31:1713–1731. [Google Scholar]

- Seely JC, Haseman JK, Nyska A, Wolf DC, Everitt JI, Hailey JR. The effect of chronic progressive nephropathy on the incidence of renal tubule cell neoplasms in control male F344 rats. Toxicol Pathol. 2002;30:681–686. doi: 10.1080/01926230290166779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suriyaphan O, Drake MA, Chen XQ, Cadwallader KR. Characteristic aroma components of British Farmhouse Cheddar cheese. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:1382–1387. doi: 10.1021/jf001121l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarone RE. Tests for trend in life table analysis. Biometrika. 1975;62:679–682. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DC, Perera K, London R. Quinone methide formation from para isomers of methylphenol (cresol), ethylphenol, and isopropylphenol: Relationship to toxicity. Chem Res Toxicol. 1995;8:55–60. doi: 10.1021/tx00043a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton SF, Quigley S, Spence MJ, Banwart SA, Bottrell S, Lerner DN. Processes controlling the distribution and natural attenuation of dissolved phenolic compounds in a deep sandstone aquifer. J Contam Hydrol. 2001;53:233–267. doi: 10.1016/s0169-7722(01)00168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortajada-Genaro LA, Campíns-Falcó P, Bosch-Reig F. Unbiased spectrophotometric method for estimating phenol or o-cresol in unknown water samples. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2003;376:413–421. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-1914-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uraih LC, Maronpot RR. Normal histology of the nasal cavity and application of special techniques. Environ Health Perpect. 1990;85:187–208. doi: 10.1289/ehp.85-1568325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) Chemical Summary for Acetaldehyde. EPA/749/F-94/003a. Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Vernot EH, MacEwen JD, Haun CC, Kinkead ER. Acute toxicity and skin corrosion data for some organic and inorganic compounds and aqueous solutions. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1977;42:417–423. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(77)90019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RT. Studies in detoxication. I: The influence of (a) dose and (b) o-, m- and p-substitution on the sulphate detoxication of phenol in the rabbit. Biochem J. 1938;32:878–887. doi: 10.1042/bj0320878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woiwode W, Drysch K. Experimental exposure to toluene: Further consideration of cresol formation in man. Br J Ind Med. 1981;38:194–197. doi: 10.1136/oem.38.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ML, Tsai WJ, Yang CC, Deng JF. Concentrated cresol intoxication. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1998;40:341–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, Zhong HM, Maher N, Torres R, Leo GC, Caldwell GW, Huebert N. Bioactivation of 4-methylphenol (p-cresol) via cytochrome P450-mediated aromatic oxidation in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:1867–1876. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.006387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanysheva NYa, Balenko NV, Chernichenko IA, Babiy VF. Peculiarities of carcinogenesis under simultaneous oral administration of benzo(a)pyrene and o-cresol in mice. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;101(Suppl 3):341–344. doi: 10.1289/ehp.101-1521150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashiki M, Kojima T, Miyazaki T, Chikasue F, Ohtani M. Gas chromatographic determination of cresols in the biological fluids of a non-fatal case of cresol intoxication. Forensic Sci Int. 1990;47:21–29. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(90)90282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Wintersteen CL, Cadwallader KR. Identification and quantification of aroma-active components that contribute to the distinct malty flavor of buckwheat honey. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:2016–2021. doi: 10.1021/jf011436g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]