Abstract

Background:

The use of leukotriene antagonists (LTRAs) for asthma therapy has been associated with a significant degree of inter-patient variability in response to treatment. Some of that variability may be attributable to non-cysteinyl leukotriene type 1 receptor (CysLT1) mediated inhibitory mechanisms that have been demonstrated for this group of drugs.

Objective:

We have used a model of CysLT1 signaling in human monocytes to characterize CysLT1-dependent and CysLT1-independent anti-inflammatory activity of two chemically different, clinically relevant, LTRAs (montelukast and zafirlukast).

Results:

Using receptor desensitization experiments in monocytes and CysLT1 transfected HEK293 cells, and IL-10 and CysLT1 siRNA induced downregulation of CysLT1 expression, we showed that reported CysLT1 agonists, LTD4 and uridine diphosphate (UDP), signal through calcium mobilization, acting on separate receptors and that both pathways were inhibited by montelukast and zafirlukast. However, 3 logs higher concentrations of LTRAs were required for inhibition of UDP induced signaling. In monocytes, UDP, but not LTD4, induced IL-8 production that was significantly inhibited by both drugs at micromolar concentrations. Both LTRAs, at low micromolar concentrations, also inhibited calcium ionophore induced leukotriene (LTB4 and LTC4) production, indicating 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory activities.

Conclusion:

We report here that montelukast and zafirlukast, acting in a concentration dependent manner, can inhibit non-CysLT1 mediated, proinflammatory reactions, suggesting activities potentially relevant for inter-patient variability in response to treatment. Higher doses of currently known LTRAs or new compounds derived from this class of drugs may represent a new strategy for finding more efficient therapy for bronchial asthma.

Keywords: bronchial asthma, leukotrienes, leukotriene antagonists, monocytes, UDP

INTRODUCTION

Leukotrienes have been implicated in the pathophysiology of bronchial asthma. Drugs inhibiting leukotriene signaling such as leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs) (montelukast, pranlukast, zafirlukast) have been shown to be effective in treating this disease (1, 2). However, their use has been associated with a significant degree of inter-patient variability in response to treatment. In clinical trials, 20% to 50 % of patients receiving LTRAs could be classified as responders, showing a great heterogeneity in response to these drugs that affects effectiveness of treatment (3, 4). Much of that variability may be attributable to genetic variations and several studies reported that genetic polymorphisms in genes encoding key proteins in leukotriene pathway might influence response to LTRAs (5, 6). Another cause of variability may be associated with pharmacokinetic characteristics of the drugs used and the final individual compound plasma concentrations obtained during treatment.

All LTRAs act on the cysteinyl-leukotriene type I receptor (CysLT1) and by competitive antagonism at this receptor are believed to be responsible for control of airway inflammation, bronchoconstriction and remodeling (7, 8). However, anti-inflammatory activity of LTRAs independent of CysLT1 antagonism has recently been suggested. Montelukast reduced the expression of urokinase plasminogen activator receptor and the secretion of metalloproteinase 9 in human eosinophils in vitro (9) and inhibited tumor necrosis factor alpha mediated interleukin-8 expression in U937 cells through mechanisms distinct from CysLT1 antagonism (10). Interestingly, it has also been shown that montelukast may have a novel inhibitory effect on 5-lipoxygenase activity (11) and transport of leukotrienes by the multidrug resistance protein ABCC4 (12), suggesting a broader mechanism of action for this drug. Non-CysLT1 related mechanisms of LTRA actions might present another level of variability in response to treatment in asthmatic patients. Some of these non-CysLT1 related activities of LTRAs may be compound specific or may dependend on drug concentration or the presence of a particular inflammatory pathway in asthmatic patients and therefore clinically significant effects of treatment may be observed only in some but not all treated subjects.

We have previously shown that CysLT1 is the predominantly expressed leukotriene receptor in human elutriated monocytes and that leukotriene D4 (LTD4) acting through CysLT1 can induce activation and chemotaxis of these cells (13). In the current study we have used this model of CysLT1 signaling in human monocytes to characterize CysLT1-dependent and CysLT1-independent inhibitory activity of two chemically different, clinically relevant, LTRAs (montelukast and zafirlukast) and to define the pathways of their inhibitory action.

METHODS

Materials

LTD4, montelukast and zafirlukast (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), calcium ionophore A23187 (EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ), uridine diphosphate (UDP), MRS 2578, DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), human recombinant IL-10 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), were obtained from the manufacturers.

Cell culture

Human elutriated monocytes from healthy donors were obtained by an institutional review board-approved protocol from the NIH Blood Bank (Bethesda, MD), resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 2 mmol/L L-glutamine (all Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and allowed to rest overnight before experiments at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in DMEM medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS.

Calcium mobilization assay

Calcium mobilization experiments were conducted using a FLIPR Calcium 3 assay kit (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were plated into Poly-L–Lysine coated 96-well plates and incubated in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10 mmol/L HEPES and FLIPR 3 assay reagent. After incubation for 1 hour at 37°C, fluorescence was measured every 4 sec. using the FlexStation (Molecular Devices).

HEK293 cells were grown in 75 cm2 flasks and transiently transfected with empty pcDNA 3.1 vector or CysLT1 expression vector (UMR cDNA Resource Center, Rolla, MO) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in serum free medium (Opti-MEM I, Invitrogen), transferred to Poly-L-Lysine coated 96 well plates after 24 hours and used for calcium mobilization experiments after another 24 hours of incubation.

CysLT1, CysLT2 and P2Y6 knockdown

For CysLT1, CysLT2 and P2Y6 knockdown experiments Silencer Select pre-designed siRNA (CysLT1: 5′GGAAAAGGCUGUCUACAUUtt; CysLT2: GCACAAUUGAAAACUUCAAtt; P2Y6: GAAGCUCACCAAAAACUAUtt) and Silencer Select Negative Control siRNA were used (Ambion, Austin, TX). Elutriated monocytes (5×106) were nucleofected with 4 μg of negative control or specific siRNA using a Human Monocyte Nucleofector kit (Amaxa, Cologne, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 24 hours, media was replaced and cells were used for functional studies.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using QIA Shredder columns and RNeasy mini kit and was treated with DNase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). mRNA expression for selected genes was measured using real-time PCR performed on an ABI Prism 7900 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the following commercially available probe and primers sets (Applied Biosystems): CysLT1-Hs00272624_s1, CysLT2-Hs 00252658_s1, P2Y6-Hs00602548_m1. Reverse transcription and PCR were performed using an RT kit and TaqMan Universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer's directions. Relative gene expression was normalized to GAPDH transcripts and calculated as a fold change compared with control.

ELISA

For interleukin-8 (IL-8) determination, monocytes (2 ×106) were stimulated with LTD4 (100 nmol/L) or UDP (100 μmol/L) for 2 and 6 hours in the presence or absence of inhibitors. Supernatants were stored at −20°C until analysis by commercial Quantikine ELISA (R&D Systems) for IL-8.

Determination of LTB4, LTC4 and PGE2 synthesis

Monocytes (1 × 106) were resuspended in culture medium without FBS, preincubated with different concentrations of montelukast, zafirlukast or vehicle control (DMSO) and stimulated with calcium ionophore A23187 (1 μmol/L) or DMSO for 30 min. Supernatants were collected by centrifugation and frozen at −80°C for leukotriene measurement. For intracellular leukotriene determination, elutriated monocytes (2 × 106) were used and reactions were stopped by addition of cold PBS and cells were collected by centrifugation at 4 °C. Cells were lysed by freezing (3x), followed by lipid purification using an SPE (C-18) cartridge (Cayman Chem, Ann Arbor, MI) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Purified samples were resuspended in EIA buffer and assayed directly. The concentration of LTB4, LTC4 and PGE2 produced spontaneously and after stimulation was assayed by means of competitive enzyme immunosorbent assay (Cayman Chem.) according to manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA or paired and unpaired Student's t tests, as appropriate. Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Leukotriene antagonists inhibit LTD4 and UDP induced calcium flux

It has been suggested that CysLT1 has a dual cysLTs/ UDP specificity (14). To investigate a role of LTRAs in CysLT1 mediated reactions, the responsiveness of human monocytes to LTD4 and UDP was evaluated by intracellular calcium flux measurement. As shown in Figure 1, monocytes responded in a concentration dependent manner to LTD4 and UDP. However, the most effective concentration of UDP inducing calcium flux was 3 logs higher (10−4 mol/L) than the most effective concentration of LTD4 (10−7−10−6 mol/L). CysLT1 antagonists (montelukast and zafirlukast) were used to analyze whether LTRAs similarly inhibit UDP and LTD4 signaling in monocytes. Both antagonists inhibited (Figure 2) LTD4 and UDP induced calcium flux in monocytes in a concentration dependent manner. However, as only low nanomolar concentrations of montelukast and zafirlukast were required to fully inhibit LTD4 induced calcium flux, much higher (10−5−10−4 mol/L) concentrations of antagonists were required to inhibit UDP-induced calcium changes.

Figure 1.

LTD4 and UDP induce calcium mobilization in monocytes. Monocytes were prepared and stimulated with different concentrations of LTD4 (open squares) or UDP (open diamonds) and calcium release was measured, as indicated in Methods. Data are presented as means ± SD from 3 separate experiments each performed in triplicate.

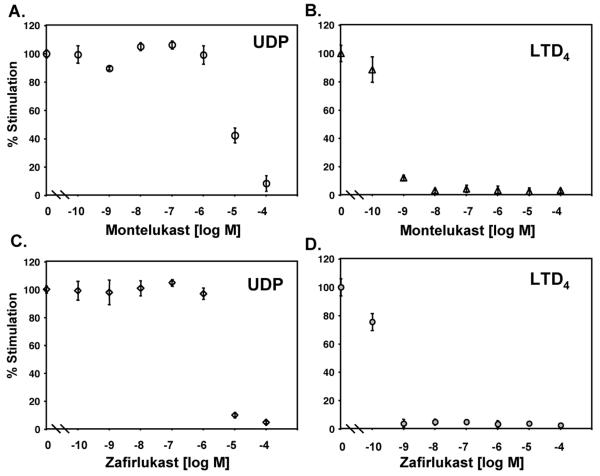

Figure 2.

Montelukast and zafirlukast inhibit UDP and LTD4 induced calcium mobilization in monocytes. Monocytes were stimulated with UDP (100 μmol/L) (A, C) or LTD4 (100 nmol/L) (B, D) in the presence of increasing concentrations of montelukast (A, B), zafirlukast (C, D) or vehicle control (10 min. pretreatment). Results are shown as the percentage of peak fluorescence obtained in cells stimulated without inhibitors. The means ± SD from three independent experiments are presented.

LTD4 and UDP signal through separate receptors in monocytes

To further characterize responsiveness of human monocytes to LTD4 and UDP, the submaximally effective concentrations of LTD4 (10−7 mol/L) and UDP (10−4 mol/L) were used to analyze the pattern of calcium signaling and desensitization. LTD4 induced in monocytes (Figure 3A) a rapid elevation of intracellular calcium levels that relatively quickly fell to baseline. UDP also rapidly increased intracellular calcium levels but these were sustained for 10-20 sec. and then decreased to baseline. This different pattern of calcium changes induced by UDP in comparison to LTD4, suggested that those compounds could activate different receptors or signaling pathways. In agreement with the above observation, stimulation with LTD4 (10−7 mol/L) potently desensitized monocytes to subsequent stimulation with the same concentration of LTD4 (10−7) (as expected for homologous desensitization), but did not have any effect on subsequent UDP exposure, suggesting again that UDP could act through a separate receptor, not CysLT1. When cells were stimulated with UDP, full desensitization of calcium signaling was observed for the subsequent UDP exposure (homologous desensitization) and partial inhibition of signaling to subsequent LTD4 stimulation. To determine whether LTD4 and UDP could activate CysLT1, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with the human CysLT1 construct. HEK293 cells did not express CysLT1 mRNA and when transfected with empty pcDNA 3.1 vector did not show calcium responses after LTD4 stimulation up to 10−6 mol/L concentration (not shown). In cells transfected with CysLT1 (Figure 3B), LTD4 induced calcium flux with a pattern similar to that observed in monocytes and full homologous desensitization to LTD4 was also present. However, both empty vector and CysLT1 transfected HEK293 cells responded to UDP with potent calcium flux, with the most effective concentration 10−4 mol/L. When the desensitization experiments were carried out, a similar level of homologous desensitization to UDP was observed in empty control and CysLT1 transfected cells. Interestingly, the same pattern of heterologous desensitization as in monocytes was identified in CysLT1 transfected cells, partial desensitization by UDP to subsequent LTD4 stimulation and no desensitization by LTD4 to subsequent UDP exposure. All these data suggested that UDP induced calcium flux through a separate receptor, not CysLT1. It has been shown that UDP can induce calcium flux in several cell systems acting through nucleotide G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), with P2Y6 being the most selective for UDP. We confirmed the presence of P2Y6 mRNA in monocytes, but the level of expression of P2Y6 mRNA in HEK293 cells was very low (data not shown), suggesting that UDP could activate calcium flux acting through this or other nucleotide receptors in these cells. UDP (100 μM) induced a calcium flux in untransfected HEK cells which was not inhibited by the P2Y6 inhibitor, MRS2578 (5 μM). MRS2578 inhibited in a concentration dependent manner both, UDP- as well as LTD4-induced calcium flux in monocytes when used at micromolar concentrations (Figure 4). We have previously reported that IL-10 downregulates CysLT1 expression and signaling in human monocytes (15). Monocytes were exposed to IL-10 (20 ng/ml) overnight to downregulate CysLT1 and calcium flux to LTD4 and UDP was evaluated. IL-10 downregulated CysLT1 mRNA (measured by real-time PCR) and inhibited LTD4 induced calcium flux, while UDP signaling was not significantly affected (Figure 5A), suggesting that UDP does not signal through CysLT1 in monocytes. To further confirm this observation, CysLT1 expression was specifically downregulated by siRNA as previously described (15) and calcium flux was measured in response to different concentrations of LTD4 and UDP. As expected, in CysLT1 siRNA treated cells, LTD4 induced calcium flux was significantly inhibited, in contrast to UDP induced signaling which remained similar in CysLT1 siRNA and control cells (Figure 5B). Treatment of cells with siRNA directed at CysLT2 reduced CysLT2 mRNA by 87% but did not reduce LTD4- or UDP-induced calcium flux (data not shown). To analyze whether UDP signals through P2Y6 in monocytes, P2Y6 was knocked down using siRNA and response to LTD4 and UDP was measured. P2Y6 mRNA was knocked down by 85% (4 measurements). In P2Y6 siRNA treated cells UDP-induced calcium flux was inhibited whereas LTD4-induced signaling was not affected (Figure 6), showing that in fact, P2Y6 may be one of the target receptors for UDP-induced signaling in monocytes.

Figure 3.

Desensitization effects in LTD4 and UDP stimulated monocytes and CysLT1transfected HEK293 cells. Representative traces of calcium flux induced by repeated exposure to LTD4 (100 nmol/L) and UDP (100 μmol/L) in monocytes (A) and CysLT1 transfected HEK293 cells (B). Data from one of three separate experiments, each with similar results, are shown.

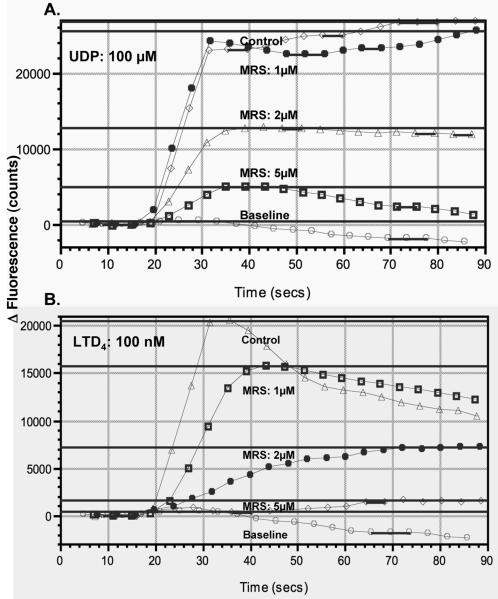

Figure 4.

The effect of P2Y6 inhibitor, MRS2578 on UDP- and LTD4-induced calcium flux in monocytes. Representative traces of calcium flux induced by exposure to UDP (100 μmol/L) and LTD4 (100 nmol/L) in the presence of increasing concentrations of MRS2578 (MRS) or vehicle control. Data from one of three separate experiments, each with similar results, are shown.

Figure 5.

Down-regulation of CysLT1 did not affect UDP induced calcium mobilization in monocytes. (A) Monocytes were incubated with or without IL-10 (20 ng/ml) overnight and calcium release was measured in response to different concentrations of LTD4 and UDP as described in the Methods section. (B) Monocytes were nucleofected with CysLT1 siRNA or negative control oligonucleotides (Con) as described in the Methods section, cultured for 24 hours and calcium flux was measured in response to LTD4 and UDP. Data are presented as means ± SD from 3 separate experiments performed in triplicate.

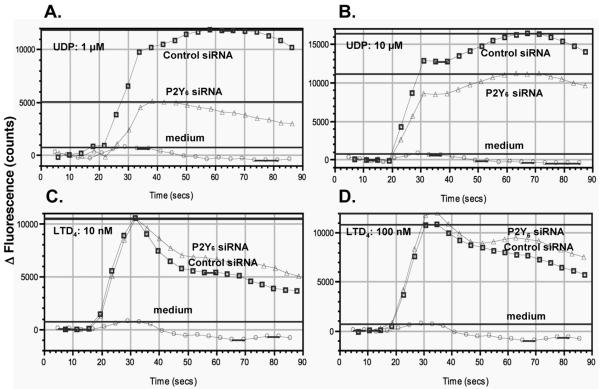

Figure 6.

Knock down of P2Y6 did not affect LTD4 induced signaling in monocytes. Monocytes were nucleofected with P2Y6 siRNA or negative control oligonucleotides (Control) as described in the Methods section, cultured for 24 hours and calcium flux was measured in response to different concentrations of UDP (A, B) and LTD4 (C, D). Representative traces of calcium flux from one of three separate experiments, each with similar results, are shown.

All of these data suggest that in human monocytes, LTD4 and UDP activate separate receptors, LTD4 induces calcium flux through CysLT1 and UDP signals at least in part through P2Y6.

Leukotriene antagonist inhibits UDP induced IL-8 production

It has been reported that UDP mediates IL-8 production in monocytic THP-1 cells (16). To determine whether LTRAs may inhibit, apart from intracellular calcium flux, other UDP induced functions, monocytes were stimulated with LTD4 or UDP and synthesis of IL-8 was measured as described in Methods section. UDP, but not LTD4, induced IL-8 production in a time dependent manner (Figure 7A) that was significantly inhibited by the P2Y6 inhibitor, MRS2578 (10 μmol/L). Montelukast and zafirlukast also inhibited IL-8 production in a concentration dependent manner (Figure 7B). These data further confirm that LTD4 and UDP signal differently in human monocytes and that LTRAs may significantly affect UDP-induced activation of these cells. It has been recently reported that in human mast cells CysLT1 knock down inhibited LTD4 and UDP induced chemokine generation (17). In contrast, we did not observe significant changes in chemokine (IL-8) generation in CysLT1 siRNA treated monocytes in comparison to control siRNA treated cells (data not shown). This suggests that UDP and CysLTs may signal differently in different types of cells (mast cells and monocytes), probably reflecting differences in GPCR expression.

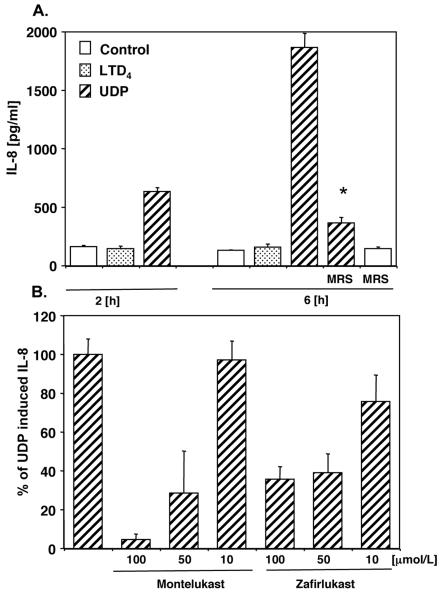

Figure 7.

Montelukast and zafirlukast inhibit UDP induced IL-8 production in monocytes. (A) Monocytes were preincubated with MRS2578 or vehicle control for 30 min. and stimulated with LTD4(100 nmol/L) or UDP (100 μmol/L). Supernatants were collected after 2 h and 6 h and IL-8 expression was measured. (B) Monocytes were preincubated with different concentrations of LTRAs, stimulated with UDP and IL-8 expression was measured after 6 hours. Data are presented as percentage of UDP induced IL-8 production from cells pretreated with vehicle control. Means ± SD from 3 separate experiments are presented. * p < 0.001; Student's t test.

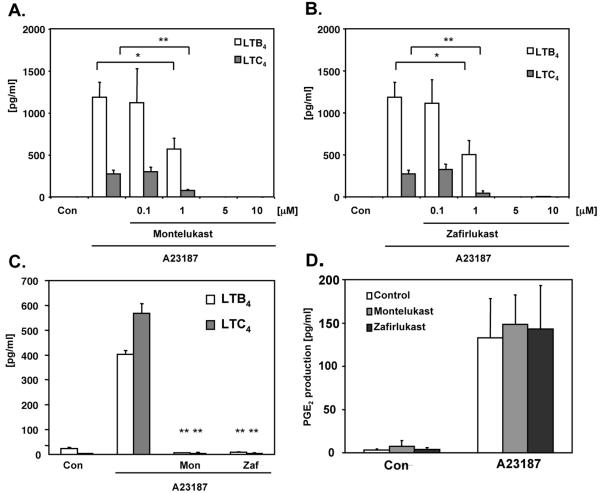

Leukotriene antagonists inhibit leukotriene production

To establish whether LTRAs may affect 5-LO activity and leukotriene production, monocytes were stimulated with calcium ionophore A23187, and synthesis of LTB4 and LTC4 was measured. Stimulated monocytes produced significant levels of both leukotrienes that were inhibited by pretreatment with montelukast (Figure 8A) and zafirlukast (Figure 8B) in a concentration dependent fashion. Both antagonists at 5 μmol/L concentration fully inhibited leukotriene production, suggesting that 5-LO could be directly affected by the treatment. To exclude a possibility that LTRAs affect arachidonic acid synthesis by phospholipase A2, PGE2 as a product of cyclooxygenase pathway of arachidonic acid cascade was measured in the same experiments. Neither montelukast nor zafirlukast (5 mol/L) inhibited calcium ionophore induced PGE2 generation (Figure 8D). To further analyze whether LTRAs inhibit production of leukotrienes and not out of the cell transport, monocytes were stimulated with calcium ionophore and intracellular levels of LTB4 and LTC4 were measured as described in the Methods section. Calcium ionophore stimulation produced detectable intracellular levels of both leukotrienes (Figure 8C) that were inhibited by pretreatment with montelukast and zafirlukast, indicating that LTRAs may significantly downregulate production of leukotrienes in human monocytes.

Figure 8.

Montelukast and zafirlukast inhibit leukotriene synthesis in monocytes. Monocytes were preicubated with different concentrations of montelukast (A) and zafirlukast (B) (10 min) or vehicle control, stimulated with calcium ionophore A23187 (1 μmol/L) and levels of LTB4, LTC4 and PGE2 (D) released were measured. (C) Cells were preincubated with montelukast (Mon) and zafirlukast (Zaf) (5 μmol/L) and intracellular levels of LTB4 and LTC4 were measured as described in Methods. The means ± SD from 3 donors, performed in triplicate are shown. * p < 0.01 or ** p < 0.001 for A23187 stimulated cells with versus without inhibitor.

DISCUSSION

We present here evidence that so called “selective CysLT1 antagonists” montelukast and zafirlukast possess concentration-dependent, non-CysLT1 mediated inhibitory activities in primary human monocytes. Both drugs effectively inhibited LTD4 induced signaling at the nanomolar concentration range, in agreement with CysLT1 antagonist activity reported in previously published studies (18, 19). Interestingly, montelukast and zafirlukast, acting at low micromolar concentrations inhibited also LTC4 and LTB4 synthesis, probably through a direct inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase. It has been suggested that montelukast may directly inhibit 5-LO activity, binding to an undefined allosteric site on 5-LO (11). In our study, both LTRAs montelukast and zafirlukast, similarly inhibited leukotriene synthesis but not PGE2 generation, suggesting that this 5-LO inhibitory activity is not specific for montelukast only, but it can be applied to other LTRAs as well. The next proinflammatory pathway, inhibited in our study by both compounds at higher micromolar concentrations, is UDP-induced signaling and IL-8 production. Extracellular nucleotides, such as UTP and UDP, have been shown to activate phospholipase C and intracellular calcium mobilization in differentiated U937 cells, through purine P2Y receptors and those effects were inhibited by micromolar concentrations of montelukast and pranlukast (20). We validated these observations in a human primary cell system and we showed that such an inhibition of signaling may have functional consequences for cell activation, measured at the level of UDP induced IL-8 production. We report here that two chemically different LTRAs might possess, in addition to CysLT1 antagonism, anti-inflammatory activities in primary human cells. The fact that these additional inhibitory activities are strongly related to the drug concentration might have potential clinical relevance. The LTRAs in contrast to many other drugs, are believed to require membrane transporters for their absorption after oral administration (21-23). In addition, other features, such as strong binding to plasma albumin (> 99%) and extensive hepatic metabolism, suggest that biavailability of those drugs might be affected by pharmacogenetic and pharmakokinetic factors resulting in variabilty of plasma drug concentration and variability in response to treatment. Although there are no published population based data demonstrating pharmacogenetic influence on LTRAs plasma concentrations, case reports showed significant variations in montelukast plasma levels in healthy subjects (24). In addition, it has been recently shown that genetic variation of OATP2B1, a membrane transport protein was associated with variable montelukast plasma concentrations and variable response to treatment in patients with asthma (25). The maximum plasma concentration after orally administered 10 mg of montelukast ranged from 0.57 to 0.63 μmol/L in healthy female and male subjects, respectively (26) and reached 0.80 μmol/L following administration of a 10 mg of chewable tablet in adults and a 5 mg chewable tablet in 9 to 14 years old children (27). These concentrations are very close to concentrations of montelukast and zafirlukast required for leukotriene synthesis inhibition (1-5 μmol/L) in our study. Having in mind potential genetically driven variability in drug absorption and metabolism, it is plausible to consider that in some patients even after administration of standard dose of LTRAs, inhibition of the leukotriene synthesis pathway might be observed in addition to CysLT1 antagonism. The clinical relevance of additional inhibitory activity of LTRAs on 5-LO has not been addressed yet. In a placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of montelukast in asthmatic patients, doses from 10 mg to 200 mg daily have been analyzed and no dose-response relationship for asthma symptoms control and spirometry was observed (28). However, in patients treated with 100 and 200 mg (calculated maximum plasma concentration above 3 and 7 μmol/L, respectively (29)) both morning and evening peak expiratory flow rates showed nearly two times higher improvement than in patients receiving lower doses, suggesting that higher doses of this drug could have an additional impact on asthma treatment. Inhibition of UDP signaling by LTRAs required higher micromolar concentrations (10 -100 μmol/L) in our study. The maximum plasma concentration exceeded 25 μmol/L after oral administration of 800 mg of montelukast, a dose that was still well tolerated, (29) but clinical relevance of such doses has not been tested. It has been shown that LTRAs may also affect other non CysLT1 mediated pathways in human primary cells. Montelukast inhibited eosinophil protease activity (9) and pranlukast supressed LPS-induced interleukin-6 production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, (30) both effects were observed at micromolar drug concentrations. All these data strongly suggest that in addition to CysLT1 antagonism, several other proinflammatory pathways may be affected by LTRAs treatment and depending on plasma drug concentration variable response to treatment may be expected.

It has been suggested that CysLT1 expressed on human mast cells is also a pyrimidinergic receptor and that it responds to UDP stimulation in addition to CysLTs (14, 31). In our study, human monocytes responded to LTD4 and UDP, but with characteristics suggesting UDP acting through separate receptors. First of all, 3 logs higher concentrations (10−4 mol/L) of UDP were required to submaximally activate calcium flux in monocytes than reported in the study by Mellor et al. (14). Although, UDP signaling in monocytes was inhibited by LTRAs, much higher concentrations of LTRAs were needed. Almost every GPCR studied undergoes desensitization following agonist stimulation, an important process that is crucial for turning off the receptor mediated signaling pathway. As expected, CysLT1 underwent LTD4-induced homologous desensitization in monocytes, but we did not observe desensitization of UDP induced calcium flux subsequent to LTD4 treatment, a phenomenon that should be present when both agonists acted on the same GPCR. The similar observation was reported in differentiated U937 cells, (32) where it has been shown that CysLT1 receptor desensitization and trafficking are differentially regulated by LTD4 and extracelluar nucleotides, including UDP. Capra et al. (32) showed that CysLT1 may be a target for extracellular nucleotide-induced heterologous desentization, a potential feedback mechanism in inflammation. The presence of this heterologous desensitization mechanism was demonstrated for the first time in human primary cells in our study. UDP signals effectively through calcium flux acting on P2Y6 in human cells (33). Because human monocytes express mRNA for CysLT1 and P2Y6, to further support the observation that UDP does not signal through CysLT1 in monocytes, we downregulated the CysLT1 expression either by IL-10 preincubation or specific CysLT1 siRNA, showing the specific decrease in LTD4 induced signaling, without an effect on UDP induced calcium mobilization. Knock down of P2Y6 decreased UDP-induced calcium flux but did not affect LTD4 induced signaling. All of these data suggest that in human cells UDP is not a CysLT1 agonist, but it may potentially signal through a different GPCR. In fact, a newly described cysLT receptor, GPR17, was shown to be a dual UDP/cysLTs receptor (34). We have shown previously that GPR17 is not expressed in human monocytes (13), excluding this receptor as a potential target for UDP in monocytes. Interestingly, the presence of GPR17 was detected in mast cell line LAD2, an observation that could potentially explain cysLTs receptor related signaling induced by UDP in mast cells (35). It has also been suggested that additional, not characterized yet, cysLTs receptor may be expressed in mast cells (35).

The described inhibitory activity of LTRAs on the 5-LO pathway and extracellular nucleotide induced signaling may be relevant for designing new asthma treatment strategies. LTB4, another product of the 5-LO pathway, has been reported to contribute to the recruitment and activation of neutrophils and eosinophils and play an important role in asthma exacerbations (36). Extracellular nucleotides serve as a danger signal to alert the immune system of tissue damage. It has been shown in a murine model that extracellular ATP triggers and maintains asthmatic airway inflammation by activating dendritic cells (37). UDP may mediate microglial phagocytosis (38) and may play a role in innate immune responses, but its significance for asthmatic inflammation is not known. Higher doses of currently known LTRAs or new compounds derived from this class of drugs may represent a new strategy for finding more efficient therapy for bronchial asthma.

Abbreviations

- cysLTs

cysteinyl leukotrienes

- CysLT1

cysteinyl leukotriene type 1 receptor

- LTB4

leukotriene B4

- LTC4

leukotriene C4

- LTD4

leukotriene D4

- 5-LO

5 lipoxygenase

- UDP

uridine diphosphate

- LTRAs

cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonists

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

REFERENCES

- 1.Spector SL, Smith LJ, Glass M. Effects of 6 weeks of therapy with oral doses of ICI 204,219, a leukotriene D4 receptor antagonist, in subjects with bronchial asthma. ACCOLATE Asthma Trialists Group. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1994;150:618–623. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.3.8087328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiss TF, Chervinsky P, Dockhorn RJ, Shingo S, Seidenberg B, Edwards TB. Montelukast, a once-daily leukotriene receptor antagonist, in the treatment of chronic asthma: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial. Montelukast Clinical Research Study Group. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998;158:1213–1220. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.11.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malmstrom K, Rodriguez-Gomez G, Guerra J, Villaran C, Pineiro A, Wei LX, Seidenberg BC, Reiss TF. Oral montelukast, inhaled beclomethasone, and placebo for chronic asthma. A randomized, controlled trial. Montelukast/Beclomethasone Study Group. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999;130:487–495. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szefler SJ, Phillips BR, Martinez FD, Chinchilli VM, Lemanske RF, Strunk RC, Zeiger RS, Larsen G, Spahn JD, Bacharier LB, Bloomberg GR, Guilbert TW, Heldt G, Morgan WJ, Moss MH, Sorkness CA, Taussig LM. Characterization of within-subject responses to fluticasone and montelukast in childhood asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005;115:233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.In KH, Asano K, Beier D, Grobholz J, Finn PW, Silverman EK, Silverman ES, Collins T, Fischer AR, Keith TP, Serino K, Kim SW, De Sanctis GT, Yandava C, Pillari A, Rubin P, Kemp J, Israel E, Busse W, Ledford D, Murray JJ, Segal A, Tinkleman D, Drazen JM. Naturally occurring mutations in the human 5-lipoxygenase gene promoter that modify transcription factor binding and reporter gene transcription. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:1130–1137. doi: 10.1172/JCI119241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lima JJ, Zhang S, Grant A, Shao L, Tantisira KG, Allayee H, Wang J, Sylvester J, Holbrook J, Wise R, Weiss ST, Barnes K. Influence of leukotriene pathway polymorphisms on response to montelukast in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006;173:379–385. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1412OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters-Golden M, Henderson WR., Jr. Leukotrienes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1841–1854. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capra V, Thompson MD, Sala A, Cole DE, Folco G, Rovati GE. Cysteinyl-leukotrienes and their receptors in asthma and other inflammatory diseases: critical update and emerging trends. Med. Res. Rev. 2007;27:469–527. doi: 10.1002/med.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langlois A, Ferland C, Tremblay GM, Laviolette M. Montelukast regulates eosinophil protease activity through a leukotriene-independent mechanism. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006;118:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tahan F, Jazrawi E, Moodley T, Rovati GE, Adcock IM. Montelukast inhibits tumour necrosis factor-alpha-mediated interleukin-8 expression through inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB p65-associated histone acetyltransferase activity. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2008;38:805–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.02963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramires R, Caiaffa MF, Tursi A, Haeggstrom JZ, Macchia L. Novel inhibitory effect on 5-lipoxygenase activity by the anti-asthma drug montelukast. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;324:815–821. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rius M, Hummel-Eisenbeiss J, Keppler D. ATP-dependent transport of leukotrienes B4 and C4 by the multidrug resistance protein ABCC4 (MRP4) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;324:86–94. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.131342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woszczek G, Chen LY, Nagineni S, Kern S, Barb J, Munson PJ, Logun C, Danner RL, Shelhamer JH. Leukotriene D(4) induces gene expression in human monocytes through cysteinyl leukotriene type I receptor. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008;121:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.013. e211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mellor EA, Maekawa A, Austen KF, Boyce JA. Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 is also a pyrimidinergic receptor and is expressed by human mast cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2001;98:7964–7969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141221498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woszczek G, Chen LY, Nagineni S, Shelhamer JH. IL-10 inhibits cysteinyl leukotriene-induced activation of human monocytes and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2008;180:7597–7603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warny M, Aboudola S, Robson SC, Sevigny J, Communi D, Soltoff SP, Kelly CP. P2Y(6) nucleotide receptor mediates monocyte interleukin-8 production in response to UDP or lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:26051–26056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Y, Borrelli L, Bacskai BJ, Kanaoka Y, Boyce JA. P2Y6 receptors require an intact cysteinyl leukotriene synthetic and signaling system to induce survival and activation of mast cells. J. Immunol. 2009;182:1129–1137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch KR, O'Neill GP, Liu Q, Im DS, Sawyer N, Metters KM, Coulombe N, Abramovitz M, Figueroa DJ, Zeng Z, Connolly BM, Bai C, Austin CP, Chateauneuf A, Stocco R, Greig GM, Kargman S, Hooks SB, Hosfield E, Williams DL, Jr., Ford-Hutchinson AW, Caskey CT, Evans JF. Characterization of the human cysteinyl leukotriene CysLT1 receptor. Nature. 1999;399:789–793. doi: 10.1038/21658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarau HM, Ames RS, Chambers J, Ellis C, Elshourbagy N, Foley JJ, Schmidt DB, Muccitelli RM, Jenkins O, Murdock PR, Herrity NC, Halsey W, Sathe G, Muir AI, Nuthulaganti P, Dytko GM, Buckley PT, Wilson S, Bergsma DJ, Hay DW. Identification, molecular cloning, expression, and characterization of a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:657–663. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mamedova L, Capra V, Accomazzo MR, Gao ZG, Ferrario S, Fumagalli M, Abbracchio MP, Rovati GE, Jacobson KA. CysLT1 leukotriene receptor antagonists inhibit the effects of nucleotides acting at P2Y receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005;71:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein PR. Chemistry and structure-activity relationships of leukotriene receptor antagonists. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998;157:S220–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarvis B, Markham A. Montelukast: a review of its therapeutic potential in persistent asthma. Drugs. 2000;59:891–928. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059040-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunn CJ, Goa KL. Zafirlukast: an update of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in asthma. Drugs. 2001;61:285–315. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lima JJ. Treatment heterogeneity in asthma: genetics of response to leukotriene modifiers. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2007;11:97–104. doi: 10.1007/BF03256228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mougey EB, Feng H, Castro M, Irvin CG, Lima JJ. Absorption of montelukast is transporter mediated: a common variant of OATP2B1 is associated with reduced plasma concentrations and poor response. Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 2009;19:129–138. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32831bd98c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng H, Leff JA, Amin R, Gertz BJ, De Smet M, Noonan N, Rogers JD, Malbecq W, Meisner D, Somers G. Pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and safety of montelukast sodium (MK-0476) in healthy males and females. Pharm. Res. 1996;13:445–448. doi: 10.1023/a:1016056912698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knorr B, Larson P, Nguyen HH, Holland S, Reiss TF, Chervinsky P, Blake K, van Nispen CH, Noonan G, Freeman A, Haesen R, Michiels N, Rogers JD, Amin RD, Zhao J, Xu X, Seidenberg BC, Gertz BJ, Spielberg S. Montelukast dose selection in 6- to 14-year-olds: comparison of single-dose pharmacokinetics in children and adults. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1999;39:786–793. doi: 10.1177/00912709922008434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altman LC, Munk Z, Seltzer J, Noonan N, Shingo S, Zhang J, Reiss TF. A placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of montelukast, a cysteinyl leukotriene-receptor antagonist. Montelukast Asthma Study Group. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1998;102:50–56. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoors DF, De Smet M, Reiss T, Margolskee D, Cheng H, Larson P, Amin R, Somers G. Single dose pharmacokinetics, safety and tolerability of MK-0476, a new leukotriene D4-receptor antagonist, in healthy volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1995;40:277–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb05785.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ichiyama T, Hasegawa S, Umeda M, Terai K, Matsubara T, Furukawa S. Pranlukast inhibits NF-kappa B activation in human monocytes/macrophages and T cells. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2003;33:802–807. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mellor EA, Austen KF, Boyce JA. Cysteinyl leukotrienes and uridine diphosphate induce cytokine generation by human mast cells through an interleukin 4-regulated pathway that is inhibited by leukotriene receptor antagonists. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:583–592. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Capra V, Ravasi S, Accomazzo MR, Citro S, Grimoldi M, Abbracchio MP, Rovati GE. CysLT1 receptor is a target for extracellular nucleotide-induced heterologous desensitization: a possible feedback mechanism in inflammation. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:5625–5636. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Boeynaems JM, Barnard EA, Boyer JL, Kennedy C, Knight GE, Fumagalli M, Gachet C, Jacobson KA, Weisman GA. International Union of Pharmacology LVIII: update on the P2Y G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors: from molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology to therapy. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58:281–341. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ciana P, Fumagalli M, Trincavelli ML, Verderio C, Rosa P, Lecca D, Ferrario S, Parravicini C, Capra V, Gelosa P, Guerrini U, Belcredito S, Cimino M, Sironi L, Tremoli E, Rovati GE, Martini C, Abbracchio MP. The orphan receptor GPR17 identified as a new dual uracil nucleotides/cysteinyl-leukotrienes receptor. EMBO J. 2006;25:4615–4627. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paruchuri S, Jiang Y, Feng C, Francis SA, Plutzky J, Boyce JA. Leukotriene E4 activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and induces prostaglandin D2 generation by human mast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:16477–16487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705822200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gelfand EW, Dakhama A. CD8+ T lymphocytes and leukotriene B4: novel interactions in the persistence and progression of asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006;117:577–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.12.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Idzko M, Hammad H, van Nimwegen M, Kool M, Willart MA, Muskens F, Hoogsteden HC, Luttmann W, Ferrari D, Di Virgilio F, Virchow JC, Jr., Lambrecht BN. Extracellular ATP triggers and maintains asthmatic airway inflammation by activating dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 2007;13:913–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koizumi S, Shigemoto-Mogami Y, Nasu-Tada K, Shinozaki Y, Ohsawa K, Tsuda M, Joshi BV, Jacobson KA, Kohsaka S, Inoue K. UDP acting at P2Y6 receptors is a mediator of microglial phagocytosis. Nature. 2007;446:1091–1095. doi: 10.1038/nature05704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]