Abstract

High-frequency ultrasound (HFU) offers a means of investigating biological tissue at the microscopic level. High-frequency, three-dimensional (3D) quantitative-ultrasound (QUS) methods were developed to characterize freshly-dissected lymph nodes of cancer patients. 3D ultrasound data were acquired from lymph nodes using a 25.6-MHz center-frequency transducer. Each node was inked prior to tissue fixation to recover orientation after sectioning for 3D histological evaluation. Backscattered echo signals were processed using 3D cylindrical regions-of-interest to yield four QUS estimates associated with tissue microstructure (i.e., effective scatterer size, acoustic concentration, intercept, and slope). QUS estimates were computed following established methods using two scattering models. In this study, 46 lymph nodes acquired from 27 patients diagnosed with colon cancer were processed. Results revealed that fully-metastatic nodes could be perfectly differentiated from cancer-free nodes using slope or scatterer-size estimates. Specifically, results indicated that metastatic nodes had an average effective scatterer size (i.e., 37.1 ± 1.7 um) significantly larger (p <0.05) than that in cancer-free nodes (i.e., 26 ± 3.3 um). Therefore, the 3D QUS methods could provide a useful means of identifying small metastatic foci in dissected lymph nodes that might not be detectable using current standard pathology procedures.

Keywords: High-frequency ultrasound, quantitative ultrasound, lymph nodes, micrometastases, colon cancer

INTRODUCTION

High-frequency (i.e. >15 MHz) ultrasound (HFU) research is attracting considerable interest because its short wavelengths (e.g., 100 μm at 15 MHz) and small focal-zone beam diameters provide fine-resolution images. Studies have demonstrated the unique ability of HFU systems to image shallow or low-attenuation tissues for biomedical applications. For example, HFU already has been successful for small-animal (Turnbull, 2000; Turnbull and Foster, 2002; Aristizábal et al, 1998), ocular (Silverman et al, 2008, 1995), intravascular (de Korte et al, 2000; Saijo et al, 2004), and dermatological imaging (Vogt and Ermert, 2007; Huang et al, 2007).

Most human lymph nodes have sizes ranging from 2 to 8 mm in diameter, although larger sizes sometimes are encountered, e.g., in the case of node-filling metastatic cancers. Therefore, lymph nodes typically are small enough to be imaged in their entirety in three-dimensions (3D) using HFU. The long-term objective of our lymph-node studies is to develop HFU imaging methods that are capable of detecting small nodal metastases using echo-signal data from freshly-excised nodes of patients who have known primary cancers in neighboring organs (e.g., breast, colon, stomach, etc.). In routine pathology procedures, this method would direct the pathologist to suspicious regions that might be overlooked in conventional histology. In sentinel-node procedures, the method would serve as a basis for selecting formal (i.e., complete) node dissections. To achieve this objective, studies of quantitative HFU imaging methods that go beyond conventional, qualitative, B-mode imaging are being undertaken.

Quantitative-ultrasound (QUS) imaging is being investigated by several research groups, and many tissue parameters have been estimated. This manuscript focuses on QUS methods that incorporate spectrum analysis of HFU, radio-frequency (RF) echo signals. This method is derived from the theoretical framework of ultrasound scattering established by Lizzi et al (1983) for biological tissues and subsequently expanded by him and others (Oelze et al, 2002a; Insana et al, 1990; Feleppa et al, 1986; Mamou et al, 2008; Oelze and Zachary, 2006). Frequency-dependent information derived from RF backscattered signals (Oelze et al, 2002a; Insana et al, 1990; Feleppa et al, 1986) is used to quantitatively assess tissue microstructural properties and relate them to histological properties. Therefore, our hypothesis is that QUS estimates may help to differentiate between cancer-containing (i.e., metastatic) nodes and cancer-free nodes. QUS methods are able to quantify tissue properties based on theoretical assumptions about the nature of scattering, and several groups have established QUS approaches to investigate ocular, liver, prostate, renal, and cardiac tissues at conventional frequencies (i.e., <10 MHz) for more than two decades (Perez et al, 1988; Lizzi et al, 1983, 1987; Insana et al, 1992; Feleppa et al, 2004). Our group successfully used spectrum-analysis methods at 10 MHz to show distinct differences between cancerous and cancer-free lymph nodes of breast and colorectal cancer patients over a decade ago (Feleppa et al, 1997); in those preliminary studies, a single attenuation-independent spectral parameter, spectral intercept, produced an ROC-curve area of 0.97 for identifying metastatic nodes.

More recently, interest has grown in applying QUS methods using HFU because higher frequencies allow evaluating the tissue with finer resolution than lower frequencies allow. An empirical criterion states that QUS methods are most sensitive to structures for which kD ≃ 2 (Insana et al, 1990), where k is the wave number and D is a typical size or dimension of the scattering structures. For example, operating at 25 MHz, i.e., k = 0.105 μm−1, leads to D = 19 μm in tissue. Therefore, higher frequencies allow correlating QUS estimates with tissue microstructure on a finer scale (Oelze and O'Brien, 2006; Oelze and Zachary, 2006; Mamou et al, 2005, 2008). Some fundamental high-frequency QUS studies already have been conducted on microspheres and suspended cells (Baddour et al, 2005) and cells in pellets to try to quantify apoptosis (Kolios et al, 2002). Microspheres and single-cell experiments showed agreement between experimentally- and theoretically-derived backscatter coefficients. In particular, backscatter reflection-coefficient resonances predicted by theory were observed experimentally. The results of the apoptosis study also suggested that two QUS estimates (i.e., spectral slope and midband fit) changed as a function of time in cells treated with an apoptosis-inducing drug.

Currently, lymph nodes dissected from a cancer patient either are sent to pathology for a postoperative complete histological preparation and evaluation, or they undergo an intraoperative “touch-prep” procedure (e.g., for breast cancer). The touch-prep procedure is used for sentinel nodes and is intended to detect nodal metastases immediately, i.e., while the patient remains under anesthesia in the operating room. If metastases are detected in a touch-prepped node, then a formal node dissection is performed during the same operation. In the touch-prep procedure, each dissected node is cut in half with a scalpel, and both cut surfaces are pressed on a microscope slide to transfer cells to the slide for cytological microscopic examination. Neither approach is able to detect all small metastases in lymph nodes, particularly micrometastases smaller than 2 mm. The touch-prep approach suffers from a large number of false-negative determinations because the pathologist only examines cells from two adjacent surfaces of the lymph node, and the cells derived from these surfaces may not reveal the presence of a small cancerous region within a metastatic node.

Postoperatively, all dissected nodes (including touch-prepped nodes) undergo a complete histological evaluation that involves thick sectioning into blocks (2 to 3 mm thick), fixation and embedding, thin sectioning of the surfaces of the thick sections, placement of thin sections (3 to 4 μm thick) on microscope slides, histochemical staining, and visual microscopic examination of stained thin sections. This method reliably detects nodal metastases that are present in the examined thin sections, but only a limited number (usually 2 to 3) of thin sections are obtained from the surfaces of thick sections. Because histological examination is limited to the surfaces of the thick sections and because those thick sections can be as thick as 3 mm, small metastatic foci residing between the exposed surfaces can escape detection. The entire node volume cannot be practically examined histologically. Furthermore, the postoperative histological procedure is time consuming (e.g., requiring 2 to 3 days). In the case of sentinel nodes, if positive nodes are identified postoperatively, then the patient must be rescheduled for surgery to perform a formal lymphadenectomy.

Although the QUS methods that we are investigating eventually may allow reliable detection of nodal metastases in touch-prep specimens while the patient remains under anesthesia in the operating room, our immediate objective is to develop high-frequency QUS methods capable of reliably detecting small metastases in freshly-excised nodes so that histological examination can be directed toward suspicious regions of the node and small metastases that reside between thick-section surfaces can be detected rather than being overlooked. In this paper, we focus on the methods we have developed to acquire three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound and histological data, to estimate four QUS parameters (i.e., effective scatterer size, acoustic concentration (Oelze et al, 2002a,b), slope and intercept (Lizzi et al, 1983)), and to construct color-coded QUS images. The methods and results are illustrated using 46 human lymph nodes from 27 patients with colon cancers who underwent standard surgical resection.

The present paper is organized into the following three sections: the Methods section presents our methods from surgery and lymph-node preparation to QUS image formation; the Results section presents results from the 46 lymph nodes; finally, the Discussion section presents a detailed discussion of the study to date and the next steps of the study.

The Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of the University of Hawaii and the Kuakini Medical Center (KMC) approved the participation of human subjects in the study. All participants were recruited at KMC and gave written informed consent as required by both IRBs.

METHODS

Surgery and lymph-node preparation

Lymph nodes were dissected from patients with histologically proven primary cancers (e.g., breast, colon, and gastric cancers) at the KMC in Honolulu, HI. De-identified patient information was coded and sent to Riverside Research Institute (RRI) in New York, NY. The information available for analysis at RRI was patient gender, age in years, primary cancer site, and cancer stage. Pathologists at KMC also provided RRI with a tracing of the boundary of each cancerous region in every histological section for each node.

For most cancers, a formal lymph-node dissection was performed in the established method for the specific cancer (without sentinel-node dissection and intraoperative histologic evaluation, which was used only for breast cancer). The nodes described in this paper were dissected and prepared for pathology according to the current standard of care for surgical treatment of colon cancer.

High-frequency ultrasound data acquisition

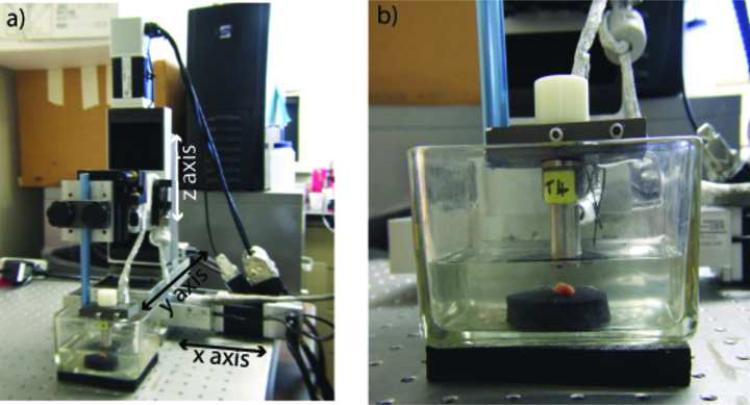

After surgical resection, dissected nodes were brought to the pathologist for gross preparation, which included isolating individual nodes and removing as much overlying fat as possible from each node. Following gross preparation, individual, manually-defatted lymph nodes were placed in a water bath containing isotonic saline (0.9% sodium chloride solution) at room temperature and scanned while pinned through a thin margin of fat to a piece of sound-absorbing material. The scanning apparatus is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

The scanning system with a lymph node pinned to a piece of sound-absorbing material. Axis orientations are shown.

Ultrasound data were acquired with a focused, single-element transducer (PI30-2-R0.50IN, Olympus NDT, Waltham, MA) with an aperture of 6.1 mm and a focal length of 12.2 mm (i.e., an F-number of 2). The transducer had a center frequency of 25.6 MHz and a minus-6-dB bandwidth that extended from 16.4 to 33.6 MHz. Figure 1a shows a photograph of our 3-axis scanning system with a lymph node being scanned. Figure 1b provides a closer view of the transducer and the lymph node pinned to the sound-absorbing material.

The transducer was excited by a Panametrics 5900 pulser/receiver unit (Olympus NDT, Waltham, MA) used with an energy setting of 4 μJ. The RF echo signals were digitized using an 8-bit Acqiris DB-105 A/D board (Acqiris, Monroe, NY) at a sampling frequency of 400 MS/s. The spacing between adjacent A-lines was 25-μm. A 3D scan of each lymph node was obtained by scanning adjacent planes every 25 μm to uniformly cover the entire lymph node. The total ultrasound scanning time was always less than 5 minutes per node, but the actual duration depended on the size of the node.

Histologic preparation

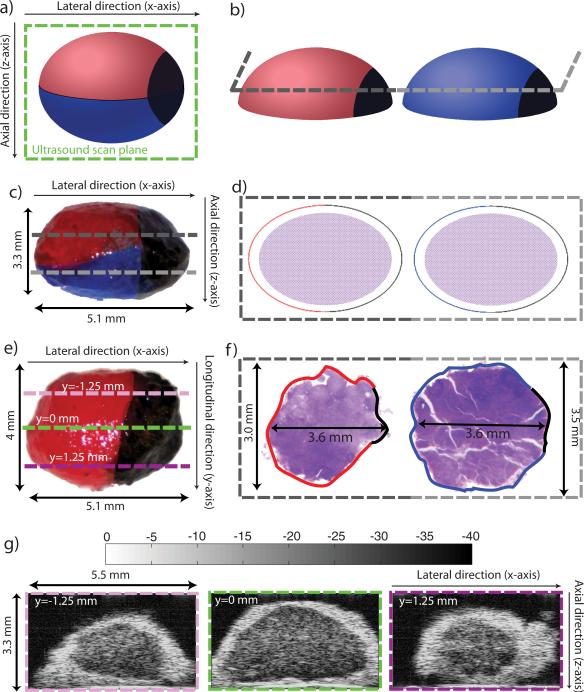

After ultrasound data collection, scanned nodes were inked to provide visual references for subsequent reassembly of histology into 3D volumes and spatial matching with volumes generated from QUS processing. Inked nodes then were prepared for histology. Figures 2a and 2c display a schematic and an actual lymph node after inking. Red and blue inks divide the surface of a whole node into two sections (i.e., to recover top and bottom) and a circle of black ink was placed at a junction between the two colored sections (i.e., to recover left and right). The complete node was photographed using a digital camera (FujiFilm FinePix S9100, Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with Hoya +2 and +4 close-up lenses (Hoya Corp., Tokyo, Japan) in order to estimate the size of the lymph node prior to histologic preparation including tissue fixation and subsequent shrinkage. In this study, we approximated each lymph node as an ellipsoid; sizing the lymph node consisted of measuring the length of the three main axes of the lymph-node-approximating ellipsoid as illustrated in Figs. 2c and 2e.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the geometry-conserving, histology, and sizing procedures of a lymph node: a) inking cartoon; b) sectioning cartoon prior to embedding for histology; c) and e) sizing photographs of a colon-cancer lymph node; d) and f) cartoon and sizing photographs of histology section; and g) three conventional B-mode images (40-dB dynamic range) obtained at different y locations (y = 0 is the central section of the lymph node). Shrinkage due to fixation is estimated from the dimensional changes in c) and e) compared to f). The scanning planes are indicated by the dashed pink, green, and purple lines in Fig. 2e. The complete 3D ultrasound data set of this lymph node contains 160 sections.

Following sizing, the node was cut longitudinally, approximately in half, perpendicular to the black-inked region at the junction between the red and blue inks, as indicated in Fig. 2a. The two half-nodes were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin with the flat cut surface oriented downward in the embedding cassette, as illustrated in Fig. 2b. During the fixation process, the fatty components of the fibro-adipose layer surrounding the lymph node were dissolved by solvents used in histological preparation, which left behind a lacy remnant consisting of connective tissue.

After fixation, the two half-nodes were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain. Figures 2d and 2f show a cartoon and an actual pair of half-node histology sections adjacent to the flat cut plane, respectively. One cut plane is shown on Figs. 2b to 2d with two different shades of gray to illustrate how 3D histologic volumes were derived from histology sections. In most histology sections, orientation was easily recovered because the blue-, red-, and black-inked boundaries were visible at the edges of the connective tissue. (In Fig. 2f, the visible blue, red, and black inks are enhanced digitally for display purposes.)

Each pair of stained thin sections was 3 μm thick and acquired every 65 or 115 μm depending on the size of the lymph node. Microscope slides containing the H&E-stained thin sections were evaluated by a board-certified pathologist. The pathologist identified and demarcated the border of each detected focus of metastatic cancer in the examined thin sections. Each slide was placed on a light box and fine-resolution bitmap images of each stained section were acquired using the same digital camera settings that were used for lymph-node sizing. (In conventional node evaluations, the pathologist characterizes each lymph node based on only 2 or 3 of the stained histology sections. However, in our study, all thin sections were histologically evaluated; this typically involved 15 to 30 thin sections per node.)

The set of bitmap images of the histologic sections was used to reconstruct a 3D histological model of the node with an inter-section spacing that matched the original separations (i.e., 65 or 115 μm) between the thin sections. The 3D histology reconstruction was intended to enable spatial matching of histologically-proven, metastatic cancer foci with their signatures in QUS images.

To explain the spatial relationships between ultrasound scan planes and histology sections, three dashed lines are included on Fig. 2e to symbolize three of the ultrasound scan planes. Their spatial locations are quantified by their y coordinate in reference to the center plane depicted by the green dashed line. The center plane is also visible in green on Fig. 2a. The ultrasound images corresponding to these three scan planes are shown in Fig. 2g. The colors used around the ultrasound images are the same as in Fig. 2e.

Thee-dimensional lymph-node and fat segmentation

A region-based, semiautomatic, 3D segmentation method was implemented in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA). First, each A-line was downsampled by a factor of 8 by using the approximation coefficients of the wavelet transform of the A-line envelope computed with Mallat's pyramidal algorithm (Mallat, 2009). (The mother and dual wavelets were the Cohen-Daubechies-Feauveau symmetric biorthogonal wavelets (Cohen et al, 1992) with 4 vanishing moments.) The resulting envelopes were log-compressed. Then, the 3D watershed transform was applied to the 3D H-minima transform (Soille, 2002) of the 3D Deriche gradient (Farnebäck and Westin, 2006) of the log-compressed approximation coefficients. The H-minima transform was used to remove local minima of the 3D gradient which limited the number of regions returned by the watershed transform.

In order to classify each watershed-deduced region as saline, tissue or fat, a pseudo-maximum-likelihood classifier was designed. The classifier used the mean intensity of each region for classification and relied on the assumption that at a given depth, a saline voxel is usually less echogenic than a tissue voxel which also is less echogenic than a residual-fat voxel. The classifier used two thresholds, T1 and T2, to classify voxels based on which of the conditional probability density functions (PDFs), p(x|C) with C being saline, tissue, or fat, was the greatest. Therefore, a region with a mean-intensity value was classified as saline if , tissue if , and fat if .

The tissue PDF was estimated from voxels located in a small 3D region centered at the transducer focus and in the middle of the xy-plane; this volume usually was right at the center of the lymph node. The saline PDF was estimated from voxels located in the top four corners of the 3D RF data set; these corners are assumed to be saline because the lymph nodes can be assumed to be ellipsoidal. Finally, the residual-fat PDF was estimated using voxels from a 3D slice of the log-compressed approximation coefficients parallel to the focal plane (i.e., z between 12.05 and 12.15 mm). Because fat voxels usually have a higher intensity than that of tissue or saline, the regions within this slice with the 10% highest mean-intensity values were selected and used to estimate the residual-fat PDF. Furthermore, to compensate for transducer diffraction, T2 was rendered depth (d) dependent: T2(d) = T2 + K(d) where K(d) is the maximum of a reference echo at depth d. Finally, residual artifacts (if any) of the 3D segmentation were corrected by an expert using custom software. A previous study showed that even without human correction, the 3D segmentation algorithm produced satisfactory results on a limited, but representative, set of lymph nodes (Coron et al, 2008).

Three-dimensional quantitative-ultrasound methods

Microstructural tissue properties were quantified using high-frequency QUS methods to test the hypothesis that QUS estimates are statistically different between cancerous (i.e., metastatic) and non-cancerous tissue in lymph nodes. Subsequent sections in this paper describe in detail the three steps we used to form QUS images that depict microstructural properties of tissue.

Three-dimensional cylindrical regions of interest

The complete 3D RF data set was separated into overlapping 3D cylindrical regions of interest (ROIs) having a diameter of 1 mm and a length (i.e., along the axis of the transducer) of 1 mm. The size of the ROI was chosen based on the resolution cell of our imaging system. Theory predicted the axial and lateral resolutions of the HFU imaging system to be 43 and 116 μm, respectively. Therefore, a cylindrical ROI contained about 1728 resolution cells, which would allow independent scattering contributions to average. The overlap between adjacent ROIs depended on the total number of voxels of the 3D RF data set; it was adjusted to permit smaller data sets to have sufficient ROIs for statistical stability and to avoid overly-long computation times for larger data sets. Table 1 shows the spacing between the different ROIs depending on the number of voxels in the data set. The spacing values quoted in Table 1 certainly result in a large correlation between adjacent QUS estimates. However, we conducted a variety of tests and found these spacings to provide a reasonable compromise between QUS image pixel size, QUS image smoothness, and computation time.

Table 1.

Spacing between adjacent ROIs depending on the total number of voxels of the 3D RF data set. Spacings are equal to the sizes of QUS voxels.

| Number of voxels (NV) | Δx (mm) | Δy (mm) | Δz (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NV > 86 × 106 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| 34 × 106 < NV ≤ 86 × 106 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| NV ≤ 34 × 106 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

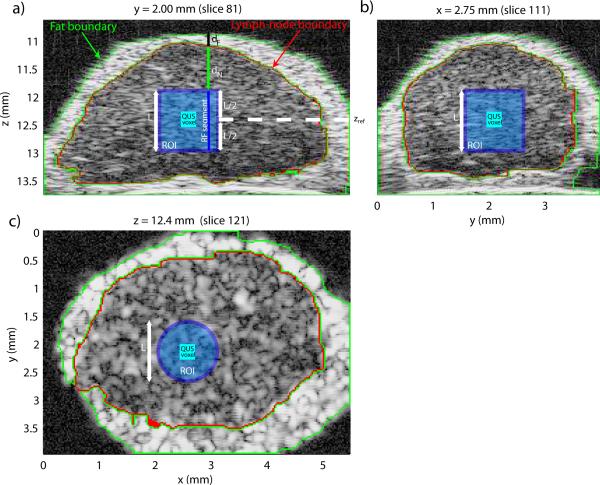

Figure 3 shows three cross sections of a segmented lymph node. The 3D segmentation results are depicted by the green and red highlights in all three cross sections. QUS estimates were computed only when the 3D ROI was entirely composed of lymph-node tissue (i.e., inside the red highlight). The light-blue square in Figs. 3a and 3b and the light-blue circle in Fig. 3c depict a 3D cylindrical ROI (L = 1 mm). QUS parameters were estimated in each ROI to generate QUS images having a voxel size corresponding to spacing between adjacent ROIs (Table 1). The dark blue square in Fig. 3 depicts a QUS voxel corresponding to the surrounding cylindrical ROI.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the QUS processing of a colon-cancer lymph node. a) Cross section at y = 2.00 mm, b) cross section at x = 2.75 mm, and c) cross section at z = 12.4 mm.

Water-oil calibration

As stated in the Introduction, QUS images depict tissue properties in a system-independent manner. To remove system dependence, a common method is to acquire the reflection of a planar reflector over a range of depths using the same instrument settings as those used during lymph-node data acquisition (Lizzi et al, 1987; Oelze et al, 2002a; Insana et al, 1990). Tissue is a weak reflector of sound because the acoustic impedance of the great majority of tissue scatterers is within a few percent of that of water (Duck, 1990; Goss et al, 1978, 1980). To maintain the same digitizer and pulser settings, calibration ideally would use a planar reflector that also is a weak reflector of sound. In this study, we used Dow Corning 710 oil (Dow Corning Corporation, Midland, MI) because it has acoustic properties close to those of water, but is more dense than water so that ultrasound from a transducer mounted above the interface can propagate through an aqueous medium to the weakly reflecting water-oil interface (Assentoft et al, 2001; Oelze et al, 2003).

Attenuation compensation

A critical part of the signal processing and the theoretical models underlying QUS is accurately compensating for attenuation (Oelze and O'Brien, 2002). In this study, attenuation compensation is particularly critical because HFU waves are attenuated more strongly than waves at more-commonly encountered lower frequencies. Attenuation compensation was performed by utilizing an attenuation-compensation function in the frequency domain. Attenuation compensation was conducted individually for every RF segment of each ROI.

Figure 3a shows the boundaries of the layer of external, node-enveloping, fatty fibro-adipose tissue (in green) and of the lymph node itself (in red). These boundaries were obtained by the segmentation algorithm summarized above. To reach the beginning of the RF segment, sound had to travel through two layers of attenuating material with different attenuation values. The first was a layer of highly-attenuating, residual, external fibro-adipose tissue (of length dF in Fig. 3a) and the second layer was an internal layer of the lymph node itself (of length dN in Fig. 3a). Note that values of dF and dN are different for each RF segment of the 3D ROI. (A speed of sound value of 1485 m/s was used for saline, lymph-node tissue, and fibro-adipose tissue.)

To compensate for the attenuation for this specific RF segment of this specific ROI, the following attenuation-compensation function was computed (Oelze and O'Brien, 2002):

| (1) |

where L is the length of the ROI in cm, and αF (f) and αN(f) are the attenuation coefficients in Np/cm at frequency f of the fat and lymph node, respectively. In this study, the value of L was kept at 0.1 cm. The frequency-dependent attenuation coefficient of fat was measured to be 0.97 dB/MHz/cm (using a spectral-difference method applied to backscattered echoes from the fat tissue of 4 lymph nodes) at 20 MHz, and the coefficient inside the lymph node was assumed to be 0.5 dB/MHz/cm which is typical of soft tissue (Goss et al, 1978, 1980). (The spectral-difference method consists of subtracting the spectra of two ROIs at different depths and estimating the attenuation as a function of frequency and distance (i.e., in dB/MHz/cm); this method is prone to large standard deviations. We are currently investigating more robust substitution methods to estimate fat and lymph-node tissue attenuation more accurately (van der Steen et al, 1991; D'Astous and Foster, 1986).)

In Eq. (1), the first term accounts for the attenuation due to the fat layer (of length dF); the second term accounts for the attenuation inside the lymph node to the beginning of the ROI (i.e., a distance of dN traveled in the lymph node); the third term accounts for the attenuation within the ROI of length L; and the fourth term accounts for the effect of using a Hanning window over the length L of the ROI. A Hanning window was used to compute the power spectrum of every RF segment.

The attenuation-compensated power spectrum of the RF segment of this specific ROI was computed by:

| (2) |

where FT is the Fourier transform operator, RFL is the raw RF-segment time-domain signal data, and HL is the Hanning window of length L centered on the middle of the RF segment.

Finally, the attenuation-compensated power spectrum of the entire ROI, SROI(f), was computed by averaging the attenuation-compensated power spectrum of each RF segment as:

| (3) |

where N is the number of RF segments within the ROI and Si(f) is the attenuation-compensated spectrum of the ith RF segment of the ROI computed using Eq. (2). In this study, N is equal to 1251 because the adjacent A-lines were 25 μm apart and therefore the radius of a cylindrical ROI was composed of 20 A-lines and π202 ≈ 1251.

Parameter estimation and QUS-image formation

Following averaging, SROI(f) was divided by the calibration spectrum of the water-oil interface located at the center depth of the ROI (i.e., zref on Fig. 3a). The resulting spectrum was log-compressed to produce the normalized power spectrum (in dB) of the ROI (Oelze et al, 2002a):

| (4) |

where

| (5) |

and RFoil(t, zref) is the RF time signal of length L obtained from the reflection of the water-oil interface at a depth zref. R(f) is the frequency-dependent pressure reflection coefficient of the water-oil interface. Numerical values of R(f) were obtained from 1 to 100 MHz by fitting reflection-coefficient measurements to a reflection-coefficient model that included an attenuating medium (i.e., the oil has a complex impedance, see Eq. (8.3.3) of (Kinsler et al, 2000)).

Estimates of four independent QUS parameters were obtained by fitting two different models to Eq. (4) over an ROI-dependent frequency band (i.e., the fitting band). The first model was a straight line and led to estimates of spectral intercept (I) and spectral slope (S). The second model was a Gaussian scattering model (i.e., a Gaussian form factor (Insana et al, 1990)); this model yielded estimates of effective scatterer sizes (D in μm) and acoustic concentration (i.e., CQ2 expressed in dB mm−3). Briefly, QROI(f) = WROI(f)−40 log(f) is fit to an affine function of f2, i.e., QROI(f) ≃ Mf2+N. Finally, D is estimated from M only and then CQ2 is estimated from D and N (Oelze et al, 2002a).

The frequency band over which the models were fit to QROI or WROI was varied between each ROI using an SNR-estimation algorithm. Theory predicts that standard deviations of QUS estimates decrease when the fitting band increases in width (Oelze et al, 2002a; Chaturvedi and Insana, 1996). Therefore, the algorithm was designed to yield wider fitting bandwidths to ROIs with a better estimated SNR. A virtual planar-reflection spectrum, , was computed following Eqs. (2) and (3) except that RFL(t)HL(t) was replaced by RFoil(t, zref) and that in Eq. (2) A(f) was replaced by (to “add” attenuation instead of compensating attenuation). Physically, can be understood as what the reflection of the water-oil interface RF spectrum would be if a water-oil interface were “embedded” inside the lymph node at the same location as the considered ROI. Then, the fitting band, , was determined by:

| (6) |

The fitting bandwidth, , was also defined by:

| (7) |

If was smaller than 10 MHz, then estimates were not computed because the ROI was considered to be too noisy. On the contrary, if was larger than 20 MHz, then was shrunk around its center frequency to reach 20 MHz. Fitting bandwidths larger than 20 MHz were judged unrealistic based on the properties of the imaging system.

Equation (6) provided a fitting band in a very different fashion than most QUS studies, which typically choose their fitting band based on the −6, −8, or −10 dB bandwidth of the spectrum of the echo from a planar reflector located at the focus of the transducer. Here, the frequency band obtained by Eq. (6) is based on an estimated noise plateau. Literally, Eq. (6) selects the frequency band 12 dB below the estimated signal strength in this ROI. Therefore, if the noise level in the system is assumed constant, then Eq. (6) can also be understood as selecting a bandwidth by a constant amount above the noise plateau.

The estimation process was repeated for all adjacent ROIs within the entire segmented lymph-node tissue. 3D QUS images were formed by color-coding and overlaying the parameter values (i.e., D, CQ2, I, or S) on the conventional B-mode volume. Also, ROIs that were not fully contained in depth between z = 10.9 mm and z = 13.3 mm were not processed because they were judged to be too far away from the nominal focal depth of the transducer.

Materials used

The results described in the next section pertain to 46 lymph nodes excised from 27 different patients diagnosed with colon cancer. These lymph nodes either were entirely negative for metastases (N = 37), or were nearly completely filled with metastases (N = 9).

RESULTS

Illustrative QUS results

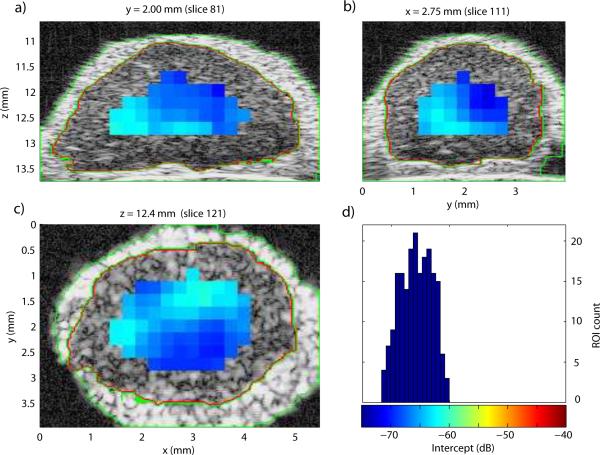

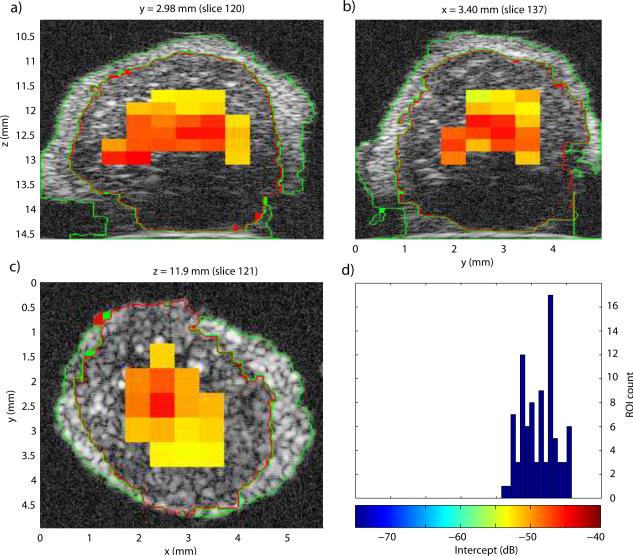

To illustrate the results of the 3D QUS processing, Fig. 4 displays the three cross sections of the lymph node shown in Fig. 3 augmented by the color-coded intercept information. A color bar and histogram of intercept distribution are shown in Fig. 4d. This illustrative node was entirely non-metastatic. Intercept values were fairly uniform centered around −66 dB. For comparison, Fig. 5 displays the intercept cross sections of an entirely metastatic lymph node from a different patient. The color scale of Figs. 4 and 5 are the same for easier comparison. For this lymph node, the intercept values were higher, centered near −48 dB.

Figure 4.

a)-c): QUS cross-section images of the intercept parameter of a non-metastatic lymph node. d) Histogram of intercept estimates.

Figure 5.

a)-c): QUS cross-section images of the intercept parameter of a completely metastatic lymph node. d) Histogram of intercept estimates.

In Figs. 4 and 5, the areas in the cross-section images devoid of estimates are due either to the fact that the ROI sizes are much greater than the QUS voxels (as illustrated in Fig. 3) or to the fact that the fitting bandwidth was smaller than 10 MHz, as in deeper regions of the lymph node shown in Fig. 5.

Figures 4 and 5 illustrate how differentiating a metastatic node from a non-metastatic node is possible. The metastatic node has higher intercept values and its QUS images are red whereas the QUS images of the non-metastatic node are blue. Also, these images indicate that the 3D segmentation is of high quality; what appears to be fat, nodal tissue and saline solution are clearly demarcated on all cross sections for both lymph nodes.

Overall, QUS cross-section images of any of the four parameters would look very similar to those shown in Figs. 4 and 5. The average estimated effective scatterer sizes are 26.4 and 36.7 μm for the non-metastatic and metastatic nodes (with standard deviations smaller than 3.0 μm), respectively. Similar contrast would also be visible in QUS cross-section images of the slope (mean slope values are 0.34 and −0.02 dB/MHz (standard deviations smaller than 0.11 dB/MHz), for the non-metastatic and metastatic nodes, respectively). The slope and size estimates are consistent with each other; they indicate that the tissue structure responsible for scattering in the metastatic node is larger than that in the non-metastatic node.

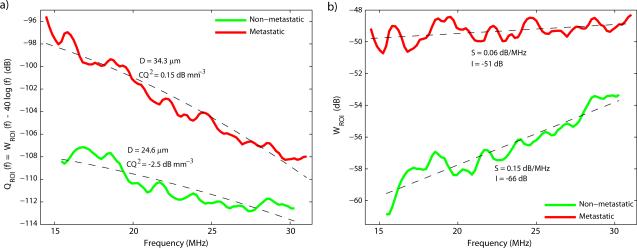

Figure 6 displays the normalized spectra and fits for a typical ROI from each of the two lymph nodes of Figs. 4 and 5 and for each scattering model over their respective fitting band. Estimate values also are indicated on the figure. The first striking feature of Fig. 6 is that for both models, the metastatic and non-metastatic lymph nodes have very different normalized spectra; a great contrast exists in overall amplitude and also in the variation with frequency. Logically, this contrast translates into differences in all QUS estimates. Figure 6 also indicates that fit quality is satisfactory for both models, and based on the figure, selecting the superior model would be difficult. Finally, Fig. 6 indicates that the fitting bands (defined by Eq. (6) for each ROI) are slightly different for these typical ROIs; the fitting bandwidth obtained from Eq. (7) for the metastatic node is slightly wider than that of the non-metastatic node.

Figure 6.

Normalized spectra, fits and estimated parameters for a typical ROI from each of the two illustrative lymph nodes of Figs. 4 and 5 using the Gaussian form factor (a) and the linear model (b).

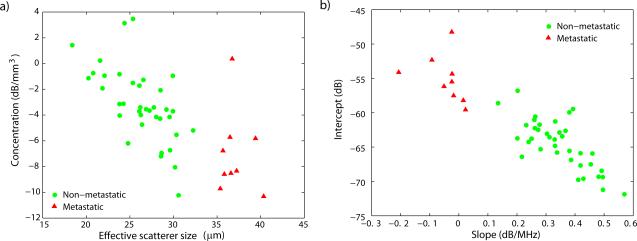

Lymph-node classification based on QUS estimates

For each lymph node, the QUS estimates were averaged for all of the ROIs in which the estimation algorithm returned a value. Then, we evaluated whether correctly classifying lymph nodes was possible based on four QUS estimates (effective scatterer size, acoustic concentration, intercept, and slope). Table 2 displays the average and standard deviations of the QUS estimates for the metastatic and non-metastatic nodes. Table 2 indicates that metastatic nodes have significantly larger effective-scatterer-size estimates (i.e., D) and higher intercept estimates (i.e., I), and significantly lower slope (i.e., S) and acoustic concentration estimates (i.e., CQ2). (The ANOVA test showed statistical differences (p < 0.05) in metastatic and non-metastatic values for all four QUS parameters.)

Table 2.

Average QUS estimates (means ± standard deviations) for the non-metastatic and metastatic nodes. (The symbol “*” indicates statistical significance based on ANOVA results giving p < 0.05.)

| Gaussian scattering model | Linear model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Node | D μm) | CQ2 (dB mm−3) | I (dB) | S (dB/MHz) |

| Non-metastatic (N=37) | 26.3 ± 3.3* | −3.18 ± 2.87* | −64.6 ± 3.6* | 0.35 ± 0.10* |

| Metastatic (N=9) | 37.1 ± 1.7* | −7.05 ± 3.21* | −55.1 ± 3.4* | −0.04 ± 0.07* |

Figure 7 displays the scatter plot of the QUS estimates obtained for the two different scattering models: the Gaussian form factor shown in Fig. 7a and the straight-line fit shown in Fig. 7b. The figure shows perfect separation between the metastatic and non-metastatic nodes for size and slope estimates and slight to moderate overlap for intercept and acoustic-concentration estimates. The software package ROCKIT (Charles Metz, University of Chicago) was used to generate an ROC curve for the intercept and acoustic-concentration estimates. Using the Gaussian form factor, metastatic nodes can be perfectly classified by setting a size threshold of 33 μm. The moderate overlap among the acoustic-concentration values produced an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.83 ± 0.09; therefore, acoustic-concentration estimates alone would classify lymph nodes only moderately well. Using the linear model, metastatic nodes can be perfectly classified by setting a slope threshold of 0.05 dB/MHz. The slight overlap among the intercept-estimate values produced an AUC of 0.98 ± 0.02; therefore, intercept estimates alone would allow near perfect classification. These results are consistent with theory that states that slope and effective scatterer size are directly related (Lizzi et al, 1997); however, the intercept parameter is not directly related to acoustic concentration because the intercept value also depends on effective scatterer size (Lizzi et al, 1997).

Figure 7.

Scatter plots of estimates by model. a) Effective scatterer size and acoustic concentration (Gaussian form factor) and b) intercept and slope (straight-line model).

In summary, Table 2 and Fig. 7 present very encouraging preliminary results. These results indicate that our QUS methods are able to classify the nodes that either are completely metastatic or are completely free of metastatic tissue. Furthermore, the results indicate that D, S, or I alone possibly could be used for satisfactory classification and detection of micrometastases. This fact could be significant in the clinic where 3D single-parameter QUS images easily can be generated. However, based on the current results, a definitive determination of which of the scattering models performs better is not possible because both provide perfect classification for this set of lymph nodes.

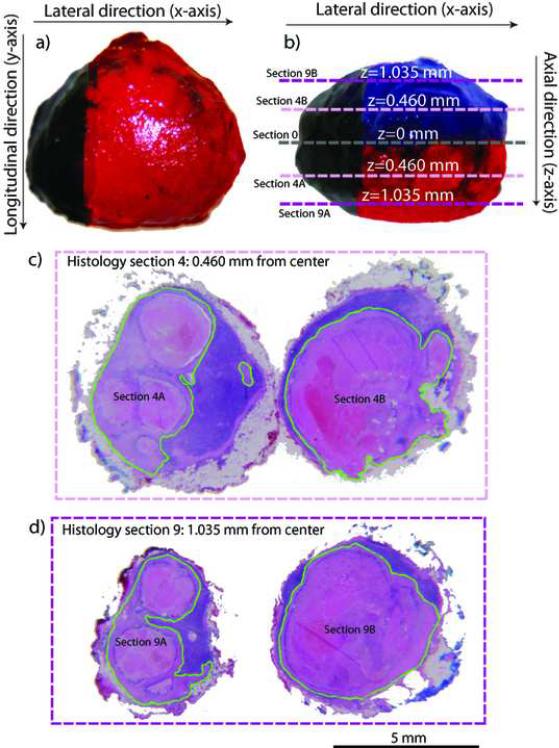

Histology and pathology assessments

When a histological section contained metastatic tissue, the pathologist digitally demarcated the boundary of the metastatic tissue using green color on the histology photomicro-graph. Figure 8 displays the sizing photomicrographs in Figs. 8a and 8b, and H&E-stained histologic-section pairs of a metastatic lymph node in Figs. 8c and 8d. The scales of all the images are the same, and a 5-mm bar is included at the bottom. Figure 8b shows the cutting planes for the two histologic-section pairs; sections 4 and 9 are illustrated. The displayed lymph node was considered to be a large node and, therefore, histology sections were acquired every 115 μm. Consequently, the two halves of section 4 (i.e., sections 4A and 4B in Figs. 8b and 8c) were 0.460 mm (i.e., 4×115 μm) from the cutting plane (i.e., section 0 in Fig. 8b). The two halves of section 9 were 1.035 mm from the central cutting plane.

Figure 8.

Lymph-node inking and H&E-stained demarcated histological sections. a) and b): sizing photographs of representative metastatic lymph node. c) and d): Sections 4 and 9 of the corresponding histology data set. Each histology section is composed of two halves, one above and one below the cutting plane.

The images of Fig. 8 demonstrate that a large part of this node is metastatic and they also indicate that the histology sections are slightly smaller than the originally dissected nodes. This apparent smaller size of the same lymph node has two origins. First, the sizing photomicrographs of freshly-dissected nodes include the residual fibro-adipose layer surrounding the nodes. The layer thickness can vary between 0 and 500 μm depending on the node and location within the node. As stated previously, histologic processing dissolves the fat from the fibro-adipose tissue layer so it is not present in the histology photomicrographs; removal of the fat from this layer results in a smaller overall size. The second reason is the inherent shrinkage of tissue by fixation during histologic preparation.

DISCUSSION

These studies were motivated by earlier studies that suggested that spectral parameters or quantitative estimates of tissue-scatterer properties derived from them could prove useful in distinguishing freshly-excised cancerous lymph nodes from cancer-free nodes of patients being treated surgically for cancer. The earlier studies conducted at lower frequencies (i.e., 10 MHz) showed that the spectral intercept produced a very high area under the ROC curve (Feleppa et al, 1997).

The present paper extends the earlier studies. It introduces a refined set of methods to investigate lymph nodes from cancer patients. The set of methods described here includes acquisition and processing of 3D HFU and histological data sets. The emphasis of the paper is on a 3D QUS imaging method that we believe can be used as a novel diagnostic tool for reliable and rapid detection of regions in dissected nodes that are suspicious for metastatic cancer and that warrant targeted evaluation by a pathologist. If successful, the method we are investigating will be faster and less likely to produce false-negative determinations than either current intraoperative touch-prep or traditional postoperative histology. The methods are presented in detail from the surgery and lymph-node preparation to the image and signal processing necessary to form QUS images. In particular, a strength of this study is that the complete chain of processing from HFU scanning to diagnosis (with QUS estimates) can be rendered automatic. Therefore, reliable evaluation of the entire lymph-node volume could be obtained in a very timely fashion, without human interaction, and at much lower cost and briefer time than would be possible using current histology procedures. The preliminary results are encouraging, and perfect classification results were obtained on a set of 46 lymph nodes dissected from 27 colon-cancer patients.

Currently, all implementation is done in MATLAB because of its convenience for research-oriented signal and image processing. The automatic steps of segmentation require between 20 and 40 minutes per node to complete. Following automatic segmentation, the extra time required to segment lymph nodes that need to be manually corrected can range from 30 minutes to about 3 hours. From our experience, most segmentations must be manually corrected, typically because the classifier fails to classify regions far from the focal plane correctly. This indicates that the variation of the PDFs as a function of depth must be more carefully analyzed. The results from the manually-corrected segmented data will be used to improve estimation of PDFs.

After the segmentation, processing the 3D RF data to obtain all four QUS estimates in 3D requires less than 30 minutes even for the largest nodes. The processing time does not increase significantly for larger lymph nodes because of the reduced overlap between adjacent ROIs (as illustrated in Table 1). Consequently, generating 3D QUS images is far from real-time. However, processing time can be drastically reduced by optimizing our programs and compiling them as executable applications using a language such as C++ or Fortran. Additional reductions in processing time may be possible by using only a single estimate if classification remains reliable based on a single parameter. Furthermore, if this approach proves to be clinically effective (i.e., if we reliably can detect micrometastases in lymph nodes), then we only need to be as fast as an intraoperative touch-prep examination, i.e., we need to be able to generate QUS images in the time allowed for a patient to be maintained under anesthesia for a touch-prep evaluation. High processing speed would not be needed for nodes undergoing standard, postoperative, histological examination.

We currently are investigating the best possible approaches to spatially matching 3D histology, 3D B-mode ultrasound, and 3D QUS images. Again, we intend to be certain that QUS estimates track histological properties used for tissue typing and metastasis detection (i.e., matching green-demarcated regions on Figs. 8c and 8d with corresponding QUS estimates). Even with our careful inking and sectioning during the histology process, 3D spatial matching remains a critical and non-trivial task. Furthermore, in this project, we would like to develop and implement a completely automatic technique to match 3D ultrasound and 3D histology because we receive new data on a daily basis. To date, we have data from over 190 patients with over 600 nodes to process. Histology slides can contain an abundance of various artifacts such as tearing, shrinkage, etc.; compensation is required for such artifacts. Most of these artifacts tend to be present in sections obtained near the cutting planes. For example, in many nodes, sections 0A and 0B, which should be virtually identical to each other (because they are the closest to the common “cutting-in-half” plane), actually look markedly different because one of the sections is missing some tissue. Even if we had a nearly perfect 3D histologic data set, several other potential problems are possible. For example, the shape of the node in the ultrasound image is not literally spherical (or ellipsoidal); this anomaly can be explained by the fact that nodes tend to be more “kidney bean” shaped, and the natural node shape is sometimes altered by the pins used to fix the node in position during ultrasound scanning.

The 3D QUS methods presented here were successful in classifying a limited number of lymph nodes as either completely metastatic or non-metastatic. Therefore, in the future, we will concentrate on increasing the number of uniform lymph nodes being processed. This will strengthen our classification method and increase the confidence in them. We also have begun additional studies of lymph nodes with small micrometastatic areas that do not fill the node. For this type of micrometastatic node, QUS estimates will be tested to determine whether we can distinguish micrometastatic cancerous regions from non-cancerous regions. To detect micrometastases (i.e., < 2 mm in diameter), we may need to decrease the size of the ROIs to improve QUS-image spatial resolution. Similarly, the overlap between adjacent ROIs might be reduced to obtain more-independent estimates from one ROI to the next. Decreasing ROI size and overlap would increase responsiveness to spatial changes in tissue microstructure, e.g., changes occurring at the boundaries of micrometastases. However, this improvement in spatial resolution would come at the cost of an increased QUS-estimate variance (because each ROI would contain fewer independent resolution cells), which could also make the boundaries between metastatic and non-metastatic regions less distinct. A trade-off exists between QUS spatial resolution and estimate variance. Therefore, further investigation is needed to determine the optimal ROI size and overlap for satisfactorily detecting micrometastases. Another approach would be to use an ultrasound transducer with a higher center frequency, which would provide a greater number of resolution cells within an ROI of the same size; however, the trade-off would be decreased penetration depth of the higher-frequency ultrasound and therefore a reduced ability to obtain QUS estimates deep into the lymph nodes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

NIH Grant CA100183 supported these studies in part. The authors thank Drs. William D. O'Brien, Jr. and Michael L. Oelze for suggesting the use of the Dow Corning oil for calibration and for providing frequency-dependent reflection-coefficient measurements for the water-oil interface. We also acknowledge the theoretical framework for QUS developed by the late Dr. Frederic L. Lizzi in the 1980s.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aristizábal O, Christopher DA, Foster FS, Turnbull DH. 40-MHz echocardiography scanner for cardiovascular assessment of mouse embryos. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 1998;24(9):1407–1417. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(98)00132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assentoft JE, Gregersenb H, O'Brien WD., Jr. Propagation speed of sound assessment in the layers of the guinea-pig esophagus in vitro by means of acoustic microscopy. Ultrasonics. 2001;39:263–268. doi: 10.1016/s0041-624x(01)00053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddour RE, Sherar MD, Hunt JW, Czarnota GJ, Kolios MC. High-frequency ultrasound scattering from microspheres and single cells. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;117:934–943. doi: 10.1121/1.1830668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi P, Insana MF. Error bounds on ultrasonic scatterer size estimates. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1996;54:392–399. doi: 10.1121/1.415958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A, Daubechies I, Feauveau JC. Biorthogonal bases of compactly supported wavelets. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 1992;45(5):485–560. [Google Scholar]

- Coron A, Mamou J, Hata M, Machi J, Yanagihara E, Laugier P, Feleppa EJ. Three-dimensional segmentation of high-frequency ultrasound echo signals from dissected lymph nodes. Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium.2008. pp. 1370–1373. [Google Scholar]

- D'Astous FT, Foster FS. Frequency dependence of ultrasound attenuation and backscatter in breast tissue. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1986;12(10):795–808. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(86)90077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Korte CL, van der Steen AFW, Céspedes EI, Pasterkamp G, Carlier SG, Mastik F, Schoneveld AH, Serruys PW, Bom N. Characterization of plaque components and vulnerability with intravascular ultrasound elastography. Phys. Med. Biol. 2000;45(6):1465–1475. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/6/305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duck FA. A Comprehensive Reference Book. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1990. Physical Properties of Tissue. [Google Scholar]

- Farnebäck G, Westin CF. Improving Deriche-style recursive Gaussian filters. J. Math. Imaging and Vis. 2006;26:293–299. [Google Scholar]

- Feleppa EJ, Lizzi FL, Coleman DJ, Yaremko MM. Diagnostics spectrum analysis in ophthalmology: a physical perspective. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 1986;12:623–631. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(86)90183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feleppa EJ, Machi J, Noritomi T, Tateishi T, Oishi R, Yanagihara E, Jucha J. Differentiation of metastatic from benign lymph nodes by spectrum analysis in vitro. Proceedings of the 1997 IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium.1997. pp. 1137–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Feleppa EJ, Porter CR, Ketterling JA, Lee P, Dasgupta S, Urban S, Kalisz A. Recent developments in tissue-type imaging (TTI) for planning and monitoring treatment of prostate cancer. Ultrason Imaging. 2004;26:163–172. doi: 10.1177/016173460402600303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss SA, Johnston RL, Dunn F. Comprehensive compilation of empirical ultrasonic properties of mammalian tissues. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1978;64:423–457. doi: 10.1121/1.382016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss SA, Johnston RL, Dunn F. Compilation of empirical ultrasonic properties of mammalian tissues II. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1980;68:93–108. doi: 10.1121/1.384509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YP, Zheng YP, Leung SF, Choi AP. High frequency ultrasound assessment of skin fibrosis: clinical results. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2007;33:1191–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insana MF, Wagner RF, Brown DG, Hall TJ. Describing small-scale structure in random media using pulse-echo ultrasound. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1990;87:179–192. doi: 10.1121/1.399283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insana MF, Wood JG, Hall TJ. Identifying acoustic scattering sources in normal renal parenchyma in vivo by varying arterial and ureteral pressures. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 1992;18:587–599. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(92)90073-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsler LE, Frey AR, Coppens AB, Senders JV. Fundamental of acoustics. fourth edition John Wiley and Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kolios MC, Czarnota GJ, Lee M, Hunt JW, Sherar MD. Ultrasonic spectral parameter characterization of apoptosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;28:589–597. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizzi FL, Astor M, liu T, Deng CX, Coleman DJ, Silverman RH. Ultrasonic spectrum analysis for tissue assays and therapy evaluation. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 1997;8:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lizzi FL, Greenebaum M, Feleppa EJ, Elbaum M, Coleman DJ. Theoretical framework for spectrum analysis in ultrasonic tissue characterization. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1983 April;73:1366–1373. doi: 10.1121/1.389241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizzi FL, Ostromogilsky M, Feleppa EJ, Rorke MC, Yaremko MM. Relationship of ultrasonic spectral parameters to features of tissue microstructure. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 1987 May;34:319–329. doi: 10.1109/t-uffc.1987.26950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallat S. A Wavelet Tour of Signal Processing — The sparse way. 3rd Edition Academic Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mamou J, Oelze ML, O'Brien WD, Jr., Zachary JF. Identifying ultrasonic scattering sites from three-dimensional impedance maps. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2005;117:413–423. doi: 10.1121/1.1810191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamou J, Oelze ML, O'Brien WD, Jr., Zachary JF. Extended three-dimensional impedance map methods for identifying ultrasonic scattering sites. J Acoust Soc Am. 2008;123:1195–1208. doi: 10.1121/1.2822658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelze ML, Miller RJ, Blue JP, Jr., Zachary JF, O'Brien WD., Jr. Impedance measurements of ex vivo rat lung at different volumes of inflation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2003;114:3384–3393. doi: 10.1121/1.1624069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelze ML, O'Brien WD., Jr. Frequency-dependent attenuation-compensation functions for ultrasonic signals backscattered from random media. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2002;111:2308–2319. doi: 10.1121/1.1452743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelze ML, O'Brien WD., Jr. Application of three scattering models to characterization of solid tumors in mice. Ultrason Imaging. 2006;28:83–96. doi: 10.1177/016173460602800202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelze ML, Zachary JF. Examination of cancer in mouse models using high-frequency quantitative ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:1639–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelze ML, Zachary JF, O'Brien WD., Jr. Characterization of tissue microstructure using ultrasonic backscatter: Theory and technique for optimization using a Gaussian form factor. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2002a;112:1202–1211. doi: 10.1121/1.1501278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelze ML, Zachary JF, O'Brien WD., Jr. Parametric imaging of rat mammary tumors in vivo for the purposes of tissue characterization. J. Ultrasound Med. 2002b;21:1201–1210. doi: 10.7863/jum.2002.21.11.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez JE, Barzilai B, Wickline SA, Vered Z, Sobel BE, Miller JG. Quantitative characterization of myocardium with ultrasonic imaging. J. Nucl. Med. Allied Sci. 1988;32:149–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijo Y, Tanaka A, Owada N, Akino Y, Nitta S. Tissue velocity imaging of coronary artery by rotating-type intravascular ultrasound. Ultrasonics. 2004;42:753–757. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2003.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman RH, Ketterling JA, Mamou J, Coleman DJ. Improved high-resolution ultrasonic imaging of the eye. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:94–97. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman RH, Rondeau MJ, Lizzi FL, Coleman DJ. Three-dimensional high-frequency ultrasonic parameter imaging of anterior segment pathology. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(5):837–843. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30948-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soille P. Morphological Image Analysis — Principles with applications. 2nd Edition Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull DH. Ultrasound backscatter microscopy of mouse embryos. Methods Mol. Biol. 2000;135:235–243. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-685-1:235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull DH, Foster FS. Ultrasound biomicroscopy in developmental biology. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20:S29–S33. [Google Scholar]

- van der Steen AF, Cuypers MH, Thijssen JM, de Wilde PC. Influence of histochemical preparation on acoustic parameters of liver tissue: a 5-mhz study. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1991;17(9):879–891. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(91)90083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt M, Ermert H. In vivo ultrasound biomicroscopy of skin: spectral system characteristics and inverse filtering optimization. IEEE Trans. Ulatrson. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2007;54:1551–1559. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2007.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]